Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Addio Bologna 2014

Okoto and Sasuke (1935).

DB here:

Some final notes on this year’s Cinema Ritrovato. Kristin has more when I’ve finished.

Poland, very wide

The First Day of Freedom (1964); production still.

Revisiting a couple of the Polish widescreen classics Kristin mentioned earlier, I’d just add that The First Day of Freedom struck me as merging that heaviness often ascribed to Polish cinema with casual shock effects, as much visual as dramatic. It’s not just the opening shot, with the camera descending implacably to reveal layers of activity in a POW camp before settling on barbed wire in the foreground, made as big as the chains on an ocean liner’s anchor. A symmetrical vertical lift ends the film, rising through floors of a nearly destroyed church tower, revealing a half-shattered Madonna and a looming bell, to float back up to the sky.

As in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, gunfire not only cuts you down but sets you on fire. A Nazi dead-ender, holed up in the steeple and dying from his wounds, orders his girlfriend (“Whore!”) to take over his machine-gun nest. Since she’s been raped by wandering refugees early in the film, she has every reason to fire on the Poles, which she does with animal abandon. A Polish bullet cuts short her shooting spree, and then the camera launches on its remorseless movement heavenward. The primal force of this movie, especially the climax, suggests that Alexander Ford and Samuel Fuller have more in common than I’d suspected.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Yutkevich seems to be keeping up with the Young Cinemas of his day. The film is plotted as a series of flashbacks, alternating the present (Lenin in prison) with pieces of the past, sometimes out of chronological order. He imagines himself striding across a battlefield, conveyed by him walking in place against a blatant back-projection. Late in the film, newsreel footage gets stretched and distorted to fill the ‘Scope format, as in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962). The experimentation with the soundtrack seems likewise rather modern. The noises are filtered nearly as strictly as in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu, so that sometimes we hear only Lenin’s footsteps in a city street.

Lenin not only narrates the film but “quotes” the whole dialogue of the scenes; we never hear any voice but his. Reminiscent of passages of The Power and the Glory (1933) and the entirety of Guitry’s Roman d’un Tricheur (1936), this device blankets the movie with Lenin’s thoughts, feelings, and political analyses. It’s scarily evocative of that booming voice-over narrator that Soviet cinema imposed on imported films. Denied subtitles and dubbing, audiences were obliged to listen to an impersonal voice drowning out the actors with its sovereign interpretation of the action. I wouldn’t put it past Yutkevich to be slyly alluding to this Orwellian voice of authority.

1914 fashionistas and 1940s fakers

Maison Fifi (1914).

For sheer dirty fun I have to recommend Maison Fifi by Viggo Larsen, a Danish director working in Germany. Here situation comedy meets notably horizontal sight gags. A young couturier cozies up to the officers stationed in her town, hoping that their wives will buy her wares. Her first encounter takes place outside the officers’ quarters, as each man, from private up to general, spots her and starts to flirt before being ordered aside by a higher-up. Part of the humor comes from the strict adherence to the table of ranks, part from the fact that each dislodged officer enjoys watching his superior get taken down.

Later, on a lark, some officers swipe one of Fifi’s dummies and take it to a tavern. When their wives surprise them there, they stow the mannequin in a distant phone booth. As they expostulate with their wives in the foreground, the dummy sits unmoving in the window of the booth far on frame right. Meanwhile, increasingly annoyed customers line up outside the booth. The dummy is more visible in projection than in my still, but Larsen also obliges with a cut-in.

In a very logical reversal, Fifi is at the climax caught in a boudoir and must pretend to be one of her own mannequins. This affords the officers an excellent pretext to undress her. Today the scene yields a vivid sense of the hooks, buttons, and stays that women, and men, of 1914 had to contend with.

Faked identity was a motif of the festival’s Hitler strand. The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler (1943) centers on a man with a knack for mimicking his Fuhrer and accidentally becomes his double. In a series of twists, both he and others try to kill the original, but confusion ensues and leads to a very downbeat ending.

The same premise gets a different workout in The Magic Face (1951), a film as puzzling as its title. Luther Adler delivers a performance at once peculiar and virtuoso. A stage impersonator’s wife is stolen away from him by Hitler. Escaping from prison, he decides to get his vengeance by posing as a servant and gaining access to the dictator. He kills Hitler and takes over his identity. Thereafter he cunningly fouls up the prosecution of the war by an ill-timed invasion of Russia, etc. His general staff are baffled and even try to kill him, but he represses all resistance.

The weirdness of this speaks for itself. In addition, the film doesn’t explain how Hitler’s new mistress fails to realize that her paramour has been replaced by her husband. Perhaps more striking, we wonder whether the impersonator might have taken a little trouble to alter other Nazi policies, e.g., the Final Solution. No less odd is the frame story, narrated by celebrated war correspondent William L. Shirer. There he maintains that this account was relayed to him by the wayward wife, who survived the fire in Hitler’s bunker. An independent production directed by Frank Tuttle (recently under HUAC pressure for his Communist affiliations), The Magic Face was judged by Variety to provide “a dramatic and suspenseful story which would have had far greater audience impact five or more years ago.”

Talking, in and out of sleep

The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933); production still.

The Japanese cinema of the 1930s through the 1960s has been one of the very greatest national film traditions. I once characterized it as the Western cinephile’s dream cinema: a relentlessly commercial industry that has given us dozens of indisputable masterworks. Yet it seems that every few years it’s necessary to remind western publics of this nation’s titanic accomplishments. Packages circulated by the Japan Film Library Council in the 1970s have been followed by retrospectives and one-off touring programs at rather long intervals; the Mizoguchi series is a recent example.

Another effort to draw Japanese cinema to the spotlight, “Japan Speaks Out!” has become a high point of Cinema Ritrovato over the last three years. Curators Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström deserve credit for assembling new prints of early talkies, grouped by studio. As in previous years, some of the titles were familiar to specialists, and a few to generalists (Ozu’s The Only Son being this year’s example). But there have been several new discoveries, and the Ritrovato audience has responded enthusiastically. This year the films were screened twice, often to jam-packed halls. The sessions were introduced with brevity and point by Alexander, Johan, and Tochigi Akira of the National Film Center of Tokyo.

This year’s batch focused on the Shochiku studio, more or less the MGM of Japan. Shochiku enjoyed financial stability because of its theatre holdings (both cinemas and live-performance venues) and its address to a modernizing, western-leaning urban audience. Its policies, overseen by Kido Shiro, aimed to provide movies mixing tears and laughter. Kido urged that Shochiku comedy have a melancholy cast, and that Shochiku melodrama indulge in lighter moments. This blend is familiar to us in Ozu’s 1930s works; even as sad a film as The Only Son displays a comic side when the mother falls asleep during a German talkie.

Perhaps the purest example of Kido-ism in this year’s package was one of Shimazu Yasujiro’s best films, Our Neighbor Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934). Two brothers are introduced practicing baseball, and soon we learn that one has considerable affection for the girl next door. The neighboring families are thrown into quiet turmoil when Yaeko’s sister returns home, having left her husband.

Stylistically, Shimazu is less rigorous than either Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi, but he is very skilful. Our Neighbor Miss Yae has the real Kido flavor, mixing comedy and drama and throwing in cinephile references that the studio’s young directors enjoyed: one boy is compared to Fredric March, the young people watch a cartoon featuring Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. Just as important, Shimazu enjoys throwing in a stylistic flourish every now and again–a striking, even eccentric shot that arrests our attention. As the four young people are eating in a restaurant, a very straightforward shot of them gives way to a bold composition full of peekaboo apertures. The shot enlivens the fairly routine act of waitresses delivering food; at the end, one pair stands and switches positions.

Not all Shochiku films displayed a mixed tone; we saw some fairly pure comedies and melodramas. Three self-consciously modern films showed an amused, slightly sexy concern with young marriage. Happy Times (Ureshii koro, 1933) by Nomura Hiromasa, begins with a pair of teenage boys practicing pitching and catching to the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home.” Soon they’re spying on newlyweds who are so infatuated with one another that the husband skips work to stay at home and lounge around. He’s mocked by his fellow employees and upbraided by his boss, but his wife is relentless in her sweet-talking ways. The marital bliss is disrupted by an obstreperous visiting uncle, and the couple must turn to one of the man’s old girlfriends, a tough singing teacher, to dislodge him—without sacrificing the inheritance he may leave them. Awkwardly shot and rather too prolonged, the film exemplified how loose-limbed Shochiku comedy could get.

A brace of films by Shochiku stalwart Gosho Heinosuke, The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (1935) and The Groom Talks in His Sleep (Hanamuko no negoto, 1935), showed other newlyweds with comic problems. Again the motif of spying plays a role. (Naughty voyeurism was essential to that strain in popular culture called Ero-guru-nansensu, “erotic-grotesque nonsense.”) Salaryman Komura’s pals have learned that his wife talks in her sleep, and so they drop by to hear for themselves. Unfortunately they drink so much that they fall asleep and miss the big revelation. Plot complications include a burglar, the couple’s decision to sleep elsewhere, and the revelation of what keeps the bride “sleep-talking.”

Only a little less slight is The Groom Talks in His Sleep. Here the title probably gives away too much, because the initial puzzle is why the young wife naps during the day. This scandalous dereliction of housewifely duty leads eventually to a demand for divorce until the cause, the husband’s sleep-talking that keeps her awake all night, is revealed. The family brings in a self-styled hypnotist, played with relish by Ozu regular Saito Tatsuo, to cure the groom.

Gosho is said to be the fastest cutter among classic Japanese directors, but I’m not sure that he goes much beyond what was fairly standard at Shochiku. Most of the studio’s directors working in the contemporary-life genre (gendai-geki) employed what I called in my book on Ozu “piecemeal découpage,” a breakdown of action and dialogue akin to that seen in late US silent films. What Gosho does have in abundance is different camera positions. In The Bride, our introduction to Komura’s drinking buddies takes place at a bar, and I didn’t spot any repeated setups. Throughout the two films, each composition is calibrated to a specific item of information—a line of dialogue, a reaction shot, or a change in the staging. This makes for a tidy visual texture, which is an advantage in the rather loose plotting that’s characteristic of Shochiku comedy (Ozu, always, excepted).

At the other extreme were some very serious drama, such as Mizoguchi’s relatively well-known Poppies (Gubinjinso, 1935) and the more obscure Mizoguchi-supervised Ojo Okichi (1935). There was as well Okoto and Sasuke (Shunkinsho: Okoto to Sasuke, 1935), another Shimazu work. It’s based on a Tanizaki Junichiro tale of male devotion passing into love and masochism. Okoto is blind, but her family can afford to pamper her. She takes up the koto and the family’s young servant Sasuke faithfully escorts her to her music lessons. She often treats him disdainfully, but she insists on his company, and so gossip grows up around them. Sasuke’s loyalty is tested when Okoto is wooed by a vacuous but persistent suitor. Spurned, he arranges an attack on her, which triggers Sasuke’s ultimate sacrifice.

Shimazu treats this story with a calmness that builds up tension between the often wilful Okoto and the simple-hearted Sasuke. The discreet simplicity of the film’s technique, excepting the violent climax, can be seen in an almost throwaway moment. Sasuke as been assigned to tutor two of Okoto’s students, and they laugh at his efforts. As they rise, Shimazu cuts to a new angle, putting them the background and showing Okoto is shown growing anxious in the foreground.

Keeping Sasuke out of focus and far back allows Shimazu to stress a micro-movement in the foreground: Okoto’s shift from sympathy for Sasuke to her usual imperious annoyance. After unfolding her hands, she clenches her right hand and softly strikes it on the edge of the brazier.

As Okoto turns to summon him for a mild dressing-down, still keeping her little fist extended, Sasuke has shifted his position slightly so that he is a more active responder to her.

This sort of directorial discretion, so characteristic of classic Japanese cinema, seems today to come from another world.

Probably the greatest revelation of the Shochiku show was another masterwork by the ever-more-impressive Shimizu Hiroshi. A Woman Crying in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933), Shimizu’s first sound film, was given its western premier. It was chosen to exemplify his experiments with sound–experiments that induced Ozu to try his own hand at talkies.

Mining work in Hokkaido brings day laborers by ship, along with women who wind up serving them drinks and perhaps something more. Most of the action takes place in a tavern with a bar downstairs, women’s rooms on the next story, and a small upstairs where the mysterious, somewhat cynical Chuko keeps her daughter. Kenji and his boss become rivals for Chuko, and a young woman drawn into prostitution further complicates the situation.

After only a single viewing, I’m pressed to say much more than noting that Shimizu sacrifices some of his geometrical precision (discussed here) to a more naturalistic treatment of the bar’s space and more experiments with chiaroscuro lighting. A somewhat flamboyant scene, in which our view of a fistfight is mostly blocked by a high wall, shows how Shimazu was trying to let sound do duty for the image. The title has multiple implications: the woman we see crying at the outset is Fuji, the girl initiated into the trade; but at the end, Chuko is weeping. Moreover, as Alexander Jacoby pointed out, the scenes we see are all set in winter, although the ending suggests that the couple that is created will find spring elsewhere. Long unavailable in its Japanese VHS edition, A Woman Crying in Spring is ripe for Western distribution.

Last notes from Kristin

Despite my commitment to the Polish, Indian, and Japanese threads, I was able to fit in a film or selection of shorts now and then.

On the afternoon of the opening day, the first “Cento Anni Fa” program for 1914 included a couple of interesting items. One was La guerre du feu, a French film directed by George Deonola. It dealt with a tribe of fur-clad cavemen who have captured fire but lack the knowledge to create it themselves. Thus they must tend their fire constantly and protect it from a rival tribe. In the course of the action the hero learns the secret to using tinder and flint to generate a blaze. This, it has to be said, was more interesting as an historical curiosity than as entertainment.

Not so the final film of this group, Amor di Regina (Guido Volante, 1913). Its unusual story dealt with a queen of an unnamed country who is having a secret affair with a young soldier. When the latter gets wind of a rebellious group’s plans to assassinate the king, the hero and the queen manage to spirit him out of the palace and away to exile. It struck me that in a more conventional film, the lovers would use the assassination of the king to allow them to marry. Instead they take care of the king in exile and watch for a chance to reinstate him.

Stylistically there were some impressive shots. In one, we see a close-up of the back of the hero’s head, looking out from a terrace at a group of conspirators in the distance sneaking toward the palace, and the camera racks focus from him to them–for 1913, a highly unusual way to handle a very deep composition. If anyone is contemplating a DVD/BD release of some Italian short features of this era, Amor di Regina would be a good choice.

Another 1914 program included the lovely La fille de Delft, which, along with Maudite soit la guerre (which was shown at one of the Piazza Maggiore screenings), is one of Alfred Machin’s best-known films. Its plot concerns a little country boy and girl who are dear friends; a variety-theater owner sees them dancing at a country celebration and takes the girl off to the city to become a star. Seeing it again, I was struck at how marvelously natural the performances of the two child actors (above) was, something that goes a long way to making this film so very affecting.

Despite the fact that all of Tati’s early short films are on the new French boxed Blu-ray set, I decided to see the Tati program on the big screen. Seen again, Gai dimanche (1935) seemed a bit labored in its humor, dealing with two layabouts who hire an old car and persuade several people to purchase day trips to the country. The situation seems more the sort of thing that René Clair could have made work, but director Jacques Berr makes it somewhat leaden.

Soigne ton gauche centers on a gawky farmhand who is mistaken for a boxer by a promoter and ends up in a practice ring with a tough opponent. Tati creates a very Keatonesque situation as the naive young man finds a book on boxing on his stool and proceeds to consult it at intervals (below). As he assumes classic boxing poses, the experienced boxer uses brute force to knock him silly.

The opening and closing of Soigne ton gauche contains a comic, bicycle-riding postman, and clearly Tati recognized the comic potential of the character. In his first directorial effort, L’école des facteurs (School for Postmen, 1946), Tati himself played the postman François, who tries to please his teacher by finding ways to deliver the mail more swiftly. The idea proved so fruitful that the film was remade as Tati’s first feature, Jour de fête. The bouncy music and many of the gags were retained, and the longer film’s success established Tati as a major director and star.

To all our friends and the coordinators of Cinema Ritrovato: Thanks for another wonderful year!

You can watch The Eye’s tinted copy of Maison Fifi here.

Miriam Silverberg’s Erotic Grotesque Nonsense offers a thorough discussion of Japanese popular culture of the 1930s. For more on Kido Shiro’s influence on Kamata cinema, see Mark Schilling’s Kindle book Shiro Kido: Cinema Shogun. I discuss trends in 1930s Japanese film style in Chapters 12 and 13 of Poetics of Cinema. For more on the restoration of Machin’s films, see our entry here.

Soigne ton gauche (1936).

Mizoguchi: Secrets of the exquisite image

Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

DB here:

First things first: Happy birthday, Mizo-san! (He was born on 16 May 1898.)

Secondary things second: This entry is based on a talk I gave a couple of weeks ago at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, Queens, as part of its comprehensive Mizoguchi retrospective. I want to thank my friends David Schwartz and Aliza Ma for inviting me to MoMI.

A fragile and fragmentary legacy

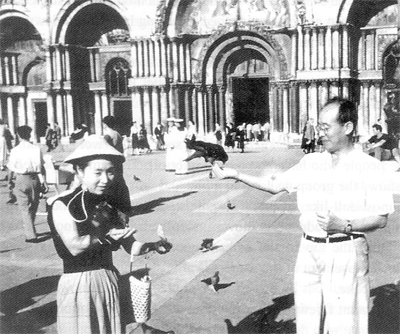

Mizoguchi, age twenty-eight, and Sakai Yoneko at Nikkatsu studio, 1926.

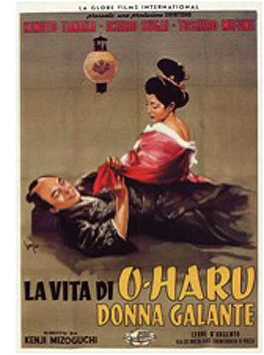

Mizoguchi Kenji’s renown in the West has flowered and faded. Like other Japanese directors, he was unknown in Europe and America before 1950. When Rashomon won the Golden Lion at Venice that year, Japanese cinema sprang onto the world’s radar. Just two years later, Mizoguchi began winning top Venice prizes with Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), and Sansho the Bailiff (1954). His old associate Nagata Masaichi saw export opportunities in Japanese costume pictures, especially after Gate of Hell (1953) won the Academy Award, and so Mizoguchi turned out several historical films with high-tone production values. He died in 1956, after Street of Shame (1956), a return to contemporary social commentary.

In just five years, this flare of attention and the praise of the Cahiers du cinéma critics made him second only to Kurosawa in Western recognition. During the 1960s, while Japanese critics were writing him off as outdated, international critics canonized him. Here’s Andrew Sarris in 1970.

I recently saw an obscure Mizoguchi film at New York’s Museum of Modern Art without any English subtitles, which left me up the Sea of Japan without a paddle. The program notes alerted me to the plot outline, but I was generally puzzled by the personal relationships, and the picture dragged along. . . . And then at the end the beleaguered heroine walks to a restaurant on a hillside overlooking the sea, and she orders something from a waiter in white, and the camera is high overhead, and the morning mists are bubbling all around, and the camera follows the waiter as he walks across the terrace to the restaurant and then follows him back to the heroine’s table now magically, mystically empty. It is as if death had intervened in the interval of two camera movements, to and fro, and the bubbling mists and the puzzled waiter provide the Orphic overtones of the most magical mise-en-scène since the last deathly images of F. W. Murnau’s Tabu.

Mizoguchi’s reputation was based almost completely upon his 1950s work. But as ever, film distribution shaped film tastes. Soon after the 1972 success of Tokyo Story in New York, Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films began circulating many major Japanese titles. Most electrifying for my generation was an abundant set of Ozu films, the arrival of which coincided with Donald Richie’s Ozu (1974). Twenty years after Mizoguchi’s emergence, Ozu began his ascent to the top of the pantheon.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

Talbot’s catalogue included major Mizoguchi titles as well, notably Naniwa Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), Genroku Chushingura (The 47 Ronin, 1941-1942), Women of the Night (1948), and My Love Has Been Burning (1949). These showed us a new Mizoguchi, one that was more pictorially daring and more sharply socially critical, than the one we had known. Soon packaged programs toured by the Japan Film Library Council revealed other films by Mizoguchi and his contemporaries. At a certain point, a Japanese colleague told me at the time, it was easier to see his nation’s prewar films in New York than in Tokyo.

A broader recognition of 1930s-1940s Japanese film was crystallized in the 1978 publication of Noël Burch’s book To the Distant Oberver: Form and Meaning in Japanese Film. Burch urged the case that Ozu, Mizoguchi, and other “mature” directors had done their most ambitious work well before the Western festivals and critics had caught up with them–that in fact the venerated postwar films were mannered and unadventurous compared to the artistically radical prewar work.

Since then, as Ozu (and Naruse, and many more) have risen to the pantheon, Mizoguchi has become quite obscure. Critics haven’t really boosted him much; his most famous film, Ugetsu, ranked 50th in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll. Nor is the range of his work easy to sample on video. In 1976, Kristin and I were obliged to go to London to see the early Ozus not in US distribution; now, everything is on DVD. But many years later I went to Brussels for a complete Mizo retrospective, and the rare titles I saw there remain nearly unknown. His festival classics and the “Talbot canon” circulate on good-quality prints and DVDs, thanks to Criterion and Janus. But other films must be hunted down in obscure foreign DVD.

Worst of all, the survival rate of Mizoguchi’s films is appalling (although not exceptional for Japan). He made 43 films between 1923 and 1929; of these, only one survives complete. For the rest of his career he made or contributed to 42 features, of which we have 30. We lack over half his output. The physical quality of what we have varies a great deal, from gorgeous (Genroku Chushingura) to appalling (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937, blown up from a scratched and contrasty 16mm copy). In fact, copies seem to have deteriorated. Prints I saw in the 1970s of Oyuki the Virgin (1935) were in decent shape, but many copies circulating now seem to be bad dupes of those prints, now much battered. There seems to be no systematic effort to restore what we have.

Tears are easy; tragedy is hard

I can’t deny that Mizoguchi’s fluctuating reputation is due to more than availability. He is easier to admire, even to worship, than to love. His films, though visually sumptuous, can be somber and bleak. Often unremitting tales of suffering, they lack humor (though not irony). Ozu’s mix of poignancy and comedy is much easier to enjoy than Mizoguchi’s forbidding, near-tragic despair. Ozu is also a more rigorous stylist; his signature is in every frame. While Mizoguchi was no less distinctive, he was more pluralistic in his technique.

Another obstacle: despite working with melodramatic material, Mizoguchi cools it down, sometimes to the point of remoteness. For many of his films, the prototype was Japan’s shinpa drama, an early twentieth-century theatrical tradition that blended kabuki themes and situations (e.g., the conflict of love and duty) with Western-style dramaturgy. Shinpa plays tended to concentrate on the sufferings of women in a male-dominated society. Shinpa women are victimized, exploited, and condemned; when they sacrifice themselves for men, too often the men attack them, betray them, or dump them. Mizoguchi worked many variations on these plot elements. When the American Occupation demanded more liberal films from the industry, he simply let the oppressed woman win some victory in the end.

Whether the woman wins or loses, Mizoguchi refuses to beg for tears. Some directors, notably Sirk, amp up melodrama; others, like Preminger, bank the fires. Mizoguchi seems to try to extract the situation’s emotional essence, a purified anguish, that goes beyond sympathy and pity for the characters. In The Poppy (1935), here’s how he renders the moment at which a father and daughter learn that the daughter’s suitor has abandoned her. The core dramatic action is the daughter moving from the foreground to console her father, at which point they embrace.

Some climax! No close-ups, no fast cutting, no camera movement; people withdraw from us and leave us on the outside. All of which suggests that one dimension of Mizoguchi’s artistry consists of exploring how human emotions, notably the unhappier ones, can be expressed in vivid, sometimes surprisingly “cold” pictures.

Pictures tell the story

Everybody grants that Mizoguchi makes magnificent images. He has gone down in history as a pictorialist. But his pictorialism is of a peculiar kind. We tend to think of pictorialist filmmakers as, for instance, masters of landscape, like Ford in My Darling Clementine; or exponents of abstract patterning, like von Sternberg in Shanghai Express; or buccaneers of aggressive depth, like Welles in Citizen Kane.

On each of these possibilities Mizoguchi can match the masters. Here’s a landscape from Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950; this is the scene that made Sarris swoon), a geometrical shot from Hometown (1930), and a bold depth composition from Naniwa Elegy four years before Kane.

It’s not surprising that Mizoguchi relies on the image; in his youth he studied painting (interestingly, Western-style painting at that). But he is, I think, a more fervent pictorialist than his peers.

Most movie scenes consist of a story situation mapped onto the space; the style follows, emphasizes, or shapes the story’s presentation. Suppose, Mizoguchi seems to ask, that we start with an image and ask it to become a drama. That’s in a sense what seems to happen with the Poppy example above: a striking picture develops into a story through a suite of compositional changes. Or consider this, from Sansho the Bailiff. A scene starts with a bundle of brush in a village street. Gradually it becomes the site of action: two children peep out, one by one.

Our view isn’t impeded only by the brush. A man bursts eagerly into the frame, blocking the boy and girl, followed by another man. The camera tracks a bit around the foreground post. As the scene goes on passersby will intrude into the frame.

You can’t, I think, imagine many more ways to suppress our views of the kids. We strain to see past all these obstructions, and when the view finally clears and the children are visible and come forward briefly, they turn from us…and more people pass in the foreground.

This is actually an important moment in Sansho the Bailiff: The children, kidnapped from their mother, are about to become slaves. It could be rendered with all the stops out, as a scene of brutality or high tension, but instead Mizoguchi let the dialogue (after some delay) explain what’s happening. At first you might think that Zushio and Anju have escaped from their captors and are in hiding; the unfolding image initially permits that possibility. Eventually, though, the shot, expressing the children’s fear and shame as they shrink from not only the men but the camera, holds us in its own right.

Instead of an image that is a vehicle for the story, the story is gradually born out of the changing image. To some degree, this happens in many films, but not with the persistence and rigor we find in Mizogcuhi. He talked of wanting to hypnotize the viewer, and this is done, I think, as much by the minute changes in the pictures as by the dynamics of the drama.

This version of pictorialism employs several strategies. I’ll mention just three.

Now you see it, sort of

Kiyonaga Toru, Interior of a Bathhouse (1780s).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Traditional Japanese cinema is itself heavily pictorial, from the zigzag excitement of the 1920s swordplay films to the dynamic modernity of the city dramas and the monumental gravity of historical dramas. Directors, I’ve argued in various places, cultivated a “decorative” approach to technique. Composition, camerawork, cutting, and other tactics often created flashier compositions than we find in other national traditions. As early as 1922, Ikeda Yoshinobu was creating arabesques with a bedstead, framing the faces of grieving family members (Cuckoo).

The gridded zones of the Japanese house seems to have invited filmmakers to explore a sort of Advent-calendar style, with bodies framed in different apertures (The Abe Clan, 1938). The same idea could be applied to a bar’s Art Deco wall divider (First Steps Ashore, 1932).

I’ve also argued that this love of pocketed compositions may be an effort to echo similar impulses in Japanese graphic art. The Kinoyaga woodblock print above, with its partial views of women bathing and the little windows through which we see the male attendant watching, is a beautiful example. Perhaps filmmakers adapted this eye-beguiling tactic as a way of giving cinema some cultural credentials (if not a national identity).

Most directors don’t sustain such flashy compositions. The shots function mostly as long-shots or establishing shots, or as in the Cuckoo example, as a series of brief extracts from the larger scene. Mizoguchi drew upon this decorative tradition but let it be sustained through figures moving into and out of the apertures within the frame. He creates a game of vision, a sort of fluctuating pictorial vividness that conceals or reveals or teases us with information.

One of the most vivid examples comes in this famous scene from Sansho the Bailiff. Tamaki’s leg tendons are cut, and the other enslaved women are forced to witness it. As the struggling Tamaki is peeled away from the wall and the slavemaster walks to her offscreen, the other women become visible and an older master comes slightly forward in the central square Tamaki had occupied.

As she screams, the grid isolates each woman’s fearful turning away. As with the earlier Sansho scene, dialogue comes to “button up” the unfolding of the image: The old man tells the cringing women that all runaways will punished this way.

The impact of the act is amplified not by, say, cutting to different women’s reactions, but by letting us see them all, simultaneously, in a choreography of terror.

Mizoguchi finds an abundant variety of ways to play his game of vision. Not only are figures and faces secreted in various pigeonholes of the frame, but he can tease us with some that are merely shadows or partial figures (The Poppy; Tokyo March, 1929). Sometimes the key element, such as a character’s reaction, is obscured by a semi-transparent surface, as when the embarrassed model is caught in a corner of a screen in Utamaro and His Five Women (1946).

What other directors treated as piquant flourishes, imaginative ways to arouse our visual interest before moving in to closer views, Mizoguchi saw as a way to activate any cranny of the image and invest it with expression. But for that process to unfold, he needed time.

Intensify and prolong

From the brief surviving fragment of Tojin Okichi (1930).

During the course of filming a scene, if an increased psychological sympathy begins to develop, I cannot cut into this without regret. I try rather to intensify and prolong the scene as long as possible.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Mizoguchi is famous as an exponent of long-take shooting. His earliest surviving film, Song of Home (1925) displays the Hollywood-style editing that most Japanese filmmakers mastered at the period. At some point–he says it was while shooting Tojin Okichi (Okichi, Mistress of a Foreigner)–he began using a method he called “one scene, one cut.” (Here “cut” apparently refers not to a shot change but to a single take, like a “cut” of meat. Hollywood filmmakers talked the same way sometimes.) That would suggest that he took every scene in a single shot, but actually he didn’t. Most of his scenes are built out of several shots, and throughout his career he would have recourse to standard analytical and shot/reverse-shot cutting for many sequences. He wasn’t as strict about the plan-sequence as, say, the Miklós Jancsó of the 1960s and 1970s was.

Still, he definitely used longer takes than most filmmakers of his day. The shots in most of his post-1935 films average between twenty-five and forty seconds in length, which means that some shots run minutes. Many of his long takes are made from static camera positions, as in the above examples. But he didn’t shrink from camera movements, either tracking shots or crane shots. Kristin and I discuss an example from Sisters of Gion in Film Art, and in his later films he enjoyed establishing a setting with a high-angle crane shot before moving in to details. He also enjoyed riding the crane and directed from it even if the shot was static.

Fixed frame or moving shot, Mizoguchi’s long takes can extract an arc of pictorial-dramatic intensity. That arc can have a clear-cut ABA pattern. In My Love Has Been Burning, the liberal feminist Eiko finds her weak lover Hayase drunk and despondent. He’s no longer the idealist she thought he was, but he defends himself as changing with the times.

Hayase says he’s got some money now and they can marry. When she doesn’t warm to the idea, he attacks her, and suddenly her face gets enlarged, upside down, when he slams her to the floor. This is the first high point of the scene.

They struggle out of frame, but Mizoguchi doesn’t follow them.

Immediately there’s a second assault on our vision: a screen abruptly crashes into the foreground.

After it settles into place, Eiko flees back into the frame, pausing by the doorway. She leaves, and Hayase totters to the same spot looking after her.

The shot has built up to one spike, the image of Eiko on her back, her face close to us, and then to a second, with the collapsing screen. At the end, the site of action returns to the beginning: a figure near the doorway, something else (Hayase, the screen) in the foreground. But in the course of this ABA pattern, the game of vision has concealed as much as it has revealed.

Throughout his career Mizoguchi experimented with the patterning of his long takes, often building them around advances to and away from the foreground, as in these examples. This tactic can be seen in a pure state in the most intense scene of the Occupation feminist film Victory of Women (1946). Here the characters rush the camera and shrink from it as the emotional pitch rises.

Tomo’s husband has just died, and she has already told her friend the lawyer Hiroko that she has no more milk for her baby. Tomo calls on Hiroko, who invites her to come in. The camera obediently tracks back as she enters and sits.

Hiroko, at first oblivious to the distraught Tomo, begins to question her. At first Tomo says that nothing has happened to her baby, and she slides away from Hiroko. She tells her that her husband died the day that they had met in the street. She edges closer to the camera.

Sobbing, she tells Hiroko that the baby is dead; he died sucking her breast. She falls out of the frame and as the camera pulls back Hiroko bends to comfort her. But she also asks Tomo to tell her exactly what happened.

Tomo confesses that staring at her crying baby, she hugged it so close that she may have killed it. As she rises, she cries, “My baby!” And she turns and staggers, like Ayako in Naniwa Elegy, to the most distant point of the set–as if hoping to escape both Hiroko and the camera.

Track in as Hiroko goes back to her, at the spot at which the shot’s action started. Once more the two women advance to the camera, with Hiroko nearly dragging Tomo back to the center. But when Hiroko suggests she go to the police, Tomo slides quickly away from her, back to us, and the camera abruptly pulls back to accommodate her. As when the paper wall crashes into the frame in My Love Has Been Burning, a spike in the drama is accompanied by a second burst into the foreground.

Hiroko rushes to embrace Tomo, assuring her that “You must not run from life, but face it!” Mizoguchi’s staging favors the doubt and fear on the face of Tomo, not the somewhat complacent Hiroko.

As Hiroko hurries off to dress for going out, Mizoguchi’s camera lingers on Tomo, not only pitiable but justifiably worried that she is condemned. As she bends and glances to and fro, Mizoguchi ends the seven-minute scene on an image of a woman with nowhere to turn. This is a terrifying final image: Is this what Hiroko meant by “facing life”?

Some of Mizoguchi’s earlier works go further still. Instead of a coming-and-going pattern, in which the characters confront the camera and then retreat, we get a going-and-going one. The most famous, about which I’ve written probably more than I should, comes in Naniwa Elegy, when Ayako, telling her boyfriend of her sexual infidelity, retreats from him, and from us.

A Western director–Wyler, say, as in The Little Foxes, or Huston–would have put the camera at exactly the opposite point, in the corner of the wall, so that Ayako would advance toward us and Nishimura’s reaction would be constantly visible in the background. It’s as if Mizoguchi anticipated such full-disclosure framing (before these men had even made their films!) and dismissed it as too easy. By suppressing characters’ expressions, he throws our attention onto Ayako’s voice and her posture, while also sustaining some suspense about how Nishimura will respond to her revelations.

Mizoguchi finds a huge variety of ways of turning images into drama, and he has left us a rich repertory of staging strategies–if we only look. Young filmmakers, are you looking?

Filigree

Tanaka Kinuyo and Mizoguchi Kenji in Venice, early 1950s.

[The long take] allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.

Mizoguchi Kenji

Once Mizoguchi enhances the decorative frame with surfaces and holes bristling with possibilities, and once he sustains it in time through the long take, he can build his scenes out of slight changes in the image–changes that add nuance and expressive depth to the drama. We’ve seen this already in several passages, but I want now to stress how this sharpens our attention and engagement. The restraint of Mizoguchi’s handling (restraint within sumptuousness, I should say) trains us to watch for the tiniest shift in pictorial emphasis. This is the third strategy I want to mention.

In Lady of Musashino (1951), minor changes around the deathbed drive our eye to the profile of the dying Michiko.

Likewise, when Oishi in Genroku Chushingura reads the master’s poem, sent to his vassals after his suicide, he lowers the paper just a little at the climax, and the gesture is echoed in the men’s slumping forward even more. (This is a movie largely made of just-noticeable differences.)

The just-noticeable differences can be triggered by tiny changes in the avenues of our vision. In Street of Shame, the brothel owner, turned from us in the middle ground, first reveals Mickey and the delivery boy down the left corridor. When he shifts his head, Mizoguchi closes off that view and allows faces and bodies of the prostitutes to fill up the corridor on the right.

Bolder movements can yield even briefer glimpses. When Oharu reads the message from her dead lover, Mizoguchi gives us a “decoy” shot: Her mother stands guard on the left and in the distance we see the door through which the father is expected to come. But the scene’s real action is taking place behind the hanging kimono, where Oharu reacts painfully to the letter. Since we can’t see her, only her wavering voice and the trembling of the kimono convey her emotion. Suddenly she starts to thrash around, her mother leaps toward her, and a tussle ensues. The kimono is pulled down in a heap.

What’s all the fuss? What is Oharu doing? The answer is given to us in an almost subliminal detail, the knife that flashes through the lower right corner of the shot in only two frames on the 35mm print. Oharu races out of the shot, bent on suicide.

So the nuances that spring up may be protracted or simply glimpsed, but either way they become the product of the image giving birth, through its transformations, to the drama. The strategy is just as applicable to closer views as to long shots. In one scene of Woman of Rumor (1954), the keeper of an elegant brothel notices a young man getting cozy with her daughter. The tension is exacerbated by the fact that she hopes to nab Dr. Hatoba herself. As the two talk, Mizoguchi buries Hatsuko in the rear of the scene, her presence signaled by a shadow and her kimono sleeve poking out from a screen.

Mizoguchi cuts directly in and provides a medium-shot of Hatsuko peeking. This might seem safe and conventional, especially in the light of daring choices like those made in Naniwa Elegy. But Mizoguchi now wants to trigger the game of vision around the woman’s face and the edge of the screen. As she listens, he teases us with a little suite of changing expressions and minute gradations of partial blockage–a sort of pictorial vibrato.

As Hatsuko edges out to approach the couple, Mizoguchi switches our attention to small, nervous hand gestures.

Once installed behind the couple, Hatsuko starts the whole process again, from eye-catching sleeves to peekaboo eavesdropping.

Mizoguchi was a fairly pluralistic filmmaker, so the strategies I’ve itemized don’t exhaust everything we encounter in his movies. Sometimes he builds scenes in a fairly orthodox way, with traditional framing and cutting. But taken as a whole, his films offer a magnificent repertory of ways in which the image can, under pressure, deepen and enrich a dramatic situation. Unlike most of today’s filmmakers, he cares about rigor, nuance, and austerity–while at the same time working with scenes of intense emotion. Admire him, worship him, love him, or just respect him: film culture can’t live fully without him.

Thanks, over forty years of viewing, to the Japan Society of New York, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute (formerly the Japan Film Library Council), Dan Talbot and José Lopez of New Yorker Films, and the Brussels Cinematek, especially Gabrielle Claes.

The MoMI series runs until 8 June. It begins on 16 May at the Harvard Film Archive and on 19 June at Pacific Film Archive. For Fandor’s Keyframe daily, David Hudson has a varied roundup of response to MoMI’s series.

Both Criterion and Masters of Cinema offer many Mizoguchi films on DVD, some on Blu-ray. See also Criterion’s Hulu Plus offerings. Digital Meme sells DVDs of some early Mizoguchis, with benshi accompaniment; the exasperatingly brief fragment of Tojin Okichi is on volume 2..

My quotation from Andrew Sarris comes from “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1970,” in The Primal Screen (1973), 60-61.

Good clichés will never die as long as journalists need to crank out copy. The MoMI retrospective has revived the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi tug-of-war, this time among New York critics (here and here). Such sideswipe critiques and hosannas can’t really be backed up within the space limits of popular publishing. Moreover, I think that such quick assertions of taste block close consideration of the work. Once you’ve dismissed a filmmaker, you’re unlikely to probe further, and your readers will probably be even less curious. I defected years ago from the Kurosawa-Mizoguchi skirmishes.

The fact that every decade or so Mizoguchi is “rediscovered” through a retrospective indicates his elusive reputation. Among English-language scholars, the 1980s was the big period. Dudley Andrew wrote a still indispensable reference book on Mizoguchi in 1981, and Keiko McDonald offered a penetrating critical survey in 1984. Both volumes, now rare and costly, deserve to be made available in digital editions. Robert Cohen’s two-volume dissertation “Textual Poetics in the Films of Kenji Mizoguchi” (UCLA, 1983) was also significant. Since then, incredibly, we have had only one more overview in English, Mark Le Fanu’s Mizoguchi and Japan, along with an in-depth analysis of some 1930s films, Don Kirihara’s award-winning Patterns of Time. Sato Tadao’s monograph was published in Japanese in 1982, but it’s only recently been available in (a somewhat problematic) English translation (as Kenji Mizoguchi and the Art of Japanese Cinema). Two of my stills are drawn from this book. The French have been more consistently productive, with several studies over the years. A thorough account in Spanish is by the prolific Antonio Santos.

For some background on Western rankings of Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, and Ozu, see this interview with the late Hiroko Govaers. Hiroko was instrumental in bringing many classic Japanese films to Europe and the U.S.

Some of the material in today’s entry comes from Chapter 3, “Mizoguchi, or Modulation,” of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. That offers a much fuller account of what I think Mizoguchi is up to, although today’s blog offers some points and examples not in the chapter. Offshoots of the book’s argument can be found in this online update, and in this blog entry, which compares Mizoguchi with his sort-of-rival Wyler. My oldest piece on the director, “Mizoguchi and the Evolution of Film Language,” in Stephen Heath and Patricia Mellencamp, eds., Cinema and Language (1983), 107–117, contrasts his work with Western practitioners of deep-space staging. Background on the “decorative” impulses in traditional Japanese cinema can be found in Essays 12 and 13 in my Poetics of Cinema, and in early portions of Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema.

P. S. 29 June: Thanks to Jeff Fort for correction of a title in the original blog post!

Sansho the Bailiff.

HKIFF: Firebirds soar and MOTHER returns

Firebird Young Cinema Award winners and jury members, Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2014. For photos of all winners and jurors, go here.

DB here:

As my Hong Kong trip nears its end, I realize I’ve been too busy to blog properly. So when the wobbly net connections in my hotel permit, I’ll offer some quick entries on things I’ve seen and done.

Prizing movies

First, the big news. The festival hosts several annual awards. There are prizes from SIGNIS, the World Catholic Association for Communication, and FIPRESCI, the International Federation of Film Critics. The festival has established its own prizes as well: for best documentary, best short film, and for young filmmakers. The complete list of winners is here.

The jury for the Firebird Young Cinema Competition consisted of Bong Joon-ho, Karena Lam Ka Yan, Christopher Lambert, and me. We faced some hard choices, but we finally settled on three winners.

Special Mention went to Forma, by Ayumi Sakamoto. It’s a slow-burning thriller shot in mostly distant long takes and displaying a backward-looping time scheme that makes you rethink the first half. It also displays one virtue of video production: its crucial scene consists of a single shot, only apparently haphazardly composed, that lasts over 22 minutes!

We gave the Jury Prize to Tsuto Tetsuichiro’s Tale of Iya. It’s an extraordinarily ambitious film shot in 35mm Scope in a great variety of locales and weather conditions. It’s about the rigors of rural life, the need for ecological understanding, and a young woman’s growing awareness of her duties to her past. Some scenes recalled the great Japanese widescreen films of the 1950s and 1960s.

The top prize, the Firebird Award, went to Macondo, a very assured job of storytelling from Sudabeh Mortezai. The plot concerns Chechen refugees in Vienna struggling to get asylum status. At the film’s center is the remarkable performance of Ramasan Minkailov as a shrewd boy who has lost his father in the Chechin war. It’s a coming-of-age film, I suppose, but it also touches on issues of responsibility and loyalty without moralizing.

Serving on the jury was a treat for me, and I learned a lot from talking with my fellow jurors. Karena is famous for her roles in July Rhapsody and Inner Senses. More recently she has published Voyages, a remarkable book of Polaroid photographs. Christopher, as both actor and producer, has several new projects, including Electric Slide, coming to Tribeca. Joon-ho’s Snowpiercer will be released on 27 June in the US; after prolonged wrangling with Harvey Weinstein, this will be the director’s cut. The release will be limited, but it will pass to VOD thereafter.

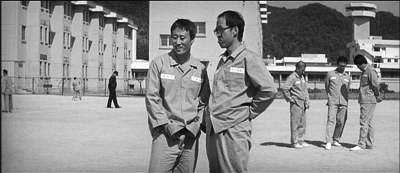

Black and white is the new black

While finishing Snowpiercer, Bong took on a pretty intriguing side project. He told his cinematographer, Hong Kyung-pyo, that he’d always wanted to make a black-and-white film but that no producers would finance one nowadays. Hong suggested that they remake Mother (2009) in black-and-white. So during postproduction on the big film, they used spare days to redo the color data from the older one. It wasn’t simply a matter of hitting a button. They performed color correction shot by shot so as to control the exact degree of tonality and contrast.

The result, already released on Blu-ray in South Korea and world-premiered at Mar del Plata, had its Asian premiere here in Hong Kong. It is exactly the same film, but without full color. Punning aside, it really does become more of a film noir–harsher, bleaker, and more somber.

The original film has a fairly muted palette, with lots of grays, beiges, soft blues, and earthy browns. In black and white you lose the nicely distinguished grayish-blues of a shot like this. (My monochrome frames are rough approximations derived from Photoshopping the color DVD; I don’t yet have the Blu-ray.)

At the same time, the performances seem more highlighted in the new version. Bong noted that certain colors, such as the green on the golf course, were a little opulent in the original. In the new version they don’t overwhelm the characters, and the abstract elements of the composition become a bit more apparent.

Bong also observed that some viewers have said that the characters’ eyes—pure black—are more prominent in black and white. I had never thought about it, but in old films the actors’ gazes do seem more gripping. At times, the mother’s face becomes more haunted, and haunting.

Just as striking, a clue (I’d hate to call it a red herring) depends on a crimson smear on a golf club. Rendered in black-and-white it becomes even more ambivalent.

Bong said in the Q & A that the project satisfied an urge he discovered while watching Nosferatu at an archive screening without any music. “It was a very purified experience.” He wondered if he could go back to “a very pure state of film, like a salmon swimming upstream.” Yet the new version still harbors one visual surprise.

The monochroming of Mother seems to me a rewarding experiment; I look forward to comparing the two versions and seeing how each can suggest different sides of a scene or summon up different expressive qualities. At the moment, I prefer the black-and-white version, and Bong suggested that he was starting to do the same. After Nebraska and Mother, maybe filmmakers will rediscover what black-and-white can do—and producers and audiences will let them.

Forma (2013).

Watch again! Look well! Look! (For Ozu)

Okada Mariko and Tsukasa Yoko with Ozu, on the set of Late Autumn (1960).

DB here:

Ozu was born on 12 December (in 1903) and died on 12 December (in 1963). He has been gone fifty years, yet his films are as fresh, inviting, funny, and moving as ever. As chance would have it, my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema was published twenty-five years ago. Two events of the past few months have brought me back to him.

First, my biannual summer course in Antwerp, held under the auspices of the Flemish Film Foundation, was focused on him. As I’ve explained in earlier years (2011, 2009, 2007), at this Summer Movie Camp, across a week we immerse ourselves in films and wrap lectures around them. It was a joy to see a dozen of his films, mostly in good 35mm prints. Our sessions provided an occasion for me to rethink some things I said in the book, as well as to notice more about how these dazzling, apparently simple films work and work upon us. I learned as well from the comments and questions of many of the participants. The whole experience didn’t shift my opinion, stated on an earlier Ozu anniversary, that “no director has come closer to perfection.”

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

As the title indicates, it’s centrally about Ozu’s continuing influence on modern cinema. I was asked to contribute a preface, which Diane and Mathias have kindly allowed me to reproduce below in revised form. I’m now chiefly aware of what I neglected (no mention of Wenders’ Tokyo-Ga) and didn’t know about (for instance, Claire Denis’ admiration for Ozu). These and many other matters are taken up by the book’s contributors. But I think my piece may be of interest as a small update of my Ozu book.

In 1988, most of Ozu’s surviving films weren’t easy to access. Things have changed. And since I wrote the essay, virtually all the extant work has appeared on DVD, on cable television, and in the Criterion collection on Hulu Plus. As his films become more and more familiar, we can expect ever-greater acknowledgment of his centrality. Already, the 2012 Sight and Sound poll of critics put Tokyo Story just below Vertigo and Citizen Kane; the directors’ poll put it at the very top.

Why not watch an Ozu film today? Go beyond Tokyo Story, fine as it is, to Early Summer, Passing Fancy, Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, An Autumn Afternoon, The Only Son, The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, Ohayo, Diary of a Tenement Gentleman, What Did the Lady Forget?, Dragnet Girl, Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?, I Was Born, But… and on and on.

Catching up with Ozu

Ozu is a major presence in today’s international film culture. When I began seeing his work in the early 1970s, about half a dozen Ozu movies were in circulation, and of those only Tokyo Story was known to nonspecialist cinephiles. As late as the 1980s, I had to travel to archives in Europe and the US to see his rarer films. Now even the most obscure early 1930s titles are issued on DVD, and the films have been widely distributed in touring packages. They are screened all over the world, a process lovingly recorded on Twitter. Ozu is better known to a broad public than Mizoguchi Kenji is—an ironic turn of affairs, given that in many countries Mizoguchi gained fame during the 1950s and 1960s, when Ozu was unknown.

Even more famous throughout the west was, of course, Kurosawa Akira. His influence on mainstream cinema has been robust and pervasive. If slow-motion violence has become a convention in American films since Bonnie and Clyde, that is directly traceable to the director of Seven Samurai. The use of very long lenses to cover a scene, common in American cinema of the 1960s and thereafter, owes a great deal to Kurosawa’s strategies in films like I Live in Fear and Red Beard. Editing on the camera axis for visceral impact, a Kurosawa signature technique, has bumped up the visual excitement in many American action pictures.

Ozu has not had such a direct influence. He is much less easy to assimilate. With few exceptions, his signature style has been far less imitated, and it has even been misunderstood. His effect on modern cinema, it seems to me, has been far more oblique, with directors paying him tribute in discreet, sometimes unexpected ways.

Brand Ozu

Ozu wing, Kamakura Cinema World, 1996.

Ozu was careful to mark his uniqueness. He designed his films to be sharply different from those of his contemporaries. His home base, the Shochiku studio, encouraged directors to develop personal styles, and he was allowed to make artistic choices that could only be considered eccentric. At first glance, Ozu’s films may seem to melt into a broader idea of “Japanese artistic culture,” but the more films we see by his colleagues, the more idiosyncratic his works look.

Having allowed Ozu to make such singular films, Shochiku has exacted a reciprocal obligation: his legacy now serves as a trademark for a film studio. For the world at large, Japanese cinema consists of Kurosawa and Toho studios’ Godzilla, Nikkatsu action, and anime. Shochiku had its tradition of modest, humane dramas of working-class and middle-class people, treated with that mixture of humor and tears known as the “Kamata flavor” (after the Tokyo suburb where the studio was located). That tradition was sustained by Ozu and his colleagues through the 1950s as a brand identity. The forty-eight Tora-san films (Otoko wa tsurai yo, “It’s Tough to Be a Man”) became what we’d call a frachise for Shochiku from 1969 through 1996.

But as media became globalized, and as merchandising became central to sustaining filmmaking, Shochiku’s product came to seem narrowly local. Accordingly, the firm turned its attention to its most famous employee. Shochiku’s familiar postwar logo, a view of Mount Fuji, had become for westerners part of Ozu’s iconography.

Now Shochiku tried to reclaim its trademark by reminding viewers that he belonged to a bigger family.

For the local market, Shochiku tried a bit of merchandising, such as phone cards with scenes from Ozu movies. More ambitiously, there was Shochiku Kamakura Cinema World, a theme park established in 1995 at a cost of $125 million. It held many attractions devoted to American cinema, and it even allowed customers to visit a movie in the making, but one wing was devoted to Shochiku’s legacy properties, including a replica of a street from the Tora-san series. There were as well Ozu memorabilia, including a three-dimensional tableau of an effigy Ozu directing a scene in Tokyo Story. The adjacent vitrine housed a reconstruction of his work area at home, complete with whisky bottle and bright red rice kettle.

Cinema World closed in 1998, a financial failure. But Shochiku persisted and declared in 2003 that it would host a worldwide celebration of Ozu’s hundredth anniversary. That celebration consisted of a new touring program of 35mm prints of his films, with ancillary ceremonies and festival activities, and several new DVD releases. Shochiku went further and commissioned Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière, a film in homage to the great director. For festivals and arthouse cinemas, Hou’s tribute was aimed to recall Ozu’s greatness and, by association, Shochiku’s place in film history.

As directors have sought to retain the Kamata flavor in later decades, we find hints and traces of Ozu as well. A film like 119: Quiet Days of the Firemen (1994), in which middle-aged men in a small village fantasize about romance with a young researcher, might bring to mind the overactive imaginations of the grown-up schoolboys of Late Autumn (1960). Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Still Walking (Aruitemo aruitemo, 2008) is a family drama made in full awareness of the Ozu tradition. Not surprisingly, Yamada Yoji, impresario of Tora-san, has invoked the Shochiku tradition in several productions (notably Kabei: Our Mother, 2008, and Ototo, 2010). At the start of 2013 Yamada, at 81 years of age, released an updated remake of Tokyo Story.

Ozu comes to America

Days of Youth (1929).

Since at least the early 1920s, the Japanese cinema has responding to the American cinema. During the classic period, American films did not dominate the Japanese market, as they did in many other countries, but filmmakers were nevertheless acutely conscious of Hollywood. In particular, the founding of Shochiku in 1920, with a self-consciously modernizing orientation under Kido Shiro, created a ferment that changed Japanese cinema forever.

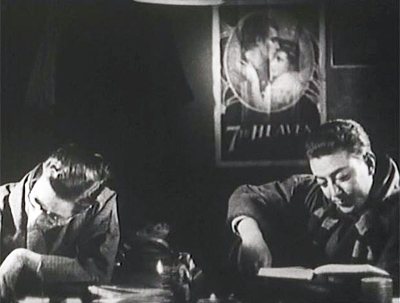

Like other Kamata/ Ofuna directors, Ozu relied crucially on American cinema. There are visual citations (the Seventh Heaven poster in Days of Youth), lines of dialogue about Gary Cooper and Katharine Hepburn, borrowed gags (from A Sailor-Made Man in Days of Youth), and even an extract from If I Had a Million in Woman of Tokyo. More deeply, his early films absorbed the analytical editing of 1920s Hollywood. He broke every scene into a stream of precise, slightly varied bits of information in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd.

Ozu paid American cinema a deeper tribute. Having grasped that system of axis-of-action continuity that Hollywood had forged from the late 1910s, he created his own system as an alternative. Instead of a 180-degree organization of space, he proposed a 360-degree one. This allowed him to absorb the Americans’ innovations and yet give them a new force. Cuts would use eyelines, shoulders, and character orientation, but would often show characters looking in the same direction, their figures and faces matched pictorially from shot to shot.

A cut on movement could be made by crossing what American directors called “the line.”

Further, Ozu realized that the establishing shot, that depiction of the overall space of the action, could be prolonged and split into several shots. The result was a suite of changing spaces that could be unified by shape, texture, light, or even analogy (one window/ another window). These transitional sequences substitute for fades and dissolves, turning ordinary locales into something at once evocative and rigorous.

All of these transformations of Hollywood’s stylistic schemata are rendered more palpable by a single, simple choice that is more single-minded than anything to be found in Hollywood: The camera is typically placed lower than its subject. This constant framing choice acts as a sort of basso continuo for the melodic variations Ozu will work on two-dimensional composition and three-dimensional staging.

This entire stylistic machine might seem to be aimed wholly at working out its own intricate patterns, and indeed to some extent that is what happens. The aficionado can appreciate the refinements, the theme-and-variants structuring, created by Ozu’s cinematic narration. There’s playfulness as well; how funny, he seems to say, that editing and composition can play hide-go-seek with quilts and ketchup bottles. Just as important, all these techniques nudge us to arouse our attention—to the possibilities of cinema, but also to the shapes and surfaces of the world as they change. Alongside the characters’ drama is a realm at once stable and ceaselessly shifting; the characters and their drama are subject to the same forces of mutability. Ozu’s modest pyrotechnics activate the world his characters inhabit, subject them and their actions to the same suite of transformations, and have the larger purpose of reawakening us to our world.

Made in USA

As Ozu’s films became known in the west, citation-happy directors of the 1980s took notice. An example is the moment in Stranger Than Paradise (1984, above), when Eddie reads off the list of horses running in the second race: “Indian Giver, Face the Music, Inside Dope, Off the Wall, Cat Fight, Late Spring, Passing Fancy, and Tokyo Story.” After a pause, Eddie says to bet on Tokyo Story. We know from Jarmusch’s account of visiting Ozu’s grave that he was a passionate admirer, but his films seem to me to show his debts chiefly in their “minimalist” approach to their action.

More elaborately, Wayne Wang offers a self-conscious homage in Dim Sum (1985). This story of a widow, her brother-in-law, and her daughter transfers an Ozu situation to San Francisco and a Chinese-American community. Should the daughter marry and leave her mother alone? The uncle, who runs a declining bar, urges the girl to do so. The situation, he says, reminds him of “an old Japanese movie” in which a parent urges the child to start a family. As in Ozu, the generations are sometimes captured in “similar-position” (sojikei) compositions.

To the generational split of the Ozu prototype, Wang adds the cultural division between modern America, the daughter’s home, and Hong Kong, home not only to the mother but all the friends in her age group. The generational contrasts would be elaborated upon in Wang’s later Joy Luck Club (1993), which counterpoints the experience of four mothers and four daughters.

Well aware of the Ozu parallels in the plot, Wang elaborates them through some stylistic choices. The film starts with a static thirty-second shot of curtains blowing alongside a sewing machine. The mother comes into the frame, pours tea, takes pills, and starts the machine. The next sequence consists of isolated details—a birdcage, a table.

Only then do we get a placing shot of the street, but it serves here as a transition taking us out of the home (Ozu would probably have included part of the window frame), then to San Francisco Bay and then to a young woman seen from the rear sitting on shore.

No drama is forthcoming–no conversation, not even a voice-over suggesting the young woman’s thoughts. The lyrical capstone of the sequence comes with a nearly abstract shot of the water, perhaps the woman’s point of view, but unaccompanied by language or music.

Wang has given us an imagistic preview of details to be seen later. Not only will we come to recognize the young woman as the daughter Laureen, but we’ll see the household furnishings, street locations, and bridge views at various points in the film.

The rest of the film is not as disjunctive as this opening, and Wang soon settles into the sort of loose, leisurely plotting that characterized independent film of the period. But the objects and cityscapes we see don’t become dramatically significant; they are part of the ambience of the characters, somewhat in the Ozu manner. But neither do they take on the elaborate variations and minute adjustments we find in Ozu’s “hypersituated” objects and recurring locations. Still, of all American directors Wang has most willingly adapted Ozu’s aesthetic to his own personal concerns, while paying homage to a director who was just starting to be appreciated as both storyteller and stylist.

Otherwise, the balance-sheet seems to me virtually empty. Every young American filmmaker seems to have studied Kurosawa, but which of them knows Ozu—or, like Eddie, have bet only on Tokyo Story? Filmmakers elsewhere have been more generous and discerning.

Citation, pastiche, and parody

Hou Hsiao-hsien, no cinephile in his youth, came to admire Ozu later in life, and he used citation in a more thoroughgoing way than Jarmusch had in Stranger than Paradise. Liang Ching, the modern-day protagonist of Good Men, Good Women (1995), leads a sort of parallel life with a Taiwanese woman she’s playing in a film: Chiang Bi-yu, along with her husband, who joined the anti-Japanese resistance on the mainland in 1940. But the parallel is a contrast as well, since Liang is unhappy in her love relationships and seems to lack any sense of social commitment. Her drifting, rather lost style of living is counterpointed not only to the courageous and energetic Chiang but also, via a televised movie, to Ozu’s postwar world.

Early in the film, Liang is awakened by the beeping of her fax machine. As she droops at her kitchen table, her television monitor runs the bicycling sequence from Late Spring (1948).

These cheerful shots of Noriko and Hattori on an outing provide yet another contrast to Liang’s brooding torpor about the death of her lover Ah-wei. They also suggest another way to be a heroine, quietly strong and capable of both love and defiance. And the chaste outing we see in Late Spring contrasts sharply with the intense eroticism of the flashback that follows this morning scene, showing Liang and her lover caressing each other before a mirror. Unlike Ozu’s couple, they need a narcissistic magnification of their passion. If Good Men, Good Women’s overall plot condemns the Japanese for their army’s invasion of China, Hou from the start reminds the audience of another Japan, one that after the war became, at least in Ozu’s hands, a place of humane feeling. This is no one-off joke as in Jarmusch’s citations; the Late Spring extract deepens the thematic reverberations of Hou’s film as whole.

Likewise, instead of the sporadic invocations of Ozu’s style provided by Wayne Wang, the early films of Suo Masayuki show more engagement with the Ozu manner—particularly because they are turned to comic ends. Suo’s first feature, My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family (Hentai kazoku: Aniki no yomeson, 1984) was a curiosity: a softcore pornographic film shot in a distinctly Ozuian style. Only in Japan can an erotic film spare the energy to borrow so explicitly from a master of the cinema. While the newly married couple has thumping intercourse upstairs, the husband’s father, sister, and brother sit calmly downstairs, sighing or frowning slightly in response to the gymnastics overhead. One evening the father comes home from a drinking bout and the son, like the son in An Autumn Afternoon, warns him to cut back.

Suo gives us the father sitting alone in an Ozuesque shot, and as his head slumps, Suo cuts to the wife upstairs, rolling her head forward in a similar gesture.

True to the exhaustive geometry of pornography, the brother graduates to sadomasochism, the adolescent son becomes fixated on his sister-in-law, and the young daughter takes up work in a “soapland” parlor. Thus is the Ozu family drama turned upside down, with the father observing everything with a bemused, helpless smile. Suo, who had studied film under Hasumi Shiguéhiko, turned in a well-crafted film that was a virtual parody of the late Ozu style. Of course, by the time he started, Suo was able to study video releases and mimic the Ozu look shot by shot.

In Suo’s next films, parody turned into pastiche. Fancy Dance (Fanshi dansu, 1989) and Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (Shiko funjatta, 1992) display a fanatically precise understanding of Ozu’s unique use of space. Suo adheres to the low camera height, builds scenes out of slightly overlapping zones, and avoids camera movement. He indulges in the master’s penchant for head-on shots that can be matched graphically across a cut, leaving us to notice the variations of color and texture within remarkably similar compositions.

Suo will even follow Ozu’s penchant for graphically matched movement across cuts. His sumo opponents spread their arms in a continuous movement as smooth as that displayed by Ozu’s drinking buddies.

Westerners often ignore Ozu’s penchant for social comedy in the Lubitsch vein, but Suo’s films happily explore this dimension. American and European filmmakers seem aware only of Ozu’s postwar films, but Suo the cinephile grasped that the 1930s college comedies offered fertile resources. Suo’s youth pictures show young people giving up modern popular culture in favor of Japanese traditions that are so old that they become fashionably retro. In Sumo Do..., a ragged college sumo team discovers that the sport turns them from slackers into adepts. In Fancy Dance, a talentless rocker, forced to live in the Buddhist monastery he has inherited, eventually learns that Zen can be cool.

Shall We Dance? (1996) modifies the Ozu look into something more generically Kamata-toned, but Suo still shows traces of the master’s rigor. For example, the first time that the camera moves is when the bored executive takes his first tentative lesson in ballroom dance. The film’s social critique is not as harsh as that in Ozu’s 1930s work, but it does dramatize the stifling limits put on both the salaryman and his family.

Just-noticeable differences

Five Dedicated to Ozu.

The two most famous Ozu homages, both from his anniversary year of 2003, are more puzzling. For neither Hou’s Café Lumière nor Abbas Kiarostami’s Five Dedicated to Ozu can be easily categorized as citation, assimilation, or pastiche. How have these two masters paid tribute to him?