Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Bando on the run

Sakamoto Ryoma (1928).

The Matsuda Eigasha company of Tokyo deserves enormous credit for restoring and making available classic Japanese films. My first visit to the firm twenty years ago was a revelation. Matsuda Shinsui was a former benshi, or spoken-word film accompanist, and he and his sons were collecting old films so that he could accompany them in screenings. A great many of the films were chambara, or swordfight movies. Most survived only in fragments, but what tantalizing fragments they were! (1)

The company made several of the films available on VHS tape, accompanied by benshi commentary prepared by Mr. Matsuda. I came away with several of these treasures. On later visits I was able to watch some films that hadn’t been transferred to video, and several of those deserve to be more widely seen.

When Mr. Matsuda’s son kindly drove me to my train station, I noticed that his car had a VHS player and video monitor installed in the dashboard. So much for my Tokyo-ga experience.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

In 1979 Matsuda Eigasha compiled a documentary on the swordplay star Bando Tomasaburo. Now Digital Meme has made it available on DVD, complete with English subtitles. Bantsuma: The Life of Tomasaburo Bando is obligatory viewing for everyone interested in Japanese cinema. Not only does it handily trace Bando’s remarkable career through stills, interviews, and surviving footage. It also supports something I’ve tried to show for some time: that the Japanese action cinema of the 1920s and 1930s was one of the most powerful and creative trends in world filmmaking.

Action and innovation

Some writers have thought that Japanese filmmakers were developing a culturally anchored approach to filmic storytelling independent of Western influences. But in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and two essays in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema, I argue something different. By the early 1920s Japanese filmmakers had mastered Hollywood’s norms of visual storytelling. In the Matsuda documentary, this is evident from the clips from early Bando films like Gyakuryu (1924) and Kageboshi (1924). Long shots are broken up into closer views, and conversations are treated in reverse-angle shots of speaker and listener. Camera movements follow the characters as they walk or run.

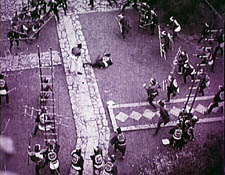

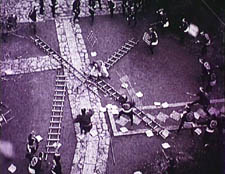

So far, so conventional. But many Japanese filmmakers revised the American approach, turning it into something more expressive and experimental. So, for example, a very steep high angle in Kirarazaka (1925) serves at first to show us that Bando is surrounded by fighters who use ladders to try to trap him. As the scene returns to this framing again and again, it becomes more abstract, with the fallen ladders becoming vectors of a geometrical shot design targeting the hero.

An even more remarkable example is Orochi (1925), a Bando film that survives intact and in fine shape. (Matsuda released it on VHS; I don’t think it’s on DVD yet.) The clip in the 1979 documentary shows one of Orochi‘s most dazzling passages. The hero, played by Bando, fights his way through a town, and, backed up against a wall, he’s trapped on all sides by his opponents. An extreme long-shot (below) shows us the situation, with Bando in the distant center. Many shots break this space down into opposing forces, Bando versus his adversaries, and quite fast cutting shows the men on either side of him.

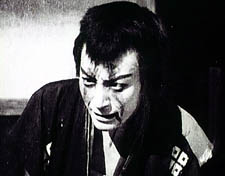

The stretch that interests me most begins with a shot of Bando looking left.

The director Futagawa Buntaro then breaks the confrontation into separate shots of the other swordsmen. Nothing unusual about that. But most directors would have handled the next few shots of the standoff this way:

Shot of Bando looking left.

Shot of a combatant looking right (implicitly, back at him).

Shot of Bando looking right.

Shot of a combatant looking left (implicitly, back at him).

This way we’d get a clear, simple sense of the fact that he’s surrounded on all sides. Instead, Futagawa follows the shot of Bando looking left with no fewer than twelve very close shots of fighters, all looking rightward. For example:

Then we get six shots of their arms outthrust, as here:

We then get a shot of several men looking straight to the camera, as if they represent the group directly in front of Bando, no longer at the left. Next there appear another ten shots of fighters looking leftward at Bando, all of them quite close to the camera. For example:

In both sets of shots, many images are composed to match each other graphically: the first group of faces tends to place each man on the left frame edge, while the second set puts most men at the far right. The first set of shots develops a pattern, moving from tight facial close-ups to shots of arms and swords thrusting toward Bando. The second set develops toward showing faces that are ever more cut off by the right frame edge.

Add in the fact that all these shots are cut very quickly, ranging from four frames down to one! This is extraordinarily rare in 1925 cinema. (I talk more about how to study such passages in an earlier blog.) Words can’t really convey the way these images clatter against one another. Their percussive speed makes them graspable only as a tense thrust in one direction countered by an equally tense one opposite. Faces pile frantically up against Bando first one one side, then the other. The sense of linear force is strengthened by the shift from the cluster of face shots to that of the arms, with the transition handled in a pair of weird jump cuts along different men’s arms.

The transition from the first shot above to the second creates the impression that the man has jabbed with his spear, while the cut from the second to the third shot eases us to the forearm shots shown earlier.

This bravura passage is triggered by the initial shot of Bando, haggard and shaky. Perhaps the cascade of shots is motivated as subjective, reflecting his exhaustion in the face of entrapment. Just as likely, I’d say, is the fact that Futagawa took a stereotyped situation, the hero surrounded by his adversaries, and looked for a way to make it fresh, to use energetic stylistic innovation to amplify the story point emotionally and perceptually.

Nothing in the sequence violates continuity editing’s basic principles. The shots keep screen direction constant and character position clear. Indeed, the director has understood spatial continuity very deeply: the men to the left of Bando are pushed far to the left side of the frame, the men to the right are squeezed rightward, so that Bando is always implicitly filling the area they’re recoiling from. But what American director would have risked such a bold piece of cutting?

Orochi, let’s remember, was released the same year as Strike and Potemkin. If this passage had been known to the earliest generation of film historians, Japan might well have been greeted as another birthplace of daringly dynamic montage. (2)

There are several other intriguing flourishes in the footage on display in Bantsuma, particularly a scene of Bando dying in a swirl of steam (this entry’s top image). But two points should be clear: this is innovative filmmaking of a high order, and it took place in a shamelessly commercial film industry. Mainstream filmmaking in Japan has been open to stylistic experiment to a degree rare in other popular cinemas. You can trace a line from the 1920s to the present, from the chambara directors through Ozu and Mizoguchi and Kinoshita and Suzuki Seijin right up to Kitano and Miike. Along a parallel path, Hong Kong action cinema pressed filmmakers toward creative renovation of film technique. (3) In this tradition, the action films of Bantsuma and his peers hold an honored place.

The lessons are familiar ones from this blog. Mass-market cinema harbors experimental impulses; creative directors working in well-known genres are often striving to push the limits. By attending to technique, we can discover a dazzling variety in areas of film history not usually considered “artistic.”

PS: Through Digital Meme, Matsuda has also made available a treasury of 55 animated films from the earliest years. The are at work on a DVD of early Mizoguchi films, including a fragment I’m keen to see from Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner, 1930).

(1) A large set of them has been available for some years on a DVD-ROM, also available from Digital Meme. For useful reviews, go to Midnight Eye and hors champ.

(2) ) I offer several other examples in the essays “Japanese Film Style, 1925-1945” and “A Cinema of Flourishes” in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.

(3) I make this argument in Planet Hong Kong and the essays “Aesthetics in Action” and “Richness through Imperfection” in Poetics of Cinema.

A many-splendored thing 9: On, and over, the edge

Films from the Fragrant Harbor

Sorry to be late with this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival. The last three days have been mighty busy, including a morning of roundtables with journalists and local critics, a supper with Mr and Mrs Johnnie To, an encounter with Ringo Lam, and other escapades. Plus heavy viewings of classics by Li Han-hsiang. I hope to blog about all this before I leave on Thursday. In the meantime, I’ll catch up on what any good festival is about…the films. Or rather, the ones I’ve liked most in the last few days.

Paolo Gioli has been making experimental films since the 1960s. From one angle, his approach converges with the work of filmmakers like Ken Jacobs and Ernie Gehr. Gioli employs optical printing and other techniques to halt, fragment, and superimpose images, many of them from found footage. Perforations flutter across the screen and framelines dance; single-frame montage imparts hallucinatory movement to a static picture; negative and positive images bounce off one another. The very concept of a shot or of a film frame dissolves in this lovely work.

But Gioli’s originality goes beyond the tradition of recasting found footage. Anticipating recent gallery artists who rig up their own movie machines, he films with pinhole cameras made of buttons or seashells, or uses leaves to create an extra shutter. The results can be aggressive or lyrical, and I found them completely fascinating. The first of four programs of his work was my first sight of Gioli’s work. How could I have missed it?

All the five films in the set, mostly from the late 1960s and early 1970s, were very impressive. In Traces of traces (1969), the abstract whorls and speckles are made from filmstock pressed upon his skin and fingertips. According to My Glass Eye (1971) assaults us with a flurry of Muybridge-like postures and fluttering close-ups, all to a threatening drumbeat.

My favorite was the gentler Anonimatograph (1972), recomposed from a 35mm home movie from the 1910s and 1920s. The shots settle into layers, and as they peel off we see people in different phases of their lives, sometimes studying each other across the years. Family portraits become eerie silhouettes and cameos. Even gouges on the emulsion serve as testimony to time gone.

Mark McElhatten, an expert on experimental film, provided the catalogue essay and an enlightening introduction to the screening, as well as an after-film discussion. He pointed out Gioli’s fascination with the textures of the human body as they are shaped by time and space, and then captured on the skin of film itself. Film as a tactile medium: No surprise that Gioli is also a sculptor.

You can read more about his work in Mark’s detailed essay for a Lincoln Center retrospective. This is Gioli’s suitably sparse website, and here is a site offering a DVD collection (unhappily not including Anonimatograph).

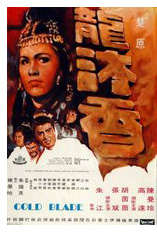

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade (1970) is a very different affair. This swordplay classic directed by the versatile Chor Yuen for Cathay has been fairly hard to see. (My first viewing came in 1997, at a Brussels retrospective.) The print screened by the HK Film Archive was restored from a Cathay negative, supplemented by sound from a copy held by Marie-Claire Quiquemelle of Paris. The result was a stunning print with vibrant color. The story of the restoration can be found here.

Cold Blade begins with a graceful title sequence showing our two heroes practicing their signature moves in slow motion and floating aerobatics. These maneuvers will of course prove important at the climax. The story was written for the screen, but it’s as full of twists and double-dealing as a martial-arts novel. The cutting is frantically fast (average shot length of 4.4 seconds!) but always intelligible. Chor Yuen provides his characteristically crammed fight scenes. His long lenses create layers of pulsing foreground movement that yield intermittent views of his protagonists. All in all, a satisfying reminder of the first golden era of Hong Kong action film.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Then there was Baba Yasuo’s Bubble Fiction: Boom or Bust (2007), an international premiere that drew huge crowds and big laughs. Here’s one Asian film that won’t be remade in Hollywood; it’s already an unembarrassed riff on Back to the Future. Mayumi, a ditzy bar hostess, tries to prevent Japan’s financial collapse by returning to 1990 and blocking corrupt legislation. Her vehicle: a lemon-yellow Hyundai washing machine.

Naturally, Bubble Fiction is filled with retro music, dances, fashions, and hair styles, with plenty of in-jokes about J-pop culture and references to its Hollywood source. “Don’t tell me you came in a DeLorean?” a skeptic asks our heroine. Bubble-era Japan is tellingly satirized, with profligate salarymen in loose suits lined up and waving banknotes to flag down cabs. The director painstakingly reconstructed the Tokyo of the time, including elaborate desserts and hand-punched train tickets.

Of course catastrophe is thwarted, and Mayumi comes back to a sunnier future, having gained a father and a new place in the community. Lighter than air, full of ingratiating gags, and cleverly crafted on Hollywood’s script model, Bubble Fiction proved just the sort of good-natured movie that I needed after 3 ¼ films earlier that day. Fragrant Harbor filmmaker Tsui Hark once wisely remarked: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

For credits and further info, check out the Pony Canyon site and Russell Edwards’ Variety review.

In the wake of Infernal Affairs, Hong Kong movies have been filled with undercover cops turning confused, bitter, and suicidal. On the Edge (2006) from the Herman Yau retrospective here at the festival, is one of the very best. Like Yau’s From the Queen to the Chief Executive, this starts from a social fact: Most moles returning to duty don’t last more than a few years. Why? On the Edge explores the possibility that the friendships forged in the underworld are more authentic and durable than the stern bureaucracy of law and order.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

The film begins with mole Nick Cheung betraying his father-figure Francis Ng. When he tries to readjust to life in the force, other cops keep away, Internal Affairs bureaucrats trail him, and he’s kept out of the loop. His new partner Anthony Wong goads him and flagrantly pounds up suspects, as if to prod Nick into defending the lowlife he once moved among. He sinks into alcoholism and tries to win back his girlfriend. A finely judged scene shows him revisiting a nightclub at which he’d once won the Triads’ trust. He shifts awkwardly between the bravado of a gang member and the panic of an outgunned policeman.

Thanks to a flashback structure, we see Nick’s rise in the gang juxtaposed to his slump once he’s back in uniform. Without being heavy-handed, the film juxtaposes a scene of Nick trying to return to civilian life with a parallel moment in his Triad days. It isn’t easy to advance two stories at once, but Yau manages it easily. There are also many sharp character bits, expressed—as customary in Hong Kong films—through confrontations and combats. A scene in nightclub builds tension as Ng and Wong, crook and cop, seize karaoke microphones to bark challenges to one another.

Without recourse to the flourishes of a certain Hollywood film on a similar theme, On the Edge exposes the anguish of a man cut adrift from the world that gave him his identity. Simple and modest, but with subtle touches (watch out for the disabled man on the handcart), Yau’s B-film aesthetic deals straightforwardly with plot, character, pungent locations, and a fine cast. You don’t need portentous symbols like a rat skittering along a condo railing. Just tell the story of one man who lost himself.

A many-splendored thing 5: Sampling

Sakuran.

From DB:

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

While I’ve been here, Hong Kong has been embroiled in two big stories. First is the runup to the election for chief executive. Hong Kong has indirect elections, whereby groups purportedly representing constituencies, chiefly various business interests, are in turn represented by electors. On the day of the vote, I saw several demonstrations demanding both new environmental policies and universal suffrage. So much for the myth that Hong Kong people don’t participate in politics.

Current chief executive Donald Tsang Yam-kuen, Beijing’s appointee, won the election, with 649 votes out of 789 voting members. Tsang has promised to introduce direct voting and universal suffrage by 2012. We’ll see.

The other big story has been the aftermath of a 2006 shootout involving police constable Tsui Po-ko. The latter has the confusing intricacy of a Hong Kong cop movie. Some years ago Tsui allegedly killed another cop and stole his pistol; a year later he robbed a bank. (The Economist offers a summary here.) An inquest has been under way. Wednesday’s South China Morning Post (not available free online) reports on the contents of Constable Tsui’s notebooks. There are indications that he was tailing political figures and calculating how an ambush might be carried out beneath traffic underpasses.

The media have gone wild over this and even replayed the episode of the local version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? on which Tsui appeared as a contestant. Today’s edition of the SCMP reports an even weirder turn. An FBI expert has testified that Tsui suffered from schizotypal personality disorder. This is characterized by “social isolation, odd behavior and thinking, and often unconventional beliefs.” Sound like you or me?

Moving to the more comforting world of cinema, let me catch up on some of the films I’ve seen at Filmart and the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Ying Liang’s The Other Half: A shrewdly constructed story about a young woman with marital troubles who becomes a legal stenographer. Ying interweaves her life crises with the monologues of locals who come to seek action from the lawyer. These incidents were derived, Ying explained in the Q & A, from actual cases the non-actors knew. Ying collected over 100 law cases and then showed his script to lawyers and legal professionals, some of whom appeared in the film. Single-take scenes predominate, making good use of the deep-focus capacities of digital video. A vivid angle into ordinary life in China, with insights as well into problems of industrial pollution.

Li Yu’s Lost in Beijing: Less interesting, I thought. A fairly traditional melodrama involving an innocent woman caught between two macho men, husband and boss, and the boss’s scheming wife. The glimpses of life in Beijing were more valuable than the supposedly scandalous sex scenes that feature heavily in the early reels.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Derek Yee’s Protégé: Yee is a mid-range Hong Kong director who can turn out solid entertainment and sometimes, as with One Nite in Mongkok, some social criticism. In Protégé, you know you’re in for a rough time from the start. A smack-addled mom staggers onto a sofa to die, and her little girl waddles over to yank out the needle and drop it carefully into a wastebin. Whether you love or hate The Departed, Protégé reminds us that Hong Kong film can chop closer to the bone than anything from our purportedly hard-edged directors.

Daniel Wu plays an undercover cop who’s taken years to become virtually a son to drug kingpin Andy Lau. Their intriguing relationship counterbalances Yu’s efforts to wean an addicted mother off the stuff. There are some fascinating quasi-documentary scenes of cooking heroin and harvesting Thai poppies. The parallels between the drug addicts whom Andy despises and his own need for shots of insulin are insinuated, not slammed home. Yee mixes grim realism with some showy melodrama, adding an explosive drug bust. (That sequence contains a startling shot that in itself justifies the existence of CGI.) Despite an overlong denouement and a few loose ends, the film seems to me better than the average local genre fare.

Ninagawa Mika’s Sakuran: Anachronism has a field day in this story of a cunning girl’s rise to be top geisha. Riotous sets and costumes, along with big-band swing music, create the suffocating but ravishing world of courtesans and their patrons. A sentimental ending telegraphed far in advance, but no less welcome for that.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Nicole Garcia’s Selon Charlie: Screened in Filmart, this 2005 pic seemed to me a solid if somewhat academic drama. A network narrative about a fugitive archaeologist in a town full of philandering husbands and bored wives, it’s your basic bourgeois life-crisis tale, decorated with parallels to a mysterious hominid found at a dig site. It has the usual Eurofilm tact and shows how the French have adapted Hollywood’s screenplay structure to fit the well-upholstered stories they like to tell.

Benoît Delépine and Gustave Kervern’s Avida: Black and white almost throughout, in 35mm that looks like muddy 16, this surrealist pastiche starts strong. Early scenes offer a new riff on Tati’s Mon Oncle, in which a toff returns to his cyberautomated mansion and encounters problems with dogs and plate glass. Then we’re in Buñuel-Carrière territory (Carrière is in the movie), as a dognapping leads to an amazing scene of pooch decapitation. Things seemed to me to drag as the episodes got sillier and less visually expressive. Rhinos, lions, elephants, big beetles, and a highly diverse sampling of the human species do walk-ons. Not so much metaphysical as pataphysical.

Iran: A Cinematographic Revolution: A documentary on the pre-1990s Iranian cinema. It’s informative, cautious about the role of the mullahs, and filled with intriguing clips from Hollywood-style melodramas and the neorealist-flavored efforts of the 1970s. Good talking heads too (though no Kiarostami). The film reaffirms how single-mindedly the cinema agencies pursued film festivals as a way of increasing the profile of the nation’s culture; the motto was “No festival without an Iranian film.” But can Iran really have trained a total of 90,000 film-related workers, as the docu says?

Johnnie To’s Exiled: I hadn’t yet seen it on the big screen. That’s where it belongs. The first sequence evokes Once Upon a Time in the West‘s opening, and it’s followed by an exhilarating, utterly implausible gun battle. Watch out for that spinning door!

When Mr. To previewed this opening for me last spring, I didn’t think he could top it, but he does. The later scene in the underground clinic will rank with one of the great action sequences of all time. I won’t spoil it for those who haven’t seen it by previewing a still. Let’s just say that To finds fresh compositional tactics in close quarters, as in the hotel climax.

Full of visual invention and neat character bits, Exiled shows that To keeps trying new things. I wrote a little about To’s style in an earlier post, and some backstory on the Exiled rooftop sets can be found here.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

Cheang Pou-soi’s Dog Bite Dog: This tale of a hired killer from Thailand and the raging young cop who pursues him presents a world in Hobbesian frenzy, with all against all. The most unrelentingly violent Hong Kong film I’ve seen in years, Dog Bite Dog starts with imagery of the killer hiding in the bowels of a ship, scraping up flecks of rice from the floor. After consummating his hit, he moves through a landscape of garbage, hiding out in a landfill and rummaging in a recycle bin for scraps to doctor a girl’s wounded foot. I don’t know any film that insists so intently on the textures of urban offal.

The cop trembles under the pressure of his own torments, and the parallels between the two men climax in a knife fight in a crumbling Thai temple. As is often the case in local cinema, Father is to blame. This visceral movie surely couldn’t be released theatrically in the US. Even the most jaded action aficionado is likely to flinch from certain scenes.

Cheang’s previous film is the suspenseful Love Battlefield. Of Dog Bite Dog he remarked, “I wanted to show [the audience] this Hong Kong film that does not have choreographed action.” For more, see Grady Hendrix’s coverage here and Twitchfilm’s longish review.

Otar Iosseliani’s Gardens in Autumn: The first shot, in which old men quarrel over which one gets to buy a cheap coffin, puts us firmly in Iosseliani’s parallel universe. As often, he speaks for those who just opt out. A minister of agriculture loses his post and drifts among ne’er-do-well pals, hookers, and girlfriends. A film about drinking, eating, smoking, rollerblading, music-making, and middle-aged sex, Gardens in Autumn also satirizes the rich, who are just as lazy as our heroes but waste their lives shopping. There are also prop gags, including the pictures of heifers and boars that show up in quite unexpected places.

Iosseliani casts himself as an easygoing gardener who draws cartoons on a cafe wall. Some of these images recall people and shots we see in the movie, as if we’re watching the old buzzard create the film between swigs of vodka. An elegiac poem to the subversive force of idleness, with a final scene celebrating women.

Over the next couple of weeks, more frequent posts, I hope, including glimpses of this highly photogenic city. For the moment, this from a double-decker bus must suffice.

Welcome back, Suo-san

Suo Masayuki, one of Japan’s most ingratiating directors, found an international triumph with Shall We Dance? (1996). He had started his career with an odd little softcore porn film, Abnormal Family (1983), shot as an admiring pastiche of Ozu’s style. His Fancy Dance (1989) was also fun, but he really hit his stride with Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (1992), which remains a sure-fire crowd pleaser.

Suo worked comic variations on an ingenious theme: How Japanese youth fail to appreciate the beauty of their traditional culture. The garage-band ska singer in Fancy Dance is obliged to retreat to a monastery, where he discovers that Zen is really, really cool. Sumo Do converts sullen college kids to the virtues of ritualized wrestling. Shall We Dance? works in reverse, obliging an uptight salaryman to rekindle his marriage by learning ballroom dance. Suo’s films celebrate pleasurable fusions between Asian and Western cultures.

Suo’s meticulous, understated style is a kind of modern revision of Ozu’s. Fancy Dance and Sumo Do pay homage to the master’s college comedies, and in Shall We Dance? the first tracking shot occurs when the hero takes his first tentative dance steps. In Figures Traced in Light, I mention Suo as part of that trend toward planimetric shooting and compass-point cutting I discussed in an earlier blog. As you see from the opening images, he tries out the precise sort of graphic matching between shots that was a hallmark of Ozu’s style.

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

Suo has been very quiet for the last decade, but now he’s back. I Just Didn’t Do It is arousing keen local interest, partly because of its controversial subject matter. Japan is known as a low-crime society, but gradually questions of police brutality have emerged. Suspects can be kept in custody for up to 23 days, and unique among industrial nations, 95% of all people arrested confess!

In Suo’s new film, a young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl in the subway. It’s a daring move for a director known for light comedies. The film stars Kase Ryo, from Letters from Iwo Jima, and veteran Yakusho Koji, seen most recently in Babel. Read more about it here, noting that the Economist’s contents tend to evaporate into the pay-only archive. The film’s official website, in English, is here.

I Just Didn’t Do It, Suo says, is a film “I simply had to make.”