Archive for the 'National cinemas: Middle East' Category

Sitting under a palm tree made of film

Jerusalema.

Kristin here–

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

The Palm Springs International Film Festival has a logo calculated to appeal to those of us who travel from snowy northern climes to attend: a palm tree composed of strips of film. As each film began and a short prologue listed the sponsors, I studied that logo and felt grateful that I was missing the frigid weather that descended upon Madison during our absence. It’s a clever design, also managing to suggest movies springing forth in abundance, which was certainly true of the festival’s offerings.

Two from the Antipodes

Most New Zealand films are set in their home country, taking advantage of its magnificent landscapes and local culture. Dean Spanley (Toa Fraser) strikes me as quite different. Based on a Lord Dunsany fantasy novella, My Talks with Dean Spanley (1936), it was mostly filmed in England and is a costume piece set in the Edwardian era. Five years ago co-productions were rare things in New Zealand, but this is a Kiwi-U.K. film with an impressive international cast. There are Englishman Jeremy Northam as the narrator and protagonist, New Zealander Sam Neill in the title role, Australian Bryan Brown (perhaps most widely known as Breaker Morant) in a supporting part, and Peter O’Toole. The latter is spoken of as a possible best supporting actor Oscar nominee, though I fear that the film is too low profile for that.

[Correction, January 26. Bryan Brown appears in Breaker Morant as Lt. Peter Handcock, not in the title role.]

Dean Spanley is a feather-light but well-told tale of Fisk, a middle-aged man who pays a tense visit to his  curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

curmudgeon of a father (played by O’Toole) once a week. For something to do, Fisk takes the old man to a lecture on reincarnation, also attended incongruously by the local preacher, Dean Spanley. A friendship develops between Fisk and Spanley as it gradually comes out that Spanley seems to be the reincarnation of the father’s beloved childhood dog. The premise is made plausible by a gradual revelation of the premise, by Neill’s performance, and by some lyrical flashbacks. The whole thing is a surprising film to have come from Fraser, whose first feature, No. 2, was set in Auckland and concerned a family of Fijian descent. Yet it seems a sign of the New Zealand cinema’s health that he could take such an unexpected turn and tackle an English literary adaptation.

Australian movieThe Black Balloon (Elissa Down) is a contemporary story set in a Sydney suburb. It’s a social-problem film, dealing with a teenage boy, Thomas, torn between his love for his severely autistic brother (a truly remarkable performance by Luke Ford) and his frustration at the effect the brother’s antics have on his own ability to fit in at his new school. The film is apparently aimed primarily at a teen audience (it won the Crystal Bear for “Generation 14plus – Best Feature Film” at the Berlin Film Festival), but the almost exclusively adult audience at Palm Springs seemed entertained and touched by it. Australian stars who have made careers abroad often return to support their native industry by acting in local films, and Toni Collette is impressive as the mother. I found it a bit of a stretch that the one sympathetic, understanding fellow student Thomas finds happens to be a gorgeous girl who also seems to have no friends among their classmates. Apart from that, it’s an entertaining and informative film.

It does have one intriguing device in the pre-credits and credits scenes: several objects in each shot contain superimposed words identifying a number of the objects visible. The idea presumably is to suggest the fact that autistic people have excellent object recognition but difficulty understanding others’ emotions. I would have liked for the labeling to continue through the film, but I suspect most other viewers wouldn’t. Admittedly that would have distracted viewers from the narrative–unless we soon got used to it, which I suspect would have happened. At any rate, it’s a catchy way to introduce the story.

Another Exodus

Watching the Moroccan film Goodbye Mothers (Mohamed Ismail) was a disconcerting experience. At first it struck me as simply old-fashioned filmmaking, with multiple plotlines concerning three Jewish families living in Morocco at a time of increasing racial tensions. The stories are the stuff of melodrama, with a beautiful Jewish girl in love with a Moroccan man, a man debating whether to abandon his long-time friend and business partner to move his family to Israel, and the partner’s childless wife, who would be devastated by the departure of the family’s children, to whom she has been a second mother. In this age of short scenes, the film bases its action largely on extended shot/reverse-shot conversations, without much moving camera or many tight close-ups.

Eventually I realized that the film looks very much as if it had been made around 1960, which is the period of the story’s action.

The similarity can’t be coincidental. As with other Moroccan films I have seen, there is considerable emphasis on the music track, and here two or three scenes use the sweeping theme from Preminger’s Exodus. Indeed, the style is occasionally reminiscent of Preminger’s work of that era, as in shots that position characters precisely across the wide screen.

There’s also the sort of depth composition with a head prominent in the foreground that one associates with widescreen 1960s films by Nicholas Ray:

There’s more cutting than Preminger would typically use, but it’s an interesting pastiche that lends some subtle overtones to the film’s action. Despite a wide range of performance styles and a somewhat schematic set of plotlines, the film is an intriguing attempt to use a throwback style to convey the period when the peaceful co-existence of Jews and Muslims in Morocco was breaking down.

The quest film grows up

A few films do not necessarily a pattern make, but I’ve been struck by some echoes among the Middle Eastern films I’ve seen at this and other festivals. When the New Iranian Cinema came to international notice in the 1980s and 1990s, one narrative premise that several films shared led them to be labeled “child quest” movies. These tended to be simple searches or journeys: a boy trying to return his friend’s school notebook (Kiarostami’s Where Is My Friend’s Home?, 1987) or a girl trying to make her way through traffic to get home after school (Panahi’s The Mirror, 1997).

Gradually disasters, natural and manmade, caused the quests to become more serious. They often still involved children, but the just as often the seekers have been adults. Kiarostami’s And Life Goes On (1991) dealt with a film director’s journey into an earthquake-devastated area to find the child actor of Where Is My Friend’s Home?, who happened to live in the worst-hit area.

More recently, though, the disasters that create quests are wars in the region. My Marlon and Brando, the first feature of Turkish director Huseyin Karabey, deals with a actress in Istanbul. She has fallen in love  with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

with an Iraqi Kurd, and when the U.S. launches its invasion of Iraq, the two are cut off from each other. Increasingly frustrated and desperate, the heroine sets out to join her lover in his home in northern Iraq, even though the convoluted set of border closings forces her to go by bus via Iran.

As she meets obstacle after obstacle and finds herself isolated in small villages where she cannot speak the local language, the film risks becoming monotonous. But audience attention is carried in part by a remarkable performance by Ayca Damgaci, who must carry every scene. At intervals we see videotaped messages sent to her by her lover. His effusive professions of love are juxtaposed with clips from the film where they had acted together, and these messages lead one to wonder just how sincere he is. Might he be leading her on through her grueling trek just to find disappointment?

My Marlon and Brando reminded me of Under the Bombs, which I wrote about from the Vancouver Film Festival. (It was also shown at Palm Springs.) There a distraught Lebanese woman travels by cab into the southern area bombed by Israel in 2006, seeking her son. Both films stress the difficulties of ordinary people’s making their way through combat areas or having to detour around them.

Another variant comes in Ramchandi Pakistani (2008), made by Mehreen Jabbar, one of several female  directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

directors who have emerged in the Middle East. The mischievous Pakistani child Ramchandi wanders away from his village in Pakistan. He accidentally crosses the border into India—a border marks only by rows of painted white stones, giving the child no indication of the danger he faces. His father follows in an attempt to find him, and both are thrown into an Indian prison for years, their unregistered status making release highly unlikely. The film then alternates between the plight of the pair and their fellow prisoners and the frantic efforts of Ramchandi’s mother to find out what has happened to them and to eke out a living while hoping for their return.

The three films deal with different conflicts: U.S.-Iraqi, Israeli-Lebanese, and Indian-Pakistani. All three stress the separations of families and lovers by hostilities and the barriers they arbitrarily create for ordinary people.

A small drama far away

In contrast, the Kazak film Tulpan (Sergei Dvortsevoy) presents flat, limitless, arid plains of southern Kazakstan, where borders and conflicts seem so far away as to be irrelevant. Asa, a veteran of the Russian navy, does not go on a quest but has a pair of local goals. He seeks to marry the elusive Tulpan and to establish his own flock of sheep. As he struggles to achieve  these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

these goals, Asa remains an assistant to his brother-in-law Ondas, a tough, seasoned herdsman who keeps finding his ewes’ newborn lambs mysteriously dead.

The film is director Dvortsevoy’s first fiction feature after a career as a documentarist, and he skillfully details the lives of Ondas and his family. There are two remarkable, squirm-inducing scenes of the births of lambs, handled in long takes that seem to make trickery impossible. Despite the hardships and disappointments, there are touches of humor, as when the local vet stops by to investigate the dead-lamb problem, accompanied by a bandaged baby camel in the side-car of his motorcycle and followed by its persistent, annoyed mother. A charming film and a crowd-pleaser.

See the film, avoid the city

During the Q&A after the screening of Jerusalema that I attended, queries from the audience tended to center around how accurate its depictions of rampant crime and violence are. Director Ralph Ziman assured us that they are quite accurate, and indeed the film is loosely based on a combination of true cases. Johannesburg, he claimed, is the world’s most violent city. Whether that’s strictly true, I don’t know, but Ziman’s film is a polished, gripping depiction of one brilliant young student’s rise and fall (and rise?) as a criminal. The script, with its complex flashback structure, is tight and fast-paced. The cinematography is consistently imaginative and beautiful. (See images at top and bottom.) I can best describe it as Michael Mann shooting a gritty Hong Kong action film, but setting it among Johannesburg gangs. The Mann influence is palpable. At one point the characters watch a scene from Heat to learn how to ambush an armored car, and Mann is among those thanked in the credits.

Jerusalema was South Africa’s submission for a nomination as the Best Foreign Film for the Oscars. Not surprisingly, it didn’t make the shortlist, being an action pic rather than the art-house fare that the Academy members favor. Its language is also a disconcerting melange of the tongues and dialects spoken in South Africa, including English. At times characters switch among languages in mid-sentence. According to Ziman, the script was written in English, and then the cast helped work out how their individual characters would speak the lines.

The basic story is familiar, with a teenager, Lucky, from Soweto accepted into a university but unable to pay his fees and intending to turn to crime temporarily to raise the requisite money. Naturally he tries to quit, only to be lured back. But Lucky uses his intelligence to work out a novel way to twist the law to his advantage, commandeering crime-ridden apartment blocks that have been allowed to slip below legal standards and buying them at bargain prices. It’s the dynamic style, though, that makes this so entertaining. It was one of my favorite films of the festival. Ziman announced that it had recently been sold for American distribution, but he would not reveal the name of the company before an official announcement. I’m not sure whether it would fit better into multiplexes or art theaters. Like so many recent films it seems to fall in between. (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and Slumdog Millionaire are only the most recent examples that come to mind.) Its subtitles make it unlikely to find a really wide audience, but its violence might be off-putting to the art-house crowd. Wherever it ends up, it’s worth looking out for.

A final thought

During the festival, I was struck a number of times by how well-made films were that came from countries where production has previously been minimal. From South Africa, Kazakstan, Morocco, and Pakistan we see films that give the impression of having been made within a well-established industry. They adeptly use conventions familiar from festival-aimed art films or from classical Hollywood-style cinema. Clearly filmmakers in such countries have been seeing a lot of movies, even if they haven’t been making very many yet. The cliché about the cinema as an international language, almost as old as the medium itself, apparently remains as true as ever.

Note: Variety‘s wrap-up of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, including the prizes awarded, can be found here.

Stepping into a movie

KT here-

This past weekend I returned from a tour of ancient sites in Jordan. I didn’t plan to see any movies during the trip, but in a way it was a movie that sent me there.

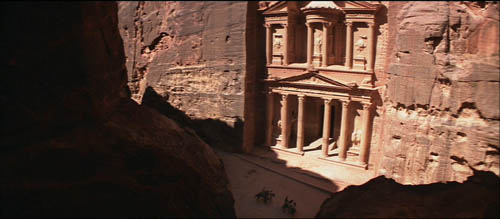

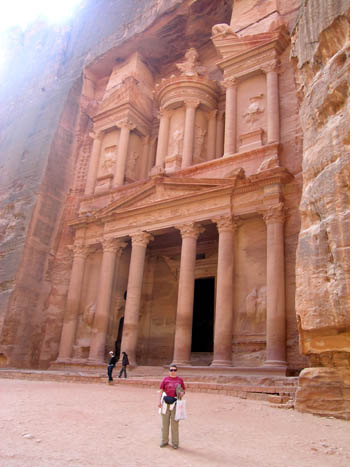

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

I suspect that, like me, many people first become aware of the ancient city of Petra when they watch the climactic scene of Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade. Indie and his companions ride through a tall, narrow canyon and emerge to confront a huge red rock-cut building (above).

That’s not a set. It was shot at Petra in southern Jordan. The canyon is real. It’s called the Siq (“shaft” in Arabic), and it’s a dramatic crack that runs for about a mile between tall, undulating cliffs of red sandstone (on the lower layers, where most of the city’s buildings were carved) and white sandstone (on the upper layers). The other structures include a theater, temples, and many tombs.

As I learned a bit more about Petra as a real place, I conceived an ambition to visit it—not for its Indiana Jones connection but because it is such an extraordinary archaeological site. In fact, last year it was voted one of the new seven wonders of the world.

I was one of seven members of a London-based tour, plus our lecturer and local guide. There are many ancient sites in Jordan, but Petra was left until the end. What, after all, could hope to follow it and not seem a let-down?

No, I didn’t go to see movies, but I discovered it’s pretty hard to escape them. References and connections tend to pop up.

We approached the entrance to Petra through the usual rows of souvenir and refreshment stalls. Some entrepreneurs were exploiting the Indiana Jones connection. Images from posters adorned coffee shops, and more than one shop had hats on sale. They weren’t really much like the famous felt fedora, being mostly of leather and not quite the right shape.

Right beside the Indiana Jones stalls, there was the Titanic Coffee Shop. My companions were mystified as to why anyone would choose that name. To me it seemed pretty obvious. American movies are popular, and why not name your shop after the most popular of them all? There was a restaurant near our hotel called Mystic Pizza. I didn’t see any images from the film on the outside, and I didn’t go inside to find out if there were any there.

Back in early October I reported on Captain Abu Raed, reportedly the first fiction feature made in Jordan in fifty years. There doesn’t seem to be any big stigma against films, though. I saw theaters and video-rental shops, some of the latter adorned with unlicensed paintings of Mickey Mouse.

Our last stop after Petra before returning to Amman was the Wadi Rum (below), an austerely beautiful landscape of desert and small, craggy mountains. The film motif followed us. Part of Lawrence of Arabia was shot there. On the spot where the real Lawrence had trod, the real Peter O’Toole sang, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

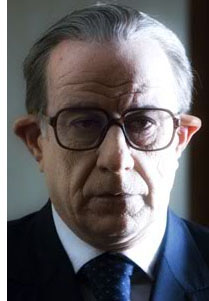

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.

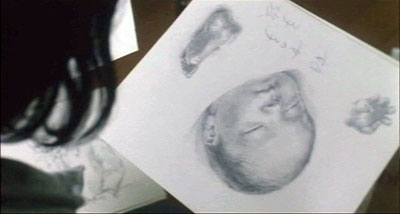

The tact of Hashigushi’s handling is on display in a late sequence. As Shozo struggles out of her depression, her family gathers for what apparently will be her grandfather’s final moments. The adults assemble to discuss the situation while children play in a room behind them. Kanao shows them sketches that they take to be of the father in his final moments.

During their discussion, the adults are distracted by the children shattering an urn in the background.

Here Hashigushi uses staging techniques I’ve discussed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Kanao’s display of his sketch favors us; it is centered and frontal. Then, after blocking the children’s play for some time, Hashigushi reveals it—centered and exposed as the adults in the foreground turn to look.

Then most of the family leaves. Hashigushi tracks in slowly to the mother’s confession of her misdeeds, and he ends the shot with a close-up of Shoko.

In a film in which the camera moves seldom and without much fanfare, this creates a simple, powerful impact and refocuses the drama on the psychologically fragile Shoko.

The film I’ve admired most across the festival is, predictably, Still Walking by Kore-eda Hirokazu. It relies on a simple situation. Grandpa and grandma celebrate a son’s death anniversary by a visit from the families of their son and daughter. Across a little more than a day, memories resurface and old tensions are replayed.

Everything unfolds quietly, and the pace is steady: none of the histrionics, both dramaturgical and stylistic, of the Danish Celebration and other psychodramas of dysfunctional families. Still Walking is a classic Japanese “home drama” in the Ozu mold. The conflicts will be muffled and nothing is likely to break the placid surface.

In a stream of vignettes Kore-eda brings each family member to life, displaying an easy mastery in shifting attention from one to another. Gradually he assembles a group portrait of a domineering father, a good-humored mother, a slightly daffy daughter, a son always compared unfavorably to his elder brother, and in-laws striving to be well-received by the grandparents without alienating their spouses. The spirit of Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story and Early Summer, hovers over specifics: a dead brother is invoked, the family poses for a picture, and the patriarch, a retired doctor, has a clinic in his home.

Kore-eda doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves; he’s often overshadowed by extroverts like Miike Takeshi. That’s partly because his is an art of quietness, shown perhaps in its most extreme form in his first feature, Maborosi (1995). At the time I thought it was only one, albeit exquisitely wrought, version of the “Asian minimalism” that sprang up in Taiwan, Japan, China, and even a bit in Hong Kong. I suspect that this trend was largely due to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpieces like Summer with Grandfather, Dust in the Wind, and City of Sadness. A Japanese critic told me that indeed Maborosi was criticized as being too Hou-like.

Now, after After Life, Distance, Nobody Knows, and Hana, Kore-eda has moved to the forefront of Japanese cinema. It seems to me that he maintains the classic shomin-geki tradition of showing the quiet joys and sadness of middle-class life while also plumbing the resources of “minimalist” mise-en-scene.

In Still Walking he works in an engaging, unfussy way. He lets us get to know and like his characters, feeling neither superior nor inferior to them. He builds up his plot more through motifs than dramatic action; a good example is the pop song that the mother loved and that gives the movie its title. The technique, spare but not austere, enforces the relaxed pacing. The film has only around 375 shots in its 111 minutes. While there are plenty of reaction shots and close-ups (the first shot shows women’s hands scraping radishes), some scenes play out in long takes rich in detail.

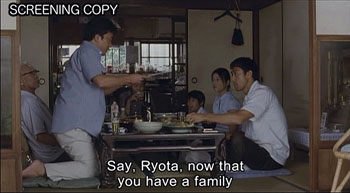

For example, in a three-minute shot early in the film, most of the family is gathered around a table.

The brother-in-law, a used-car salesman, goes out to the garden to play with the children.

Now the family members discuss the dead brother’s widow, who doesn’t come to family gatherings.

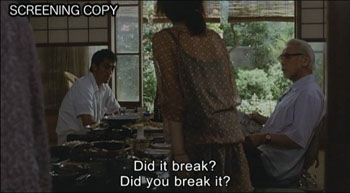

When the father declares that a widow with a child is harder to marry off, he is obtusely insulting his son Ryota’s new wife. Kore-eda marks the disruption with a cut to a reverse angle.

This generates another long take, in which Ryo’s wife Yukari deflates the tension by saying she was lucky to get him. The women then rise and clear the foreground, somewhat as the brother-in-law had by going into the garden. As the family talks, we can see him in the distance helping the kids break open a melon.

Ryo talks about his job restoring paintings. It’s clear that the father disapproves of it, wishing that Ryo, like the deceased brother, had taken up medicine. Kore-eda keeps the garden action as a secondary point of interest by having Ryo glance off occasionally.

But Ryo’s explanation of his job is cut off by the father’s abrupt rise and walk to the doorway, ordering the kids to stay away from one plant.

When the father returns to the table, the nearly two-minute long shot is replaced by a series of singles as Ryo tries to explain his work.

These shots employ one of Ozu’s staging tactics, settling two characters not directly opposite one another but one space apart. The camera seats us across from each one. As a result, the men can be posed frontally, while now we can watch where their glances go—most often, downward. The new setups let us see that the father and son don’t look at each other much.

Instead of moving to these singles right away, as most directors today would, Kore-eda has saved them as a way to articulate the next, more intense phase of the drama. It is arguably a less ostentatious way to raise the tension than the prolonged track inward that Hashigushi uses in All Around Us. (Then again, Hashigushi employs that technique at a climactic moment, while this scene we are still rather early in Kore-eda’s film.) The point is the simplicity and delicacy with which Kore-eda deploys traditional elements of craft.

It wouldn’t be fair to offer a more intensive analysis of this trim work, since it has yet to be widely seen. In the best of all worlds, it will get an American theatrical release.

In all, another wonderful Vancouver festival. See you there next year?

FlicKeR.

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.

By the end of the second hour, the remains of the army are on the run, struggling through vast snowy landscapes. Soon four survivors straggle into a ski lodge, hold the owner’s wife hostage, and face their final challenge: wave after wave of police assaults. Waiting for the inevitable outcome, the survivors spare time for grim humor: On 28 February one remarks, “I’m glad the all-out war won’t be tomorrow. Then my death anniversary could come only every four years.” And they can pause for an exercise in political discipline. After a lad takes an extra cookie, he criticizes himself. Stern reprimand follows: “That very cookie you ate is an anti-revolutionary symbol.” Unsentimental and unsparing, United Red Army is over three hours long, with not a longueur in sight.

A man parks his car to pick up some cake at a bakery. He has been away from home all night; now he’s rude to the lady behind the counter. Having bought a couple of cakes, he finds that a sinister black car has double-parked and hemmed him in. His efforts to find the owner lead to a spiral of comic and pathetic confrontations with an orphan child, burly Triads armed with whitewash, and a pimp with a distinctly bad haircut.

Creating something of a network narrative, Chung Mong-hong’s Parking in its modest way offers a cross-section of Taiwanese society, from the prostitute brought over from China to a jaunty barber who more or less controls the switch-points of the story. The ending will strike some as dovetailing all the cards a little too smoothly, but I found it satisfying, if only because it lets our haughty hero show unexpected resilience and compassion. This is only Chung’s second feature, but his work bears watching.

For once, it really is rocket science.

If you’ve already figured out the deep connections among Scientology, the aerospace industry, ritual sex magic, New Age spirituality, and the migration of Los Angeles hipsters to San Francisco in the 1950s, Mock Up on Mu won’t come as news. If, like me, you haven’t the faintest idea about the cat’s-cradle ties among these cultural phenomena, Craig Baldwin’s latest collage-essay-epic-lyric-narrative (all terms he applies to it) is the very thing you need. It’s as exuberantly peculiar as his earlier work like Tribulation 99 and Spectres of the Spectrum, flooding us with a relentless voice-over that splits off from and reconnects with the torrent of images grabbed from all manner of movies.

These earlier films had stories of a sort, swollen conspiracies and ominous coincidences that make Baldwin the eccentric cousin to Fritz Lang. But Baldwin says that these stories couldn’t really engage people, couldn’t get them to identify. Mu tells a more personalized tale. L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, has colonized the moon and sends Agent C to earth to arrange for people to be shipped up. Agent C runs afoul of Lockheed Martin, corrupt aerospace executive, and becomes attached to Jack Parsons, an early rocketeer who in the 1950s assumed the secret identity of Richard Carlson, so-so Hollywood actor. Meanwhile, Aleister Crowley rules a secret society at the center of the earth….

Or maybe not.

Actually, I won’t swear to much of what I just said. Baldwin’s phantasmagoria tests my memory, as well as plausibility. The story line is swallowed up by what he calls footnotes—swarming digressions, tangents, and flashbacks which are conjured up in imagery that shoots off in a dozen different directions. A few frames from a kiddie science movie or a grade-Z space opera, juxtaposed to Parsons’ rapid-fire account of the history of rocket testing, whiz by almost subliminally.

In any case, there are characters and a more or less linear story. But Baldwin is Baldwin, so things can’t be so simple. He has for the first time staged and shot footage of actors, and their scenes form a sort of string that you can follow. But just as crystals grow in fantastic array along a string, alien footage exfoliates out from the staged scenes. Baldwin aims, he says, at “a dialectical density.”

The result is a narrative experiment I’ve never seen before. With a simple cut, our characters are replaced by figures from other films, who become, in some spectral fashion, both alien inserts and our characters.

Confused? Here’s an example. Agent C (who will turn out to be Marjorie Cameron, muse of many West Coast artists) is riding with rocket scientist Jack Parsons. A series of shots shows them in the car’s front seat.

As the scene goes on, one character gets replaced by another.

Eventually both of our originals have been replaced.

The stand-ins can even change position as the dialogue continues uninterrupted (but always mis-synchronized).

The cuts make the inserted characters surrogates or avatars for our people, but they retain wisps of their original, enigmatic existence. They also remind us that situations like driving in a car are genre stereotypes, schemas so common that individual instances can serve as place-holders for one another. Yet the shots always return to the original actors, anchoring the associations and keeping at least one plane of the narrative moving forward.

These phantasmagoric shifts make the identity transformations in I’m Not There look labored. In Mock Up on Mu Baldwin may have found a new method of cinematic storytelling. Don’t expect Hollywood to pick it up soon.

Pulling half away

How do you tell your audience what it needs to know to understand what it’s seeing, and what it will see? A film can handle exposition (aka backstory) in several ways. Most films favor concentrated and preliminary exposition: Most information is given in one spot and quite early on. This is when you get the opening dialogue when characters say to one another: “Look, you’re my sister. You can tell me.” (Ohh…They’re sisters.) Concentrated, preliminary exposition is usually clunky, but it can be done with finesse, as in the opening soliloquy of Jerry Maguire.

The major alternative is distributed exposition, where information about the backstory is spread out, evenly or unevenly, across the film. This is common in mystery films (as when, under pressure, characters start to confess their relation to the murder victim) and in “puzzle films” like Memento, where we only gradually understand the relations among the characters. Delayed and distributed exposition in straight dramas is common in European art cinema, but it’s rare in the US, although independent films like Claire Dolan and Man Push Cart have made good use of the technique. Kristin already mentioned a similar strategy at work in Eat, for This Is My Body.

Lance Hammer’s Ballast comes garlanded with praise from festivals and major news outlets like the New York Times. For once the advance word is justified. I thought that Ballast was an exceptional intimate drama, focused almost entirely on three people and their layered relationships in a country town in the Mississippi Delta.

At this point I should mention how the three principals are connected, but part of the daring of Hammer’s film is to postpone, for almost an hour, telling you such things. He says he wanted a film that is, like the Delta, “spacious and quiet and slow.” Here the very issue of what we need to know is put into question. By blocking our knowledge of characters’ relationships, Hammer forces us to confront moments of action in a pure state. Each instant, each shot even, gains an integrity and gravity it wouldn’t have if we knew the full dramatic context.

Take the opening. After a brief, wordless prologue showing a boy in a field of crows, we’re in a vehicle pulling up at a bungalow.

The indistinct figure of a man goes to the door. Inside, a brief shot shows a black man’s face in silhouette.

Soon, the first man, who is white and weatherbeaten, is seen at the door, expressing concern for the man inside.

The white man enters, wrinkles his nose at a smell, and proceeds to another room, where a figure, turned from us, lies on a bed.

The black man continues to sit impassively before his TV, though now we can see his face more clearly.

Who are these men? What connects them? Who has died? An ordinary film would tease us with these questions but answer them fairly soon (say, in the next three or four scenes). Here, we will have to wait a considerable time to find out the answers. In the meantime, what we have registered in place of an action arc is the atmosphere of shock, sorrow, grieving, and lowering skies. And almost immediately a rather dramatic event will occur, nearly offscreen, and its causes will remain equally opaque for quite some time.