Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Stuck inside these four walls: Chamber cinema for a plague year

The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972).

Privacy is the seat of Contemplation, though sometimes made the recluse of Tentation… Be you in your Chambers or priuate Closets; be you retired from the eyes of men; thinke how the eyes of God are on you. Doe not say, the walls encompasse mee, darknesse o’re-shadowes mee, the Curtaine of night secures me… doe nothing priuately, which you would not doe publickly. There is no retire from the eyes of God.

Richard Brathwaite, The English Gentlewoman (1631)

DB here:

We’re in the midst of a wondrous national experiment: What will Americans do without sports? Movies come to fill the void, and websites teem with recommendations for lockdown viewing. Among them are movies about pandemics, about personal relationships, and of course about all those vistas, urban or rural, that we can no longer visit in person. (“Craving Wide Open Spaces? Watch a Western.”)

Cinema loves to span spaces. Filmmakers have long celebrated the medium’s power to take us anywhere. So it’s natural, in a time of enforced hermitage, for people to long for Westerns, sword and sandal epics, and other genres that evoke grandeur.

But we’re now forced to pay more attention to more scaled-down surroundings. We’re scrutinizing our rooms and corridors and closets. We’re scrubbing the surfaces we bustle past every day. This new alertness to our immediate surroundings may sensitize us to a kind of cinema turned resolutely inward.

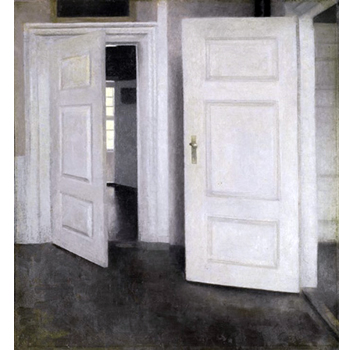

Long ago, when I was writing a book on Carl Dreyer, I was struck by a cross-media tradition that explored what you could express through purified interiors. I called it “chamber art.” In Western painting you can trace it back to Dutch genre works (supremely, Vermeer). It persisted through centuries, notably in Dreyer’s countryman Vilhelm Hammershøi (below).

Plays were often set in single rooms, of course, but the confinement was made especially salient by Strindberg, who even designed an intimate auditorium. For cinema, the major development was the Kammerspielfilm, as exemplified in Hintertreppe (1921), Scherben (1921), Sylvester (1924), and other silent German classics. Kristin and I talk about this trend here and here.

In the book I argued that Dreyer developed a “chamber cinema,” in piecemeal form, in his first features before eventually committing to it in Mikael (1924) and The Master of the House (1925). Two People (1945) is the purest case in the Dreyer oeuvre: A couple faces a crisis in their marriage over the course of a few hours in their apartment. (Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem available with English subtitles.) But you can see, thanks to Criterion, how spatial dynamics formed a powerful premise of his later masterpieces Vampyr (1932), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1955), and Gertrud (1964).

Dreyer wasn’t alone. Ozu tried out the format in That Night’s Wife (1930), swaddling a husband, wife, child, and detective in a clutter of dripping laundry and American movie posters.

Bergman exploited the premise too, in films like Brink of Life (1958), Waiting Women (1952), his 1961-1963 trilogy, and Persona (1966). (All can be streamed on Criterion.)

Chamber cinema became an important, if rare expressive option for many filmmaking traditions. Writers and directors set themselves a crisp problem–how to tell a story under such constraints?

The challenge is finding “infinite riches in a little room.” How? Well, you can exploit the spatial restrictiveness by confining us to what the inhabitants of the space know. Limiting story information can build curiosity, suspense, and surprise. You can also create a kind of mundane superrealism that charges everyday objects with new force.

On the other hand, you need to maintain variety by strategies of drama and stylistic handling. Chamber cinema–wherever it turns up–offers some unique filmic effects, and maybe sheltering in place is a good time to sample it.

Herewith a by no means comprehensive list of some interesting cinematic chamber pieces. For each title, I link to streaming services supplying it.

Bottles of different sizes

From David Koepp I learned that screenwriters call confined-space movies “bottle” plots. There’s a tacit rule: The audience understands that by and large the action won’t stray from a single defined interior. In a commentary track for the “Blowback” episode of the (excellent) TV show Justified, Graham Yost and Ben Cavell discuss how TV series plan an occasional bottle episode, and not just because it affords dramatic concentration. It can save time and money in production.

Usually the bottle consists of more than a single room. The classic Kammerspielfilms roam a bit within a household and sometimes stray outdoors. But their manner of shooting provides a variety of angles that suggest continuing confinement. Dreyer went further in The Master of the House. He built a more or less functioning apartment as the set, then installed wild walls that let him flank the action from any side. Then editing could provide a sense of wraparound space.

The variations in camera setups throughout the film are extraordinary. Dreyer would create more radically fragmentary chamber spaces in La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), while his later films would use solemn, arcing camera movements to achieve a smoother immersive effect. (For more on Dreyer’s unique spatial experimentation, here’s a link to my Criterion contribution on Master of the House. I talk about the tricks Dreyer plays with chamber space in Vampyr in an “Observations” supplement on the Criterion Channel.)

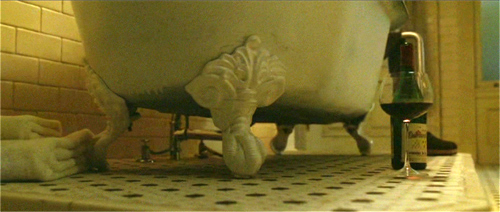

Likewise, Koepp’s screenplay for Panic Room allows David Fincher to move 360 degrees through several areas of a Manhattan brownstone. The film also offers a fine example of how our awareness of domestic details gets sharpened by a creeping camera.

Trust Fincher to find sinister possibilities in a dripping bathtub leg and a kitchen island.

Confined to quarters

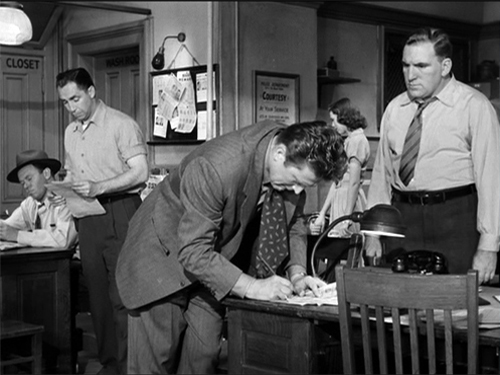

Detective Story (1951).

Many chamber movies are based on plays, as you’d expect. Unlike most adaptations, though, they don’t try to “ventilate” the play by expanding the field of action. Or rather, as André Bazin pointed out, the expansion is itself fairly rigorous. They don’t go as far afield as they might.

Bazin praised Cocteau’s 1948 version of his play Les parents terribles (aka “The Storm Within”) for opening up the stage version only a little, expanding beyond a single room to encompass other areas of the apartment. This retained the claustrophobia, and the sense of theatrical artifice, but it spread action out in a way that suited cinema’s urge to push beyond the frame. The freedom of staging and camera placement is thoroughly “cinematic” within the “theatrical” premise.

Depending on how you count, Hitchcock expanded things a bit in his adaptation of Dial M for Murder. Apart from cutting away to Tony at his club, Hitchcock moved beyond the parlor to the adjacent bedroom, the building’s entryway, and the terrace.

An earlier entry on this site talks about how 3D let Sir Alfred give an ominous accent to props: a particularly large pair of scissors, and a more minor item like the bedside clock.

Hitchcock gave us a parlor and a hallway in Rope (1948), but when Brandon flourishes the murder weapon, the framing audaciously reminds us that we aren’t allowed to go into the kitchen.

Bazin did not wholly admire William Wyler’s Detective Story (1951), despite its skill in editing and performances; he found it too obedient to a mediocre play. True, the film doesn’t creatively transform its source to the degree that Wyler’s earlier adaptation of The Little Foxes (1941) did; Bazin wrote a penetrating analysis of that film’s remarkable turning point. Detective Story is more obedient to the classic unities, confining nearly all of the action to the precinct station. Although I don’t think Wyler ever shows the missing fourth wall, he creates a dazzling array of spatial variants by layering and spreading out zones of the room. In his prime, the man could stage anything fluently.

As Bazin puts it: “One has to admire the unequaled mastery of the mise-en-scène, the extraordinary exactness of its details, the dexterity with which Wyler interweaves the secondary story lines into the main action, sustaining and stressing each without ever losing the thread.”

Some films are even more constrained. 12 Angry Men (1957), adapted from a teleplay, is a famous example. Once the jury leaves the courtroom, the bulk of the film drills down on their deliberation. Again, the director wrings stylistic variations out of the situation; Lumet claims he systematically ran across a spectrum of lens lengths as the drama developed.

But you don’t need a theatrical alibi to draw tight boundaries around the action. Rear Window (1954), adapted from a fairly daring Cornell Woolrich short story, is as rigorous an instance of chamber cinema as Rope. Here Hitchcock firmly anchors us in an apartment, but he uses optical POV to “open out” the private space.

With all its apertures the courtyard view becomes a sinister/comic/melancholy Advent calendar.

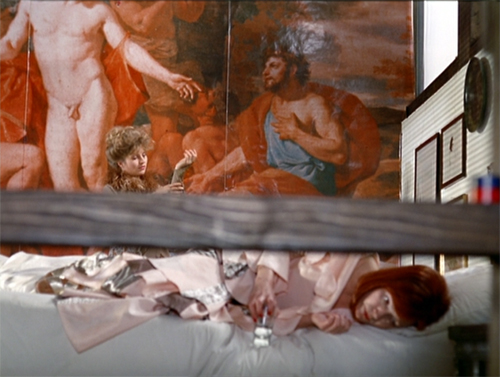

Fassbinder’s Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) denies us this wide vantage point on the outside world. This space seems almost completely enclosed. But Fassbinder finds a remarkable number of ways to vary the set, the camera angles, and the costumes. We’re immersed in the flamboyant flotsam of several women’s lives. The result is a cascade of goofily decadent pictorial splendors.

It’s virtually a convention of these films to include a few shots not tied to the interiors. At the end, we often get a sense of release when finally the characters move outside. That happens in 12 Angry Men, in Panic Room, in Polanski’s Carnage (2011) , and many of my other examples. Without offering too many spoilers, let’s say Room (2015) makes architectural use of this option.

On the road and on the line

Filmmakers have willingly extended the bottle concept to cars. The most famous example is probably Kiarostami’s Ten (2002), which secures each scene in a vehicle and mixes and matches the passengers across episodes. The strictness of Kiarostami’s camera setups exploit the square video frame and always yield angular shot/reverse shots. They reveal how crisp depth relations can be activated through the passing landscape or in story elements that show up in through the window.

Perhaps Kiarstami’s example inspired Danish-Swedish filmmaker Simon Staho. His Day and Night (2004) traces a man visiting key people on the last day of his life, and we are stuck obstinately in the car throughout. This provides some nifty restriction, most radically when we have to peer at action taking place outside.

Staho’s Bang Bang Orangutang (2005), a portrait of a seething racist, takes up the same premise but isn’t quite so rigorous. We do get out a bit, but the camera stays pretty close to the car. I discuss Staho’s films a little in a very old entry.

Like autos, telephones provide a nice motivation for the bottle, as Lucille Fletcher discovered when she wrote the perennial radio hit, “Sorry, Wrong Number.” The plot consists of a series of calls placed by the bedridden woman, who overhears a murder plot. The film wasn’t quite so stringently limited, but the effect is of the protagonist at the center of several crisscrossed intrigues.

A purer case is the Rossellini film Una voce umana (1948), in which a desperate woman frantically talks with her lover. It relies on intense close-ups of its one player, Anna Magnani.

It’s an adaptation of a Cocteau play, which Poulenc turned into a one-act opera. In all, the duration of the story action is the same as the running time.

I wish Larry Cohen’s Phone Booth displayed a similarly obsessive concentration, but we do have the Danish thriller The Guilty, where a police dispatcher gets involved in more than one ongoing crime. We enjoyed seeing it at the 2018 Wisconsin Film Festival.

And of course car and phone can be combined, as they are in Locke (2013)–another play adaptation. Tom Hardy plays a spookily calm businessman driving to a deal while taking calls from his family and his distraught mistress. Those characters remain voices on the line while he tries to contend with the pressures of his mistakes.

House arrest, arresting houses

Sometimes you must embrace the chamber aesthetic. In 2010 the fine Iranian director Jafar Panahi was forbidden to make films and subjected to house arrest. Yet he continued to produce–well, what? This Is Not a Film (2012) was shot partially on a cellphone within (mostly) his apartment.

Wittily, he tapes out a chamber space within his apartment. Then he reads a script to indicate how absent actors could play it and how an imaginary camera could shoot it.

But his imaginary film still isn’t an actual film, so he hasn’t violated the ban. So perhaps what we have is rather a memoir, or a diary, or a home video? Panahi’s virtual film (that isn’t a film) exists within another film that isn’t a film. Yet it played festivals and circulates on disc and streaming. The absurdity, at once touching and pointed, suggests that through playful imagination, the artist can challenge censorship.

Panahi slyly pushed against the boundaries again with Closed Curtain (2013, above). Shot in his beach house, it strays occasionally outside. Next came Taxi (2015), in which Panahi took up the auto-enclosed chamber movie, with largely comic results.

More recently, he has somehow managed to make a more orthodox film, 3 Faces (2018), which considers the situation of people in a remote village.

The chamber-based premise needn’t furnish a whole movie. As in Room, Kurosawa’s High and Low (1963) is tightly concentrated in its first half. We are in two enclosures, a house and a train. The film then bursts out into a rushed, wide-ranging investigation. Large-scale or less, the chamber strategy remains a potent cinematic force.

They say that the last creatures to discover water will be fish. We move through our world taking our niche for granted. Cinema, like the other arts, can refocus our attention on weight and pattern, texture and stubborn objecthood. We can find rich rewards in glimpses, partial views, and little details. Chamber art has an intimacy that’s at once cozy and discomfiting. Seeing familiar things in intensely circumscribed ways can lift up our senses.

So take a break from the crisis and enjoy some art. But return to the world knowing that for Americans this catastrophe is the result of forty years of monstrous, gleeful Republican dismantling of our civil society. Rebuilding such a society will require the elimination of that party, and the career criminal at its head, as a political force. This pandemic must not become our Reichstag fire.

Yeah, I went there.

Thanks to the John Bennett, Pauline Lampert, Lei Lin, Thomas McPherson, Dillon Mitchell, Erica Moulton, Nathan Mulder, Kat Pan, Will Quade, Lance St. Laurent, Anthony Twaurog, David Vanden Bossche, and Zach Zahos. They’re students in my seminar, and they suggested many titles for this blog entry.

Bazin’s comments on Detective Story come in his 1952 Cannes reportage, published as items 1031-1033, and as a review (item 1180), in Écrits complets vol. I, ed. Hervé Joubert-Laurencin (Paris: Macula, 2018), pp. 918-922, 1059. My quotation comes come from the review, where he does grant that Wyler is the Hollywood filmmaker “who knows his craft best. . . . the master of the psychological film.”

The tableau style of the 1910s probably helped shift Dreyer toward the chamber model, which he learned to modify through editing. I discuss Dreyer’s relation to that style in “The Dreyer Generation” on the Danish Film Institute website. Also related is the web essay, “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic.”

Some other examples could be mentioned, but I didn’t find them on streaming services in the US. It would be nifty if you could see the tricks with chamber space in Dangerous Corner (1934); fortunately it plays fairly often on TCM. There’s also Duvivier’s Marie-Octobre (1959), a tense drama about the reunion of old partisans.

I especially like the 1983 Iranian film, The Key, directed by Ebrahim Forouzesh and scripted by Kiarostami. It’s a charming, nearly wordless story of how a little boy tries to manage household crises when Mother is away. It has the gripping suspense that is characteristic of much Iranian cinema, and the boy emerges as resourceful and heroic (though kind of messy). Kids would like it, I think.

Also, I’ve neglected Asian instances. Maybe I’ll revisit this topic after a while.

P.S. 1 April 2020: Thanks to Casper Tybjerg, outstanding Dreyer scholar, for corrections about the nationality of The Guilty and the Staho films.

Gertrud (1964).

Ozu the compassionate satirist: THE FLAVOR OF GREEN TEA OVER RICE on Criterion Blu-ray

DB here:

Another bountiful disc release from Criterion: Ozu’s 1952 classic in a 4K digital restoration, with newly translated subtitles. It comes with an enlightening essay by Junji Yoshida and Daniel Raim’s ingratiating documentary on Ozu’s collaboration with his screenwriter Kogo Noda. I contributed a video essay on the film. The most wonderful bonus is Ozu’s 1937 feature What Did the Lady Forget?, which has fascinating affinities with the later movie.

What did which lady forget?

I’ve long been a fan of What Did the Lady Forget? It’s a quasi-screwball comedy treating the clash of the sexes and the generations. As is typical for Ozu, it starts light, abetted by a languid guitar-and-banjo soundtrack, before sidling into graver moments.

In my commentary I touch on its social satire. As the Shochiku studio began making more films about prosperous families, Ozu moved away from the working-class and salaryman milieus he had explored in many masterpieces of the 1930s. I argue in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema that this film’s comic treatment of the professional class looks forward to what he’ll offer in Equinox Flower (1958) and other postwar films.

A married couple hosts a visit from their sashaying, cigarette-smoking niece, a moga (modern girl) who turns out to be not quite as tough as she thinks. While exploring the city’s nightlife (and occasionally brandishing a fencing foil), Setsuko exposes the tensions in the apparently easygoing marriage. The comedy drifts into moments of Ozuian pathos and melancholy–a chastened Setsuko has to leave Tokyo–but the film ends on a light note.

Stylistic finesse is on display throughout. The framings are dazzlingly inventive, the perspectives are steep, and we’re given those quietly permutational “establishing shots” that introduce scenes in Setsuko’s room.

The weird graphic matches in the two boys’ “hit the spot” game could not have been devised by anybody else.

I just love this stuff. There’s so much here, how can this movie be only 70 minutes long?

What Did the Lady Forget? contains a disturbing burst of domestic violence. But the husband soon regrets it, and Ozu and his screenwriter Akira Fushimi develop the crisis in way that keeps shifting our judgment about what characters learn from the incident.

A distressed marriage

In a parallel situation in the “remake,” The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, the husband remains calm in the face of his wife’s criticism. Mokichi is far from a paragon (he’s a phlegmatic workaholic, he’s out of touch with young folks and urban culture), but at home he’s quiet and apologetic. When Taeko complains about his table manners, he tries gently to explain why he slurps his rice.

Daniel Raim’s short on the Ozu-Noda collaboration concentrates on the planning of An Autumn Afternoon (1962), well-documented in Donald Richie’s Ozu. But we also have some records of their work routine on Green Tea. Ozu kept no fewer than five notebooks that year, sometimes recording the same event in two or more.

On 20 January, he notes that he and Noda are “bringing back a problematic script.” That’s because the original Flavor of Green Tea over Rice was refused by censors in 1940. In early 1952 Ozu was in the process of moving to Kamakura, so the two men’s collaboration took place in inns, Noda’s home, and the studio. One notebook logs Ozu’s production schedule, while others are more personal.

Ozu’s films from the 1950s on were typically planned in the winter, shot in spring and summer, and premiered in the fall, as if he were determined to document each year’s good weather. Ozu and Noda began writing Green Tea on 29 February and finished on 1 April, sometimes preparing three scenes a day. After consulting with Shiro Kido, the studio head, they revised the script. Ozu’s efficiency in planning every scene and sketching every shot allowed production to proceed fast. The crew began shooting on 7 June, in an office set. They finished on 13 July (“Finally, rest!”) and The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice premiered on 1 October.

Pretty intensive work. But you wouldn’t know it from the companion notebooks. Among chronicles of naps, baths, social gatherings, changing weather, baseball games, and bar-hopping with friends, how did they get any work done? Above all there’s Ozu’s careful record of his alcohol intake (“drank until 2 AM”). A stomach ache makes him think he might have an ulcer. “I must resolve not to drink too much. And stick to it!” Today we would call him a high-functioning alcoholic. “With the whisky I drank this morning and the shumai I brought back from Tokoen, I wasn’t at all hungry tonight.”

As in his films, the everyday and the unusual get equal treatment. While staying at one inn, he calmly observes the arrival of a woman’s baseball team. And he remained a cinephile. He’s happy to interrupt an evening of dining and drinking to go see William Dieterle’s September Affair (1950).

The film that resulted, I suggest in the supplement, modulates between satire and a generous comedy that gives the main characters, no matter their failings, moments of warmth and dignity. With a light hand Ozu summons up narrative parallels, and he spotlights the split between men’s culture and women’s culture. A troubled marriage is given due weight, but it’s saved by graciousness, as when (above) Mokichi rescues Taeko’s sleeve from the water in the sink.

Ozu carries the humor down to the fine grain of technique, teaching us to play a private cinematic game in which the characters participate all unawares. The Criterion creative team has ingeniously used split screens to help me show the evolution of stylistic patterns across the film. Shedding my Mr. Rogers sweater for a sport coat, I try to crack the mystery of those eerie tracking shots. Like the situations and the dialogue, these barely moving images ought to make you smile.

Thanks to producer Elizabeth Pauker and her colleagues at Criterion, especially Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson and James Runde here at UW–Madison.

Ozu’s diaries of shooting The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice are available, with helpful annotations, in Yasujiro Ozu: Carnets 1933-1963, trans. Josiane Pinon-Kawataké (Editions ALIVE, 1996), 267-318.

My book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, is available for free here. Color pictures and everything! But be patient; it’s big and takes a while to download. There are many entries on Ozu and Donald Richie elsewhere on this site.

What Did the Lady Forget? (1937).

How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on the Criterion Channel

Street of Shame (1956).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Kenji Mizoguchi

DB here:

So much of contemporary film and TV takes pictorial space for granted. Yes, The Avengers: Endgame stuffs its frame with, well, stuff, but you’re seldom given time to see everything. Even in films not so dominated by CGI, if the the actors’ faces and gestures come across and you can hear the line readings, that’s pretty much enough. Most of the rest is there to fill out the very wide frame.

“Wait,” I hear someone saying. “Thanks to Steadicam, directors use camera movements to sweep through space all the time.” Yeah, that’s just my point: They sweep through. We’re following characters’ backs or fronts, not exploring space as such. Very seldom do we get a chance to probe what’s revealed, except in carefully wrought movies like Sunset (which tease you into trying to discern what’s not even in focus).

Moreover, today the pace of the editing is so fast, even in an “intimate” movie like Booksmart, that the actors’ faces dominate everything. For fifty years many directors have been “shooting for the box,” shoving their actors into close-ups that will read on TV, now on computers and smartphones. Like the endlessly moving camera, the big heads and the quick cuts refresh the image often enough to hold our interest in a distracting environment.

Granted, most filmmakers now supplement their fast-cut, rapid-pan close-ups with an occasional landscape shot that can look pretty, in a calendar-image sort of way. Overhead shots, now facilitated by drones, swoop us through the towering corridors of The City or across a swath of forest in a way that is undeniably impressive. This convention doesn’t count, for me, as pictorial intelligence unless somebody like Tony Scott does something, however nutty, with it.

I’m not against these stylistic choices per se; every style is valid if it’s pursued with imagination, rigor, and delicacy. Nor am I suggesting that the other extreme, so-called slow cinema, is inherently more virtuous. Long unmoving takes can be paralyzingly dull. Ozu made fast cutting just as “contemplative” as Hou or Tarr, because he knew how to design pictures.

It’s just that the norms of intensified continuity and the “free camera” have overwhelmingly dominated current practice. It’s worth remembering other ways moving pictures can be. One way to do that is to revisit film history, and the work of Mizoguchi Kenji is an ideal place to start.

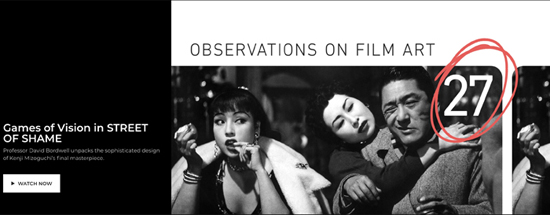

His Street of Shame (1956) is the subject of this month’s Observations entry on the Criterion Channel. In it, I invite you to join me in attending a master class in staging.

The theme is Mizoguchi’s perennial one, that of the ways in which women succumb to or resist their oppression in a patriarchal society. We’re in the Dreamland brothel, where five–eventually, six–women are working at the very moment the government debates eliminating prostitution. Mizoguchi shows how they both cooperate and compete, trying to quit, deploying different strategies for managing their clients, and just getting by. It’s all done through what Mizoguchi called the “hypnotic power” of carefully choreographed images.

A personal note

In a way, Mizoguchi made me a film teacher.

During the week of 25 September 1969, what could you have have seen in Manhattan? I Am Curious: Yellow, La Chinoise, Closely Watched Trains, Miracle in Milan, Hell’s Angels ’69, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Midnight Cowboy, The Killing of Sister George, De Sade, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, One Second in Montreal, <—->, Take the Money and Run, Alice’s Restaurant, Medium Cool, In the Year of the Pig, Easy Rider, Putney Swope, and programs of Kubelka and Jack Smith movies. There were many double bills on offer: The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, Yellow Submarine and The Gold Rush, King Kong and The Lady Vanishes, Seven Samurai and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, Monterey Pop and Don’t Look Back, The Deadly Affair and Funeral in Berlin, Little Sister and Alice in Acidland, Lonesome Cowboys and Flesh.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

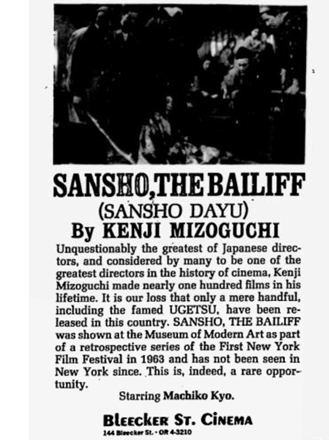

In the city for only a few hours, I didn’t go to any of those shows. There was yet another double bill at the Bleecker but I could catch only one title: not Lola Montès (I would see that in Paris a year later), but Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff.

As a teenager I had read books about cinema (Welles, Hitchcock) and in college I’d written movie reviews and participated in a film club. Now, newly graduated, I was teaching high school. The only Japanese films I’d seen were the Kurosawa standards our club programmed. Despite planning for a career in high-school teaching, I thought about film most of the time. In the pages of Film Culture and Movie I had read about Mizoguchi.

I came out of Sansho with tears streaming down my cheeks. I heard two young men in the lobby talking about the film. Did they go to NYU or Columbia or some such place? All I know was that they loved Mizoguchi’s long takes, as I did. Somehow, those takes had to be connected to the way the movie hit me. I thought something like: I’d like to study this sort of thing.

I returned to my apartment and began figuring out how to apply to graduate school.

Mizoguchi was still largely unknown, certainly unappreciated. The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing Sansho until it resurfaced in a later run. Roger Greenspun made up for the neglect with a a gracious note.

“The Bailiff” is a film of breathtaking visual beauty, but the conditions of that beauty also change–from the etheral delicacy of its beginning (before the kidnapping), through the dark masses of the Bailiff’s compound, to the ordered perspectives of Kyoto and the governor’s palace, and finally to the spare symbolic horizons at the end.

In effect, it moves from easy poetry to difficult poetry. Its impulses, which are profound but not transcendental, follow an esthetic program that is also a moral progression, and that emerges, with supreme lucidity, only from the greatest art.

People talked that way then, with good reason.

Choreography all the way down

I didn’t see much Mizoguchi in the years following. There wasn’t much available. (And Ozu was unknown to us.) I did see Ugetsu and Street of Shame, though they didn’t grab me as fast as Sansho had. Fairly soon, though, New Yorker Films and Audio-Brandon made prints of other Mizoguchi titles available. I started using Mizoguchi films in my teaching, and the more I studied them the more I admired them. I was also inspired by critics Robin Wood and Noël Burch, who sought to explain the emotional and cinematic force of this filmmaker.

I began studying Mizoguchi’s films, traveling to Europe to see them all and make frames from prints. Eventually that work would inform my chapter on his staging in Figures Traced in Light. Although there he bested me two falls out of three, I think that discussion made some headway in analyzing his unique visual strategies. I tried to develop those ideas further in an online supplement to that chapter and in the blog entries “Secrets of the Exquisite Image” and “Sleeves.”

More skilfully and subtly than nearly anybody else, Mizoguchi arranges bodies in space to create powerful pictures. Yet his gorgeous shots aren’t just decoration. He never lets the images, elegant as they are, distract from the dramatic issues arising among the characters. The result, I argue, achieves the sort of “hypnotic power” that Mizoguchi claimed to seek.

In Mizoguchi, I suggest, a fairly dense image “becomes a story” as its elements start to mingle and separate out, letting our eye discover (with guidance) a drama as it emerges. A situation precipitates out of a rich mass of material, and the result is an accumulating tension that’s at once dramatic and pictorial. He evidently learned a lot from von Sternberg, but I think this thickening-and-release dynamic of story and style is reminiscent of Hitchcock or Lang as well.

The students were right: Mizoguchi is a master of the long take. The long take, he said, “allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.”

But we shouldn’t think of this technique in the sort of marathon-competition terms people apply to long takes nowadays. (The current example is Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Today’s long takes are often virtuoso traveling shots. While Mizo made wonderful use of camera movement, he knew the power of stillness. He showed that you can just clamp the camera on the tripod (or the crane) and sculpt the action in front of it.

Among Mizoguchians, there are some who find his later films stylistically compromised. Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942; below) and Loves of the Actress Sumako (1947), with their far-off figures and impeccable, “all-over” compositions, merge austerity and density in ways almost inconceivable today.

Given this radical approach, his greater reliance on closer views in the 1950s work can seem a step backward.

But Mizoguchi was a pluralistic director from his earliest days forward. As I try to show in Figures, he fitted his visual design to the needs of a scene, and even the most severe films draw on diverse techniques. Street of Shame shows his endless resourcefulness in enriching three-shots and two-shots and singles. He found choreographic possibilities at every shot scale, with small gestures and glances becoming as important as characters shifting around the set. In the last shot of the last film he made, a single darting eye commands the image and carries the drama.

Given the sustained shot, Mizoguchi fills it and drains it, re-fills it and thins it out and channels it to a climax, all with a graceful, unobtrusive choreography always driven by the emotions pulsing through the scene. I go back constantly to Philippe Demonsablon: “He emits a note so pure that the slightest variation becomes expressive.”

Mizoguchi works in melodrama. Some directors, such as Sirk, take intense situations and amp them up. But Mizoguchi, like Stahl and Preminger, is always banking the fires. His style presents hot emotions in a cool way, betting that detachment and restraint give the emotions a sort of stark purity. If more filmmakers studied his work, who knows what kind of cinema we might have? I hope you have a chance to check in on this entry.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole fine Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts.

Street of Shame is also available on a generous Criterion Eclipse DVD set. Some years back Masters of Cinema series gave us beautiful Blu-ray transfers of many Mizoguchi films. The Street of Shame edition has a fine feature-length audio commentary by Tony Rayns. Alas, the set including the film has apparently gone out of print.

Robin Wood’s influential essay on Mizoguchi is “The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Gatherer,” in Personal Views: Explorations in Film (Gordon Fraser, 1976), 224-248. Noël Burch’s revisionist account of Japanese cinema is To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), where chapter 20 is devoted to Mizoguchi. (The book is available online here.) Roger Greenspun’s review, “‘Bailiff’ Returns,” appeared in the New York Times (17 December 1969), 61.

For more on the place of Japanese directors in film culture, you can try this entry on Kurosawa and this one on Shimizu.

Street of Shame (1956). The sign reads “Cooperative Association Members” and “Confidential Membership.” Thanks to Steve Ridgely for the translation.

Vancouver 2018: Landscapes, real and imagined

Shoplifters (Kore-eda, 2018).

DB here:

We’ve been attending the Vancouver International Film Festival since 2004. (The entries are tagged here.) It’s provided us many of our happiest viewing experiences, and this year is proving just as exciting. In particular, the festival’s long commitment to new films from Asia hasn’t flagged. Thanks to programmers Shelly Kraicer and Maggie Lee there has been plenty to showcase trends in Hong Kong, China, Taiwan, South Korea, and other lands. We won’t, unfortunately, be here for Hong Sangsoo’s Grass, but here are interim reflections on four items that we’ve seen in our first days.

Families, fraught and fragile

Shoplifters.

Girls Always Happy is a quiet but ingratiating first feature from Yang Ming Ming. Mother and daughter are both writers, and they struggle to live together in harmony while hoping for a legacy from Grandfather and for some resolution in their love lives. Yang says that she based the film on her own life, which rings true when you consider the range of emotions that well up. The two women tease each other, insult each other, ravenously devour meals together, shop partly to annoy sales staff, and sometimes burst out in screams. Reconciliations may be temporary but are still heartfelt.

With the two of them jammed together in a hutong, a neighborhood of cramped old ground-floor apartments, their jousts take on an intensity captured by Yang’s exceptionally tight framings and rapid cutting. Yang storyboarded the entire film, which allowed her quite precise control of composition and focus.

The relentless close-ups allow both psychological intimacy and subtle performances, as well as comparison of eating styles. Trips outside—Wu on her scooter or in her lover’s modern apartment, the mother at a hair salon—provide a respite from what’s essentially a series of escalating two-handed combats. The final shot is a lengthy take that carries our heroines forward into their city. Yang explained in the Q & A that after a film full of fast cutting and lots of talk she decided to end with the sort of long take Chinese filmmakers favor. In this context, with a canny use of a bus’s rearview mirror, the shot becomes an exhilarating, floating passage into the Beijing night.

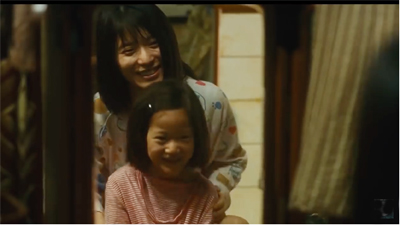

Girls Always Happy came to VIFF garlanded with awards, including prizes from both the Berlinale and the Hong Kong Film Festival. Even more honored was the latest by Kore-eda Hirozaku, The Shoplifters, which won the Palme d’Or at Cannes. It’s another of his family dramas (we’ve discussed Still Walking, I Wish, Like Father, Like Son, Our Little Sister, and After the Storm), but here the notion of family is given an uncanny twist at the end.

Each member, as per Kore-eda’s habit, is given a specific, respectful delineation. There’s the happy-go-lucky Osamu, a day laborer who both coddles the boy Shota and leads him into petty crime. There’s the maternal Nobuyo who works at a dry-cleaning facility and pilfers what she finds in pockets. Twentysomething Aki works at a sex club flashing her breasts and bottom at men crouched behind one-way mirrors. Grandma keeps the group going with her pension, her pachinko-playing, and some secret sources of income. Into this household comes Yuri, an abused child brought home like an abandoned cat.

Like Tsai Ming-liang’s more somber Rain Dogs, this is a film about people on the margins. The kids don’t go to school; Shota teaches Yuri the tricks of shoplifting, while Aki warms to a sex-club client. As in Girls Always Happy, interiors are sharply distinguished from exteriors, but not by close framings and shifting focus. Instead, master shots fill the frame with the detritus of seven people jammed in together. (See shot above.)

In a film so concentrated on characterization, we naturally get the sort of privileged moments that Kore-eda excels in. Osamu pauses in his construction work to stand looking around an unfinished apartment—a modest one, but a home he can never have. The young kids collect cicadas. Aki cradles a lonely punter in her lap. Nobuyo consoles Yuri by comparing the girl’s scars to burns Nobuyo has accumulated from ironing clothes. Grandma, watching her charges play on the beach, pours sand to cover the age spots on her legs. The ensemble comes together in moments of shared joy at the seaside or watching the fireworks at the Sumida River festival.

But these moments don’t prepare us for the unsettling revelations about the characters’ pasts that we get in the last half hour. Even here, though, the details of behavior remain indelible. One astonishing shot turns a cinematic staple—a woman trying to wipe away tears—into a tour de force of facial performance by Ando Sakura.

The Shoplifters reminded me of Ozu’s Passing Fancy and Inn in Tokyo, obliquely but sharply condemning the economic conditions that push people into wayward lives. It’s a gently subversive film about people flung together resourcefully trying to survive and find happiness by flouting the comfortable norms of middle-class morality.

Time out of mind

A Land Imagined.

Lush Reeds, by Yang Yishu, has plenty of the long takes that Girls Always Happy avoids. In nearly abstract framings, newspaper reporter Xiayin moves through minimalist offices and country lanes, bleak apartments and dense foliage.

As in many postwar films, drama sometimes becomes subordinate to the walks taken by the protagonist into an overwhelming, mysterious environment.

Against the wishes of her politically cautious editor Xiayin inquires into complaints of rural pollution. At the same time, she’s pregnant and is growing distant from her fairly cold husband. Her visit to the countryside becomes a threatening experience that brings to light parallels between the death of a villager and the apparent suicide of a fellow reporter.

The film is less linear than I suggest. Yang breaks up the story into midsize chunks and sets them out of order, so that some images–a little girl who meets Xiayin in the village, a shoe on a riverbank, the rescue of a suitcase from a rubbish depot–could fit into one time frame or another. Yang is even so bold as to run the title credit again midway through the film, suggesting that what follows might be backstory, or imagination, or an alternative film, or something in between.

A similar ambiguity pervades A Land Imagined (2018), another prize-winner (Golden Leopard, Locarno). It centers on a migrant worker Wang working at a Singapore site devoted to extending the coastline with sand dredged up or brought from other countries. Wang has disappeared, and the investigating cop Lok soon learns that Wang’s Bengali friend Ajit has vanished as well. A flashback takes us into the backstory, showing Wang spendiing his nights at a cybercafé and getting harassed by a troll who invades his videogame screen. Wang also begins a chaste affair with the tough gamine Mindy who oversees the game parlor. Eventually the flashback turns into a parallel, dreamlike narrative, with Ajit by turns dead and alive and Lok reenacting scenes involving Wang.

Director Yeo Siew Hua has given this noirish tale an appropriately lustrous treatment, with saturated long shots of black derricks looming against a red sky or sunk in sickly orange murk. Lyrical slow-motion musical interludes enhance the dreamlike ambience, and there’s a post-Wong-Kar-wai freedom of camera placement in the candy-colored cybercafé.

In his comments after the screening, Yeo spoke of trying to provide a counter-image to “the postcard, Crazy Rich Asians” depiction of Singapore. The shifting time frames and uncertain stretches of subjectivity are connected, for Yeo, with a sleeplessness suffered not only by the main characters but also by the population at large. The “land imagined” isn’t only the sand that expands the contours of the shoreline but also the hallucination of a hypermodern city state built on the labor of workers who can conveniently go missing.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Girls Always Happy.