Archive for the 'National cinemas: South Korea' Category

Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

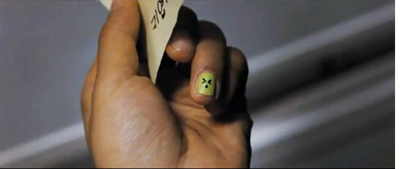

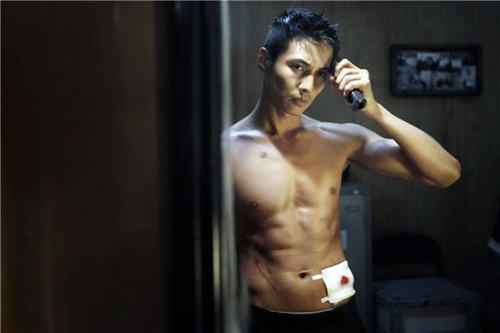

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.

Propinquities

Jinhee Choi, Centre Pompidou, January 2010.

Propinquity: Nearness, closeness, proximity: a. in space: Neighborhood 1460. b. in blood or relationship: Near or close kinship, late ME. c. in nature, belief, etc.: Similarity, affinity 1586. In time: Near approach, nearness 1646. —Oxford Universal Dictionary

DB here:

In any art, tools and tasks matter. From the first edition of Film Art (1979) to the present, our introduction to film aesthetics starts with an overview of film production. How is production organized within the commercial industry, or within a more artisanal mode? What freedom and constraints are afforded within the institutions of filmmaking? How does current technology support or limit what the filmmaker can do? And how do filmmakers explain what they’re doing—not just as personal proclivities but as rhetorical “framings” that lead us to think of their work in a particular way?

Some would call this approach “formalism,” but that label doesn’t capture it. Traditionally formalism refers to studying an artwork intrinsically, as a self-sufficient object. In this sense, our perspective is anti-formalist: We look outside the movie to the proximate conditions that shape its form, style, subjects, and themes.

More literary-minded film scholars have sometimes been impatient with this perspective. Yet in the history of painting and music, it has yielded real advances in our knowledge. It continues to do so in film studies too, as I learned when we came back from Yurrrp to find some books awaiting us. (Kristin has already remarked on the stacks of DVDs that had accumulated.) Among these were books that illustrate the continuing value of situating film artistry in its most immediate context: the creative circumstances, the norms and preferred practices operating within traditions, the rationales that artists offer for their choices. Even better, the books were written by friends, so we have both intellectual and personal propinquity. I have always wanted to use the word propinquity in a piece of writing.

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho).

Jinhee Choi’s The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Gobal Provocateurs is a wide-ranging survey of what some have called the “next Hong Kong”–a popular cinema of brash impact and technical polish, on display in JSA, Beat, Dirty Carnival, My Sassy Girl, and the like. But unlike Hong Kong, South Korea has a strong arthouse presence too, typified by Hong Sang-soo’s exercises in parallel narratives and thirtysomething social awkwardness. Between these poles stands what local critics called the “well-made” commercial film, as exemplified by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder.

Choi, a professor at the University of Kent, mixes analysis of cultural and industrial trends with consideration of crucial genres (notably the “high school film”) and major auteurs. She is the first scholar I know to explain changes in the Korean film industry as emerging from a dynamic among critics, filmmakers, private funding, and government sponsorship. A must, I would say, for anyone interested in current Asian film.

T-Men (Anthony Mann, cinematographer John Alton).

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

Keating scrutinizes the films with unprecedented care, tracing not only cameramen’s distinctive styles but showing that originality was always in tension with the conventional lighting demands of various genres and situtations. Many big names are here—John Seitz, Gregg Toland, John Alton—but the book also examines innovations coming from solid craftsmen like Arthur Lundin, who lit Girl Shy and other Harold Lloyd films. You won’t look at a studio movie the same way after you’ve digested Keating’s richly illustrated analyses.

Both Jinhee and Patrick were students here, and I directed the dissertations that eventually became these books. So of course I’m biased. But I think that any outside observer would agree that these monographs show the value of studying how film artistry and the film industry intertwine.

Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski).

No less sensitive to the interplay of art and business is Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s. The collection is as illuminating as earlier installments have been. How could it not be, with career ruminations from Nora Ephron, John Hughes, David Koepp, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, et al.?

I’ve long found Pat’s Backstory volumes a treasury of information about Hollywood’s craft practices. Every conversation yields ideas about structure, style, and working methods. In this volume, for instance, Richard Lagravanese points out that scenes have become very short; with slower pacing in the studio days, scenes had time to breathe. And after claiming over and over that cinematic narration comes down to patterning story information, I was happy to read Tom Stoppard:

The whole art of movies and in plays is in the control of the flow of information to the audience. . . . how much information, when, how fast it comes. Certain things maybe have to be there three times.

In the studio days this last condition was called the Rule of Three: Say it once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once more for Slow Joe in the Back Row. Some things don’t change.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

The examples run from the silent era (including Lady Windermere’s Fan, a favorite of this site) to Shadowlands, and while music is at the center of concern, speech and effects aren’t neglected. There’s a powerful analysis of the noises during one sequence of The Birds, and the authors pick a vivid example from Kieslowski’s Blue (above), in which Julie is shown listening to a man running through her apartment building; we never see the action that triggers her apprehension.

The authors provide a compact history of sound film technology, including many seldom-discussed topics. For instance, 1950s stereophonic film demanded bigger orchestras and more swelling scores, while separation among channels permitted scoring to be heavier, without muffling dialogue. Throughout, Neumayer and his coauthors balance concerns of form and style with business initiatives, such as the growth of the market for soundtrack albums and CDs (a topic first explored by another Wisconsite, Jeff Smith, in his dissertation book). Once more we can arrive at fine-grained explanations of why films look and sound as they do by examining the craft practices and industrial trends that bring movies into being.

Watching back episodes of the American version of The Office recently, I’ve been struck by the premise it takes over from the UK original. This comedy of humors in Cubicle World is supposedly recorded in its entirety by an unseen film crew. I enjoy the clever way in which the show bends documentary techniques to the benefit of traditional fictional storytelling. The slightly rough handheld framings suggest authenticity, and the to-camera interviews permit maximal exposition by giving backstory or developing character or filling in missing action. The premise that an A and a B camera are capturing the doings at the Dunder Mifflin paper company permits classic shot/ reverse-shot cutting and matches on action.

The camera is uncannily prescient, always catching every gag and reaction shot; even private moments, like employees having sex, are glimpsed by these agile filmmakers. Above all, the camera coverage is more comprehensive than we can usually find in fly-on-the-wall filming. For instance, Dwight is preparing Michael for childbirth by mimicking a pregnant woman and Andy, behind him, tries to compete. Here are four successive shots, each one pretty funny.

Somehow the cameramen manage to supply a smooth cut-in to Andy, and that’s followed by a reaction shot, from a fresh angle, showing Jim watching. The range of viewpoints, implausible in a real filming situations, is often smoothed over by sound that overlaps the cuts, as in both documentary and fictional moviemaking. (See our essay on High School here to see how a genuine documentary uses these techniques.)

Of course I’m not faulting the makers of The Office for not rigidly imitating documentary conditions. Any such blend of fictional and nonfictional techniques will involve judgments about how far to go, as I indicate in an earlier post on Cloverfield. It’s just to acknowledge that TV visuals have their own conventions, and these can be creatively shaped for particular effects. We ought to expect that those conventions would encourage close analysis as easily as film traditions do. Jeremy Butler’s new book Television Style offers the best case I know for the claim that there is a distinct, and valuable, aesthetic of television.

Following his own study Television: Critical Methods and Applications (third edition, 2007) and paying homage to John Caldwell’s pioneering Televisuality, Butler gets down to the details of how various TV genres use sound and image. Butler’s conception of genres is admirably broad, considering dramas, sitcoms, soap operas, and commercials, each with its own range of audiovisual conventions and production practices. His discussion of types of television lighting complements Keating’s analysis; put these together and you have some real advances in our understanding of key differences and overlaps between film and video.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

None of this is to say that artistic norms or industrial processes are cut off from the wider culture. Rather, as becomes very clear in all of these books, cultural developments are often filtered through just those norms and institutions.

For example, everybody knows that in classical studio cinema, women were usually lit differently from men. But Keating notices that often women’s lighting varies across a movie, depending on story situations. He goes on to make a subtler point: there was a greater range in lighting men’s faces. Men could be lit in more varied ways according to the changing mood of the action, while lighting on women was a compromise between two craft norms: let the lighting suit the story’s mood, and endow women with a glamorous look. The fluctuations in the imagery stem from adjusting cultural stereotypes to the demands of Hollywood’s stylistic conventions.

Careful studies like these, alert to fine-grained qualities in the films and the conditions that create them, can advance our understanding of how movies work. Pursuing these matters takes us beyond both the movie in isolation and generalizations about the broader culture; we’re led to examine the filmmaker’s tasks and tools.

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (Jang Sun-woo, 2002).

Wantons and wontons

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!