Archive for the 'National cinemas: Poland' Category

Wisconsin Fim Festival: An unexpected gem, a Zucchini, and a farewell

Clash (2016)

Kristin here:

Three more films from this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival.

Clash (Eshtebak, 2016)

David and I were intrigued by the festival’s program notes describing Egyptian director Mohamed Diab’s second feature, Clash, as taking place with the camera entirely confined to the interior of a police paddy-wagon. This kind of limitation can be a fruitful device, as it was in the Israeli film Lebanon; there the action took place inside a military tank. Clash turned out to be a real discovery, the best film I saw at the Festival (putting aside A Quiet Passion, which we had already seen at the Vancouver International Film Festival.).

Diab’s paddy-wagon has the advantage of rows of barred windows and a door, so that we can frequently see what’s happening outside. The film is set in the summer of 2013, when there were protests, often turning violent, in the wake of the ouster of President Mohamed Morsi and his replacement by the current president, Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. The truck moves through Cairo, encountering waves of such protests, and it gradually fills with a collection of people with various religions, beliefs, and cultures–supporters of Morsi’s party, the Muslim Brotherhood; others who oppose him; Christians; a homeless man; a nurse; and two journalists–with arguments and violence erupting inside the vehicle as well as outside.

Diab had to tread a fine line in his depiction of these people, since his basic theme is that they all must learn to cooperate to some extent if they hope to survive the baking heat, tear gas, gunfire, police bullying, and the anger of the mobs outside the truck. Officially the Muslim Brotherhood is considered a terrorist organization in Egypt, though Diab manages a fairly even-handed treatment of its members and supporters. Remarkably the censors did not require any changes to the film.

Just as remarkably, Diab was able to stage huge, convincingly terrifying riots in Cairo’s streets and highways (above). In a brief interview at Cannes last year, where Clash was shown in the Un Certain Regard section, he was asked if the shoot was difficult.

Very. You are risking your life because people might mistake the shoot for a protest, or might mistake you for the police. And there are haters of both, who can shoot you. It took us months of preparation. Egyptians to whom I’ve shown the film are blown away because they know that what we did is almost impossible.

He makes similar remarks in a question-and-answer session at the London Film Festival; his discussion of the film’s techniques comes from about 9:30 to 13:50.

The characters in the truck are constantly in danger, both from each other and from the rioters, and the action is absolutely riveting. There are a few lulls to vary the pace and to allow the prisoners to deal with their wounds and try to work out a strategy to protect themselves, but otherwise the suspense is maintained at a high level. A climactic scene in which rioters attack the truck, flashing laser pointers into it and trying to tip it over is handled, as Variety‘s review put it, with “brilliantly choreographed pandemonium.”

Clash was a huge success in Egypt. It was released in France in September and is already out on region 2 DVD (French subtitles only) there. Its festival life seems to be drawing to a close. It’s due for theatrical release in the UK and Ireland on April 21 and presumably will come out on Blu-ray and/or DVD. You can get a good sense of the film from the online trailers, the European one and especially the Egyptian one, though the film is not nearly so fast-cut.

My Life as a Zucchini (Ma vie de courgette, 2016)

2016 was a good year for animation. Kubo and the Two Strings, The Red Turtle, Moana, and Finding Dory were excellent as well. (I thought Zootopia was overrated.) Add My Life as a Zucchini to that list. This being Madison and the Wisconsin Film Festival being a university-sponsored event, we saw it with French subtitles rather than dubbed.

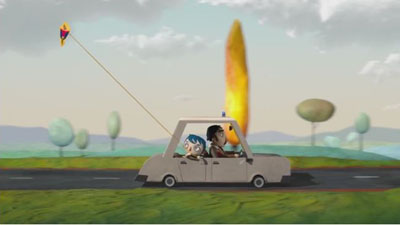

The style of the film, with its bright colors and cute, big-headed characters (above and at the bottom), makes it seem aimed at children, and the story is presented almost entirely through the viewpoints of Zucchini and the other children he meets. Yet children younger than teenagers would probably find parts of it incomprehensible or disturbing. The boys indulge in naïve but somewhat explicit speculation about sex. Zucchini’s beer-swilling mother apparently dies in an accident that he inadvertently causes, though this happens offscreen. He is taken by a sympathetic policeman to a small home for young children in the countryside. Not all are orphans, as it is made clear that one girl was taken away from her sexually abusive father and some of the others come from homes ruined by addiction or violence. Zucchini gets bullied and teased before finally being accepted.

All this makes for a strain of melancholy running through the film, but there is considerable humor to counter it, and the ending is happy.

Like Kubo, My Life as a Zucchini is puppet animation. Clearly it was done on a much lower budget, without the laser-printed changeable faces that make Laika’s characters so expressive. Charmingly, if distractingly, the clothes of the puppets occasionally shift positions, betraying the handling by the animators between frames–as when the red star on Zucchini’s T-shirt inadvertently takes on a life of its own. But on the whole, the filmmakers have used simple means to give their figures considerable expressivity.

The nomination of My Life as a Zucchini for the Best Animated Feature Oscar came as something of a surprise. Foreign films do show up in that category, but this one had its widest American release in a mere 53 theaters. It came out on February 24 and is still in 22 theaters, having grossed $286,154 as of April 6. (Presumably that does not count the two WFF screenings; the one we went to was sold out.) The DVD and Blu-ray versions are available for pre-orders on Amazon. The description says that both the original French-language soundtrack and the English-dubbed one are included.

Afterimage (Powidoki, 2016)

Afterimage premiered at the Toronto Film Festical almost exactly a month before the death of director Andrzej Wajda. It deals with the co-founder of Polish Constructivism, Wladyslaw Strzeminski, who helped create the Blok group in Warsaw in 1923. The plot covers only Strzeminski’s last years, but we get a strong sense of his entire career through gallery scenes displaying his work.

Socialist Realism was imposed upon Polish artists after the country came under the sway of the USSR in the wake of World War II. The film’s action starts with Strzeminski’s being fired in 1950 by the Ministry of Culture and Art because he refused to adhere to the doctrine. We see his stubborn resistance and the attempts by his adoring students to help him find respect and other work. Up to his death in 1952, he is oppressed by intransigent officials bent on denying him even the most demeaning jobs.

Reviewers have treated Afterimage with the respect due a veteran auteur late in a six-decade-plus career, but they deem it to lack the energy and appeal of his earlier work. Certainly compared with Wajda’s films of the 1950s and 1960s (we’ve commented briefly on two from the 1960s), Afterimage is a fairly conventional film. It’s beautifully made, as Wajda clearly had a considerable budget to recreate the historical look of Soviet-era buildings and streets of the early 1950s. To anyone unfamiliar with the impact that Socialist Realism could have on the avant-garde artists in the USSR and elsewhere starting in the 1930s, the film provides a vivid example. The film also contains an excellent performance by Boguslaw Linda, perhaps best known as the lead in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance.

Strzeminski, being the victim of persecution from almost the beginning, automatically becomes a sympathetic character. He also lost an arm and a leg in 1916 during World War I. (The budget is on display again in the fact that undetectable special effects removed Linda’s own arm and leg.) It is hinted that if he had been grievously injured in World War II, some allowances might be made, but having it happen during the Tsarist war of the pre-revolutionary era earns him no credit with the officials.

Yet Strzeminski loses some of our sympathy through his treatment of his teenage daughter Nika. She is interested in his art, closely examining the “Neoplastic Room” he helped create in the Lodz Museum–just before it is dismantled and put into storage as part of Strzeminski’s punishement. Nika also tries to help her father, cooking for him and trying to get him to cut back on smoking, but his ingracious rejection of her efforts helps drive her to live in a girls’ dormitory near her school. He remarks matter-of-factly after Nika leaves, “She will have a hard life.”

Our thanks to Graham Swindoll of Kino Lorber for help with this entry. As well, of course we owe a debt of gratitude to the WFF programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser.

My Life as a Zucchini (2016)

Adieu to Vancouver 2014

Jauja.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended this past Friday. I had hoped to post a wrap-up entry over the weekend, but illness intervened. Herewith a summary of several films I enjoyed this year.

Too clever by half

Some films are obviously and thoroughly pretentious. This year Field of Dogs (Lech Majewski, 2014) fell into that category. I had had high hopes for it, since I very much liked Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross at the 2011 festival. Unfortunately, it’s a completely different film, overcomplicated and, for me, nearly unwatchable.

Two film, however, suffered from a different problem. They had absorbing stories and interesting stylistic approaches. I enjoyed both very much–except for unwise additions, in each case unnecessary and annoying.

Stations of the Cross (Dietrich Bruggemann, Germany, 2014) revolves around Maria, an adolescent girl raised in a household where a strict, old-fashioned version of Catholicism is practiced. Bruggemann takes the not uncommon approach of filming each scene in one lengthy, and in most cases static, take. In the opening scene, a priest instructs a small class of children about to take First Communion. The camera is placed in a planimetric framing, a technique used in several shots in the film:

As the lesson continues, Maria, seated to the priest’s right, gradually emerges as the student most versed in the topics under discussion. She stays after the others leave and hints to the priest that she wants to sacrifice herself to earn a miracle for her four-year-old brother, who has never spoken. Her belief that she must deny herself virtually all pleasures, comforts, and even necessities, as well as her guilt over the slightest perceived infraction, become increasingly apparent across the narrative. Her arguments with her harsh and inconsistent mother, who dominates the family, reveal her suffering. Despite the static shots, the story is never boring, and a scathing indictment of this brand of religious extremism builds up.

The problem is that Bruggemann inserts chapter titles before each scene/shot, numbered and with the descriptions of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. This inevitably connects Maria’s sufferings to those of Jesus. Each scene contains some parallel, however tenuous, to the station that it is supposed to illustrate. I found this distracting and occasionally ludicrous, as when the title describing Christ’s being stripped of his clothing cuts to a shot of a partially undressed Maria seated on a doctor’s examining table. (Jay Weissberg’s review for Variety sees deliberate humor in the film, but as far as I could see, Bruggemann takes all this as deadly serious.) This could have been an excellent film without the insistence on allegory, but as it is, one must try to ignore the interruptions to focus on the story.

Something rather similar happens in Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, Argentina, 2014). Again there is an absorbing story, though a very different one. In nineteenth-century Patagonia, a Danish engineer is doing surveying work to help a military group determined to wipe out the indigenous population. When his daughter runs off into the forbidding desert with a young soldier, the engineer follows on his own and experiences a series of increasingly disturbing and mystifying incidents, including some that could be classed as magical realism.

This is fascinating stuff, and in the print we saw, the beautifully composed landscape shots (almost the entire film takes place out of doors) were presented in a masked format reminiscent of old lantern slides or stereoscope images (see top, the opening one-shot, long-take scene). Most of the images from this film on the internet are in a more conventional 1:66 ratio, but the masked version seems far superior. One can only hope that the video release preserves it.

It’s a lovely, evocative, disturbing film, but just as we see a shot of the protagonist disappearing into a valley in a bleak landscape of black volcanic rocks, there is a cut to an epilogue set in a beautiful Danish castle. The daughter wakes up and goes for a walk with some dogs. End of film. How this is supposed to relate to the preceding story is a mystery, and one which thoroughly undercuts the tension slowly built up over the course of the Patagonian-set story. The scene of the hero disappearing would have made a fitting ending, leaving the solution to the tale’s mysteries open-ended.

I note from a recent story in Variety that Alonso has been chosen as the second filmmaker to be hosted in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s new “Filmmaker in Residence” program. That’s good news, I think, but I hope Alonso will trust more in his story-telling ability and less in flashy tactics like this pointless epilogue.

Brief notices

One director who displays such trust is Alejandro Fernández Almendras, whose Chilean revenge tale To Kill a Man (2014) is both entertaining and morally and psychologically complex. We are almost entirely confined to the presence and knowledge of Jorge, a forest ranger who has grown accustomed to the casual violence in the neighborhood where he lives. He tries to avoid trouble, but his family is increasingly harassed by Kalule, a loathsome petty gang leader. As Jorge is mugged, his son is shot and then wrongfully imprisoned, and his house pelted with stones and threatening messages, he doggedly insists on going through the police, while his wife becomes increasingly frustrated with their lack of response.

Finally, after Jorge’s daughter is assaulted and nearly raped, he decides to act and sets out to eliminate Kalule. The film then follows his patient, careful planning, culminating in an understated but riveting long take of the truck in which Jorge has his victim trapped as he systematically sets up the mechanics of the killing. The death itself is not shown:

Hitchcock has said that in making Torn Curtain‘s big fight scene in the farmhouse, he wanted to show just how physically difficult it is to kill someone–as opposed to the seemingly effortless killings that fill American genre films. Almendras’ film is almost entirely about how difficult it is in all ways. Jorge takes a long time making his fateful decision, in executing it, in dealing with the body and evidence, and in living with what he has done. Most spectators, attuned to more conventional revenge plots and frustrated by Jorge’s initial resignation in the face of intolerable injustice, are probably cheering him on from an early point in the plot. But, as Almendras thoroughly shows us, it just isn’t that easy.

Charlie’s Country (Rolf De Heer, 2013) also centers very tightly on a protagonist beset by difficulties, but it sets a very different tone. It’s another Australian film focusing on aborigines and their problems under the rule of the white majority. Charlie is a genial elderly man living in impoverished circumstances in a village set aside for aborigines and run by local police. Their laws mystify him. His gun is taken because he cannot afford a license, and when he fashions a spear for hunting for food, it is taken away and destroyed as a dangerous weapon.

His health declines so far that the authorities send him to a hospital in a city far from his home, an apparent signal that he is dying. Instead, he escapes, lives with some street people, and finally makes his way home.

The film is entertaining enough, though it deals with familiar subject matter. It exists, though, primarily as a love letter to David Gulpilil, the most successful Australian aboriginal actor. His first film is also one of his best-known outside Australia, Walkabout, which I saw when it first came out, just after I had gotten my BA and was about to commence film-studies as a graduate student. (It’s a bit disconcerting to watch him playing an old man here and realizing that he is three years younger than me!) Gulpilil turns in an endearing performance that pretty much carries the movie.

I enjoyed and was impressed by Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsky’s Leviathan (2014), though I’m not sure it quite lives up to all the hype following its debut in competition at Cannes, where it won best screenplay. The story centers around the owner of a sprawling, dilapidated garage in a declining fishing port on Russia’s northwestern coast. He struggles to prevent a corrupt local mayor from appropriating his property illegally. (The hypocritical official wants to use the land to build a church to further his own reputation.) At the same time, the protagonist has remarried, and he must deal with his teenage son’s reluctance to accept a young stepmother.

The depiction of modern Russian society in the provinces is a grim one, albeit one displayed in sweeping landscape shots that suggest the waste of this stunning region. Many scenes involve the characters putting away great quantities of vodka. These include a hilarious set-piece in which the family and friends drive into the countryside for a drunken picnic complete with a shooting competition using portraits of historical Soviet leaders as targets.

Leviathan will be released in the USA by Sony Pictures Classics on December 31.

Papusza (Joanna Kos-Kralize and Krzysztof Kralize, 2013) is the second new black-and-white Polish film I’ve seen this year. The first was the much-heralded Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013), an austere tale of a young woman in the 1960s, about to take her vows as a nun when she learns that she comes from a Jewish family persecuted during World War I. Papusza is a more easily engaging film, with a relatively fast-moving historical drama set among Poland’s Roma (“gypsy”) population.

Papusza centers around Bronislawa Wajs, the first Roma woman to learn to read and write; she became a well-known poet nicknamed Papusza. The film adeptly balances sympathy for the Roma group at the center of the story, the victims of racial prejudice, with a clear-eyed depiction of the less savory aspects of Roma culture. Girls, kept ignorant and oppressed, are married off at a young age. The Roma society practices its own prejudices, rejecting any interactions with people outside their clan and treating non-Roma as fair game to be fleeced at any opportunity.

The lively culture of the Roma and their closeness to nature are shown in impressive landscape scenes, as in shots of the caravans on the move through bucolic countrysides or when the band sets up a camp and market outside a traditional church (below).

As of now there is no indication that the film will receive an American release. The only DVD available seems to be the Polish one, with no optional subtitles. Various small streaming services claim to be offering it, but again, possibly without subtitles and in some cases with timings that don’t correspond to the original 131 minutes.

And so another year at Vancouver has ended. As usual, we are left with the feeling that this event is one of the most pleasant ways to catch up with a huge amount of what is happening in world cinema.

Papusza

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Strands from the 1950s and 1960s

Faraon (1966).

Kristin here:

David has already posted an early report on his first full day at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. It conveys something of the overwhelming abundance of offerings at this year’s festival. Writing another entry during the festival itself proved impossible, given our packed schedules, but now we have time to catch our breath and reflect on what we were able to see.

As with the 2013 festival, I decided that the only way to navigate the many simultaneous screenings was to pick out some major threads and stick with them. I chose the retrospective of Polish widescreen films of the 1960s, that of Indian classics from the 1950s, and the third season of early Japanese talkies. Miraculously, none of these conflicted with each other, the Polish films being on mainly in the mornings, the Japanese ones directly after the lunch break, and the Indian films starting late in the afternoon.

Again, it was possible to fit in a few films from the other programs on offer, including a series of Germaine Dulac’s films, restorations of East of Eden and Rebel without a Cause, a selection of Riccardo Freda’s work, Italian contributions lifted from various anthology films of the 1950s and 1960s, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum, and many Chaplin shorts (the festival was preceded by a brief conference on Chaplin).

The annual Cento Anni Fa program, showing films from 100 years ago, has changed, in part to accommodate the fact that the transition to feature films was well underway. The series programer, Mariann Lewinsky, has also branched out. Having discovered many unknown or little-known early silents during her annual quests, she has included other brief thematic programs, such as fashion in early films. In addition, there was a lengthier selection of early films dealing with war, given that we are now in the centenary of World War I.

A Journey from Pole to Pole

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965).

To me the biggest revelation of the festival was the program of Polish anamorphic widescreen films. Representing most of the major Polish directors working in widescreen in the 1960s, these were shown in 35mm, mostly in original release prints from the period, on the big screen of the Cinema Arlecchino theatre. Despite occasional wear in the prints, they looked great.

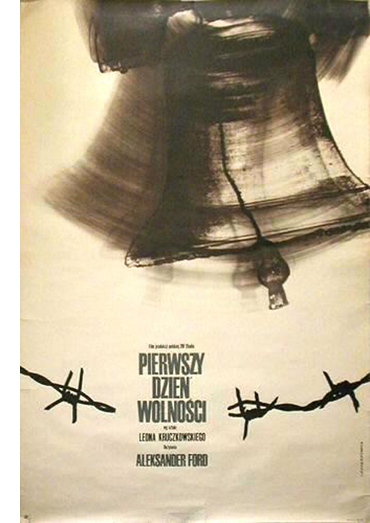

The series kicked off with Aleksander Ford’s little-known The First Day of Freedom (Perwszy dzień wolności, 1964). Like many of the films in the program, it dealt with World War II. Polish soldiers, escaped from a POW camp, enter a nearly deserted German town. They disagree on whether to help protect the civilians they encounter or participate in the general rape and pillage in the wake of the Nazi retreat. It’s a grim and realistic look at a topic seldom tackled in films about the war.

Also on the program was Andrej Munk’s Passenger (Paseżerka, 1963), left unfinished when the director was killed in a car accident. His colleagues eventually decided to assemble the film without additional footage, drawing upon still photos for some scenes and an effective voiceover filling in the action. The effort works well, and the result is a powerful examination of a Nazi death camp. The story does not concentrate on Jews but on political prisoners, implicitly communists and other rebels. The result is the sort of disguised political comment on Poland’s contemporary situation that is common in these films.

Early on, a middle-aged woman aboard a ship tells her companion about her life in as an official in the camp–a story that is contradicted when the actual scenes of her activities at the camp play out. The woman singles out a female prisoner, Marta, and rationalizes her irrational mixture of rewards and punishments as efforts to save her from the other prisoners’ fates. With its depictions of cat-and-mouse games between prisoners and captors and its references to mysterious sadistic rituals played out by the guards, the film is a powerful meditation on the camps, worthy, as Peter von Bagh’s program notes say, to sit alongside Resnais’s documentary, Night and Fog.

Among the unexpected delights of the series was Lenin in Poland (Lenin w Polsce, 1966) by Sergei Yutkevich (or, as he is credited here, Jutkevič). Yutkevich began as a member of the Soviet Montage movement, contributing a little-known, late feature, Golden Mountains (1932). Working in Poland, he managed the formidable task of humanizing Lenin in unorthodox ways. Yutkevich concentrates on the leader’s Polish exile on the eve of World War I. Framed by Lenin’s brief imprisonment on charges of espionage, the film proceeds through flashbacks to his recent activities. As portrayed by Maksim Strauch, whose resemblance to the revolutionary leader gave him a long career in numerous films, Lenin is humorous, kind, thoughtful, and a likeable protagonist. Yutkevich includes touches from the Montage movement, with some passages of quick cutting and frequent heroic framings of the protagonist.

With my interest in ancient Egypt, I was particularly curious about Faraon (Pharaoh, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966). The director tackles the unusual and obscure topic of the end of the 20th Dynasty, which led to the end of the golden age of the New Kingdom and the instability of the Third Intermediate Period. The film’s drama comes from the real-life conflict between the impoverished, weakened monarch and the wealthy, powerful priests of Amun in Thebes. I’m not sure how well an audience not familiar with this era would follow the plot, even simplified as it is. There are some remarkable crowd scenes, as at the top of this entry, when Herhor, the chief of the priests, rallies the crowd against the pharaoh. Still, I did not find the story engaging. Presumably it was a covert commentary on politics in Poland at the time.

The best-known of Polish directors, Andrzej Wajda, was represented by two films. One was the earliest film shown in the series, Samson, from 1961. It concerns a young Jewish man who is lured to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and spends most of the film dodging the police by moving from one temporary haven to another. Wajda creates a compelling depiction of the ghetto early on, and I wished he had stayed in that environment longer.

My favorite film of the festival was Wajda’s little-known Ashes (Popioły [not to be confused with Ashes and Diamonds], 1965), an epic tale of the Napoleonic wars and Poland’s unwise participation in them on the side of the French. The protagonist, Rafal Olbromski, is a naive young nobleman from a rural area, a Candide-like figure whom we follow as he leaves his estate to go to war and moves from locale to locale, manipulated by more sophisticated characters. The result is a dizzying succession of battle scenes, largely without any context being established, punctuated by visits to the estates of those who are backing the Polish participation in Napoleon’s conquests. Wajda seemed to have had nearly limitless funds for the film, and the battle scenes are monumental.

Far less obscure is Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony a Saragossie, 1965), a cult item among film buffs and reputedly one of Luis Buñuel’s favorite films. It’s a complex, surreal tale of a wandering soldier of the 18th Century who passes the gibbets of two executed men in a bleak Spanish landscape and enters a mysterious inn. There he encounters a large bound manuscript that leads him into a world of shifting fantasy and tales within tales within tales. Has’s was certainly one of the most humorous and entertaining films in the series.

The latest film in the program, Adventure with a Song (Przygoda z piosenka, Stanisław Bareja, 1969), was radically different from the others and provided a look at popular Polish cinema of the 1960s. Bareja was a successful director of comedies and musicals. This one follows a young singer who wins a local singing contest with the improbably named “The Donkey Had Two Troughs,” and decides to head for a professional career in Paris. The filmmakers’ attempts to replicate the Mod styles and garish colors of the 1960s in the West yield an incongruous and awkward but fascinating film .

The one disadvantage of seeing these vintage distribution prints (mostly with English subtitles) was that some were abridged versions, occasionally radically so. Samson, The First Days of Freedom, Adventure with a Song, and, inevitably Passenger were shown complete. Judging by imdb’s timings, however, others were missing significant amounts footage: Ashes (shown at 169′, originally 234′), The Saragossa Manuscript (155′ vs. 175′), Pharaoh (149′ vs. 180′).

Recently there seems to be a revival of interest in Polish classic films. Martin Scorsese has curated a large program that is currently touring the US with digital copies of restored films. (For links to numerous articles on the series and the restorations, see its Facebook page.) I hope that some enterprising company will issue the complete versions of these Polish classics in their proper widescreen ratios. Ashes is a particularly good candidate for such treatment. Having sat through it once at nearly three hours, I would happily watch it at closer to four.

Worthy of restoration

There’s a growing interest in recent Indian films, at least in the USA. Our biggest local multiplex nearly always devotes  one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

One reason is because many of these classics still await restoration. While most programs shown in Bologna consist of newly restored prints, this series was titled “The Golden 50s: India’s Endangered Classics.” Each of the features was accompanied by an episode of “Indian News Review,” a newsreel that for years was shown in film programs across India. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, curated the series and introduced each film, emphasizing that even the eight classics selected for the program are in danger if not properly restored soon.

The need was evident from the prints. Some were old distribution prints, but three of the films could only be shown on Blu-ray. Even under these conditions, however, the range and quality of Indian cinema of the 1950s was apparent.

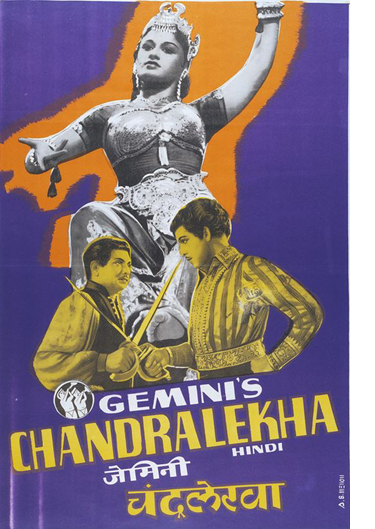

The earliest film in the series, Chandralekha (S. S. Vasan), was made a little before that decade, in 1948. Its presence stems from its crucial importance in Indian film history. It was the first big, successful Indian musical of the post-colonial era and set the pattern for many of the country’s subsequent films. The story has a fairy-tale setting, with a good and an evil brother fighting over the throne of their father’s kingdom and also for the hand of the beautiful Chandralekha. The rambling plot includes lots of songs and dance numbers, leading up to the climactic, legendary Drum Dance (below right), with dozens of dancers atop rows of enormous drums. It lives up to expectations. (For more on Chandralekha, see fellow Ritrovato fan Antii Alanen’s epic blog post.)

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

One of the great Indian directors, Ritwik Ghatak, has become somewhat familiar in the West, thanks in part to the British Film Institute’s issuing two of his masterpieces on DVD: A River Called Titas and The Cloud-Capped Star. The series at Bologna included Ghatak’s first feature, Ajantrik (1957). It is set among the poverty-stricken Oraons, an isolated population in Central India, and follows a man who is devoted to his dilapidated taxi, which he manages to hold together well enough to supply him a marginal living. He has come to think of the car as a human companion. (Accordingly, the title means, roughly, “not mechanical,” although for western distribution it was given the unenticing title Pathetic Fallacy.) Though Ajantrik is not a major film on the level of the others in the program, it was good to have the rare opportunity to see Ghatak’s first film.

The star of the series was undoubtedly an equally respected director, Guru Dutt. Two of his films, in both of which he also starred, were shown. One of his finest films, Pyaasa (The Thirsty One, 1957), was perhaps the best film of the program. Dutt is considered to have integrated the conventional song episodes of Indian cinema into his films more skillfully and in more original ways than other directors.

Dutt plays a great but unappreciated poet whose work is ignored by the intelligentsia of his own class. He wanders in despair among the poor and outcast, for whom he has great sympathy. In one haunting scene, he walks through a brothel district and sings of his despair for humanity (below). Early in the film he meets a prostitute who appreciates his poetry and falls in love with him. Only after the poet’s apparent death does his work become widely loved among the the common people, but his reputation is exploited by his hypocritical family and publisher.

Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), was also shown. Again Dutt plays an unappreciated artist. A film director divorces his wife and becomes the target of gossip when he casts a beautiful young actress in his next movie. His personal misery affects his ability to direct, and after a slow slide into alcoholism, he loses his job. The plot allows Dutt to express self-pity more obviously than in Pyaasa, and the comic scenes with his ex-wife’s family strike an odd tone in such a grim story. Kaagaz Ke Phool was not a success, and Dutt gave up filmmaking altogether, dying of an overdose of sleeping pills five years later. As Dungparapur pointed out, he was one of several important Indian filmmakers who died rather young, which makes the rescue of these classics all the more essential.

Pyaasa (1957).