Archive for the 'National cinemas: Japan' Category

Splashy and spare, vengeance and regrets

DB here at the Hong Kong Film Festival:

Above, a tourist pic, the view from one of several escalators in the towering mall in Langham Place. Its flamboyance makes a sharp contrast with the movie I saw in the mall’s cinema, the minimalist Turin Horse. (See below.) The very end of this entry presents another view from the heights of Langham.

Righting wrongs, with new wrongs

Heaven’s Story.

Most Hong Kong thrillers and action pictures use revenge as their mainspring. It’s fairly uncommon, however, for a film to try to convey the cost that vengeance exacts on the avenger. Punished, directed by Law Wing-chong and produced by Johnnie To, makes an effort in this direction. A mogul’s spoiled daughter is kidnapped, and his refusal to bend to the captors’ will leads one, in a moment of pique, to kill her. After learning of her death, the mogul contracts with his chauffeur, a man who knows the underworld, to track down the gang.

The tycoon, played by Anthony Wong, goes through some agonizing as he must hide his daughter’s death from the girl’s stepmother. In turn, the chauffeur, Richie Jen (whose skilful performance dominates the movie), must abandon his son after executing the boss’s revenge. The men’s lives dissolve in their quest for payback, and the fact that the daughter, a brattish cocaine addict, is completely unsympathetic only makes the whole thing bleaker. An obvious parallel is the Eurothriller Taken, which presents a rash but innocent daughter rescued by a father who remorselessly cuts down everything in his path. Well-mounted, with perhaps too many flashbacks, Punished is that unusual Hong Kong film that insists that every effort to assuage male pride takes a toll in male pain as well.

But for a film that really investigates the cost of settling accounts you have to turn to Heaven’s Story. Here Zeze Takahisa, known mostly for erotic films, traces out the consequences of three killings. The cop Kaijima impulsively shoots a suspect. The locksmith Tomoki’s wife and child are brutally murdered by a teenager, Mitsuo. And elsewhere the little girl Sato is the only survivor of another family homicide.

The stories link up. Sato, in numb grief, sees Tomoki on television vowing to kill Mitsuo when he leaves prison. Because the man who killed her family has committed suicide, Sato embraces Tomoki’s reckless vendetta. She grows up hoping to help him kill Mitsuo. At the same time, Kaijima’s son develops a sidelong relation with her….

I really haven’t given away much, because the film traces these characters and several more across the space of—yes!—four and a half hours. As in a novel, the motives and connections among characters emerge slowly. Zeze’s plot maintains a balance between suspense about what comes next and curiosity about the past. And as in most network narratives, part of the pleasure is wondering how the new characters we meet will tie into the ramifying web of relationships.

Zeze splits the film into two “acts,” with intermission, at a bold spot: ending the first part on a pitch of suspense and starting the second with a new set of characters, making us wait for the developments set up at the end of act one. Working on a broad canvas allows the film to shift majestically, in large blocks, from one person to another. The same goes for the ending: After the main drama is resolved, Zeze allows a long epilogue in which many of the film’s motifs are gently set to rest.

That drama and those motifs, unsurprisingly, bear on the power of unspeakable acts to ignite our desire for revenge. Every character, even those unaware of the savage deaths in the past, is altered by the central killings. An amateur rock singer, a young woman almost defiantly self-centered, becomes a devoted mother, which seems to yield some hope; but her family is eventually shattered by echoes of Mitsuo’s crime.

Those more directly affected by the killings face more severe tests. Kaijima, for instance, tries to compensate for his impulsive shooting by giving monthly money to the victim’s wife and daughter. (The irony is that the money comes from his sideline, moonlighting as a paid killer.) The daughter grows up expecting Kaijima’s payments as her due and tries to extract more money from him, as if he were her surrogate father. This daughter, along with Mitsuo the teen murderer and the older woman who takes him in, come to unexpected prominence as the film unwinds a tale of sorry lives and compromised choices.

Mostly shot in rough-edged, somewhat bumpy shots, Heaven’s Story at first made me fret: 278 minutes of this? I needn’t have worried. The pace is steady, even relentless, but I didn’t find it monotonous, and a more polished presentation might have lacked the distressed urgency of what we get. Incidentally, the framing bits, showing a sinister puppet play with Shinto overtones, are filmed with smooth care. The contrasts in technique suggest that a more serene supernatural domain exists alongside the anxious sphere of human desires, where people persist in trying to redress old sins by committing new ones.

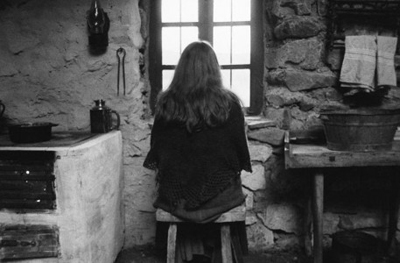

The obscurity of the everyday

A horse is feverishly hauling a cart, the camera riding low underneath the beast’s plunging head. The wheezing repetitive score rises to a scraping whine, then it’s replaced by the sound of fiercely whipping wind. The old driver pulls the cart up at a farmhouse, where he’s met wordlessly by a younger woman. As the wind tears at them, they take the horse to the barn, the cracked leather harness left on the cart. Inside the cottage, the woman helps the man change his clothes. The woman boils a pair of potatoes. She says: “It’s ready.” It’s the first line of dialogue, and it comes nineteen minutes into the film.

Thus begins the festival film that has exhilarated me most so far, The Turin Horse. With this movie, Béla Tarr, a favorite of mine (especially here, but also here and here), has given us his most spare entry yet. Almost nothing dramatic happens during its 140 minutes, and what does take place is opaque and enigmatic. The film refuses traditional exposition, forcing us to observe bits of behavior and speculate on why things unfold this way.

At one level, it’s the heritage of Neorealism paying off. In Umberto D’s scene of the housemaid preparing breakfast, we had an early example of sheer dailiness used to characterize a person and a milieu, as well as to absorb us in what we might call mundane beauty. But something different, more abstract and disturbing, happens when a film is nearly all routine. In the farmhouse, the old man and his daughter eat their steaming potatoes barehanded, squeezing and mushing them. He wraps himself in a blanket and stares out the window while she does household chores. Next day they arise, dress, and hurl themselves again into the blasting wind. (The wind ripping along the wet streets in Sátántangó is nothing compared to this gale.) In all, cramped settings observed with Tarr’s usual tactile detail, rendered gorgeous in black and white, become as obscurely allegorical as the magical tabletop in Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Other characters show up eventually. An hour in, a talkative friend arrives and provides a monologue cursing the ignoble forces that have driven intelligence from the world. Later some travelers appear outside at the well, with malevolent results. And the horse refuses to be fed. Perhaps at bottom the “story arc” is that light simply goes out of this world. Having dwelt on gestures (hands pouring out alcohol or struggling to harness the horse) and textures (the ripples of woodgrain on the stable door), the film slides into darkness. The motif is announced in the cryptic trailer for the movie.

From Tarr’s comments we learn that the man is a carter and the woman is his daughter. The film’s voice-over prologue invokes an episode from the life of Nietzsche, who once tried to stop a driver from mercilessly whipping his horse. The incident purportedly led to Nietzsche’s descent into insanity. Tarr has said that the film, based on a short story by László Krasznahorkai (who also wrote the novel Sátántangó), tries to imagine what happened to the horse after the incident.

Yet the horse is less important in the film than the carter and his daughter. It’s not hard to see them living a post-Nietzschean world, and the visitor’s rant about universal debasement may offer support for this interpretation. It’s another exercise in what an earlier entry called Tarr’s “postlude” vein, presenting what remains of life after history has more or less ended. Yet these are no stick figures in a metaphysical meditation. Virtually without psychology, father and daughter are defined through their sheer physical weight and movements. They confront the blasted landscape when they pass outside and the wind tears at them, but once inside they shift to the window to watch. The image of an observer trying to understand a harsh, senseless world beyond the walls is one we’ve seen in the opening of Perdition, and in the scene in which the obese doctor in Sátántangó planted at his desk tries to write down everything he sees happening outside.

Not that the cottage is any more welcoming. Splendidly filmed from a constrained variety of angles, the cottage seems bare of love, meaning, and what we normally consider drama. Tarr’s camera movements and the solemn rhythms of his shots (I counted only 37, including intertitles) are coordinated with the pace of the characters. Perhaps not since Dreyer’s Ordet has the lumbering pace of country life, the trudging gaits and reluctant effort to rise after sleeping, been rendered so expressively. Here, however, nothing is touched by grace

Tarr makes his inhospitable world spellbinding. I’m ready to watch the The Turin Horse again, even, or especially, if it proves to be Tarr’s last film.

For a detailed, less sympathetic review of Heaven’s Story, see Peter Debruge’s piece in Variety. Suggesting that The Turin Horse will be his final film, Béla Tarr discusses it here. At The MUBI Notebook, David Hudson has provided very informative coverage of the controversy around Tarr’s place in Hungarian cultural politics. For an interview with Tarr’s cinematographer, as well as a sensitive appreciation of the film, see Robert Koehler’s piece in the new Cinema Scope.

A view from Langham Place shopping mall, Mongkok.

Direction: Come in and sit down

Tampopo (1985).

There is what we call the Hollywood Style. . . . . Master shot [filmed] from the very beginning [of the scene] to the end, then a close shot from beginning to end, then from angles A and B, cutaways, et cetera. Then all of the materials are assembled later in the editing room. But in Japan, the editing plan is prepared before shooting. When you cut, it’s a matter of trimming heads and tails and just putting it together. Three days after the end of filming, there is a rough cut of the film.

Itami Juzo (The Funeral, A Taxing Woman).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong 2 still on the way…. very close to ready…. deciding among cover designs…. soon; sooner if possible….

In the meantime, some creative choices involved in directing a simple scene.

Shanghai’d

What could be easier than getting a man into a room and sitting him down? The opening scene of Shanghai (2010) seems to me to bungle this basic piece of tradecraft.

In the image above, journalist and spy Paul Soames is being beaten up by the minions of Captain Tanaka. Who’s the poor sod who has to hang those big flags so high in movie torture chambers like this? Anyhow, soon the torturers drag Soames up the stairs, likewise in long shot, to meet the captain.

A brief shot of a door opening seems to put us in Soames’ shoes. But that viewpoint isn’t carried through consistently: we cut abruptly to the other side of the door, to a long-lens medium shot of Tanaka opening it.

Soames steps forward and is greeted by Tanaka.

Now comes the establishing shot, from quite far away, as Soames walks to the desk. This shot is interrupted by cutting back to the shot of Soames moving forward.

As the shot continues, Soames sits down and looks up. Throughout the scene, this setup will be assigned to cover Soames, with the camera panning and reframing as necessary.

Counting the swinging-door shot, it has taken four shots to get Soames into the room. But the actors aren’t yet fully in place. As Soames turns his head, Tanaka (back to master shot) moves around on Soames’ left side. The phone starts ringing.

Tanaka begins to halt at his desk, but before he stops moving we cut again to Soames, whose attention has shifted to the phone. He has asked that his embassy be notified, and now he suggests that it’s the embassy calling.

Cut to a close-up of the telephone, the object of Soames’ attention, and another shot of Soames, as before, as he looks expectantly back at Tanaka.

Now we have a closer shot of Tanaka, still slightly moving, and we catch his disdainful expression.

After Tanaka lifts and drops the receiver to cut off the call (another close-up), he settles into place. The rest of the conversation is played out in those loose over-the-shoulder shots that modern directors like so much.

Throughout, the shots of Soames seem to be from the same camera setup as when he entered. No repositioning of the camera marks stages of his part in the conversation, though at the end of the scene a pair of close-ups shows Tanaka asking, “Where is she, Mr. Soames?” Cue the flashback.

It’s not just that it took director Mikael Håfström over a dozen shots to get Soames and Tanaka into position for their central duet. Hitchcock might use several shots too. But each of his would be calibrated for specific expressive effects, such as subjective point-of-view treatment or a striking composition. Instead, the Shanghai shots exemplify a fairly casual cover-everything approach–a scattergun version of what Itami called the Hollywood Style.

Here the individual shots make a big deal out of a simple piece of business. We don’t need to see all of Tanaka’s office (since the rest of the space never gets used in the scene), and it doesn’t need to be so vast in the first place (except to announce that this is an expensive movie). The long-lens camera setup that lets Soames advance into the room and sit exists solely to let us watch the actor act, and it provides awkward cuts when bits of it are embedded in extreme long-shots.

It’s not hard to imagine alternatives. A straightforward tracking back from Soames as he enters and sits, framed from further away, would have kept both him and Tanaka in the frame. This framing could have easily shown Tanaka coming around to take up a position in the foreground by the desk, perhaps turned partly toward us so that we could peg him as a major character. Then if you insist on a cutaway to the ringing telephone, it would have had more impact, interrupting a sustained shot and contrasting to the fuller frame showing the two men.

Today many directors believe that we must always see the face of the person who’s speaking. So we get lots of shots, mostly singles, one per line, and each face is usually in close-up or medium-shot. Hence the great number of cuts per scene; here, counting from the swinging door, we get 23 shots in 97 seconds. And hence the repetitive reverse shots that cover the conversation.

I’m not the only one who notices these things. “If I see another over-the-shoulder shot,” says Steven Soderbergh, “I’m going to blow my brains out.”

Television probably has a lot to do with the emergence of this style, as some historians, me included, have argued. You have to be a good director to overcome the choppiness inherent in this manner of filming. I don’t think that Hafstrom did that. If the director had planned his shots in the finer-grained way Itami indicates, we might have had more visual variety, along with compositions and cutting that take us beyond the actors’ faces and line readings.

Dandelion soup

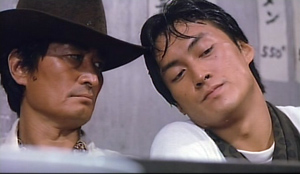

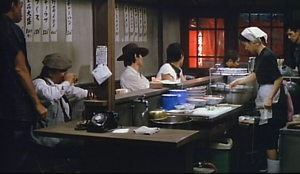

Now we might look at how Itami does it. An early scene of Tampopo (1985) also demands that a man, along with his sidekick, come into a room and sit down. We see Goro the trucker and his pal Gun enter the noodle shop, along with the little boy they’ve found lying on the street. We see them first from outside and then from inside the new locale, much as in our Shanghai example. But there’s no need for anything like that insert of the opening door.

Cut to a point-of-view shot that makes a point: Goro is entering a room full of thugs. Itami pans to show two knots of men in the shop, some of them threatening.

While each Shanghai shot does one thing at a time, this shot does two things at once. This shot sets up the hostilities that will ensue, while also laying out the space of the shop and positioning all Gun’s adversaries in it, along with the proprietress Tampopo.

Cut back to the men at the door, but it’s a different framing, from further back, than we saw initially. Now some of the thugs are staring at our heroes.

Itami is calibrating his compositions to give us new information. If this composition had been used for the first shot of the men entering, the subjective pan across the room wouldn’t have been so surprising. Now the camera cranes back to follow Goro and Gun striding to the middle of the shop and sitting down. They order bowls of noodles.

This orientation will be the dominant one in the course of the scene. But the space isn’t as bare as in the Shanghai scene; the men we see dotted around the room will play important roles in the action now and later. As in the Shanghai scene, there are cuts to close-ups, but they show more informative items than a ringing telephone. One shot picks out Tampopo herself (establishing her as a major character), another picks out Gun’s skeptical view of her cooking technique, and a third tilts down to show her hands cooking noodles in water not yet boiling.

To the noodle connoisseur Gun, this proves that she’s a maladroit cook, and another shot of the two men shows his reaction.

Cut to a long-shot. The long-shots of the office in Shanghai are always from a single position (the result of straight-through master-shot coverage), but here we get a slightly different framing than we’d seen earlier. The camera is somewhat lower, which allows Itami to stage a little piece of business. Tampopo’s son Tabo runs unseen out from behind the young thugs, along the aisle behind the stools, into the foreground, and out frame right. He has been beaten up outside, but Tampopo takes it in stride.

When Tabo has gone, the men resettle in for the next phase of the scene, when Tampopo serves Goro and Gun. The entire shot we’ve just seen is held for forty-one seconds. Soon a fight will erupt, delaying the revelation of how awful Tampopo’s noodles are.

This is not virtuoso direction, but it is smooth and precise. Each shot blends with the next with a degree of care we don’t get in the Shanghai instance. That’s partly because each shot is given its own small, completed arc of action. (The nine shots I’ve listed run ninety seconds.) For example, Tabo’s run down the aisle is prepared by a slight shift in Goro’s glance at the end of an earlier shot I’ve mentioned. He looks toward the door and tells Tabo he’ll catch cold.

This moment prepares us for the next bit of action, while also setting up the trucker’s gruff concern for the boy, an important element of the plot to come.

More generally, across the whole scene each long shot does more than simply orient us or cover changes in position; it’s enlivened by movement and incident. Nothing in the Shanghai scene approximates Itami’s willingness to let body language replace facial close-ups. Here Goro coolly samples the noodles while the gang prepares to rumble.

Later, an entire scene will be played in a packed long shot lasting nearly a minute. Goro has brought Tampopo to watch a master chef at work, and Itami is perfectly okay with concealing her face as she calls off all the orders that people have just made. We don’t need a close-up of her expression when she speaks; the important thing is her aptitude and the customers’ enthusiastic applause.

An unassertive shot like this, you want to say, respects the audience by letting us see everything that matters at each moment. We call it directing a movie.

Itami’s remarks in our epigraph come from Bob Strauss, “Director Juzo Itami,” Premiere (June 1988), p. 25. Soderbergh’s comment about OTS shots is taken from “Matt Damon: Steven Soderbergh really does plan to retire from filmmaking,” at the Los Angeles Times.

Shanghai has probably not come to a theatre near you. Delayed during the shooting, it sat on the shelf for some time before its premiere last summer in China. It’s announced for U. S. release in 2011 but the Weinstein company website says only that it’s “coming soon.” Planet Hong Kong redux will beat it, for sure.

As chance would have it, Tanaka in Shanghai and Gun in Tampopo are both played by Watanabe Ken.

My arguments about the emergence of this “intensified” version of classical continuity are made in The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 117-189. I’ve done a blog on the idea here; it’s hardly fair for me to compare Nora Ephron with Lubitsch, but she sort of asked for it. For more on economical staging and cutting, see our entry on Spielberg’s shooting style, as well as the idea of the Cross. For another comparison of Hollywood direction with an Asian alternative, see our entry on Jackie Chan’s Police Story.

A. D. Jameson makes strong points about inefficient shot breakdown in his essay “Seventeen Ways of Criticizing Inception.” Jameson invokes The Ghost Writer as a good counterexample, and indeed Polanski’s film often displays the sort of cut-to-cut restraint and control that Itami calls for. Jameson elaborates further in another epic post. There’s also an intriguing discussion at Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog of how much a filmmaker should rely on close-ups; the film at hand is Black Swan.

P.S. 5 January 2010: We’ve had an enthusiastic response to this entry; thank you, Twitterers. It occurred to me that readers might be interested in a similar comparison between Asian filmmaking and U.S. practice in a very early entry, back in 2006. Ironically, Soderbergh’s Good German was involved, the subject of an earlier post. The contrast case was Johnnie To’s PTU.

Shanghai (2010).

Vancouver: Final freeze-frames

DB here:

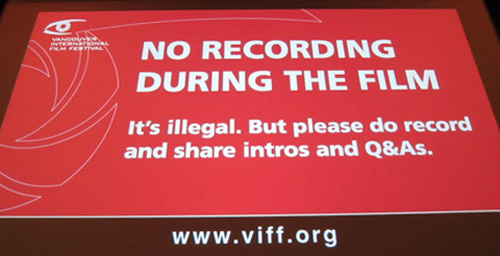

This slide, which appeared briefly before every screening at the Vancouver International Film Festival, epitomizes one of the event’s virtues: quiet sanity. Of course we must discourage people from recording the movie. But just as surely, we want people to photograph the filmmakers and record their comments and get the word out. Spreading the news benefits everybody, particularly the filmmakers.

Indeed, the whole VIFF clambake is run as efficiently as anyone can imagine. Want to get into a film? Very likely you will. A movie is getting buzz? Likely as not, extra screenings will be mounted. Annoyed by mobile devices in the throngs around you? House managers firmly ask people to shut them off. Now. Yet there’s nothing aggressive here. This is a city in which the buses preface the flashing notice “Out of Service” with an apologetic “Sorry.” A Manhattan bus would say, “You’re outta luck, pal.”

Now that Kristin and I are back, we know whom to thank: the organizers, the programmers, the office staff, and the inexhaustibly cheerful volunteers (700 strong). Below are Alan Franey, Festival Director, and PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager and Senior Programmer.

Come down for breakfast and you’re likely to run into Foreign Guest Coordinator Theresa Ho and Hospitality Suite Manager Eunhee Cha Brown. Dreyfus is usually not far away.

Then there’s the multi-talented Lillooet Fox, Food and Beverage Coordinator, waffle wrangler, and music supervisor for Amazon Falls, playing in the festival.

Ever notice how film people are always “on,” always subtly copping stances and looks from movies? Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers programmer, does his dressed-down version of Lars von Trier.

Speaking of T-shirts, nothing beats telling a story with your thorax. Consider Sean Axmaker (Parallax View) and Robert Koehler (Anaheim International Film Festival) and Raymond Phathanavirangoon (Hong Kong International Film Festival).

At happy hour, the waffles vanish and adult beverages come into their own. VIFF programmer and editor of Cinema Scope Mark Peranson hoists one with Variety critic (and University of Wisconsin alum) Rob Nelson.

Of course everyone mingles with filmmakers. Freddie Wong, director of The Drunkard, is reunited with Bérénice Reynaud, Cal Arts professor and author of a book on City of Sadness.

Tony Rayns, veteran Dragons and Tigers programmer, is flanked by Bong Joon-ho on the left, Denis Côté (Curling) across the table, and Mark Peranson on the right. Geoff Gardner and Jack Vermee are in the distance. Again, the cinephiles pay homage to a shot, in this case from Hong Sangsoo’s Oki’s Movie.

Jim Udden, another Badger and Professor at Gettysburg College (and author of a book on Hou Hsiao-hsien), talks Taiwanese film with director David Verbeek (R U There?).

Trustworthy translator Alex Fu and director Zhu Wen (Thomas Mao).

Takahashi Nazuki and Abe Saori celebrate after their screening of Icarus Under the Sun.

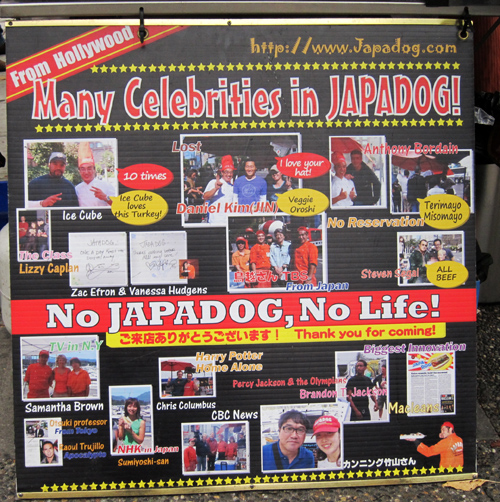

Meanwhile, Geoff Gardner (watch for his VIFF coverage in Urban Cinefile) finds that a rival venue has conjured up a star from another era.

And although we left Vancouver all too soon, we’ll always have Japadog. Not everything in Vancouver is quiet sanity, but even the nuttiness is quite easygoing.

I recommend no. 4, Spicy Cheese Terimayo.

The Dragons & Tigers’ late-night roar

Thomas Mao.

DB here:

First, the news flash: Tonight was the awards ceremony for the Dragons & Tigers competition for young filmmakers here at Vancouver. A jury doesn’t get more distinguished: it consisted of (left to right) Jia Zhang-ke, Denis Côté, and Bong Joon-ho.

They awarded two special mentions, one to Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (from Vietnam) and to Xu Ruotang’s Rumination (China). On the last-named, check the still at the end of this entry.

The grand prize went to the Japanese film Good Morning to the World!, by Hirohara Satoru.

More details here. Congratulations to the winners!

Beginners’ luck

My Film and My Story.

Vancouver is unusually hospitable to shorts and features by newcomers. Two of this year’s D & T offerings illustrate how talent, unlike youth, is not wasted on the young.

A cinémathèque featuring classic films is about to reopen, and the manager has hired some twentysomethings to help her get things into shape. The result a network narrative: romantic rivalries, coming-of-sexual-age crises, the race to set up the screening space, and even a ghost story are woven together as the big day approaches. The film is split into eight chapters, each given an emblematic movie title. Two petty thieves interview for a job under the aegis of “Stranger than Paradise,” and an apparent love triangle is christened “Jules and Jim.” The cinephilia shapes the plots too, as when one boy gets the courage to kiss another after watching Happy Together.

My Film and My Story was a group project of students at the Art and Design School of Konkuk University in Seoul. Their professor proposed that each student write a script about the opening of the cinematheque, and the results were integrated into a single feature-length story. There were seven student directors, one per episode; a producer contributed an extra chapter. Most directors were on the set all the time, making suggestions and trying to fit bits together. (“We fought a lot.”) The remarkable visual consistency—smooth cutting, tight framing, and well-modulated lighting—came from the single director of photography. As the title suggests, some of the tales are based on incidents in the lives of its makers.

The film, presented in Vancouver by two of the directors, Hong Youjin and Kim Taeho, is a lively charmer, with plenty of comedy and pathos. The characters are quickly introduced, and there are nice touches of movie-nut satire. One girl with big spectacles saves all her ticket stubs, takes notes on every movie (I can identify), and is annoyed when a boy drapes his leg over the seat in front of him. The episodes make tactful use of digital techniques, particularly in one shot that fuses past and present through the classic color/ black-and-white disparity.

My Film and My Story wasn’t in the official young-film competition, but Icarus Under the Sun was. For once the ragged style of handheld video justifies itself in a tale of a girl who quits school and heads for Tokyo to work in a seedy mahjong parlor. Haruo rooms with a flighty roommate and her boyfriend, but becomes more attached to the workers in the parlor and the owner, a nearly blind, taciturn man for whom she conceives an almost daughterly affection.

The plot barely rises above anecdote, but it’s continually engaging through its focus on the performance of Abe Saori, one of the two directors. Haruo explains that she is “addicted to walking,” and some of the best scenes involve conversations during late-night wanderings in the bitter cold.

Starting out fairly choppy, the narration accumulates weight and breadth as Haruo becomes engaged in her work. The shots throughout are held rather long, but about halfway through, the scenes start to be built out of exceptionally long takes. When another worker, the boy Aran, takes sick, Haruo calls on him and we get an almost suspenseful treatment of her arrival in his apartment, with him lying almost motionless in a heap in the foreground.

The shot lasts almost four minutes as she comes forward to talk with him. Their subsequent conversation is filmed in a tight, leisurely shot as they eat burgers and explain their backgrounds—virtually the only exposition we get about Haruo’s troubled past.

The dingy look of many scenes carries a documentary conviction that a more polished work would not. And the rough texture is actually the product of patient care. Abe and her codirector Takahashi Nazuki explained that they spent ten months in shooting and two to three months in editing. But it’s no mere technical exercise either, since Abe calls it both a fictional film and a documentary about her experiences. Like her protagonist she spurned conventional schooling and went to Tokyo to live on her own. Rooming with Takahashi, she decided to make the film “to know certain shadows” in her life. Icarus Under the Sun is actually the duo’s second film, and they have already finished a third, the more technically slick Soft-Boiled Egg (Hanjuku tamago.). Another thing about young directors: They have energy.

Expecting

Takashi Miike’s 13 Assassins is not what you might expect. Unlike your typical Miike item, this one throws no curves. It is an old-fashioned, butt-stomping, gut-slashing swordplay movie, with swagger to spare. Adapted from a 1963 film, it’s Seven Samurai plus six, with explosives.

True, there’s a Miike signature moment early on that shows what Lord Noritsugu has done to a woman’s body in his quest for piquant entertainment. But this horrifying scene serves a very traditional purpose: To prove to swordmaster Shinzaemon Shimada (and us) that Noritsugu has failed his duty as a leader and must be assassinated. He isn’t merely brutal. He lives an aesthetic of exquisite savagery. He has turned droit de seigneur into performance art. A massacre, he says with a fetching smile, is fun. He is a handsome monster. We can hardly wait to watch him die—preferably like a dog, in the mud, in agony.

Thereafter all that we want from a chambara flows forth in abundance. Unsurprisingly, the plot is framed by the man-out-of-time motif. Noritsugu’s depraved tastes show that the samurai tradition and the Shogunate government have become decadent. This might be a warrior’s last chance to die nobly—but for what? What deserves a man’s loyalty? Hard times have convinced Shinzaemon that the samurai class must ultimately serve the people. But his old rival Hanbei, Noritsugu’s right-hand man, clings to the notion that the samurai serves his master, unswervingly. Hanbei goes to his death committed to traditional duty. But his commitment is proved unworthy when his lord has a little fun with his severed head.

Miike faced a choice. He could have provided each warrior a vivid backstory, differentiating and humanizing each one as Kurosawa did. Instead, given a two-hour running time, he concentrates on strategy: How can a baker’s dozen of fighters defeat Noritsugu’s troops, which will eventually swell to 200? The solution is to maneuver Noritsugu’s men into a village filled with traps that will give the assassins some advantages—surprise, rooftop ambushes, and a deployment of livestock as ordnance. Things are enlivened by a feral hunter, mocking the samurai code while wielding a mean slingshot. After supplying a sketch of each of the thirteen assassins, Miike spends his energy on action. The muddy, gory battle at the climax lasts forty-plus minutes, and is worth every penny of your admission. Magnet, the genre arm of Magnolia, has picked up 13 Assassins for early 2011 release, and you should start thanking them already.

If Miike surprises by doing something normal, Zhu Wen’s Thomas Mao really does keep you guessing. It’s a pleasure to see a movie in which you can’t imagine what will come next.

At first, things seem to go by the numbers. To a remote Chinese farm comes the artist Thomas, to stay a short while and do some drawing. His wizened host Mao provides bed (after the geese are shooed out) and board (mostly corn on the cob). The trouble is that Thomas speaks no Chinese and Mao speaks no English. Every interchange is a pas de deux of misunderstanding. Thomas generously gives Mao some money. Mao refuses—not, as Thomas thinks, because he’s too proud but because Mao considers the amount insultingly small.

So we seem to have the small-scale cross-cultural comedy, making amusing points about people’s petty differences. Then the ghosts arrive.

At least, they might be ghosts. A phantom swordsman and swordswoman float around Mao’s farm and do battle, ultimately slashing off each other’s arms before disappearing, never to return.

There are aliens too, invading Mao’s cabin with pop-concert glow sticks. They’re totally unexpected, like the warriors, and their visit is even more transitory.

Eventually Thomas leaves, and the film starts over. The second part offers a sort of crazy-mirror image of what we’ve seen so far. Artist becomes model, model becomes artist, dog becomes Doggy. If you like the double-track story of Syndromes and a Century, you’ll probably like Thomas Mao, which is less rigorous but more funny. (The very title is part of the joke.) Zhu, who has reveled in comic byplay in Seafood and South of the Clouds, gives us that rare thing, a movie that is whimsical without being precious. You learn about contemporary Chinese painting in the bargain.

More whimsy, also not overbearing: When Liu Jiayin told me last spring that she was making a movie about a plastic fish, I didn’t know what to expect. The answer comes in the short film 607. Here the ballet of family hands seen in Liu’s Oxhide II becomes more playful. 607 is part of a promotional series of shorts by independent filmmakers, and it’s sponsored by a Beijing hotel, The Opposite House.

Mr. Fish, wielded by Liu’s father, swims around the tub, occasionally flirting with a mushroom provided by her mother. Eventually Mr. Fish is tempted by a hook (the curled finger of Liu herself). Will he fall for it? In all, you have to admire the coordination of three people shifting smoothly offscreen around the tub, each person’s hands sliding out of one part of the frame and popping in somewhere else—somewhere, I need hardly say, fairly unexpected.

PS 9 October: This entry has been corrected from its initial appearance. There I had written that Liu Jiayin’s 607 is one of three films she is making for the series commissioned by The Opposite House. Actually, the entire series consists of three films made by independent filmmakers. 607 is one of those and is complete in itself. Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the correction.

Rumination.