Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

C is for Cine-discoveries

Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers!

DB here:

Kristin and I think of Brussels as a gray city—gray skies, gray pavements, gray buildings, even gray, if often fashionable, clothes. It isn’t usually a fair description, though. In the twenty-plus summers we have been visiting, many days have been bright. I suppose our impression comes chiefly from one rainy fall we spent here in 1984, on a Fulbright research grant. Still, the public monuments bear us out, especially the Palais de Justice: except for its gold dome, it is gray, and has been encased in gray scaffolding for as long as we can remember.

Indeed, Brusselians assure us that the scaffolding will never go away because it’s holding the Palais up.

The gray motif continues this summer; during my visit, there have been almost no sunny days, just rain and chill. To prove that Belgians have stayed loyal to their favorite color, I took a shot of a new piece of public architecture near the Central Station: a half-circle of tipped-over pyramids that are, ineluctably, gray.

Still, the movies provide my light and color. I talked about Brussels as one of the great film cities in last year’s entry. I found further proof in a 2003 Marc Crunelle’s Histoire des cinemas bruxellois (in a series announced here), a small book with some fine pictures, one of which you will find at the end of this entry.

As usual, my host was the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. The archive offices remain in their splendid old building, the Hotel Ravenstein, but the new museum complex is still under construction. So the screenings continue to be held in the ex-Shell building, a piece of postwar Europopuluxe that I seem to enjoy more than most of the locals.

During my days, I watch films (very, very slowly) in the archive vaults; more about that project in my next entry. At night the event was Cinédécouvertes, the annual festival of new films that don’t yet have Belgian distribution. That festival, going back decades, has now been attached to a bigger event, the Brussels European Film Festival, which this year began on 28 June. BEFF showed thirty new titles, plus eight older items in open-air screenings, and it gave several prizes.

Kristin and I were in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato and so I missed all of these, including the big Flemish film of 2007, Ben X. But Cinédécouvertes, running on during the BEFF, had its second and final week while I was in town. Films screened were competing for a 10,000-euro prize to be awarded to a distributor that would pick up the film. In addition, the venerable L’Age d’or prize would be awarded to a film that maintained the spirit of Buñuel’s scandalous masterpiece.

Herewith some notes on what I saw, and the prize results. Of course on the day I posted this, the sun came out.

Women, prep school, and manga

Cargo 200.

The two Iranian films in the program were earnest but varying in quality. Unfinished Stories (Pourya Azabayjani) is a network narrative following three women across a single night. A suicidal teenager doesn’t return home; her path crosses with that of a wife cast out by her husband; and she in turn brushes past a young woman who tries to smuggle her newborn baby out of the hospital. The situations are engagingly melodramatic, but the links among them (a footloose soldier, a compassionate taxi driver, an enigmatic old man) seemed to me forced, and as is often the case in these tales, the problem is how to conclude each story line in a satisfying way. The use of sound was very fresh, however. I especially liked the teenager’s obsessive replaying of taped conversations with her boyfriend. Often these “auditory flashbacks” are played over a black screen, and they come to exist as discrete, almost virtual scenes.

I like it when a film begins with a sharp, defining gesture, and Three Women (Manijeh Hekmat) had one. In close-up a car drives up to a tollbooth and the driver’s hand tosses a cellphone into a Charity Box there. Someone is on the run and cutting ties, but we won’t find out more for some time.

The first stretch of the movie concentrates on Minoo, a divorced professor and expert in Persian textiles. A rug dealer has promised to keep a precious carpet in the care of her museum, but he changes his mind and tries to sell it. In a fit of temper she grabs the carpet from its owner and takes it to her car, where her somewhat senile mother waits patiently for a trip to the hospital. Then the old lady vanishes. The emphasis shifts to Minoo’s daughter Pegah, who has set out on her own. The maddening Tehran traffic of the early scenes gives way to the empty quiet of the countryside. In the second half of the film, a favorite theme of Iranian cinema—the urban intellectual confronting rural life—is played out vividly when village elders debate whether to stone a woman who has had an abortion.

Like many of the best Iranian films, Three Women tells its story with dramatic force, offering robust conflicts and a degree of suspense rare in arthouse fare. Manijeh Hekmat, who made her name with Women’s Prison, manages the story threads skilfully, creating a continuous revelation of backstory and hints about how the tale will develop. I especially liked the way Minoo gradually realizes that she has had no idea how her daughter is living. As Alissa Simon points out in her perceptive review, Hekmat can spare time for a subtle composition as well. The ending came as a quiet surprise, deflating some dramatic issues but emphasizing the comparative unimportance of carpets, cellphones, and pop music in the face of the deeper problems facing Iranian women.

Add another woman and you have Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Four Women. The quartet of stories, all adapted from literature and evidently set in the 1940s and 1950s, shows the fates befalling women in different roles, each identified with a title: The Prostitute, the Virgin, the Housewife, and the Spinster. Not much fun to serve in any of them, it turns out. The film has a sharp eye for details of local life and ceremonies, an ambition helped by the high-definition format: a slow-moving river is off-puttingly scummy. A little didactic and schematic, but it’s enlivened by a long sequence of a husband who methodically and endlessly eats everything put in front of him, with a seriousness he cannot bring to his marriage. The sequence starts in bemusement, moves to humor, and persists to the threshold of nausea.

The Argentine La sangre brota (Pablo Fendrik) was a little reminiscent of City of God in its relentless handheld assault on your senses, with the camera grazing faces and people racing in pursuit of drugs and money, with a beleagured taxi driver trying to do the right thing. La maison jaune (Amor Hakkar), from Algeria, appealed more to me. How much we owe neorealism! Quietly and simply, Hakkar tells of a father learning of his son’s death, fetching the body home for burial, and then trying to find a way to relieve his wife’s grief. So he paints his house yellow. Quiet and moving and not as simple, in story or pictorial technique, as it might sound.

Antonio Campos’ Afterschool (US) is a very assured first feature about drug-overdose deaths in a prep school. The story is told almost completely through the consciousness of Rob, an introspective and awkward freshman who indulges in internet porn. Passive to the point of inertia, Rob remains largely a mystery. This effect is often due to Campos’ bold use of the 2.40 widescreen frame, which often excludes some of the most important dramatic information. People are split by the left or right edge, or are decapitated by the top frameline, so we must strain to listen to the conversation and catch glimpses of the characters. This may sound arbitrary, but Campos finds ways to motivate the lopped-off compositions. One shot, when the parents of dead students record their thoughts on video, is one of the strongest pieces of staging I’ve seen this year. Unlikely to get U. S. theatrical release, if only because of its pacing, Afterschool marks Campos as definitely a director to watch. It won one of the two top Cinédécouvertes prizes.

The other top prizewinner was Yoshida Daihachi’s Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers! It’s another insane Japanese family movie—that is, the family is insane, and the movie acts the same way, out of sympathy or contagion. After the parents are killed trying to save a cat from an oncoming truck (nice overhead shot of bloody skid marks), a new household takes shape. There’s the phlegmatic brother Shinji, his maniacally cheerful wife, his adolescent sister Kyomi, and his sister Sumika, who comes to stay after failing to make it in Tokyo as an actress. Family secrets emerge. Sumika starts turning tricks and Kyomi draws violent manga inspired by Sumika’s adventures. The comedy turns blacker when Kyomi’s comic books become best-sellers and all the family problems regale the reading public. With some scenes shot in high-contrast video, as if they were TV episodes, and a climax that blends film and manga, panel by panel, the film’s style is as all over the map as the characters and their complexes. Good dirty fun from the title onward.

The L’Age d’or prize went, deservedly, to Cargo 200 from Russia. Another black comedy, but one that gets blacker and less funny as it goes along, it becomes sort of a post-Glasnost’ Last House on the Left. (Seriously, maybe there’s an influence of Saw and Hostel here, with hints of Faulkner’s Sanctuary.) Set in 1984 and stuffed with retro clothes, hairstyles, and music, the plot spins crazy-eights around the corpse of a returning Afghan war hero; a teenager trying to buy homebrew vodka; a bootlegger who keeps a Vietnamese refugee as an assistant; a small-town policeman with a penchant for voyeuristic sex; and a professor of dialectical materialism who wanders, blinking, in and out of the lurid plot twists. Director Alexei Balabanov, who did the pioneering rough genre picture Brother (1997), gives no quarter here.

Strength in simplicity

Albert Serra directs the three kings in El cant dels ocells.

My three favorites were all resolutely unfancy. Shultes, a Russian item by Bakur Bakuradze, is a minimalist study of a pickpocket. Shultes lives with his mother, gives some of his loot to his legit brother, and takes up with a boy whom he tutors in thievery. At slightly over 200 shots, the movie is staged, shot, and cut with a precision that reminded me of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Syndromes and a Century). On the inexpressiveness scale, Shultes, with eyes and mouth too small to fill up much of his face, makes Bresson’s pickpocket look positively other-directed.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

Shinji Aoyama is best known for Eureka (2000), which won a prize at an earlier Cinédécouvertes. Sad Vacation is one of those films that try to do justice to the ways in which humans become tangled in relationships based on acquaintance, momentary bits of kindness, and sheer chance. Kenji helps smuggle Chinese workers into Japan, but when one dies, Kenji takes the orphan boy under his wing. Soon characters and connections proliferate. There is the salariman and his dumb pal searching for the runaway Kozue. Kenji cares for a slightly daft girl, and he becomes romantically involved with the bargirl Saeko. Accidentally he finds the mother who deserted him, and he joins her new family, complete with mild-mannered father and rebellious brother. Always hovering around are several men and women who work for the father’s trucking company—people rescued, it’s implied, from crime or neglect.

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Some films, like those of Angelopoulos, seem to spit in the face of video. You can’t say you’ve seen them if you haven’t seen them on the big screen. Such was the case with my favorite of the films, The Song of the Birds (El cant dels ocells, 2008) by the Catalan director Albert Serra. It merges an aesthetic out of Straub/ Huillet—black and white, very long static takes, drifts and wisps of action—with a joyous naivete recalling Rossellini’s Little Flowers of St. Francis. Serra’s film also reminded me of Alain Cuny’s L’Annonce fait à Marie (1991) and one of the greatest of biblical films, From the Manger to the Cross (1912). All make modest simplicity their supreme concern.

We three kings of Orient are . . . well, definitely not riding on camels. We are in fact trudging through all kinds of terrain, scrub forests and watery plains and endless desert, to visit the baby Jesus. We are also quarreling about what direction to go, whether to turn back, and why we have to sleep side by side so tightly that our arms go numb. And in an eight-minute take we are struggling up a sand dune, vanishing down the other side, and then staggering up again in the distance.

The three kings aren’t characterized, and they are sometimes unidentifiable in the long-shot framings; only their body contours help pick them out. Intercut with their non-misadventures are glimpses of an angel (whom they may not see) and stretches featuring Joseph and Mary, who caress a lamb. Eventually the infant Himself puts in an appearance, burbling. When the kings finally arrive, one prostrates himself. The image settles into a tidy, unpretentious classical composition and we hear the film’s first burst of music, Pablo Casals’ cello rendering of the folk tune Song of the Birds.

The kings get a chance to bathe in a scummy pool before returning home. Off they trudge. “We’re like slaves!” one complains. In a final shot that would be sheer murk on a DVD, they swap robes and set off in different directions. Did I see them embrace one another? Did they murmur something? I couldn’t tell for sure. Night was falling and they were far away.

Like Casals’ cantata El Pessebre, The Song of the Birds gives us a Catalan nativity. The simplicity is genuine, not faux-naif, and the humility doesn’t preclude humor. Although the shots are quite complex, the spare surface texture invests a familiar story with a plain, shining dignity. Discovering films like this, which you will never see in a theatre and could not bear to watch on video, makes this ambitious festival such a worthy event. It maintains the heritage of one of the world’s great cinema cities.

Next up: A report on films I’m watching at the archive’s vaults on–no kidding–the Rue Gray.

The Metropole, Brussels, 1932.

Thanks to Jean-Paul Dorchain of the Archive for help in finding illustrations. And apologies to readers who came here and found only a stub earlier. An internet gremlin somehow purged the first version of this entry a few hours after it was posted.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

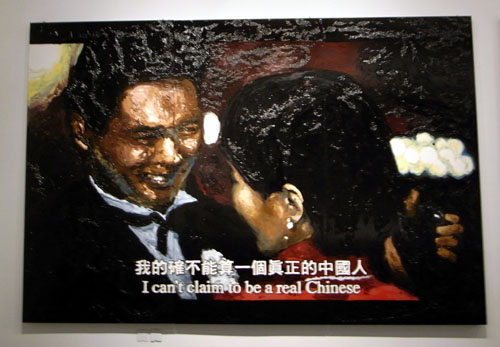

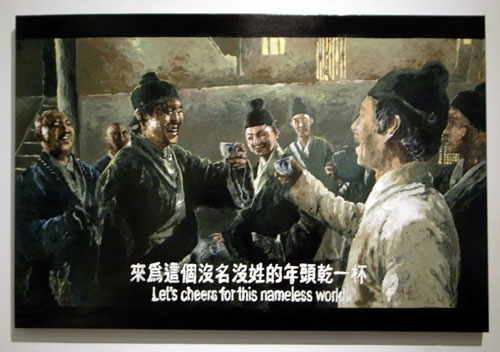

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

Japan journey, part 2

DB here:

A seesaw trip in my last few days in Japan, with notes on watching some rare movies, visiting some superheroes, and watching some children cut down swaggering samurai.

Kansai wanderer

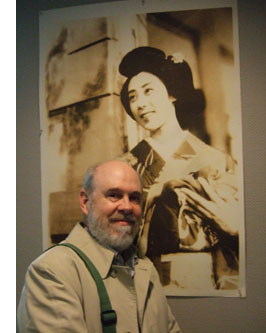

On Friday I traveled to Nagoya University with Yamanouchi Etsuko. She was my translator for a talk on Japanese film for my student, now professor, Fujiki Hideaki (above). Hideaki oversaw the translation of Film Art into Japanese and is the author of a new book on the growth of movie culture in Japan during the first decades of the century.

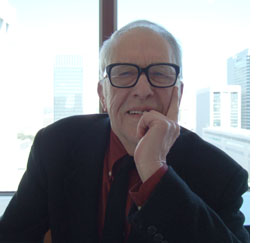

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

Because I lectured on what I call the “game of vision” in Japanese films, we had fun at dinner with composing shots that mimicked the peekaboo framings. Even relaxing, film wonks never turn off the movies running in our heads.

Next day I took a fairly impulsive trip to Kyoto. I tried to visit Mizoguchi’s grave, but had no luck finding it. After visiting it ten years ago, I shouldn’t have trusted my memory. Instead, I found Toei’s movie theme park, which provided me three hours of diversion.

Shochiku studios failed with its own theme park (go here for my reminiscence of it), partly because it had only Ozu and Tora-san as main attractions. But Toei has a bevy of swordplay heroes and….Power Rangers. An entire wing of the facility is dedicated to superheroes, life-size and some much larger.

I had no idea who these hardfaced bipeds were, but they sure looked pretty, with their nice snowmobiles and vaguely obscene gestures.

Elsewhere in the Toei park are streets evoking old Edo and Kyoto, as well as a kabuki theatre.

Mechanical ninja crawl around overhead, and samurai stroll the alleyways. You can watch a director pretending to shoot a TV show of swordplay in a studio set.

The most enjoyable moments came with a display of swordfight stunts carried out by three good-humored young samurai. They summoned from the audience a tiny boy, a somewhat older boy, and a tall little girl, and they gave them some elementary fighting skills. These skills consisted of stomping forward, crouching, and swinging the sword while letting out a blood-freezing shriek. The teachers made it look easy.

Then each kid was planted in front of the crowd and a swordsman rushed forward, with howling abandon. Miraculously, the kids’ fairly minimal defense tactics always defeated the men, who died in agony.

When one winner got obeisance from his enemies, he acted like the constantly scratching Mifune in Seven Samurai.

A new old Mizoguchi

Back to Tokyo and a round of shopping, eating, and moviegoing. I was staying with Komatsu Hiroshi, a friend of almost thirty years whom I first met at a conference on Dreyer in Verona. Hiroshi is a monumental figure in silent-cinema circles, and I’m planning a later blog entry profiling him.

With Hiroshi I saw two silent Makino Masahiro films at the national Film Center. For more on this series, see an earlier entry. Chronicle of 3 Generations (Gakkusei san daki, 1930) consisted of two installments of a short-comedy series produced by Makino. In the first, a modern girl throws over her boyfriend because he’s a bad baseball player. The second was reminiscent of Ozu’s Days of Youth in showing a college student trying to hide his slacker ways from his visiting father.

The second film, also part of a series, was directed by Makino. Street of Ronin (Roningai, 1929) was a bustling tale of a neighborhood of ne’er do wells. The benshi commentator must have been busy; there are over 260 intertitles in a film of about 72 minutes. I can’t tell you what happened in the plot, but the movie shows yet again that by the end of the 1920s Hollywood continuity style was in full vigor here. Makino uses a remarkable number of different setups in each scene.

At Hiroshi’s house he screened many rare items from his collection, mostly silent European, American, and Japanese films. One of the most striking Japanese titles was Magic in the Dark (Kurayami no Tejina, 1927), an experimental short with some of the stylization one finds in Kinugasa Teisuke’s Page of Madness (1926). The rain-drenched night scenes are like something out of Murnau.

The plot is didactic and uplifting, showing how a boy tempted by money pursues a righteous path. Magic in the Dark was directed by Suzuki Shigeoshi, whose most famous film is What Made Her Do It? (1930). That famous but currently incomplete feature, along with Magic in the Dark, will be released on the Kinokinuya DVD series that Hiroshi directs. Alas, no English subtitles. (See the PS below.)

The killer item was a newly discovered Mizoguchi film, one that doesn’t appear on official filmographies! Miss Okichi (Ojo Okichi, 1935) was residing in the Shochiku vaults, and a copy, in beautiful condition, was recently screened on Japanese television. Mizo codirected it with Takashima Tatsunosuke, a director whose work I don’t know, for Dai Ichi Eiga, the production company he formed with Nagata Masaichi. Dai Ichi Eiga, which later became Daiei, financed Mizo’s masterpieces Naniwa Elegy (1936) and Sisters of Gion (1936).

A bit like The Downfall of Osen (Orizuru Osen, 1935), this film centers on a woman who’s a cat’s paw for a gang involved in shady dealings. Okichi, played by Yamada Isuzu (whose bosom I nestle against in my earlier entry), is pulling scams for the sake of her lover. But she falls out with the gang and takes pity on one of the young men whom she victimizes.

I can’t comment on the film after only one viewing, and the fact that Mizoguchi is credited after Takashima suggests that he may have had little input. Still, it’s another tale of a woman who sacrifices herself for more or less unworthy men. Miss Okichi also has some typically Mizoguchian scenes that dwell on chiaroscuro melancholy. Much of the film takes place at night, and this strategy reinforces the somber atmosphere. There are some remarkably opaque long shots and one moment that includes Okichi turning toward the camera in a sort of plaintive challenge.

Given my admiration for Mizo, this capped a terrific ten days in Japan. Now on to Hong Kong, where I’ll blog at intervals on what happens at the Hong Kong Filmart market, the Asian Film Awards on Monday night, and the HK International Film Festival. I’ll be there, like Bernstein in Citizen Kane, before the beginning and after the end.

PS 24 July 2008: The Kinokuniya DVD of What Made Her Do It? has come out, and Joanne Bernardi reports that at least one version does have English subtitles…by her! Magic in the Dark is included on that disc. And despite information to the contrary, the DVD Joanne has is not Region 2 but all-region. Oddly, online listings of the DVD make no mention of these facts. Joanne does not yet know whether the subtitled all-region disc is the same as the one offered on amazon.jp and the Kinokuniya site, but it seems likely. More information as I get it, from Joanne or others.

Tokyo choruses

DB here:

I’ve had a terrific time since I arrived late last Saturday. The only thing that could have improved it would be the discovery that there was a Japanese town named Bordwell. If it could happen to Barack, why not me?

Actually, I know why not. On Sunday, a trip to a temple yielded a promise that nothing good would come on any front.

Pretty dire. Yet I press on, foolishly trusting that meals will be tasty, the city will shake me up, and three fine sorts of things will grace the first phase of my stay: the symposium, the movies, and my companions. Still, I vow to avoid thinking up something bad while drinking.

The conference

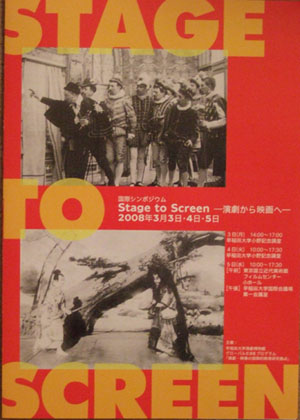

I came for a symposium at Waseda University, Stage to Screen. For three days local scholars delivered papers and comments about how cinema related to theatre.

Young researchers have done thorough work on the relation of Japanese cinema to the culture’s lively theatrical traditions. Usai Michika explored a topic that’s always fascinating–the benshi, the person who accompanied silent film with commentary and dialogue. She found a remarkable poster from the Waseda Theatre Museum collection illustrating many short films, and through diligent archive work she was able to identify most of the films. Although the poster came from 1899, the films were all pre-1896. Ogawa Sawako gave a thorough examination of how films were influenced by kodan, a sort of novelistic oral recitation. It turns out that kodan stories were at least as important as kabuki plays as sources of Japanese film, well into the 1920s. Shimura Miyoko studied later forms of rensa-geki, the mix of live performance and film that was fairly common in the silent era. She showed that there was a resurgence of it in the early 1930s, with sound cinema.

Western cinema attracted attention as well. Kataoka Noburo analyzed the relationship between Samuel Beckett’s Play and his Film, directed by Alan Schneider and starring Buster Keaton. Our host Professor Komatsu Hiroshi gave a talk called “Actors without Bodies,” suggesting the quasi-supernatural qualities of early film. He surveyed cinema’s links to the phantasmagoria shows of the French magician Robertson. He also explored how sound recordings synchronized with early films evoked theatre but didn’t exactly correspond to stage performance techniques–another form of bodiless acting.

There were two keynote addresses as well, one from Yuri Tsivian and one from me. Yuri was, as usual, energetic and infectious. Our talks naturally overlapped when we touched on the 1910s, and we had some good conversation about films of that era offstage as well as on. Above you see Yuri analyzing, with his usual body English, a scene that he has made famous–a play with mirrors in Bauer’s King of Paris (1917).

The films

The last day of the symposium was devoted to two films that show how world film language changed between the mid-1910s and the early 1920s. Goro Masamune (1915) is a complicated tale about a swordsmith and the dramatic results of his mysterious parentage. It offered a stringent version of the sort of tableau staging we find in Europe and the US at the same period. As with those films, Goro Masamune used lateral staging and some striking depth effects, as well as long takes: I counted 58 shots and 24 intertitles across its 58 minutes.

With 356 shots and 25 intertitles, Roben-sugi exemplified a more cutting-based approach to cinematic storytelling. Scenes were broken down into many shots, often with a great variety of setups; the 180-degree system is in force; and many expressive effects were based on intercut close-ups. In the lengthy final scene, Roben, a temple bishop, discovers his long-lost mother and she prostrates herself before him. The action is played out in high-angle shots of the mother and low-angle shots of Roben. You couldn’t ask for better proof that filmmakers around the world were adopting the US continuity approach than this 1922 film.

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

These two movies were powerful treats, and the day was embellished with a visit behind the scenes to the Film Center’s staff area, where I got Yuri to shoot me with one of my favorites, Yamada Isuzu.

Earlier in the week, with Kyoko Hirano, I’d visited the Film Center to catch an item in its massive Makino Masahiro retrospective. Makino, son of Japan’s pioneering director Makino Shozo, directed films from the late 1920s to the early 1970s. For his centenary, the Center has mounted 100 programs of his work. No, that’s not a typo. The screenings include 110 titles directed or produced by Makino—and of course several others are lost. Japanese filmmakers are nothing if not prolific.

The film that Kyoko and I saw was Japanese Gangster Story 6: Sake Cup of the White Sword (1967), starring Takakura Ken. The plot consisted of intrigues crisscrossing rival gangs during the 1920s, capped by two bloody fights at the end. Ken doesn’t say much, but the camera loves him; early in the film he seemed to me to get the biggest close-ups. In the finale, of course he sacrifices himself for his gang boss. Is any genre cinema more standardized than the 1960s-1970s yakuza yarn? After a lunch of the Asakusa version of big Hiroshima-style omelettes, Makino’s buoyant retake on the classic tropes was a filling dessert.

The people

The third factor that has made this trip so pleasant has been the people. Hanging out with Yuri was great fun, and as luck would have it, Wisconsin film guy Michael Pogorzelski was visiting Tokyo at the same time. Mike is the archivist for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and he restores classic films for the AMPAS collection. (It isn’t all Hollywood, either: the archive is handling Satayajit Ray and Stan Brakhage.) Darkness and rain turned our trip through Shibuya into a scene out of Blade Runner.

Then there was Komatsu Hiroshi, who invited me to the symposium. Hiroshi is one of Japan’s top film historians, a man tirelessly committed to finding Japanese films and explaining their significance. He has made his appearance on this blog before. There was also Fujiwara Toshi, an exuberant young filmmaker I first met in Kyoto about ten years ago. Toshi has directed docs about Amos Gitai and other filmmakers, and his latest fiction film, We Can’t Go Home Again, played at the Berlin festival.

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

I’ve mentioned Kyoko Hirano, another former student and a best-selling author. Then there was my lunch with Donald Richie, hearty at 82 and planning more books, film screenings, and festival trips. His classic, The Inland Sea, is now being translated into Romanian. He gave me a copy of his newest, A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics and I reciprocated with a copy of Poetics of Cinema. Donald’s book is as delicate and sharp as a Basho lyric; beside it, my book looks like an andiron.

At the symposium I learned a great deal from Prof. Takemoto Mikio, director of the Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum at Waseda University, and the vice-director Prof. Akiba Hirokazu; Prof. Takeda Kiyoshi, who studied with Christian Metz; Prof. Nagata Yasushi of Theatre Studies; and many others who contributed talks and comments.

Finally, one more person, the one who spurred me to study Japanese cinema.

Ozu Yasujiro‘s gravesite is in Kita-Kamakura, about an hour southwest of Tokyo by train. In the summer of 1988, Kristin and I were led there by Donald, and so I was due for another pilgrimage. The day was cool and sunny, perfect for a brisk walk through the grounds of Engaku-Ji Temple.

At the end of my trip was the gravestone, which famously bears a single character: Mu, or nothing. Twenty years ago, two beer cans sat reverently on the stone, but today there was an opened bottle of sake. A cigarette lighter was tucked into a hole in the surrounding stone fence. Ozu, fierce smoker and professional drinker, was in his element.

On the platform and then on the train, I let my eyes drift among the schoolkids and the teenyboppers and the salarimen and the grave elders with hygiene masks. I began to imagine how Ozu, the poet of the transience of city life and the comic poignancy of human ties, would turn us all into cinema. He might put the camera over there, squatting on the floor of the traincar. That boy with the backpack might give a sassy reply to his father. Those two stylish office ladies sharing an iPod while a middle-aged man snores beside them–surely that’s a setup for a gag. Playing with the possibilities, one gaijin felt a pang of rapture at the blending of life and art.