Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.

Back in Vancouver

DB again:

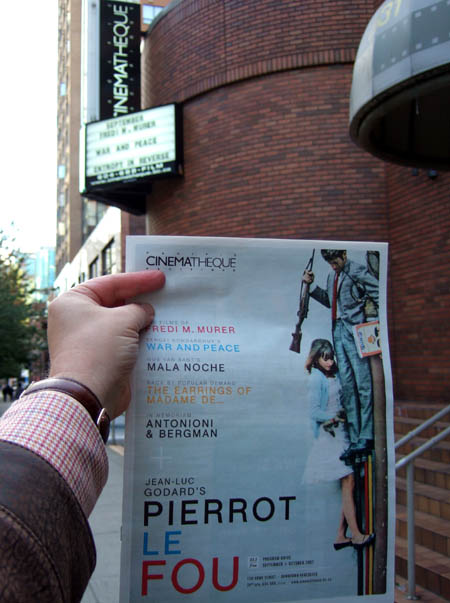

I sang the praises of the Vancouver International Film Festival in my first venture into blogging a year ago, so it’s a pleasure to report that this year’s event is no less captivating. Too many movies to take in, natch, so I’ll concentrate on two of the fest’s great strengths, documentaries and Asian films (programmed this year by both Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer). Top and bottom of today’s entry: glimpses of the two venues where I spend the most time: the Empire Granville 7 multiplex and the Pacific Cinémathèque a couple of blocks away, the latter offering ambitious programming to gladden the heart of any cinephile.

Two docus

10 + 4 (Iran) provides vignettes of Mania Akbari’s struggle to live with cancer therapy. The fact that she’s also the filmmaker, and that she starts, at Kiarostami’s suggestion, from the visual premise of 10, gives the film extra layers of interest. In fewer than seventy shots, most from within moving vehicles, the film presents a series of dialogues, usually between only two people. Since most major action takes place elsewhere, we watch and listen for signs of characters’ pasts, their relationships, and their states of mind.

We can trace Akbari’s development from cheery pride, going to parties despite her chemotherapy (“Every morning I thank God for make-up”), to anguish as the pain mounts and the treatments intensify. No viewer will forget the scene on a cablecar when she and Behnaz, from 10, reveal their different responses to their illness, and offscreen, examine each others’ mastectomies. In a final scene, Akbari, her hair now regrown, is confronted by another woman who warns her of using cancer as a weapon. The final words, heard under the credits—”I am using it, and I can’t give up the joy of this game”—reveal a psychological insight we rarely find in discussions of the social implications of illness.

Oatmeal-video visuals shot handheld and often out of focus, talking heads, dicey sound, overbusy editing—never mind. My Kid Could Paint That shows that we’ll forgive all sorts of technical faults if the subject, story, and ideas are gripping.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

It’s partly because, he shows, experts are pretty evasive when it comes to explaining how to tell good abstract painting from bad. Can’t you tell just by looking, as we can when we appreciate the figurative work of old and new masters? Turns out it’s not so easy. Critic Michael Kimmelman suggests, somewhat vaguely, that even abstract art is about a “story”—if not in the picture, behind the picture. Marla, of course provides a great story, but the question of how to judge her oeuvre remains.

We might insist that an artwork’s goodness is intrinsic, regardless of the circumstances of its making. If we learned on good evidence an eighty-year old woman had composed The Marriage of Figaro, surely it wouldn’t lose its sublimity. But philosophers Arthur Danto and Denis Dutton have suggested that our information about how an artwork came to be is usually relevant to interpreting and judging it. Sure enough, collectors rhapsodized about the work when they thought Marla had done it, but they cooled after a 60 Minutes story suggested that the father had coached her, and perhaps even finished the pieces himself.

That raises another issue, encapsulated by a Binghamton journalist. She explains that if a story is to run long in the media, it has to be given steep ups and downs. Hyped at the start, Marla’s paintings are suddenly called con jobs, and even Bar-Lev starts to get doubtful. How the family tries to regain their credibility, and how Bar-Lev exposes his own hesitations and complicities, makes for a fascinating film.

My Kid Could Paint That touches on other matters, such as the world’s love of a prodigy, the money that drives the gallery scene, and the issue of how much craft, such as skill in drawing, we now demand of our artists. What shines through the intellectual issues is a childhood joy in picture-making. As portrayed here, Marla remains a kid, and she reminds us of the pleasure in gooping up a surface with our fingers. Sony Pictures Classics made a wise move in acquiring this engrossing movie.

Turning Japanese

I try mostly to blog about films I like, passing over the others in silence. Hammer jobs are fun to write and to read, and I confess to having indulged in a couple when I felt that historical or stylistic analysis could cast light on current films that were being overpraised for originality. By and large, though, I prefer what Cahiers du cinéma called the criticism of enthusiasm. Everyone should write about the films she admires, and let history sort them out.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

Kitano is such an important filmmaker that you can’t ignore even something as offhand as this, but we have to hope for more.

Ten Nights of Dreams, a portmanteau feature based on stories by Soseki Natsume, is as uneven as these affairs usually are. The first chapter, a lovely episode by Jissoji Akio, is eerie in a subdued way, with some quietly canted compositions and some cutting reminiscent of the great Page of Madness. I also enjoyed Ichikawa Kon’s entry, a sober monochrome exercise. Most of the others, however, rely on turbocharged CGI and frantic grotesquerie—all justified by the indulgent premise that dreams are really, really weird.

Yamashita Nobohiro’s Matsugane Potshot Affair (2006), however, bowled right down my center lane. A crooked couple comes to a small town and their search for stolen bullion becomes one thread in a tangle of dysfunctional families and grubby sex. My last sentence does the film an injustice, though, because the laconic narration fills in the circumstances and backstory at such a leisurely pace that all your attention is on the grim comic byplay and furtive eroticism of the townfolk. Any movie that starts with a little boy feeling up what appears to be a woman’s corpse on a frozen lake signals its tone pretty straightforwardly.

As in Linda Linda Linda, the only other Yamashita I’ve seen (and mentioned here), the staging and shooting are quietly commanding. The shots average about 23 seconds, but they seem longer because the camera almost never moves. Lovely long takes with layers of depth and pockets of action captured in windows and paper doorways recall the great Japanese tradition of all-over composition. Yamashita provides several shots that could be filed in my gallery of funny framings. When you film this way, you have to know exactly where to put the camera, and several scenes—notably a confrontation among the thieves and the twin brothers—quicken areas of the frame we never normally notice. Movies like this remind you of the pleasure of having time to see everything.

I haven’t yet mentioned the film I enjoyed most, Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises, and today I’m also seeing the new Suo (I Just Didn’t Do It) and some other enticing items. So I turn Chinese, and Japanese again, in my next entry.

For more blogs anchored to the festival offerings, go here.

Tintin in movieland

For the number of films you can see on any given day, Brussels gives Paris a run for its money. It also has the advantage of efficiency. Several multiscreen repertory cinemas are within easy walking distance of one another, and normally the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique programs five different movies per day, plus a rotating program of another ten or so in another venue. For details on these venues, go here.

I’ve heard tales of Parisian cinephiles making the pilgrimage here to see films that their country had banned (e.g., Paths of Glory) or had not released in subtitled versions. I make my own pilgrimage every year, to watch films in the archive and to attend Cinédécouvertes, the annual festival that selects noteworthy items that don’t yet have a local distributor. For fifteen days, three titles are shown each night; you have two chances to see each one. It’s a great way to keep up with films that might not make it to the US or show up only on DVD.

The Cinémathèque, which runs the festival, provides prizes. A jury selects one or two best films, and a cash prize is awarded to a local distributor who agrees to acquire it. There’s also the Prix de l’Age d’or. Named in honor of Buñuel’s scandalous movie, this prize goes to a film that breaks with “cinematic conformism.” Past winners include Carlos Reygadas’ sober and disturbing Japon, Kornel Mundruczo’s frenzied hospital opera Johanna, and Paz Encina’s maximally minimalist Paraguayan Hammock.

The Palais des Beaux Arts is undergoing a huge renovation, and so the original venue, which I’ve visited almost every year for twenty-three years, is shut down.

The screenings have moved from this shell of a building to the Shell Building down the street. That location boasts a large foyer done in Postwar Euro Harmless Abstraction.

A much bigger venue than the old place, this is a fine auditorium, and attendance has been brisk.

Alas, using only one screen has cut the number of Cinémathèque programs considerably, but next year the renovated Musée will resume its two-screen, heavy-duty schedule. In the meantime, there are always Styx, Nova, Actors Studio, Movy Club, and Cinema Arenberg–with its admirable summer blitz Ecran Total.

A late arrival from Bologna, a heavy archive schedule, and persistent jet lag kept me from several films in the festival, most unhappily Harmony Korine’s Mr. Lonely. Of those I did see….

Shotgun Stories (Jeff Nichols, 2007) A man has two sets of sons by different wives, and the boys start to feud. A laconic US indie, apparently laid back but ready to spring into violence. I liked the unpretentiousness of it; quiet presentation of harsh conflict is often welcome.

The Optimists (Goran Paskaljevic, 2006) Five episodes set in today’s Serbia, with a popular comedian playing a different role in each one. It had that mixture of humor, melancholy, and fatalism that one finds in Eastern European films of the 1960s. A couple of the episodes seemed merely anecdotes, but one, about a crazed little boy taught by his parents to eat anything that appeals to him, is good dirty fun. Some lovely long takes, shot in digital video.

Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Thailand, 2006) I saw it in Vancouver last fall and couldn’t wait to see it again. Lyrical, finely paced, and unremittingly mysterious. A female doctor works in one clinic, a male one in another (now I get it); beyond that, the connections are teasingly obscure. A parallel-universe movie? A time-travel movie? Two halves of two uncompleted films? Political comment, though oblique, is there as well, most evident in a stockpile of artificial limbs in a hospital basement, adjacent to the military wing.

Mogari Forest (Kawase Naomi, Japan, 2007) Speaking of mystery, it’s ladled on pretty heavily in this Cannes Grand Prize winner. A woman working with the elderly in a care facility follows an old man into the forest; epiphany occurs. I have liked, mildly, Kawase’s earlier films Suzaku and Shara, but this one felt a little heavy-handed in its appeal to elemental forces. Still, the rhythm is engrossing, and it’s remarkably tactile, making you feel the dampness of loam and ferns.

Blue Eyelids (Ernesto Contreras, Mexico, 2007) At first I thought I was seeing a likable but unambitious commercial film about two lonely souls brought together. Then things slip sideways. A shy working woman wins a vacation trip for two, but she doesn’t really know anybody to ask along. She meets a former schoolmate and invites him. As they prepare for their holiday, their relationship becomes freighted with emotional investments. Nicely managed shifts in point of view both reveal and hide key information, and we get fine performances. But was the bird symbolism really necessary?

This year’s winners were Mogari Forest and Hotel Very Welcome (Sonja Heiss, Germany) for best films (10,000 euros each) and La influencia (Pedro Aguilera, Spain/ Mexico) for the L’age d’or prize (5,000 euros). Above, Cinémathèque director Gabrielle Claes introduces the jury.

Next time: Visiting the archive and checking out local cinemas (at last I catch Inland Empire). Maybe some beer as well.

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…