Archive for the 'National cinemas: Middle East' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival 2022: A return to the theaters

Hit the Road (2021).

KT here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival ended last week. This was the first in-person festival after one cancelled (2020) and one presented through streaming (2021). Given David’s health situation, I was not able to attend many films, but here are some of the highlights that I caught.

Wisconsinite David Koepp visited the festival, bringing two films he scripted, Kimi (Steven Soderbergh, 2022) and Death Becomes Her (Robert Zemeckis, 1992), as well as one that inspired the former, Sorry, Wrong Number (Anatole Litvak, 1948). David and I had already seen Kimi on streaming, but I jumped at the chance to see it on the big screen. The sell-out crowd was utterly enthralled throughout, and David K. charmed them during an all-too-short Q&A session. I won’t say anything more about it, since David B. has blogged about it. I did enjoy two Middle Eastern films and the new Claire Denis. (Not the one about to be in competition at Cannes. The woman is certainly cranking them out.

Amira (2021)

In 2017, the Wisconsin Film Festival showed Mohamed Diab’s extraordinary Clash (2016), an epic restaging of the 2013 riots that brought down the Muslim Brotherhood government, all observed by a group of prisoners in a police paddy-wagon. I was excited to see that this year’s festival included Diab’s next film, Amira.

The new film is quite different from Clash. While that showed a cross-section of Cairo participants in the riots or simply bystanders swept up by the police, Amira centers on a personal drama of an extended family living in an unidentified occupied Palestinian area of Israel. (The film was shot in Jordan, so local landmarks would be no help in figuring out exactly where the family lives.) Amira’s parents have never consummated their marriage, since the husband, Nawar, is imprisoned for life, and his wife Warda became pregnant through semen smuggled out of the prison. Amira is officially the daughter of Nawar’s brother, but she is fiercely devoted to Nawar, going through elaborate security procedures to visit him in prison.

The plot gets going when it is revealed that Nawar has a genetic abnormality that rendered him sterile from birth. The close-knit family descends into vicious arguments and accusations, with Warda being suspected of infidelity, the men on both sides of the family indignantly refusing to take DNA tests, and Amira concocting wild schemes to protect both her parents and ultimately take revenge on the person deemed guilty of bringing disgrace on the family.

Despite the impressive shot of Amira and her boyfriend against the city (above, a cropped image from the widescreen film), the film opts for crowded interiors most of the time–though not as limited as the paddy-wagon of Clash. Small apartments, narrow alleyways, and above all the visits to the prison create a claustrophobic atmosphere where nature and the bustle of society in the city are largely eliminated.

The prison scenes involve extended shot/reverse-shot conversations between Nawar and his family members through a glass barrier.

Shot with telephoto lenses, the scenes use shallow focus to concentrate our attention on the central characters. At the same time, though, reflections and planes of action out of focus create a sense of cramped space and similar conversations going on in a cramped room. Here Nawar suggests that he and Warda have a second child, since an opportunity to smuggle out some of his semen again. Amira’s delight at the idea and Warda’s doubtful expression set up the disastrous revelation to come: that Nawar cannot in fact be Amira’s father.

Checking Diab’s filmography on IMDb, I was surprised to learn that he is the main director on the current Marvel streaming series, Moon Knight. I had been completely ignoring this show, since I have little to no interest in the MCU. I did notice some comments by Egyptological friends on Facebook that the hieroglyphic texts were authentic (an important chapter from the so-called Book of the Dead), as attested by actual Egyptologists. One reviewer commented, “Hollywood has had a problem with how Egypt is represented in both film and TV. ‘Moon Knight’ has done a superb job with episode three, showing Egypt as an actual modern civilization as opposed to a barren wasteland of only sand with a yellow tinted filter over it.” He does not seem to have noticed that this might be due to the fact that an actual Egyptian director was chosen.

I suppose this is not terribly surprising, since for years there has been a trend toward Hollywood producers suddenly elevating talented foreign and indie directors into the ranks of makers of big franchise films. Taika Waititi went from What We Do in the Shadows and Boy to Thor: Ragnarok and Chloe Zhao from Nomadland to Eternals. (I list a considerable number of similar leaps from the festival scene to the world of blockbusters in my entry on Waititi’s rise to international fame.) Still, Diab seems a strange choice. Maybe Clash was sufficient demonstration that he could do epic scenes of violence. I suppose I shall have to give Moon Knight a look.

Hit the Road (2021)

For years now we’ve been blogging about Panahi films (click on Directors: Panahi in the Categories at the right). Now we have another, but it’s not by Jafar. Panah Panahi is his son, and this is his feature debut. Panah began by making shorts, worked as a set photographer, and later as an editor, most notably on his father’s latest feature, Three Faces.

Hit the Road (the Farsi title is more literally translated as “Dirt Road”) reminded me more of the films of Abbas Kiarostami than of the elder Panahi. Jafar worked as an assistant director on Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (1994). Panah was only ten years old at that point, having been born in 1984, the year of Kiarostami’s early feature documentary, First Graders. The New Iranian Cinema came to world prominence later in the 1980s and into the 1990s. Jafar moved into directing features in 1995 with The White Balloon.

Growing up, Panah must have become familiar with the now-classic films of Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf, as well as those of his father in the years before the latter’s arrest in 2010.

Hit the Road is reminiscent of the “child quest” films of the early years of the movement. In this case, though, the child in question is not the center of the plot, even though the rambunctious kid steals every scene he’s in. He’s accompanying his parents and older son on a road trip that occupies the entire length of the film. The older son is as quiet as his brother is noisy, but it gradually comes out that he is heading for a spot where he will join others being smuggled out of the country in search of better lives. The parents keep this a secret from the little boy, fearing that he will blurt out something that will draw attention to their goal.

The film is a skillful blend of suspense on that account, of a poignant if quarrelsome love among the family, and a good deal of comedy supplied by the little boy. Amid all the raucous exchanges there are quiet moments, as when during a rest stop the unnamed mother nags her older son about smoking too much while sharing a cigarette with him and asking what his favorite movie is. By this point we suspect that she fears that she will never see him again once they reach the border. (Richard Brody’s insightful review captures this mixture of tones.)

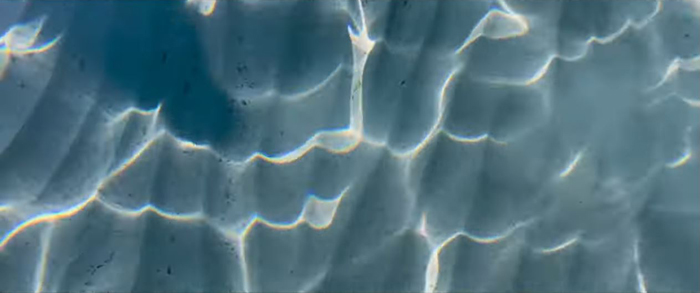

Unlike Amira, Hit the Road is shot entirely out of doors, and often in beautiful, bleak Iranian landscapes (top of entry and below).

At times the family’s SUV climbs hills in shots that recall those of Kiarostami’s films,especially And Life Goes On and The Taste of Cherries, as in the frame at the top of this section. (The literal translation of the Farsi title, Jaddah Khaki, is “Dirt Road.”)

The film has been critically acclaimed and successful on the festival circuit, winner Best Film at the London and Mar del Plata festivals. It seems likely that we will now have two Panahis to report on from future festivals.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire, 2022)

I found Denis’s latest a frustrating and puzzling film for almost its entire length. It reminded me of a similar experience I had with Pablo Larraín’s Ema at the 2019 Venice International Film Festival. I described my initial reaction to that film at the time: “While watching it, I could not discern much of a plot or even a coherent character study.”

Denis’s film, shown outside France under the rather baffling title Fire, starts out innocently enough with a scene of lovers, played by Juliette Binoche and Vincent Lindon, enjoying a blissful, solitary, wordless swim in the ocean. This sets up the “amour” part of the original title. Surprisingly enough, this idyllic sequence, the most visually attractive of the film (above and at the bottom of the entry) was shot during the pandemic on a phone with just the two actors, the director, and the cinematographer present.

Sara and Jean are long-time lovers, and their happiness together continues as they return to their Parisian flat. Soon, however, Sara’s previous lover, François, re-enters their life. He has asked Jean, who has in the past been in prison for some unspecified crime, probably financial, to join him in a athletic scouting agency. Coincidentally, Sara has spotted François in the street, an encounter that seemingly stirs up her old passion for him. She mentions the encounter to Jean, but treats it as a minor thing, expressing pleasure that Jean has been given an opportunity to go into business with his old friend.

From that point the film becomes largely a series of increasingly fraught arguments, as Sara seems to pledge her devotion to both men while resenting the jealousy that they both increasingly feel. All three are revealed to be unpleasant characters acting unwisely, and I, at least, wondered what the point of it all was. The plot seemed to be the classic love triangle, with the question being which man Sara should end up with and whether she will make the right decision–and the issue seeming not to make a great deal of difference for the viewer.

I don’t want to say any more about the plot, since the point of it is to figure out at the very end what Denis had been up to all along. I realized that she was undercutting our expecations about the very clichés that she had presented to us. Apparently I was right. In an interview with Denis, Joseph Cronk mentions that “In an interview in the press notes for the film, you mentioned that the film’s simplicity was ‘a way of foiling clichés.'” Indeed. I’m not sure that many people in the audience with whom I saw the film got the point. I heard some grumbling among the spectators as we left the theater.

It is rather odd to make a film where the audience can “enjoy” it only in retrospect.

I should add that the title Fire does not help a bit.I don’t know who came up with it, but it’s misleading. As Denis has pointed out in interviews, there is no equivalent word to acharnement in English. In the interview mentioned above, Cronk suggests that “With Love and Fury” might be a better title. Denis responds:

No, archarnement doesn’t mean fury. There’s no direct translation, but it means something–from our body, something from your flesh. A sort of tension in the flesh. Fury is something different than acharnement. When I tried translating Avec amour et acharnement, I found no English word I liked that could convey what acharnement means. But Stuart [Staples, the composer] had written the song “Both Sides of the Blade,” and I thought this would be the perfect English title.”

Actually I don’t think “Both Sides of the Blade” would give the spectator much of a clue as to what’s going on in the film. Keeping in mind Denis’s explanation of the French title, however, would.

The quotations from Joseph Cronk’s interview appear in the latest issue of cinema scope, #90 (July 31, 2022), “Not on the Lips: Claire Denis on Avec amour et acharnement.”

Thanks as always to Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, and all the staff and volunteers of the Wisconsin Film Festival.

Avec amour et acharnement (aka Fire).

Wisconsin Film Festival 2021 visits the Middle East

Sun Children (2020)

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival, online this year, continues through this coming Thursday. Films for which audience members buy tickets are all available to watch until 11:59 that night. So far our experiences have been that the streaming system works quite smoothly, with easy access to your chosen titles. Despite geo-blocking (dictated by distributors) in some cases, many films can be watched from outside Wisconsin and the Midwest.

Now, let’s visit the Middle East.

Iran: Sun Children and There Is No Evil

Despite the tragic death of Abbas Kiarostami and the exile into relative obscurity of the Makhmalbaf family, the Iranian cinema continues to produce important films by a small number of auteurs, most prominently Oscar-winner Asghar Farhadi (whose A Hero was recently acquired by Amazon for release later this year), Majid Majidi, the irrepressible Jafar Panahi, and his equally irrepressible colleague Mohammad Rasoulof.

The latter’s There Is No Evil (2020), which won last year’s Golden Bear as best film at the Berlin Film Festival, is on the current WFF program. I wrote about it last year from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Also on the program is Majidi’s latest, Sun Children, which we saw for the first time. Those who think of Iranian festival-oriented films as developing slowly and subtly will be surprised by this one. It is jam-packed with a multi-strand dramatic plot, suspense, fast cutting, and many characters, all handled very skillfully by Majidi.

The film begins with a dedication to the “the 152 million children forced into child labor and those who fight for their rights.” That child labor, as the exciting opening scene emphasizes, often involves small crimes. Four boys set out to steal a tire from a car in the parking garage of a luxurious, multi-storied shopping mall. The suspense begins right away as a guard confronts them. Two of them flee in a classic chase scene, going up through the levels of the mall, past high-end shops that they could never dream of entering. They escape, and it is revealed that the four friends work at a large repair shop, full of stacks of tires, presumably acquired in the same fashion.

Soon Ali emerges as our point-of-view character, desperate to rescue his mother from a mental-health facility. There she lies strapped to a bed after a presumed suicide attempt. Eventually it emerges that the family home recently burned, killing Ali’s sister, whose death drove his mother mad. His father is an addict, and Ali has become the breadwinner. A small-time crime boss sets him a task: enroll in a local school and explore the basement and tunnels under it (above), where a treasure is hidden.

Much of the rest of the film generates more suspense, as Ali diligently makes his way around various obstacles and crawls through branching tunnels day after day, always risking expulsion from the school if he is discovered. His three friends help him at first, but eventually he is left to traverse the seemingly endless tunnels (which are in fact the city’s storm drains).

This part of the film introduces another major plotline, since the school, dependent on private donations, is located in the slums of Tehran. Its aim is to teach young, desperate, potentially criminal boys skills that they can use to get honest jobs. The school is far behind on its rent and in danger of being closed. This adds further suspense as the school officials, particularly a sympathetic vice principal, struggle to find donors. The schools debts lead to one of the film’s big action scenes, as, finding the gates locked one morning, the principal urges the boys to scale the fence. They do this with a determination that reveals their realization that their only hope for a decent life lies in the education they have been receiving.

They eagerly participate in a festival and pageant put on for potential donors (top).

In an interview, Majidi said that the “Sun School” that gives the film its name is based on an actual school in the Tehran slums, the “Sobhe Rooyesh” (“Morning of Growth”). The non-professional child actors, whose performances are all completely natural and affecting, were recruited from the school and surrounding slums. Roolholloh Zammi, who plays Ali, won the Marcello Mastrioanni Award at Venice last year. (I wish we could have been there to see him win!) Only the adults are played by [professional actors.

Israel: Here We Are (2020)

Given the current situation in Israel, it is just as well that Nir Bergman’s gentle psychological study Here We Are (a sadly unmemorable title) has no reference at all to politics, the military, or ethnic tensions. It’s a simple story of a man who has given up his career to care for his severely autistic son and is having difficulties facing the fact that the boy is nearly a man.

The early scenes set up Uri’s disabilities, as well as his obsessions (including pet goldfish–above–and dogs) and phobias (snails). They also establish Aharon’s utter devotion and patience as he cooks yet again Uri’s favorite pasta stars and uses an obviously well-established imitation game to coax his son past imagined snails on a biking route.

The plot action kicks in when Ahron’s estranged wife Tamara shows up, determined to arrange Uri’s transfer to a group home for young people with disabilities. Ahron angrily resists, claiming that Uri is happy at home and that he can care for his son himself.

We seem to be set up to view Ahron as the noble, self-sacrificing father and his wife as the shrewish woman who wants to dictate her son’s life. Eventually, however, Tamara obtains the legal papers requiring Ahron to bring Uri to his new home. Ahron sets out, but along the way he decides to go on the run with Uri, despite having little money.

Along the way there are growing hints that Ahron is stifling both Uri and himself. Twice he simply ignores Uri’s budding sexuality during encounters with young women.

The two seek shelter with an old friend of Ahron’s, Effi, an art teacher who reveals that Ahron had had a prominent and lucrative career as an artist and designer, which he had given up to care for Uri. Her attitude toward Ahron suggests her openness to a romantic relationship with him. Eventually we begin to doubt that he is acting in the best interests of himself and Uri, especially during a scene in which they are forced to dine on ice-cream sandwiches in a bus-station waiting-room.

Here We Are is a film that unfolds gradually and overturns your expectations slowly but thoroughly.

France-Lebanon: Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Chloe Mazlo is a French animator and artist who has previously made shorts (including The Little Stones, which won the 2015 César for Best Animated Short). Inspired by her grandparents’ life in Lebanon (he was Lebanese, she Swedish) during the lengthy civil war, she has made a feature that combines occasional animation with live action.

The film starts out in a stylized, fantastical world that inevitably has led critics to compare Skies of Lebanon to Amélie (2001). Alice, the heroine, is alienated from her parents and her home country, Switzerland, and take a job as a nanny in Beirut. The city as it was in the 1950s is represented by matte shots of actors presumably filmed against a green-screen, with backgrounds filled in by blow-ups of tinted postcards of the period. Such shots have a charming effect.

Alice meets cute with a handsome physicist whose goal is to invent a rocket to put the first Lebanese astronaut into space. Their romance develops in a fantasy landscape of patently artificial rocks and stars (bottom). They settle down together, raise children, and pursue their careers, with Alice becoming a watercolorist.

The fantasy strain in the film is most obvious in the brief animated scenes, as when a split-screen telephone conversation juxtaposes the real Alice with puppets representing her angry parents, who demand that she return home (top of section).

About a third of the way into the film, the tone switches abruptly as the Lebanese civil war breaks out. The animations and postcard background disappear. As characters flee and disappear mysteriously, a shot of a wall with “have you seen” photos pasted up emphasizes the danger that Alice is trying to ignore.

Even during the lengthy wartime portion of the film, there remains a faint underlying humor. Yet the abrupt shift of tone when the war starts is unsettling, given that we had settled down for a whimsical romance and end up with a war story. Presumably the idea is to emphasize how war breaks into the calm of ordinary life and banishes it. Whether audiences will take it that way is another matter. On the whole, however, the film is an imaginative and promising first feature.

The Festival’s Film Guide page links you to free trailers, podcasts, and Q &A sessions for each film.

Thanks as ever to the untiring efforts of Kelley Conway, Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Pauline Lampert, and all their many colleagues, plus the University and the donors and sponsors that make this event possible.

Skies of Lebanon (2020)

Vancouver 2019: Some final observations

It Must Be Heaven (2019).

We wrap up our coverage of this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival with a joint entry on movies from around the world.

Kristin here:

Out of Tune (2019)

Danish director Frederikke Aspöck has created a prison film with a seamless combination of humor, social commentary, and a subtly disturbing undertone.

Markus Føns arrives in jail, awaiting trial for corporate fraud. As a result of his popular financial advice books, he is notorious for having caused many to face financial ruin. He runs into the thuggish brother of a man who has lost a huge amount through Markus’ advice. The brother insists that Markus is owes the brother the full amount he lost. He dismisses Markus’ point that all investments are a gamble and, along with his gang, beat Markus up.

Terrified of further violence, Markus voluntarily transfers to the solitary-confinement wing, joining rapists, child molesters, and others who fear being attacked by other inmates. The prisoners in this wing are not really isolated, however. They’re let out to do chores, to sing in a choir, and to earn a bit of money by making pom-poms for local schools and celebrations.

The choir members (above), led by Niels, prove an engaging bunch, and much humor is generated by their disagreements about which songs from a collection of Danish classics they should sing. Markus initially sticks to his cell but finally joins the group. In one of the film’s funniest scenes, Niels insists that Markus is not a tenor but a bass, forcing him to sing in a range that clearly is not natural to him.

One of the rules of solitary is that the prisoners are not allowed to reveal or discuss their crimes–though Markus is famous enough that all the others know what he did. Simon, a genial young black man, admires Markus and increasingly becomes his ally against the dictatorial Niels.

Gradually the tone darkens, however, as it is revealed that two of the main characters, including Niels, are pedophiles. Markus declares that his white-collar crimes are less heinous than child molestation. The others, however, including Simon, declare Markus’ crimes worse. At that point he decides to take his revenge on the group and especially Niels, by seizing the leadership of the choir.

This balancing act between humor and drama works well, with Aspöck managing to make the pedophiles somewhat sympathetic and amusing characters without excusing their crimes. The satire on how upper-class celebrity criminals like Markus manage to become objects of fascination is effective without becoming heavy-handed.

It Must Be Heaven (2019)

I am a fan of the Palestinian director Elia Suleiman, who manages to make autobiographical feature films at wide intervals. I am particularly fond of Divine Intervention (2002) and I also like The Time That Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee, which we saw in Vancouver in 2009.

It Must Be Heaven does not quite achieve the excellence of those earlier two films, being a bit uneven. Still, it contains many excellent scenes and gags, and it was among the best films I saw at this year’s festival.

The earlier portion sets up Suleiman’s sense of unease about the events that surround him in his native Nazareth. A running motif has him peeping timidly over his back wall as his neighbor’s son without permission picks lemons from his trees. Gradually the man takes over the care of the whole orchard.

Eventually Suleiman goes abroad, and we soon learn that he is seeking funding for his next film, presumably the film we are now watching.

Two of the funniest scenes take place in the offices of the producers Suleiman visits in Paris and New York. Both end in failure, but the huge number of international companies and funding agencies listed in the credits suggests that the director’s efforts must have been complex, lengthy, and, in some cases successful. The scene in New York involves a cameo by Gael García Bernal, who has an offer on a Mexican project of his own, but he obviously has little control of that project, let alone the ability to aid his friend Suleilman. The one in Paris has Vincent Maraval, of Wild Bunch (one backer of the film) playing a producer who rejects the project as not Palestinian enough.

Other than visiting producers, Suleiman wanders the streets of Paris and New York, observing incongruous events around him. Some of these are very amusing, others simply odd.

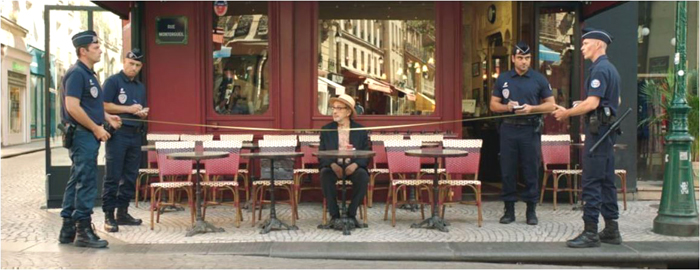

Comparing It Must Be Heaven to Suleiman’s earlier “autobiographical” films, the basic problem here becomes apparent. While Suleiman (or an actor playing him as a child) wove in and out of the action, participating in it, here many scenes involve him as a largely passive observer of events that have little or nothing to do with him. In one such scene, he sits at a cafe table, watching as four police officers carefully measure the spaces of the outdoor tables before pronouncing them compliant with regulations (see top). In Palestine he walks in the country and observes a Bedouin woman with a novel way of transporting two large vats of liquid. In Paris he observes police on Segways performing a search in the street below in perfectly choreographed loops. At times he is more affected by the action, as when a tattooed muscle-man stares at him threateningly in an otherwise empty Métro car.

Suleiman is an engaging performer, but watching him stare in bemusement at the odd behavior that he encounters in each place he visits grows a bit old. Nevertheless, there are many funny or just bizarre scenes in the film, including a lengthy tussle between Suleiman and an invading sparrow determined to perch on his keyboard. The visit to Paris, in which Suleiman somehow got the streets emptied so that he wanders completely alone through them is both impressive and somewhat disconcerting (above).

Suleiman is routinely compared to Tati and Keaton, but his work is similar to that of Roy Andersson too, is equally apt, although Andersson does not assign a single character to be an observer. Here to a considerable extent Suleiman keeps to the long-shot framings that are familiar from his other films, but there are also more close-ups, in particular of his face as his reacts to what he sees.

It Must Be Heaven suggests that wherever Suleiman goes once he leaves his Palestinian home, he sees the same sorts of odd behavior, especially the violence that has become endemic everywhere. (A particularly hilarious episode shows Suleiman shopping in New York and noticing that everyone around him, including babies, is carrying some sort of weapon, from pistol to bazooka.) I suspect, however, that most viewers would fail to catch the political points Suleiman claims in interviews to be making.

DB here:

Oh Mercy (Roubaix, une lumière)(2019)

Arnaud Desplechin regards his previous films (Esther Kahn, Kings and Queen, A Christmas Tale) as “a fireworks of fiction,” as he explained in a Q & A session. His latest, Oh Mercy, is based on fact. The screenplay dramatizes criminal cases that took place in Roubaix, the impoverished town Desplechin grew up in. The result is an unusual policier, which twists some crime-movie conventions in intriguing ways.

As we expect, the cops form a team. The emphasis is divided between the young and eager Louis Coterelle and the experienced chief Daoud. But Coterelle is an ascetic young man, reminiscent of Bresson’s country priest. Daoud, rather than being the tough boss who has to make his staff shape up, is an eerily quiet and sympathetic professional. Cast out by his family, he devotes his life to his work (and the occasional horse race). These characters keep surprising us. It’s the pious Coterelle who, pushing to make his mark, bullies suspects, while Daoud’s gentle ways eventually tease the truth out of them.

The police procedural typically shows several cases worked at once, with some minor ones and others explored in more detail. Desplechin’s film does the same, as an automobile fire and a petty robbery introduce us to the main cops. To help a friend, Daoud must also investigate a runaway teenager. Soon there’s a building fire, and then a murder on the same block. Gradually it becomes clear that these two crimes are connected–another convention of the genre.

It’s the nature of the connection, though, that reveals Desplechin’s originality. About halfway through the film the police commit their energies to questioning two women, Claude and Marie, who share an apartment. In a string of riveting interrogations, the film shows Coterelle and Daoud, each in their own way, peeling back layers of the women’s relationship. It’s a tour de force relying on the Prisoner’s Dilemma, and it reveals as much about the cops as it does about the sad, confused lovers. Even the reenactment of the crime, another staple of the genre, avoids sensationalism and achieves a mournful gravity.

Most cop movies make justice a matter of vengeance (“This time it’s personal”), so it’s rare to find one about pity. The lies and mistaken memories that prolong the investigation are accepted by Daoud with quiet compassion. A gradual-revelation film like this, impeccably plotted and directed though it is, depends crucially on performances, and the principals (Roschdy Zem as the patient Daoud, Léa Seydoux as Claude, Antoine Reinartz as Coterelle) are extraordinary. Above all I will remember Sara Forestier as the skittish Marie, perpetually corrugating her forehead, always a beat behind in appraising how much the woman she loves loves her.

Once more we thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies. In addition, we appreciate the generosity of Arnaud Desplechin in answering questions about his film.

Oh Mercy (2019).

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

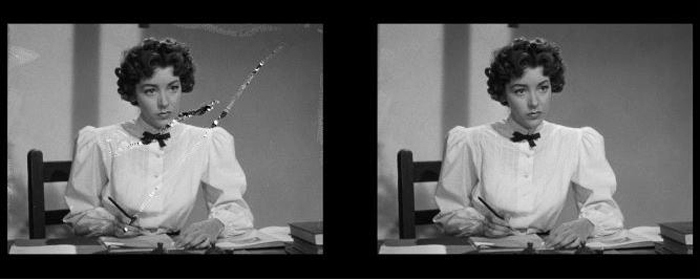

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).