Archive for the 'National cinemas: Russia and USSR' Category

The ten best films of … 1924

Die Nibelungen: Siegfried

Kristin here:

For a seventh year running, we skip ranking the current year’s films and instead hark back 90 years.

We started out with a list that was essentially an appendix to an entry, but soon we were dedicating whole entries just to the list. Our entries for past years are here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, and 1923.

These lists are our way of calling attention to important silent films that some readers may have overlooked. In one case here we point out a largely forgotten film that deserves to be better known, in the hope that an archive will take the hint. With the proliferation of silent-film festivals, of DVD and Blu-ray releases with restored prints and supplemental material, and of TCM’s eclectic screenings of foreign and silent titles, there seems to be considerably more interest in these early classics. Herewith our choices for 1924.

For the last few years I’ve struggled to fill out the full list of ten films with truly deserving items. But as I’ve been predicting, the 1924 choices fell easily into place. As usual, some of these are obvious picks, already famous to most readers. Others are less obvious, and a few are unknown except to specialists. Some, though very important historically and artistically, are not currently available on DVD, which is a real shame.

At last, the USSR

Films in the Soviet Montage style make up one of the most important cinema movements of all times. The key filmmakers of the movement, Eisenstein, Pukovkin, Dovzhenko, Kuleshov, Kozintzev and Trauberg, and others began their work later than the German Expressionist and French Impressionist directors. But at last one joins our list, with Lev Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks.

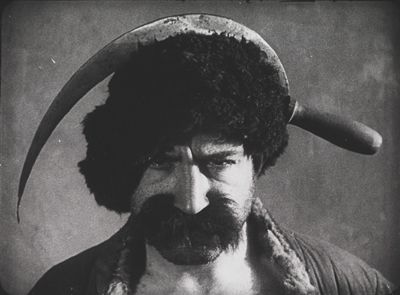

Although Kuleshov’s work has become more widely available, his most familiar work is still By the Law (1926), a grim tale of two members of a gold-prospecting team agonizing over how to bring to justice a colleague who has committed a terrible crime. Mr. West couldn’t be more different. This hilarious and grotesque comedy satirizes American perceptions of the new Soviet Union, as Mr. West, president of the YMCA, comes to for a visit, his faithful cowboy friend Jeddie in tow. They’re terrified of the barbaric land they expect to encounter, and a gang of thieves dupe Mr. West by dressing up in outfits that caricature West’s images of Bolsheviks (above).

In making the film, Kuleshov and his team drew upon the experiments they had been doing in his classes he ran of the early 1920s. Film stock was scarce and all he and his students could do was practice staging scenes and make short editing experiments. They explored the possibilities of “biomechanical acting,” a style based more on gymnastic control and energy than on psychological subtleties of facial expression.

Once the group did get the resources to make a feature, their delight is evident in the lively editing and the exuberant performances. Alexandra Khokhlova, a gangly woman who was married to Kuleshov and starred in most of his films, plays a vamp who tries to lure Mr. West into her toils. Pudovkin, who studied with Kuleshov before going into directing himself, is the well-dressed gang leader who pretends to guide Mr. West away from danger. Boris Barnet, also to become a major director, performs feats of derring-do as Jeddie tries to save Mr. West.

Mr. West is not only a satire on Western fears of post-Revolutionary Russia but also a parody of American serials. (The latter was something Barnet soon tried in an actual serial, his 1926 Miss Mend.)

Mr. West is available on DVD in Flicker Alley’s set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.”

German Expressionism begins to wind down

Last year I was hard put to pick a film to represent the German Expressionist movement in the top ten. I chose Erdgeist but mentioned Schatten and Raskolnikow as runners-up. By 1924 there were fewer Expressionist films released, though the movement would linger on until 1927, mainly carried on by the two greatest directors who had worked in the Expressionist movement: F. W. Murnau and Fritz Lang. Each of these contributed a classic film in 1924: Murnau’s The Last Laugh and Lang’s two-part epic: Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge).

The Last Laugh isn’t really Expressionist. The sets are mildly in the style, but what really fascinated Murnau at this point was the freedom of camera movement introduced by French Impressionism. He set out to make a character study. Emil Jannings plays a doorman in a large hotel (none of the characters’ names are given). His regal bearing and fancy uniform bring him respect among his fellow employees and from relatives and neighbors in the lower-middle-class neighborhood where he lives. He has aged to the point where he carry large luggage and is abruptly demoted to work as a rest-room attendant.

Murnau introduced what came to be known in Germany as the entfesselte Kamera, the “unfastened camera,” beginning in the opening shot where an elevator with a grill descends, carrying the camera and dramatically revealing the lobby. Murnau may have been directly influenced by one of last year’s top-10, Cœur fidèle, where Epstein put his camera on a spinning-swings carnival ride. Murnau saw other uses for the device. Like the Impressionists, he conveyed drunkenness through moving camera, though in this case he put the actor and camera on a turntable, so that the room spins past behind Jannings, conveying the dizzy happiness of the doorman at a party (above).

Using more imagination, Murnau follows sound with his camera. As the party ends, musicians exit to the apartment-block courtyard, and one plays a final tune under the window. Starting with a close-up, the camera “cranes” diagonally up and backward until the men are in long shot. A cut takes us to the doorman inside, happily listening.

Actually the camera was not on a crane. Murnau and cinematographer Karl Freund affixed a track over the courtyard with a small metal elevator underneath, so that the camera could move both back and forth and up and down. The camera was not literally unfastened in these cases, but it looked like it was.

Murnau wanted to end the film on a grim note with the protagonist seated alone in the hotel rest room. Commercial considerations led to a happier ending, however, with him unexpectedly becoming wealthy. The twist was so outrageous that Carl Mayer, the scenarist, considered it a comment on Hollywood’s insistence on happy outcomes. Hence the English title The Last Laugh. The original German means “The Last Man.”

The Last Laugh got distribution in the USA, but it was not a success. Hollywood practitioners studied it, though, and started hanging cameras from tracks themselves and trying other tricks. The track backward above a long, laden banqueting table soon became a cliché of Hollywood cinema.

Murnau would make two more mildly Expressionist films, Tartuffe (1925) and Faust (1926) before heading to Hollywood to make the ultimate hanging-camera film, Sunrise (1927)

The Last Laugh is available from Kino in the USA and Eureka! in the UK.

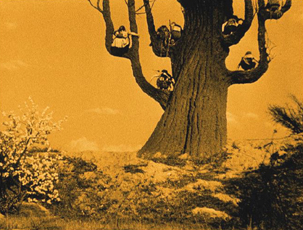

One of my favorite films of the 1920s is Lang’s two-parter, Die Nibelungen: Siegfried and Die Nibelungen: Kriemhilds Rache (Kriemhild’s Revenge). An adaptation of the ancient German myth, it mostly proceeds at a stately pace until the final battle scene. Some may find it slow, especially when compared with the lively, suspenseful Dr. Mabuse der Spieler (1922) and Spione (1928). Yet its leisurely presentation is appropriate to the subject matter. Equally important, lingering over images allows us to notice the details of the extraordinary settings and costumes, with their busy decorated surfaces and their startling arrangements within the shot.

Take the image at the top of this entry. Brunhilde, having been forced to marry King Gunther against her will, envies her sister-in-law Kriemhild, who has married Siegfried, the man Brunhilde loves. In this shot, Brunhilde mounts the steps of Worms Cathedral to confront Kriemhild and assert her right to enter the cathedral first. We see her from behind and then at the upper left as her ladies follow her, wrapped in their patterned hoods and black cloaks, creating an almost abstract composition. Lang build the enormous stairway outside the cathedral in two stages and then used the set imaginatively to stage several ceremonies and dramatic conflicts.

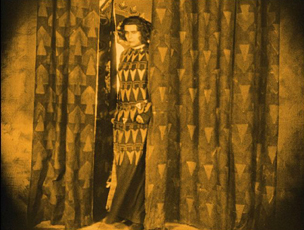

What makes this film Expressionist, I would argue, is the way the actors and settings interact, as in this moment when Brunhilde pauses by her window and then comes forward through the slightly parted curtain, exiting left. She pauses in the opening, her dress seemingly becoming part of the curtains for a moment.

The similarity and the pause have no narrative function, but it’s a very Expressionist composition. Insistent symmetry and acting also contribute to the style. In the second plot, the Hunnish King Etzel asks for Krienhild’s hand in marriage. She agrees on the condition that he will aid her in exacting her revenge on Siegfried’s killers. Upon her move to the land of the Huns, the style becomes a more familiar sort of Expressionism, with distorted trees and buildings that looks like they were built of mud that settled oddly before drying:

The elements of the German tales are all here: love, betrayal, suicide, revenge, presented in images worth savoring.

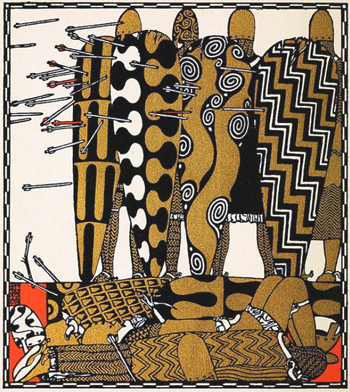

Lang was inspired in his approach to the film’s visuals by some illustrations by Carl Otto Czeschka for a 1909 retelling of Die Nibelungen published in 1909. The heavy decoration on the knight’s shields and many other surfaces in the film somewhat resemble this image, for example:

Yet the resemblance is far from exact. Clearly Lang used elements from these illustrations and took them off in his own direction.

The film has recently been restored and looks great on Blu-ray. Kino in the US and Eureka! in England have brought it out. Both have DVD editions as well.

Scandinavia’s golden age drawing to a close

During the first half of the 1920s, the Swedish cinema was a victim of its own success. Victor Sjöstrom (who has figured in these lists in 1918 and 1921, as well as in our “Lucky ’13” entry), had headed to MGM, becoming Victor Seastrom. In 1924 he released his first two films in 1924: Name the Man and He Who Gets Slapped. The latter was the newly formed MGM’s first in-house production to be released. It was a huge success, no doubt in large part due to the growing stardom of Lon Chaney, and it put the studio on the map and allowed Seastrom to stay in Hollywood, notably for The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

Mauritz Stiller (also a previous top-10 choice) was about to head for Hollywood as well, but his final Swedish film is one of his finest. Gösta Berlings Saga, a epic adaptation of Selma Lagerlöf’s novel, was made in two parts lasting over three hours. Many people will know it as the debut film of Greta Garbo. Fans should be forewarned that she is an important character and appears in the early and late scenes but disappears for a long stretch in the middle.

[December 30: As our friend Antti Alanen points out, Garbo had already acted in a comedy, Luffar-Petter (Peter the Tramp, 1922) and in some short advertisements.]

The film begins with Berling, a drunken pastor in a small town, being relieved of his duties. He ends up being taken in the “Chevaliers” at Ekeby the country estate of Margaretha Samzelius, a tough middle-aged woman who runs a group of foundries she has inherited from a lover. The Chevaliers are a group of hangers-0n, men who can drink and laze about most of the time but who must be charming and entertaining at Samzelius’ many dinner parties. Berling has a number of chances to redeem himself but ends up harming the people around him and sinking lower into despair. He is finally redeemed by the love of the Garbo character, Elizabeth, the new bride of a wealthy neighbor, to whom, it turns out through a technicality–and happy coincidence–she is not actually married.

Hansen and Garbo make a gorgeous couple (below left), but they are upstaged by the great Swedish stage actress Gerde Lundequist as Samzelius:

As usual, the film contains lovely scenes in the Swedish landscapes. There are some impressive night sleigh rides, including a famous scene in which Berling and Elizabeth are chased across a frozen lake by wolves. There is also one of the most impressive fire scenes I can recall from the silent era, as Samzelius’ efforts to smoke the Chevaliers out of the guest house where they live and inadvertently sets fire to the big main house as well.

Unfortunately the film was cut down into a single feature for its release outside Scandinavia. The Story of Gosta Berling was the main version that circulated for many years. The Swedish Film Institute restored it in stages as more footage was found, but the current print, at 183 minutes, is still missing some footage.

Beware picking up an older video release with the truncated film. The restored version was released on DVD in the USA by Kino. The original Svensk Filmindustri release (with English, French, Portuguese, German, and Spanish subtitles), is available here. The same DVD comes in a box set of six Swedish silent classics, which is widely available from the usual online sources.

Carl Dreyer has popped up on this blog several times, usually in passing. Not surprising, since David wrote a book about him way back 1981. Here he makes his second appearance on our ten-best lists (the first having been for his first feature, The President, in 1919) with Michael.

The film centers around a wealthy, aging artist, Claude Zoret. The main room of his house is decorated with several eye-catching pieces of sculpture, notably a mysterious battered head that looms in the background of many shots. Is it one of Zoret’s own works? Is it part of a collection of ancient statues? Much of the action takes place here, which has led some historians to place Michael in the tradition of the Kammerspiel. David calls it a borderline case. There are certainly scenes that leave Zoret’s studio, most notably one in a large theater set.

The film has been hailed as an early treatment of homosexuality. Although there is nothing overtly expressed, it is hard not to read such a subtext into the action. Zoret, wonderfully played by Danish director Benjamin Christensen, has many guests and admirers visit him, creating a little all-male coterie. He has taken in a young protegé, a very beautiful and very young Walter Slezak. Zoret refers figuratively to Michael as his son, but there seems to be another tie between the two. Moreover, there may be a hint that Charles Switt, a journalist apparently writing a biography of Zoret (at the center of the frame above), feels some jealousy toward the young man.

Trouble begins when a princess comes to commission a portrait from Zoret. Although he usually doesn’t do commissions, he is intrigued by her face and agrees. During her visits to the studio to pose, she meet Michael, who is immediately smitten. The affair continues as Michael becomes increasingly inconsiderate to Zoret,borrowing money to continue the affair and missing an important showing of his work. In contrast, Zoret shows unwavering generosity to Michael, despite being devastated by his desertion.

Ultimately Zoret paints his last work, showing an elderly, lonely man against a barren seascape. It is hailed as a masterpiece at a party which Michael does not attend.

The character study proceeds at Dreyer’s usual formal pace, and yet it is never dull. As much as any of his silent films, it looks forward in tone to his later sound ones.

A very nice print of Michael is available in the UK from Eureka! (not deliverable to the USA); Kino released what I assume is the same print in the USA.

She was nothing but a poor flower-maker

Every now and then I want to put a film on the list which is impossible to see unless you happen to live near one of the archives that has a print and they happen to program it. Still, in the hope of inspiring someone to restore it and make it available, I proceed.

The film is Jean Epstein’s L’Affiche (“The Poster”). Epstein first made our list last year for the much better known Cœur fidèle. L’Affiche is a bit like the earlier film, a simple melodrama made in the French Impressionist style. Its situation is highly conventional, and its plot depends on a massive coincidence.

The heroine is introduced as Marie, one of several women making artificial flowers. On her lunch break she thinks back to a romantic day she spent in the country. There she meets a young man, Richard. The couple go to an expensive restaurant, and Richard seduces Marie, and then abandons her, driving away alone the next morning.

Three years pass, and Marie has a small child, also named Richard. She enters him in a contest for the most beautiful child, with a cash prize, offered by an insurance company that wants to put the winner on their advertising posters. The boy wins, and Marie signs a 10-year contract for the rights to use little Richard’s image.

The child dies, however, and Marie visits his grave. As she leaves, she sees a huge poster with his image. The campaign has begun. Everywhere in Paris she goes, she sees the poster and finally begs the insurance company to end the campaign. The boss, however, refuses. Marie begins tearing down the posters, and she is soon arrested. Epstein handles the arrest scene without an establishing shot but builds it up through close-ups.

Initially we see only the back of Marie’s head and her arms tearing down a poster. There a cut-in to slightly closer framing as a policeman’s hand comes into the shot and touches her shoulder. A third shot shows her turning to the officer and staring in a way that suggests she is becoming mentally unbalanced. Finally a long shot establishes the scene as a second policemen enters to help arrest her.

It’s the sort of gradual revelation of space that Kuleshov was working with at the same time.

The boss of the insurance company is informed of this and sends his son to file a complaint against her. New copies of the poster are being put up all over town. The son is none other than the Richard who seduced Marie years before. Hearing her tale, he asks her forgiveness and takes her home to his parents. The father forbids their marriage, they marry anyway, and eventually (after his own younger child dies!), the boss blesses the marriage and agrees to take down the posters.

Summarized baldly, it sounds like an impossible plot to take seriously, but Epstein’s delicate, understated approach in presenting it and Nathalie Lissenko’s affecting performance as Marie manage to make it a great film. It’s full of Impressionist moments: Marie’s memory of her romantic day with Richard, a dance scene with rhythmic editing, a dream sequence, and plenty of gauzy shots and fancy wipes at transitions.

Earlier this year I complained because L’Affiche was not included in the big new box set of Epstein’s work, despite almost everything else from the period being there. It’s also not on the box set of films made at the Russian emigré studio, Albatros, even though Epstein’s other three Albatros films are there. I don’t whether there are rights problems or there simply isn’t a good enough print.

At least one streaming service claims to have L’Affiche available, but a search turns up numerous complaints about the site.

I should make mention of one other Impressionist film that came out in 1924. Perhaps it should be on the list rather than L’Affiche. It’s Marcel L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine. L’Herbier appeared on our 1921 list for El Dorado, and even then I expressed reservations. Most of his films seem cold and by-the-numbers to me, not to mention a bit pretentious. But his films were historically important, and L’Inhumaine was influential in its use of art deco sets. At one time the film was available on DVD, but it seems to be out of print.

Three funny men …

And no, it’s not Chaplin, Keaton, and Lloyd this time. Chaplin didn’t release a film in 1924. His next would be what many would consider his funniest feature, The Gold Rush.

Over the years I’ve stressed that during the 1910s, the three great comics were working in shorts, honing their filmmaking and working up to their great series of features. By 1923 they had fully made the transition: Lloyd made Safety Last and Keaton Our Hospitality. Safety Last had a simpler plot, structured mainly by the stages of the hero’s climb up a building. Keaton went further with a complex story of a romance blooming between members of feuding families, using multiple locations, a developing causal line, and clever motifs. (We analyze it in Chapter 4 of Film Art: An Introduction.)

In 1924, Lloyd achieved a similar complexity with Girl Shy, one of his greatest films. He plays a bashful young tailor’s assistant who is terrified of women. Yet in secret he writes a guide for seducers, taking on the narrational persona of a jaded man of the world. Clearly he has taken his inspiration from movies of the day. The imaginary scenes from his book dramatize his success in gaining the love of a vamp (see bottom) and a flapper. The publishers decide that the book is so over the top that they will publish it as a comic story. During all this Harold develops a relationship with Mary, a quiet young woman from a wealthy family. When her father tries to buy Harold off, he pretends to spurn Mary. She is about to marry a rich man, but Harold determines to stop the wedding.

There develops one of the most epic chase scenes in all silent comedy, and indeed all cinema, as Harold commandeers all manner of vehicles, from cars and wagons to a firetruck and a speeding trolley (above).

Even Keaton never outdid that one. But from 1923 to 1927, these two each created a string of innovative, carefully crafted, hilarious films.

Girl Shy used to be available in a 3-DVD set from New Line, but that is no longer available–though one optimistic third-party seller offers it, still sealed in plastic, for $399.99). Now the individual releases of each DVD seem to be slipping out of print as well. Volume 1, which contains Girl Shy, is definitely out of print. Be forewarned: Volume 2, which includes the wonderful 1927 film The Kid Brother (look for it on a future list) seems like it’s not long for this world, and the same is true of Volume 3, with For Heaven’s Sake (1926).

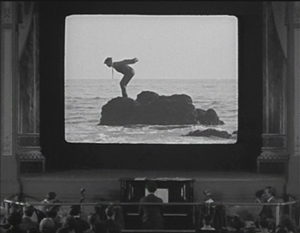

It was difficult to choose between Keaton’s two major releases of 1924, Sherlock Jr. and The Navigator. I chose the former mainly because of its perpetually astonishing transition from the frame story of a small-town projectionist unlucky in love to his dream of himself as a sophisticated detective. His dream takes the form of a movie, and the sleeping projectionist walks through the theater and into the onscreen action. With extraordinary precision, Keaton maintains a long-take framing of the pianist and audience in the auditorium while the hero onscreen undergoes a series of unexpected shot changes. In each he is in the same pose and position within the screen, but the backgrounds change arbitrarily, as when he begins to dive from a rock into the ocean and finds himself landing in a snowdrift:

The result is a marvelously convincing technical feat, giving the illusion of being a single shot as far as the theater is concerned and on the movie screen a character wandering through an appropriately dream-like series of edited shots. In general, Keaton was the most adept of the three great comics at using cinema technology to create gags, and this is his most elaborate attempt. (Though see also his short, The Playhouse, in which multiple exposures, flawlessly managed in-camera, create Keaton clones that play all the roles.)

The plot of the dream emerges after this virtuoso transition, and it remains hilarious throughout. The chase, while not quite as dazzling as the one in Girl Shy, has considerable variety of vehicles (one wonders if the two comics were consciously trying to best each other), including a passage where the hero rides the handlebars of a speeding motorcycle, unaware that the driver has fallen off.

Kino has packaged Sherlock Jr. together with Keaton’s early feature, The Three Ages (1923), and released them both on DVD and Blu-ray.

The third funny man was Ernst Lubitsch. The Marriage Circle was his second Hollywood film, and one of his best. Lubitsch had started out as a comic in silent shorts in Germany, but unlike the famous Americans, he entirely gave up acting to direct. Not that he directed only comedies, but his best films, including Lady Windermere’s Fan, Trouble in Paradise, and The Shop around the Corner, fall into that category.

The Marriage Circle is a light romantic comedy, following a chain of flirtations and misunderstandings. Prof. Stock has realized that his pretty young wife Mizzi has begun to neglect and nag him. She is soon attracted a newlywed, Dr. Braun. Mizzi happens to be an old friend of Braun’s wife Charlotte, which gives her opportunities to flirt aggressively with Braun. Charlotte is in turn admired by Braun’s medical partner, Dr. Mueller, though she laughs off his attempts to woo her.

It has often been pointed out that Lubitsch is a director of doorways. That’s not always true, but The Marriage Circle is built around visits. The five characters visit each other in various combinations, and the string of attempted seductions and jealousies builds. Stock encourages Mizzi’s pursuit of Braun, since he wants an excuse for a divorce. Charlotte naively pushes Braun into visiting Mizzi at home when she plays sick.

The sets and especially the doorways play a big role. Characters pause in doorways to take in a compromising situation they have interrupted. At one point Mizzi comes to Braun’s office. Mueller spots them in an embrace, but Braun claims he’s hugging his wife. Eager to alienate Charlotte from her husband, he opens the office door to reveal Charlotte in the waiting room:

This is the first film where one can see the “Lubitsch touch” in action. It’s an ability to use film techniques to hint at something naughty. Here the innuendos are aimed at the characters. We know more than any of them does, and the humor arises from watching them misinterpret what they see and hear. When they finally learn of their mistakes, they end the “circle” of the title.

The Marriage Circle is available to rent or buy in digital form on Amazon. I know nothing about the source or the quality. The only DVD easily available is a region 2 French one under the rather blah title Comédiennes. The print is distinctly soft (as the frame above suggests) but acceptable until a better one becomes available.

… and one not so funny

Greed is often spoken of as the film that historians and buffs would most like to see rediscovered. Part of it survives, of course–about two hours out of the original eight or so. Its producer, MGM, had it was edited down into a reasonably coherent feature, mainly by cutting out a number of characters and their subplots. I won’t say much about the film here, since it is already quite well-known.

The film is an adaptation of Frank Norris’ novel McTeague done in a naturalistic style, which was unusual for Hollywood films of that or any other day. It follows McTeague, an unlicensed dentist, who steals his friend Marcus’ girlfriend, Trina, and marries her. Their luck fluctuates, as Trina wins a lottery and McTeague is thrown out of work for not having a license. Trina becomes an obsessive miser, and McTeague, by now an alcoholic, murders her and flees to Death Valley with her money.

I find a lot of Greed heavy-handed and obvious. (I prefer the simpler Blind Husbands, which made our ten-best list for 1919.) It has an interesting style, however, with a lot of proto-Wellesian deep focus and low angles, complete with, in the case of the frame above, a hint of a ceiling. The final sequence in Death Valley is also very effective.

Apart from being 75% lost, Greed has never been released on DVD. (See Indiewire for comments on this.) In 1999 Turner Classic Movies edited a four-hour version, inserting production stills to suggest the missing scenes. This was reasonably effective, but it seems impossible to find a print of it that is not washed out and fuzzy. We’ve tried taping off TCM, as well as buying the VHS and laserdisc releases of that version. They all verge on unwatchable. I hope that the situation is not left where it is and that a true restoration is eventually done. My frame above comes from an archival 35mm print, so clearly better material exists.

The lost film that I would most like to see discovered is Lubitsch’s Kiss Me Again (1925). Given that it was made right before Lady Windermere’s Fan, there’s a good chance that it’s a masterpiece.

One of a kind

Last year I put Man Ray’s experimental short, La retour à la raison, on the list. Comparing experimental shorts to fiction features, though, seems unfair. This year I’m separating out the experimental category and will try to choose at least one film each year.

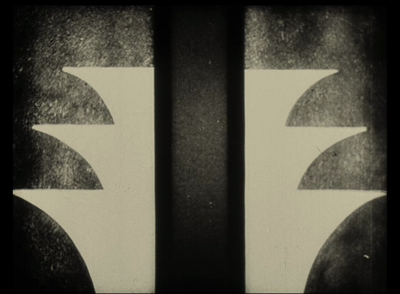

This year it’s Walter Ruttmann’s Opus 3, the third of his four films done with abstract animation.

All of the Opus films plus other Ruttmann shorts are available on a DVD set with Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt and Melodie der Welt. If you want to sample just Opus 3, which is about four minutes long, it has been posted multiple times on YouTube. Although a bit dark, this is the best copy I’ve found, and it has a nice, appropriate score by Hanns Eisler.

Bernard Eisenschitz made the connection between Lang and Czeschka in his massive Fritz Lang au travail (Cahiers du Cinéma, 2012) , pp. 38 and 42. Czeschka’s Nibelungen illustrations can be see along with the entire book on the Museum of Modern Art’s website, with a page-turning feature and the ability to enlarge the pages considerably. Individual illustrations can be found with a Google Images search on “Czeschka” and “Nibelungen.”

Thanks to Jonah Horwitz for a correction.

Girl Shy

Adieu to Vancouver 2014

Jauja.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended this past Friday. I had hoped to post a wrap-up entry over the weekend, but illness intervened. Herewith a summary of several films I enjoyed this year.

Too clever by half

Some films are obviously and thoroughly pretentious. This year Field of Dogs (Lech Majewski, 2014) fell into that category. I had had high hopes for it, since I very much liked Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross at the 2011 festival. Unfortunately, it’s a completely different film, overcomplicated and, for me, nearly unwatchable.

Two film, however, suffered from a different problem. They had absorbing stories and interesting stylistic approaches. I enjoyed both very much–except for unwise additions, in each case unnecessary and annoying.

Stations of the Cross (Dietrich Bruggemann, Germany, 2014) revolves around Maria, an adolescent girl raised in a household where a strict, old-fashioned version of Catholicism is practiced. Bruggemann takes the not uncommon approach of filming each scene in one lengthy, and in most cases static, take. In the opening scene, a priest instructs a small class of children about to take First Communion. The camera is placed in a planimetric framing, a technique used in several shots in the film:

As the lesson continues, Maria, seated to the priest’s right, gradually emerges as the student most versed in the topics under discussion. She stays after the others leave and hints to the priest that she wants to sacrifice herself to earn a miracle for her four-year-old brother, who has never spoken. Her belief that she must deny herself virtually all pleasures, comforts, and even necessities, as well as her guilt over the slightest perceived infraction, become increasingly apparent across the narrative. Her arguments with her harsh and inconsistent mother, who dominates the family, reveal her suffering. Despite the static shots, the story is never boring, and a scathing indictment of this brand of religious extremism builds up.

The problem is that Bruggemann inserts chapter titles before each scene/shot, numbered and with the descriptions of the fourteen Stations of the Cross. This inevitably connects Maria’s sufferings to those of Jesus. Each scene contains some parallel, however tenuous, to the station that it is supposed to illustrate. I found this distracting and occasionally ludicrous, as when the title describing Christ’s being stripped of his clothing cuts to a shot of a partially undressed Maria seated on a doctor’s examining table. (Jay Weissberg’s review for Variety sees deliberate humor in the film, but as far as I could see, Bruggemann takes all this as deadly serious.) This could have been an excellent film without the insistence on allegory, but as it is, one must try to ignore the interruptions to focus on the story.

Something rather similar happens in Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, Argentina, 2014). Again there is an absorbing story, though a very different one. In nineteenth-century Patagonia, a Danish engineer is doing surveying work to help a military group determined to wipe out the indigenous population. When his daughter runs off into the forbidding desert with a young soldier, the engineer follows on his own and experiences a series of increasingly disturbing and mystifying incidents, including some that could be classed as magical realism.

This is fascinating stuff, and in the print we saw, the beautifully composed landscape shots (almost the entire film takes place out of doors) were presented in a masked format reminiscent of old lantern slides or stereoscope images (see top, the opening one-shot, long-take scene). Most of the images from this film on the internet are in a more conventional 1:66 ratio, but the masked version seems far superior. One can only hope that the video release preserves it.

It’s a lovely, evocative, disturbing film, but just as we see a shot of the protagonist disappearing into a valley in a bleak landscape of black volcanic rocks, there is a cut to an epilogue set in a beautiful Danish castle. The daughter wakes up and goes for a walk with some dogs. End of film. How this is supposed to relate to the preceding story is a mystery, and one which thoroughly undercuts the tension slowly built up over the course of the Patagonian-set story. The scene of the hero disappearing would have made a fitting ending, leaving the solution to the tale’s mysteries open-ended.

I note from a recent story in Variety that Alonso has been chosen as the second filmmaker to be hosted in the Film Society of Lincoln Center’s new “Filmmaker in Residence” program. That’s good news, I think, but I hope Alonso will trust more in his story-telling ability and less in flashy tactics like this pointless epilogue.

Brief notices

One director who displays such trust is Alejandro Fernández Almendras, whose Chilean revenge tale To Kill a Man (2014) is both entertaining and morally and psychologically complex. We are almost entirely confined to the presence and knowledge of Jorge, a forest ranger who has grown accustomed to the casual violence in the neighborhood where he lives. He tries to avoid trouble, but his family is increasingly harassed by Kalule, a loathsome petty gang leader. As Jorge is mugged, his son is shot and then wrongfully imprisoned, and his house pelted with stones and threatening messages, he doggedly insists on going through the police, while his wife becomes increasingly frustrated with their lack of response.

Finally, after Jorge’s daughter is assaulted and nearly raped, he decides to act and sets out to eliminate Kalule. The film then follows his patient, careful planning, culminating in an understated but riveting long take of the truck in which Jorge has his victim trapped as he systematically sets up the mechanics of the killing. The death itself is not shown:

Hitchcock has said that in making Torn Curtain‘s big fight scene in the farmhouse, he wanted to show just how physically difficult it is to kill someone–as opposed to the seemingly effortless killings that fill American genre films. Almendras’ film is almost entirely about how difficult it is in all ways. Jorge takes a long time making his fateful decision, in executing it, in dealing with the body and evidence, and in living with what he has done. Most spectators, attuned to more conventional revenge plots and frustrated by Jorge’s initial resignation in the face of intolerable injustice, are probably cheering him on from an early point in the plot. But, as Almendras thoroughly shows us, it just isn’t that easy.

Charlie’s Country (Rolf De Heer, 2013) also centers very tightly on a protagonist beset by difficulties, but it sets a very different tone. It’s another Australian film focusing on aborigines and their problems under the rule of the white majority. Charlie is a genial elderly man living in impoverished circumstances in a village set aside for aborigines and run by local police. Their laws mystify him. His gun is taken because he cannot afford a license, and when he fashions a spear for hunting for food, it is taken away and destroyed as a dangerous weapon.

His health declines so far that the authorities send him to a hospital in a city far from his home, an apparent signal that he is dying. Instead, he escapes, lives with some street people, and finally makes his way home.

The film is entertaining enough, though it deals with familiar subject matter. It exists, though, primarily as a love letter to David Gulpilil, the most successful Australian aboriginal actor. His first film is also one of his best-known outside Australia, Walkabout, which I saw when it first came out, just after I had gotten my BA and was about to commence film-studies as a graduate student. (It’s a bit disconcerting to watch him playing an old man here and realizing that he is three years younger than me!) Gulpilil turns in an endearing performance that pretty much carries the movie.

I enjoyed and was impressed by Russian director Andrei Zvyagintsky’s Leviathan (2014), though I’m not sure it quite lives up to all the hype following its debut in competition at Cannes, where it won best screenplay. The story centers around the owner of a sprawling, dilapidated garage in a declining fishing port on Russia’s northwestern coast. He struggles to prevent a corrupt local mayor from appropriating his property illegally. (The hypocritical official wants to use the land to build a church to further his own reputation.) At the same time, the protagonist has remarried, and he must deal with his teenage son’s reluctance to accept a young stepmother.

The depiction of modern Russian society in the provinces is a grim one, albeit one displayed in sweeping landscape shots that suggest the waste of this stunning region. Many scenes involve the characters putting away great quantities of vodka. These include a hilarious set-piece in which the family and friends drive into the countryside for a drunken picnic complete with a shooting competition using portraits of historical Soviet leaders as targets.

Leviathan will be released in the USA by Sony Pictures Classics on December 31.

Papusza (Joanna Kos-Kralize and Krzysztof Kralize, 2013) is the second new black-and-white Polish film I’ve seen this year. The first was the much-heralded Ida (Pawel Pawlikowski, 2013), an austere tale of a young woman in the 1960s, about to take her vows as a nun when she learns that she comes from a Jewish family persecuted during World War I. Papusza is a more easily engaging film, with a relatively fast-moving historical drama set among Poland’s Roma (“gypsy”) population.

Papusza centers around Bronislawa Wajs, the first Roma woman to learn to read and write; she became a well-known poet nicknamed Papusza. The film adeptly balances sympathy for the Roma group at the center of the story, the victims of racial prejudice, with a clear-eyed depiction of the less savory aspects of Roma culture. Girls, kept ignorant and oppressed, are married off at a young age. The Roma society practices its own prejudices, rejecting any interactions with people outside their clan and treating non-Roma as fair game to be fleeced at any opportunity.

The lively culture of the Roma and their closeness to nature are shown in impressive landscape scenes, as in shots of the caravans on the move through bucolic countrysides or when the band sets up a camp and market outside a traditional church (below).

As of now there is no indication that the film will receive an American release. The only DVD available seems to be the Polish one, with no optional subtitles. Various small streaming services claim to be offering it, but again, possibly without subtitles and in some cases with timings that don’t correspond to the original 131 minutes.

And so another year at Vancouver has ended. As usual, we are left with the feeling that this event is one of the most pleasant ways to catch up with a huge amount of what is happening in world cinema.

Papusza

Addio Bologna 2014

Okoto and Sasuke (1935).

DB here:

Some final notes on this year’s Cinema Ritrovato. Kristin has more when I’ve finished.

Poland, very wide

The First Day of Freedom (1964); production still.

Revisiting a couple of the Polish widescreen classics Kristin mentioned earlier, I’d just add that The First Day of Freedom struck me as merging that heaviness often ascribed to Polish cinema with casual shock effects, as much visual as dramatic. It’s not just the opening shot, with the camera descending implacably to reveal layers of activity in a POW camp before settling on barbed wire in the foreground, made as big as the chains on an ocean liner’s anchor. A symmetrical vertical lift ends the film, rising through floors of a nearly destroyed church tower, revealing a half-shattered Madonna and a looming bell, to float back up to the sky.

As in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, gunfire not only cuts you down but sets you on fire. A Nazi dead-ender, holed up in the steeple and dying from his wounds, orders his girlfriend (“Whore!”) to take over his machine-gun nest. Since she’s been raped by wandering refugees early in the film, she has every reason to fire on the Poles, which she does with animal abandon. A Polish bullet cuts short her shooting spree, and then the camera launches on its remorseless movement heavenward. The primal force of this movie, especially the climax, suggests that Alexander Ford and Samuel Fuller have more in common than I’d suspected.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Yutkevich seems to be keeping up with the Young Cinemas of his day. The film is plotted as a series of flashbacks, alternating the present (Lenin in prison) with pieces of the past, sometimes out of chronological order. He imagines himself striding across a battlefield, conveyed by him walking in place against a blatant back-projection. Late in the film, newsreel footage gets stretched and distorted to fill the ‘Scope format, as in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962). The experimentation with the soundtrack seems likewise rather modern. The noises are filtered nearly as strictly as in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu, so that sometimes we hear only Lenin’s footsteps in a city street.

Lenin not only narrates the film but “quotes” the whole dialogue of the scenes; we never hear any voice but his. Reminiscent of passages of The Power and the Glory (1933) and the entirety of Guitry’s Roman d’un Tricheur (1936), this device blankets the movie with Lenin’s thoughts, feelings, and political analyses. It’s scarily evocative of that booming voice-over narrator that Soviet cinema imposed on imported films. Denied subtitles and dubbing, audiences were obliged to listen to an impersonal voice drowning out the actors with its sovereign interpretation of the action. I wouldn’t put it past Yutkevich to be slyly alluding to this Orwellian voice of authority.

1914 fashionistas and 1940s fakers

Maison Fifi (1914).

For sheer dirty fun I have to recommend Maison Fifi by Viggo Larsen, a Danish director working in Germany. Here situation comedy meets notably horizontal sight gags. A young couturier cozies up to the officers stationed in her town, hoping that their wives will buy her wares. Her first encounter takes place outside the officers’ quarters, as each man, from private up to general, spots her and starts to flirt before being ordered aside by a higher-up. Part of the humor comes from the strict adherence to the table of ranks, part from the fact that each dislodged officer enjoys watching his superior get taken down.

Later, on a lark, some officers swipe one of Fifi’s dummies and take it to a tavern. When their wives surprise them there, they stow the mannequin in a distant phone booth. As they expostulate with their wives in the foreground, the dummy sits unmoving in the window of the booth far on frame right. Meanwhile, increasingly annoyed customers line up outside the booth. The dummy is more visible in projection than in my still, but Larsen also obliges with a cut-in.

In a very logical reversal, Fifi is at the climax caught in a boudoir and must pretend to be one of her own mannequins. This affords the officers an excellent pretext to undress her. Today the scene yields a vivid sense of the hooks, buttons, and stays that women, and men, of 1914 had to contend with.

Faked identity was a motif of the festival’s Hitler strand. The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler (1943) centers on a man with a knack for mimicking his Fuhrer and accidentally becomes his double. In a series of twists, both he and others try to kill the original, but confusion ensues and leads to a very downbeat ending.

The same premise gets a different workout in The Magic Face (1951), a film as puzzling as its title. Luther Adler delivers a performance at once peculiar and virtuoso. A stage impersonator’s wife is stolen away from him by Hitler. Escaping from prison, he decides to get his vengeance by posing as a servant and gaining access to the dictator. He kills Hitler and takes over his identity. Thereafter he cunningly fouls up the prosecution of the war by an ill-timed invasion of Russia, etc. His general staff are baffled and even try to kill him, but he represses all resistance.

The weirdness of this speaks for itself. In addition, the film doesn’t explain how Hitler’s new mistress fails to realize that her paramour has been replaced by her husband. Perhaps more striking, we wonder whether the impersonator might have taken a little trouble to alter other Nazi policies, e.g., the Final Solution. No less odd is the frame story, narrated by celebrated war correspondent William L. Shirer. There he maintains that this account was relayed to him by the wayward wife, who survived the fire in Hitler’s bunker. An independent production directed by Frank Tuttle (recently under HUAC pressure for his Communist affiliations), The Magic Face was judged by Variety to provide “a dramatic and suspenseful story which would have had far greater audience impact five or more years ago.”

Talking, in and out of sleep

The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933); production still.

The Japanese cinema of the 1930s through the 1960s has been one of the very greatest national film traditions. I once characterized it as the Western cinephile’s dream cinema: a relentlessly commercial industry that has given us dozens of indisputable masterworks. Yet it seems that every few years it’s necessary to remind western publics of this nation’s titanic accomplishments. Packages circulated by the Japan Film Library Council in the 1970s have been followed by retrospectives and one-off touring programs at rather long intervals; the Mizoguchi series is a recent example.

Another effort to draw Japanese cinema to the spotlight, “Japan Speaks Out!” has become a high point of Cinema Ritrovato over the last three years. Curators Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström deserve credit for assembling new prints of early talkies, grouped by studio. As in previous years, some of the titles were familiar to specialists, and a few to generalists (Ozu’s The Only Son being this year’s example). But there have been several new discoveries, and the Ritrovato audience has responded enthusiastically. This year the films were screened twice, often to jam-packed halls. The sessions were introduced with brevity and point by Alexander, Johan, and Tochigi Akira of the National Film Center of Tokyo.

This year’s batch focused on the Shochiku studio, more or less the MGM of Japan. Shochiku enjoyed financial stability because of its theatre holdings (both cinemas and live-performance venues) and its address to a modernizing, western-leaning urban audience. Its policies, overseen by Kido Shiro, aimed to provide movies mixing tears and laughter. Kido urged that Shochiku comedy have a melancholy cast, and that Shochiku melodrama indulge in lighter moments. This blend is familiar to us in Ozu’s 1930s works; even as sad a film as The Only Son displays a comic side when the mother falls asleep during a German talkie.

Perhaps the purest example of Kido-ism in this year’s package was one of Shimazu Yasujiro’s best films, Our Neighbor Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934). Two brothers are introduced practicing baseball, and soon we learn that one has considerable affection for the girl next door. The neighboring families are thrown into quiet turmoil when Yaeko’s sister returns home, having left her husband.

Stylistically, Shimazu is less rigorous than either Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi, but he is very skilful. Our Neighbor Miss Yae has the real Kido flavor, mixing comedy and drama and throwing in cinephile references that the studio’s young directors enjoyed: one boy is compared to Fredric March, the young people watch a cartoon featuring Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. Just as important, Shimazu enjoys throwing in a stylistic flourish every now and again–a striking, even eccentric shot that arrests our attention. As the four young people are eating in a restaurant, a very straightforward shot of them gives way to a bold composition full of peekaboo apertures. The shot enlivens the fairly routine act of waitresses delivering food; at the end, one pair stands and switches positions.

Not all Shochiku films displayed a mixed tone; we saw some fairly pure comedies and melodramas. Three self-consciously modern films showed an amused, slightly sexy concern with young marriage. Happy Times (Ureshii koro, 1933) by Nomura Hiromasa, begins with a pair of teenage boys practicing pitching and catching to the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home.” Soon they’re spying on newlyweds who are so infatuated with one another that the husband skips work to stay at home and lounge around. He’s mocked by his fellow employees and upbraided by his boss, but his wife is relentless in her sweet-talking ways. The marital bliss is disrupted by an obstreperous visiting uncle, and the couple must turn to one of the man’s old girlfriends, a tough singing teacher, to dislodge him—without sacrificing the inheritance he may leave them. Awkwardly shot and rather too prolonged, the film exemplified how loose-limbed Shochiku comedy could get.

A brace of films by Shochiku stalwart Gosho Heinosuke, The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (1935) and The Groom Talks in His Sleep (Hanamuko no negoto, 1935), showed other newlyweds with comic problems. Again the motif of spying plays a role. (Naughty voyeurism was essential to that strain in popular culture called Ero-guru-nansensu, “erotic-grotesque nonsense.”) Salaryman Komura’s pals have learned that his wife talks in her sleep, and so they drop by to hear for themselves. Unfortunately they drink so much that they fall asleep and miss the big revelation. Plot complications include a burglar, the couple’s decision to sleep elsewhere, and the revelation of what keeps the bride “sleep-talking.”

Only a little less slight is The Groom Talks in His Sleep. Here the title probably gives away too much, because the initial puzzle is why the young wife naps during the day. This scandalous dereliction of housewifely duty leads eventually to a demand for divorce until the cause, the husband’s sleep-talking that keeps her awake all night, is revealed. The family brings in a self-styled hypnotist, played with relish by Ozu regular Saito Tatsuo, to cure the groom.

Gosho is said to be the fastest cutter among classic Japanese directors, but I’m not sure that he goes much beyond what was fairly standard at Shochiku. Most of the studio’s directors working in the contemporary-life genre (gendai-geki) employed what I called in my book on Ozu “piecemeal découpage,” a breakdown of action and dialogue akin to that seen in late US silent films. What Gosho does have in abundance is different camera positions. In The Bride, our introduction to Komura’s drinking buddies takes place at a bar, and I didn’t spot any repeated setups. Throughout the two films, each composition is calibrated to a specific item of information—a line of dialogue, a reaction shot, or a change in the staging. This makes for a tidy visual texture, which is an advantage in the rather loose plotting that’s characteristic of Shochiku comedy (Ozu, always, excepted).

At the other extreme were some very serious drama, such as Mizoguchi’s relatively well-known Poppies (Gubinjinso, 1935) and the more obscure Mizoguchi-supervised Ojo Okichi (1935). There was as well Okoto and Sasuke (Shunkinsho: Okoto to Sasuke, 1935), another Shimazu work. It’s based on a Tanizaki Junichiro tale of male devotion passing into love and masochism. Okoto is blind, but her family can afford to pamper her. She takes up the koto and the family’s young servant Sasuke faithfully escorts her to her music lessons. She often treats him disdainfully, but she insists on his company, and so gossip grows up around them. Sasuke’s loyalty is tested when Okoto is wooed by a vacuous but persistent suitor. Spurned, he arranges an attack on her, which triggers Sasuke’s ultimate sacrifice.

Shimazu treats this story with a calmness that builds up tension between the often wilful Okoto and the simple-hearted Sasuke. The discreet simplicity of the film’s technique, excepting the violent climax, can be seen in an almost throwaway moment. Sasuke as been assigned to tutor two of Okoto’s students, and they laugh at his efforts. As they rise, Shimazu cuts to a new angle, putting them the background and showing Okoto is shown growing anxious in the foreground.

Keeping Sasuke out of focus and far back allows Shimazu to stress a micro-movement in the foreground: Okoto’s shift from sympathy for Sasuke to her usual imperious annoyance. After unfolding her hands, she clenches her right hand and softly strikes it on the edge of the brazier.

As Okoto turns to summon him for a mild dressing-down, still keeping her little fist extended, Sasuke has shifted his position slightly so that he is a more active responder to her.

This sort of directorial discretion, so characteristic of classic Japanese cinema, seems today to come from another world.

Probably the greatest revelation of the Shochiku show was another masterwork by the ever-more-impressive Shimizu Hiroshi. A Woman Crying in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933), Shimizu’s first sound film, was given its western premier. It was chosen to exemplify his experiments with sound–experiments that induced Ozu to try his own hand at talkies.

Mining work in Hokkaido brings day laborers by ship, along with women who wind up serving them drinks and perhaps something more. Most of the action takes place in a tavern with a bar downstairs, women’s rooms on the next story, and a small upstairs where the mysterious, somewhat cynical Chuko keeps her daughter. Kenji and his boss become rivals for Chuko, and a young woman drawn into prostitution further complicates the situation.

After only a single viewing, I’m pressed to say much more than noting that Shimizu sacrifices some of his geometrical precision (discussed here) to a more naturalistic treatment of the bar’s space and more experiments with chiaroscuro lighting. A somewhat flamboyant scene, in which our view of a fistfight is mostly blocked by a high wall, shows how Shimazu was trying to let sound do duty for the image. The title has multiple implications: the woman we see crying at the outset is Fuji, the girl initiated into the trade; but at the end, Chuko is weeping. Moreover, as Alexander Jacoby pointed out, the scenes we see are all set in winter, although the ending suggests that the couple that is created will find spring elsewhere. Long unavailable in its Japanese VHS edition, A Woman Crying in Spring is ripe for Western distribution.

Last notes from Kristin

Despite my commitment to the Polish, Indian, and Japanese threads, I was able to fit in a film or selection of shorts now and then.

On the afternoon of the opening day, the first “Cento Anni Fa” program for 1914 included a couple of interesting items. One was La guerre du feu, a French film directed by George Deonola. It dealt with a tribe of fur-clad cavemen who have captured fire but lack the knowledge to create it themselves. Thus they must tend their fire constantly and protect it from a rival tribe. In the course of the action the hero learns the secret to using tinder and flint to generate a blaze. This, it has to be said, was more interesting as an historical curiosity than as entertainment.

Not so the final film of this group, Amor di Regina (Guido Volante, 1913). Its unusual story dealt with a queen of an unnamed country who is having a secret affair with a young soldier. When the latter gets wind of a rebellious group’s plans to assassinate the king, the hero and the queen manage to spirit him out of the palace and away to exile. It struck me that in a more conventional film, the lovers would use the assassination of the king to allow them to marry. Instead they take care of the king in exile and watch for a chance to reinstate him.

Stylistically there were some impressive shots. In one, we see a close-up of the back of the hero’s head, looking out from a terrace at a group of conspirators in the distance sneaking toward the palace, and the camera racks focus from him to them–for 1913, a highly unusual way to handle a very deep composition. If anyone is contemplating a DVD/BD release of some Italian short features of this era, Amor di Regina would be a good choice.

Another 1914 program included the lovely La fille de Delft, which, along with Maudite soit la guerre (which was shown at one of the Piazza Maggiore screenings), is one of Alfred Machin’s best-known films. Its plot concerns a little country boy and girl who are dear friends; a variety-theater owner sees them dancing at a country celebration and takes the girl off to the city to become a star. Seeing it again, I was struck at how marvelously natural the performances of the two child actors (above) was, something that goes a long way to making this film so very affecting.

Despite the fact that all of Tati’s early short films are on the new French boxed Blu-ray set, I decided to see the Tati program on the big screen. Seen again, Gai dimanche (1935) seemed a bit labored in its humor, dealing with two layabouts who hire an old car and persuade several people to purchase day trips to the country. The situation seems more the sort of thing that René Clair could have made work, but director Jacques Berr makes it somewhat leaden.

Soigne ton gauche centers on a gawky farmhand who is mistaken for a boxer by a promoter and ends up in a practice ring with a tough opponent. Tati creates a very Keatonesque situation as the naive young man finds a book on boxing on his stool and proceeds to consult it at intervals (below). As he assumes classic boxing poses, the experienced boxer uses brute force to knock him silly.

The opening and closing of Soigne ton gauche contains a comic, bicycle-riding postman, and clearly Tati recognized the comic potential of the character. In his first directorial effort, L’école des facteurs (School for Postmen, 1946), Tati himself played the postman François, who tries to please his teacher by finding ways to deliver the mail more swiftly. The idea proved so fruitful that the film was remade as Tati’s first feature, Jour de fête. The bouncy music and many of the gags were retained, and the longer film’s success established Tati as a major director and star.

To all our friends and the coordinators of Cinema Ritrovato: Thanks for another wonderful year!

You can watch The Eye’s tinted copy of Maison Fifi here.

Miriam Silverberg’s Erotic Grotesque Nonsense offers a thorough discussion of Japanese popular culture of the 1930s. For more on Kido Shiro’s influence on Kamata cinema, see Mark Schilling’s Kindle book Shiro Kido: Cinema Shogun. I discuss trends in 1930s Japanese film style in Chapters 12 and 13 of Poetics of Cinema. For more on the restoration of Machin’s films, see our entry here.

Soigne ton gauche (1936).

Albatros soars

Gribiche (1925).

Kristin here:

Lazare Meerson was one of the great set designers of the late silent period and into the 1930s. His name may not immediately ring a bell, but he designed the great French films of René Clair (La Proie du vent, An Italian Straw Hat, Les deux timides, Sous les toits de Paris, Le Million, À nous la liberté, and La Quatorze Juilliet) and Jacques Feyder (Gribiche [above], Carmen, Les Nouveaux Messieurs, Le Grand Jeu, Pensions Mimosas, and La Kermesse héroïque). He crossed paths with most of the major French Impressionist directors, sometimes in their post-Impressionist periods: Marcel L’Herbier (Feu Mathias Pascal, his masterpiece L’Argent, Le Mystère de la chambre jaune, and Le parfum de la dame en soi), Jean Epstein ( Les Aventures de Robert Macaire), and Abel Gance (Le fin du monde and Poliche). His credits include work with such French directors as Maurice Tourneur, Julien Duvivier, and Claude Autant-Lara.

Meerson was born in Russia and fled the Revolution. Making his way via Germany to Paris, he became the assistant to set designer Alberto Cavalcanti on Feu Mathias Pascal. That’s one of the five French films on a new Flicker Alley release, “From Moscow to Montreuil: The Russian Émigrés in Paris: 1920-1929.” Meerson’s illustrious career led him to England in the second half of the 1930s, where he designed several notable films, including Paul Czinner’s As You Like It, Clair’s Break the News, and Feyder’s Knight without Armour, as well as the classic The Scarlet Pimpernel. He died in 1938 at the young age of 38. (The best online source on Meerson is R. F. Cousins’ filmography, bibliography, and brief biography.) His influence lives on in the work of his most prominent student, Alexandre Trauner (Le jour se lève, among many others).

I begin with Meerson in order to stress how many important strands of film history come together in this very ambitious Flicker Alley set. It allows us to trace Meerson’s early years, from his first apprentice work, Feu Mathias Pascal, to his first and third projects for Feyder. That in itself would be enough to make this release notable, but the Albatros film studio in Paris during the 1920s hosted an amazing collection of talented people working in the cutting-edge styles of the era.

Here we also find three films starring the extraordinary Russian star Ivan Mosjoukine, known to most audiences by reputation only, and then only for the ephemeral Kuleshov experiment that used footage from an old film with Mosjoukine.  This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

This experiment is not known to survive. In it a close view his impassive face reputedly was edited together with shots of a dead woman, a bowl of soup, a small child, or perhaps other subjects, depending on which report you read. Spectators supposedly credited Mosjoukine with a marvelous performance, based on eyeline editing rather than any changes in his expression. We shall probably never know the exact form this experiment took and who saw it. I have to believe that the shots of Mosjoukine were inserted at wide intervals in a feature film, not strung together one right after the other, as makers of modern “reconstructions” of the experiment seem to assume. It’s much more interesting to watch Mosjoukine in the three very different performances presented here: Le Brasier Ardent, Kean, and Feu Mathias Pascal. His face is anything but impassive

We can also appreciate Belgian-born director Jacques Feyder, who had begun his feature-film career with L’Atlantide (1921) and Crainquebille (on our 10-best list for 1922) and then suffered a box-office disappointment with the charming, poignant Visages d’enfants, making two notable films for Albatros. Gribiche contains the first performance by Françoise Rosay, Feyder’s wife, who became one of the grandes dames of French cinema.

Most of all, however, this set makes a big step in showing us what happened after the Revolution to the most important Russian production company, that of Josef Ermolieff. The founder, as Lenny Borger points out in the highly informative booklet accompanying the set, had French connections from the start. Ermolieff “begin his career as a technical assistant at Pathé’s Moscow branch, and by 1912 had moved up through the ranks to become Pathé’s sales agent in Russia. On the verge of the war, he founded his own company and studio and gathered around him a core of artists and technicians who later would become the Russian film colony of Paris.”

The Russian work of the Ermolieff company was revealed to modern audiences in the groundbreaking retrospective of pre-Revolutionary Russian cinema presented at the La Giornate del Cinema Muto festival in Pordenone, Italy in 1989. The flood of hitherto unknown films included great melodramas starring Mosjoukine and other wonderful actors who made their way to Paris in the wake of the Revolution.

Ermolieff initially took his company to Yalta, where in 1918-19, they made several films. The next stop was Constantinople, and finally Paris via Marseilles. Ermolieff purchased the old Pathé studio in Montreuil-sous-Bois and set up filmmaking. The first film entirely produced there, Yakob Protazanov’s L’Angoissante aventure (1920) is not included in the Flicker Alley set. It does survive, however. I remember it as an entertaining film with the added attraction of having a story built around filmmaking. Perhaps someday that, too, can be made available on DVD. In the meantime, the five films in the set show the Russian emigrés gradually merging with the French filmmaking establishment of the day and supporting the work of some of the important Impressionist filmmakers.

Ermolieff himself decided to set up shop in Germany, selling the studio to two of his colleagues, Alexandre Kamenka and Noë Bloch. Renaming the firm Les Film Albatros, they brought it into the mainstream of French cinema.

Le brasier ardent (1923)

Mosjoukine directed two films, of which this is the second. It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

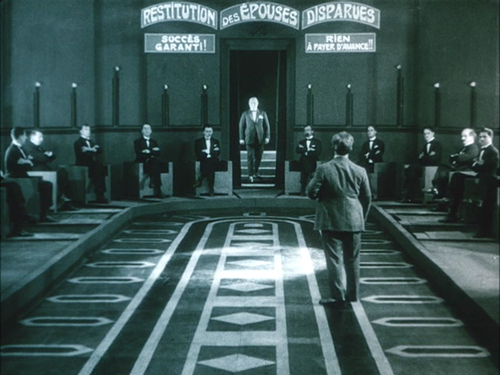

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

Kean (1923)

Le Brasier ardent has definite touches of the Impressionist style, but Alexandre Volkoff’s big-budget biopic Kean went further in that direction. I have to admit that it’s not one of my favorite Albatros films. Borger points out that, although it was a prestige picture in its day and quite successful, it has not worn well. The fault in part may lay in the source material, a play co-authored by Alexandre Dumas. Still, the film is notable for Mosjoukine’s anguished performance as the great Shakespearean actor. It also contains one of the most famous sequences of the Impressionist movement, where Kean gets drunk and dances frantically. Borger describes it: “The increasingly frenzied cutting that translate his state of mind was not there by chance: since the trade screenings of Abel Gance’s La Roue [also released by Flicker Alley] a few months prior to the shooting of Kean, rapid-cutting had become all the rage in French films–look at some of the major commercial pictures produced after La Roue’s release and you will find at least one obligatory explosion of rapid editing. But Volkoff was Gance’s best imitator.”

Feu Mathias Pascal (1925)

To quote myself from an article in the issue of Griffithiana devoted to the 1989 Pordenone retrospective:

These two films abruptly brought the Albatros group to the attention of the Impressionist directors and to supporters of the French avant-garde cinema. After having virtually ignored the Russian emigrés to this date, Cinéa published a long article on Le Brasier ardent and an interview with Mosjoukine; Kean received similar attention, and articles in Cinéa-Ciné pour tous and Cinémagazine appeared reguarly thereafter. After this point, Mosjoukine starred in films by the French Impressionists as well as those by emigré directors: Le Lion des Mogols, for Epstein, Feu Mathias Pascal, for L’Herbier, and, nearly, in Napoléon, for Gance.

For decades Feu Mathias Pascal was the most familiar of L’Herbier’s films, at least in the USA, where an abridged version was part of the Museum of Modern Art’s circulating 16mm collection. By now his L’Argent (1928) has probably eclipsed the earlier film’s reputation, at least in the eyes of critics, historians, and silent-film enthusiasts. Feu Mathias Pascal is a more approachable film, though, and would be a good choice for teaching French Impressionism.

Adapted from a novel by Pirandello, it stars Mosjoukine as a character described at the outset: “From childhood Mathias Pascal, a tormented dreamer, has cherished a fantastic hope to free himself to become his own Master!” This paves the way for the many dreams, visions, and heightened emotional states that will be conveyed by the superimpositions, selective focus, camera movements, and fast cutting beloved of the Impressionists.

Pascal finds himself in exactly the sort of situation he hates: tormented by his overbearing mother-in-law and by a wife too weak to side with him against her. His mother and infant daughter both die, and grief-stricken, he flees. A large win at a casino and a mistaken identification of the body of a suicide as Pascal lead him to seize the opportunity to begins a new life.

Mosjoukine left Albatros after this film, pursuing his stardom in big-budget exotic historical films and melodramas, including work in Hollywood and Germany, before his death in 1939 at the age of 49. This was also Michel Simon’s first significant film; he appears in an important supporting role.

Gribiche (1925)

Gribiche is a charming film built around the talents of the boy actor Jean Forest, whom Feyder had discovered for a small role in Crainquebille.

He plays Antoine, nicknamed “Gribiche,” the son of a war widow who struggles to support him and keep him in school. As the film opens, Gribiche returns the dropped purse of a rich woman, Mme. Maranet (Françoise Rosay), and refuses the proffered reward. Maranet, having a scientific interest in children’s welfare, on a whim offers to adopt him. Knowing that his mother is being courted by Philippe Gavary, whom she hopes to marry, Gribiche pretends to want the private education promised by Maranet, and off he goes to live in her modern mansion (Meerson’s design, see top). There he is raised by servants and tutors to a strict schedule, with no time allowed for play. Meanwhile, his mother becomes engaged to her suitor.

The story contains some implausibilities. During a fairground outing with his mother and Gavary (above), Gribiche overhears the two discussing a possible marriage, but both seem worried about Gribiche. There is a hint that the man won’t propose if he has to take on a stepson. This scene motivates the whole chain of affairs. Yet Gavary seems to like the boy, and when Gribiche gets fed up with his sterile life with Maranet and runs away, Gavary is concerned and willing to take him in with no hint of discord between him and the mother. Still, the story on the whole is carried by Forest’s ability to play for both humor and pathos, the beautiful Meerson settings, and the comic business with the tutors and servants. Rosay remarkably creates a character who is friendly and sympathetic yet lacks the deeper warmth that would allow her to raise a child.

For those not familiar with Feyder’s early work, this and the next item are musts. His three most important earlier films are available on DVD, so much of the director’s silent career, previously little known, is now accessible.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs (1928)

This is a Feyder work well worth getting to know. Moving beyond his films based on stories of innocents oppressed (Crainquebille, Visages d’enfants, and Gribiche), Feyder made an adaptation of Carmen (1926) that is competent but not exciting and Thérèse Raquin (1928), which to the best of my knowledge does not survive.

Les Nouveaux Messieurs was an adaptation of a different kind, one which Borger quite rightly compares to René Clair’s late silent comedies. Taken from a popular play of the 1925-26 season, it is a satirical comedy about Jacques Gaillac, an electrician who runs for public office and briefly ends up as labor minister in a leftist government. Along the way he courts Suzanne, a ballerina who is the mistress of the wealthy Count of Montoire-Grandpré. The Count is an older man who is patiently resigned to fighting off her occasional suitors, and we see him pulling political strings on the sly.