Archive for the 'National cinemas: Middle East' Category

Vancouver 2018: A final few films

Kristin here:

As I write, David and I have been at home after the Vancouver International Film Festival for one week. Between Venice and Vancouver, I saw about 40 films, some of them likely awards competitors for the year and some more modest works that need to be sought out at festivals and big-city art-houses. (Today, in a cyclical gesture, we’re going back to the very first film we saw at Venice, First Man, this time in IMAX.)

During any festival there’s never time enough to write up comments on all the films we see. This is our last report on the 2018 Vancouver event, this time dealing with Middle Eastern films and one from South America.

3 Faces (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

3 Faces begins startlingly, with a vertical cell-phone image of a girl in a rocky area, dictating a suicide note as she walks. She identifies herself as Marziyah, a peasant girl who aspires to be study acting but whose conservative family (along with their entire village) have blocked her from doing so. She has written repeatedly to a famous TV actress, Behnaz Jafari (played by herself) for help, but receiving no response, she has decided to kill herself. The recording ends as the girl apparently hangs herself and the camera falls.

The image opens to fullscreen as Jafari, riding in a car with Panahi, watches the recording, distraught at the possibility that she has failed to help the girl. She also wonders whether Marziyah has really killed herself. Was the film edited to create that impression? Panahi thinks it looks authentic, and he drives Jafari out to the girl’s village to find out.

3 Faces is the fourth feature Panahi has made since his trial in 2010 and the resulting sentence banning him from filmmaking for twenty years. We had been following his career before that, most notably with The Circle and Offside. In happier days, David met Panahi briefly at the Hong Kong Film Festival, when they sat next to each other at an award ceremony. David posted an account of Panahi’s charges and sentencing in 2010. We have also written about films that Panahi has made since then: This Is Not a Film and Closed Curtain. Somehow, though we saw Taxi, we didn’t blog about it. Today Panahi remains unable to leave Iran to attend the festivals where his films are honored (3 Faces won the best-screenplay award at Cannes), and he has no access to studio facilities.

With 3 Faces, Panahi has moved on from making films about his plight and looks at the repression suffered by women and girls in the rural areas of Iran.

This time he follows the classic quest pattern of many of the golden age of Iranian cinema from the 1980s to the early 2000s. 3 Faces is perhaps most reminiscent of Kiarastami’s And Life Goes On, another director’s journey to the countryside to check on a child who may have died. It’s gratifying to see the fruitful quest pattern revived, and Panahi creates a work that is at once familiar and uniquely imaginative. The settings, mostly in Panahi’s car and the countryside of Iran near the Turkish border.

As in other such films, 3 Faces is as much about the unexpected encounters with strangers along the way: a wedding group celebrating on a steep mountain road, a woman testing out her own grave to make sure it’s comfortable, an old man who introduces Panahi to the patterns of honks locals use when approaching each other on the narrow roads. Upon reaching the village and encountering Marziyah’s family, it becomes apparent that they are baffled and annoyed by the girl’s ambitions to devote herself to a frivolous career rather than marry and settle down.

Jahari also encounters a retired actress from before the 1979 revolution, Shahrazade, now a recluse living in a tiny house near the village (see top). The “3 Faces” title apparently refers to the three generations of actresses, Shahrazade, Jafari, and Marziyah. This explanation is not apparent from the film, especially since Shahrazade is glimpsed only in extreme long shot from the back as she paints in a field.

Panahi has made a more acerbic film than those of Kiarostami, poking fun at the villages and especially emphasizing the way the men are obsessed with virility and controlling their womenfolk. Receding into the background despite his major role, Panahi takes p the feminism he displayed in Offside and reveals the more serious lack of freedom women and girls experience in rural areas. He does so without abandoning the humor that underlies many of the quest films.

Kino Lorber will distribute the film in the US, with a release planned for March, 2019.

Dressage (Pooya Badkoobeh, 2018)

Another trend in recent Iranian cinema might be termed the Farhadi effect. Asghar Farhadi has become the most prominent of the current group of Iranian directors, winning best foreign-language Oscars for both A Separation and The Salesman. His films tend to center around a serious mistake or a crime committed early on, with the varying reactions of the characters forming the bulk of the drama. In some cases sudden twists reveal motivations that tend to make the situation more ambiguous morally, and the rights and wrongs of the situation do not resolve clearly.

Dressage, Badkoobeh’s first feature, fits this pattern to some degree. A group of middle-class and upper-middle-class students are in the habit of robbing shops for thrills. As the film opens, they have robbed a small grocery store. When a clerk who lives in the store unexpectedly interrupts them, their leader knocks him out. Having fled, the group discovers that they have neglected to take the incriminating surveillance tape with them. The protagonist, sixteen-year-old Golsa, is sent back for it. Having retrieved it, she hides it in a bin at the stables where she helps take care of expensive dressage horses (above).

Golsa refuses to turn over the tape, either to the group or to her parents, all of whom wish to destroy the evidence. What Golsa plans to do with the tape is unclear, but she is subjected to more and more pressure to give it up. Along the way, her stubbornness begins to harm the very working-class people, such as the store clerk, whom she hopes to help.

The rather simple story is given some depth by Golsa’s love for one of the dressage horses. It’s made clear that such horses are valuable and must be exercised without letting them run free, which would risk damage to their legs, but at one point she takes her favorite into a field to frolic about.

Ultimately the film has less of the complexity and ambiguity of a Farhadi film, but it shows promise for a younger generation of Iranian filmmakers.

As far as I can determine, Dressage does not have a North American distributor.

Caphernaüm, aka Capernaum (Nadine Labaki, 2018)

I remember that during the Cannes festival, Kore-eda’s Shoplifters and Labaki’s Capernaum were among the films most often predicted to win the Palme d’Or. In the event, Shoplifters took the top prize, and justifiably so, and Capernaum received the Jury Prize, the second highest honor. Both films center around families living in poverty, though Shoplifters moves among the members of its family and emphasizes their mutual support. Capernaum, on the other hand stays resolutely with Zain, the 12-year-old boy who is so miserable that he takes his parents to court to sue them for having brought him into a wretched existence in the Beirut slums.

Labaki, determined to expose the reasons for the sufferings of children in the poorer areas of Beirut, spent three years researching the subject. She cast actual slum-raised children rather than actors and coaxed remarkable performances from them. It seems absurd to speak of a performance from the one-year-old girl who plays Yonas, the little boy whom Zain struggles to care for when the toddler’s Ethiopian-emigré mother is arrested for lack of proper papers; still, the child seems always to be doing exactly what is natural and appropriate for the situation. The result of working with non-professionals and children was 500 hours of footage to be edited down into a two-hour film. (The production information is from an interview with Labaki in The Hollywood Reporter.)

It seems churlish to find fault with Capernaum, which certainly must be given credit for exposing a side of life that most viewers will never witness. It mixes humor and pathos with a deft hand and is undoubtedly entertaining and thought-provoking. Yet there are moments when the film’s effort to tug at our heartstrings seems a bit too obvious and overdone. Some critics have been unqualifiedly moved by the film, while others find it a bit too manipulative. I suspect that most audiences who see it in art-houses in the US will share the reaction of the Cannes audience, who gave it a 15-minute standing ovation.

The meaning of the film’s title is intriguing, and some clarification might be helpful. I have given both its original Lebanese title, Capharnaüm, and the one used in English-speaking countries, Capernaum. They are variant spellings of the same word, but with different meanings. “Capharnaüm” is French and means “a confused jumble” or “a place marked by a disorderly accumulation of objects” (Merriam-Webster). It derives from the Aramaic spelling of the Hebrew name Capernaum, the village on the Sea of Galilee where Jesus is said in the Bible to have been based during most of his ministry.

The “confused jumble” derives from the large crowds that flocked around Jesus, as in Mark: 1-2:

And again he entered into Capernaum after some days, and it was noised that he was in the house.

And straightaway many were gathered together, insomuch that there was no room to receive them, no, not so much as about the door; and he preached the word unto them.

Labaki, being a Catholic (belonging to the Lebanese Maronite Church and having been educated at St. Joseph University in Beirut), would surely have been aware of both these meanings when she made her film. The notion of a crowded jumble applies well to the environments in which the children in the film live. Certainly the children belong to the downtrodden classes to whom Jesus ministered. Possibly the reference to Jesus’ miracles, several of were reportedly performed in Capernaum, helps to justify the implausibly upbeat ending of the film.

Capernaum will be released in the US by Sony Pictures Classics on December 14.

Birds of Passage (Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018)

Birds of Passage is the first film directed by Ciro Guerra since his excellent Embrace of the Serpent, which was the first Colombian film nominated for a foreign-language Oscar. This time he co-directs with his wife and producer, Cristina Gallego.

Birds of Passage is a very different film from Embrace of the Serpent. The latter is set in the Colombian Amazon region, focuses on the decimation of indigenous peoples by the rubber trade, is shot in black and white, and cuts between two time periods decades apart involving two explorers guided by the same indigenous guide. Birds of Passages is set in a desert region of northern Colombia, deals with the early effects of drug-trafficking among the Wayuu people of the area, is shot in color, and follows a single extended family chronologically through five periods between the 1960s and 1980s, each announced by a dated title.

The result is a plot that is much easier to follow than that of Embrace of the Serpent. While the earlier film was based around the evocative, mysterious hunt through the jungle for a fictional sacred plant, Birds of Passage is very much anchored in the history of the early marijuana trade that the central family becomes involved in, growing very rich in the process.

In the film, the first American customers who draw the ambitious hero, Raphayet, to obtain a small amount of marijuana for them are some Peace Corps volunteers. Soon criminal traffickers become customers for Raphayet’s wares, and the roughly two decades of drug-running that follow balloon into a business that ends with a war within the family (see bottom).

The title refers to a motif that is introduced in the opening scene, when teenage Zaida, of the foremost family among the Wayuu, finishes her official transition to womanhood with a ritual dance based on bird mating rituals. Raphayet offers to dance with her (above), and the task of meeting her mother’s high dowry price includes him making his first small drug deal. The motif of real birds continues, but migrating “birds of passage” is also a local term for the American traffickers who fly in and out in small planes, bringing money in such large bundles that have to be weighed rather than counted.

As a film, Birds of Passage is not as challenging or evocative as Embrace of the Serpent. Its fascinating story, however, deals with the little-known history of the origins of the South American drug trade, the growing problem that has caused such upheaval in the region and is very much still with us.

The Orchard has the US rights, with no announced release date.

Returning for a moment to the Venice International Film Festival, three publications generated by the 2018 festival are now available for sale.

Two of these publications result from the festival’s 75th anniversary this year. Peter Cowie’s Happy 75º: A Brief Introduction to the History of the International Film Festival offers a succinct, chronological account of the festival’s facilities, organizers, guests, and winners year by year. Reading it enlivened the time spent in line before films for both David and me.

The festival also presented a large exhibition of photographs, again presented year by year, celebrating the films shown and the stars attending. This exhibition was mounted in the legendary Hotel des Bains, closed in recent years but formerly housing many of the festival’s glamorous guests. It is mainly connected in the minds of most moviegoers with Visconti’s Death in Venice, which was filmed there. There are plans to renovate and re-open it. A large catalog containing what appear to be all the photographs from the exhibition has also been published.

Finally, this year’s program, with extensive notes on the films, is available.

All of these can be ordered from amazon.it. The program can also be downloaded.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help during our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Birds of Passage

Unveiling Ebertfest 2014

Kristin here:

In the early days of Ebertfest, Roger personally introduced every film at this five-day event, which took place this year from April 23 to 27. He would be onstage for the discussions and question sessions after each screening, often joined by directors, actors, or friends in the industry.

In the summer of 2006, there began the long battle with cancer that Roger fought so determinedly. He withdrew gradually from full participation in the festival that he had founded in his hometown of Champaign-Urbana sixteen years ago. He struggled to immerse himself in the festival, even though repeated surgeries had robbed him of his voice. He introduced fewer films, doing so with his computer’s artificial voice, and when even that became too taxing, he sat in his lounge chair at the back of the Virginia Theater, enjoying the event and occasionally appearing onstage with a cheery thumbs-up. Finally, last year on April 4, less than three weeks before the fifteenth Ebertfest, he passed away. That year’s festival became a celebration of his life.

The celebration continued this year, though on a more upbeat note. Some films were chosen from a list that Roger had left to his wife Chaz and festival organizer Nate Kohn, and they selected others in the same indie spirit. The tradition of showing a silent film with musical accompaniment was maintained. As always, the festival passes sold out, and the crowd, including many long-time regulars, enthusiastically cheered both films and filmmakers.

The tributes

Roger did not live to see the documentary devoted to his life and based on his popular memoir of the same name, Life Itself. It premiered in January at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. He participated in its making, however, encouraging director Steve James (whose 1994 documentary Hoop Dreams Roger had championed) to film him during the final four months of his life. Some of this candid footage reveals the painful and exhausting treatments Roger underwent, but much of it stresses his resilience and the support of Chaz and the rest of his family.

Life Itself was the opening night film. James has done a wonderful job of capturing the spirit of the book and in assembling archival footage and photographs, interspersed with new interviews. The result is anything but maudlin, with a candid treatment of Roger’s early struggles with alcoholism and an amusing summary of Roger’s prickly but affectionate relationship with his TV partner Gene Siskel.

Life Itself was picked up for theatrical distribution by Magnolia Pictures and will receive a summer release, followed by a showing on CNN. (Scott Foundas reviewed the film favorably for Variety, as did Todd McCarthy for The Hollywood Reporter.)

Another tribute followed the next day, when a life-size bronze statue of Roger by sculptor Rick Harney was unveiled outside the Virginia Theater (above). Harney portrays Roger in his most famous pose, sitting in a movie-theater seat and giving a thumbs-up gesture. There is an empty seat on either side of him, so that people can sit beside the statue and have their photos taken. (See the image of Barry C. Allen in the section “Of Paramount importance,” below.)

Far from silent

Roger was a big fan of the Alloy Orchestra, consisting of (L to R above) Terry Donahue, Ken Winokur, and Roger Miller, who specialize in accompanying silent films. They have appeared several times at Ebertfest, playing original music for such films as Metropolis and Underworld. Rather than taking a traditional approach to silent-film music, using piano, organ, or small chamber ensemble, they compose modern scores, played on electronic keyboard combined with their well-known “rack of junk” percussion section, including a variety of found objects, supplemented with musical saw, banjo, accordion, clarinet, and other instruments. The result is surprisingly unified and provides a rousingly appropriate accompaniment to the silents shown at Ebertfest over the years.

I have had the privilege of introducing the film and leading the post-film Q&A on some of these occasions, including for this year’s feature, Victor Seastrom’s 1924 classic, He Who Gets Slapped. (Swedish director Victor Sjöström used the Americanized version during his career in Hollywood.) I put the film in context by pointing out three important historical aspects of the film. First, it was the first film made from script to screen by the newly formed MGM studio, formed in 1924 from the merger of Goldwyn Productions, Metro, and Louis B. Mayer Pictures. (Two earlier releases by MGM were Norma Shearer vehicles which originated at Mayer.) Second, it was probably the film that cemented Lon Chaney’s stardom, after his breakthrough role as Quasimodo in the 1922 Hunchback of Notre Dame. Starting in 1912, Chaney had been in well over 100 films before Hunchback, many of them shorts and nearly all of them supporting roles. Third, He Who Gets Slapped was Seastrom’s second American film after Name the Man in 1923, and a distinct improvement on that first effort.

Naturally MGM wanted a big, prestigious hit for its first production, and He Who Gets Slapped came through, being both a critical and popular success–and also boosted Norma Shearer to major stardom. Seastrom and Chaney both stayed on at MGM, though the former returned to European filmmaking after the coming of sound and Chaney died in 1930.

I was joined for the post-film discussion by Michael Phillips of the Chicago Tribune, and we talked with Donahue and Winokur while Miller sold the group’s CDs and DVDs in the festival shop. They revealed that this new score had been commissioned by the Telluride Film Festival and that it was a project that appealed to their taste for off-beat films. There were many questions from the audience, and we suspect that the Alloy Orchestra will continue to be a regular feature of the festival.

A cornerstone of indie cinema

Although Roger was occasionally criticized for supposedly lowering the tone of film reviewing by participating in a television series, he and partner Gene Siskel regularly tried to promote indie and foreign films that didn’t get wide attention. Roger did the same in his written reviews, and Ebertfest was originally known as the “Overlooked Film Festival.” Inevitably it was shortened by many attendees to “Ebertfest,” and eventually that name became official. It reflects the wider range of films that came to be included, with the silent-film screening and frequent showings of 70mm prints of films like My Fair Lady that were hardly overlooked.

Among Roger’s friends was Michael Barker, co-founder and co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, one of the most important of the small number of American companies still specializing in independent and foreign releases. A long-time Ebertfest regular, Barker usually brings a current or recent release to show, along with filmmakers or actors. This year he was doubly generous, bringing Capote (2005, above), to which Roger had given a four-star review, and the current release Wadjda (2012).

Roger never reviewed the latter, but it is certainly the sort of film that he loved: a glimpse into a little-known culture by a first-time filmmaker with a progressive viewpoint. Wadjda is remarkable as the first feature film made in Saudi Arabia, where there are no movie theaters. Moreover, it was made by a woman, Haifaa Al-Monsour, and tells the story of a little girl who defies tradition by aspiring to buy and ride a bicycle in a country where this, like women driving cars, was illegal. (Below, Wadjda learns to ride a bicycle on a rooftop, hidden from public view.)

Both the film and Al-Monsour thoroughly charmed the audience. Barker interviewed her afterward, and she revealed that, not surprisingly, the making of the film was touched by the same sort of repression that it portrays. Women are not allowed to work alongside men in Saudi Arabia, so Al-Monsour had to hide in a van while shooting on location. Given that there is no cinema infrastructure in the country, the film was a Saudi Arabian-German co-production, with Arabic and German names mingling in the credits. We also learned that it has since become legal for Saudi girls to ride bicycles. Perhaps someday filmmaking will become more common there, and male and female crew members can work openly together.

Naturally Wadjda was made with a digital camera, since this new technology is crucial to the spread of filmmaking in places like the Middle East where there is little money or equipment for production. In contrast, Capote was shown in a beautiful widescreen 35mm print that looked great spread across the entire width of the Virginia’s huge screen. Naturally the screening became a tribute to the late Phillip Seymour Hoffman, giving his only Oscar-winning performance (out of four nominations) in the lead role.

Barker had brought with him a surprise guest, Capote‘s director, Bennett Miller, whose appearance had not been announced in advance. He discussed how he and scriptwriter Dan Futterman learned that there was a second, rival Capote film in the works, Infamous (2006), which also dealt with the period when the author was researching In Cold Blood. Miller and Futterman decided to press ahead, a wise move in that their film drew more attention than did Infamous. Much of the discussion was devoted to Hoffman’s performance and his acting style in general.

Capote was Miller’s first fiction feature. He had come to public attention with his documentary The Cruise (1998), which Roger had given a brief three-star review. Roger continued his support for Miller with a four-star review for Moneyball (2011). It’s a pity he did not live to see Miller’s latest, Foxcatcher, which will be playing in competition at Cannes in May.

Overlooked no longer

Perhaps no young filmmaker better demonstrates the impact that Roger’s support can have on a career than Ramin Bahrani. Roger saw his first feature, Man Push Cart, at Sundance in 2006 and invited it and the filmmaker to the  “Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

“Overlooked Film Festival” that April. (Roger’s Sundance review is here.) The film then played other festivals, notably Venice and our own Madison-based Wisconsin Film Festival. It won several awards, including an Independent Spirit Award for best first feature. In October Roger gave the film a more formal review, awarding it four stars. Man Push Cart never got a wide release, and it certainly didn’t make much money. Still, quite possibly the high profile provided by Roger’s attention allowed Bahrani to move ahead with his career.

His second film, Chop Shop, brought him to Ebertfest a second time, in 2009. (Roger’s program notes are here, and his four-star review here.) At about that time, Bahrani’s third film, Goodbye Solo, was released. Given its modest budget, it did reasonably well at the box office, grossing nearly a million dollars worldwide (in contrast to Man Push Cart‘s roughly $56 thousand). Bahrani inched toward mainstream filmmaking with At Any Price (2012), starring Dennis Quaid and Zac Efron, and he is currently in post-production on 99 Homes, with Andrew Garfield, Michael Shannon, and Laura Dern. During the onstage discussion, he spoke of struggling to maintain a balance between the indie spirit of his earlier films and the more popularly oriented films he has recently made.

Bahrani visited Ebertfest for a third time this year, belatedly showing Goodbye Solo. We had enjoyed this film when it came out, and it holds up very well on a second viewing. It’s a simple story of opposites coming together by chance. An irrepressibly talkative, friendly immigrant cab driver, Solo (a nickname for Souléymane), becomes concerned when a dour elderly man engages him for a one-way trip to a regional park whose main feature is a windy cliff. He fears that William is planning suicide. Solo arranges to drive William whenever he calls for a cab and even becomes his roommate in a cheap hotel. Gradually, with the help of his young stepdaughter Alex, he seems to draw William out of his defensive shell.

As in Bahrani’s earlier films the main character is an immigrant and played by one, using his own first name (Souléymane Sy Savané). He’s the main character in that we are with him almost constantly, seeing William only as he does. William is a vital counterpart to him, however. He is perfectly embodied by Red West, an actor who worked for Elvis Presley and did stunt work and bit parts in films and television since the late 1950s. He may look vaguely familiar to some viewers, but he’s not really recognizable as a star and comes across convincingly as an aging man buffeted by life’s misfortunes.

Most of the film takes place in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, Bahrani’s hometown, with many moody, atmospheric shots of the cityscape at night. One crucial scene involves a drive into the woods and mountains, however, and much of it is filmed in a dense fog. One questioner from the audience asked if Bahrani had planned to shoot in such weather or if, given his short shooting schedule, the fog turned out to be a hindrance to him. He responded that he had dreamed of being able to shoot in fog and that the weather cooperated on the three days planned for that locale. In fact, he re-shot some images as the fog became denser, to keep the scene fairly consistent.

Bahrani’s presence at Ebertfest spans half its existence, from 2006 to 2014. As the festival becomes more diverse in its offerings, it is good to have him back as a reminder of the Ebertfest’s early emphasis on the “overlooked.”

Of Paramount importance

Logo for National Telefilm Associates, TV syndication arm of Republic Pictures.

DB here:

Among the guests at this year’s E-fest was Barry C. Allen. For over a decade Barry was Executive Director of Film Preservation and Archival Resources for Paramount. That meant that he had to find, protect, and preserve the film and television assets of the company—including not just the Paramount-labeled product but libraries that Paramount acquired. Most notable among the latter was the Republic Pictures collection.

We may think of Republic as primarily a B studio, but it produced several significant films in the 1940s and 1950s—The Red Pony, The Great Flammarion, Macbeth, Moonrise, and Johnny Guitar. John Wayne became the most famous Republic star in films like Dark Command, Angel and the Badman, and Sands of Iwo Jima. John Ford’s The Quiet Man was Wayne’s last for the studio, which folded in 1959. Next time you see one of the gorgeous prints or digital copies of that classic, thank Barry for his deep background work that underlies the ongoing work of his dedicated colleagues.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Barry told me quite a lot about conservation and restoration, but just as fascinating was his account of his earlier career. A lover of opera, literature, and painting since his teenage years, he was as well a passionate movie lover. An Indianapolis native, he thinks he saw his first movie in 1949 at the Vogue, now a nightclub. He projected films in his high school and explored still photography. He was impressed when a teacher told him: “If you want to make film, learn editing.” Soon he was in a local TV station editing syndicated movies.

Hard as it may seem for young people today to believe, in the 1950s TV stations routinely cut the films they showed. Packages of 16mm prints circulated to local stations, and these showings were sponsored by local businesses. Commercials had to be inserted (usually eight per show), and the films had to be fitted to specific lengths.

WISH-TV ran three movies a day, and two of those would be trimmed to 90-minute air slots. That meant reducing the film, regardless of length, to 67-68 minutes. Barry’s job was to look for scenes to omit—usually the opening portions—and smoothly remove them. Fortunately for purists, the late movie, running at 11:30, was usually shown uncut, and then the station would sign off.

By coincidence I recently saw a TV print of Union Depot (Warners, 1932) that had several minutes of the opening exposition lopped off. We who have Turner Classic Movies don’t realize how lucky we are. Fortunately for film collectors, some stations, like Barry’s, retained the trims and put them back into the prints.

While working at WISH-TV, Barry began booking films part-time. He programmed some art cinemas in the Indianapolis area during the early 1970s, mixing classic fare (Marx Brothers), current cult movies (Night of the Living Dead), and arthouse releases like Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie—a bigger hit than anyone had anticipated. He also helped arrange a visit of Gloria Swanson with Queen Kelly; she carried the nitrate reels in her baggage.

At the same time, Barry was learning the new world of video editing, with ¾” tape and telecine. Because of his experience in television, Barry was contacted by Paramount to become Director of Domestic Syndication Operations. His chief duty was to deliver films to TV stations via tape, satellite, and prints. From that position, he moved to the preservation role he held until 2010, when he retired.

Barry is a true film fan. He has reread Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By many times and retains his love for classic cinema. The film that converted him to foreign-language cinema was, as for many of his generation, Children of Paradise, but he retains a fondness for Juliet of the Spirits, The Lady Killers, and other mainstays of the arthouse circuit of his (and my) day. He’s proudest of his work preserving John Wayne’s pre-Stagecoach films.

It was a great pleasure to hang out with Barry at Ebertfest. Talking with him reminded me that The Industry has long housed many sophisticated intellectuals and cinephiles. Not every suit is a crass bureaucrat.

Young-ish adult

Patton Oswalt had planned to come to Ebertfest in an earlier year, to accompany Big Fan and to show Kind Hearts and Coronets to an undergrad audience. He had to withdraw, but he showed up this year. On Wednesday night he screened The Taking of Pelham 123 to an enthusiastic campus crowd, and the following night, after getting his Golden Thumb, he talked about Young Adult. (Roger’s review is here.)

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

As you might expect from someone who has mastered stand-up, writing (the excellent Zombie Spaceship Wasteland), TV acting, and film acting, Oswalt stressed the need for young people to grab every opportunity to work. He enjoys doing stand-up; with no need to adjust to anybody else, it’s “the last fascist post in entertainment.” But he also likes working with other actors in the collaborative milieu of shooting film. He insists on not improvising: “Do all the work before you get on camera.” I was surprised at how quickly Young Adult was shot—one month, no sets. Oswalt explained that one aspect of his character in the film, a guy who customizes peculiar action figures, was based on Sillof, a hobbyist who does the same thing and sells the results. Oswalt talks about Sillof and Roger Ebert here.

It’s common for viewers to notice that Mavis Gary, the malevolent, disturbed main character of Young Adult, doesn’t change or learn. “Anti-arc and anti-growth,” Oswalt called the movie. I found the film intriguing because structurally, it seems to be that rare romantic comedy centered on the antagonist.

Mavis returns to her home town to seduce her old boyfriend, who’s now a happy husband and father. A more conventional plot would be organized around Buddy and his family. In that version we’d share their perspective on the action and we’d see Mavis as a disruptive force menacing their happiness.

What screenwriter Diablo Cody has done, I think, is built the film around what most plots would consider the villain. So it’s not surprising that there’s no change; villains often persist in their wickedness to the point of death. Attaching our viewpoint to the traditional antagonist not only creates new comic possibilities, mostly based on Mavis’s growing desperation and her obliviousness to her social gaffes. The movie comes off as more sour and outrageous than it would if Buddy and Beth had been the center of the plot.

Making us side with the villain also allows Oswalt, as Matt Freehauf, to play a more active role as Mavis’s counselor. In a more traditional film, he’d probably be rewritten to be a friend of Buddy’s. Here he’s the wisecracking voice of sanity, reminding Mavis of her selfishness while still being enough in thrall to high-school values to find her fascinating. As in Shakespearean comedy, though, the spoiler is expelled from the green world that she threatens. It’s just that here, we go in and out of it with her and see that her illusions remain intact. Maybe we also share her sense that the good people can be fairly boring.

All you can eat

There aren’t any villains in Ann Hui’s A Simple Life, a film we first saw in Vancouver back in 2011. Roger had hoped to bring it last year, but Ann couldn’t come, as she was working on her upcoming release, The Golden Era. This year she was free to accompany the film that had a special meaning for Roger at that point in his life.

The quietness of the film is exemplary. It’s an effort to make a drama out of everyday happenings—people working, eating, sharing a home, getting sick, worrying about money, helping friends, and all the other stuff that fills most of our time. The two central characters are, as Roger’s review puts it, “two inward people” who are simple and decent. Yet Ann’s script and direction, and the playing of Deanie Yip Tak-han and Andy Lau Tak-wah, give us a full-length portrait of a relationship in which each depends on the other.

Roger Leung takes Ah-Tao, his amah, or all-purpose servant, pretty much for granted. She feeds him, watches out for his health, cleans the apartment, even packs for his business trips. When he’s not loping to and from his film shoot, he’s impassively chowing down her cooking and staring at the TV. A sudden stroke incapacitates her, and now comes the first surprise. A conventional plot would show her resisting being sent to a nursing home, but she insists on going. Having worked for Roger’s family for sixty years, Ah-Tao can’t accept being waited upon in the apartment. So she moves to a home, where most of the film takes place.

A Simple Life resists the chance to play up dramas in the facility. Thanks to a mixture of amateur actors and non-actors, the film has a documentary quality. It captures in a matter-of-fact way the grim side of the place—slack jaws, staring eyes, pervasive smells. (A small touch: Ah-Tao stuffs tissue into her nostrils when she heads to the toilet.) Mostly, however, we get a sense of the facility’s everyday routines as the seasons change. The dramas are minuscule. Occasionally the old folks snap at one another, and one visitor gets testy with her mother-in-law. One woman dies (in a bit of cinematic trickery, Ann suggests that it’s Ah-Tao), and an old man who keeps borrowing money is revealed to have a bit of a secret. It’s suggested that a pleasant young woman working at the care facility will become Roger’s new amah, but that seems not to happen. The prospect of a romance with her is evoked only to be dispelled.

Ah-Tao’s health crisis has made Roger more self-reliant, but his life has become much emptier. He seems to realize this in a late scene, when he stands in the hospital deciding how to handle Ah-Tao’s final illness. Throughout the film, food has been a multifaceted image of caring, community, friendship, childhood (Roger’s friends recall Ah-Tao cooking for them), and even the afterlife. Ah-Tao and Roger rewrite the Ecclesiastes line about what’s proper to every season by filling in favorite dishes. As he mulls over Ah-Tao’s fate, Roger is, of course, eating. But it’s cheap takeaway noodles and soda pop. This silent scene measures his, and her, loss better than any dialogue could.

The art of American agitprop

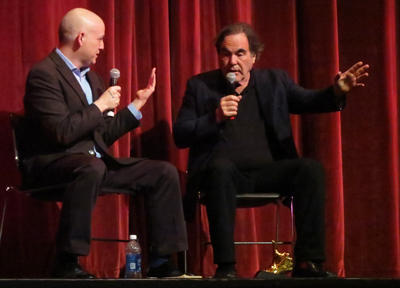

Matt Zoller Seitz and Oliver Stone on stage at the Virginia Theatre.

A Simple Life is a very quiet film. Ebertfest’s highest-profile visitors brought along two of the noisiest movies of 1989. It’s the twenty-fifth anniversary of Do The Right Thing (Roger’s review) and Born on the Fourth of July (Roger’s review), and seen in successive nights they seemed to me to put the “agitation” into agitprop.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

During the Q & A, Spike Lee reminded us that some initial reviews of the film (here shown in a gorgeous 35mm print) had warned that the film could arouse racial tensions. Odie Henderson has charted the alarmist tone of many critiques. Lee insisted, as he has for years, that he was asking questions rather than positing solutions. “We wanted the audience to determine who did the right thing.” He added that the film was, at least, true to the tensions of New York at the time, which were–and still are–unresolved.

The ending has become the most controversial part of the film. It’s here that Lee was, I think, especially forceful. The crowd in the street is aghast at the killing of Radio Raheem by a ferocious cop, but what really triggers the riot is Mookie’s act of smashing the pizzeria window. I’ve always taken this as Mookie finally choosing sides. He has sat the fence throughout–befriending one of Sal’s sons and quarreling with the other, supporting Sal in some moments but ragging him in others. Now he focuses the issue: Are property rights (Sal’s sovereignty over his business) more important than human life? Moreover, in a crisis, Mookie must ally himself with the people he lives with, not the Italian-Americans who drive in every day. It’s a courageous scene because it risks making viewers, especially white viewers, turn against that charming character, but I can’t imagine the action concluding any other way. Lee had to move the project to Universal from Paramount, where the suits wanted Mookie and Sal to hug at the end.

Staking so much on social allegory, the film sacrifices characterization. Characters tend to stand for social roles and attitudes rather than stand on their own as individuals. The actors’ performances, especially their line readings, keep the roles fresh, though, and the film still looks magnificent. I was struck this time by the extravagance of its visual style. In almost every scene Lee tweaks things pictorially through angles, color saturation, slow-motion, short and long lenses, and the like–extravagant noodlings that may be the filmic equivalent of street graffiti.

By the end, in order to underscore the confrontation of Radio Raheem and Sal, Lee and DP Ernest Dickerson go all out with clashing, steeply canted wide-angle shots. (We’ve seen a few before, but not so many together and usually not so close.) Having dialed things up pretty far, the movie has to go to 10.

In Born on the Fourth of July, Stone more or less starts at 11 and dials up from there. Beginning with boys playing soldier and shifting to an Independence Day parade that for scale and pomp would do justice to V-J Day, the movie announces itself as larger than life. The storyline is pretty straightforward, much simpler than that of Do The Right Thing. A keen young patriot fired up with JFK’s anti-Communist fervor plunges into the savage inferno of Viet Nam. Coming back haunted and paralyzed, Ron Kovic is still a fervent America-firster until he sees college kids pounded by cops during a demonstration. This sets him thinking, and eventually, after finding no solace in the fleshpots of Mexico, he returns to join the anti-war movement.

Even more than Lee, Stone sacrifices characterization and plot density to a larger message. The Kovic character arc suits Cruise, who built his early career on playing overconfident striplings who get whacked by reality. But again characterization is played down in favor of symbolic typicality. While there’s a suggestion that Ron Kovic joins the Marines partly to prove his manhood after losing a crucial wrestling match, the plot also insists that his hectoring mother and community pressure force him to live up to the model of patriotic young America. He becomes an emblem of every young man who went to prove his loyalty to Mom and apple pie.

Likewise, Ron’s almost-girlfriend in high school becomes a college activist and so their reunion–and her indifference to his concern for her–is subsumed to a larger political point. (The hippies forget the vets.) We learn almost nothing about the friend who also goes into service; when they reunite back home, their exchanges consist mostly of more reflections on the awfulness of the war. Later Cruise is betrayed, almost casually, by an activist who turns out to be a narc. But this man is scarcely identified, let alone given motives: he’s there to remind us that the cops planted moles among the movement.

What fills in for characterization is spectacle. I don’t mean vast action; Stone explained that he had quite a limited budget, and crowds were at a premium. Instead, what’s showcased, as in Do The Right Thing, is a dazzling cinematic technique.

Visiting the UW-Madison campus just before coming to Urbana for Ebertfest, Stone offered some filmmaking advice: “Tell it fast, tell it excitingly.” The excitement here comes from slamming whip pans, thunderous sound, various degrees of slow-motion, silhouettes, jerky cuts, Steadicam trailing, handheld shots, all jammed into the wide, wide frame. Every crack is filled with icons and noises–flags, whirring choppers, kids with toy guns, prancing blondes, commentative music. “Soldier Boy” plays on the supermarket Muzak when Ron is telling Donna about his plans.

By the time Ron visits the family of the comrade he accidentally killed, Stone finds another method of visual italicization: the split-focus diopter that creates slightly surreal depth.

Since so many scenes have consisted of a flurry of intensified techniques, simple over-the-shoulder reverse shots might let the excitement level drop. So a new optical device aims to deliver fresh impact in one of the film’s quietest moments.

Like Lee, Stone took the Virginia Theatre audience behind the scenes. He agreed with William Friedkin, who was originally slated to do the film: “This is as close as you’ll every come to Frank Capra.” Instead of using the shuffled time scheme of Kovic’s autobiography, Friedkin advised that “This is good corn. Write it straight through.” Hence the film breaks into distinct chapters, each about half an hour long and sometimes tagged with dates. They operate as blocks measuring phases of Ron’s conversion. Like many filmmakers of his period, Stone deliberately made each chapter pictorially distinct–the low-contrast Life-magazine colors of the opening parade versus the lava-like orange of the beachfront battle.

Stone pointed out that this film marked the beginning of his career as a figure of public controversy. Like Lee, he was attacked from many sides, and from then on he was a lightning rod. Matt Zoller Seitz (who’s preparing a book on Stone) pointed out that at the period, he was astonishingly prolific. From 1986 (Salvador, Platoon) to 1999 (Any Given Sunday), he directed twelve features, about one a year.

Lee was hyperactive as well over the same years, releasing fourteen films. And neither has stopped. Lee’s new film is the Kickstarter-funded Da Sweet Blood of Jesus, while Stone is touring to support the DVD release of his 2012 documentary series, The Untold History of the United States. Both men like to work, and more important, they’re driven by their ideas as well as their feelings. By seeking new ways to agitate us, they impart an inflammatory energy to everything they try. And in giving them a chance to share their insights and intelligence with audiences outside the Cannes-Berlin-Venice circuit, Ebertfest once again demonstrates its uniqueness. Roger would be proud.

The introductions and Q&A sessions for most of the films, as well as the morning panel discussions, have been posted on Ebertfest’s YouTube page. Program notes for each film are online; see this schedule and click on the title.

For historical background on Barry Allen’s work as an editor of syndicated TV prints, see Eric Hoyt’s new book Hollywood Vault: Film Libraries Before Home Video.

P. S. 1 May 2014: Thanks to Ramin S. Khanjani for pointing out that Ramin Bahrani had worked on other films before Man Push Cart. These included one feature he made in Iran, Biganegan (Strangers, 2000); it got only limited play in festivals and apparently a few theaters. I can’t find information about the others online, and presumably they were shorts and/or did not receive distribution. (K.T.)

Ann Hui, with Kristin, gets into the spirit of Ebertfest. David is represented in absentia by the Dots.

Around the world in a multiplex: First dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here–

My title exaggerates. There are other venues for the Vancouver International Film Festival besides the Empire Granville multiplex. There is the Pacific Cinematheque, often used for more avant-garde items; the Vancity Theatre, which screens art films and hosts industry events year-round; and the gorgeous old picture palace, the Vogue, a multiple-use venue that hosts both big screenings and gala events. But frequently we find ourselves wandering for a whole day among the Granville’s seven screens, circling the globe cinematically.

The Middle East

Four years ago we blogged about Captain Abu Raed (2007), the first Jordanian feature film in decades. This year there is The Last Friday (2011,  Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

The basic plotline is simple, with protagonist Youssef, a handsome, hard-working middle-aged man, divorced and reduced to driving a taxi prone to breakdowns, struggling to earn money for a serious operation. The cinematography was done using a Red One camera, and the resulting images are impressive. (Alabdallah often resorts, with good effect, to what David has termed planimetric compositions, those shot directly toward a flat background.) There is little dialogue, and Youssef’s struggles are conveyed by small details, visual and aural. The fact that he has tampered with his apartment block’s switch boxes to steal electricity is established early on, but by-play with the fuses he has transferred or hidden becomes an unnecessary but entertaining motif.

Perhaps the “educational” part of the film comes from Youssef’s son, a teenage wastrel who hangs out at his father’s apartment. It eventually comes out that he has stopped going to school, and Youssef has the additional burden of confronting his ex-wife to thrash out a method for dealing with their errant son.

The Last Friday treads that risky line so many independent filmmakers on small budgets take, singling out a character with a problem and showing him or her doggedly dealing with it. It takes a sure touch and an interesting character to make this work, and Alabdallah manages both, helped by Ali Suliman’s performance in the lead role.

So far undoubtedly the biggest unexpected gem this year has been the Iranian family melodrama/thriller A Respectable Family (2012). The film is the first fiction feature by documentarist Massoud Bakhshi; it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight series at Cannes and gained generally favorable reviews.

The plot concerns Arash, a professor who has lived in Paris for decades and, as a guest post at the university in his hometown of Shiraz winds down, seeks in vain for the return of his passport to allow him to return home. At the same time, a lawyer informs him and his mother that a sizable sum of money has been left to them by his estranged, abusive father. The family drama that plays out depends for effect on an extraordinarily complex and tight script with numerous abrupt turns and surprises that keep the audience as busy as in any recent Hollywood thriller. In particular, Bakhshi’s use of switches in point of view and flashbacks to the period of Arash’s youth are masterful.

Here I pass along the same advice I have given friends here at the festival in recommending the film: don’t read reviews or program notes about this film before seeing it. Everything I have read about the film gives away key pieces of information that should be kept secret.

The tone of the film, with its implicit but obvious criticism of the Iran-Iraq war and the regime that fostered it, plus the ending’s evident support for student demonstrators, make it amazing that the film could be made within Iran. It apparently has not been released within its home country and most likely won’t be. Yet the Iranian press reported calmly on its favorable reception at Cannes, as the press there usually does when national films gain prestige abroad. A story in the Teheran Times remarked: “It was a great surprise that non-Iranian filmgoers were able to relate to the Sacred Defense (1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war) and the concept of martyrdom, which are themes of the film, Mohammad Afarideh [the film’s producer] told the Persian service of the Mehr New Agency.” Afarideh added, “The film has an Iranian storyline, but the structure Bakhshi has chosen for the dialogue helps attract foreign audiences as well.”

Many in Iran and elsewhere were also surprised that A Separation could connect with western audiences in the way it did. It’s a pity that A Respectable Family is unlikely to gain such a widespread audience, but it is worth seeking out. It plays once more here in Vancouver, on October 3 at 6:45 pm in the Empire Granville 2.

Latin America

Una noche (2012) is listed in the program as a Cuban/UK/USA co-production. The Cuban contribution comes primarily from the setting and the cast–and the cooperation of the government. (Certainly it makes setting out to try and escape to the USA an unattractive prospect.) It was entirely shot in Havana and environs, and three young first-time actors play the principal roles. The director is Lucy Mulloy, making her feature debut. It is otherwise largely New York based, having been at least partially supported by the Independent Filmmaker project in its “Narrative Independent Filmmaker Lab,” which funds films with budgets of under a million dollars. Post-production seems mainly to have been done at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

Perhaps as a result of such mixed origins, Una noche manages to create a strong, Hollywood-style plot with plenty of local color. The opening shows a blonde tourist in a car, but the heroine’s voice declares that this will not be this girl’s story but her own. Quick but effective characterization sets up the close relationship between twin brother and sister. They’re poor kids from the barrio scratching a living, with Lila working as a dance-hall girl and Elio serving as a cook. Yet we are away from Lila for long stretches, becoming aware, as she is not, that Elio is gay and has a crush a fellow cook. But Raul is an obviously straight young thug, and he has talked Elio into making an attempt to cross to the USA on a raft.

Their preparations, gathering the materials and supplies they need, take us through the poverty-stricken neighborhoods, with Elio’s shiftless friends catcalling at girls and joyriding on their bikes by clinging to buses. Raul visits a dealer to buy medicine for his AIDS-stricken mother, a gaunt former beauty still turning tricks to support herself.

The action escalates as Raul accidentally injures a tourist and Lila discovers that Elio is planning to leave her and go with Raul. Mulloy deliberately downplays the ending, flashing a dedication on the screen to give us the impression that the film is over. Almost as an afterthought mixed in with the beginning of the credits, she presents brief shots showing us of the fates of the characters, filmed from a distance and without Lila’s voiceover. The Variety reviewer found the ending abrupt and “somewhat inadequately foreshadowed,” yet it seemed appropriate to me, and indeed was one of the most original touches in the film.

The North American rights to Una Noche were picked up earlier this year by Sundance Selects after the film proved a hit at the Tribeca Film Festival, winning Best New Narrative Director, Best Cinematography, and Best Actors (shared between its two male leads). Ironically, two of the young lead actors used the Tribeca festival as an occasion to request asylum in the USA.

The Antipodes

There is something comforting about the fact that, after all the success of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the prospect of a series of Avatar films  being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

Two Little Boys (2012) is based on the old getting-rid-of-an-incriminating-corpse premise, with wimpy Nige (Bret Mackenzie, left) accidentally killing a Scandinavian sports star with his car. Despite a recent quarrel, Deano (Hamish Blake), his best friend from childhood, agrees to help him out and hatches more and more devious and grisly methods for disposing of the body–and later of Nige’s roommate, pudgy, clueless Maori roommate Gav, who adds a touch of sweetness with his persistent obliviousness to the pair’s fiendish doings.

It’s a feather-weight film, but one with many funny moments. It also shows off some parts of New Zealand seldom used in films, starting off in the southernmost and westernmost city, Invercargill, and the bleakly beautiful Catlins, on the southeast coast.

Europe

From the ridiculous to the sublime. Journal de France (2012) presents a sort of professional autobiography of the great French photographer and filmmaker Raymond Depardon. The framing situation is a journey through France that Depardon takes (supposedly alone, though there is someone there to film him), photographing landscapes and villages with his big view camera (bottom). There’s a charmingly chatty scene of him photographing four aged men who had posed for him in the same spot earlier (top).

Interspersed is footage from throughout Depardon’s career. This is presented in voiceover by co-director Claudine Nougaret, the filmmaker’s partner in private life and his long-time sound recordist. Much of this footage didn’t make it into the finished documentaries, including practice shots from when Depardon was learning the trade and amazing footage of many of the major events of the late twentieth century. Depardon travelled widely, often going into war-torn areas of Africa, such as Biafra in the late 1960s. His candid footage of people in the streets of Prague during its invasion by Russian tanks in 1968 is astonishing. Also memorable is a shot of Nelson Mandela quietly sitting in a chair. Depardon asked him to sit for a minute without speaking. Without a watch, Mandela timed it to the second. He learned the trick while in prison.

One comes away with a sense of not just a man with a keen eye and a great deal of patience. Depardon’s bravery and political conscience allowed him to leave behind a legacy of images with an immediacy that brings half-forgotten historical moments to vivid life.

Now I’m off to the Granville again, to see a Japanese film and then a South Korea one. David will blog about these in a future dispatch.

Middle-Eastern crowd-pleasers in Vancouver

The Green Wave.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has offered a rich selection of Iranian and Israeli films this year. I tried to see as many as I could, and most of the screenings were packed.

Iran

The range of Iranian films, made within the country and by émigrés, reflects the paradoxes of that unhappy nation. The glory days of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s seem irrecoverable, with leading directors Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbof and his family working abroad and their younger colleagues, mostly famously Jafar Panahi, being arrested and forbidden to work. Although this national cinema has triumphed at international film festivals, forces in the regime seem determined to squelch the creative people who made that prominence possible. Yet somehow impressive films continue to be made.

Mohammad-Ali Talebi’s Wind & Fog recalls the classic Iranian films of the 1980s and early 1990s, simple stories centered around children’s quests. Talebi himself is a veteran director whose career stretches back to the mid-1980, an era when major filmmakers were skirting the censors by focusing on children and seemingly uncontroversial situations.

Wind & Fog is set in the north of Iran, during the early days of the Iran-Iraq war—a safe enough era, since the loyalty to the government during such a conflict would be unquestionable. The story concerns an eight-year-old boy who becomes mute when his mother is killed during shelling. His father takes him and his older sister to live with their grandfather in the mountains while he works elsewhere. The forested, misty hills are beautifully photographed and contrast sharply with the desert landscapes familiar from other Iranian films. The children form the core of the action as the boy struggles both with his trauma and with bullying at his new school. Both child leads gives wonderfully affecting performances, and the gradual acceptance of the strange young boy by the villagers makes for the sort of happy ending that is rare in the contemporary adult-oriented dramas reaching festivals.

One such film is Goodbye, by Mohammad Rasoulof. Although made within the Iranian industry and presumably passed by the censors, it deals remarkably directly with the efforts of its heroine, a young lawyer named Noora, to leave the country. Initially she plans to depart with her journalist husband. A black-market agency has concocted a scheme to have her become pregnant, be invited abroad to give a paper (arranged by the agency), and give birth abroad; in that way she can avoid returning to Iran.

The film stays entirely with Noora, often filming her in medium-close-up against simple, blank backgrounds. The result is an austere visual scheme of black, gray, and blue-tinged white, with an intense concentration on Noora and her increasing doubts and anxieties. The only moments of everyday life come from a motif of Noora feeding her pet turtle and coping with its tank when it begins to leak. Eventually the turtle escapes, and we never learn its fate, an obvious parallel with Noora’s situation. Possibly the authorities thought this story would be an exposé of illegal agencies fostering emigration, but our sympathies are entirely with Noora and her desire to flee.

I also caught up with A Separation, by Asghar Farhadi. David wrote about this exceptionally fine film from the Hong Kong Film Festival earlier this year. His earlier film, About Elly, is unfortunately not available on English-subtitled DVD but deserves to be released.

Maryam Keshavarz’s Circumstance is often spoken of as an Iranian film, and it gained a higher profile when it won the Audience Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. It actually was shot in Beirut and is a US/Iranian/French co-production. Based in part on Keshavarz’s own youth in Iran, it deals with two lesbian teenagers in love and the increasing opposition they face from the brother of one of them—a reformed drug addict who swings to the opposite extreme by becoming an informant for the police. Circumstance has impressive production values and is skillfully shot. I found it a bit sensationalistic, as if the director were flaunting the fact that her film was made far away from the repressive society it depicts. Moreover, its heroines looked more like glamorous models than suffering teenagers. I also wished a more plausible explanation had been given to explain how the brother gained so much power within the police establishment, to the point where he pops up everywhere and seems able to determine the outcome of every situation the reckless girls get themselves into. Indeed, the general stigma attached to homosexuality in Iranian culture is not explored; the girls’ troubles are largely reduced to a family melodrama of conflict between siblings.

The Green Wave is a documentary about the events of May and June, 2009 surrounding the suppression of the brief democratic movement that coalesced around the candidature of Mir-Hossein Mousavi. Made in Germany and directed by Ali Samadi Ahadi, the film stitches together talking-head interviews with activists who have fled Iran, simple animated sequences visualizing accounts culled from blog entries written during the events, and clandestine footage of the demonstrations and brutal crackdown that followed. Much of the clandestine footage was captured on cell phones and other amateur video formats, and the quality is often poor. Still, it provides a valuable record of the police and military firing on and beating peaceful protestors and bystanders in the streets

The film is skillfully laid out, initially conveying the atmosphere of hope that surrounded the campaigning for Mousavi, moving on to show the election itself and how it was rigged to return Ahmadinejad to the presidency, and then focusing on the horrendous crimes committed by the government against its own people. The series of events recalls the hope of the democratic demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in 1988 and the equally brutal attacks on the crowds gathered there. The hopeful attitudes of the crowds in the early days of these events provide a sad contrast with the more recent successful revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, though the Iranian government’s thorough control of its military made a similar outcome impossible. One can only trust that similar documentation of the current events in Syria are being created and will someday be assembled into an effective film like The Green Wave.

A note on This Is Not a Film

DB here:

Jafar Panahi, as you probably know and as this site noted last year, spent several weeks of 2010 in jail for “preparing an anti-government film.” While he was under house arrest in 2011, he made what has been called, for want of a better term, an “effort.” This Is Not a Film is at once funny and disturbing, playful and provocative. It takes its place in the remarkable tradition of Iranian films that oblige us to reflect on cinema–Close-Up, Salaam Cinema, Moment of Innocence, Through the Olive Trees, and Panahi’s own The Mirror. At the same time, this non-film reminds us that artistic matters are tightly intertwined with both political ideologies and the everyday lives that surround their creators.

Panahi and another distinguished director, Muhammad Rasoulof, were arrested while they were making a film in Panahi’s apartment. This Is Not a Film takes place in that space, as if to defy the government’s control over what artists may create in the privacy of their homes. While never letting us forget the political price that Panahi may have to pay—banned from filmmaking for twenty years, sentenced to prison for six—the non-film reflects more broadly on what a film is. At first Panahi seems more or less resigned to his solitude, with his family away and his big-screen TV connecting him to the world outside. He gets a call from his attorney, who suggests that his appeals may shave off some penalties, but “prison is certain.” He ponders this news, but then turns his attention to the real reason he’s recording today.

Panahi explains that he will try to read, with supplementary explanations, the script that he had intended to film. Trying to “create an image of it,” he runs yellow tape across his living-room carpet to mark out a room, a corridor, and a staircase, a skeletal spatial model recalling von Trier’s Dogville. He starts to enact the story of a girl who’s prevented from registering at a university by being locked in her room by her parents. In that reflecting-mirror fashion beloved by Iranian cinema about cinema, we’re invited to see that film, and its reenactment here, as echoing the director’s real-life situation.

The enterprise forces us to ask: Is even this partial, virtual version of an unfilmed film not itself a film? Can you shoot a script by reciting it? Up to a point, Panahi suggests yes. After a couple of tries, though, he falters and seems near tears. “If you could tell a film, then why make the film?” Rerunning a scene from Crimson Gold reminds him that during filming, a project swerves into unexpected territory: a performer’s physical being creates a texture than can’t be captured in language, let alone planned. “A film must be made before you can explain it.” This isn’t just a titillating theoretical aside. It acknowledges the Iranian cinema’s gift for discovering a spontaneous specificity in the most everyday events.

The script-reading-as-film project goes on hold, and mundane household matters intrude. It would be unfair to catalogue all of the anecdotal incidents that invade Panahi’s stronghold. (Yes, as you may have heard, an iguana and a dog named Micky are involved.) The non-film ends with Panahi’s co-director, Mojtaba Mir Tahmaseb, departing and leaving his camera behind. There follows one of those casual, piercing encounters with ordinary people that give Iranian cinema a unique glow. Without warning, the abandoned camera takes on a life of its own, suggesting that house arrest—particularly on the night of a fireworks festival—is as hard to define as a film can be.

An unhappy coda: Documentarist Mojtaba Mir Tahmaseb, the only other individual credited in This Is Not a Film, was one of six Iranian filmmakers arrested on 17 September and imprisoned. A petition on behalf of these people is online here.

Israel

Footnote.

Kristin again:

Judging by the three Israeli fiction films on offer at Vancouver, the country’s cinema is striving toward more straightforward entertainment appeal in some of its productions, though one of the three contains a strongly political subject.

Footnote is that rare comedy set in academia that actually focuses its plot around the main characters’ research. The core conflict is between a father and son, both Talmudic scholars. Eliezer Shkolnik is a stubborn, bitter old man. His lengthy, meticulous study of variant versions of the Talmud was upstaged just before its publication by a colleague, Prof. Grossmann, who made a chance discovery that proved the same conclusions. Eliezer had continued to teach, but his main scholarly claim to fame has been a single footnote in a large introductory study, acknowledging his help.

Eliezer’s son Uriel has become much more famous, based on his many popularizing books that have made him a public intellectual. Early on he is inducted into the Academy. Later, through a mistake, Eliezer receives word that he is to receive the prestigious Israel Prize, but the intended recipient is actually Uriel. Academic politics intervene when Uriel tries to decline the prize in favor of his father: it turns out that the scholar who had beaten Eliezer into print is dead set against him receiving the award. The title takes on a double meaning. In his publication on the Talmudic variants, Grossmann had not acknowledged Eliezer’s work at all, and the missing footnote in that text becomes as significant as the actual one upon which Eliezer has pinned his sense of his own accomplishment.

The film is funny and fast-paced, cleverly using voiceover and PowerPoint-style graphics to lay out the exposition about father and son. It’s apparent why Footnote won the prize for the best screenplay at Cannes. There are many droll touches, including an absurdly small conference room in which Uriel argues with university officials about denying the prize to Eliezer. There’s also a scene where a guard tries to keep Eliezer from re-entering the Israel Museum during the Academy investiture party and he adamantly refuses to provide the information that would gain him access. The whole thing has something of the air of a Coen Brothers film.

Restoration, directed by Joseph Madmony, is a somewhat more conventional family drama, though again with a father-son conflict. The main character, Yaakov Fidelman, is an expert furniture restorer in an age of disposable products. The death of his partner reveals that the business is bankrupt, and Fidelman’s son hopes to sell off the shop’s valuable premises. Fidelman’s young helper discovers that an old, seemingly worthless piano sitting in the shop is a Steinway worth a great deal—if it can be restored. The film is a slick, well-made item. It won the best-screenplay prize at Sundance this year. That surprises me a little, because it depends on an enormous coincidence. The young wastrel hired off the street as Fidelman’s assistant happens to be a promising pianist who abandoned his career path, but who could recognize the value of the old piano.

Policeman (Nadav Lapid) is the one distinctly political film, but in a novel way. It deals not with the usual threats from Palestine and from nearby countries but with masculine identity class tensions inside Israeli society. The first half concentrates on Yaron, a member of an elite anti-terrorist unit, and his bluff, muscular comradeship with his partners. A sudden switch introduces Shira, a member of a cadre of well-off Israeli terrorists determined to invade a lavish wedding and take hostage some of the country’s most wealthy industrialists. Yaron’s squad is brought in to save the situation, and he is stunned when face to face with home-grown terrorists, including a beautiful woman with a gun. It’s a fast-paced film that might do well in the U.S., though so far it apparently doesn’t have distribution there.

P.S. 17 October: Panahi’s appeal has failed and the original sentence of six years in jail and twenty years of forbidden filmmaking has been upheld. Panahi’s attorney plans to appeal to Iran’s Supreme Court. See the Variety story here.

Policeman.