Archive for the 'National cinemas: South Korea' Category

A masterpiece, and others not to be neglected

About Elly.

DB still in Hong Kong:

I haven’t been slack, honest; I’ve caught several items at the archive and during the first weekend of the Film Festival. I even saw Watchmen, accompanied by rump-shaking Shaw Active Sound. But today let me get caught up with some films I saw in Filmart last week.

I was unimpressed by the picture that launched Filmart, Derek Yee’s Shinjuku Incident. Billed as Jackie Chan’s emergence as a real actor, it features him as a confused illegal immigrant thrown into the Tokyo underworld. His character never made sense to me, and the direction was formulaic: basically pan around a group of actors until somebody says something. Daniel Wu gets to play another maniac.

Less heralded Filmart screenings were much more satisfying. The best, and my favorite film I’ve seen so far this year, was About Elly. It is directed by Asghar Farhadi, and it won the Silver Bear at Berlin. I can’t say much about it without giving a lot away; like many Iranian films, it relies heavily on suspense. That suspense is at once situational (what has happened to this character?) and psychological (what are characters withholding from each other?). Starting somewhat in the key of Eric Rohmer, it moves toward something more anguished, even a little sinister in a Patricia Highsmith vein.

Gripping as sheer storytelling, the plot smoothly raises some unusual moral questions. It touches on masculine honor, on the way a thoughtless laugh can wound someone’s feelings, on the extent to which we try to take charge of others’ fates. I can’t recall another film that so deeply examines the risks of telling lies to spare someone grief. But no more talk: The less you know in advance, the better. About Elly deserves worldwide distribution pronto.

Also worth seeing was A Place of One’s Own, a Taiwanese film that uses imagery of living spaces to explore generational differences. As a young rock singer’s career fades, his pop-star girlfriend’s career takes off. Their fates are intertwined with those of a family who live near a cemetery. The father makes exquisite paper dwellings that are burned during funeral ceremonies, the mother maintains gravesites (and talks to ghosts), while the son launches himself on a real-estate career with the help of a dodgy rich kid. Director Ian Lou (God Man Dog) enhances this network narrative with some clever flashback constructions as well.

My Dear Enemy.

Two films I saw in the market display different ways of using past incidents to explain a story’s present-time crises.

My Dear Enemy, by Lee Yoon-ki, exhibits a striking concentration and dramatic focus. Hee-soo’s boyfriend Cho borrowed $3500 from her before they broke up. Today she has tracked him down and demands it back. She drives him around as he visits various associates—his biker cousin, a high-class prostitute, a rich older woman who seems to be using his sexual services, an unmarried mother—scrounging for money to pay Hee-soo back. Across a day of setbacks both comic and frustrating, we come to learn of their romance and their deeper personalities.

At first Cho seems the classic annoying charming rogue, chattering about the music he likes, pausing to buy flowers and oversweet coffee, flattering every woman he meets, and on the verge of ducking Hee-soo’s demands. Every time he gets out of the car, you think he might bolt. These first impressions, however, get nuanced as we see how he moves easily and even gracefully through his milieu. He seems a loser, but we learn that he is resilient and resourceful. Meanwhile Hee-soo’s righteous determination to get her money back comes to seem something of a desperate effort to close the book on painful episodes from her past.

Lee Yon-ki, who earlier gave us This Charming Girl, is very good at structuring scenes so that we understand every character’s changing attitudes. To get the money, Cho lets his target think that he’s helping out Hee-soo, and at one point he implies that she’s pregnant. As Hee-soo realizes that he’s making her play a part in his drama of self-aggrandizement, she is hurt and ashamed. And Cho’s happy-go-lucky facility in his milieu makes her feel more of an outsider. One scene, in which Cho’s hooker friend calmly insults Hee-soo, is a subtle study in casual humiliation.

Yet Hee-soo’s tenacity wins Cho’s respect. At the same time, while as the day passes into night, Cho emerges as a figure with his own code of honor (he eventually provides a meticulous account of what he’s cost her in the day’s expenses) and even a dream of success that might, the last shot suggests, be fulfilled. Bits of business around coffee, cellphones, flowers, and a broken windshield wiper chart the fluctuations in their relationship concisely. My Dear Enemy is a model of how to make a tight, intimate movie focused on simple incidents that carry almost Hitchcockian tension: Will Cho pay Hee-soo off? Will he slip away and abandon her again? What will we learn next about each one’s past? Like About Elly, this is a character study with an engrossing plot.

More diffuse, I thought, was Ann Hui’s unfortunately titled Night and Fog. It’s a companion piece to The Way We Are, her 2008 study of life in the Tin Shui Wai area of Hong Kong. I offered an admiring account here.

This is the “darker story” Ann promised us at last year’s festival, and it’s based on an actual case. Lee Sum has married a Mainland woman, Ling, and has fathered two daughters with her. He’s on social security and Ling works as a waitress. But Lee is considerably older, and he suspects her of flirting with other men. He becomes insanely jealous, beating her and throwing her and their daughters out. Ling finds happiness in a woman’s shelter, but social services fail her and Lee brutally murders her and the children.

No harm in telling you the ending because the murder is the first thing we see. The film consists of a series of flashbacks, some nested within others, that trace what led up to Lee’s horrendous crime.The plot is presented in the framework of a police investigation, with witnesses to Ling’s life answering questions that pass into scenes from the past. The early flashbacks are quite linear, treating the buildup to Ling’s stay in the shelter and a moment in which she sings a song about a mushroom maiden. Then we plunge further into the past, showing her leaving her provincial home as an adolescent on the way to work in the city. Soon we’re given early moments in Lee’s courtship of her.

One effect of introducing the early stages of their marriage late is to mitigate the harsh portrayal of Lee that has dominated the first half of the film. He seems genuinely in love with Ling, and he rebuilds her parents’ home. Already, however, we glimpse his drunkenness, his sadism, and his aggressive sexual appetites.

On the whole, I’m not sure that this complicated flashback structure serves the film well. At times it is strikingly symmetrical, as when a scene of Lee returning from Shenzhen on the train is followed by a distant flashback of the marriage, and this is closed off by a shot of Ling and her daughters traveling on the same train. At other points, though, the relation between the witness’s testimony and the flashback episodes is arbitrary, with the flashbacks showing scenes unrelated to that witness’s knowledge of the family drama.

It seems to me as well that the power of the events leading up to Lee’s murder of his family is vitiated by the protracted Mainland visits, widening the film’s field of view to life in Sichuan and Ling’s family. Where My Dear Enemy lets its backstory emerge in piecemeal fashion through hinting dialogue, dramatizing every relevant moment in Ling’s past seems to lose some focus.

Likewise, there’s a certain fuzziness about the film’s main thrust. Is it a character study, trying to explain why Lee is violently jealous and why Ling stays with him? The only clear answer I could determine was her sense of indebtedness for his help to her parents. Is Night and Fog then best taken as a critique of the Hong Kong bureaucracy? The social workers are portrayed as indifferent or unable to understand domestic violence. But in that case we need to see more of the mechanisms of decision-making than we do, and then many of the intimate relations of the couple would be extraneous. The battered women’s shelter, while not unblemished, becomes the opposite pole to Ling’s dangerous household, and Huipresents it as a safe space where women can express their feelings spontaneously. But again, this angle on the material seems vitiated by bringing in a public protest against real-estate development of the harbor area—an important issue, but in the context a bit distracting.

The film seems to me to excel in areas that Hong Kong cinema has made its own: extreme emotion and sheer physicality. The violence of Lee’s assaults on his family are terrifying, and Simon Yam’s performance is tremblingly ferocious. Smoking furiously, swigging cans of beer, Yam gives us Lee Sum as a figure on the edge of destruction. He makes even fishing seem an act of aggression. Lee’s incessantly jiggling leg is like the timer on a pressure cooker, and when he sits down with his son from a previous marriage—a sleepy-eyed young pimp—the two of them share the same foot-jiggling tic. In this shot, Hui gives us a diagram of male aggression ready to burst.

If My Dear Enemy trades on suspense, Night and Fog creates dread. One is roundabout, the other more direct; one suggests much, the other shows everything. Two ways, we might say, of making modern cinema.

More, including another Iranian masterpiece, in my next communiqué.

Night and Fog.

A glance at blows

DB here:

Perhaps it came from watching the Odessa Steps sequence, projected in hazy 8mm, on the bedroom wall during my teenage years. Or maybe it was seeing my first Bruce Lee movie in the early 1970s. In any case, at some point I became a connoisseur of action sequences. Eventually I was able to indulge this tendency by writing about Eisenstein, but also by studying Asian action film.

I became convinced that martial arts movies from Japan and Hong Kong constituted as important a contribution to film aesthetics as did the Soviet Montage movement. Through shot-by-shot and even frame-by-frame analysis, I tried to show that these movies were exploring ways that cinema could arouse us kinesthetically. Their use of composition, cutting, color, music, and physical motion was not only beautiful but also engaging on levels that we didn’t fully understand. (Perhaps now that we know about mirror neurons we’re in a better position.) Certain turns in the action make us laugh, but not in derision. We laugh in jubilation, and sometimes out of admiration for sheer audacity. At their most ambitious, these films achieved the physical-emotional ecstasy that Eisenstein found in sharply executed “expressive movement.”

A jolting blur

So it was with a definite sadness that I watched, from the 1980s onward, the tendency of American filmmakers to give up on rendering physical movement with full force. Action sequences became jumbled arrays of short shots and bumpy framings. The clarity and grace of motion seen in classic Westerns and comedies, in the work of Keaton and Lloyd and Ford and Don Siegel and Anthony Mann, gave way to spasmodic fights and geographically challenged chases. At first, the chief perpetrators were Roger Spottiswoode and Michael Bay. Now it’s nearly everybody, and journalistic critics have recognized that this lumpy style has become the norm, even in the generally admired Bourne entries.

Classic Hong Kong and Japanese action scenes were “expressionistic” in the sense that their larger-than-life balletics and aerobatics amplified recognizable (if extreme) possibilities of the human body. The result was a carnal cinema, in which shooting and cutting aimed to enlarge and prolong graceful movement. By contrast, Hollywood action scenes became “impressionistic,” rendering a combat or pursuit as a blurred confusion. We got a flurry of cuts calibrated not in relation to each other or to the action, but instead suggesting a vast busyness. Here camerawork and editing didn’t serve the specificity of the action but overwhelmed, even buried it.

Why is the filmmaker reluctant to face the concrete, moment-by-moment facts of the fight? Maybe it’s fear of censorship, or maybe it’s just lack of interest in physical processes. By contrast, most of the great Hong Kong action directors have been themselves martial artists. To them a fight is a suite of tangible actions and micro-actions. Or maybe the new muddier approach seeks to hide the fact that the action is preposterous. Western audiences don’t like far-fetched action that isn’t comic, but the new action picture is touted as a return to realism. Bond is tough and Jason Bourne’s adventures are “gritty.” Yet realism comes at a price, in this case the loss of bodily movements elegant in their efficiency.

Defenders of the impressionistic approach say that it renders “what the action feels like.” But that would entail that the action feels fast and confusing. To whom? Maybe to a duffer like me, if I were dropped into the melee, but not to trained fighters. Bourne isn’t confused: his senses are alert, and his gestures are economical and smooth. So why render the scene as chaotic and show his gestures in jerky cuts? Any fighter overcome by the sensory overload handed to us would lose big.

The classic Asian approach also tries to make us experience how the action feels, but it starts by taking pains to show how it looks. Hong Kong filmmakers constructed a sequence on a firm foundation, and that meant making each shot impossible to misunderstand. They then built those crisp images into what I called the pause/ burst/ pause structure. This simple pattern, capable of great variation. creates a staccato exhilaration.

How? Here’s a first approximation. The stylistic orchestration of the fight trips off optical, auditory, and muscular responses in our bodies, while the pauses give the movement a chance to echo. Instead of a vague busyness, a sense that something really frantic but imprecise is happening, we get a marked rhythm alternating an exact visceral impact with tingling aftereffects. Eisenstein believed that when we see an expressive movement, we reflexively repeat that movement, albeit in weakened form. After one of these sequences you feel tired, but in a good way. We’ve been given a taste of what physical mastery feels like.

Transport

Compare the action scenes of the first Transporter film (2002) with those of Transporter 3 of this year. The first, directed by Hong Kong veteran Yuen Kwai (aka Corey Yuen), isn’t a patch on his best home-ground work (Ninja in the Dragon’s Den, Righting Wrongs, Yes, Madam!, Saviour of the Soul), but the bigger budget provided by Luc Besson gave him a chance to put Jason Statham through some energetic paces, particularly on the oil-slicked floor of a bus garage.

Yuen, a director who sacrifices even dialogue to pictorial rhythm, is fond of percussive insert shots (e.g., the garage scene’s crackling close-ups of Statham snapping bike pedals onto his shoes) and steep, tight angles that spread all of a fight’s players into a diagrammatic composition.

But Transporter 3, choreographed but not directed by Yuen, has buried precise, bone-whacking action under freeze-frames, superimpositions, ramping, color shifts, and other Tony Scott doodling.

Something more sober but just as nerveless is at work in Quantum of Solace. Here the jabbing handheld work of the Bourne pictures has been replaced by steadier framing and smoother traveling shots, but the hyperkinetic, what-did-I-just-see cutting is still there. Again, I think that the filmmakers are worried about the implausibility of the action scenes and so muffles them by a haphazard handling.

Back to basics

Most discouraging has been the way that many Asian filmmakers have taken up the Hollywood approach. Today’s standard Hong Kong action picture is likely to be as visually and kinetically disorganized as the Hollywood product. That’s why I can recommend, as a palate-cleanser if nothing else, Ryoo Sung-wan’s City of Violence (2006), a Korean film recently made available on DVD from Dragon Dynasty.

It is unapologetically formulaic. Pals in a teenage gang grow up to be gangsters and cops. Our protagonist, a big-city cop, returns to the hometown to discover that the weakest of the old crew has become a sadistic overlord. Fights ensue, culminating in a twenty-minute battle in which the hero and another schoolmate penetrate a restaurant where the villain is celebrating his new status. Thrashing their way through a crowded courtyard, then through a narrow tunnel of dining rooms, and finally into a two-story banquet hall, our heroes confront increasingly skilful fighters and eventually face off against their boyhood friend.

Ryoo keeps the action scenes fairly brisk and inventive. The most impressive early one shows the hero surrounded by a battalion of young thugs in a nighttime boulevard. The teens, in an obvious bow to The Warriors, come dressed in ingenious uniforms and display alarming skills with hockey sticks and baseball bats. As in Hong Kong films, judicious long shots keep us oriented to phases of the action.

Borrowing unashamedly from John Woo’s Better Tomorrow series and countless Japanese swordplay films, City of Violence shows flashes of pictorial wit. The cop and his pal realize they’re confronting a platoon of bodyguards at supper when doors slide open to reveal a tunnel-vision perspective of fighters, blobs of black broken rhythmically by women’s pastel outfits.

The film flaunts vivid color and icy focus in a way that much more expensive Hollywood genre movies, with their brackish palettes and soft edges, mostly avoid. (The realism alibi, again.) Even Ryoo’s use of CGI is playfully pretty, in a way that Casino Royale could be only in its credits sequence. Here the gang lord realizes his old pals are approaching.

I don’t want to oversell this film, but it does show that the classic Asian tradition has not expired. Running under ninety minutes without credits, City of Violence aims at nothing more than telling a familiar story with vigor—along the way making us gape and flinch. In a good way.

For arguments about Eisenstein and expressive movement, see my Cinema of Eisenstein, new ed. (Routledge, 2005). The case for Japanese and Hong Kong action films is made in Chapters 12-15 of Poetics of Cinema, and the pause/ burst/ pause pattern is analyzed in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. There, among other things, I try to give Yuen Kwai his due.

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

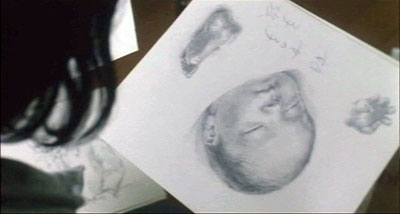

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.

The tact of Hashigushi’s handling is on display in a late sequence. As Shozo struggles out of her depression, her family gathers for what apparently will be her grandfather’s final moments. The adults assemble to discuss the situation while children play in a room behind them. Kanao shows them sketches that they take to be of the father in his final moments.

During their discussion, the adults are distracted by the children shattering an urn in the background.

Here Hashigushi uses staging techniques I’ve discussed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Kanao’s display of his sketch favors us; it is centered and frontal. Then, after blocking the children’s play for some time, Hashigushi reveals it—centered and exposed as the adults in the foreground turn to look.

Then most of the family leaves. Hashigushi tracks in slowly to the mother’s confession of her misdeeds, and he ends the shot with a close-up of Shoko.

In a film in which the camera moves seldom and without much fanfare, this creates a simple, powerful impact and refocuses the drama on the psychologically fragile Shoko.

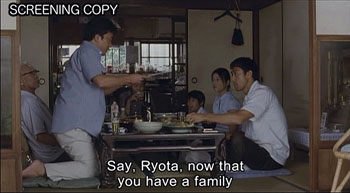

The film I’ve admired most across the festival is, predictably, Still Walking by Kore-eda Hirokazu. It relies on a simple situation. Grandpa and grandma celebrate a son’s death anniversary by a visit from the families of their son and daughter. Across a little more than a day, memories resurface and old tensions are replayed.

Everything unfolds quietly, and the pace is steady: none of the histrionics, both dramaturgical and stylistic, of the Danish Celebration and other psychodramas of dysfunctional families. Still Walking is a classic Japanese “home drama” in the Ozu mold. The conflicts will be muffled and nothing is likely to break the placid surface.

In a stream of vignettes Kore-eda brings each family member to life, displaying an easy mastery in shifting attention from one to another. Gradually he assembles a group portrait of a domineering father, a good-humored mother, a slightly daffy daughter, a son always compared unfavorably to his elder brother, and in-laws striving to be well-received by the grandparents without alienating their spouses. The spirit of Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story and Early Summer, hovers over specifics: a dead brother is invoked, the family poses for a picture, and the patriarch, a retired doctor, has a clinic in his home.

Kore-eda doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves; he’s often overshadowed by extroverts like Miike Takeshi. That’s partly because his is an art of quietness, shown perhaps in its most extreme form in his first feature, Maborosi (1995). At the time I thought it was only one, albeit exquisitely wrought, version of the “Asian minimalism” that sprang up in Taiwan, Japan, China, and even a bit in Hong Kong. I suspect that this trend was largely due to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpieces like Summer with Grandfather, Dust in the Wind, and City of Sadness. A Japanese critic told me that indeed Maborosi was criticized as being too Hou-like.

Now, after After Life, Distance, Nobody Knows, and Hana, Kore-eda has moved to the forefront of Japanese cinema. It seems to me that he maintains the classic shomin-geki tradition of showing the quiet joys and sadness of middle-class life while also plumbing the resources of “minimalist” mise-en-scene.

In Still Walking he works in an engaging, unfussy way. He lets us get to know and like his characters, feeling neither superior nor inferior to them. He builds up his plot more through motifs than dramatic action; a good example is the pop song that the mother loved and that gives the movie its title. The technique, spare but not austere, enforces the relaxed pacing. The film has only around 375 shots in its 111 minutes. While there are plenty of reaction shots and close-ups (the first shot shows women’s hands scraping radishes), some scenes play out in long takes rich in detail.

For example, in a three-minute shot early in the film, most of the family is gathered around a table.

The brother-in-law, a used-car salesman, goes out to the garden to play with the children.

Now the family members discuss the dead brother’s widow, who doesn’t come to family gatherings.

When the father declares that a widow with a child is harder to marry off, he is obtusely insulting his son Ryota’s new wife. Kore-eda marks the disruption with a cut to a reverse angle.

This generates another long take, in which Ryo’s wife Yukari deflates the tension by saying she was lucky to get him. The women then rise and clear the foreground, somewhat as the brother-in-law had by going into the garden. As the family talks, we can see him in the distance helping the kids break open a melon.

Ryo talks about his job restoring paintings. It’s clear that the father disapproves of it, wishing that Ryo, like the deceased brother, had taken up medicine. Kore-eda keeps the garden action as a secondary point of interest by having Ryo glance off occasionally.

But Ryo’s explanation of his job is cut off by the father’s abrupt rise and walk to the doorway, ordering the kids to stay away from one plant.

When the father returns to the table, the nearly two-minute long shot is replaced by a series of singles as Ryo tries to explain his work.

These shots employ one of Ozu’s staging tactics, settling two characters not directly opposite one another but one space apart. The camera seats us across from each one. As a result, the men can be posed frontally, while now we can watch where their glances go—most often, downward. The new setups let us see that the father and son don’t look at each other much.

Instead of moving to these singles right away, as most directors today would, Kore-eda has saved them as a way to articulate the next, more intense phase of the drama. It is arguably a less ostentatious way to raise the tension than the prolonged track inward that Hashigushi uses in All Around Us. (Then again, Hashigushi employs that technique at a climactic moment, while this scene we are still rather early in Kore-eda’s film.) The point is the simplicity and delicacy with which Kore-eda deploys traditional elements of craft.

It wouldn’t be fair to offer a more intensive analysis of this trim work, since it has yet to be widely seen. In the best of all worlds, it will get an American theatrical release.

In all, another wonderful Vancouver festival. See you there next year?

FlicKeR.

Things to like about looking

13 Lakes.

“What I like about looking is how many ways there are to see the same thing.”

Sadie Benning

DB here. Today no extended essay, just some jottings.

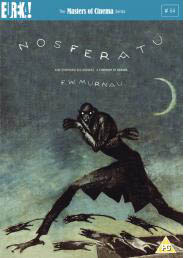

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

A recent batch of Eureka releases:

*Two cult animation items by René Laloux, Gandahar and Les maitres du temps. Fans of Fantastic Planet and the bande dessinée artist Moebius will snap these up, as much for the large booklets as for the discs.

*Then there’s Nosferatu. You say we’ve already got enough? Nope. First, we can never have too many of this, one of the greatest of silent films. Second, this version looks scarily definitive: a two-DVD set with the Murnau-Stifung restoration and the original score, plus a documentary, plus a book including some primary material along with essays by Enno Patalas, Gil Perez, Thomas Elsaesser, and Craig Keller.

*Sticking with Murnau (who directed, some say, in a white lab coat), Eureka offers a double-disc set of Tabu, also from the Murnau-Stiftung and with previously unseen scenes and title cards.

*Finally, there’s Peter Watkins’ Edvard Munch in its long version, with a booklet including a Watkins “self-interview.”

Unbelievably, many more great movies are on the way. Check the catalogue and preview lineup here.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

I have a personal interest. I met Jim when I came to Madison in 1973. He was working on his MFA in film and art, and he was one of four teaching assistants assigned to me. There was Doug Gomery, already an impressive film historian, soon to go on to fame for his work on the US film industry. There was Brian Rose, one of the most alert cinephiles I ever met, and one of the funniest. There was Frank Scheide, already an expert on Chaplin, Keaton, and their peers. And there was Jim, a master mathematician (helpful for computing grade curves) and the only filmmaker in the bunch. Jim and Frank, both serene, had a calming influence on the rather hyper Rose, Gomery, and Bordwell. It was a great team, my Dirty 1/3 Dozen, and I remember our collective grading sessions fondly.

Jim had already made Time and a Half, but his most famous works, starting with 81/2 x 11 (1974), were yet to come. He left Madison and went on to teach filmmaking at several places, settling finally at Cal Arts. I kept in occasional touch with him and his work. He visited our Wisconsin Film Festival with his remarkable, politically charged Four Corners, El Valley Central, and Los. I’ve seen him more frequently in the last few years because turn up at the same film festivals—me as an observer, him showing gorgeous and provocative films like 13 Lakes, 10 Skies, and One Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later.

So the book, edited by Claudia Slanar and Barbara Pichler, is very welcome. It just arrived, so I haven’t had a chance to read it through, but I signal it to all those interested in a filmmaker who has been enthralling and surprising us for thirty-five years. Apart from a career chronology and a complete filmography, it features essays by Julie Ault, Sharon Lockhart, Volker Pantenburg, Dick Hebdige, Amanda Yates, Scott MacDonald, Allan Sekula, Michael Pisaro, Nils Plath, and of course Sadie Benning, a mean hand with Pixelvision. Lockhart supplies lustrous shots of some Wisconsin beer bottles in Jim’s collection.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

The directors honored are Kim Dong-on, Im Kwon-taek, Lee Chang-dong, Kim Ki-young, Park Chan-wook, and Hong Sang-soo. This last volume, edited by Huh Moonyung, includes an homage by Claire Denis and a small essay by me, “Beyond Asian Minimalism: Hong Sang-soo’s Geometry Lesson.”

Books in the series may be ordered here.

Speaking, again, of books. . . The paper edition of Phillip Lopate‘s American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents until Now (The Library of America) has just come out. I found reading the first edition addictive, like eating peanuts and M & Ms. Now we need a second volume including Frank Woods (a critic close to Griffith), Welford Beaton, and other less-known early writers.

In the meantime, the new edition has grown to include an essay on Fincher’s fine Zodiac by Nathan Lee and internet pieces from Stephanie Zacharek (Salon.com) and your obedient servant. I’ve never imagined an essay of mine in a collection that includes my teenage idols Mencken, Macdonald, Sontag, and Sarris, so this volume amounts to a swell early Christmas present. Thanks to Mr. Lopate and Geoffrey O’Brien for all their help.

Speaking, yet again, of books. . . A plug is in order for Scott Higgins’ meticulous, engagingly written Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s, just out from Texas. I sat on Scott’s dissertation committee, and I was impressed by his imaginative research methods (e.g., using Pantone swatches as an objective measure of color hues in movies) and his sensitive attention to the way the movies look. Nobody before Scott has analyzed color in film so carefully. Scott is also attentive to production practices, so filmmakers interested in the history of technology should find a lot to chew on here. Several pages of original Technicolor frames support Scott’s case in graceful detail. No beer bottles, however.

More books from Wisconsin scholars: The above-mentioned Doug Gomery has a new book due out early next year, A History of Broadcasting in the United States. Lea Jacobs’ The Decline of Sentiment: American Film in the 1920s should follow soon. I’ve read the latter already, but both are without doubt worthy of your attention. If you like your American film history at once informationally solid and intellectually daring, you will like these items. Neither Doug nor Lea is a fan of conventional wisdom.

Finally, for fans of Hong Kong cinema: Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai‘s Mad Detective (I filed a note on it from Vancouver) has been a hit in Hong Kong, beating Beowulf. An analog Lau Ching-wan can thrash a digital Ray Winstone any day of the week. Milkyway Image’s boundlessly energetic Shan Ding has set up a Facebook page as a place to chat about movies and, one hopes, to keep us apprised of developments in Mr T’s upcoming remake of Melville’s Cercle Rouge.

Mad Detective.

PS: Just learned about an informative interview with Jim Benning here, with more ravishing shots from 13 Lakes. This entry also includes several other links to web discussions of Jim’s films.