Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Our contributions to FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel continue. Last month brought Jeff Smith’s analysis of musical motifs in Foreign Correspondent and his celebration of the skill of Alfred Newman, supplemented by a blog entry here. This month it’s my turn, taking on Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata (1943; all Japanese names hereafter in Western order, family name last). My presentation is here, if you are a FilmStruck subscriber. A bit of it is available to all at the Criterion site. Today’s entry fleshes that out with some contextual background.

If the streaming version of Observations on Film Art is a bit like a bonus material on a DVD, think of these blog entries as liner notes with clips. This format allows us to tackle the films from an angle not covered in our videos. We’re sorry that not all of our readers can access the Criterion Channel. But if these entries inspire you to go back to the films in whatever form you can find them, that would be all to the good.

Conquering the self

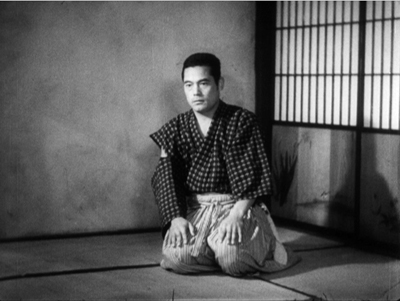

Sanshiro is a film à clef, using martial arts to promote a nationalistic cultural pride. The character of Sanshiro was based on Shiro Saigo (above), who was one of the first pupils of the founder of judo, Jigoro Kano. (In the film, Kano is called Yano, below.) Kano learned the traditional fighting technique called jujutsu (aka jujitsu). Like jujutsu, judo involves grappling, locking, and throwing, and it deploys the opponent’s force against him (or her). But Kano tried to refine the art, eliminating some of the harsher techniques, like biting and kicking, and aiming for maximum efficiency of energy.

By treating judo as a sport and encouraging sparring and public matches, Kano led judo to prominence. His pupils defeated jujutsu challengers. In 1885-1886 matches against Tokyo police champions, Kato’s star pupil Saigo proved judo’s prowess.

In the hands of Kano and Saigo, unarmed fighting techniques were turned to spiritual ends. Ju-jutsu, “flexible technique” was replaced by ju-do, “the path of flexibility”—a devotion to a way of life rather than mere mastery of grips and throws. This distinction is enacted in the film, when Sanshiro, having learned enough technique to bully people with abandon, must learn to master himself.

Judo’s emphasis on spiritual seeking fitted an ideology that emerged in the Meiji period (1868—1912). Japan’s elite was bent on incorporating Western technology and social institutions while maintaining, or rather constructing, a distinct national identity. Accordingly, jujutsu, whose origin lay in Chinese boxing, came into disfavor as part of “feudal” traditions. With young people becoming entranced by Western sports like boxing and wrestling, the government encouraged the development of judo as both modern and uniquely Japanese. As often happened, these “inherently Japanese” cultural forms were of recent invention.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

There’s another dimension to the story. John Dower has pointed out that imperial wartime propaganda tended to emphasize not triumph over the enemy but the need to purify the self. Accordingly, judo’s victory in the social sphere parallels Sanshiro’s conquest of his anger and egotism.

In the film, Sanshiro comes to Tokyo in 1882, the year Kano actually founded his school. After training, both physical and spiritual, the young man proceeds to defeat the surly jujutsu master Monma. Bristling with youth and vigor, Sanshiro then comes to represent a rising generation capable of surpassing its elders. The next fight references Saigo’s most famous combat during the 1886 police tournament. He must defeat the kindly jujitsu master Murai. But he is attracted to Murai’s daughter Sayo, and so it pains him to trounce her father. But Murai acknowledges judo’s superiority and easily forgives Sanshiro. Judo, he says, awakens his senses.

Most intently, Sanshiro’s purity of spirit clashes with the foppish, Europeanized Higaki, who exploits judo for aggression and self-aggrandizement. Their big fight comes on a wind-swept hillside, perhaps a reference to Saigo’s signature technique yama-arashi (“mountain storm”). The polarity Japanese/ Western would become even stronger in the film’s sequel, Sanshiro Sugata II (1945), in which Sanshiro must fight an American boxer. But from fight to fight, Sanshiro gains greater and greater self-possession, so that in the climactic combat, he can spare time to stare at clouds and envision lotus blossoms.

The film’s plot reverses Saigo’s actual life course: He became a street brawler after he won his tournament victories. More basically, Sanshiro Sugata goes beyond its historical sources and political program, as ambitious films tend to do. Nationalistic messages appropriate to wartime are transformed, reworked—”cinematized”—through Kurosawa’s remarkably dynamic approach to film style.

A resumé film?

Sanshiro is a young man’s first film. Kurosawa started on it when he was thirty-two (within my magic-number deadline). In the Criterion Channel video, I treat the movie as an occasion for an ambitious director to display his versatility—a sort of resumé film, as we’d say nowadays, and maybe a little showoffish.

He was ready for the project. He had a busy several years as an assistant director and screenwriter at the fast-moving Toho studios. He worked on twenty-eight dramas and comedies between 1936 and 1942. When he read Sanshiro’s source novel upon publication, he urged Toho to buy it, and he plunged into his project with fervor.

Like other young directors in Japan, he was well aware of developments abroad. His autobiography records seeing many imported films, from Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930). Interestingly, he claims to have seen Storm over Asia (1928), Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher (1928), Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and even films by Buñuel and Man Ray. His viewing included Hollywood fare by Ford, Lubitsch, Borzage, Wellman, Sternberg, and others. Indeed, he could have kept up with American cinema right up to Pearl Harbor; prints of Edison the Man (1940), Morocco (1930), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) seem to have been playing in Tokyo in late 1941. Then all American films were banned.

So he was a cinephile director, perhaps not quite as passionate as Ozu, but a young man who looked and learned. Like most Japanese directors, he had mastered Hollywood continuity staging and cutting. I’ve argued elsewhere that many of his contemporaries were bolder stylists than the Americans. Whether it’s a matter of long takes, camera movements, rapid cutting, or subtle transitions—the Japanese found their own striking innovations.

Ozu’s distinctive 360-degree staging space, low camera height, and play with graphic editing constitute an extreme example of Japanese pictorial invention, but he wasn’t alone. Take this passage from Naruse’s Street without End (1934). The heroine has left her husband’s hospital bed after denouncing him, his mother, and his sister for selfishness. Servants and family rush past her; he may be dying. She hesitates in the corridor. Should she return?

The pattern of cuts and frame entrances accentuates her uncertainty—taking a step, and halting—while the clashing directions in which she moves (right, left, right) have a Soviet-montage flavor. So do the blank frames at the start of every shot, since we have no idea of where we are in the corridor, or where she is, until she thrusts into the frame. And we don’t know whether she chooses to return or not; the geometrical cutting expresses her hesitation.

This geometrical approach to editing is one of the characteristics of Sanshiro I discuss in the video entry. You see it near the start, when alternating single shots of Yano, back to the river, are intercut with slow tracking shots across Monma and his truculent students. To push the pattern further, the tracking shots alternate—first in one direction, then another. Like two rhyming lines in poetry, each of these cinematic couplets brackets one futile attack on Yano after another. Later fight scenes will get more complicated, but display no less rigorous a patterning. And the purpose is always to add to the tension and excitement of the combat.

Another sort of pattern we find in Sanshiro is simpler, but Kurosawa works some nifty variations on it. It’s also somewhat geometrical, but it serves mostly to accentuate a moment of stillness. This is the axial cut, the shot change that moves in or back along the axis of the camera lens. The effect is of sudden enlargement or de-enlargement, a popping out toward the viewer or a sudden withdrawal. Like most directors, Kurosawa uses the axial cut to enlarge something–here, Sayo’s act of praying for her father at a temple.

When the axial cut is justified as a character’s viewpoint, it has the effect of signaling a sharp narrowing of attention. This happens here, when we realize in the voice-off remark (“How beautiful”) and a fourth shot that Yano and Sanshiro have come upon her. That exemplifies an axial cut that moves backward rather than inward.

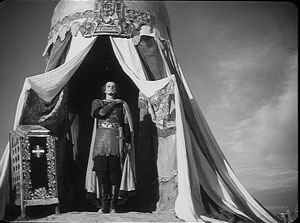

I discussed Kurosawa’s fondness for axial cuts years ago, but it’s interesting to see their origins here. They’re present from the earliest years of cinema, but Kurosawa, again like the Russians, used them expressively. Most uses in Hollywood consist of just two shots, a long shot and then a closer one on the camera axis. But the Soviets, perhaps starting with Eisenstein, multiplied the number of shots and made them fairly brief, so the effect is of a person or object punching out at the viewer. Eisenstein uses the device throughout his silent films, but in both Alexander Nevsky and the two parts of Ivan the Terrible, he develops the device in a very virtuoso manner. Here’s Ivan, standing above the battlefield.

Eisenstein adds to the popout effect by cheating Ivan’s position between shots, so he jumps forward out of his tent.

I’ve found some axial cuts in Japanese films before Kurosawa started directing. One of the most “Kurosawa-ish” comes in a minor 1939 Nikkatsu swordplay film called Faithful Servant Naosuke (Chuboku Naosuke). Again, the cut-ins emphasize a poised moment.

Even if Kurosawa didn’t invent the technique, he made it more prominent and percussive in Sanshiro. It makes the pauses within combat as staccato as the action of fighting. I spend some time in the video talking about how this all works in particular scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, The Most Beautiful (1944), itself a real beaut, uses the technique quite differently, mainly for tension. His later films continue to explore its possibilities. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 (1945) resorts to the device to express our hero’s lingering departure for the big duel. He trots toward us, and each time he pauses to look back, Sayo bows.

Today’s filmmaker would probably pull us back with a tracking or crane shot, but by relying on editing Kurosawa gives us his typical crisp geometrical patterning. The abrupt cuts underscore Sanjuro’s realization that he may not return from this life-or-death confrontation. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2, along with the first film and The Most Beautiful, is available from Criterion, as a disc and on FilmStruck streaming.

My streaming presentation discusses other cinematic strategies Kurosawa employs, but these remarks should give you a sense of just how energetically creative he’s being in his first film. It’s a very flashy item, and it looks far into the future. Decades of kung-fu films have been based on dueling dojos, rival fighting methods, and escalating challenges. In addition, Kurosawa’s technique, moving lightly under the weight of an official message, seems very modern.

Youthful, too. As he told Donald Richie, “I really make my films for people in their twenties.”

The information about the history of judo comes from Gabrielle and Roland Habersetzer, Encyclopédie des arts martiaux d’extrême orient (Amphora, 2000), 265-268, 300-301, 549, and 765. Kurosawa lists films he saw in his youth in Something Like an Autobiography, trans. Audie Bock (Knopf, 1982), 73-74. John Dower’s discussion of Japanese propaganda is in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1987). The closing quotation comes from a 1962 conversation reprinted in Akira Kurosawa Interviews, ed. Bert Cardullo (University of Mississippi Press, 2008), 8. Thanks to Hiroshi Komatsu for information about Faithful Servant Naosuke.

Street without End is available in the Criterion Eclipse collection Silent Naruse. If you don’t have this set, get it pronto.

Informative books about Kurosawa and Sanshiro include Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa third ed. (University of California Press, 1999); Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, rev. and exp. ed (Princeton University Press, 1991); and Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune (Faber, 2001). Especially revealing about Kurosawa’s production methods in his later films is Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). On the “spiritist” trend in government policy in the media of the period, see Peter B. High’s magisterial The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), Chapter 6.

For more on axial cutting in Soviet and modern films, and The Simpsons, go here. I discuss Eisenstein’s axial cutting in The Cinema of Eisenstein, Chapters 2, 4, and 6. On Ozu’s characteristic staging, shooting, and editing system, see my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available for download from the University of Michigan Library site. The full PDF takes a while to download, but you can get access quickly by clicking on “List of all pages.” I discuss other aspects of the tradition from which Kurosawa comes in Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 12 and 13. See also the Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Shimizu entries on this site.

Kim Hendrickson, Criterion producer, and Grant Delin, DP, filming DB from a closet.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: The advantages of leaving home

Kristin here-

David and I are in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato. Once again there is an overwhelming choice of films on offer, demanding a patient acceptance of the fact that one cannot possibly see anything close to everything one wishes. Careful planning can only do so much.

If there is anything I have learned from the films in the first half of the festival, it is that one should not leave home. In the earliest surviving Mizoguchi Kenji film, The Song of Home (1925), a talented but impoverished young man accepts the idea that staying in his village is best for both himself and Japan.

Nearly thirty years later, Girls in the Orchard (dir. Yamamoto Kajiro, 1953), the heroine must choose between going to Okinawa with her fiancé or marrying a man who can help her maintain her family’s traditional pear farm. Naturally, she makes the right choice.

The heroine of Ousmane Sembène’s first feature, the pioneering Senegalese film La noire de … (aka Black Girl, 1966) leaves her home country for France and the better life she dreams of, only to find herself virtually imprisoned working as a maid in Antibes.

The lesson is clear, and yet those of us who have ventured from around the world to Bologna are all the better for it.

Color blooms in Bologna

Color films have always featured on the program at Bologna, but this year various processes are on display in more threads than usual. While the past three festivals have offered a lengthy retrospective of early Japanese found films, this year’s it’s early Japanese color films. There are vintage Technicolor prints in one series, restored color from the silent era in several threads, and eye-poppers like Cover Girl among the restorations being shown off by various archives and labs.

The first screening on the opening afternoon of June 27 was The Thief of Bagdad–not the Fairbanks silent but the 1940 British version co-directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, and Tim Whelan. I must have been one of the few in the vast Arlecchino theatre who had never seen it, even in a faded 16mm print. Some were there to recapture the fond memories of their youth.

As a “vintage” print, it had an odd history. This was not a vintage re-release print, as some of us expected. It stemmed from the 1990s chemical restoration which was subsequently digitally scanned. The images looked like the Technicolor films of my youth (not quite the 1940s, but at least the 1950s). It was a relatively early film using the three-strip Tech process, which had really only reached its ideal form in Hollywood as recently as 1939, with The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

This print had the eccentricities of the three-strip process. Some shots had poor registration, with red and green rims around the characters, while others were in perfect alignment. The matte lines for the numerous fantastical effects (flying horse, giant jinn, flying carpet) were very obvious, and the color changed suddenly for every dissolve. The print was probably not a bad indication of what audiences would have seen at the time.

The design certainly took advantage of the color process, with numerous false-perspective sets and costumes carefully arranged to show off the range of bright hues that Technicolor could achieve (above).

As for the film itself, it is extremely charming without being one of the masterpieces of the era. It suffers from having a bland pair of actors as Ahmad and the princess who loves him, and Sabu is perhaps a trifle too irrepressible as the titular thief, Abu. Miles Malleson, the comic character actor who co-scripted the film, steals the show as a Sultan so obsessed with elaborate mechanical toys that he trades his daughter to the villainous Jaffar (Conrad Veidt, acting rings around much of the cast) for the flying horse. It was an epic in its day and perhaps helped give rise to the many Technicolor fantasies of the 1950s.

A different sort of range was shown off in a program of silent films restored by the EYE Filmmuseum of the Netherlands. These included hand coloring, as in a 1915 short documentary preserved under its English title, Dutch Types, primarily consisting of shots of villages and schoolchildren.

A 1913 Italian film La falsa strada (dir. Roberto Danesi) was a tinted print. It starts off with a familiar situation of an opera singer giving up the stage to live a quiet life on her rich husband’s country estate. One might expect a young lover to rescue her from her boredom, but instead her very lively show-business friends from the city visit and cause the husband to be jealous of the singer’s apparent preference for their company over his. Unfortunately the final reel was missing.

Even more incomplete was Una notte a Calcutta (dir. Mario Caserini, 1918, right). Only a couple of scenes totaling eleven minutes survive, but they show off the talents of diva Lyda Borelli and suggest that the settings and costumes for this otherwise lost film were impressive.

The emphasis on color promises to continue next year, as with the hints dropped concerning further early Japanese color films to come on a second program.

The auteur of the year

Following a long-established tradition, the festival includes a retrospective of a Hollywood director, Leo McCarey. Having seen quite a few of the films on offer, I haven’t followed this thread faithfully. I fondly remembered Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) from a single 16mm viewing many years ago, though, and decided to watch it. I was glad I did. For a start, it was a mint 35mm print and a joy to watch. Moreover, I had remembered Charles Laughton’s performance as hopelessly mannered and eccentric. This time I caught many of the subtle gestures and glances that he used to convey the thoughts of a character who, at least in the early scenes, speaks little and then only very formally. The supporting cast is ideal for the witty script that condenses the overly long original novel.

McCarey got his start by directing two-reelers with some of the best second-tier slapstick comics of the 1920s, including Charlie Chase, Max Davidson, and Mabel Normand. One program of three showed off each in turn. The Uneasy Three (1925) casts Chase as an aspiring burglar invading a society party with two partners-in-crime sneaking in by impersonating a trio of classical musicians. Don’t Tell Everything (1927) has Max Davidson marrying a wealthy widow, only to have his obnoxious freckled son (Spec O’Donnell, as always) worm his way into the household by disguising himself as a surprisingly convincing maid. Finally, Should Men Walk Home? (1927) teams Creighton Hale and Mabel Normand in another stealing-a-brooch-from-a-society-party plot. Normand gives a late, great performance. (Imdb lists this as her penultimate role.)

The World Cinema Project restores another three

I always try to see the latest films restored by the World Cinema Project, which aims to save important movies made in countries that do not have the archives or resources to protect them. This year the films were La noire de …, Sembène’s first feature, Ahmed El Maanouni’s Moroccan film, Alyam Alyam (aka Oh the Days, 1978), and Lino Broca’s Insiang (the Philippines, 1976).

La noire de … deals with the post-colonialist effects of French rule in Senegal, with the heroine Diouana (below) eager to visit the France of her dreams. Once there, she is never allowed to leave the apartment of the French couple who has employed her; they told her she was to care for their children, but she is relegated to household tasks.

Our friend Peter Rist recalled seeing this film with a color sequence, but this was not included in the restoration. The informative panel introduction to the film, led by Cecilia Cenciarelli of Project, revealed that a sequence showing Diouana’s arrival in Marseilles was shot in color. The idea was to show the heroine’s hopeful view of her new country, contrasting with the black and white of the rest of her film as that hope dissipates. Cenciarelli said that there is no clear evidence that Sembène intended this color scene to be part of the final film. If it survives, it would make a valuable supplement to a future home-video release.

Going from Ruggles of Red Gap to Insiang was an experience in contrasts of the sort one often has here. Insiang is the film’s heroine, a laundress living in a Manila slum. The film was shot in a poverty-stricken area and incorporates many candid shots of children playing in mud and puddles. Much of the action involves shiftless young men who drink and gossip as the women around them do most of the work (above). Against this reality-based milieu, Brocka sets an extremely melodramatic story of Insiang and her mother competing for the affections of the same wastrel. One suspects that Brocka was trying to make his grim film palatable to a broader audience, but the film was a financial failure.

Maanouni took a very different approach for Alyam Alyam. There is a minimal plot about a young peasant earning money to travel to France or the Netherlands for work. This character and his mother and grandfather,  who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

In introducing the film, Maanouni said that he wanted to question why Morocco cannot provide the opportunity and incentive to keep young people from leaving. By emphasizing a lyrical depiction of the countryside and the impossibility of earning anything but a subsistence wage, he makes vivid the sad waste of the nation’s potential–a problem that has persisted for decades since the film was made.

The unending march of restoration

The one theme that persists from festival to festival is the thread of re-discovered and restored films. The screenings and, increasingly, the panels and lectures on archival methods, reminds us of how expensive and difficult this process is and how much work goes on each year.

The main film I have seen so far among the restorations is Julien Duvivier’s little-known 1939 film, La fin du jour. (A restoration of his more famous Le belle equipe, 1936, was also shown this year.) It’s the story of a group of actors living in a chateau supported by private charities and dedicated to taking care of aging thespians. They play out their individual dramas against the backdrop of a threatened bankruptcy of the home and a dispersal of its inhabitants to various government hospitals across the country.

There are three primary stories. Cabrissade (Michel Simon) maintains his claim to dramatic fame despite having been only an understudy, and that to a star who never missed a performance. Now entering the home and disturbing its equilibrium is Saint-Clair (Louis Jouvet), an unrepentant seducer and liar. Marny (the less famous but excellent Victor Francen) is a successful actor depressed over his wife’s death, perhaps by suicide, after she ran away with Saint-Clair.

There are numerous small plotlines played out by skilled character actors of the era. The ensemble is interwoven in an impressive example of the “Cinema of Quality,” here practiced by scriptwriter Charles Spaak in collaboration with Duvivier. The tale briefly becomes maudlin toward the end but overall is a touching and often funny depiction of old age among a group particularly reluctant to face that time of life.

In the second half of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I’m concentrating on a small retrospective of Iranian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as a long-awaited restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy.

David’s book Figures Traced in Light discusses how The Song of Home displays Mizoguchi’s early mastery of Hollywood-style staging and cutting, before he went on to try considerably different techniques.

Thanks to Manfred Polak for a correction regarding La noire de … His blog entry on the film is here.

La noire de… (Ousmane Sembène, 1966).

Pixels into print: The unexpected virtues of long-winded blogging

Penance (2013).

DB here:

Remember Web 1.0, when blogs were really logs? You know, diary-like accounts of events befalling the writer? The sense that every instant of one’s life needs preserving and broadcasting got absorbed into Facebook and Twitter and Instagram, I suppose. Today blogs are more likely to feature essayistic thinking. People slow-cook their blogs more, it seems to me, and they write in a reflective mode. Since our blog has always been, um, expansive in such ways, I welcome the Ruminative Turn.

Like most academics, we write long for a reason. You need more words to dig into a question. That’s why books exist. But mid-range is good too. The blog format suits specualtive, exploratory work and informal prose that wouldn’t show up in a journal. In this para-academic register, the aim is to spread ideas and information around. A reviewer of the book I mention below puts it well: “democratic, attainable erudition.”

Because we write long, and maybe because we’re a bit chatty, a few of our entries have become published, suitably spruced up, as “real” articles for diverse audiences. Some overseas journals, both print and online, have published translations of pieces available here. Thanks to the good offices of the University of Chicago Press, a gaggle of our entries became a book, Minding Movies. Lately, three of our blogs have wriggled their way into paper—two as DVD liner notes, and a third in an imposing rectangular solid that is sort of a mega-book. All are aimed beyond the academy.

Doing Penance

Two summers ago our friend Gabrielle Claes tipped me to a visit by Kurosawa Kiyoshi, accompanying a screening of his Penance (Shokuzai) at the Brussels arthouse Cinéma Vendôme. Of course we went, and we had a good time with the film and the Q & A that followed. I duly wrote it up, did a bit of quick analysis, and offered it to the world online.

When the Doppelgänger branch of Music Box Films decided they wanted to distribute Penance on DVD, they asked for the essay. The it’s come out in a good edition (alongside Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal, worth a look, and other genre fare). My essay is preceded by one by Tom Mes of Midnight Eye, who discusses the film’s relation to its source novel and pinpoints its exploration of “the gray area between the mundane and the ghastly.” there’s also an informative interview with Kurosawa.

As a five-part TV series, Penance fits its plot to the installments pretty rigorously. A little girl is assaulted and murdered, and only her four playmates have seen the killer. Taking advantage of the serial structure, Kurosawa begins each episode by revisiting the original crime, picking details relevant to what we’ll see but expanding the sequence a bit by tracing each girl’s efforts to notify the community. It’s a sophisticated version of the “Previously on [name of series]” recaps we commonly get in TV serials.

After revisiting the killing and showing the aftermath as it affects each girl, every installment shows the children gathering for a grim birthday party. On that occasion Emiri’s mother Asako demands that the girls either find the killer or do penance for their lack of vigilance.

After this juncture, each of the first four installments attaches the narration to one girl’s viewpoint fifteen years later. The episodes trace the awful effects of the crime on the girls’ personalities and their adult lives. Each one gets involved with an unstable man, with catastrophic consequences. In each episode, Asako reappears at a critical moment to demand penance or to absolve the woman. The fifth episode centers on Asako herself: her immediate reaction to her daughter’s death, her search for the killer, and her realization that the crime has roots in her own past.

I was happy to get a chance to see Penance again, because it’s continually engrossing and quite moving. It also exemplifies the sort of clean, classical genre filmmaking that doesn’t get done in America very much. After watching all the GPS views and whooshes down to street level and nonstop bludgeoning supplied by Run All Night (still, an okay movie), it’s a pleasure to turn to a film that builds its tension through a fixed camera, calm clarity, and performances suggesting suppressed menace rather than explosive confrontations–though there are a few of those too.

Penance would be something for young filmmakers to study. It shows how locations can be used elegantly and economically, and how the inability to get extreme long shots in cramped quarters can actually be an advantage. Classrooms, offices, and gymnasiums are used with a sober restraint, each one given defining geometry and color scheme. A crucial confession takes place in a police station being renovated, and Kurosawa lets the scene unfold in a way that continually reveals surprising bits of space, such as a cop standing somewhat ominously at a distance. He’s unafraid of holding long shots because the shot is propelled by the drama, not the cutting pace. Here’s another example that illustrates the Monroe Stahr rules of storytelling: not a car chase or gun battle, but a quietly puzzling situation that evokes curiosity and suspense.

Asako has gone to a drawer and withdrawn a ring. We’ve not seen it before and have no idea what it signifies.

She crosses the room, as if to do something with it. Before we find out, cut to her husband in the hallway. This cut initiates a take lasting over three minutes.

When he reaches the doorway he catches her hurling it angrily into the wastebasket. So now we know he knows…but what?

Reminding her that she’s treasured this since college, he fetches it out for her and quietly leaves.

As she starts to explain, she follows him into the corridor. The camera pans right to reframe their new confrontation.

There she reveals her secret, slowly. As she crumples to the floor, Kurosawa permits himself a camera bobble–a rarity in a film that almost entirely avoids handheld camerawork. The husband at first consoles her…

…but then she confesses her secret. He pulls away from her.

She tries to embrace him, looking for solace, but he shuts her out and withdraws.

She’s left to fall to the floor crying in shame, in that classic attitude of distraught Japenese women.

The highest pitch of the drama–Asako’s revelations–has been given a close view, but the action has led up to it and away from it through character blocking, not cutting. The situation unrolls and builds tension completely through dialogue, body language, and facial reaction. But it could hardly be considered theatrical, because the camera has judiciously strengthened certain parts, concealed others, and obliged us to shift character perspective (Asako-husband-Asako) through slight changes of position. And playing so much of the scene in distant and dorsal shots harks back, inevitably, to Mizoguchi.

As I mentioned in the early entry and the liner notes, Kurosawa always knows where to put the camera–no small accomplishment these days–and there’s as much power in this apparently simple scene as in any of the grandiose Steadicam movements in more inflated films. Trust the audience to sense the undercurrents, and they will follow you if you have mastered calm, precise cinematic storytelling.

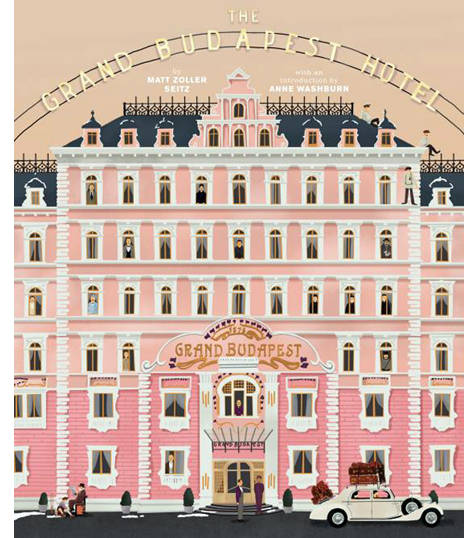

Grand hotellerie

The Doppelgänger gang released Penance on DVD last November. I’m only a little less late in mentioning the arrival of Matt Zoller Seitz’s newest addition to The Wes Anderson Collection: The Grand Budapest Hotel. The decision to base a big, luscious book on a single Anderson film gives this ambitious picture even deeper treatment than we saw in the Collection’s individual chapters. From Seitz’s rich opening appreciation to the amiable list of contributors (The Society of Crossed Pens), the book is a serious divertissement, a wonder-cabinet of images, ideas, and semi-childish fun.

It’s partly a making-of book. We get production stills, script pages, set designs, storyboards, animatics, special-effects secrets, costume designs, and the now-celebrated photochrom images. Seitz has larded his captions with shrewd critical points about lenses, compositions, lighting, and staging—not the normal gee-whiz commentary of an “authorized” making-of. Anderson’s enjoyment of practical effects, his judicious use of digital tools, and his most complex voice-over narration yet come through vividly.

Seitz is especially interested in the history and artistic models behind the movie. His interviews are crowded with information about Anderson’s inspirations, which seem endless. Of course there is Stefan Zweig, who is given several pages of intense discussion. We also learn of Anderson’s interest in the exiled directors like Lubitsch and Wilder, who gave us both a Europeanized Hollywood and a Hollywoodized Europe. There are homages to The Red Shoes and Colonel Blimp and Letter from an Unknown Woman. Anderson was equally committed to a broader historical context, passing his story through different eras—the bell-jar atmosphere before the Great War, the premonitions of World War II (itself never shown), and the postwar emergence of Communism, seen in the revamped and decaying Hotel in the 1960s. Seitz has even spotted borrowings from James Bond movies. As skillful an interviewer as he is graceful an essayist, Seitz induces Anderson to reveal the density of this sweet, sinister movie—the cinematic equivalent of Chandler’s line about a tarantula on a slice of angelfood cake.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

There are as well interviews with Ralph Fiennes talking of the “farce spectrum,” costume designer Milen Canonero ordering up a Prada leather coat for Willem Dafoe, the very great composer Alexandre Desplat explaining his compositional procedures, production designer (and Milwaukee native) Adam Stockhausen discussing the magnificent settings, and DP Robert Yeoman talking about shooting on 35mm.

Anderson’s fussbudget aesthetic meets its match in a book crammed with fastidious minutiae. Whimsy, as Lewis Carroll and G. K. Chesterton understood, escapes coyness only when it’s pursued rigorously. Seitz reviews the careers of the major players in postage-stamp pasteups. When Anderson is revealed as a connoisseur of frame stories, flashbacks, and other fancy techniques we favor on this site, Seitz provides a four-page spread of pick hits of voice-over. Max Dalton, the illustrator, gets the message. With their modestly lowered eyes and sidelong grins, his neo-New Yorker figures swarm these pages but assemble, obediently rank and file, in the end papers.

Most surprising of all for a production dossier, in-depth criticism is not only allowed in the tent but given its turn in the spotlight. Christopher Laverty analyzes the costumes with a precision seldom seen in academic writing, while Olivia Collette contributes an enlightening study of Desplat’s score. Steven Boone examines the art direction, with a special sensitivity to how set designs are fitted to anamorphic optics. Ali Arikan brings his characteristic lucidity to a study of Zweig’s Vienna and the traces it leaves on his fiction and Anderson’s film. The essays show that analytical film books, like volumes of academic art history, can be merit high production values.

My contribution, a revamping and nuancing of an earlier blog entry, looks at how Anderson adjusts his planimetric staging and shooting to different aspect ratios. For me, this assignment was the big time. No academic book, my usual publishing platform, could have illustrate my ideas so splendidly. I’m proud to be among fine company, and I like the fact that people are reading and buying the thing.

Of course very few film books have the built-in audience of a Wes Anderson project. As I wrote last summer, he brings his brand with him. But that isn’t, I think, a bad thing when the results are as lively and lovely as The Grand Budapest Hotel.

Last year I had to go to Hong Kong the weekend the film opened. I dashed to it during my first day in town, then squeezed in two more screenings during the festival. Now, after a year and many more viewings, it hasn’t cracked yet. At the moment I think of it in relation to the “hotel” books and movies of the 1920s and 1930s. I think of its predecessors, such as Arnold Bennett’s 1902 novel The Grand Babylon Hotel. (Did Anderson read it? I don’t find a mention here.) I remember those star-filled ensemble comedies of the 1960s like The Pink Panther and The Great Race, twitching with celebrity walk-ons and the cartoonish effects Anderson relishes. In short, I think about film history, and it pleases me when a film and its book trace out, in dazzling detail, an exceptional movie’s debts to tradition. Keep your Birdman and Gone Girl and Jersey Sniper (or is it American Boys?): This is the 2014 American film that will be remembered for decades.

Hello again, my language

Last year’s other big film for the future is, no doubt now, Adieu au Langage, just coming out on Blu-ray as Goodbye to Language from Kino Lorber. I’ve said my say about this item twice (here and here) so about all I have to add is that after several more viewings, I’m still convinced of its excellence. Kino Lorber gives us two versions, the 3D one and the “merged” 2D one. The 2D one is still one hell of a film, but of course in 3D it’s spectacular.

The disc includes an essay developed beyond my blog entries. It says some new things, but it’s inevitably incomplete. Godard’s films so teem with ideas (both intellectual and cinematic) that there’s almost always more to notice. “One can put everything in a film,” he remarked back in the 1960s. “One must put everything in a film.” He sort of does, especially here.

Both versions belong on every cinephile’s shelf. If I didn’t already have a 3D TV (purchased so I could watch Dial M for Murder and Gravity properly, and even freeze the frame), I’d get one so I could see Farewell to Language whenever I wanted. Consider your options. 3D TV is now dead enough to be cool.

Thanks to Austin Vitt of Music Box films for picking up Penance, and Richard Lorber and Robert Sweeney for recruiting me for the Godard disc. I’m indebted to Matt Zoller Seitz for bringing me on board the Anderson project, and to Caitlin Robinson of Twentieth Century Fox for loaning me a print of The Grand Budapest Hotel so that I could study its aspect ratios in their natural habitat.

Midnight Eye features Kohei Usuda’s very detailed review of Kurosawa’s latest project, an entry in the “idol movie” genre. You can find MZS’s video introducing the Grand Budapest book here.

Goodbye to Language.

Here be dragons, and tigers

Revivre.

DB here:

My first visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival back in 2005 was at the invitation of Tony Rayns, programmer of the Dragons and Tigers series. That series included both new films by established directors and a batch of first or second features by beginners. Tony asked me to be on the jury for the young D & T award.

I enjoyed working on that jury, which consisted of old friend Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong Film Festival and new friend Gerwin Tamsma of the Rotterdam fest. We gave the prize to Liu Jialin’s Oxhide, and it’s been gratifying to track her career since. In the course of my stay I realized what an excellent festival Vancouver had, not least because of the warmth and enthusiasm of its staff.

My Vancouver experience helped launch this blog, which really got under way during my second visit, in several entries in 2006. That was also the year I met Bong Joon-ho, who was at VIFF with The Host. I kept going back, and Kristin began joining me, so every year we’ve been writing about this admirable event.

During that 2006 festival Tony decided to rearrange his commitment to Dragons and Tigers. He turned the curating of Chinese-language films over to expert programmer Shelly Kraicer, who was living on the mainland and had excellent contacts within China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan. Now things have changed again. This year the festival accepted fewer beginners’ features and folded them into a broader international competition. One of the Asian films in the collection, Rekorder by Mikhail Red, tied with a French entry, Miss and the Doctors, for the award. In the old days, the winner received a cash prize; alas, that benefit has not been retained, but maybe some far-sighted patron will step forward to give the award a little more heft.

There were fewer D & T titles overall this year, but I still found several of great interest. Herewith some notes on them.

Time, and time again

Revivre.

If your movie is going to include flashbacks, you have a choice among several standard ways of motivating them. You can use the very old device of presenting an investigation or trial, in which the film translates testimony into dramatized scenes. Or you might frame the flashbacks with a scene of a character who thinks back on events in the past. Three of the Dragons and Tigers films used some other common flashback setups, but treated them in fresh ways.

Im Kwon-taek’s Revivre (Hwajang, his 102nd film!) starts with another canonical flashback situation. In fairly washed-out footage a funeral procession crosses the screen. A man at the head of the group looks back and sees a beautiful young woman looking gravely at him. Immediately the film triggers questions: Whose funeral is this? Why is the young woman important?

The rest of the film fills us in via flashbacks,. The protagonist, Oh Sang-moo, is a manager of the advertising section of a cosmetics company. His wife is stricken with a brain tumor and he cares for her as best he can during her years of surgery and recovery. At the same time, he develops a restrained affection for Ms. Choo, an employee in his division. Eventually Oh’s wife dies and there is the lingering possibility of his starting his life afresh with Ms. Choo, whose phantom face we’ve seen in the procession. Threaded through this are the pressures of a business deadline, his need to keep his staff on track, his occasionally fraught relations with his daughter, and his wife’s adamant insistence that after she dies he keep none of her things, not even her beloved dog.

The film scrambles the order of Oh’s experiences. After the funeral, within about five minutes we get a scene of Oh’s wife dying in the hospital, then a scene of his own medical problems, and then the moment that Oh’s wife collapsed in the garden, yielding the first sign of a tumor. The rest of the film gives us incidents from all phases of their last years together, with emphasis on his careful attention to her bodily functions. Although his daughter finds the task repellent, Oh changes his wife’s diapers and cleans her private parts with the same calm professionalism that he brings to the meetings in his company. In all, the non-chronological flashbacks work effectively to show Oh juggling the pressures of business with the demands of his family situation.

What makes Im’s treatment a little unusual is that the flashbacks aren’t presented as Oh’s memories. They are rearranged by the narrational authority of the film itself, rather than by situations that provoke Oh to recall this or that incident. We’re restricted to Oh’s range of knowledge throughout, but that doesn’t draw us closer to him. We have to read his mind through his expressions and his gestures, and these are often severely controlled. A master of the poker face, this executive keeps a polite distance from everyone, including the viewer. Is he one of nature’s stoics? Or is he emotionally detached, attending to his dying wife more out of duty than love?

These questions are partly answered by some brief fantasy scenes in which Oh visualizes Ms. Choo as a romantic partner. She seems to intuit his interest, and responds through small signals. When she starts to reciprocate more explicitly, Revivre returns to its mood of impassive sadness for its final scenes.

Time and freedom

Hong Sangsoo has been playing with time from the start of his career. He has tried replays from different viewpoints (The Power of Kangwon Province, 1998), replays that differ in details (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 2000), odd déjà-vu experiences (Turning Gate, 2002), and all manner of theme-and-variations plotting (as noted on this blog here and here and here). So it’s a bit surprising to find him exhuming the old reliable setup of letters recounting events in the past. Yet here as ever he has a couple of tricks up his sleeve.

Like Im, Hong has scrambled the flashbacks in Hill of Freedom, but he offers a comically exact motivation. Kwon, a young language teacher in Seoul, returns to find a sheaf of letters written to her by a Japanese admirer, Mori. He taught with her at the school two years earlier. He has come to Seoul to reunite with her, and he has left her a letter every day. She starts to read them in the school lobby, and Mori’s voice-over narration establishes the beginning of his story. He tells how he found lodging, left a note at Kwon’s apartment, and paid his first visit to the “Hill of Freedom” café.

So far, 1-2-3 preparation. But when Kwon starts to leave the language institute, she staggers on the staircase, as if stricken, and scatters the letters on the steps. She gathers them back up in random order. This sets up the scrambled timeline of the flashbacks to come. (Hong mischievously zooms in on a letter she fails to retrieve, hinting at a gap in the story that will follow.)

What Kwon learns, in mixed-up order, is that Mori’s search for her leads him to meet and hang out with his landlady’s nephew, while also becoming romantically involved with Youngsun, the café owner. In the grip of a possessive lover, Youngsun attaches herself to the fairly passive Mori. Their affair plays out in Hong’s usual mix of drinking bouts and pillow talk.

By the time we’re used to this pattern, Hong sets up a new game. As he keeps cutting back to Kwon reading through the letters, accompanied by Mori’s voice-over, Hong gradually reveals that she is reading them in the Hill of Freedom café—the very place Mori hoped to meet with her (but never did).

Eventually, Kwon steps outside for a cigarette, and we suddenly get her voice-over remarking that the last letter was postmarked a week ago. Has Mori then already left and stopped writing? At this point Kwon encounters Youngsun coming in, and they greet each other as friendly acquaintances. The next scene finds Kwon visiting Mori’s guest house.

What happens there shifts the ground under our feet. After talking with friends, I think that we can’t be sure about what’s actually taking place. A mysteriously bruised cheek, a surprise reunion, and the return of Mori’s voice-over fill the penultimate scene. The coda is even more of a puzzler, at least to me. (I wonder if it’s the scene described in the letter that Kwon didn’t retrieve.) In any event, Hong’s usual themes of the foolish arrogance of Korean men and the comedy of male-female interactions are given new expression in this lightweight but enjoyable movie. The fact that Hill of Freedom is mostly in English, which Mori must employ to communicate with the Korean characters, adds to the fun.

Video virus

Yet another trigger for a flashback can be provided by a crisis situation. It might be rather near the story’s climax, so that we are left hanging and the plot takes us back to the origins of the problem. This is what we get in movies like The Big Clock (1947), which starts with our hero hiding out from the police and wondering how he got in this pickle. Or the crisis situation may come earlier in the story, with the flashback again filling in what led up to it before continuing the situation presented in the frame.

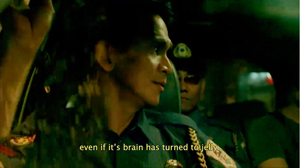

This latter option is followed in Mikhail Red’s Rekorder. After a brief prologue showing violent acts captured by CCTV cameras, we are in a police van with stern cops chatting about killing a dog before we’re introduced to the shaggy, wasted protagonist Maven riding with them.

From this framing situation we flash back to the reason Maven is in the van. Once a cinematographer in the glory days of Filipino cinema, he’s now a loner using his ancient camcorder to film movies in theatres and sell them to a friend who bootlegs DVDs.

Maven is a compulsive recorder. As the director puts it, he is “a ghost in the city observing everything through his lens.” So naturally he’s filming when a street gang kills a young man in front of a crowd who simply watch. Maven doesn’t volunteer his footage, since it includes part of a movie he was pirating. But now he’s been nabbed and is riding to headquarters with the cops, who are very curious about what’s on his tape.

Much of the rest of the film involves Maven’s attempt to keep the cops from examining his footage, while he agonizes about his passive acceptance of street violence. There are still more flashbacks, appropriately presented through old video footage of his wife and daughter. Not until the end of the film do we witness–again, on CCTV footage–the trauma that has turned him into the burnt-out case he is.

Mikhail Red commented that he was inspired to make Rekorder by a viral video in which a youth was shot in the street by thugs and a big crowd didn’t intervene but instead filmed the murder. He staged his own CCTV-style video to supply the denouement, and was shocked to find that it was appropriated in documentaries about street crime. Through a multimedia format, Rekorder updates the sort of social criticism that Raymond Red, Mikhail’s father, brought to Filipino cinema of the 1980s. That era as well is evoked through another sort of flashback, the clips from classic movies that Maven films. “I wanted,” Red says, “to pay homage to the pioneers.”

Straight time

You don’t need to play time tricks to create an uneasy movie. Ow (Maru) presents a typical family squeezed by Japan’s economic stagnation. Dad pretends to have a job, when he actually sets out each day for the unemployment office. Mom and grandma putter about. Grown but spacy Tetsuo lounges about his room talking baby talk. One day, when his girlfriend has just snuggled into bed with him, they are transfixed by a big gray-brown sphere that drifts into his room.

Transfixed, literally. They freeze upon seeing it. So does Dad, and so do the cops who are called. Director Suzuki Yohei introduces us to the big ball with a shot of it slowly spinning, held long enough for us to get slightly hypnotized too. There follows some comic suspense in which people enter the bedroom and may or may not leave. The biggest tease is the reporter who, after learning of a death during the sphere’s arrival, researches the case and then lunges into the room, ranting about a police cover-up.

The tension–will others fall under the spell or the sphere?–is accentuated by shrewd camera setups. When the cops arrive, we get a low-angle shot behind Yuriko and Tetso, showing the frozen cops and a new one not yet transfixed. He pushes one stiff colleague over, revealing the ball, still hovering there, and we wait for him to be the new victim.

Much later, when the reporter first visits the room, the sphere has vanished. But a rhyming angle forces us to remember its presence, and to let the reporter–the source of the plot’s momentum for the rest of the movie–take the place of the hapless cop.

Finally, for another exercise in unkinked time, there is the Korean action picture Haemoo. Produced by Bong Joonho, it centers on the desperate captain of a fish-trawler who agrees to bring illegal immigrants into Korea. Everything that could go wrong does: storm, fog, Coast Guard patrols, a horny crew, and an idealistic novice seaman who tries to protect a woman. Everything, including the accident that creates a horrifying midway turning-point, is carefully prepared in the film’s opening scenes. The film’s second half locks us into the relentless consequences of covering up a huge crime.

The pace is so snappy that I expected lots of cutting, but I counted only about eight hundred shots in 106 minutes. (The Equalizer, only twenty minutes longer, has three times that number.) I attribute this cutting rate to neatly functional direction, with no fuss or waste. The ship’s engine room is a cramped set, hazy with steam and dust, and the shots there are finely calibrated to build the drama through depth, fluid camera movement, and our old friend The Cross. The randy engineer’s business of checking the equipment carries him from one side of the shot to the other, while the young seaman shifts around him–first on frame right, then on frame left, then in the center.

The plot has that satisfying neatness that is characteristic of Bong’s work, and its forward thrust has no need of flashbacks. We can’t ask for backstory when the upcoming twists are as fast-paced and exciting as they are here. Dragons and Tigers has always showcased not only the experimental films like Ow and Hill of Freedom but also the crowd-pleasers, and Haemoo (which translates as “Sea Fog”) solidly fulfills that mission. Long live linearity!

Hill of Freedom has sharply divided critical opinion. Richard Brody considers it a masterpiece; others consider it fluff. At Fandor David Hudson painstakingly surveys the cut and thrust of the controversy.

Hill of Freedom.