Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Donald Richie

Donald Richie and students. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

DB here:

He died last week, aged 88.

What was his life about? The public dimensions involved, of course, his status as unofficial spokesman, principal gaijin, the gatekeeper and guide to anyone interested in Japan. He hosted grad students as genially as he played tour guide to Truman Capote and Susan Sontag and Jim Jarmusch. I don’t know of any other situation in which an American (from Lima, Ohio, no less) became the spokesperson for a foreign culture. From the 1950s into the 2010s, in a stream of writings and lectures, he interpreted how the Japanese lived, worked, thought, and created. Although he wrote about everything from landscape to tattoos, he became best known as the supreme expert on Japanese cinema. His particular love was the postwar “Golden Age” of the late 1940s through the early 1960s.

Tokyo/Hibiya crossing; Dai-Ichi Building, 1947.

Japan was still terra incognita to Westerners when he came there in 1947. When the outer world demanded to understand this very strange place that had fought so tenaciously against America, there arose a generation of interpreters. Of that cadre, though, he stands out as the man you can’t quite place.

The oldest of the group was Edwin Reischauer, who worked largely in international policy. A somewhat younger man, Donald Keene, became the dean of Japanese literary studies. Keene has provided translations and magisterial overviews of the Japanese novel, drama, and poetry. An almost exact contemporary of Keene’s is Edward Seidensticker, who has been a renowned translator and cultural historian.

Only a little younger was our author, who came to Japan in the Navy and soon became a prolific writer. Yet his work didn’t fit the mold of the other American experts on Japan. He was neither a traditional scholar (he read little Japanese, though he spoke it fluently) nor a pure journalist (he refused to be tied to topicality). He remained resolutely in-between. What academic would have the brass to sum up “The Japanese Way of Seeing” in a seven-page essay? Yet what journalist would write subtle critical monographs on Ozu and Kurosawa?

In my copy of Partial Views: Essays on Contemporary Japan, he wrote: “For David, from Donald, particularly pp. 157-205.” On those pages you find his “Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura.” It’s a fertile survey of recurring themes and techniques in Imamura’s films. In the hands of a professor it could certainly become a tightly argued book. Was his inscription telling me that, when he wanted to, he could execute criticism with an academic accent? If so, it was unnecessary. I didn’t need convincing. I think he could have done whatever he wanted.

What he wanted, I think, was to join the tradition of European belles lettres. He earned his living by writing, and doubtless his championship typing skills steered him toward the quick turnover of daily deadlines. More deeply, I think, he found the shorter piece suited his flair for precise evocation. Even in his books, his approach is essayistic, faceted. His tone—thoughtful but not severe, conversational, projecting wide knowledge and good sense and humane modesty—won the reader by its quiet conviction that the subject was important. This essay wouldn’t be the last word; indeed, he would likely return to the subject years later, testing out new ideas. Much of his output consists of occasion-based pieces, and any of these might be recast, cut, or expanded. A craftsman knows how to recycle scraps and spruce up old projects.

This commitment to fluent reflection on daily changes, along with a quality of seeing everything around him afresh, put him in the tradition of the Continental “man of letters.” He was an aesthete, a moralist, and a bit of a dandy. His natty clothes were like his literary style, crisp and elegant but not flamboyant.

His preferred mode was description. He was convinced that whereas Westerners struggle to probe the depths, “The Japanese realize that the only reality is surface reality.” During a visit to Madison, he was delighted to find a translation of the Goncourt brothers’ journals. I couldn’t help thinking that he took them as a model of the urbane curiosity and pellucid prose he cultivated.

Above all he was interested in people. He was an excellent observer but also a well-tempered listener. He chatted with barbers, students, masseuses, neighbor ladies, potters, delivery boys, executives, and celebrities. He listened to their complaints, their dreams, and their reports on the texture of their lives. Sometimes they quarreled with him or disappointed him. But each one gave him a glimpse of the wavering mirage that was Japan, or at least his Japan.

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952).

His writing skills worked on a big canvas in The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959). He wrote the text while his collaborator Joseph Anderson, who read Japanese, provided the research. The book came at just the right moment, when Americans were starting to appreciate the power of this nation’s cinema. To this day, despite many specialized studies of directors, periods, and genres, it remains the standard overview of one of the great national film traditions.

Just as important, for me at least, was The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968). The first edition, a magnificent buff volume with razor-sharp illustrations and double-column text, is a triumph of book design, as solid and imposing as the films it canvasses. Along with Robin Wood’s works on Hitchcock and Hawks, it showed that cinema could be studied with intellectual seriousness. To the auteurist’s search for the guiding themes of a director’s vision, the Kurosawa book brought a sharp eye for technique and a direct access to the artist himself. (Our author’s first visit to a movie set was to Drunken Angel.) And it proved that a great film could sustain shot-by-shot scrutiny.

Turn to any chapter and you will see a probing intelligence. For Ikiru, we get a detailed layout of image/ sound relations in the nighttown sequence, bracketed by Watanabe’s funeral. The analysis carries us to this conclusion:

He has become much more than simply dead. Just as, dying, he learns to live; so, dead, he becomes more alive for others than he ever was before.

The Kurosawa book remains an exceptional achievement in sympathetic imagination. The critic is so finely in tune with the creator’s sensibility that each chapter illuminates and amplifies the dynamics of the film. There are other ways of understanding Kurosawa, but this book will remain the compass that orients us to this essential director’s career.

Floating Weeds (Ozu, 1959).

There were other books, of course. Among the best is the rare 1961 Japanese Movies, published by the Japan Travel Bureau. It is a compact survey of the major directors working in the postwar era. You sense that its intense aesthetic appreciation of particular films arises from portions cut from The Japanese Film. Here the critic is working at full stretch, and his thoughts on Naruse, Mizoguchi, and others are still worth reading. In its fifteen pages on Ozu, then unknown in the West, lie the seeds of his book on the director.

We have him to thank for our awareness of Ozu. He persuaded the reluctant Shochiku company to release the films in Europe and the US. His ten years of effort were crowned by the release of several Ozu films in New York in 1971-1972. At that point, largely as a result of accidental access, Tokyo Story emerged as the director’s official masterpiece. Soon afterward there appeared Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), another monograph informed by personal acquaintance with the director.

The Kurosawa book dealt in depth with each film, but this took a more horizontal and modular approach, tracing a skein of similarities across Ozu’s work. As one would expect, the emphasis falls on the postwar films, which were more easily available and which the author saw as they were released. (“Revisionist” takes on Ozu, and Japanese cinema as a whole, would soon return to the 1920s and 1930s and find there an earlier Golden Age.) The chapter layout tends to assume that Ozu films are more uniform than they are, but for its attention to themes and script construction in particular Ozu is indispensable. The author’s love for the films shines through every page.

It’s sometimes said that he brought Japanese cinema to the west, but apart from his championing of Ozu, this is inexact. Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, and Gate of Hell won an Academy Award in 1955. Daiei and Toho studios exported several films to Europe and America, while distributor Thomas Brandon sought to bring less-known Kurosawas to the US. The Japanese Film arrived at a propitious moment in 1959, when it could capitalize on the wider circulation of titles. Not until the 1970s was America to see a resurgence of interest in Japanese cinema, thanks to the Ozu releases, the Ozu book,the circulating programs sponsored by the Japan Film Library Council, and the efforts of Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films.

Still, our author did something quite important. By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture. Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic.

Although his major books remained essential for film lovers and film courses, it’s fair to say that he got a second wind in recent decades. He won a wide and keen following with his commentaries and liner essays for Criterion DVD releases of Japanese classics. The outpouring of grief after his death comes in large part from viewers who knew him best as a warm, calm voice talking through scenes of Tokyo Story or When a Woman Ascends the Stair or, surprisingly, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar. He adjusted well to the new world of video. He treated it as a new conduit for his commitment to civilized discussion.

Five Filosophical Fables (Richie, 1967).

So much for the public man, writer and speaker and animator of film culture. Another side of him was an intense erotic interest. On your first meeting, he made sure you knew what he found appealing. In the Journals, cruising and pickups blend with a swarm of local details of landscape and custom, although consummations are elided.

I had noticed that his suteteko, being thick cotton, are still damp from the swim, and so I suggest he take them off and hang them on a branch to dry. He does so.

*

Later, in the afternoon, I take a train around the coast. . . .

The juxtapositions between moments of artistic ecstasy and sexual passions give the journals a collage-like snap.

[Hiteki] got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. . . . Does everything but only, I feel because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. . . It represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 October 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves.

The diaries we have are very polished products, the results of much rewriting, and stretches are calculated to render the guilt-free sexiness that the wanderer finds all around him. Consider the finesse of this passage about a visit to Aoshima island:

Later we shop in the empty tourist arcades and buy some beautiful and indecent objects—cups you turn over to discover a coupled couple, an articulated vagina disguised as a shell, and a sake cup with a mushroom-shaped penis attached. One is to suck the sake from the mushroom head.

Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.

The surfaces might be rough. The journals record his enjoyment of living near Ueno Park, where the homeless and the prostitutes gather at night. He strolls through them, meeting the occasional cop and seeking, as he puts it, someone who can typify Japan in all its contradictions.

Beautiful and indecent: You can find this mixture in some of the experimental films he made too. The most inoffensive of these, Wargames (1962), was circulated among American film societies during the 1960s, but others are more audacious. In the allegorical satire Five Filosophical Fables (1967) a young man abandons a snooty party, strips to the buff, and strolls smiling through Tokyo streets, past the sea, and into the countryside. Cybele (1968), a documentary of an avant-garde theatre performance, presents an orgiastic rite of sex, degradation, and bloody sacrifice.

Roppongi Hills, Christmas 2010.

He was assailed by bouts of illness across two decades, but he seems never to have lost his buoyancy and spiky wit. He was especially mordant on the New Japan. He notes that the thrusting high-rise apartments of the 1980s bubble offer more for Godzilla to whack. “Originally [he] had to content himself with a mere Diet building.” Manga and the Sony Walkman were very much alike, he maintained. Each offered not visual or aural stimulation but a convenient way to shut oneself off from the ugliness of a money-grubbing society: solitary withdrawal amounted to a critique of contemporary life. With mock pathos he told of a salaryman so preoccupied with talking on his cellphone that a passing subway train snagged him and carried him off, the handset dropped squawking to the platform.

The humor could be self-deprecating. One of our conversations:

DB: I liked The Inland Sea.

DR: I traveled for three months and wrote it in three weeks.

DB: And I read it in three hours.

DR: You took too long.

When asked if he loved Japan, he replied, “That’s complicated . . . I love Tokyo.” Yet by the end of his life, his city had become alien to him. His Japan Journals begin by sketching the vibrant colors of a blasted landscape returning to life.

Winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The final entry in the journals is dated nearly sixty years later and records a 2004 trip to his old neighborhood. Tansumachi of 1947 had become the fashionable Roppongi Hills district, “the new Japan—gargantuan, expensive, and wasteful.” A Louise Bourgeois statue looms over the pavement like a tarantula. He recalls the street once named Dragon’s Way and the friend’s house that used to stand at that corner. He knows that his nostalgia must seem tiresome and he acknowledges that rapid change is itself a Japanese tradition, a sort of high-tech version of the Floating World. Yet he cannot resist denouncing the Disneyland that the old place has become. He finds no arresting color or light in this world.

In just a number of years every place will look like it, and this kind of economic expediency will be the rule, as will those cute nods in the direction of retro and trad, that comedy team of contemporary design. Here, under the spider, I look into the future which is already here.

He was well aware of living in-between. Today we might say that he was perpetually “other,” too aesthetically sensitive for a mercantile society, too protective of tradition in a period of lightning change, too gay for straitlaced America, too eccentric and independent-minded for assimilation into his adopted nation. Painful as these tensions must have been, he proudly accepted being fundamentally out of place. At the end of one essay he claims his motto to be that of Hugo of Saint Victor:

The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.

Extracts from Richie’s writings come from The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968 and later editions), A Lateral View (1992), and The Japan Journals, ed. Leza Lowitz (2005). Richie’s films are available on DVD as A Donald Richie Film Anthology from Image Forum Video. See also The Donald Richie Reader (2001), ed. Arturo Silva, for a varied collection of pieces, including articles on how he came to write about film, and his lively tour Tokyo: A View of the City (1999), with photos by Joel Sackett. The photo of Tokyo/ Hibiya crossing comes from the Journals, the shot of Roppongi Hills from Tokyofashion.com.

For a provocative review of The Japan Journals, see Richard Lloyd Parry’s “Smilingly Excluded.” Kim Hendrickson, who produced Richie’s DVD commentaries, provides a tribute on the Criterion site. A list of his commentaries and liner notes is on this page.

For more on how Japanese films came into the United States, see Chapter 6 of Tino Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973.

Thanks to Tony Rayns for conversations and assistance.

Elsewhere on this site are other Richie-related entries, particularly here and here.

P.S. 25 February: Karen Severns has set up a Donald Richie tribute page here.

Donald Richie at the grave of Ozu. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

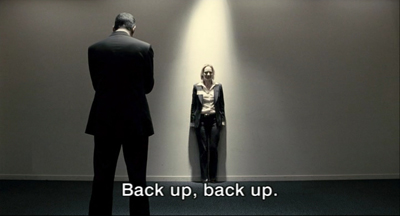

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).

Stretching the shot

Walker (2012).

It’s the editor’s job to think about coverage, and mistakes at this stage can have a very high price. Without that shot of the murderous feet walking slowly down the stairs, it’s impossible to build suspense. Inexperienced directors are often drawn to shooting important dramatic scenes in a single take—a “macho” style that leaves no way of changing pacing or helping unsteady performances.

Christine Vachon

DB here:

Go to any ambitious film festival, such as the Vancouver one Kristin and I are attending at the moment, and you’ll see several films made up of unusually sustained shots. Some Asian and European films may even be made entirely of long takes; in a few instances, none of the scenes may employ any editing at all. Movies made wholly of one-take scenes, or sequence-shots (plans-séquences) are probably more common today than they have been since 1920.

Why so many long takes? In the 1990s, when Vachon was writing, imitation and competition probably did come into play. The Movie Brats were sometimes up-front about their boy-on-boy rivalry. Here’s De Palma after seeing the shots following Jake into the ring in Raging Bull:

I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, “Whoa!” And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.

Something similar may have been going on in earlier times. It seems to me that in 1940s Hollywood, directors came to a new consciousness of the long take. Preminger, Ophuls, Sturges, and Welles became famous for their sustained shots, and even Hitchcock, a long-time proponent of editing, switched sides, making some of the longest-take films of the era. Sometimes an action scene might be played out in one flamboyant take, as in The Killers and Gun Crazy. It does seem that these big boys appearing to compete to see how long they could hold their shots and how complicated they could make them. One scene in Welles’ Macbeth runs a full camera reel, or about ten minutes; Hitchcock’s Rope contains only eleven shots.

Yet I don’t think that macho showoffishness or competition can completely explain the urge to shoot long takes. Watching the Vancouver Dragons and Tigers series leads me to consider some other options.

Long view of the long take

Naniwa Elegy (1936).

Of course there were single-take movies at the beginning of cinema, as in Lumière’s documentary shorts. And in the period 1908-1920, as I’ve argued in many entries on this site, some great films were made relying on single-shot scenes. They operated with a staging-driven aesthetic that’s come to be known as the “tableau” style.

But with the rise of American cinema to international prominence, and worldwide directors’ willingness to create scenes in the process of editing, the long take became relatively uncommon. In the 1920s, a rapidly-cut film might make occasional use of a long take, often as a fairly intricate traveling shot, as in Murnau’s Sunrise and Vidor’s The Crowd. Early talkies sometimes began with a long tracking shot (e.g., Sunny Side Up, Scarface) before settling into a more editing-driven style. And a few directors in Western cinema, like Max Ophuls, Jean Renoir, and John Stahl, handled extended dialogue passages in a single shot. A long-take approach was somewhat more common in Japanese cinema, with of course Mizoguchi Kenji being a prime exponent in films like Naniwa Elegy, Sisters of Gion, and Genroku Chushingura.

Citizen Kane probably helped popularize the long take in the 1940s, but so did the development of new camera supports. Dollies that could move through a set in tight turns encouraged directors to try out more sustained shots. For such reasons, most long takes of the period involved camera movement. Although Welles had his share of flashy tracking shots, he was one of the few directors who also let the camera stay fixed in place throughout a scene, in both Citizen Kane (Toland emphasized its “single, non-dollying” shots) and the extraordinary kitchen scene of The Magnificent Ambersons.

Occasional long-take shots have been with us ever since, some of them highlighting balletic camera-actor staging, as in Antonioni’s bridge encounter in Story of a Love Affair and many interior shots of Le amiche. By the 1960s, and 1970s, some directors became identified with long takes and even single-shot sequences: Tarkovsky most famously, but also Straub and Huillet, Miklós Jancsó, and Theo Angelopoulos. Fassbinder tried it out occasionally (Katzelmacher) as did Wenders (Kings of the Road). And of course in the avant-garde, devastating half-hour shots marked some works by Andy Warhol, not your most macho filmmaker.

There are still long-take films being made in the mainstream—not only those motivated as scavenged recordings like Cloverfield or Paranormal Activity, but also ambitious experiments like Children of Men. On the whole, however, long-take technique has become a hallmark of festival cinema. As commercial directors (not just in Hollywood) has embraced ever-faster cutting, other filmmakers have pushed toward ever-longer takes. It’s as if the rise of what I’ve called intensified continuity has provoked filmmakers to go to the other extreme. This impulse is thrown into still sharper relief by the fact that many of these festival films use little camera movement. And today’s shooting on video lets you hold shots a lot longer than shooting on camera reels.

But what does long-take cinema buy you?

Dragons, tigers, and stillness

A Mere Life (2012).

This year’s Dragons and Tigers series, the festival’s panorama of recent Asian cinema, had its usual quota of young people’s films about young people, not unlike America’s Mumblecore. The kids hang out, smoke, drink, flirt, berate each other, sometimes humiliate one another, occasionally come to a crisis in their lives. Other films were a bit more unusual. Several of all types, though, pointed up the virtues and limitations of current approaches to long-take shooting.

Most low-budget directors employing long takes don’t do so out of bravado or competitiveness. The reasons are more mundane: the tactic saves time and money. If you have rehearsed your actors, or if you want spontaneity and improvisation, you can get through a lot of your film more efficiently if you simply record the action. Editing in post-production comes down to choosing your best takes and finding the best arrangement of them.

For instance, Ninomiya Ryutaro’s The Charm of Others has about fifty shots in its eight-five minutes. Most scenes consist of only one or two shots. One seven-minute shot shows a young layabout Sakata trying to jolly his girlfriend out of dumping him. She’s seen him with another girl and tells him, “Eat first, then we’re through.” Instead, he pokes and tickles her, makes faces and jokes about liking to eat hair, and eventually wins her back. It’s a nice little examination of how men turn boyish, even babyish, when they’re trying to avoid a woman’s wrath.

Ninomiya, who plays Sakata, explains that although he had each scene’s core action fully scripted, he let actors improvise a fair amount during shooting. (Some specific words, however, had to be used.) The girlfriend scene was shot four times, the first three developing one approach to the action and the fourth take trying a totally different approach. Ninomiya wound up using the third take.

The Charm of Others is shot in a loose handheld style, with panning and tracking to follow its characters. This “free camera” technique is probably the most common way off-Hollywood directors employ the long take. The approach was on display as well in Mine Goichi’s The Kumamoto Dormitory. The plot follows a pair of slackers who want to work in films but lack ambition and anything approaching realistic expectations. More editing-driven, and somewhat more slickly made than The Charm of Others, it still averaged about eleven seconds per shot, a far cry from contemporary Hollywood’s average of five seconds or less.

For the most part, The Kumamoto Dormitory uses long takes in traditional ways–to record a scene’s interactions, and sometimes to create parallel story situations. In the beginning a lengthy shot drifts along dorm corridors as kids are moving in. One later in the semester shows boys in each room masturbating, playing mahjongg or computer games, and otherwise goofing off. Near the end another traveling shot shows the boys packing to leave as we hear an admistrator’s public speech describing how dorm life brings beginning students and graduating ones closer together. His inspiring line, “You were brought into the world because you were needed,” becomes ironic in the light of the dead-end hopes of a would-be movie director and his pal, an aspiring stunt man.

More rarely, the camera can be locked off during the long take, creating a static setup that may be refreshed by slight pans and reframings. Two of the films I’ve discussed earlier, Romance Joe and In Another Country, exemplify this approach; the former has fewer than 200 shots, the latter fewer than seventy. A similar approach, with a little more emphasis on dramatic compositions, is taken in Park Sanghun’s A Mere Life, a movie not about twentysomething crises but about the failure of a man to provide security for his wife and child. In a somewhat Mizoguchian tale of misery, most scenes are covered in only one or two fixed shots. There’s a striking scene in a café which obliges us to scan the background when a con artist bilks the husband and flees with his money. At another point, the camera’s refusal to budge and the director’s refusal to cut create considerable tension. Soon after the husband has lost the family’s savings, walls block our view of his desperate attempt to kill his wife and child.

The static long take is used in a more transparent way in Luo Li’s Emperor Visits the Hell, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers competition. The curious premise is that characters in present-day China are reenacting an episode in the classic saga Journey to the West. The reenactment, moreover, isn’t an affair of costumes or combat. It’s more abstract. For instance, the Dragon King is decapitated in the original story, but the Triadish character playing him in this film strolls around with his head firmly in place.

There are few single-take scenes, but the starkness of the décor and the fact that characters tend to be planted in a single spot give the film a sense of ceremonial gravity enhanced by the precise choices of camera position. Only in an epilogue, during the production’s wrap party in a restaurant, do the cast and crew assume their everyday identities. Then the camera goes handheld and roams bumpily around the table.

By the end Emperor Visits the Hell becomes a collection of contemporary long-take options: fixed versus moving, rock-solid framing versus shakycam.

Time on our hands

The long take has, we’re often told, another purpose: to capture real duration. Editing, it’s said, fragments not only space but also time. Whenever you cut, you have the opportunity to skip over dead moments. With a long take, especially a static one, the filmmaker is in effect asking us to register all the dead time between more important gestures, expressions, or lines of dialogue. This happens again and again in The Charm of Others, The Kumamoto Dormitory, and most of the movies I’ve already mentioned.

But the assumption of that “real time” flows through the shot can be questioned. The most common counterexample is slow- or fast-motion, which doesn’t respect the actual duration of the action the camera records. A rarer instance is offered by Tsai Ming-liang’s episode Walker in the portmanteau project Beautiful 2012, sponsored by the Hong Kong International Film Festival Society.

The action is bare-bones: A Buddhist monk walks through Hong Kong bearing a crinkly plastic bag in one hand and a sweet bun in the other. Across twenty-four minutes, twenty-one shots trace his progress through the city. In most the camera never movies, capturing the monk’s movement in static, sometimes abstract compositions. The catch is that the monk, played by Tsai regular Lee Kang-sheng, is advancing with preternatural slowness.

Sometimes we have to play a sort of Where’s-Waldo game with the compositions, searching for his stooped head or brilliant red robe or bare feet in a crowded shot. Most often, the emphasis falls simply on the monk’s movement. Hands lifted, head bent, he makes his way as if walking underwater. We watch each foot lift, shift weight, and descend in excruciatingly small changes of position. The movement proceeds not from camera trickery or CGI gimmicks; Lee’s performance presents a “temporal close-up” of humble, unstoppable walking. Meanwhile traffic, passersby, and other parts of his surroundings bustle along as usual. This is really stretching the shot–making the long take seem even longer.

One effect of these shots is to unroll an image of pure spiritual discipline, a sort of Zen exercise showing how microscopically an adept can control his body. Pedestrian yoga, you might say. Another effect Tsai creates is to summon up two times in one shot: that of normal activity and that of a spiritual tempo nestled within, but also opposed to, ordinary life. Eventually, when the monk bites into the bun, even that is rendered with the clarity of stop-motion photography. Here the long take exercises an almost scientific force, letting us see a simple act pulverized, as if a Muybridge image were translated into live action.

At the opposite extreme is the action-packed long take, running about seventy-five minutes, that comprises J. P. Sniadecki and Libbie D. Cohn’s People’s Park. The filmmakers had the good idea of taking us through a day’s pleasure in the city park of Chengdu, China, by means of a single traveling shot. A modern version of People on Sunday, the film unrolls a pageant of the everyday. People snack, trot past, make cellphone calls, rest on benches, sketch calligraphy on the paving stones, and above all make music. We see band concerts, karaoke performances, traditional opera, and spontaneous dancing to pop beats. The film starts with couples dancing and ends with an exuberant display of bouncy soloists who, we learned from Libbie Cohn after the screening, come often to perform for the sheer fun of it.

Just as important, instead of shooting at eye level, Sniadecki and Cohn filmed from a wheelchair. The lower-than-normal framing emphasizes kids, fills the frame with torsos, and yields unexpected revelations of figures in depth. We also get to watch a choreography of politeness as people subtly adjust to the camera as it squeezes through crowds or sidles among couples on a dance floor. Far from being the weightless, invisible camera of most Hollywood films, this camera and its carriage occupy actual space as the whole unit carves a sinuous path through the park. How, we sometimes wonder, will it get through here?

Many of the most famous long takes in film history are, we might say, teleological: They build toward a climax. Think of the tracking shot that opens Touch of Evil, beginning with a bomb set ticking and ending with an explosion. In a quieter way, the tableau aesthetic of the 1910s often gave the shot a distinct curve of interest, building to an expressive peak. (See here and here.)

And occasionally in today’s cinema, a shot that seems casual will subtly prepare us for a payoff. In The Charm of Others, a drinking game allows Sakata to tell others around the table what they must do. He orders two boys to kiss, and the girls join him in chanting, “Kiss! Kiss!” Those boys have already been present from the start of the shot, but now they become more than a pair of framing shoulders. Their obeying the order close to us furnishes an enjoyable topper for the take.

One problem facing the makers of People’s Park was the need to provide such a climax. As in Russian Ark, a single-shot feature film can’t simply stop; it needs to draw to a close, preferably on a striking note. In my view, Sniadecki and Cohn manage it. It would be unfair to tip you off–can there be such a thing as a stylistic spoiler?–but let’s just say it’s a moment of abrupt change within what is otherwise continuous, evenly-paced unfolding. Yes, dancing is involved.

In certain contexts, a long-take trend can, as Vachon mentions, exude a certain bragadoccio. Competition among artists, though, even with some bravado, isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as 1940s and 1980s Hollywood suggests. Sometimes as well the long take is an exigency demanded by time and money. It can yield artistic advantages, too, by building suspense (as in A Mere Life) or surprise (as in The Charm of Others) or both (as in People’s Park). It can also be a mark of virtuosity, a quality prized in most artistic traditions. A well-done long take can be like a sustained aria in an opera; its confident audacity can make you smile.

The epigraph quotation is from Christine Vachon’s Shooting to Kill (Morrow, 1998); the passage is available here. My quotation from Brian De Palma comes from “Emotion Pictures: Quentin Tarantino Talks to Brian De Palma,” in Brian De Palma Interviews, ed. Lawrence F. Knapp (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 148. I discuss stylistic competition in contemporary American film in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

I consider Mizoguchi’s use of the long take in Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light. Some elaboration of that chapter is on this site.

Toland’s explanation for avoiding cutting is explained in his essay “Realism for Citizen Kane,” available here. For more on his decision-making, see our book, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, as well as this blog entry. For more on 1940s “fluid camera” technique, go here.

The segments of the film Beautiful 2012 began life as online videos. They are linked at Hong Kong Cinemagic. They play rather jerkily on my laptop, but the motion in projection is completely smooth.

My thanks to Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, programmers of the Dragons and Tigers series, for their acumen and assistance.

People’s Park (2012).

Bon Cinéma! (miaou optional)

The Sorceror and the White Snake.

DB here:

For days, debates about the new Sight and Sound Poll have been saturating the Net ecosystem. The reach of the Web allowed editor Nick James to launch what may be a month-long striptease. (Well played, sir.) And likely you, reader, were weighing lists of masterworks.

But not me. I was watching Japanese space warriors blasting phosphorescent aliens to bits. I saw an amiable cannibal provide gory inspiration for a creatively blocked painter. I saw Dutch layabouts in mullets who made sponging off the system a death sport while calling each other “homo” and kut. I saw an ode to women’s armpit hair, moments of man-on-mule lust, and sexy female snake-demons writhing their way through two movies.

No candidates for the 2022 S & S poll here, but all in all, pretty diverting.

No hecklers, please

Montréal’s annual FanTasia is a three-week tribute to the world’s genre cinema. You get horror, SF, fantasy, martial arts, crime, and tasteless comedy. These movies are bloody, horrifying, outrageous, and hilarious. Nothing says entertainment quite like a wholesome family, complete with babe in arms, being plowed down by a delivery truck.

The name packs in a lot. I think it was first called FantAsia, as befit its early emphasis on Far Eastern imports, but the newer version shifts a little more emphasis to “fan,” which captures the tenor of the audience. Old folks worry that that the young avoid subtitled cinema. They should visit FanTasia, where teens and twentysomethings are happily watching movies from Iceland, Vietnam, Japan, Denmark, Hong Kong, South Korea, Thailand, and Holland. The brains behind this festival know what the kids want.

Don’t confuse this with Camp or Hecklevision. The multititudes come not to mock but admire. I suppose that’s partly because for decades smart genre pictures have woven moments of self-mockery into their texture, so as to mesh with that knowing, ironic attitude that characterizes our consumption of much popular culture. A closed loop: Genre connoisseurs make these movies, and other connoisseurs applaud them. Once you learn that Inglourious Basterds, Shaun of the Dead, Perfect Blue, Killer Joe, and Visitor Q have had premieres of one sort or another here, you get it: This is head-banging, but strictly quality head-banging.

The proof came with DJ XL5 Italian Zappin’ Party. This two-hour mélange of b-movie trailers and clips is a FanTasia tradition, having been preceded by Mexican and Bollywood editions. This year’s brew mixed snippets from fairly famous movies with glimpses of little-known items like Zorro contra Maciste, Spasmo, and The Three Fantastic Supermen. But the result isn’t exactly Camp, and it doesn’t attempt to mimic the media spew we see in Joe Dante’s Movie Orgy. Instead, typical trailers and scenes are tidily arranged in genres–peplum, spaghetti Westerns, giallo, and so on–and left to run at considerable length. Often the clips point up a recurring gesture or bit of iconography (decapitation, musclemen manhandling boulders). It’s less like zapping, more like an otaku assembling clips on a disc or in a file and inviting us over for an evening. Cheesy as many of these items are, we’re invited to appreciate the unpredictable energy of cinema that strives to shock.

The FanTasia tribe has its customs. At each screening, as the lights go down, you hear meowing, sometimes answered by barks or growls. One film started with bleating and clucking on the soundtrack, and this triggered a felicitous barnyard call-and-response; talk about surround sound. Nobody could explain to me the logic behind this FanTasia tradition–like streaking in the 70s, does it mean anything?–but its discreet silliness, perhaps distinctively Canadian, won me over. By the end I was joining in with a cracked miaou of my own. Yet once the movie starts, utter respect rules. Attentive silence is broken by appreciative laughter and whoops at those moments fans call OTT.

The festival’s ambitions are matched by the venues: raked Concordia University auditoriums with enormous screens and sound systems that envelop you. I sat in my favorite spot and didn’t regret it. Both film and digital projection looked sharp and bright. The staff get the audience in and out with dispatch, and everybody I met behaved with courtesy and good humor. Filmmaker Q & As are energetic and pointed. The movies are wild and sometimes abrasive, but the packaging is a model of civilized cine-festivity.

Never gonna grow up

You Are the Apple of My Eye.

The festival made its name with Asian popular cinema, and this year’s schedule didn’t disappoint. I could attend only the last week of screenings, so I missed some of the biggest titles, such as Peter Chan’s Wuxia, to be released in some markets as Dragon (innovative titling, eh? As we say in Canada.) But I did catch several entries.

You Are the Apple of My Eye, a Taiwanese rom-com, provides the now-standard mix of adolescent loutishness, romantic longing, and comic-book special effects. It starts with a twentysomething setting out for a wedding, and through flashbacks and voice-over, we learn of his high-school pranks and his surly affection for a charming girl in his class.

There’s always something touching about a gang of pals going their separate ways after school (viz., American Graffiti), so the film becomes more melancholy as the kids graduate and pass on to college and jobs; the only one who finds worldly success is a girl largely ignored by everyone. The plot shambles along, expecting us to be curious about whether the hero gets the girl he can’t quite learn to woo. The wedding culminates in a gag I found both clever and touching, a prolonged kiss–but not between the bride and our protagonist. And the motif of the ink-stained shirt, shown at beginning and end in a way that suggests a blue-bleeding heart, shows sophisticated sentiment.

School relationships are also character-defining in South Korean comedies, but their impact is more sub rosa in Love Fiction. Joo-wol is blocked after his first novel and is glumly working as a bartender. Attracted to a mysterious young woman, he pours all his literary talent into a Werther/ Cyrano effort to woo her. He even rhapsodizes about, and to, her armpit hair. Once they become a couple, however, he starts to write a murder thriller with her as a femme fatale. But his fiction leads him to investigate Hee-jin’s past, with disturbing results.

I thought this somewhat overlong movie tried to keep too many balls in the air–sequences dramatizing Joo-wol’s detective serial, flashbacks to his childhood, rumors about his girlfriend’s college sex life, and an excursion to Alaska. Again, though, it’s somewhat saved by a feel-good ending featuring Joo-wol’s friends in a scruffy band performing a karaoke video (above). As so often in the genre, stirring music redeems a meandering plot.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

You Are the Apple and Love Fiction center on young men who grow up painfully, bruising others in the process, but Vulgaria keeps us firmly planted in adolescence. Pang Ho-cheung, who has done interesting work in You Shoot, I Shoot (a hitman hires a filmmaker to document his killings) and other projects, gives us what is being packaged as Hong Kong’s dirtiest comedy ever. Reliable sources report that no film has ever before contained such filthy Cantonese. It’s not quite as raunchy as it’s billed, though, and it has a predictably soft center.

Chapman To plays a bottom-feeding movie producer who is drafted by a triad investor to make a sequel to the classic Confessions of a Concubine. The investor also insists on casting. He demands a part for the mule with which he seems to have an intensely physical relationship, and more centrally a role for Yum Yum Shaw, a decrepit beauty whom he remembers from the old days. Producer To agrees to all this while trying to keep the love of the daughter he shares with his divorced wife, and to continue a romance with a starlet with quality fellatio stylings. (Her secret weapon is Pop Rocks.) After an engaging setup, the plot gets thrown out of joint in typical Hong Kong fashion. To is knocked into a coma and recovers only to find the film finished and the patron displeased, not least because the director has redone the script with references to Al-Quaeda.

Not bad for a film shot in twelve days and made up as they went along. Still, I think that Pang made a capital mistake in not letting us see any of this bungled project. In particular, he set up the expectation that Yum Yum’s now sagging and plasticine face would be pasted on the starlet’s voluptuous body, and even cheap and clumsy CGI would have added to the fun. In any event, Vulgaria gets off some good-natured satire on the film industry in its financing crisis, and it provides many naughty laughs, not least in the sound effects that continue under the final credits.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Vulgarity was also the watchword in the Dutch comedy New Kids Turbo (2010). I was unaware of the TV comedy team New Kids, but their brand of politically incorrect slapstick is a little edgier than what we’d find in Hollywood. The aforementioned family-flattening gag and a passage in which policemen are amusingly shot probably wouldn’t make it past the producer notes in America.

Funny in small doses, this Five Stooges comedy of stupidity and aggression seemed to me to grow thin as it tried for more scale: the posse of dumb spongers refusing to pay for anything purportedly sets a model for the rest of Holland and calls forth repression from the authorities. I did learn that the planimetric framing on display in Napoleon Dynamite and Wes Anderson movies has become one default for harebrained humor in other countries. Or is it just an easier way to shoot groups of people?

Wuxia, fancy, plain, and very fancy

Painted Skin: The Resurrection.

Action cinema is a mainstay of FanTasia, and I caught several instances. Space Battleship Yamato is a live-action remake of the final installment in the anime series. As befits its origins, this version is rather classically directed, with prolonged medium shots and depth staging, as well as a soft texture that came through nicely on the 35mm print. It’s pure space-opera stuff, with a patriarchal captain passing authority to the young hothead and the emergence of romance between the hothead and the loyal young woman cadet. She turns out to be the secret source of energy that will turn the parched Earth into a green land again, but not without sacrifice in the long-established Japanese tradition.

To a large extent, the popular Chinese films of today are recycling tales and styles established by Hong Kong film in the 1980s and 1990s. Ching Siu-tung signed some of the best fantasy action films of those years (e.g., Duel to the Death, A Chinese Ghost Story, The East Is Red). Borrowing heavily from Tsui Hark’s 1993 Green Snake, The Sorceror and the White Snake offers your basic tale of the yearning and vengefulness of a woman-turned-demon. The main plot centers on White Snake, who falls in love with a herbalist and tries to pass for human. But Jet Li, looking like he’s suffered a few too many punches over the last three decades, is an abbot searching for demons to capture and imprison in his monastery. In a symmetrical subplot, the abbot’s young assistant turns into a bat demon but gains a friendship with White Snake’s counterpart Green Snake. When Li shows the herbalist his wife’s true nature, he breaks the marriage and unleashes White Snake’s fury.

Cue the video-game special effects for whirlwinds, floods, exploding temples, and soaring leaps. The airy effortlessness of all this comic-book spectacle made me yearn for the days of wirework; at least then gravitational heft limited the actors’ aerobatics. And cue a romantically inflated ending that pulls the couple apart to the tune of a duet sung by the pop-singer players on screen. A graceful, sinuous introduction of the two heroines (see the frame up top) and some interesting cutting in dialogue scenes (e.g., various scales of two-shots breaking up lines) couldn’t wipe away my sense that this has all been better done before–not least by Ching himself.

I did get my wire-work wish in Reign of Assassins, a pan-Asian project drawing on HK, PRC, Taiwanese, and Korean talent. Here Michelle Yeoh is given more to do than Jet Li was as the Sorceror. This film is engagingly old-fashioned, avoiding CGI for the most part and scaling the action to the everyday and the earth, not the sky. Michelle foreswears her past as an outlaw, undergoes the equivalent of plastic surgery, and tries to start fresh with a humble husband. But her old team’s search for the monk Bodhi’s corpse brings her back into action. In a plot twist reminiscent of the Shaw Bros. era, the husband reveals himself to be not all that she thought.

The fights are ingeniously staged by veteran Stephen Tung, but many are presented in that abrupt, disorienting framing and cutting that seems de rigueur these days. Taiwanese director Su Chao-pin is credited with story and direction, though a title on this print claimed the “co-director” to be John Woo, who was also a producer. On the whole, I respected Reign of Assassins more than I liked it. But nearly everybody thinks better of it than I do, as witness Justin Chang’s Variety review, the Hong Kong Movie Database reviews, and the customary detailed appraisal provided by Derek Elley in Film Business Asia. So maybe I should see it again.

The most elegant wuxia exercise I saw was Painted Skin: The Resurrection, fresh from its premiere at the Shanghai Film Festival (and in superb 35mm). King Hu made a version of the original tale in 1993, but this project has little relation to that, and only a tenuous one to the 2008 Hong Kong Painted Skin. That was a confused enterprise whose only redeeming feature seemed to me to be Donnie Yen. This installment more or less abandons the plot material of the 2008 film, while keeping many of the performers. It’s a solid, confident achievement, blending pathos, romance, and fantasy with an unhurried restraint largely missing from The Sorcerer and the White Snake.

Like that film, there’s a double plot centering on two female demons. A fox demon offers to swap her body for that of a disfigured princess, while in a minor-key subplot a bird demon develops affection for a demon hunter. Director Wuershan, fresh off his success with The Butcher, the Chef, and the Swordsman (2010), treats both the magic scenes and the erotic encounters with a grave warmth that elevates them above the genre standard. If you can have dignified eye candy, this movie offers it: sumptuous costumes and sets, striking but not go-for-broke special effects, combats that discreetly exploit the stammering ramping effects of 300. But the oscillating relations of the two central woman, tracing rivalry, complicity, envy, and loss, remain firmly at the action’s center.

Hong Kong filmmakers developed these mythic formulas in the 1980s and 1990s, when such “feudal” and “superstitious” subjects were forbidden on mainland screens. The slick assurance with which new mainland filmmakers have mastered this material suggests that in the new liberalization of the mainland market, they now own this genre. Painted Skin: The Resurrection has quickly become the biggest box-office hit in PRC history.

Crossovers

Carré blanc.

Everyone has noticed that genre pictures are getting artier, or art films are getting more genre-fied. Crossover efforts can yield strong results, as shown by movies as different as Let the Right One In and Drive. The title Eddie the Sleepwalking Cannibal would seem to signal B-movie giggles and gasps, but it turns out to be a tight, restrained study of the sadism driving artistic creativity….and a certain number of giggles and gasps.

A painter in a career slump, and following an unspecified “accident,” accepts a teaching post in a Canadian art school in hopes of calming down. He takes in a mentally deficient young man who grabs and eats animals while he’s sleepwalking, or sometimes sleeprunning.  When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

When you learn that the painter’s neighbor is an obnoxious oaf with a perpetually barking dog, you begin to think that Eddie will be the painter’s means of securing peace and quiet. Actually, Eddie’s depredations unlock the painter’s creativity, inspiring a new burst of excellent work. Thereafter, he’ll need to keep Eddie on the prowl.

The film balances gore, comedy, pathos, and satire of the art world. When the painter realizes that the young woman he’s slept with is a good sculptor, his efforts to deflate her using CritiqueSpeak reveal that his apparent humility covers an angry competitiveness. Eddie isn’t exactly Henry James on the creative process, I admit, but it’s not A Bucket of Blood either. The movie looks very trim and polished, with excellent sound work; I regret only the tendency to treat every dialogue scene in a fusillade of tight close-ups, which leads to a fairly unvarying pace. There’s a reason Coen brothers cut fairly slowly and stay far back; this sort of queasy deadpan tension benefits from steadiness and silence.

The screening of Carré blanc was preceded by La Jetée, as a tribute to Chris Marker. It was completely appropriate. For one thing, La Jetée hinges on one of the paradoxes of time travel: Can a man witness his own death? This sort of mind-bending was amusingly dealt with in Aleksey Fedorchenko’s “Chrono Eye,” one of three shorts in the portmanteau movie The Fourth Dimension. A scientist clamps a camera to his head and tries to tune himself to the future or the past, with the results transmitted to a beat-up TV receiver. The film makes clever use of the fallen-camera convention, and it ends with a rejection of past and future in the name of a vivacious present.

La Jetée was prophetic in another way. Before Marker’s film, most science fiction movies, from Metropolis and Things to Come to The Time Machine, used fanciful sets to conjure up the future. But Marker realized that one could film today’s cities in ways that suggested that the future was already here. This opened up a rich vein of exploration in Alphaville, THX 1138, Le Dernière combat, and their successors. And if you haven’t noticed: That future-tense present is always bleak, totalitarian, and something to escape from.

No wonder, then, that Carré blanc becomes an arty dystopian fable about a boy and girl brought up in a totally administered society. Philippe’s mother commits suicide so that he can be taken into an orphanage. There he will be turned into “a normal monster,” thus assuring his survival. Grown-up, he’s a high-level bureaucrat administering childish tests that his victims never seem to pass. But his marriage to Marie is withering. They can’t have a child, and she spends her days wandering the city. Eventually things come to a crisis and the couple must decide whether to stay or try to flee.

The plot is pretty formulaic and some of the absurd touches seem forced (the national sport is croquet). But the pictorial handling engages your interest from the start. Call it “1984 meets Red Desert,” except that there’s not much red here: bronze, black, and amber dominate. Simple techniques, like lighting that hollows out people’s faces to the point of blankness, become very evocative.

As in Alphaville, actual locations are made sinister by the dry public-address announcements saturating the soundtrack. The vast net stretched outside the couple’s apartment complex recalls the harrowing images of suicide-prevention nets at Chinese factory complexes. What a pleasure to see a movie designed shot by shot; the fixed camera yields one startling composition after another. Familiar as the story and themes are, the style grows organically from them. Carré blanc was the most impressive piece of atmospheric cinema I saw in my FanTasia visit.

So why was I here?

To see the movies. To catch up with old friends like Peter Rist and King Wei-chun and to make new ones. To present a talk on the Hong Kong action tradition. And to get an award for “Career Excellence.” Say hello to my lee’l (actually not so lee’l) frien’.

I’m very grateful to the coordinators of FanTasia for inviting me and honoring me with this magnificent award. It was an unforgettable week.

In addition to all this, FanTasia held an avant-premiere of the exhilarating ParaNorman (below). After I’ve seen it again, preferably with Kristin, I hope to write about it here.

Jason Seaver has blogged loyally about the festival on a daily basis. Liz Ferguson has a series of articles in the Montreal Gazette. A short interview with me appears on the FanTasia YouTube channel. Juan Llamas Rodriguez offers a two-part commentary on it starting here.

P. S. 11 August 2012: Daniel Kasman of MUBI has provided a link to Chris Marker’s little-known site Gorgomancy, which includes viewing copies of some of his little-known films.

P. P. S. 13 August 2012: Marc Lamothe–film director, co-director of FanTasia, and creator of DJ XL5’s Italian Dance Party–writes to explain the origin of the meowing.

Besides my national genre cinema tribute, every year since 2004 I’ve edited a short film program for FanTasia. It’s constructed the same way the Italian zappin’ was. I put static between films and include old vintage videos, ads and obscure film trailer in between films to simulate an evening of zappin’. This brings an energy and rhythm to short film presentations.

In 2008, I had a screening entitled DJ XL5’s DJ XL5’s Hellzapoppin Zappin’ Party. The program was constructed in 2 parts, with each part on a 60-min beta tape. Both part one and two contained episodes of Simon Tofield’s Simon’s Cat. To switch from beta one to beta two meant some 30 seconds of blackness and silence in the room. As Simon’s Cat made a strong and loving impression on the crowd, during the short intermission for chaning from tape 1 to 2 some people started meowing to break the silence. That made the others laugh and signaled their affection for the character.

This inside joke spilled over into more serious film presentations and has became a staple of our audience. Here’s the film responsible for the phenomena: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w0ffwDYo00Q.

Thanks to Marc for the information, and for a fine festival. Thanks also for his kind words about our work; he read the second edition of Film Art back in the early 1980s!