Archive for the 'National Cinemas: Latin America' Category

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

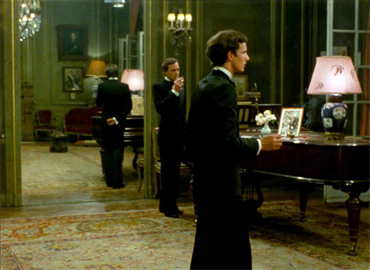

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

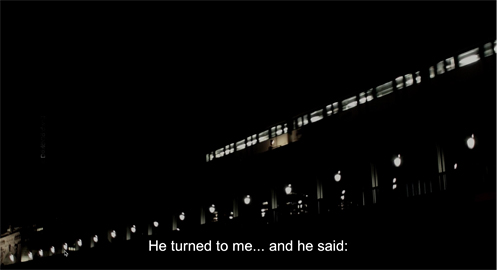

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

Venice 2019: Repremieres

The Spider’s Strategem (1970).

Kristin here:

The policy at the Venice International Film Festival is to show only world premieres of films. Luckily that includes premieres of restored prints of classic films. These form a major thread in the program here, and this year had been particularly rich in older films that have been unavailable or available only in incomplete or poor prints. We have been catching up with some favorites and were introduced to unfamiliar ones.

The Spider’s Strategem (1970)

Back in the mid-1970s, David and I taught Bernardo Bertolucci’s film, which he made directly after the better-known The Conformist (also 1970). Thanks to the New Yorker print, we came to know it well, and when we wrote Film Art: An Introduction, an example of it went in and has stayed in. David analyzed the film’s storytelling principles at length in Narration in the Fiction Film.

The film came out in VHS versions in the US and UK, both out of print, but it never was released on DVD or Blu-ray. Now it returns in a stunning restoration from Fondazione Cineteca di Bologna and Massimo Sordella. (The restored version is out on Blu-ray in Japan, but without English subtitles.)

The plot involves a young man, Athos Magnani, who returns to the village where his father, who shares his name and appearance, gained a reputation as a bold leader of a small resistance group during the 1930s. He was also mysteriously murdered. The father’s mistress, Draifa, urges his son to stay and investigate the crime, and, it is hinted, to take his father’s place in her bed.

Young Magnani does investigate, but he quickly becomes uncertain as to which villagers were his father’s friends and which his enemies. He also finds himself targeted with threats of violence. Flashbacks mix scenes of past and present with no attempt to differentiate them via period props, changing ages, or stylistic contrasts. The ambiguities, which continue to the end, are not surprising, given that the literary source was a Jorge Luis Borges short story.

Whether or not one enjoys the teasing plot, the visuals are enough to provide delight. The cinematography was done by two major Italian cinematographers: Franco Di Giacomo (The Night of the Shooting Stars, Il Postino) and Vittorio Storaro, known for his bold use of color (Dick Tracy, Tucker: The Man and His Dream, and Tango). The result (see top) is like a blend of classical paintings and an Italian fruit stall.

Now all we need is a Blu-ray release worthy of the print shown here.

Maria Zef (1981)

This was Italian director Vittorio Cottafavi’s penultimate work, made after he has worked almost exclusively in television since the beginning of the 1960s. It has a pleasantly old-fashioned look, perhaps not too surprising in that Cottafavi says he conceived it in 1938, two years after the source novel appeared. He was not able to make it until 1981, when it was seen a project local to the Friuli region of northeastern Italy.

Some internet sources list it as a TV series, but IMDb and others treat it as a film. Certainly it looks like a film and seems to have no obvious pause points. But it was produced by RAI and was shot in the TV-friendly Academy ratio rather than the wider formats that were standard by the 1980s. (While I was watching it, I thought of it as a much earlier film and was surprised to find that it was made so late.)

Maria, an adolescent girl, is traveling with her irrepressible younger sister Rosute and her dying mother. They carry a cart full of domestic implements to sell. The two are taken in by their uncle, Barbe Zef, who made the spoons and other wooden housewares that the trio had been peddling. He’s a gruff fellow, and violent when drunk. Under the influence, he rapes Maria and tries to stifle her subsequent resentment as if his attack had been just a natural impulse.

The film was shot on location in the Italian Alps (above). The region of Friuli will be familiar to many film scholars and buffs who have traveled there for the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” silent-film festival in Pordenone.

The restoration was done by Rai Teche. With luck, the new print will travel abroad and introduce Cottafavi, an Italian favorite, to broader audiences.

[September 10: Thanks to blogger Manfred Polak for providing further information on Maria Zef. He provides a link to a brief piece on the film at the Cineteca de Friuli website. This piece (in Italian) says the film will play at the I Milleocchi festival in Trieste, 13-18 September 2019. The Cineteca also plans a DVD release with numerous supplements. Its earlier release of Vito Pandolfi’s Gli ultimi had optional English subtitles, so perhaps the Maria Zef DVD will as well.]

Mauri (“Life force,” 1988)

This restoration from the New Zealand Film Commission and Park Road Post Production should make available a nearly forgotten classic of New Zealand cinema. It remains the only New  Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

Zealand feature with a Māori woman, Merata Mita, as sole director. (In 1972, To Love a Māori had been co-directed by the husband-wife team Raimi and Rudall Hayward.) Mita had previously made the first feature-length documentary by a Māori woman, Patu! (1983). Much of her career was devoted to documentary filmmaking.

The plot centers largely around an interracial love triangle. Māori woman Ramari is loved by Steve, a white farmer who was schooled alongside Māori children and retained Māori friends as an adult. His father, however, is a rabid and apparently crazy racist who tries a variety of pranks, some violent, to break up the match. Ramari loves a Māori man, Rewa, who harbors a dark secret that prevents him from marrying her.

This drama plays out against the intertwined doings of the family and circle of friends headed by the matriarch Kara. She tries to instill traditional values into her children, grandchildren, and the various troubled people she has treated as her own offspring. The film is set and shot in a tiny, declining village, Te Mata, in the East Cape area of the North Island, south of the now-thriving Hawke’s Bay winery region.

According to the biographical page linked above, “Mita said she had consciously rejected Pākehā traditions of storytelling and embraced a layered approach, in keeping with the strongly oral traditions of Māori. She told writer Cushla Parekowhai: “These are differences that Pākehā critics don’t even take into account when they’re analyzing the film.” Pākehā is the Māori word for white people.

There are rare films, and here I think of Charles Burnett’s To Sleep with Anger, that are entirely set in a specific non-white culture and make no attempt to explain that culture to a white audience. Clearly Mita was trying for the same approach. Her film met with some criticism for not following mainstream conventions of film narrative. Nevertheless, like To Sleep with Anger, Mauri draws in viewers with its drama and appealing characters. Today audiences with a greater openness to other cultures will most likely greet this restored version with greater sympathy and appreciation.

Death of a Bureaucrat (1966)

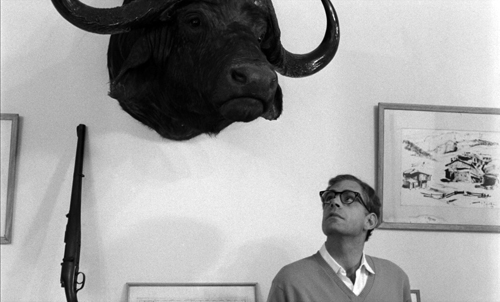

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea is undoubtedly Cuba’s most famous and revered director. Even those with the most passing knowledge of Cuban cinema will know such titles as Memories of Underdevelopment (1968) and Strawberry and Chocolate (1993). Death of a Bureaucrat is another familiar title, restored by the Academy Film Archive and the Cinemateca de Cuba. The screening was introduced by our old friend Joe Lindner, Preservation Officer at the Academy Archive.

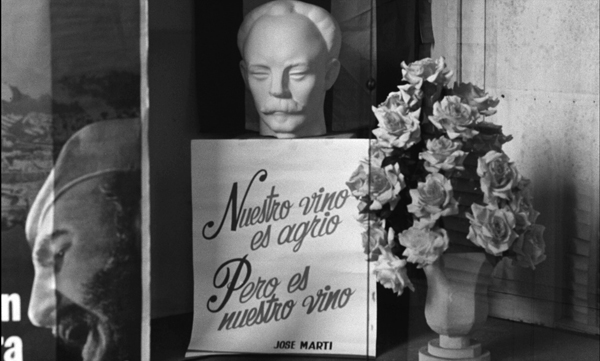

The film is essentially a slapstick farce on a rather unlikely topic, the burial and reburial of the titular bureaucrat. He was a man who distinguished himself by inventing a machine to mass-produce the white busts of political leaders which stand in every government office in Communist countries (and which resemble the bust on the bureaucrat’s tombstone, above). The plot, however, is set off when it is discovered that as a tribute to such a genius, the dead man’s work card has been buried with him, and his widow needs it to receive her benefits.

The rest of the film is a series of escalating efforts by the man’s son to track down the exhumation order which the cemetery officials demand if they are to be able to rebury the body after the card is retrieved. Numerous stamps, signatures, and forms are required, all of which can only be provided by a single person–naturally different in each case. The hero becomes increasingly desperate and begins to try stealth, slipping into an office after closing hours and smuggling his father’s coffin into the graveyard to rebury it himself. All the while the grieving widow gathers all the ice her friends and neighbors can supply to prevent the body, kept at her house, from deteriorating.

The action is amusing enough, including one scene where a hearse is revealed to have a small plastic skeleton dangling from its rear-view mirror. The action does become somewhat repetitious and drawn-out, and one gets the feeling at times that the humor is perhaps aimed at an uneducated audience of workers and peasants, comparable to the Socialist Realism imposed upon filmmakers in the Soviet Union after the 1920s.

It’s interesting that such criticism of the workings of government would be permitted, and yet bureaucratic red tape seem to have been a somewhat safe target for Communist filmmakers, especially if presented as a sort of holdover of bourgeois practices. In the 1920s the Soviets had My Grandmother (Kote Mikaberidze, 1929) and The State Functionary (Ivan Pyriev, 1930), and Death of a Bureaucrat somewhat recalls them.

Extase (1933)

Each of the three years we have visited the Venice International Film Festival, there has been a preliminary evening where a restored early film has been shown. The first year saw the restored Rosita, the second Der Golem, both with orchestral accompaniment. This year there was an early Czech sound film, Gustav Machatý’s Ecstasy.

Having see the film only in the incomplete version that circulated in 16mm in the US for many years, I must say that I had not been impressed. The new restoration by the Národni filmový archiv, with much support from other archives, is a very different film indeed.

The story makes more sense now. It begins with the heroine, played by Hedy Kiesler-Lamarr (as she was then) as a young women who marries a wealthy older man. He turns out to have little interest in passionate love, and she is left on her own to be seduced by a young engineer working on a project near her husband’s estate. The film became famous for its scene of the heroine swimming nude, as well as her first, explicit for its day, love scene with the engineer.

The melodrama works its way out, with the rich man killing himself and the heroine, feeling guilty, leaving her lover. At this point, in the restored print, an abrupt switch to a lengthy sequence shows the engineer returning to work, with a joyous celebration of labor depicted in an imitation of Soviet films of the era. This incongruous ending to the plot comes quite unexpectedly, creating a film very different from the versions available hitherto.

Extase remains a less than wholly satisfactory film, but it now reveals its mixture of various influences of the era: the subjectivity of French Impressionism, the soft style of cinematography from the silent era, and in its ending, the propaganda and montage construction of Soviet cinema. Like Genina’s Prix de Beauté (1930), it’s an early-sound effort to preserve the aesthetics of mature silent cinema.

The evening definitely provided a new, startling version of a hitherto mutilated classic.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for the invitation for David to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

Our collaborator Jeff Smith provided a video analysis of another Alea film, Memories of Underdevelopment, for the Criterion Channel. He discusses it in this May blog post.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

September 10: Thanks to Hamish Ford and Lee Tsiantis for information concerning The Spider’s Strategem‘s releases on VHS and Japanese Blu-ray.

September 18, 2019: Thanks to Gareth McFeely for corrections on dates and spellings in the section on Mauri.

Mauri (1988).

Politics and subjectivity: MEMORIES OF UNDERDEVELOPMENT on the Criterion Channel

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).

Jeff Smith here:

Early last week, the Criterion Channel posted the latest in our series of “Observations on Film Art.” It was my turn at the plate with a video essay on Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s Memories of Underdevelopment. The film has long been a personal favorite due to its formal and political complexity. If the aphorism “the personal is political” rings true for you, then you owe it yourself to watch Memories of Underdevelopment. It is a post-revolutionary culture’s most fully realized depictions of the survival of apre-revolutionary mentality.

A Third Way for Third Cinema

Hour of the Furnaces (1968).

“Toward a Third Cinema,” the 1969 manifesto written by filmmakers Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, remains an important touchstone in the history of global film culture. It captures the militant spirit that characterized post-colonial activism in the late sixties and early seventies. At one point, Solanas and Getino describe the camera as an “inexhaustible expropriator of image-weapons” and the projector as a “gun that can shoot 24 frames per second…” (For the record, that less than a quarter of the speed of an M134 MInigun, which fires at a rate of 100 rounds per second.)

As advocates for the vital role guerrilla filmmaking could play in anti-imperialist struggles, Solanas and Gettino explicitly opposed “third cinema” to more established modes of film production. Of course, the big enemy was Hollywood. It represented a form of commercial cinema that was inextricably linked to the ideology of American capitalism.

More surprisingly, though, Solanas and Getino also condemned European art cinema and its attendant emphasis on individual personal expression. Although art cinema represented a step forward in terms of its attempt to create a non-standard language, it remained “trapped inside the fortress” in Jean-Luc Godard’s words. For Solanas and Getino, the French New Wave and Brazil’s Cinema Novo opened up new aesthetic possibilities. They offered the brio and rebelliousness of youth, yet fit neatly into established commercial distribution networks as the “angry wing” of a capitalist, bourgeois society.

Solanas and Getino practiced what they preached, however. Their ambitious 4-hour agit-prop documentary The Hour of the Furnaces remains a prototype of third cinema practice. The film is a collage of contrasting images and sounds. These juxtapositions often involve the kinds of associational editing and montage principles that Soviet directors like Dziga Vertov and Sergei Eisenstein used in their work. At one point, Solanas and Gettino intercut cattle and sheep being slaughtered on the killing floor of a meatpacking plant with ads for various products originating in Western capitalist societies. (See below and above.)

The comparison was about as subtle as the sledgehammer used to kill the cattle. But the message was clear. The global success of American products, like Chevrolets, depended upon the violent suppression of “underdeveloped” populations.

Memories of Underdevelopment’s critique of post-colonialism is no less incisive, but it’s much less didactic. At first blush, Alea’s film seems to be the kind of European-influenced art cinema that Solanas and Getino explicitly reject. Indeed, Alea even self-consciously gestures toward this tradition through his explicit citation of French New Wave films, like Hiroshima Mon Amour. These allusions are reminiscent of the kinds of cinematic quotations that Godard and Francois Truffaut embedded in their own films.

Moreover, Alea also creates the kind of depth of narration in Memories of Underdevelopment that became strongly associated with art cinema’s emphasis on subjective realism. Throughout the film, Sergio’s thoughts and feelings on the current state of Cuba are given to us via voiceover narration. Many of Sergio’s observations function as ongoing commentary on the symptoms of “underdevelopment” that define contemporary Cuban society. For instance, over shots of downtown shops and boutiques, Sergio notes that Havana is often called the “Paris of the Caribbean.”

Such a descriptor seems a double-edged sword. The comparison to Paris is a way of praising the vibrancy of Havana’s cultural life, its bookstores, museums, cinemas, and modern department stores. Yet the qualification “…of the Caribbean” highlights its isolation from true taste-makers and fashionistas in New York, London, and Paris. For anyone who doesn’t live there, Havana is, at best, a playground for rich tourists from Europe and America.

As a member of the Cuban intelligentsia, Sergio often seems an unusually perceptive social critic. Yet Alea’s creation of such a strong alignment with Sergio seems designed to test the viewer’s moral and political allegiance. As a repository of pre-revolutionary attitudes, Alea’s characterization of Sergio encourages us to ask why Havana should aspire to be Paris in the first place. In a society that seeks to eliminate class distinction, why would one strive for such elitism no matter how rich and storied its culture may be?

In employing a device that often fosters sympathetic engagement with characters, is Alea just as “trapped inside the fortress” as French New Wave directors are? Actually, Alea also seems determined to turn the purpose of character alignment on its head.

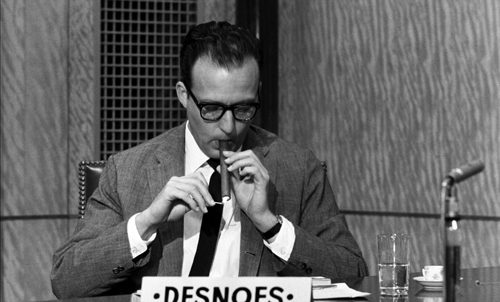

As an intellectual, Sergio possesses a great understanding of Cuba’s relation to the rest of the world, but he seems determined to ask the wrong questions about its future. Therein lies the character’s great tragedy. As novelist Edmundo Desnoes observes, “His irony, his intelligence, is a defense mechanism which prevents him from being involved in the reality.” There is no place outside the palace gates for those like Sergio. Yet in probing his place “inside the fortress” Alea also shows how it rots from within.

By turning the camera’s gaze inward, Alea navigates a path between the agit-prop documentary of Solanas and Getino and the formal adventurousness of an art cinema director like Chile’s Raúl Ruiz. He set out to examine the vestiges of bourgeois thinking in Castro’s Cuba, using Sergio as a “litmus test” for Cuban audience’s political sensibilities. If you find yourself sympathizing with Sergio, seeing him as a victim of the revolution…. Well, then you better check yourself before you wreck yourself. In posing such a challenge, Alea pulls off a pretty neat trick. He manages to create a “third way” in third cinema by merging the polemical aims of agit-prop with devices and formal structures of the art film.

The Portrait of the Artist as a Young Cad

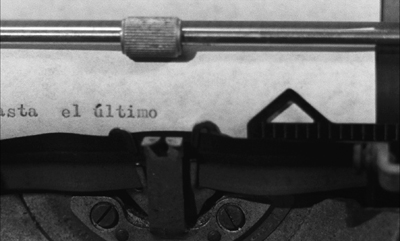

In a gesture that displays both self-consciousness and hubris, Edmundo Desnoes, the author of the novel that served as the source of the film, cast his hero as a writer. Although Alea changed much of Desnoes’ original story, this one small detail was something he preserved in his adaptation of the book. Indeed, just after Sergio has said goodbye to his wife and parents at the airport, we see him sitting at a typewriter. The sentence he writes – “All those who have loved and fucked me over up to the last moment have already gone.” – indicates both his anger in the moment and that his writing has more than a trace of autobiography.

Sergio’s status as a writer encourages the viewer to see him as a surrogate for both Desnoes and Alea. This possibility is even reinforced in a scene where Sergio attends a roundtable discussion of “Literature and Underdevelopment” where Desnoes is featured as one of the panelists.

If Sergio truly is a surrogate for the filmmakers, then Alea shows some real guts in centering his film on an alter ego that is both politically reactionary and sexually predatory.

It is a mark of the film’s complexity that Sergio has certain very attractive traits even though he emerges as a thoroughly unlikeable cad. He is smart, cultured, and good-looking, for example. But he is also passive, cynical, and snobbish.

The dimension of Memories of Underdevelopment, however, that most clearly reveals Sergio’s corruption and moral rot involves his various relationships with women. Alea develops this idea throughout the film in terms of a Pygmalion motif: Sergio seeks to remake his romantic partners in the image of his first love, a German girl named Hanna.

In flashbacks, we learn that Sergio taught his first wife how to talk and dress, how to approximate a downmarket version of European elegance. Similarly, when Sergio initiates a romance with Elena, we see him taking her to bookstores and museums, trying to instill in her some appreciation for art and literature.

Sergios’ European ideals even pervade his sexual fantasies. After looking at an image of Botticelli’s Venus, Sergio imagines his housekeeper, Noemi, lying naked on his bed in a similar pose.

Similarly, when Noemi describes her Christian baptism to Sergio, he imagines it in images that seem culled from a hack romance novel. They embrace in a swoon, with their eyes locked, all wet clinging fabric and raging hormones.

Shot in slow motion, the episode is also accompanied by Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, a concert piece so familiar to most audiences that its inclusion borders on cliché.

It would be one thing, however, if Sergio’s sexual peccadilloes remained in the realm of harmless fantasy. More often than not, Alea depicts Sergio’s relations with women as episodes of exploitation and mental cruelty. A flashback to Sergio’s adolescence implies that the psychological roots of this misogyny lies in his first sexual experience as he and a school chum visit a brothel.

The transactional nature of the encounter is replicated in Sergio’s relationships later in life. After Sergio splits with Hanna, he marries Laura and is given a cushy job in the family business. He also lures Elena up to his penthouse with the promise of his ex-wife’s old clothes. In each instance, Sergio’s sexual or romantic relations with women are based on some notion of recompense: cold hard cash with the prostitute, the reward of a job with his wife, and haute couture with Elena, his new conquest.

As before, the exploitative undertones of Sergio’s relationships with women are reinforced by the film’s style. Sergio’s initial meeting with Elena is handled in a series of long tracking shots representing his optical point of view.

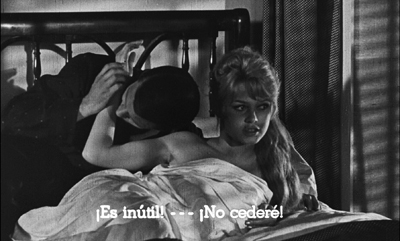

With his creepy pickup line, Sergio seems more of a stalker than a paramour. The troubling implications of this first encounter become more explicit midway through the film when Sergio literally chases Elena around his bedroom. The narrative rhyme with the earlier scene is made evident in Alea’s mobile long take, which once again represents Sergio’s visual perspective. Elena flirts coquettishly, sticking out her tongue at the camera.

But her discomfort in the situation becomes evident in her attempts to rebuff Sergio’s advances. Like the film’s use of voice-over, the moving pov shots spatially align the viewer with Alea’s unlikeable protagonist even as it implicates the audience in his victimization of Elena.

Later, when Sergio is put on trial for sexually assaulting Elena, he becomes the object of the camera’s unrelenting look along with the other petitioners. Here Alea uses a variant of the previous style. The longish takes remain. But where the previous shots used movement to suggest Sergio’s brazen advances toward Elena, the camera’s stasis within the courtroom reflects the perspective of the tribunal hearing the case. Alea cuts quite freely around the space. Still, he always returns to static close-ups of Sergio, Elena, her mother, her father, and her brother as they respond to the questions of offscreen interlocutors.

The scene proves to be the biggest challenge to the viewer’s allegiance with Sergio. He affects the demeanor of someone wrongfully accused. Yet, although the act itself is elided, Elena’s protestations beforehand and her tears afterward suggest that Sergio is probably guilty of the crimes for which he is accused. His voice-over, however, reveals his resentment toward the entire proceedings. The matter of his guilt or innocence is immaterial. What truly angers Sergio is the fact that someone of his lofty station endures treatment more suited to a common crook. He claims that he would never have faced charges during the Batista era. Sergio blames his ordeal on Cuba’s new political landscape. The judgment of his actions is more a matter of proletarian revenge rather than anything he has done.

It is easy to imagine some viewers feeling a pang of sympathy for Sergio. Jurisprudence often includes the presumption of innocence and Alea’s handling of the incident with Elena is ambiguous enough to have certain doubts. Moreover, Sergio has been impoverished by the government’s seizure of his property, something that makes his anger at Elena and her family seem more reasonable.

But what is especially striking in Sergio’s voice-over is the sense of entitlement he displays based on his previous social position. Alea seems to count on the fact that Cuban audiences in 1968 will recognize Sergio’s condescension as a symptom of pre-revolutionary ideology. His previous wealth, his education and culture, his status as an artist all sanction his satisfaction of his desires, even if that means taking the virginity of an 18-year old girl. In his characterization of Sergio, Alea not only reflects the broader influence of the French New Wave. He also revives a classic character type of French literature and cinema: the Parisian roué.

Mr. Schwitters Meets Mr. Alea: Mixing Modalities in Memories

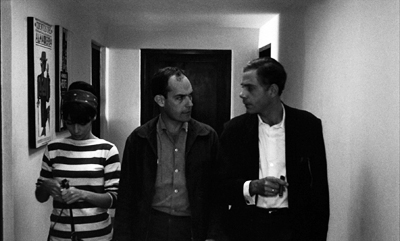

The most oft-quoted line in Memories of Underdevelopment is not something said by Sergio, Elena, or even Sergio’s brusque friend, Pablo. Instead it is uttered by Alea in a director cameo. He appears in a scene where Elena performs in a screen test at ICAIC, Cuba’s central institute of film production. Alea (center, below) shows Sergio and Elena some of his work in progress, saying, “It’s a collage. A bit of this and a bit of that.”

Most critics have noted both the self-consciousness of the moment and its layers of meaning. The footage that Alea screens is made up of scenes cut out by Cuban censors under the Batista regime. It offers a fairly dismal portrait of Cuban film history as something mostly comprised of titles imported from other colonial empires, like the Brigitte Bardot vehicle Une parisienne. This is precisely the kind of cinematic legacy that Alea and other Third Cinema directors set out to counter.

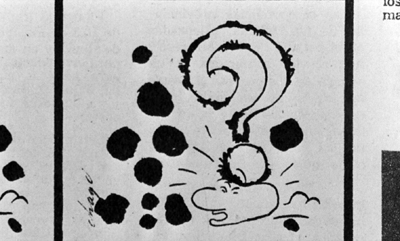

Alea’s description of his film as a collage also has been interpreted as a clue as to how one should view Memories of Underdevelopment itself. More specifically, his comment captures some sense of the film’s complex visual texture, its mix of still photographs, television clips, newspaper headlines, and even comic strip panels.

It also describes the way Alea embeds documentary footage within his portrait of Sergio as a disaffected intellectual. To some extent, this strategy is simply a continuation of Alea’s digressive approach to narration. These interpolated documentary passages fit a larger scheme that also shows fragments of Sergio’s consciousness in fleeting fantasy images and elliptical flashback sequences. Yet these segments of Memories of Underdevelopment also sharpen its political edge. In effect, Alea injects the agit-prop spirit of The Hours of the Furnaces into his “second cinema” character study.

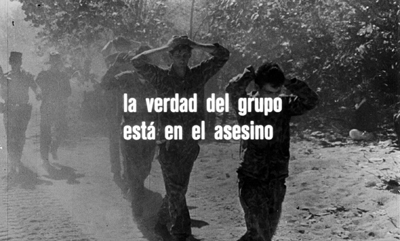

Consider the segment entitled “The Truth of the Group is in the Murderer.”

It is motivated as Sergio’s description to Pablo of the book he is currently reading. But it uses photographs and newsreel footage to explore the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs invasion and the system of political repression and torture that existed under Batista. The title hints at the larger ideological point of the sequence, namely that the regime’s institutional framework served as a means of displacing and shifting criminal culpability away from its individual members. As a member of the bourgeoisie, Sergio is implicated in this dialectical arrangement between the individual and the group insofar as each part of it gives meaning to the whole.

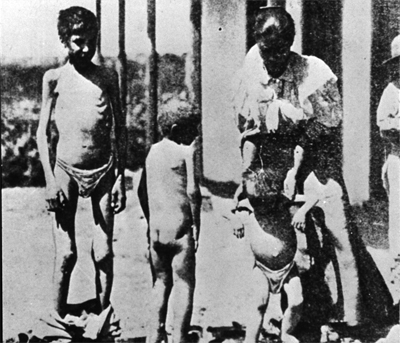

In a scene where Pablo gets his car ready for inventory, Sergio’s mind begins to wander. Alea then cuts to a series of still photos depicting hunger and starvation in Latin America.

In his voiceover, Sergio notes that the death toll from malnutrition exceeds the combat deaths of World War II. The sequence suggests Sergio’s insight into the problems of underdevelopment under capitalism. Alea’s imagery poignantly illustrates the disproportionate impact of such deprivations on society’s most vulnerable members, its children. This mini-documentary in Memories pointedly rebukes the colonialist regimes still present in Latin America by highlighting the cruel effects of such economic exploitation by First World powers.

Similar sequences pop up in the episode labelled, “A Tropical Adventure.” The title refers to Sergio and Elena’s visit to Ernest Hemingway’s former home in Havana, which had been turned into a museum.

A series of photos shows Hemingway’s involvement in Spanish politics, particularly the civil war of the 1930s. A second series of photos depicts Hemingway’s relationship with his longtime servant Rene Villarreal. In his voiceover, Sergio hints that their master-servant relationship captured some of the vagaries of American imperialism. Sergio concludes that Hemingway must have been unbearable.

Sergio’s voice-over during these sequences offers one of the clearest statements of his character’s dualism. He conveys sympathy with Villarreal as a fellow Cuban and recognizes that Hemingway’s paternalism is itself an expression of colonialist ideology. Yet Sergio also seems to identify with Hemingway’s social position given his elite status as a rentier and aspiring writer. His trenchant observations about Hemingway’s relationship with his servant is an unwitting acknowledgement of how easily he could slip into the shoes of the great American author and adventurer.

In the battle for Sergio’s soul the “great white hunter” wins out as we see him hiding from Elena until she just gives up and walks away. Sergio’s condescending treatment of Elena is merely the flip side of the imperialist dialectic expressed by “the faithful servant and the great Lord. The colonialist and Gunga Din.”

Memories’ political sophistication largely derives from Alea’s sensitive treatment of his protagonist’s inner conflict. As a remnant of a previous historical moment, Sergio’s jaundiced perspective suggests that life under the Castro regime has simply substituted a new set of problems for life under the Batista regime. Indeed, for many viewers circa 1968, Alea’s look back at the era between the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban missile crisis might seem an endorsement of his hero’s nihilism and fatalism. Such was the case for several U.S. film critics who Alea disparaged later, claiming that their identification with Sergio caused them to mistakenly privilege the depiction of the artist’s self-interest over the needs of Revolution.

As Alea wrote more than a decade after Memories of Underdevelopment was released, “In Cuba, the Revolution is in power. This means that the conditions of struggle have changed.” Sergio’s struggle to find his place within post-Revolutionary Cuba becomes a metaphor for struggle itself. It is easy to celebrate the moment of triumph when a nation overthrows its oppressors. But a society’s problems don’t just disappear when you have regime change. Memories is the rare film that confronts the challenges faced in the aftermath of any revolution. It takes a hard look at the difficulties in remaking both a society and culture caught in the shadows of two global superpowers: the US and the USSR. In Alea himself put it:

It is to the spectator that the film should reveal the symptoms of possible contradictions and incongruities between good revolutionary intentions – in the abstract – and a spontaneous and unconscious adherence to certain – concrete – values belonging to bourgeois ideology.

Sergio simply becomes the vehicle through which Cuban audiences were encouraged to consciously grasp their own contradictions.

Alea’s insights here attest to his remarkable achievement in Memories of Underdevelopment. By exploring Cuba’s travails after Castro’s seizure of power, Alea knew that First World audiences might misinterpret the film. They might even use Memories to affirm their own imperialist identity. Yet this was not a design flaw. Instead, the film’s vulnerability would also turn out to be its greatest strength among domestic Cuban audiences. Alea’s use of cinematic devices to convey subjectivity imparts a simple but powerful lesson: the Revolution may be over, but revolutionary struggle never ends.

Thanks to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and the whole Criterion team for their superb work. Also thanks to our colleague Erik Gunneson.

The text of “Toward a Third Cinema” is widely available on the Internet, as here.

The most useful resource for information on Memories of Underdevelopment remains the volume in Rutgers Films in Print series. The book contains a reproduction of the continuity script, a reprint of Edmund Desnoes’ original novella, contemporaneous reviews, and Alea’s own reflections on the film some twelve years after it was released.

The film was rereleased in 2018 after undergoing a 4k restoration. Reviews can be found here, here, here, and here. An interview with director Tomas Gutiérrez Alea can be found here. An excellent overview of Alea’s career in its entirety can be found here.

Here’s a complete listing of our Observations series on the Criterion Channel. Our installment on Hiroshima mon amour provides an intriguing comparison to this entry.

Memories of Underdevelopment (1968).