Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Walk the talk

The Magnificent Ambersons.

“It’s only history,” Jack Valenti is reported to have said when allowing scholars access to MPAA files. (1) After studying Hollywood for over thirty years, I should be used to the ways in which trade journalists (and some critics) forget or ignore historical precedents in moviemaking. But I still get bug-eyed when I encounter something like the Variety piece on TV director Tommy Schlamme (Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip).

The subhead tells us that this DGA nominee is known for his “hallway shots.” That gets my interest.

I lose interest fast. The writer tells us that Schlamme

developed the “walk and talk” on Sports Night and then mastered it on The West Wing.

The shot—which features two or more actors moving from one location to another on the set, often from one office to another via a hallway—has become a Schlamme signature.

The first sentence could be read as saying that Schlamme invented the walk-and-talk. Since I spent a little time studying this technique in The Way Hollywood Tells It, my inner film historian cries out, Aarrgh. Long before Sports Night (aired 1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), movies were developing such bravura shots.

The oblique view

In the prototypical walk-and-talk, two or more characters advance, and the camera tracks along, keeping them centered as they move through the environment. Such shots are quite uncommon in the silent cinema, but they emerge in 1930s films from many countries.

They were truly “signature shots” for Max Ophuls and the lesser-known Erik Charell. In Charell’s captivating The Congress Dances (1931) Lillian Harvey sings while a carriage takes her through an entire town and into the country, all in flowing tracking shots. Call it a ride-and-sing.

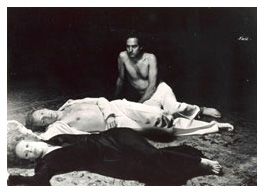

If that’s not as pure an instance as you’d like, we can find nice ones during a street scene of The Thin Man (1934). A more somber example occurs in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), with the camera in a river bed angled upward at the couple it follows.

Usually such traveling shots from the 1930s and 1940s are shot obliquely to the actors. That is, the performers are seen in a ¾ view, and they walk along a diagonal path with respect to the frame edges; the camera moves on a similar trajectory. Sound cameras were mounted on dollies that usually ran on tracks. Framing the actors head-on raised problems with this gear. Performers couldn’t walk smoothly if they were stepping within rails, and there was a risk that the rails in the distance might appear in the frame. It was simpler to set the camera at an oblique angle so that actors could walk unimpeded and the tracks wouldn’t be seen. Directors continued to use this framing into the 1950s, as in Welles’ Othello (1952) and Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957). Both are unusually long takes; in the second, poor Gene Barry seems to be panting to keep up with the other men.

Back off

Today’s walk-and-talk is more likely to be a head-on framing, with the camera retreating from the actors. (More rarely, it dogs them from behind.) With a retreating Steadicam, you don’t have to worry about glimpsing the ground or floor behind the actors, in the distance, since there are no track rails to be exposed. Again, though, we have some precedents, most famously the splendid camera movements, evidently executed with a crane, in the ball sequences of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), when George and Lucy stroll through the party.

When location shooting became more common in the 1940s and 1950s, cameras could be supported on more versatile dollies that didn’t require track rails, and these reverse-tracking shots become a bit more common. Kubrick, highly influenced by Welles and Ophuls, captured his officers striding through the trenches of Paths of Glory (1957). Vincent LoBrutto’s information-packed book (2) tells us that Kubrick’s dolly rolled backward on the planks that the actors walked on (authentic details, as boards were indeed used in the muddy trenches). Godard’s long traveling through the office lobby in Breathless (1960) was shot from a wheelchair.

Such head-on (and tails-on) shots can be found in several films well into the 1970s, as in Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1970). In fact, hospitals, police stations, and other sprawling institutional spaces seem to invite this approach.

By the 1980s, these shots proliferate in American films largely because the Steadicam makes them easy. One famous example is De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), which follows the drunken Peter Fallow through a hotel as he picks up and drops off many other characters.

Today such shots are very common in both high- and low-budget films. Schlamme’s “signature” device seems to be in pretty wide circulation. At best it’s a convention, at worst a cliché.

They’re called actors; let them perform action

I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that walk-and-talk is one of two principal staging techniques of contemporary Hollywood. The other, usually called stand-and-deliver, plants the characters facing one another and simply cuts from one to the other. The scene is built primarily out of singles (shots of only one actor) or over-the-shoulder framings. Here’s a typically static dialogue scene from The Matrix Revolutions (2003).

Both stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk began in the studio era, decades ago, but then there were other options as well. Directors cultivated smooth, unobtrusive blocking tactics that moved characters in ways that reflected the developing scene. The actors had to perform with their whole bodies, and bits of business motivated them to circulate through the setting and turn toward or away from the camera. One example given earlier on this blog is from Mildred Pierce; here’s another, from the program picture Homicide (1949).

Detective Michael Landers has a hunch that the purported suicide of a former sailor is really murder. He has to persuade Captain Mooney to let him pursue some leads out of his jurisdiction. Today this might be played out in a stand-and-deliver session, with both men seated and shot/ reverse-shot cutting carrying the scene. But the director Felix Jacoves decides to let his actors earn their money through ensemble staging, not merely line readings. Here are just three shots from the middle of the scene that illustrate my point.

Landers stands at Mooney’s desk and gets a refusal. As he turns away to the left, Mooney walks to the rear files to put the papers away.

As they’re retreating to the opposite ends of the screen, Landers’ partner Boylan, who’s been offscreen for this phase of the scene, strides into the center and pauses at the door. The result of this choreography is both a balanced three-point composition and a chance to let us observe Boylan’s skeptical reaction to Landers’ next plea.

The camera tracks in as Landers approaches Mooney. Boylan shifts closer as well. What seems somewhat stagy as we analyze it doesn’t look obtrusive on the screen, because we’re following Landers’ arguments and watching the older men’s reactions. The closer framing and the position of the men, now face to face rather than separated by a desk, raises the dramatic pressure. As Landers pauses, Mooney folds his arms—a simple piece of body language that lets us know he’s still resisting.

Now a cut to Mooney, in an OTS framing, stresses his continued resistance as he tells Landers off, and a reverse shot gives Landers’ angry reaction.

Interrupting the sustained take, the shot/ reverse shot cuts have gained more emphasis than if they were part of a string of OTS shots. Jacoves has saved his cuts and closer views for a moment that raises the stakes visually as well as dramatically.

I’m not claiming that this is a brilliant stretch of cinema. (But you have to like a plot in which the hero defeats the killer by denying him access to insulin.) It’s just that the sequence activates, in a way that directors once took for granted, aspects of film art that we don’t find too often nowadays. Once you didn’t have to choose between Steadicam logistics and static dialogue; there is a very wide middle ground if you’re willing to move actors around the set and give them some body language and prop work. No need for a walk-and-talk here.

Schema and revision

The Variety article explains that Schlamme utilizes his long walk-and-talks to save time and money. But directors in the studio era shot their fully elaborated scenes like that in Homicide to be economical as well. If actors know their lines and hit their marks, playing out pages of dialogue in a few sustained setups can be very efficient; the Homicide full shot consumes 45 seconds. I’d argue that most contemporary directors have never learned to stage scenes this way. It’s a lost skill set. I make the case in more detail in Figures Traced in Light and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

To some extent, however, another skill set has emerged. Some walk-and-talks in The West Wing and other programs have an extra feature that the Variety writer and I haven’t mentioned. Often character A and B are walking toward us down the corridor, then B drifts off and C catches up with A. A and C walk for a while, then A peels off and C picks up somebody else, and so on. This approach is suited to multiple-protagonist dramas. You can show the plotlines crossing and separating.

I’m no TV historian, but I think that this technique showed up on St. Elsewhere (1982-1988), and it’s definitely on display in ER (1994-). Hospitals again. I think we also find this mingling/ separating choreography in contemporary film, but I can’t recall many examples in earlier eras. You could argue that one of the shots in the Ambersons’ ballroom does this, though I don’t think it’s a pure instance. (The principle of overlapping character actions is at work in many Renoir films, most famously in the final party melee in Rules of the Game, but Renoir doesn’t employ what we’re calling a walk-and-talk.) Did movies pick up this intertwined walk-and-talk from TV or vice-versa? I don’t know. If you do, drop me a line!

In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I argue that stylistic change in filmmaking often follows a logic of what art historian E. H. Gombrich calls schema and revision. (3) A pattern or practice becomes standardized, but then creators extend it to new situations or find new possibilities in it, and they modify it.

Camera movements have long been used to link characters. For instance, when Nick Charles circulates drinks in The Thin Man, Van Dyke tracks leftward to follow him from guest to guest.

So maybe in the 1980s and 1990s, when ensemble stories had to balance attention among several major characters, directors blended the multiple-interaction aspect of lateral camera movements with the schema of the advancing walk-and-talk. The result makes characters move in and out of each others’ orbits along a single trajectory. Whoever came up with this device, I’d speculate that it arose from the realization that the backing-up walk-and-talk could be repurposed for dramas following the fates of several protagonists.

It’s only history, but it matters if we want to understand stylistic continuity and change.

(1) Thanks to Richard Maltby for passing this along.

(2) Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (New York: Fine, 1997), 141-142.

(3) E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, N. J. Princeton University Press, 1960), especially Chapter III.

Updates and outtakes (in which we try, perhaps in vain, to catch up with ourselves)

Exiled

Kristin writes:

“The Hobbit Film: New Developments” (January 13, 2007)

In this entry I discussed Bob Shaye’s recent claim that Peter Jackson would never get a chance to direct The Hobbit for New Line. I mentioned that one of the factors involved in the negotiations about who would direct is that the production rights will eventually revert to producer Saul Zaentz. I didn’t know the length of the option on those rights, which New Line currently holds. The January issue of the fantasy/sci fic magazine Locus says that the rights will revert to Zaentz in 2009.

Zaentz had owned the rights since the mid-1970s and sold them to Miramax in early 1997. Miramax had the two-film version of The Lord of the Rings in pre-production for about 18 months and then sold the rights to New Line in August of 1998. I don’t know what the source of Locus’ information is, but a twelve-month option would seem pretty plausible.

If that information is correct, New Line only has about two years to get the actual making of the film underway. It takes years for any big film to lumber into production in Hollywood these days, so the studio doesn’t have a lot of room to wiggle.

“By Annie Standards” (December 14, 2006)

Here I talked about methods for publicizing animated features. One way, I suggested, would be to foster audience interest in the various animation awards other than the Oscars. I remarked, “Under Academy rules, only three animated features can be nominated in any year unless sixteen or more such features are released that year. Then the number of nominations jumps to five, but so far that hasn’t happened. It may finally happen this year, if all sixteen features currently under consideration qualify under Academy rules.”

Close, but not close enough. On January 11, Variety announced that one film, Luc Besson’s Arthur and the Invisibles, had been disqualified as an animated feature. To qualify, a film must have at least 75% animated footage, and Arthur has too much live action.

With the number of qualifying features down to fifteen, only three can be nominated. Probably Cars will win, as I predicted in the original entry. It just won the Golden Globe in the newly established Animated Film category.

“Snakes, No, Borat, Yes: Not All Internet Publicity Is the Same” (January 7, 2007)

Here I suggested some reasons why Snakes on a Plane failed at the box office and Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan succeeded, despite the fact that both garnered considerable fan-generated publicity on the internet. I mentioned that Sacha Baren Cohen had appeared on talk shows in character as Borat rather than in persona proper: “Each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.”

Trying to correct the widespread assumption that Borat was an improvised film, the January 8-14 issue of Variety ran a story about how Cohen worked with three scriptwriters, Peter Baynham, Dan Mazer, and Anthony “Ant” Hines: “The scribes even concoct Cohen’s dialogue for his promo appearances on ‘The Tonight Show’ and ‘Live With Regis and Kelly.’” Although Cohen presumably ad-libs to meet specific circumstances of each talk show, the publicity appearances are even more controlled by Cohen than I had assumed.

I also remarked that it is difficult to judge the degree to which the film manipulated the scenes of Borat’s encounters with real people. Especially in terms of editing and sound techniques, there was clearly much opportunity for this manipulation. The same Variety story goes on to say, “Much of the script had to be altered depending on how situations unravel. This means the writers ultimately end up producing the equivalent of multiple scripts, much of which ends up on the cutting room floor.” I’m not sure how chunks of scripts can end up on the cutting-room floor, but the point is that the filmmakers were carefully stitching the “documentary” scenes together on the script level and presumably would do so through stylistic means as well.

David writes:

Back to the Hotel

The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, blogged here) has acquired yet another English-language title: Hotel Avanti. It made it to #93 on Variety‘s list of the world’s 100 top-grossing films, with $51 million box office in Japan and none yet recorded overseas.

Speaking of Variety‘s list, the highest-grossing non-English language item turns out to be Bong Joon-ho’s Korean hit The Host (#59 at $84 million), due out in the US any month now. Only ten non-English-speaking films made the top 100, and of those, three were European (including Volver) but all the rest were Asian: Chinese (Fearless), Korean (The Host and King and Clown), and Japanese (Tales from Earthsea, Umizaru 2 Limit of Love, Hotel Avanti, and Japan Sinks–no rude remarks, please).

The entire list is in the 15-21 January hard copy of Variety, p. 15, but evidently it isn’t yet available on the paper’s site.

More on Johnnie To

In an earlier blog I praised Johnnie To as a director who shot and cut PTU smoothly and crisply. I waited through the fall, hoping somehow to see To’s latest, Exiled, on the big screen at one festival or another. No such luck. So last night I broke down and watched the DVD. Making full use of the widescreen format, To shows that classic technique can be at once rigorous and imaginative.

Exiled was more visually engaging than any US film I can recall last year, including Miami Vice. It immediately became my Best Film of 2006 That I Saw in 2007. (Runner-up: Children of Men.) I visited Milkyway while the film was being shot, and I hope to blog about the result in a future entry.

At Large on the Internets

On this very site, I’ve posted a new essay on action movies.

Annie Frisbie interviewed me for the Zoom-In podcast here. Annie is also blogging/reviewing Sundance films here.

Fox Independent visited Madison and posted videos on its site. The setup and the interview with filmmaker and teacher Erik Gunneson are here. An interview with me is here.

An appetite for artifice

Offscreen (Christoffer Boe)

DB here (no, not above):

Catching up with several of the fall’s films, I was struck by how often they played quite self-consciously with the overall shape of their plots. Here are some examples.

Network narratives. This is the label I applied in The Way Hollywood Tells It to those films highlighting several protagonists inhabiting distinct, but intermingling, story lines. In Poetics of Cinema, I have an essay examining the conventions of this format. Several films I saw this fall continued this tradition.

*Bobby used the familiar device of gathering everyone in a single spot–a hotel–within a short time frame and interweaving personal stories with a fateful climax. I thought the film was fairly clumsy, but I was still moved. In 1964 I filmed RFK when he stumped our town for the presidential nomination, and in college, though leaning toward Gene McCarthy I thought Bobby was the only candidate who could beat the Republicans. “Dump the Hump!” (Hubert Humphrey) was the rallying cry.) His assassination, during the same year Martin Luther King was killed, was very traumatic to young idealists. Estevez’s film becomes most powerful, I think, by simply replaying footage and speeches, reminding us that there was once a rich politician who talked incessantly about helping the poor. Just as Stone’s JFK positioned Jack as the man who could have averted the Vietnam War, Bobby makes RFK the anti-Bush.

*Fast Food Nation was for me a more satisfying use of the network narrative format. Here the time scheme is more diffuse because Linklater is tracing a large-scale process, the burger from the hoof to the Happy Meal. By starting with the middle-management character (Greg Kinnear) and then easing us into the harsh working life facing Mexican illegals, the film builds sympathy for the immigrants. Gradually, the illegals’ stories take over, and the social conscience of one of the burger chain’s teenage workers is ignited.

The plotting makes some thoughtful moves. A more literal approach would have shown us the meat-processing plant’s killing floor early, as part of the step-by-step process. But here the shocking material isn’t presented until the very climax of the film, as the fate to which the immigrant working woman must submit. Likewise, the film drops the Kinnear character about halfway through, a ploy that conceals from us how he’ll act on his new knowledge. Will he blow the whistle on the plant, and endanger his job? A European film might have left his whole line of action open, but Linklater adheres to the tendency of American films to resolve a plotline one way or another. He does it, however, in an epilogue which leaves us with a sharpened sense of the acute problems of the system.

*The Uchoten Hotel (aka Suite Dreams, Japan, 2006). In the vein of Tampopo and Shall We Dance?, Mitani Koki offers gentle humor mixed with satiric social observation. Confusion reigns at the Avanti Hotel on New Year’s Eve, as a philandering professor, a corrupt Senator, low-end showbiz types, and the hotel staff become embroiled in one another’s lives. Lively long takes display subtle staging, and there’s a ventriloquist’s duck. A tribute to Grand Hotel, Billy Wilder, and Jacques Tati, this good-hearted survey of human aspirations was the most uncynical movie I saw all year.

Many critics seem to feel that the network format is tired out. At indieWire, Nick Schager calls for “a moratorium on second-rate Nashville-style ensemble pieces that seem increasingly to be the province of every Tom, Dick, and Emilio.” The key words are “second-rate”: Like any storytelling pattern, the network option can be used well or badly. Linklater and Mitani use it with flair.

The point I’d stress is that although the network model can claim to be a realistic device (in our world, our projects commingle), it’s almost always presented through a series of conventions–traffic accidents, people brushing past each other, narration that holds back information about the characters’ relationships, and so on. We recognize these as part of the artifice in this tradition of storytelling.

Broken Timelines. During his DVD commentary for Basic, John McTiernan uses this phrase to explain the film’s flashbacks and replays. In the terms we use in Film Art, the linear story action is scrambled or rearranged in the plot that that the film presents to us.

Screenwriters used to urge novices to avoid breaking up the timeline, but in the 1940s through the mid-1950s, films began to play around with story order. Citizen Kane (1941) probably encouraged the flashback form, as did film noir’s emphasis on mystery and crime detection. Siodmak’s fine The Killers offers a prototype. (I discuss its plot maneuvers in Narration in the Fiction Film.)

We don’t lack for flashbacks in contemporary films, but things are getting complicated. Today a film may open with a quite mystifying sequence, before backtracking to acquaint us with the situation. In itself, this isn’t very unusual, since flashback-based films have often opened at a point of crisis and then taken us back to the beginning of the action. The Big Clock and Written on the Wind are instances. The new wrinkle is to actually replay the opening situation or just the images from it in a new context.

*The Fountain by Darren Aronofsky offers one example. Using three time layers, it can keep replaying the opening portions in ways that recontextualize the material we saw at first. In its out-of-this-world realm, as well as its suggestion that the story is in some sense being written as we see it, it reminded me of Slaughterhouse-Five (1972)–another indication that these innovations aren’t brand new.

*Another instance: The opening image of Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), with a bloody Nicolas Bro in close-up advancing to the camera, gets explained only at the grisly climax.

*The recontextualizing replay isn’t an avant-garde device. Tony Scott’s well-done thriller Déjà Vu uses it in the context of a time-travel plot. It replays the opening sequence in a way that suggests both a branching or alternative future and a deeper understanding of what we saw initially. A similar pattern is found in Flags of Our Fathers, in which we reinterpret the opening differently now that we know the characters more fully. I suppose that Pulp Fiction‘s opening became a powerful influence on this formal choice.

When an action is replayed, it can be shown from different characters’ perspectives. Again, this was explored a lot in the 1940s, as in Mildred Pierce (a replay of the opening) and Crossfire (a replay of the crucial incident). The device is on display in The Killing and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance as well. Kurosawa’s Rashomon made the technique more ambiguous, by not confirming which version of events is accurate. The same idea guides the money exchange in Tarantino’s Jackie Brown, which we discuss in the new edition of Film Art.

*The broken timeline of Three Burials of Melquiades Estrada uses multiple points of attachment mildly, in the murder scene. The replays are more significant and fragmentary in The Prestige. More films in this vein are in preparation, including Vantage Point, which shows an assassination attempt on a US president as seen from five characters’ points of view, “unfolding in 15-minute increments.”

Companion films. Back in the 1960s, Fox announced that it wanted to make Tora! Tora! Tora! with two directors, one Japanese and one American. My friends and I indulged in a game: Whom should they pick? (I favored Ozu and Samuel Fuller.) As you probably know, Kurosawa’s collaboration came to naught (though he did shoot some footage, discussed by Richard Fleischer in his book and his DVD commentary on the film). Fukasaku Kinji and evidently some other directors contributed to the Japan-based footage.

Now, instead of one film with two directors, Clint Eastwood gave us two complementary films from a single hand. I haven’t yet seen Letters from Iwo Jima, but the very idea of showing the same battle from opposite sides in two movies acknowledges a level of artifice.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The French got here first, I think. Marguerite Duras made a companion film to her mesmerizing India Song (on right) called Son nom de Venise dans Calcutta desert. Son nom had exactly the same soundtrack as India Song but a wholly different image track–only landscapes around the site of action, empty (as I recall) of all human presence. A comparable instance is the alternate-worlds pairing by Alain Resnais, Smoking/ No Smoking, adapted from a cylce of Alan Ayckbourn plays.

The companion-film concept seems to be expanding. Red Road, directed by Andrea Arnold, is launching a series of films to based in Scotland and all featuring the same group of characters, but filmed by different directors. The characters are conceived by filmmakers Lone Scherfig (Wilbur Wants to Kill Himself) and Anders Thomas Jensen (Brothers). In a way, a sort of episodic-television idea applied to feature films.

What’s behind this? Why are today’s movies using such self-conscious artifice in their plotting? Is form the new content, the way gray is the new black?

Complex storytelling can be found in a lot of other media today. It’s common to point to Hill Street Blues and later TV shows as reinforcing tendencies toward network narratives in film. Jason Mittell discusses the tendency in Velvet Light Trap no. 58. His article “Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television” (available here), makes the case that shows like 24, Arrested Development, Buffy, Malcolm in the Middle, and so on have offered viewers ways “to be actively engaged in the story and successfully surprised through the storytelling’s manipulations”–a good way to describe some of the strategies I’ve been sketching.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In graphic novels and comic art we’re seeing the same tendencies. Daniel Clowes and Chris Ware manipulate time and space in virtuoso ways, as does the highly formalized movement known as OuBaPo. You can check out an American version of OuBaPo in Matt Madden’s 99 Ways to Tell a Story.

In Everything Bad Is Good for You, Steven Johnson argues that people are just getting smarter, and so popular culture is pitched at a more sophisticated level. But quite complex artifice can be found in mass media of earlier eras. As I mention in The Way, we can find backward-told stories in popular fiction long before Memento, and Grand Hotel is an early prototype of the network narrative. Our ancestors weren’t necessarily dumber than we are, and popular art has long harbored experimental impulses.

I’d hypothesize some other causes. Regardless of IQ, more members of the audience have been to college today than in early eras. More of the creators have studied modern art and literature and are ready to borrow experimental devices they’ve encountered in other media. This process has a familiar ring. American filmmaking has often renewed itself by absorbing all manner of experiment, from German Expressionism (for 1930s horror films) to serial music (for 1950s psychological dramas). Usually, I feel compelled to add, the experimental devices are absorbed into existing forms, like classical script structure, genres, or stylistic principles.

I suspect as well that the new genre hierarchy that emerged in the last couple of decades cranked up the artifice level. The rise of science fiction, mystery, fantasy, horror, and comic-book movies probably encouraged clever juggling with story order, point of view, and states of knowledge. So did the rise of indie cinema, which needs narrative innovation to set itself apart from the mainstream. Again, Pulp Fiction fuses the two strands: an indie neo-noir that attracted attention through its bold manipulation of story/ plot relations.

At the same time, filmmakers in other countries have been eager to push the boundaries. Many of the broken-timeline devices have their sources in art cinema of the 1950s and 1960s. Younger European directors like Boe and Tom Tykwer (Run Lola Run) have revived this adventurous attitude toward storytelling, putting them somewhat in sync with American directors. Asian experimentalists like Wong Kar-wai and Hou Hsiao-hsien continue to exercise a comparable influence.

We need to think more about where this impulse toward innovation comes from and how it shows itself, but it seems likely that the flourishing trade in self-conscious storytelling will be with us for some time yet. Hollywood cinema has long been self-consciously, almost fussily formal, and it has a vast appetite for artifice.

I Wrote a Book, But…; or, What Did the Professor Forget?

My 1988 book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is available again, I’m happy to report. There’s a little backstory, probably of interest only to those who follow the zigzags of academic publishing.

Around 1990 the British Film Institute declared the book out of print. The US copublisher, Princeton University Press, agreed to keep it in print under two conditions.

First, I would have to pay for the cleaning of the preprint material (the sheets of plastic on which the master copies of the pages were printed). Cost: $1000. Second, I would receive no royalties. I agreed to the terms, since I wanted to have this book, for all its faults, available.

So for about a decade, the book was still out there. I enjoyed the anecdotal value of getting royalty statements reading: Your royalty payment is $000.00. Still, all those decimal places sort of rubbed it in. Wouldn’t $0 have been enough?

As Ozu’s centenary approached in 2003, I contacted Princeton to alert them. Maybe there’d be a bump of interest in Ozu, and they might want to do another printing. But the Press replied that, um, they had some months before declared their edition out of print.

Publishers have a habit of not telling authors about decisions like this. There’s no fun way to announce that a book is orphaned, or maybe slain. Then too there’s the somewhat awkward matter of returning a piece of intellectual property that might become an asset some day. Anyhow, Jerry Bruckheimer wasn’t likely to pick up the movie rights to Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, and so after regaining copyright control, I took the book on the road.

No surprise: Other publishers were not crazy about reprinting a big fat book with lots of pictures, published fifteen years before and probably bought by every soul who might ever want a copy. I’d hoped that a book on very likely the greatest film director who ever lived might be worth keeping around. But no, alas.

Every month or so, as the Ozu touring program roamed greater North America in 2003 and 2004, a fan would email asking me to sell a copy of the book. Web booksellers were demanding up to $600. The thought of selling one to a book dealer at a jacked-up price, perhaps with a signature affixed, did cross my mind, but I had only two copies of my own.

Eventually I learned of the publishing program launched by the University of Michigan Center for Japanese Studies. The Center had begun posting out-of-print books on Japanese cinema online. I contacted Markus Nornes, who generously sponsored and oversaw the project.

I learn from a correspondent that the book is now available in pdf form online.

Now you can read the book, and can even buy a print-on-demand copy if you want. (I look forward to the $000.00 checks from Ann Arbor.) The downside: The 500-plus pictures range from tolerable to terrible. I also planned to write an introduction with updates and corrections, and I still hope to do that. There’s even talk about replacing some stills, perhaps with color frames.

So if you’re interested in Ozu, Japanese film history, or the poetics of cinema, you might want to check this out. Of course you can instead crack your piggy bank and order the single copy of the original I’ve found on what our President calls the Internets.

If I were in an Ozu film, I’d probably now emit a sigh mixing satisfaction and resignation. Then I’d reach for a beer. Or at least an orange drink. No, a beer.

Update, November 10: I’d thought that print-on-demand copies would be available, but Carsten Czarnecki points out that the Center site doesn’t seem to indicate that. I’ll check further.

Update #2, same day: Our keen-eyed web tsarina Meg has found still other copies of the original book available, at prices starting at $118.95, here. Please remit 10 % finder’s fee to her.

Update #3, November 11: Markus tells me that we hope eventually to offer print-on-demand copies, but the technology doesn’t yet meet the Center’s standards. Good! We want nice-looking images, when we can finally get ’em.