Archive for the 'National cinemas: Russia and USSR' Category

The ten best films of … 1931

M (1931)

Kristin here:

Our regular readers know that this annual series began as a simple salute to 1917, the year in which the basic norms of the classical Hollywood cinema definitively gelled. Starting in 2008, it became the “The 10 best films of …” list. It has stood in for the year-end ten-best lists which critics and reviewers feel obligated to concoct but which we avoid.

1931, I think, was a slight improvement on the rather lackluster 1930. A small handful of filmmakers mastered the “talkies” and made movies that look and sound as if they could have been made years later. These are the first four films below. It was a little harder to fill in the list beyond them. It’s is full of familiar classics, with a film or two that will probably unknown to many. I always try to include at least one worthy out-of-the-way title.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, and 1930

M

I remember seeing M as a grad student, or maybe even an undergraduate, and being horribly disappointed. This was a masterpiece? Actually it was only a semblance of one. In the 1970s a poor, incomplete 16mm print with as sparse a set of subtitles as I think I’ve ever seen was in circulation. The wit and brilliance of Fritz Lang’s sound links and voiceovers were largely lost, as were the sharp images now evident in the restored version. Even restored, as the introductory titles tell us, it is missing 212 meters. Fortunately that’s only .4% of the total, and the narrative progression is so smooth and absorbing that it’s hard to imagine that anything could be missing.

The story concerns a child-murderer terrorizing a city and the parallel searches for him by the police and by the organized underworld, the activities of which are being hindered by constant police searches and raids. At one point Lang famously intercuts a meeting of city officials with one of a group of gangsters. Parallels are created by matched gestures between space but also by one line being started by a character at one meeting and picked up by one at the other. Lang races through exposition by having the voiceover of a phone conversation between officials continuing over shots of the investigation in various spaces.

He uses sonic motifs as well. The killer compulsively whistled a Grieg tune as he lures his victims, but whistles come back time and again. Police whistles signal the raid on a basement tavern, and the beggars who tail their suspect signal each other with whistles–heard by the killer, who flees into an empty office building and ends up trapped there (top).

There’s a lot of offscreen sound in this film. The raid on the tavern cuts around to various parts of the space, as when we briefly follow a crook who tries to sneak out (above) while the protests of the crowd and the whistles and shouts of the police are heard off. One might think that all this is to avoid having to lip-sync the sound with the characters speaking–but when he does show the speaker, the sync is perfect. It’s another instance, I think, of Lang using sound to cram a lot of action or information into a short stretch of time. The thwarted crook is just a bit of comic relief, something Lang injects at intervals into this grim narrative.

Back in 2012, when I participated in Sight & Sound‘s poll of critics and academics for the ten best films of all time, I put M on the list. Counting 2021, it is the third film from that list that I have included in this one: The General in 2016, The Passion of Joan of Arc in 2018, and now M. The next one won’t show up for eight years (hint: Renoir made it in 1939), assuming I’m still doing this list at that point.

If you’ve never seen M, make sure you don’t watch an older print! The restored version is on Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection in the US and Eureka! in the UK.

Le Million

René Clair made two film classics in 1931, À nous la liberté and Le Million. I find the latter a better film in that it’s more complex and lively. À nous la liberté, which focuses on only two characters who spend a stretch of the film apart, has a rather thin narrative. Le Million, on the other hand, involves a large cast of amusing characters and constantly bubbles with dances, chases, and farcical situations. Indeed, early on it cites the chase scenes of early cinema when police pursue the kindly thief, Père Tulip, over the rooftops.

The sets were created by the great French film designer, Lazare Meerson (who also did the more austere sets of À nous la liberté). The interiors often have soft, hazy backgrounds (top of this section) apparently done partly by painting and partly with real objects behind scrims. These give a stylized quality appropriate to a classic farce situation: the debt-ridden artist protagonist Michel frantically searches for a jacket holding a winning lottery ticket as the jacket goes from hand to hand. At one point crossing hallways permit two chases–the police after Tulip, the creditors after Michel–to pass through each other.

David and I taught Le Million in an introductory film class back in the 1970s. I hadn’t seen it since, but it lived up to my fond memories of it. As cheerful a film as one could find for what promises to be another year short on cheerfulness.

Le Million is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection. The description says that the lyrics are all translated here for the first time.

Arrowsmith

Early as it is, Arrowsmith is surely one of Fords’s great films of the 1930s. It’s an adaptation of Sinclair Lewis’ 1925 novel of the same name. (Lewis won a Pulitzer for it but refused to accept the award.) The plot centers around Martin Arrowsmith (Ronald Colman), who starts as a medical student eager to establish a reputation and help discover cures for various plagues. He marries a charmingly impertinent nurse Leora (Helen Hayes), who supports him in his efforts.

The style of the film is distinctly flashy in its lighting, depth shots, and set design. It looks like what we tend to think of as Wellesian–though many of these techniques could instead by dubbed Fordian.

There are dramatic chiaroscuro effects as when Arrowsmith arrives home one evening, discouraged, and Leora sympathizes with him. The figures are side-lit with illumination coming from the kitchen, and Arrowsmith becomes a silhouette once he sits down.

The depth shots are equally impressive. A spectacular high angle (top of this section) shows three levels of a ship’s interior, with Sondelius, a medical expert, shouting up to the captain that he has discovered bubonic plague onboard. A less flashy but highly intense shot shows Leora’s death from bubonic plague. The long take is filmed with what David terms “aperture framing,” with Leora placed far off-center and relatively far from the camera, framed in the arms of the foreground rocking chair. It’s the same chair in which she sat when she smoked a cigarette contaminated with one of her husband’s plague samples. It’s a brilliant way to emphasize that she dies alone, with the bright open door at the center of converging lines of the set stressing that her husband does not suddenly appear, as we might expect, to comfort her.

Other more casual uses of depth with prominent foregrounds include a shot of Arrowsmith exiting his laboratory with beakers, bottles, and other equipment dwarfing him (below right).

Note also the prominent ceiling on the sets in the image on the left above. The notion that Citizen Kane was the first Hollywood film to use ceilings on sets has long been discredited, and here’s a good example of why. In general, Richard Day’s art direction combines with the cinematography to create powerful images, as in the hallway of the McGurk Institute, where Arrowsmith gains a research post.

We know that Welles was influenced by Ford’s work, but he primarily stresses Stagecoach as a film he watched repeatedly before making Citizen Kane. Arrowsmith, however, actually looks more like Kane than Stagecoach does. Did Welles and/or Gregg Toland see it? Very likely at least one of them did. There seems to be no record of Welles having said he saw it, but in 1938 he wrote and performed the title role in a radio version of Arrowsmith that had Hayes repeating her role as Leora.

Moreover, Arrowsmith was produced by Samuel Goldwyn. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Toland was making films there, including Eddie Cantor comedies (Whoopee!, 1930) and two crime dramas starring Colman (Bulldog Drummond, 1929, and Raffles, 1930). It seems implausible that he would not have seen Arrowsmith.

All this is not to say that Arrowsmith was the first film to play with depth and chiaroscuro. As David pointed out in a 2010 blog entry, such ideas were developing in Hollywood during the 1920s, and William Cameron Menzies in particular experimented with them. There David wrote, “The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment.” True enough, but I think Arrowsmith uses them more consistently.

So far Arrowsmith has not been released on Blu-ray, but the MGM DVD has surprisingly good visual quality for a film from this period. (Amazingly enough, you can still buy new VHS copies on Amazon.)

Kameradschaft

Like Clair, G. W. Pabst directed two classic films in 1931, Kameradschaft (“Comradeship”) and The Threepenny Opera. The former is a network narrative, cutting among several characters or small groups of characters as they react to a mine disaster.

The story is set in two villages on either side of a French-German border. Each is a mining town, exploiting what is actually the same rambling mine that has walls and bars in multiple tunnels marking the end of the German portion and the beginning of the French one. When escaping gas triggers a fire and ceiling collapses on the French side, two truckloads of German miners volunteer to go and help the rescue teams.

As the title suggests, the film stresses the theme of solidarity among the miners, though Pabst doesn’t paint an entirely rosy picture of this. The German miners coming off their shift argue about whether they should assist their French counterparts, and many declare that it’s none of their business. Pabst stages the debate in a visually interesting locale, the changing room where the mining outfits of the men are stored on ropes or wires up by the ceiling (above and below, left). The leader of the group which goes to help with the rescue is played by Ernst Busch, a well-known Communist actor-singer who was also in the original stage version of The Threepenny Opera and Pabst’s adaptation, as well as Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe (1932), from Brecht’s script. His presence as one of the main characters in the network plot–and the one who spurs others to volunteer as rescuers–helps give Kameradschaft a distinctly leftist tone.

As with many other films set in coal mines, the mine itself was an elaborate and convincing studio set (above right). One collapsing area of a mine looks much like another, but Pabst found ways to vary the action from scene to scene. Variety is added through a contrast in the main characters being followed. An old ex-miner sneaks into the mine to search for his grandson. Three German miners who didn’t go in the trucks to the French side decide to make a rescue effort on their own, breaking through the barred underground border to do so. They end up alongside the old miner and his grandson, trapped in the underground stable, where the presence of a placid but doomed horse adds a poignancy to the scene. At intervals the drama going on among the mothers, wives, and sweethearts of the French miners clustered at the gates is shown.

The weaving together of the various threads of action creates a strong sense of suspense. No one character can be singled out as the protagonist, the one who might be expected to survive. Some miners and rescuers escape, but there are many who die or suffer serious injuries.

Despite the emphasis on the comradeship of miner of both nationalities, the Germans definitely come off better. Their rescue team is well-equipped and efficient, while the French workers deal with problems like an elevator being out of commission. It probably would never have occurred to Pabst and the others involved to make a film where French miners help rescue German ones–and it probably would not have been greenlit by the production company if they had. On the level of the individual miners’ actions, however, the notion of working-class solidarity comes across.

Kameradschaft is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Tabu: A Story of the South Seas

Tabu was Murnau’s final film. (The opening scene of the hero fishing with his friends was shot by intended co-director Robert Flaherty, who soon quit due to disagreements with Murnau.) It deals with Matahi and Reri, who live a joyful life on unspoiled Bora Bora until an elderly man from a nearby island arrives and announces that the “Virgin sacred to our gods” has died, and Reri is to be her successor. Matahi rescues her, and the two flee to another island which has been colonized by the French. They have established a pearl fishery and hire local men to dive for pearls. Matahi proves expert at this, but not understanding what money is, he soon gets himself deep into debt by signing IOUs.

Rather than using Hollywood stars, Murnau cast local unprofessionals. As the credits announce, “only native-born South Sea islanders appear in this picture with a few half-castes and Chinese.”

The two leads are appealing characters, and the images take advantage of the unspoiled scenery of Bora Bora (below left). Floyd Crosby earned an Oscar for Tabu‘s cinematography.

Tabu is a far cry from Murnau’s German films, but Nosfertu‘s famous shot of the vampire’s ship sailing eerily into the frame from offscreen is echoed as a motif here (below right).

The original version released by Paramount was released on DVD by Milestone. A restoration of the original cut of the film is available on DVD and Blu-ray from Kino Classics in the US and Eureka! in the UK, both with numerous supplements. A helpful comparison of these versions is available here.

La Chienne

I think it is safe to say that most critics and historians consider La Chienne the film where Renoir’s distinctive traits as a director began to emerge. I have seen most of the early Renoirs, but long enough ago that I can’t make a comparison. It does seem to me, though, that it is quite different from his previous work.

Maurice Legrand, the protagonist played by Michel Simon, is the most Renoirian character. He is a mild-mannered accountant married to a termagant who nags him constantly and forces him to remove from their apartment the paintings and the equipment he uses for his hobby. This sets off the events which follow, as Legrand hangs the paintings in the apartment of a prostitute, Lulu, with whom he has fallen in love. Her pimp Dédé concocts a scheme to sell the paintings, which he passes off to a dealer as the product of an American painter named Clara Wood. Even when Lulu explains what happened to the paintings, Legrand is so besotted that he raises no objections.

Although “la chienne” of the title is clearly Lulu, it might refer to Adèle Legrand as well. “Chienne” is more-or-less the equivalent of the English “bitch,” meaning both a female dog and an obnoxious woman, which Adèle certainly is. In their first scene together, she berates Legrand at length, comparing him unfavorably with her first husband, whose portrait in military uniform looms over them (above). Legrand does not rebel but answers in quiet sarcastic comments and ultimately obeys her order about the paintings.

In French, “la chienne” has the additional meaning of a prostitute, clearly referring to Lulu. Legrand is trapped between a constantly angry wife and a prostitute skilled in behaving in a docile fashion, pretending, as she finally admits, to love him solely in order to maintain the flow of money from the paintings. This admission finally drives him to fight back, killing Lulu. He ends up as a jovial tramp, foreshadowing Simon’s later role as Boudu in what is arguably Renoir’s first true masterpiece.

Stylistically the film does not strongly resemble Renoir’s major films of the mid- to late 1930s. Still, the scene in which Dédé and his friend approach an art dealer in their first attempt to sell one of Legrand’s paintings consists of a longish take of nearly two minutes, with staging in depth (below) when the dealer returns from a search and a track-in to a closer framing for the negotiations. Also, the film starts as a puppet show, with puppets introducing the main characters, whose images are superimposed over the little stage (bottom). This looks far forward to his final film, The Little Theatre of Jean Renoir (1970).

La Chienne is available on Blu-ray and DVD from The Criterion Collection.

Tokyo Chorus

Last year Yasujiro Ozu made his first appearance on this list for That Night’s Wife. This year it’s Tokyo Chorus (or Chorus of Tokyo). With sound barely established in Japan, Ozu made this and several subsequent films silent.

As the Criterion Collection liner notes explain, Tokyo Chorus combines the three genres Ozu had worked in before: the student comedy, the salaryman film, and the domestic drama. The student comedy subject gets disposed of early on, with the first scene showing the a comically strict teacher scrutinizing his class, lined up military-style; the protagonist, Shinji, tries some mild defiance by being late and showing off (below left).

Soon he has graduated, though, and is working in an office where the employees are awaiting their year-end bonuses. Just as quickly, Shinji is fired for protesting when an elderly colleague is fired just before his retirement and pension payments.

The rest of the film seems like a practice piece for I Was Born, But … (1932) and other Ozu films involving bratty kids who make demands on their parents. In this case Shinji’s son insists that his father buy him a bicycle and pesters him until he finally gets it (above right). As in the later film, Shinji is humiliated by having to take a job helping his old teacher to publicize his curry cafe.

Ozu’s growing mastery of editing for comedy is shown off in the early scene when the office employees try to find out how big a bonus their colleagues have received. Shinji sneaks away to the restroom to open his envelope, pretending he has gone to use a urinal. A low-height shot shows another man coming in, with the swinging doors of the urinal area showing him only from the waist down. Shinji, just about to open his envelope, glances off and sees him. A reverse shot shows the colleague stopping and staring, clearly more interested in Shinji’s bonus than in using the urinals. Shinji gives up, pretends he is just there to relieve himself, and a final shot shows him departing still not knowing how big his bonus is.

By this point, Ozu has mastered balancing comedy and pathos, a mixture of tones that will reappear in many of his future masterpieces.

Tokyo Chorus is has been released on DVD, appropriately enough along with two of those future masterpieces, I Was Born, But … and Passing Fancy (1933), by The Criterion Collection.

City Lights

I must admit that I do not admire City Lights as much as The Gold Rush and The Circus, which featured in my ten-best lists of 1925 and 1928. I think it has some narrative problems.

For one thing, the blind flower seller as a love interest is pretty passive and doesn’t allow many opportunities for generating humor. In The Gold Rush, Chaplin had the inspiration to introduce a dream sequence about the dance-hall girls, including his beloved Georgia, coming to dinner with him. He then inserted his classic gag, the dance of the rolls. Much of the action in The Circus involves the heroine, as with the magic act into which the Tramp stumbles. The flower seller mainly generates pathos, right up to the ambiguous ending. (I have seen commentators take the ending as a clear indication of a budding romance between the pair, but I think we get no clear indication that her gratitude for the help the Tramp has provided will blossom into love.)

Chaplin needed to fill out the film with action beyond the few scenes involving the flower seller. Much of the action involves the Tramp’s on-again, off-again friendship with the eccentric millionaire, which is a weak premise to carry so much of the narrative. This character treats the Tramp as his closest buddy when drunk but then fails to recognize him when sober. This happens three separate times and gets a bit repetitious in a way not seen in other Chaplin films. The main contributions of the millionaire to the plot are to give the flower seller the impression that the Tramp who buys her flowers is a wealthy man and to give the Tramp the money for the flower seller’s eye-restoring treatment. The character of the millionaire does create some humorous bits, as when the pair eat spaghetti and the Tramp gets a curly streamer mixed in with his and keeps on eating it. I can’t help contrasting the millionaire with the Mack Swain character in The Gold Rush, whose interactions with the Tramp generate so many hilarious gags.

There are admittedly other funny scenes, especially early on, when the Tramp is discovered asleep on the lap of a statue being unveiled before a crowd or when he becomes a street cleaner to earn money for the flower seller and is immediately confronted with a group of horses and, as a topper, an elephant passes.

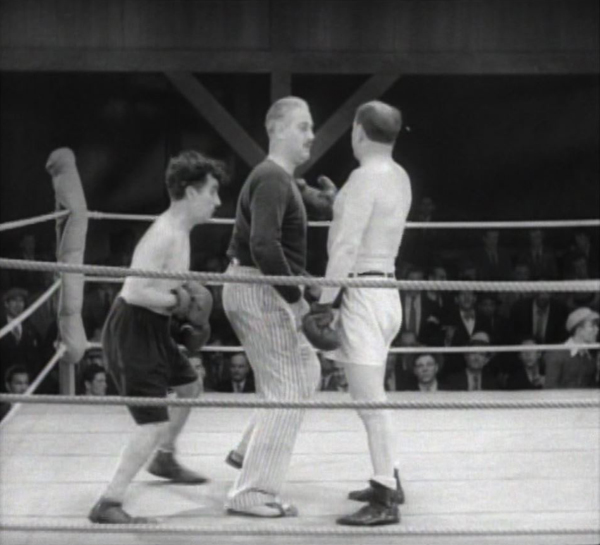

Later on in the film, though, the plot premise of earning money to help the flower seller have an operation to restore her sight generates one of the funniest scenes in all of Chaplin’s work. He agrees to participate in a fixed boxing match, with his opponent going easy on him and the two splitting the purse. The opponent is replaced by a tough guy who clearly has no intention of playing nice. The Tramp’s tactics to avoid being beaten up involve dancing around directly behind the referee at first (top of this section) and then, in a dazzling bit of choreography, the three figures move around the ring, changing places repeatedly so that the Tramp is sometimes behind the referee, sometimes behind his opponent, and so on. It is reminiscent of the scenes in the hall of mirrors as the Tramp is chased by a pickpocket and then by a policeman in The Circus, with the characters and their reflections dodging in and out of view.

Chaplin famously refused to allow spoken dialogue in his film, despite the fact that the transition to sound was well established in the USA by 1931. He restricted the track to music and sound effects, a tactic he carried over to Modern Times as late as 1936, though there the Tramp’s voice is heard for the first and last time singing a nonsense song. Chaplin retired his long-time character thereafter.

City Lights is available on DVD and Blu-ray from The Criterion Collection.

Odna (Alone)

When I was in graduate school, the only film by Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg widely known outside the Soviet Union was their 1926 adaptation of The Cloak, which appeared in my best-ten list for that year. Then people discovered, to some extent, The New Babylon, which appeared in the entry for 1929. I suspect that few people have seen, or even heard of, their marvelous first sound film, Odna.

It was planned as a silent film, but delays permitted the use of sound technology to add a track to it. The main element of the track is Dimitri Shostakovich’s musical accompaniment. (He had also composed the musical accompaniment for The New Babylon.) The music comments on the action, often in a mocking way. Occasionally there are sound effects, and very occasionally, brief lines of dialogue, recorded and added after the filming.

The plot centers around a young teacher fresh out of school, Yelena Kuzmina (played by Yelena Kuzmina, who also played the protagonist of The New Babylon).

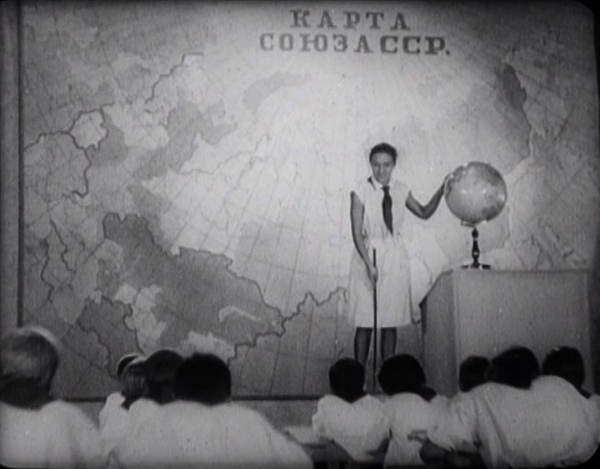

The first section of the film is played with an absurdly jolly exuberance. Yelena is engaged to a handsome young man, and a lively montage of shots shows her visions of the ideal life she plans to lead with him in Moscow, including window-shopping for expensive sets of dinner crockery, playing a musical duet at a cafe (below left), and teaching attentive children seated in neat rows in a well-equipped classroom (top of section). Shostakovich’s music is ridiculously cheerful, and a song about how beautiful life will be plays over a shot of Kuzmina’s fatuous grin (below right).

The tone switches abruptly as Kuzmina receives an assignment to a teaching post in a remote, mountainous primitive district of Siberia.

Devastated, she lodges a complaint, which seems likely to succeed. An elderly man in the office tells her that she’s right to try to change her assignment (below left). She erupts, “I’m going anyway!” This is one of the few post-dubbed lines.

Upon arrival in the Siberian district, she encounters a dead horse’s skin on display (below right); this returns as a motif to emphasize how primitive and in need of education the area is. At first the villagers react with indifference or antagonism, seeing no point in having their children go to school. Oddly enough, the local Soviet official is lazy and also indifferent, leaving her alone with no aid in convincing the villagers to accept her. (This negative depiction of the Soviet official later got the film banned, despite its considerable popularity upon its initial release.)

Apart from encouraging teachers to accept whatever school they were assigned to, the film has the anti-Kulak theme that was common in Soviet films about the countryside. (See the discussion of Eisenstein’s The General Line in the 1929 entry.) A wealthy local landowner has secretly sold off the sheep that technically belong in common to the villagers, whose main source of income is the wool. Kuzmina exposes the theft and helps the local people resist it, thus finally gaining their trust.

The next-to-last reel of the film, in which the landowner tries to kill Kuzmina, is missing. A restored version of the film accompanied by a reconstruction of the Shostakovich score was released on Dutch and German DVDs in 2007. (The frames here are from the Dutch DVD.) It includes a long series of intertitles describing action in the missing reel, drawn-out so as to match the length of the music, which does survive. As far as I can tell, these DVDs are no longer available. I am reluctant to recommend a version on YouTube, derived from the German DVD and superimposing English subtitles on German ones, on top of Russian intertitles. It does seem to be the only widely available way to see the film at this point, so for those who can put up with the clutter and the poor quality of the online version, it is here. A complete recording of the charming music is still available.

La Petite Lise (1930)

My tenth film is a holdover from last year. I consider Jean Grémillon’s La petite Lise a film worthy of the top-ten list, but when compiling last year’s list I somehow misremembered it as being from 1931. It just goes to show that one should double-check on such things.

Decades ago, I first saw La petite Lise in a 35mm print on an editing table at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). I finally saw it on the big screen in 2015, when our UW Cinematheque ran a few Grémillon films in 35mm. Then-graduate student Jonah Horwitz provided the program notes.

Grémillon is best known outside France for the trio of films he made during World War II: Remorques (1941), Lumière d’été (1943), and La ciel est à vous (1944). Criterion has released a box set of all three as Jean Grémillon During the Occupation. Some of his other films are available on disc, as a search of the director’s name on Amazon.com or amazon.fr reveals (including some with English subtitles).

The simple plot involves Berthier, who is serving a long sentence in a prison in Cayenne for having killed his wife in a fit of jealousy. Heroic behavior on his part during a recent fire has led to an early release, and he expresses his desire to see his daughter, Lise, now grown up. All this sets us up to be sympathetic toward him, despite the fact that he is played by by Pierre Alcover, a large, rather sinister looking actor. (Best known to modern audiences, I suppose, as the corrupt banker in L’Herbier’s L’Argent.) Unbeknown to him, Lise has been working as a prostitute but has now ended that in anticipation of marrying André. The pair are in desperate need of obtaining 3,000 F within 48 hours to buy a small house.

Berthier’s reunion with Lise is joyful, and he manages to find a job with his old boss, who gives him a generous advance on his salary. Knowing nothing of this, Lise and André visit a Jewish pawnbroker who André believes has cheated him in the past. When he threatens the pawnbroker, a fight breaks out, and Lise accidentally kills the man. Berthier learns of her past and of the killing, and his great love for her leads him to turn himself in as the killer.

The story is quite touching, in large part because Alcover and Nadia Sibirskaïa (who played the younger girl in Menilmontant) convey the deep love between the pair.

Grémillon adds some unconventional touches which have little direct relation to the plot and are largely dependent on sound. These give the simple plot some variety.

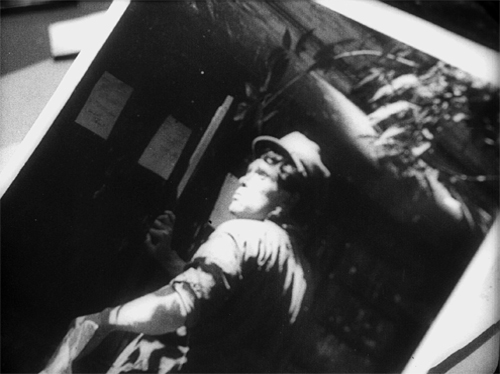

The opening, for example, takes place in the Cayenne prison, with Berthier learning of his pardon from the warden. In the crowded dorm, he reveals to two fellow convicts that his good fortune makes it impossible for him to participate in a planned escape. He shows them a photograph of Lise as a child. Most of the extended dorm scene, however, consists of fairly tight shots of other men’s activities, all packed into the crowded room. The soundtrack, rather than catching scraps of dialogue, remains a loud babble of many men talking at once. These shots tell us us next to nothing about the narrative, beyond suggesting the grim conditions to which Berthier faces returning to at the end. It does, however, create an effective atmosphere of the prison as a backdrop to occasional shots of Berthier gazing at the photo of Lise.

Another example is a scene late in the film, when, having learned of the killing, Berthier goes looking for André. He tries to enter a nightclub, but it is too crowded. He stands watching with several others through the window as a Black dancer performs a lively number for a mixed Black and white audience. For a brief interval, the scene becomes a musical number, extending to the point where couples start dancing, with Berthier becoming quite peripheral to the action. The performer and dancers add nothing to the story, but the scene is delightful in itself.

These and other moments draw us away from the linear progression of the story and make La petite Lise one of those small, simple films that transcend their apparently modest nature–like those of Jean Epstein and Dimitri Kirsanoff.

La petite Lise remains difficult to see. It has never, as far as I know, been available on home video. Grémillon’s film is not on YouTube, but there are several clips from key scenes. (All are pretty poor in quality, and I haven’t seen a good print of it. If elements survive in archive, it seems a major candidate for restoration.) An excerpt from the scene in the prisoners’ dorm near the beginning gives a good sense of the babble of voices. The Black dancer’s number as Berthier searches for André is shown nearly in its entirety. Both of these were put up at the time of the Cinematheque screening in Madison. There are some other brief scenes: the visit to the pawnbroker leading up to the murder, the scene of Berthier applying to his former boss for a job (which includes a sound bridge from the previous scene of Lise at home), and the scene in a restaurant which Lise and André visit in the hope of establishing an alibi. Otherwise, keep an eye open for it if you live near at archive that has public screenings.

For a look at Ford’s flashy style in his earliest features, see here. For a defense of How Green Was My Valley‘s Oscar win over Citizen Kane for best picture, see here.

My video essay, “Mastering a New Medium: Sound in M“ is number 11 in the series “Observations on Film Art” on The Criterion Channel.

La Chienne (1931)

Rotterdam starts strong

Dear Comrades! (2020)

DB here:

Thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, we’re able to visit this venerable event, celebrating its fiftieth year! As with Venice and Vancouver, we’re happy to get online access to some outstanding films. We pass along the news to you here and in upcoming entries.

A dish best served cold?

Riders of Justice (2020).

Why is revenge so common as a driving force in film, fiction, and drama? Well, it sets up story action we like: search, mysteries, discovery, pursuit, confrontation. And it’s an impulse we find easy to understand. If you wrong me or mine, I’m likely to want payback.

As a high-school teacher once said to me, when I protested that the punishment wasn’t fair: “I don’t want to be fair. I want to be just.” In real life, Trump whines about unfairness, but he wouldn’t recognize justice if it met him head-on. Which it just might. Anyhow, in movies justice becomes our noblest excuse for the pleasures of vengeance.

Once our sympathy for the avenger is aroused, the storyteller has to decide how to treat the plot. Revenge shouldn’t be easy. It comes with a price. In Hong Kong films, revenge is usually the righteous settling of accounts.The price it demands is usually physical (wounds, maybe death) and social (the loss of friends cut down in the assault).

There’s another tradition of revenge drama that emphasizes the moral costs of revenge, the sense that it taints the avenger. You turn implacable, self-righteous, prone to error. Maybe the target isn’t really guilty? And can’t you forgive? And aren’t you turning obsessive? Can you sacrifice the other parts of your life to this mission? All of these questions haunt Anders Thomas Jensen’s seriocomic thriller Riders of Justice.

Markus, a stolid soldier, returns home when his wife is killed in a subway accident. His daughter Mathilde is traumatized. Markus’s stoic grief changes to rage when he is told by the statistician Otto, who survived the accident, that the crash was engineered by a gangster killing a rival. Markus’s icy pledge to vengeance sweeps up Otto, his two hacker friends, Mathilde, her boyfriend, and others.

In early days of this blog I wrote a lot about Danish films, which I’ve always admired. Many years ago Anders Thomas Jensen, director of Riders of Destiny, brought to our Wisconsin Film Festival The Green Butchers (2003). His scripts, for his own films and those directed by others, find a unique, tightly designed blend of drama and humor, with a penchant for showing the dumb side of male bonding (In China They Eat Dogs, 1999; Flickering Lights, 2000; Adam’s Apples, 2005)

Riders of Justice is in this vein, but it plays with larger ideas too. It starts and ends with a network-narrative premise (again, very Danish) emphasizing remote human connections. In between the characters come to grips with the role of chance in their lives. Scenes both serious and comic show them trying to reckon the reason behind their impulses. Even the numbermumbler Otto, who calculates probabilities of everything, admits to Mathilde that even the simplest event is impossible to explain through cause and effect.

You know that comfortable feeling you get at the start of a movie, when the story has hooked you, the characters command your sympathy (even when they make mistakes), and you realize that you’re in good hands for the next couple of hours? That was my response to Riders of Justice. Not least, it brings together for the umpteenth time two of the finest actors in world cinema, Mads Mikkelson (scary, in a trim Pentateuch beard) and Nikolaj Lie Kaas (sensitive, blinking behind wire-rims).

Riders of Justice has been purchased by Magnolia and is planned for a spring release.

Bolshevik nostalgia in 1.33

Dear Comrades! (2020)

“Dear Comrades!” is the salutation of a letter never sent. At a meeting of officials trying to handle a sudden strike, Lyudmila Syomina voiced a need for harsh reprisals for these traitors to the Soviet state. But after being called to write a letter and read it at a forum, she flees. She is torn by fear that her daughter has been captured or killed during the very violence she advocated.

Dear Comrades!, the latest and perhaps best film from the distinguished, pleasantly erratic director Andrei Konchalovsky, is set in Novocherkassk, 1962. The strike and the massacre were revealed in 1975 by Alexandr Solzhenitsyn and confirmed by an inquiry in 1992. Konchalovsky has undertaken a historical recreation, an examination of his parents’ postwar generation, and, I think, an oblique critique of authoritarianism. He seems equivocal about Putin’s “managed democracy” (though he’s not as big a booster as his brother Nikita Mikhalkov). In any case, we can’t help seeing the film as echoing the tyranny on display in Russia’s recent years, i.e., yesterday. Unlike the current demonstrators supporting Navalny, though, Konchalovsky’s characters yearn for well-run autocracy. After all, under Stalin, prices went down.

Classic Soviet fiction and film featured what’s come to be called a “conversion narrative.” In order to build any plot, you need drama. But you also have to conform to Bolshevik ideology. Some conflict can be supplied by villains (“traitors,” “wreckers”) seeking to undermine the Great Soviet Experiment. You can also create drama with characters who are ignorant of the true way, or uncertain about abandoning personal commitments and embracing the Party. So the plot can trace the gradual conversion of a character to sturdy Communist principles. This functions, in classic Socialist Realist storytelling, as psychology.

But Lyudmila is a hard-core Party loyalist. She benefits from the perks of office: a love affair with her superior in a nice apartment, the ability to jump the queue scrambling for food and matches, a paycheck that pays for a European-style coiffure. In exchange she mouths, with unblinking cobra severity, a strict adherence to policy. Yet her daughter Svetka has joined the strike and goes missing during the melée.Lyudmila’s search doesn’t easily dissolve her ideological tenacity. Like Mother Courage, Lyudmila stubbornly refuses to see what’s in front of her. She can’t believe that the KGB, not the Army, would plan a massacre that mowed down citizens.

Eventually we get glimpses of a de-conversion narrative. Lyudmila starts to sense that the current system is corrupt. “What am I supposed to believe in if not communism? Blow it all up and start again.” Yet what should replace it? The only alternative she knows. “I wish Stalin would come back.”

Konchalovsky has shot the film in lustrous, drypoint black and white, and in a silent-era ratio of 1.33:1. It’s one of the most elegantly composed and staged films I’ve seen in recent years; it could be studied just for its use of axial cuts. I’d almost call it “Straubian-Huilletian,” were it not so defiantly committed to the melodrama of a family crisis within social turmoil. But Dear Comrades! is far from your standard historical pageant. It’s at once austere and inventive.

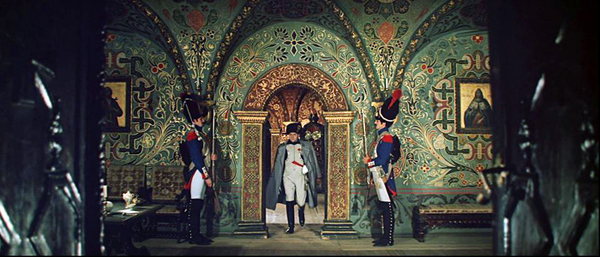

Konchalovsky activates a great many motifs from classic Soviet film, treating them both for sly comedy and sharp drama. Satire on bureaucracy, another traditional source of plot developments, pervades the first half. Like Eisenstein in October, Konchalovsky can spare a shot mocking an empty conference table after the staff has fled.

Eisenstein is of course more grotesque: the panicked Mensheviks have leaped out of their furs, or been Raptured. The portrait of Khrushchev stands in for the Stalin picture hanging in every Socialist Realist office, parlor, bivouac, and meeting hall.

Konchalovsky stages the massacre of the strikers mostly through the heroine’s viewpoint. In place of the vast views supplied by Eisenstein in October (1928), the camera is tied down to a beauty shop.

In Soviet World War II films, the officials plan strategy in monumental headquarters (Front, 1943). The shabby offices of Konchalovsky’s provincials seem both cramped and hollow.

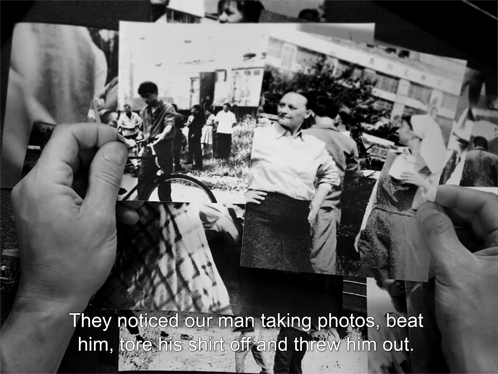

During the agitation and cleanup, Konchalovsky seems to me to rework specific images from Eisenstein’s Strike (1925). The hosing of blood from the streets seen in reflection echoes a shot of the factory in Strike. And in both, the police study the spies’ snapshots of strikers.

Dear Comrades! deserves all the attention it’s getting. Winner of this year’s Special Jury Prize at Venice, it has been picked up by Neon for US release. It’s also Russia’s submission for the Best International Feature Film Academy Award. It’s being streamed by several film festivals, notably Seattle’s, which offers it at a very reasonable price. But how I long to see it on the big screen.

I discuss some Danish network narratives in Chapter 7 of Poetics of Cinema and other examples in some entries. Katerina Clark has an excellent discussion of the conversion narrative in The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Indiana University Press, 2000). For a discussion of Socialist Realist film style, see this entry.

P.S. 4 Feburary 2021: Anders Thomas Jensen gives a very informative interview about Riders of Justice in Variety.

Riders of Justice (2020).

Quality bingeing

Mon Oncle (1958)

Kristin here:

Or binging, if you prefer. Either is an acceptable spelling.

Streaming entertainment is one of the things that are saving our sanity as we sit in our homes. With the theaters closed and new movies either delayed or sent straight to streaming, movie critics, other journalists, and movie buffs are now making best-films-to-stream-during-the-pandemic lists a new and common genre across the internet.

Maybe you’ve been streaming a lot of TV series, even ones you’ve already seen, and are feeling a bit guilty about that. Maybe you’re longing for something more worthwhile to watch but wishing that that something would take up more time than your average feature film.

For those people, I offer a list of films to binge. These are either long in themselves or are split up into many parts that can be binged just like TV series. Others are stand-alones but can be grouped in meaningful ways.

My experience is that online disc orders are taking longer than usual. With Amazon prioritizing health and work-at-home supplies, Blu-rays are taking around two weeks rather than two days. (David and I, of course, count Blu-rays and streaming as part of our work-at-home requirements.) While you’re waiting, I’ll bet many of you have some of these discs on your shelves already and have always meant to make time for them. That time, lots of it, has arrived.

Serials

Many fine serials were made in the silent era, but Louis Feuillade remains the director that most of us think of first in relation to this format. His three great serials of the 1910s (not including, alas, the fine Tih Minh [1918]) are available on home video.

Fantômas (1912). 5 episodes, 337 minutes. Fantômas is available in Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. David wrote a viewer’s guide to it here.

Les Vampires (1915). 10 episodes, 417 minutes. Les Vampires is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Kino Lorber. As far as I can tell, it is streaming only on Kanopy (apart from unwatchable public domain pre-restoration prints).

Judex (1917). 12 episodes, 315 minutes. Judex is ordinarily available from Flicker Alley, though it is currently listed as out of stock. Amazon has 5 left. For maximum bingeing opportunities, watch all three serials in a row and then stretch them out with Georges Franju’s charming remake, Judex (1963) for an extra 98 minutes (it’s $2.99 to stream it on Amazon Prime).

Miss Mend (Boris Barnet, 1926). Three episodes, 235 minutes. The only American-style serial from the Soviet Union that I know of, or at least the only one easily available. I wrote about it briefly when it first came out from Flicker Alley. You can still get it from Flicker Alley or Amazon. We wrote briefly about it here.

Le Maison de mystère (Alexandre Volkoff, 1923). 10 episodes, 383 minutes. I’ve already written in some detail about this long-lost serial. It’s probably not as good as Feuillade’s best, but it’s good fun and beautifully photographed (see top of section) and acted–and long enough to require a meal break. Fans of the great Ivan Mosjoukine (as he spelled his name after emigrating from Russia to France) will especially want to see this one. Available from Flicker Alley

Berlin Alexanderplatz (Rainer Werner Fassbender, 1980) 13 episodes and an epilogue. 15 hours, 31 minutes. Back when it first came out, this was treated more as a film than a TV series. It showed in 16mm at arthouses and archives. David and I drove to Chicago to see the whole thing in batches over a single weekend at The Film Center (now the Gene Siskel Film Center). It’s available on either DVD or Blu-ray as a Criterion Collection set (#411 for you Criterion number-lovers). It’s also streaming on the Channel. Both have a batch of supplements, even the 1931 German film of the novel, so you can stretch the experience out even longer.

Silent serials may work for some families, if the kids have been introduced to silents already through the more obvious route of films with Buster Keaton, Charlie Chaplin, and the other great comics of the era. If not, families can fill their time with more recent films in episodes with continuing stories.

The serial format has had a comeback in recent decades, partly due to the influence of the first Star Wars trilogy and partly to the need for ever expanding amounts of moving-image content in the era of home-video, cable, and internet services. For those who want to binge Star Wars, you don’t need my guidance. Anyway, I gave up after the first of the recent series, the one where Adam Driver took over as the villain. (Not that I have anything against Adam Driver. It was the film.) Even daily life in a pandemic is too short for more.

The Harry Potter series. (2001-2011) Eight episodes, 990 minutes, or 16.5 hours. This series is not high art, but it’s pretty good, highly entertaining (to some, at least), and even has one episode, number three, directed by Alfonso Cuarón, HP and the Prisoner of Askaban (above). The others are HP and the Sorcerer’s Stone (or Philosopher’s Stone in the UK and elsewhere; Chris Columbus), HP and the Chamber of Secrets (Chris Columbus), HP and the Goblet of Fire (Mike Newell), HP and the Order of the Phoenix, HP and the Half-Blood Prince, HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part I, and HP and the Deathly Hallows: Part II (the last four, David Yates). These films are, of course, available in multiple versions, on disc and streaming. As far as I can tell, none of the complete boxed sets have the two last parts in 3D; those have to be purchased separately. Having seen the last film in a theater in 3D, I can say that it doesn’t seem to be one of those films that is much improved if one sees it that way (unlike Mad Max: Fury Road, in the section below).

The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings extended editions: An Unexpected Journey (2012), The Desolation of Smaug (2013), The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), The Two Towers (2002), and The Return of the King (2003, above). 6 episodes, 1218 minutes, or 20 hours, 18 min. Yes, for sheer length this serial tops them all. Plus there are lots of supplements. Each part of the Hobbit films has one commentary track and a bunch of making-ofs, adding up to 40 hours, 5 1/2 minutes. This pales, however, in comparison with the LOTR extended editions, which have four commentary tracks, totaling 45 hours, 44 minutes. The making-ofs are hard to get exact figures for, but I estimate about 22 hours for all three films. That’s about 68 hours of audio and visual supplements.

To top that off, the Blu-ray set contains the three feature-length documentaries by Costa Botes: The Fellowship of the Rings: Behind the Scenes, The Two Towers: Behind the Scenes, and The Return of the King: Behind the Scenes, all adding another 5 hours, 2 1/2 minutes. (Botes’s films were also included in a “Limited Edition” reissue of the theatrical versions of the LOTR films in 2006.) In toto, if one watches every single item and listens to all the commentaries, one could escape 133 hours and 10 minutes of isolation boredom–and possibly go mad in the process. But treating the bingeing as an eight-hour-a-day job, it would come to 16 1/2 days.

All this does not include the supplements accompanying the theatrical-version discs. These are charming but more oriented toward introducing complete neophytes to the universe of Middle-earth than toward giving filmmaking information.

Series

Series, as opposed to serials, usually involve continuing characters but self-contained stories. Most of the series below could be watched out of order without suffering much. It would help to watch Mad Max first, since it’s an origin story. The Apu Trilogy should be watched in order because it’s about the central character’s stages of life. Each of the M. Hulot films bears the traces of the contemporary culture in which it is set, but one can understand each fine out of order. I saw Traffic first, in first run, and then saw the others.

Mad Max (1979), Mad Max 2, aka The Road Warrior (1981), Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome (1985), and Mad Max: Fury Road (2015) add up to 411 minutes, or 6 hours and 51 minutes. You know them, you love them–but have you ever watched them straight through? We’ve written about Fury Road (here and here). That’s a film where the 3D really does play an active role.

Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot films: Mr. Hulot’s Holiday (1953), Mon Oncle (1958, see top), Play Time (1967), and Traffic (1971). They add up to 7 hours and 4 minutes. Or add his non-Hulot films, Jour de fête (1949) and Parade (1974) for just under an additional 3 hours of hilarity. You can buy all of Tati’s films at The Criterion Collection or stream them at The Criterion Channel. Throw in my “Observations on Film Art” segment on Parade for an extra 12 minutes. And check out Malcolm Turvey’s new book, Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism, soon to be discussed in a portmanteau books blog here.

Dr. Mabuse films plus Spione: Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (1922), Spione (1928, frame above), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933) and The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse (1960), adding up to 610 minutes, or 6 hours and 10 minutes. Few if any directors have extended a series over such a stretch of time, and the Mabuse films are quite different from each other (including having different actors play the master criminal). I throw Spione into the mix because the premise and tone are so similar to the first Mabuse film. Haghi is basically Mabuse as a master spy instead of a gambler and general creator of chaos; given that he’s played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge, who was the first Mabuse, the comparison is almost inevitable. One can almost imagine Haghi as just another of Mabuse’s disguises and it fits right into the series. I’ve linked the streaming sources to the titles above.

Kino Lorber has the restored version of Der Spieler on DVD and Blu-ray, Eureka has the restored version of Spione on DVD and Blu-ray (note: Region 2 coding) The Criterion Collection offers a DVD of Testament, and Sinister Cinema has a DVD of The 1,000 Eyes. (For those who want to dig deeper, there a Blu-ray set of all of Lang’s silents, from Kino Classics and based on the F. W. Murnau Stiftung restorations. That totals 1894 minutes, or about 31 and a half hours. I don’t know if that counts the supplements, but there are lots of them.)

Apu Trilogy: Pather Panchali (“Song of the Little Road,” but nobody calls it that, 1955), Aparajito (1956), and The World of Apu (1959). 341 minutes. Satyajit Ray’s trilogy may seem like a serial, in that it follows the life of the main character, Apu. Yet Ray had not planned a sequel until Pather Panchali achieved international success, and the films have big time gaps in between, with no dangling causes. These are three of the most beautiful, touching films ever made, and the stunning restoration from a damaged negative and other materials is little short of a miracle. If you have never seen these or saw them before the restoration, do yourself a favor and binge them. Have some tissues handy, and I don’t mean for stifling coughs and sneezes. Available on disc from The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Collection here, here, and here.

Now I briefly cede the keyboard to David for his recommendations of Hong Kong series.

Triads vs. cops, Triads vs. Triads

Infernal Affairs (2003).

There are many delightful Hong Kong series. I enjoy the silly Aces Go Places franchise (1982-1989) and the pulse-pounding Once Upon a Time in China saga (1991-1997). Alas, almost none of these installments entries are represented on streaming. I could find only the weakest OUATIC title, Once Upon a Time in China and America (1997) on Amazon Prime, Vudu, and iTunes.

If you want to go for samples, there are two diversions from the ever-lively Fong Sai-yuk series. The Legend (US title of the first entry, a bit pricy from Prime). The more reasonably priced Legend II, the US version of the second entry, has a fantastically funny martial-arts climax featuring Josephine Siao Fong-fong as Jet Li’s mom. This is available from several streamers. Older kids won’t find either one too rough, I think.

There are two outstanding series more suitable for adult bingeing. Infernal Affairs (2003-2004) was made famous by Scorsese’s remake The Departed (2006), but the original is better, and the follow-ups are loopier. The first entry offers solid, suspenseful plotting and meticulous performances by top HK stars Tony Leung Chui-wai and Andy Lau Tak-wah, supported by a rogues’ gallery of unforgettable character actors. Parts two and three spin off variations on the first one, tracing out before-and-after incidents and throwing in some quite strange narrative contortions. The whole thing provides an engrossing five and a half hours of entertainment. Available from several services.

In my book Planet Hong Kong I analyze the trilogy as an example of how directors Andrew Lau and Alan Mak Siu-fai created a more subdued thriller than is usual in their tradition. Bonus material: In the spirit of providing free stuff during the crisis, here in downloadable pdf form is my little chapter on the trilogy: Infernal Affairs interlude.

Also subdued, even subtle, is Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Election (2005) and Election 2 (aka Triad Election, 2006). These films dared to show secret gang rituals that other filmmakers shied away from. The first part plays out ruthless competition among rival Triad leaders, including strikingly unusual methods of punishing one’s adversary. The second entry, even more audacious, suggests that Hong Kong Triad power is intimately tied up with mainland Chinese gangs, backed up by political authority.

Johnnie To’s pictorialism, so feverish in The Longest Nite (1998), A Hero Never Dies (1998), The Mission (1999), and other films, gets a nice workout here as well. Infernal Affairs is agreeably moody, but the Election films are black, black noir.

The pair add up to three hours and a quarter. The first film is apparently available only on disc but the second is streaming from several sources.

Of course, to get into the real Hong Kong at-home experience, some viewers will find all these films easily and cost-free on the Darknet.

Thematic combos

Flicker Alley’s Albatros films. 5 films, 664 minutes, or 11 hours and 4 minutes. I wrote about the DVD set, “French Masterworks: Russian Émigrés in Paris 1923-1929” when it first came out. It’s still available here. The Albatros company made some of the key films of the 1920s, most of which are still too little known, including Ivan Mosjoukine’s Le brasier ardent (1923, above). If this is still a gap in your viewing of French films, here’s a chance to fill it.

Yasujiro Ozu: The Criterion Collection has released a helpful thematic grouping of some of Ozu’s early films. One is “The Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies” (DVD and streaming), including I Was Born, but …, Tokyo Chorus, and Passing Fancy, adding up to 281 minutes. The British Film Institute has gone further along the same lines, releasing “The Gangster Films,” also three silents: Walk Cheerfully (1930), That Night’s Wife (1930), and the wonderful Dragnet Girl (1933); they add up to 259 minutes. The BFI has also put out “The Student Films,” (listed as out of stock at the moment) yet more silents: Ozu’s earliest complete surviving film, Days of Youth (1929), I Flunked, But … (1930), The Lady and the Beard (1931) , and Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth? (1932), adding up to 251 minutes.

David has recorded an entry on Ozu’s Passing Fancy for our sister series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel; it should go online there sometime this year.

Or watch all the “season” films in a row: Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951), Early Spring ((1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Late Autumn (1960), End of Summer (1961), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962), for a grand total of 840, or 14 hours. Including An Autumn Afternoon is cheating a bit, since the original title means “The Taste of Mackerel.” Still, it’s so much like the earlier films in equating a season with a stage of life that the English title seems perfect. The early films equate the seasons with the young people, about to marry or recently married, while in the later films, and especially the last three, the seasons refer to the older generation, lending an elegiac tone to the end of Ozu’s career. David has done commentary for the DVD of An Autumn Afternoon.

All of these (except for Days of Youth) and many other Ozu films can be streamed on The Criterion Channel, which also has a bunch of supplements on this master director.

Or just watch The Criterion Channel’s Kurosawa films in chronological order, or Bresson’s or Godard’s or Bergman’s or …

Or watch all of Hideo Miyazaki’s films in chronological order, with or without the company of kids.

Just really long films

War and Peace (Sergei Bondarchuk, 1965-1967, above) 4 parts: 7 hours, 3 minutes, 44 seconds. I suppose this is technically a serial, since the parts were released over three years. Still, the idea presumably was that it ultimately should be seen as one film, and the running time would permit it being seen in one day fairly easily. I have not seen this restored version, only the considerably cut-down American release back when it first came out. I remember it as being quite conventional, but on a huge scale in terms of design, cinematography, and crowds of extras. Seeing it in its original version would no doubt be impressive (see above). Available on disc at The Criterion Collection and streaming on The Criterion Channel. The supplements total 175 minutes and four seconds, pushing the total up to nearly 10 hours.

Satan’s Tango (Béla Tarr, 1994) 450 minutes, or 7 hours 30 minutes. Film at Lincoln Center has just made Tarr’s epic available for streaming; you can rent it for 72 hours and support a fine institution. As to owning it, the DVDs seem to be out of print. There is, however, a Blu-ray coming from Curzon Artificial Eye on April 27 in the UK. Pre-order it here. Obviously many of us will still be stuck inside by the time it arrives. Or if you have it on the shelf and never quite got around to watching it, here’s your chance. Derek Elley’s Variety review sums up its pleasures. Our local Cinematheque has shown it twice, once in 35mm and more recently on DCP (see here, with the news buried at the bottom of the story). David reported on that first showing, and later he wrote a general entry about Tarr’s work on the occasion of having met the man himself.

Shoah (Claude Lanzmann, 1985) 550 minutes, or 9 hours and 10 minutes. The Holocaust examined through modern interviews with a broad range of people involved. Available in a restored version on disc from The Criterion Collection. It does not seem to be available currently for streaming.

Unclassifiable

Then there’s Dau (2020-), a biopic of a Soviet scientist that is perhaps the most ambitious filmmaking venture ever.

Shot on 35mm over three years in a real working town with 400 characters played by actors who remained in character and costume round the clock the whole time. Few have seen these, though two showed at the Berlin festival this year. We haven’t seen them but plan to give it a go, since they have just shown up online. Here’s a helpful summary of the project. At the Dau Cinema website, you can stream the first two films for $3 each: Dau. Natasha (2:17:53) and Dau. Degeneration, (6:09:06) adding up to 8 hours and 27 minutes. Twelve more films are announced for future release, with no timings given. Clearly not suitable for family viewing.

I have not attempted to add up all these timings, but if you can track most of them down, they might get you through much of the isolation period. Stay safe!

Election (2005).

Flicker Alley fills the Pudovkin gap

The End of St. Petersburg (1927)

Kristin here:

Flicker Alley continues its editions of classic silent films previously unavailable on disc or available only in inferior copies. Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features, Mother (1926), The End of St. Petersburg (1927), and The Heir of Genghis Khan (commonly known in English as Storm over Asia, 1928), are packaged here as “The Bolshevik Trilogy.” (As of now, the discounted price at Flicker Alley’s own site is considerably cheaper than what Amazon is charging.) All three films have appeared in my annual survey of the ten best films of ninety years ago; see the entries for 1926, 1927, and 1928.

The only restoration in the set is Storm over Asia, done in connection with Lobster Film in Paris.

Mother

Pudovkin’s trilogy is a sort of survey of key events in Russia’s move toward becoming the Soviet Union. Mother, based on Maxim Gorki’s novel of the same name, deals with the failed Revolution of 1905. That revolt was viewed as an important precursor to the Communist Revolution of 1917. Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin (1925) was an anniversary film for the same struggle.

Pudovkin is known for centering his films around individual protagonists rather than the group protagonists favored by Eisenstein in his first three silent features. Here the hero is Pavel, a young worker and clandestine revolutionary who lives with his drunken father and downtrodden mother. When guns that Pavel has hidden in the house are discovered, the mother naively betrays her son to the police. He is imprisoned. After a prison break, Pavel joins a protest march, and his mother, now converted to the rebellion, sees him mowed down but carries the flag onward.

Pudovkin’s style is already fully formed here. It’s very flashy, employing the usual fast cutting and depending on highly unconventional ways of framing shots. Pavel’s escape from prison, for example, contains a bird’s eye view as he climbs down some railings to help his comrade put a guard out of commission (above) and a shot during Pavel’s trial uses one of the director’s favorite compositions, shots of police or soldiers seen past their horses heads.

Pudovkin also tends to use imagery of nature to symbolize the revolutionary impulse, as in the famous breaking up of ice on a river during the prison break and protest march. Rivers and lonely trees against low horizons appear in all three films, and the escape over ice floes returns in Storm over Asia (see bottom image). Such techniques perhaps help explain why Pudovkin was the most popular of the major Montage directors.

Given the importance of having these three films available, I hate to find fault. This print of Mother is simply the old Blackhawk/Image. It’s certainly acceptable, but a restoration of Mother, and as we shall see below, The End of St. Petersburg remains to be done. That better prints exist is shown by the illustrations I used in the 1926 entry linked above, which were taken from a 35mm archival copy.

The End of St. Petersburg

For many film fans, The End of St. Petersburg is perhaps the least emotionally involving of these three films. Pavel in Mother and the unnamed Mongolian hunter in Storm over Asia are appealing characters, friendly, brave, and ready to stand up to imperialists, soldiers, and police–and both the victims of flagrant injustices. The unnamed peasant who is at the center of The End of St. Petersburg is initially an ignorant, selfish young man. In a time of famine shortly before World War I, he goes to the city in search of work and becomes a scab, working at a large factory during a strike.

The peasant is friends with one of the workers who fomented the strike, and, echoing the actions of the mother in the earlier film, naively betrays the man to the management of the factory. Once the war breaks out, the peasant stolidly suffers through the entire conflict at the front. Only late in the film does he realize his folly and join the Bolsheviks in the 1917 attack on the Winter Palace. This ends the period when the city was named St. Petersburg.

The peasant is also not in the film nearly as much as the central characters of the two other films. Instead of a compact dramatic narrative, Pudovkin takes us from an era in which the stock market rules society through the war–also waged for the benefit of capitalists–to the Winter Palace attack of October, 1917. The peasant weaves through this, but there is no real point-of-view figure.

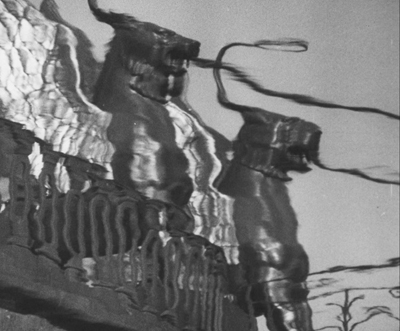

The End of St. Petersburg is a marvelous film nonetheless. In his survey of revolutionary progress, Pudovkin’s flashy style is even more self-assured. In a sense, the city becomes the central symbolic source, with the statues for which St. Petersburg (as it is now again known) is famous representing the power against which the Bolsheviks revolt. The opening scene includes a remarkable series of shots, not of the famous landmarks, but of their reflections in the city’s canals, filmed and then shown upside down, as if the city is shimmering with the weakness that will soon bring down its rulers. The image above shows the griffins holding the cables for the well-known suspension pedestrian bridge, the Bank Bridge.

There are fascinating parallels to Eisenstein’s October, which came out a year later. Both films were among three made to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Revolution. The End of St. Petersburg and Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October were finished and released in the anniversary year, but Eisenstein’s was not. Pudovkin and Eisenstein shared a fascination for the rich Tsarist trappings of the Winter Palace, which were, according to them, enjoyed by the short-lived Provisional Government and its supporters. Certainly The End of St. Petersburg contains some beautifully composed and lit shots of decadent luxuries surprisingly similar to those Eisenstein filmed. (See top.)

The print shares the cropping problems that I pointed out in my 1927 post including The End of St. Petersburg. Since this version is, like earlier releases, based on a 1960s Gosfilmofond “restoration” that sliced off the left of the frame to make room for a recorded soundtrack, all of the shots are too square. I was frequently aware that the frame was simply too close, eliminating part of the image. (The lady in the image at the top was originally more centered in the composition.)

As if to compensate for this problem, the visual quality of this print is startlingly good, as the images immediately above and at the top show. The clarity of the images is actually better than that of the restoration of Storm over Asia. I cannot resist showing another example. Here, in the final attack on the Winter Palace, there is an amazing precision of the lighting in picking out each member of the group of soldiers waiting for the signal to launch the offensive.

We still need a restoration of this film with the full width of the original. In the meantime, however, this version is a substantial improvement over earlier video releases.

Storm over Asia

Pudovkin completed his survey of the creation of the revolutionary struggle with an unusual choice: to set his story in one of the countries that would become close allies of the USSR. It takes place in the early 1920s in Mongolia, where White Russian forces were battling the Chinese for domination. The Bolsheviks formed an army in Mongolia and ultimately helped the country win its freedom. (Pudovkin distorts history by making the imperialist government British.)

The Mongolian hunter is played by Valerii Inkhizinov, a Mongolian citizen who had studied under Lev Kuleshov alongside Pudovkin. His character is cheated by British agents who cheat him out of the fair price for a rare, valuable fox fur (above). His retaliatory attack makes him a fugitive, and he joins a partisan group of Bolsheviks in the mountains simply in order to survive. He is eventually arrested and shot, but a document he carries seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. Nursing him back to health, the British officials exploit this connection to their own advantage. Ultimately he rebels. A final fantasy sequence has him leading at attack by partisans as a huge tempest symbolically sweeps away the British army

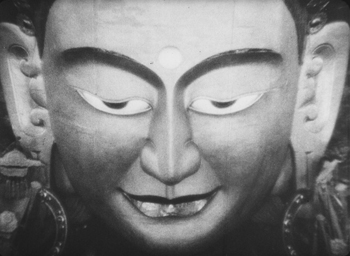

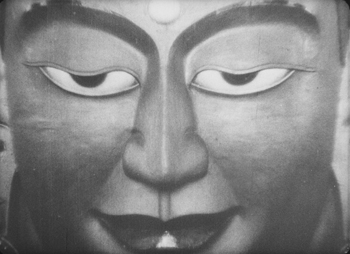

There are virtuoso passages of editing. One comes when he rebels against being cheated over the price of his rare fox fur. Another comes at the end, during the symbolic tempest. In between, Pudovkin often follows a convention of Montage filmmaking, breaking scenes into multiple shots. When a British official and his wife visit a local temple, Pudovkin strings together five increasingly close views of the face of a large statue.

Although the three films have no overlapping characters or social situations, they play very well as a trilogy.

This Blu-ray pair of discs is not a perfect restoration of the three films, but it is so much better than what was available before that this becomes a vital addition to any collection that purports to covers the basic historical classics of the silent cinema.

The set includes several informative extras, including a booklet essay by Amy Sargeant, author of two books on Pudovkin, and two commentaries by present and past curators at George Eastman House: Peter Bagrov on Mother and Jan-Christopher Horak on Storm over Asia. Some short videos analyzing Pudovkin’s editing and showing 1920s footage of St. Petersburg are also included.

Our friend and colleague Vance Kepley authored an in-depth book-length study, The End of St. Petersburg (I. B. Tauris, 2003).

Storm over Asia (1928)