Archive for the 'National cinemas: Russia and USSR' Category

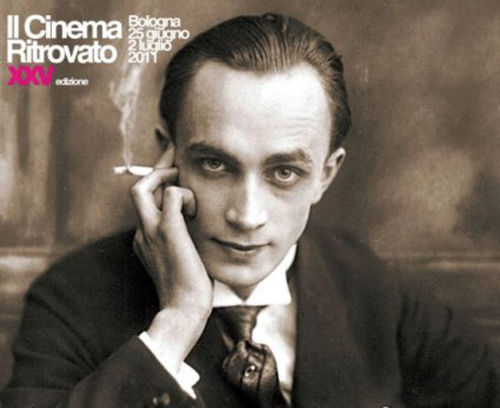

Solo in Bologna

Kristin here:

Two days before David and I were to set out for Bologna and its annual Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, back pain struck him. He decided not to go, and so our coverage this year will be briefer. I struggled to see as much as possible, but if anything, the program was even more packed than last year.

The auteurs

The main threads included four directors who are of historical interest. Raoul Walsh was the main attraction, with emphasis less on familiar classics like Roaring Twenties and White Heat and more on hard-to-see items like Me and My Gal and other early 1930s films. Lois Weber, the first important female director in American cinema, was represented with as complete a retrospective as possible, including fragments from features not otherwise extant. Jean Grémillon, one of the less famous French prestige directors during the 1930s and 1940s, was extensively represented. And there was Ivan Pyriev (or Pyr’ev, going by the program notes’ spelling), most famous as one of the main proponents of the “kholkoz [collective farm] musicals” of the last 1930s and 1940s.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

The Civil Servant (or The State Functionary, 1931) was a full-blown, skillful leap into Montage, with an prologue of trains coming into Moscow, shot with canted framings, low angles, and quick cuts with trains moving left, then right. The rest is a satire on bureaucracy within the national railroad system—ostensibly set during the Civil War but clearly a contemporary story. It’s broad in its humor, and it has the obvious typage in the choice of actors, the wide-angle lenses that the Montage filmmakers explored in the late 1920s, and other scenes of quick cutting with jarring reversals of directions.

Official dislike of The Civil Servant kept Pyriev from directing again for three years. Turning his back on Montage, he went to the other extreme, helping to develop the kholkoz (collective-farm) musical and making some of its liveliest, most entertaining, and most enthusiastic examples of that genre. His Traktoristi of 1939 was not shown during the festival, but one that I hadn’t seen, Swineherd and Shepherd (1941), is fully its equal. From the moment the film begins, with the camera madly tracking backward through a birch forest as the heroine runs full tilt after it, singing joyously to the masses of pigs that emerge from corrals and gallop along with her, the spectator realizes that this film will be exactly what one wants and expects from Pyriev.

A later entry in the genre, The Cossacks of the Kuban (1950), was even better, and I can see why it is Olaf’s favorite. The opening vistas of immense wheat fields, gradually moving to scenes with tiny figures and finally to ranks of harvesting machines and trucks achieves a genuine grandeur, aided considerably by the fact that by this point Pyriev is working in color. The story goes beyond the simple stock figures of some of the earlier musicals, with a stubborn Cossack who heads one collective farm nearly missing his chance at romance with a widow who heads a rival farm.

Overall, I like these films a little better than those of his more famous colleague in the creation of buoyant musicals, Grigori Alexandrov. Yet it has to be mentioned that there is a certain underlying unease in being entertained by films that created hugely idealized images of life on collective farms. In reality many peasants were starving, and few were working with such cheerful enthusiasm to increase production for the sake of the great Soviet state. One might rationalize this dissonance by thinking that Pyriev was perhaps making fun of his subject with over-the-top dialogue and musical numbers. Yet surely to many audiences at the time, this was escapist entertainment, and urban audiences may have had little sense of the blatant inaccuracy of the portrayals of the countryside.

Two more straightforward dramas, The Party Card (1936, below) and The District Secretary (1942), a war story, were more conventional Socialist Realist works, skillfully done but lacking the appeal of Pyriev’s lighter films.

It was sad to see the one post-Stalinist film from Pyriev’s late career, his adaptation of The Idiot (1958). A sumptuous production, again in color, it consisted almost entirely of overblown confrontations among characters. The actors shout all their lines at each other with almost no variation in the dramatic tone, with everything underlined by an amazingly intrusive musical score.

I saw only a few of the Walsh films, since they frequently conflicted with the Pyrievs and Grémillons and just about everything else on offer. To me, the director was a bit oversold. Peter von Bagh’s introduction to the catalog says, “Unjustly, Raoul Walsh, although blessed with so much cinephilic worship, is usually placed a few notches below his more revered colleagues Ford and Hawks. Now he will have a chance to be upgraded, in our continuing series featuring extensive screenings from Walsh’s silent period through his very rare early sound films.” Perhaps Walsh will go up a notch in people’s estimations—the screenings of his films were certainly very popular—but not, I think, the few notches it would take to place him alongside these two other masters. I enjoyed Me and My Gal, a rare 1932 comedy in which Spencer Tracy and a very young Joan Bennett adeptly exchange snappy patter, yet it occurred to me more than once during the screening that Twentieth Century (1934) is a much funnier film.

The Big Trail, shone in its original wide-screen Grandeur format on the giant Arlecchino screen, was better than I expected. Walsh was given enormous resources to tell the story of a large wagon train making its way to Oregon from the Mississippi. He showed off the crowds of wagons, cattle, and people by the simple expedient of raising the camera height so that most of the screen’s height became a tapestry of people stretching into the distance, all going about their business while the main dramatic action in the foreground occurred. This often involved a very young John Wayne, whose occasional awkward delivery of lines managed somehow to fit with his character.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Few of Walsh’s pre-1920s films survive, but those few were shown. I skipped the wonderful Regeneration, having seen it multiple times, but I caught The Mystery of the Hindu Image, notable mainly for Walsh’s own performance as the detective, and Pillars of Society, a somewhat stodgy adaptation of the Ibsen play.

I can’t say much about the Weber films, since they were consistently in conflict with screenings of films by the other main auteurs. I regret having skipped one Pyriev film, Six O’clock in the Evening after the War (1944) to see Shoes (1916), which had been touted as one of the director’s best. It proved a considerable disappointment, stuffed with expository intertitles that often simply described what we could already see from the action in the images. This may have been because Weber’s “discovery,” Mary McLaren, was so inexpressive. She almost constantly wore the same expression of resigned sadness at her family’s grinding poverty, varying it occasionally with a look of annoyance at her father’s shiftless behavior. I tried to steer people to The Blot, which is probably Weber’s masterpiece among the surviving films.

It was fairly easy to see most of the Grémillon titles, because a number of them were repeated in the course of the week. I enjoyed Maldone, which I had seen once long ago. Its story involves a runaway heir to a large estate who has run away as a young man and now, in late middle age, works on a canal barge. Infatuated with a beautiful gypsy and spurned by her, he returns to claim his inheritance, only to be disgusted by gentrified life. Like Pyriev, Grémillon came late to one of the commercial avant-garde movements of the 1920s, French Impressionism. He uses the subjective camera effects and the rhythmic editing in a straightforward way, with little of the flashiness of a L’Herbier or a Gance. Maldone and his subsequent film, Gardiens des phare (1929), shown at the festival in a tinted Japanese print, remind me of perhaps the best filmmaker of the Impressionist movement, Jean Epstein.

This legacy might logically have led Grémillon into the Poetic Realism of France in the 1930s. Unfortunately his first sound film, La petite Lise (1930), which might be said to fit into that tradition, was not shown. After seeing several of the films on offer this year, I still think it may be his masterpiece. (We talk about it briefly in the section on early sound cinema in Film History: An Introduction.) Though some might argue that he has at least one foot in that tradition, his work is perhaps closer to what the Cahiers du cinéma critics later dubbed the Cinema of Quality.

As for the others I caught: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (1938, dominated by Raimu as a successful merchant who is not all he seems), Remorques(1939-41, perhaps Grémillon’s best-known film, re-teaming the favorite French couple of the 1930s, Jean Gabin and Michele Morgan), and Pattes blanches (literally, “White putties,” 1948). I enjoyed them all, and yet there was no sense of discovering an overlooked genius. Best of the sound features for me was Pattes blanches, which tempered Grémillon’s taste for melodrama with a hint of surrealism. The obsessive young wastrel Maurice (played by a very young Michel Bouquet), the gamine hunchback maid who falls in love with the reclusive and menacing local nobleman, and the nobleman himself, invariably bizarrely clad in his white puttees, help give the film a fascination that the others, for me at least, lack.

The themes

There were other threads oriented by genre or topic or period. These I sampled when it was possible to insert them into my schedule. One of these was “After the Crash: Cinema and the 1929 Crisis,” which included an intriguing potpourri of documentaries and fiction films from several countries and political stances, from Borzage’s A Man’s Castle to two short films by Communist-leaning Slatan Dudow, director of Kuhle Wampe. Because of my interest in international cinema styles of the late 1920s and early 1930s, I went to Pál Fejös’s Sonnenstrahl (“Sun Rays,” 1933) was shown in the festival’s first time slot, 2:30 on Saturday afternoon. It thus competed with the first showing of the Grandeur version of The Big Trail and the first program of the “Cento anni fa” set of 96 films from 1912, but such is Bologna’s lavish scheduling.

Fejös, a Hungarian, made films in Hollywood, France, Denmark, Sweden, and a number of other countries. Sonnenstrahl, with its romance between German actor Gustav Fröhlich and French leading lady Annabella, is basically a reworking of the director’s best-known film, Lonesome (1928), with touches of 7th Heaven (Borzage, 1927), redone for the Depression era. It’s a pleasant enough piece, though not up to Fejös’s best work of the 1920s. Again, the program claims to too much for the filmmaker by saying that some historians consider him “as one of the cinema’s great poets, along with Murnau and Borzage.”

The Depression program also included a surprisingly good early sound film by Julien Duvivier, David Golder (1931, above). It’s the story of a wealthy businessman, played by Harry Baur, who discovers that his wife and daughter love him only for his money. How he could have lived this long with them without realizing this is perhaps a weakness in the plot, but from the start Duvivier showed a remarkable assurance in framing, cutting, and camera movement that was continually in evidence. Sets by the great Lazare Meerson also enhanced the style.

Baur also starred as Jean Valjean in Raymond Bernard’s 1934 three-part Les Misérables. I skipped the screenings, since the film is available in a Criterion boxed set (along with Bernard’s remarkable 1932 anti-war film Wooden Crosses). The Bernard film was part of the “Ritrovati and Restaurati” thread. The presence of Baur in both David Golder and Les Misérables led to the Depression and Ritorvati threads to weave together to produce a third: “Homage to Harry Baur.”

The only other entry in this brief thematic collection was Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (1933), the third film based on a novel by Georges Simenon. Baur stars as Commissioner Maigret, and Valery Inkijinoff (known largely as the hero of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia/The Heir of Ghengis Khan, though he acted in numerous other films as well) plays the doomed, obsessive villain, Radek. The film is not as accomplished as David Golder, but it’s an entertaining little thriller with some novel twists. Early in the film the murder is revealed, and we know from the start the Radek committed it. The duel between him and Maigret becomes the focus of the action. Moreover, the very first scene introduces a thoroughly unlikeable fellow who initially seems to be the villain, a womanizing cad who lives by gambling and other unsavory activities, yet who himself eventually comes to be tormented and threatened by Radek.

Another intriguing thread was “Japan Speaks Out! The First Talkies from the Land of the Rising Sun.” Ordinarily I would have tried to see most of these, but again they conflicted with the auteur threads I was trying to follow. I did make it a point to see Mizoguchi’s first sound film, Hometown (1930, above), since it’s one of the hardest to see. A part talkie built around a famous Japanese tenor and opera singer, it was more an historical curiosity than a satisfying film. I reluctantly skipped Heinosuke Gosho’s delightful Madame and Wife (aka The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine), the first really successful Japanese talkie, having seen it a number of times. On David’s and Tony Raynes’ advice, I caught Yasujiro Shimazu’s First Steps Ashore, a romantic tale inspired by Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. It didn’t quite match the original (as what could?) but was an entertaining tale well acted by the two leads. The first frame below reflects something of the style of Docks of New York, but the second, more typical of the film, is pure Shochiku.

The organizers of Il Cinema Ritrovato have declared that they will continue to show films on 35mm as long as possible. Most of the screenings that I attended were indeed on film. There’s no doubt that the move to digital restoration became dramatically more apparent this year. Nearly all of the 10 pm screenings on the Piazza Maggiore were digital copies, including Lawrence of Arabia, Lola, La grande illusion, and Prix de beauté. David and I don’t usually go to these screenings, since we invariably want to see films in the 9 or 9:30 AM time slots and don’t want to fall asleep during them. But I did catch two digital restorations shown earlier in the evening in the Arlecchino.

The first, Voyage to Italy, was flawless and sharp—perhaps a little too sharp. I liked the film much better than the first time I saw it, maybe because I understood better the claims that are made for it as a forerunner of the art cinema of the 1960s, with the aimless, confused couple presaging the characters of directors like Antonioni.

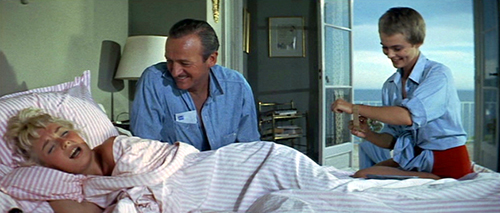

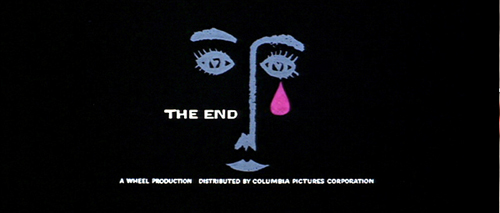

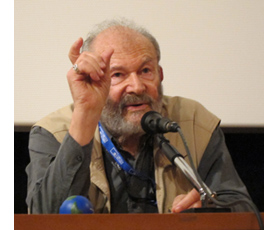

Perhaps the high point of my week, though, was an entry in an ongoing thread at the festival, “Searching for Colour in Films.” There were many films in this category, which was broken down into the silent and sound eras. Bonjour Tristesse may well be my favorite Otto Preminger film. Our old friend Grover Crisp (above, with interpreter) returned to Bologna to introduce it in a digital restoration, but one which, he assured us, retained the grain of the original film. It was certainly a beautiful copy and looked great on the Arlecchino screen. (The frames at the top and bottom of this entry were taken from a 35mm copy, not a DVD or the new restoration.)

Il Cinema Ritrovato grows more popular each year. A number of our friends from other festivals and alumni of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s film studies program attended for the first time and vowed to return. Perhaps a sign that the event is gaining real prominence internationally was the fact that Indiewire columnist Meredith Brody also made her first visit. She conveys the impressions of a newbie in a series of posts: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. For many images of the festival guests and screenings, see the official website.

David analyzes one Hitchcock-like scene in The Party Card in his On the History of Film Style.

July 9: Thanks to Ivo Blom for correcting my spelling of Harry Baur’s name.

Bringing to book

Artists and Models.

Blushing from Bryce Renninger’s generous article about us and the new edition of Film Art can’t keep us from offering another of our occasional entries devoted to new books we like. Get ready for lots of peekaboo links.

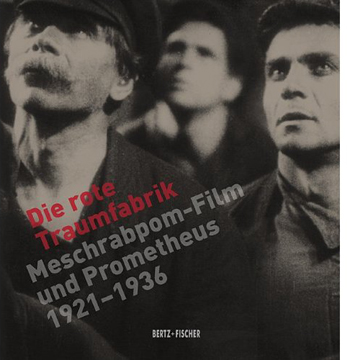

The rise of the Soviet Montage film movement of the 1920s and western countries’ knowledge of those films came about largely because of Germany. After pre-revolutionary film companies fled the Soviet Union, taking much of the country’s film equipment with

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

There was a direct link between Soviet and German socialist film production and distribution that is too little-known today. In 1921, Willi Münzenberg forms the Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (the IAH, known in Russia as Meschrabpom), based in Berlin. In 1924, the organization founded a film studio in Moscow, Rus. A year later, a sister company, Prometheus, was formed in Berlin. Both produced films, and they cooperated in distributing each other’s output.

Meschrabpom-Russ produced many of the familair Soviet classics: early on, Polikuschka and Aelita, and later the films of Pudovkin (including Mother and The End of St. Petersburg) and Boris Barnet (including Miss Mend and House on Trubnoya). Prometheus produced films highly influenced by the Soviet exports, both in terms of style and subject matter. These included Leo Mittler and Albrech V. Blum’s Jenseits der Strasse, Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, and, mostly famously, Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwald’s Kuhle Wampe oder wem gehört die Welt.

Prometheus, not surprisingly, disappeared in 1933. Meschrabpom-Russ continued until 1936.

A retrospective at the Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin in 2012 has occasioned a comprehensive, beautifully designed catalogue, Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Promethueus 1921-1936. With numerous expert essays and beautifully reproduced illustrations, both in color and black and white, of posters, production photos, film frames, and documents, this is the definitive publication on the subject. Even those who don’t read German will be able to use the extensive filmography and the biographical entries on the directors and other people involved in the making of the films. The illustrations make this the perfect combination of academic study and coffee-table art book. (KT)

Closer to home, our friends have been very busy. From Leger Grindon, a deeply knowledgeable specialist in American film, comes Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. The prizefight movie isn’t usually discussed as a distinct genre, but after reading this comprehensive and subtle study, you’ll likely be convinced that it’s been remarkably important. While discussing movies as famous as Raging Bull and as little-known as Iron Man (no, not that one; this one comes from 1931), Leger also introduces you to the finer points of genre criticism. The way he traces basic plot structures, key iconography, and historical patterns of change is a model of how thinking in genre terms can illuminate individual films.

Then there’s Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife goes beyond the usual recounting of peculiar, often lewd gag moments to treat Tashlin as not only a gifted director but a representative figure in 1940s-1950s American cinema. Ethan traces how Tashlin became a program-picture director who never acquired the status of auteur, at least in the eyes of the studio system. The book situates Tashlin in the context of the Hollywood industry, both the cartoon shops (Tashlin did animation work for both Disney and Warners, among others) and the live-action production units. There’s as well a fascinating chapter on Tashlin’s influence on directors as different as Joe Dante and Jean-Luc Godard, who coined the adjective “Tashlinesque.” A blend of critical analysis, cultural commentary, and industry history, Tashlinesque is surely the definitive book on this cheerfully dirty-minded moviemaker. Ethan maintains a lively blog here.

Not strictly about cinema, but a book that’s indispensible for film researchers, is James Cortada’s History Hunting: A Guide for Fellow Adventurers. A founding member of the Irvington Way Institute, Jim is at once an IT guru, a historian of computer technology, and a scholar of Spanish history, particularly of the Civil War. History Hunting, the fruit of forty years of spelunking in archives, museums, and the world at large, is an enjoyable handbook on doing historical research. It ranges from help with genealogy (case study: the colorful Cortadas, from Spain to the US) to suggestions about how to frame a doctoral thesis. Jim reminds us that the historian must turn into an archivist: the materials you collect are documents for future historians to use. You are, to use the new buzzword, a curator. Jim provides a welter of practical suggestions along with his own tales of the hunt. Jim devotes part of a chapter to Kristin and me, which just goes to show his impeccable taste in neighbors.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

One of the most original aspects of Writing in Pictures is Joe’s emphasis on adaptation. This is sensible because (a) a great many films are adapted from other sources (today, even comic books); (b) a professional screenwriter is often called upon to reshape an earlier script draft by another writer; and (c) adapting a preexisting source swiftly gets the novice screenwriter thinking about the relative strengths of verbal and visual storytelling. Joe takes us through the script-building process step by step, each time reworking London’s story “To Build a Fire.” Somewhat like the European “conservatory” approach to film education, McBride’s emphasis on organic interaction with classic traditions is something new, even radical, in the world of American screenplay education.

Then there’s Film and Risk, edited by the boundlessly prolific and enthusiastic Mette Hjort. Probably the most conceptually bold cinema book of the year, it assembles several scholars and filmmakers to assess how films and filmmakers deal with risk. The subject is of course broad. There’s risk in performance; risk in breaking stylistic boundaries; risk within film institutions (such as producing); risk in social and political contexts such as facing censorship; environmental risks, as in the costs that filmmaking exacts from the natural world; and even the risks of viewing movies—exposing yourself to horrifying or depressing stories and images. Film scholars like Hjort, Paisley Livingston, and Jinhee Choi mingle with film producers and industry observers to reflect on how cinema takes chances.

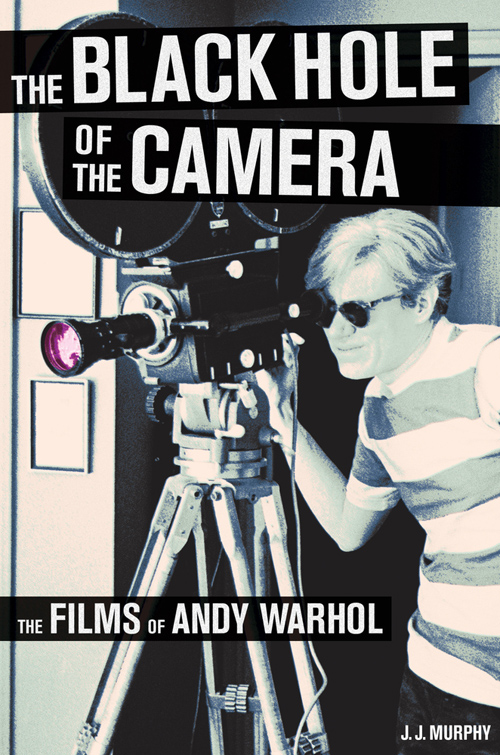

Our colleague J. J. Murphy has been researching and teaching the films of Andy Warhol for years, and today–literally, today–his monograph The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol comes out from the University of California Press. This is the most comprehensive, in-depth study of Warhol’s filmmaking that has ever been published, and of course a must-have for anyone interested in experimental film or the American art scene.

The ideas are fresh, especially the explorations of Warhol’s debt to psychodrama. At the same time, The Black Hole of the Camera clears away many misconceptions about Warhol (no, Sleep and Empire are not single-shot films) while also offering detailed information about and analysis of little-known stunners like Outer and Inner Space. There are several pages of color frames, which remind you that Warhol was as good at color as Tashlin was. JJ maintains a remarkable blog on independent cinema and is a leading figure in the Screenwriting Research Network.

Not a book, but a publication of great value: Three major researchers have collaborated on a cogent, nontechnical review of experimental investigations into film perception. All of the authors have had face time on this site. Dan Levin has executed breakthrough experiments on “change blindness”–how we miss discontinuities and anomalies in everyday life. (On another dimension, Dan’s film Filthy Theatre is coming up at our Wisconsin Film Festival.) James Cutting, a venerable figure in visual perception research, has ranged across many key areas in his consideration of cinema. He also wrote a wonderful book, available free here, on Impressionist painting. And Tim Smith, virtuoso eye-tracker, is author of one of our all-time most popular blog entries, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.”

With three top talents, you’d expect the collaborative paper to be a triumph of synthesis, and so it is. It supplies the best case I know for why we cinephiles should welcome psychologists who test the ways we watch movies. It should be required reading in every film theory course in the land. Access to the published paper requires a purchase or a library subscription, but you can read the preprint version here. Check in at Tim’s blog Continuity Boy for plenty of videos exploring his research (DB).

Finally, we’re sometimes asked why we don’t allow comments on our blog. The simple answer is that we’re not nearly as good at responding to comments as John Cleese is.

The cover of Joe McBride’s book pictured above is from the Faber & Faber edition, which makes a better still than the US edition from Vintage. Same good stuff inside, though.

Scriptography

Hollywood screenwriters at work, according to Boy Meets Girl (1938).

It’s not every conference that opens a morning session by asking the men in the audience to take off their underwear.

But I anticipate.

Last weekend I was a guest of the Screenwriting Resource Network’s fourth annual Screenwriting Research Conference in Brussels. I think that a hell of a time was had by all, and I learned quite a bit, including some reasons why people are interested in screenplays.

Schmucks with Underwoods

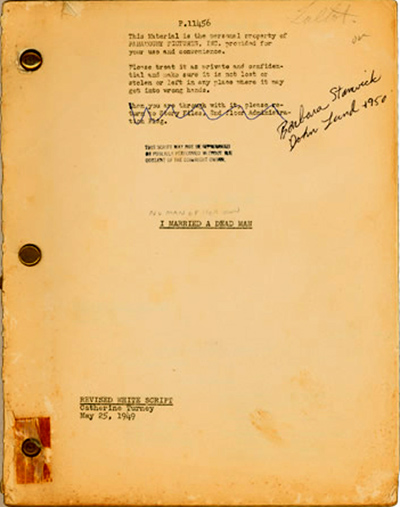

Catherine Turney script for No Man of Her Own (1950).

In my youth, there seemed to be a solemn pact among my peers that we would never study certain areas: censorship, audiences, adaptation (novels into film, particularly), and screenwriting. An earlier generation had, through patient labor, shown decisively that these subjects were dead boring. We, on the other hand, were fired by notions of the director as auteur, and indifferent to what were called “literary” and “sociological” approaches to film. So we triumphantly turned toward The Text—that is, the finished movie.

Things have changed since then. Yet there are still tempting reasons to consider the study of screenwriting a nonstarter if you’re interested in cinema as an art. If you think of the finished film as the achieved artwork, then study of screenplay drafts risks seeming irrelevant. Whatever the screenwriter(s) intended seems irrelevant to the result. So what if six or more screenwriters labored over Tootsie? The movie stands or falls by what we see onscreen.

This was the view presented in Jean-Claude Carrière’s three talks to our group. He suggested that the screenplay is destined to become landfill, and rightly so. It’s like the caterpillar that becomes a butterfly. Once the film has been made, the script has no intrinsic value.

Someone might say, “Wait! We study a painter’s sketches, a novelist’s drafts, or a composer’s early scores. These materials can contribute to understanding the finished work, and sometimes they have an artistic value of their own.” The problem is that in these arts, the preparatory materials are in the same medium as the result. But a script can’t count as a version of the film because prose can’t adequately specify the audiovisual texture of a movie. It’s commonly thought, plausibly, that giving the same script to two directors would result in significantly different films. So the script is at best a series of suggestions for filming, not a sketchy version of the movie. Why not discard it when the film is done?

The study of screenwriting has probably also lain in the shadows because of the proliferation of screenwriting gurus and how-to manuals. Every American over the age of eighteen seems to be writing a screenplay; the Cable Guy who visited me last week was working on two. So all the seminars and advice books have arguably put thinking about screenplays rather close to the amateur-script racket.

Moreover, screenplay studies seem to be part of a broader, paradoxical development in academic film studies. Today scholars have more access to films than ever before, thanks to video, festivals, archives, and the internet. Yet many researchers prefer to talk about everything but the film. More and more scholars want to study just those subjects that my cohort considered dull or irrelevant: censorship and regulation, audiences (composition, demographics, critical reception, fandom), and preproduction factors (storyboards, scripts). In addition, many academics have turned to bigger thematic ideas like film and architecture, film and the city, film and modernity. These trends of research usually make only glancing reference to actual movies, mostly mining them for quick illustrative examples.

In sum, many academics have abandoned the study of film as an artistic medium that finds its embodiment in important works. To get to know particular films more intimately, you increasingly have to go to the Net, to writers like Jim Emerson, Adrian Martin, and other sensitive analytical critics. Talking about screenwriting can seem to be another way of avoiding coming to grips with the intrinsic power of movies.

You can probably tell that one side of me shares some of the biases I’ve listed. But when I remind myself that what people should study aren’t topics but questions, I cheer up quite a bit. For there are, I think, worthwhile questions to be asked about all these areas, screenwriting included. The Brussels event gave some good instances of resourceful, occasionally exciting research into them.

Based on my short acquaintance, most of the research questions seem trained on one of two broad areas: Screenwriting and The Screenplay.

In the trenches

Kinky & Cosy

Screenwriting can be thought of as a practice, a creative activity with both personal and social aspects. How, we might ask, do screenwriters or directors express themselves in the script? How does a media industry recruit, sustain, and reward screenwriters? What are the conventions and constraints at work in a particular screenwriting community?

Questions like this are somewhat familiar to me. When I wrote my first book, on Carl Dreyer, I had to examine his scripts (notably the unproduced Jesus of Nazareth), and that helped me understand his characteristic methods of researching and planning his films. Later, when I collaborated with Kristin and Janet Staiger on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I recognized a more institutional side of things. We can see from the films of the 1910s that filmmakers were cutting up the space in fresh ways. But this wasn’t a matter of directors simply winging it on the set. Kristin used published manuals and Janet used original screenplays to show that shot breakdowns were planned to a considerable degree before shooting. This habit made production more efficient and controllable.

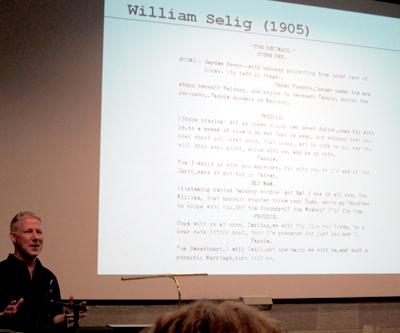

At the Brussels get-together, Steven Price offered further evidence of this sort, which displayed some of his research on early scenarios for Mack Sennett movies like Crooked to the End (1915). Interestingly, Steven found that sometimes the later version of a continuity script was more laconic than the initial one. Perhaps the gags, once spelled out in the first draft, could be left up to the actors. This is the sort of thing he identified as a “trace” of production practices.

A parallel of sorts emerged in Maria Belodubrovskaya’s paper on screenwriting under Stalin. The Soviets, admiring Hollywood efficiency, tried to come up with a similar system. But their efforts to produce films in bulk were blocked by a censorship apparatus bent on ideological correctness. No surprise there, I guess. But Masha showed convincingly that the very efforts to mimic Hollywood’s “assembly-line” system also discouraged authors from submitting scripts. The writers thought (like many of their LA counterparts) that such a setup denied them creative freedom. In addition, the prospect of story departments providing a stream of screenplays ran afoul of the tradition that gave the director control of the final draft. And the role of producer, as one who could steer the whole process, didn’t exist! So much for the Soviet Hollywood.

What about other media? Sara Zanatta traced out the process of creating Italian TV series. She reviewed some major formats (miniseries, original series, adaptations of foreign series) and then took us through the process of creating individual episodes. Interestingly, it seems that the Italian system, unlike US television, makes the director the boss of it all. Frédéric Zeimat explained how he gained entry to the local screenwriting community through his university education, including work in Luc Dardennes’ workshop at the Free University of Brussels. Eventually he came up with a script that won prizes. He is about to become a showrunner for a sitcom.

One of the most stimulating panels I heard considered the writing of graphic novels and animation. Richard Neupert explored how recent French animation sustained the tradition of individual authorship while still acceding to some international norms of moviemaking. The cartoonist Nix discussed how he faced new problems in transferring his three-panel comic strip Kinky & Cosy from print to television. TV demanded less written text, especially signs, so that the clips could be exported outside Belgium. More deeply, Nix had to rethink how to pace the action and leave a beat (say, two seconds) after the punchline.

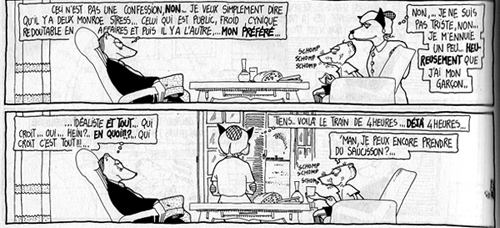

Pascal Lefèvre, one of Europe’s leading experts on comic art, provided a brisk, packed account of the history and practices of scriptwriting for Eurocomics. He described patterns of collaboration, format, and creative choice, placing special emphasis on comics as a spatial art different from cinema. His example was a page from Regis Franc’s ulta-widescreen album Le Café de la plage. Here’s a portion in which two periods of Monroe Stress’s life coexist in a single space. He muses as an adult while his childish self gobbles up food under the guidance of Mom.

Comics space can also change abruptly, as when a window appears in second panel.

Other papers presented less institutionally fixed, more personal versions of screenwriting as a practice. Kelley Conway’s lecture on Agnes Varda exploited unique access to the filmmaker’s notebooks, scrapbooks, and databases. Kelley showed how Varda conceived three of her documentaries by means of strict categorical structures that were then frayed by digressions born out of the material she shot.

Anna Sofia Rossholm provided something similar for Bergman. Out of the vast Bergman archive she quarried sixty “workbooks,” typically one for each film. Whereas Varda’s books were filled with cutouts and images, Bergman was a word man, treating the books as diaries that recorded “this secret I.” Anna Sofia proposed that in his jottings and planning, Bergman not only communed with himself (calling himself an idiot on occasion) but also explored patterns of doubling akin to those we find in the films. The workbooks evidently held a special place for him: he included their pages in films like Hour of the Wolf and Saraband.

David Lean might be thought of as working in between the Hollywood system and the more personal European milieu. Ian Macdonald suggested that one of Lean’s unfilmed projects sheds light on what he calls screenplay poetics. Macdonald seeks, I think, a principled method for studying the creative process. He does this by tracing how a screen idea is transformed in a series of documents generated by the creative team. The process, he points out, is governed by the participants’ various conceptual frameworks. For Nostromo, Lean solicited two screenwriters and oversaw their rather different versions of the novel. Ian showed that Lean seems to have found solutions to adapting the book by fitting it to the three-act structure advocated by Hollywood artisans, a concrete case of a filmmaker accepting a fresh “poetics” or set of creative constraints.

All of these inquiries could lead to more general thoughts about the creative process in cinema. For some filmmakers, it’s a professional task, undertaken with full knowledge that problems and constraints will have to be dealt with. For others, such as Bergman and Varda, it’s obviously deeply personal, even autobiographical. Perhaps most intimate was the film discussed by Hester Joyce. New Zealand filmmaker Gaylene Preston based Home by Christmas (2010; above) partly on audiotape interviews with her father as he recalled his World War II experiences. Her script reconstructed her interviews with actors, then filled in scenes with documentary footage and scenes she imagined. It’s a family memoir on several levels: Preston’s daughter portrays her own grandmother.

The Screenplay: What is it?

Several of these probes into the creative process raise a more theoretical question. How should we best conceive of the screenplay? As a blueprint? A recipe? An outline? These labels all suggest something disposable preliminary to the real thing, the movie. But why can’t we think of the screenplay as a freestanding object? After all, there are films without screenplays, but there are also screenplays—some written by distinguished authors—that were never made into films. And some of these, like Pinter’s Proust screenplay, are read for their own sake.

In cases like this, should we consider the screenplay a literary genre? And if the screenplay for an unproduced film can be considered a discrete object, what stops us from treating a filmed script in exactly the same way? Moreover, why even speak of a single screenplay, when we know that most commercial films at least go through several drafts? Can’t we consider each one an independent literary text? We’re now far from Carrière’s idea that the script finds its consummation in the finished film and as a piece of writing it should wind up in the ashcan.

And not all screenplays are literary texts. The scrapbooks and databases that Varda accumulates are works of visual art, collages or mixed-media assemblages. Are these merely drafts of the film, or do they have an independent existence or value? We seem to be asking the sort of question that Ted Nannicelli poses in his Ph. D. dissertation. Is there an ontology of the screenplay?

Take a concrete example. Ann Igelstrom’s paper, “Narration in the Screenplay Text,” asked how literary techniques are deployed in the screenplay. When a passage in the script for Before Sunset begins, “We see…,” who exactly is this we? Ann argued that traditional narrative concepts involving the source of the narration, the implied author and implied reader, and the rhetoric of telling can illuminate conventions of screenwriting. Here the screenplay seems definitely a literary text.

In his keynote address, “The Screenplay: An Accelerated Critical History,” Steven Price (above) declared a more abstract interest in the ontology of the screenplay but proposed that there was no clear-cut way of defining it. Historically, the screenplay takes many forms. Steven pointed out that even in Hollywood, there were many alternative formats, ranging from detailed breakdowns to the “master-scene” method (the option that didn’t specify shots or camera positions). And conceptually, the screenplay carried traces of its original production purposes, as well as other constellations of meaning. (Mack Sennett scripts seem to him part of a Sadean tradition of dehumanized, repetitive recombination.) So if there is a distinctive mode of being of the screenplay, outside of its role in production, it will turn out to be a messy one.

Envoi

J. J. Murphy presents a paper on Ronald Tavel. Photo courtesy Richard Neupert.

If we conceive studies of screenplay and screenwriting as revolving around specific research questions, those of us interested in film as art can learn a lot. If our interests are in film history, researchers can show how organizations of production and individual choices by screenwriters/directors can shape the final product. For those of us interested in more theoretical explorations, asking about the nature and “mode of being” of the screenplay can’t help but make us think more about the ontology of cinema itself.

And if we want to know films more intimately, being aware of the creative choices that were made by the filmmakers throws a spotlight on aspects of the film we might otherwise not notice. It’s all very well to say we’ll examine the film “in itself,” but our attention is invariably selective. Knowledge of behind-the-scenes decisions can sharpen our awareness of artistic matters. Anna Sofia’s research on Bergman, like Marja-Riitta Koivumäki’s paper on Tarkovsky’s screenplay for My Name Is Ivan, activates parts of the film for special notice.

Because there were split sessions at the conference, and because I was plagued by jet lag, I couldn’t attend every panel and talk. I regret missing papers I later heard were very fine, and I haven’t written up everything I heard. I haven’t sufficiently talked about screenwriting pedagogy, represented in papers like Lucien Georgescu’s dramatic appeal to rethink whether screenwriting should be taught in film schools, or Debbie Danielpour’s stimulating survey of her methods of teaching genre scripting. So this is just a small sample of what these folks are up to. But you can tell, I think, that they’re posing questions at a level of sophistication that my 1960s cohort couldn’t have envisioned. Despite what the cynics say, there is progress in academic work.

As for men’s underpants: All is explained here.

I’m grateful to conference organizers Ronald Geerts and Hugo Vercauteren for inviting me to speak at the gathering. I must also thank conference organizer and old friend Muriel Andrin, along with Dominique Nasta and their colleagues and students from the Arts du Spectacle Department at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. My friends at the Cinematek, Stef and Bart and Hilde, helped me with my PowerPoint. Thanks as well to the Universitaire Associatie Brussel (Vrije Universiteit Brussel / Rits-Erasmushogeschool Brussel) and Associatie KULeuven (MAD-Faculty / Sint Lukas Brussel). A high point of the event was the visit to La Fleur en Papier Doré. Special thanks to Gabrielle Claes for her heartfelt introduction to my talk, not to mention a delicious bucket of moules.

A founding document in the contemporary study of the screenplay is Claudia Sternberg’s Written for the Screen: The American Motion-Picture Screenplay as Text (Stauffenburg, 1997). Other books central to the conference cohort include Steven Maras’s Screenwriting: History, Theory, and Practice, Steven Price’s The Screenplay: Authorship, Theory and Criticism, J. J. Murphy’s Me and You and Memento and Fargo: How Independent Screenplays Work, and Jill Nelmes’s anthology Analysing the Screenplay, which includes many essays by members of the group. See also the affiliated Journal of Screenwriting.

For more information on the Screenwriting Research Network, go here. (Thanks to Ian Macdonald for the link.) The next conference will be held in Sydney, and the 2013 one will take place in Madison, Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 Sept 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

P.P.S. Thanks to Joonas Linkola for a spelling correction!

Coke does go through you pretty fast. Richard Neupert at a Coca-Cola machine that exploits a Brussels landmark.

More riches from Bologna

We’re still catching up with last week’s generous Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, the world’s premiere festival of restored and rediscovered films from all eras.

DB here:

O Segredo do corcunda (The Hunchback’s Secret, 1924) was more than a curiosity. Directed by the Italian Alberto Traversa, it was the first Brazilian feature screened abroad. It also has a documentary bent in that it shows a bit of what coffee farming was like in that era. The plot traces how the budding romance between a poor boy and the plantation owner’s daughter is blocked by the overseer Pedro, who actually killed the boy’s father.

The film illustrates penetration of Hollywood filming technique around the world. The linear plot includes a flashback explaining key motivation, a romantic subplot with helper characters, and a last-minute rescue built out of parallel editing. Scenes are filmed and cut according to continuity principles, with eyeline matches and angled changes of setup. There is even a split-screen delirium sequence.

Yet the film was out of step with Hollywood in one respect: the proportion of titles, especially dialogue titles. O Segredo do Corcunda has a lot of intertitles; they make up 22% of all its 518 or so shots. Somewhat similar proportions can be found in the mid-1920s in Hollywood, as Upstream and Cradle Snatchers indicate. But what’s different is the proportion of dialogue titles to expository ones. Most Hollywood films of the period have a very small proportion of expository titles, usually no more than 15% of all titles, and often much less. Fazil, discussed in an earlier entry, has 118 dialogue titles and only seven expository ones. But in O Segredo the 65 dialogue titles comprise 57% of all titles, leaving the 49 dialogue titles to make up the difference.

Why does this matter? In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I argued that American generally tend to favor methods that let the story seem to tell itself. Although an early silent feature might have many expository titles, in the late 1910s and the early 1920s, films began minimizing expository titles and letting dialogue carry the action. By the 1920s a US film would have relatively few expository titles. The pattern is visible across a film as well, with expository titles most common in the opening scenes but diminishing as the plot proceeds. In Segredo, not only do expository titles do more work, they’re spread out pretty evenly across the film. An external narrational authority is there from start to finish.

I suspect that the method of fading external authority is an identifying mark of American silent film and is rarer in other cinematic traditions. If that hunch is right, we can ask: Why did other countries persist in using expository titles so much? Matters for further research!

Polustanok (A Small Station).

Boris Barnet started out as one of Lev Kuleshov’s circle, and he became a well-established director. Not as famous as the Big Three (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko) or even Kuleshov, Barnet directed charming comedies like The Girl with the Hat Box (1927) and The House on Trubnoi Square (1928) and heartfelt dramas warmed by music, such as By the Bluest of Seas (1935). But many of his later films are unknown to me. I couldn’t catch all the titles in the Barnet retrospective, but the two features and one short I saw convinced me of his gifts.

Those gifts come off as gentle and genial in the wartime feature A Good Lad (Slavny Maly, 1942). A French pilot’s plane is downed in a Russian forest, where a resistance group is hiding out and forming its own little community. Living under the imminent threat of discovery doesn’t forestall songs, romantic affairs, and mistakes born of the language gap. (“I love you.” “I don’t understand.” “I don’t understand.”) Somber notes are struck when the village poet strides along singing patriotic tunes set to Borodin’s melodies, and soon the German soldiers are finding some partisans to threaten. With the villagers’ help the plane is repaired and soars into the sky to engage the enemy. The film seems to take place in an otherworldly realm, floating between an idyll and a battlefront drama.

Twenty years later Barnet could indulge in a more relaxed pastoral. Polustanok (1963) is variously known as Whistle Stop or A Small Station. A Moscow scientist goes on a painting vacation to the countryside. He settles into a collective farm where many painters have come before and winds up in a shed that is underfurnished (the chickens have to be shooed out) and overdecorated (the walls are covered with graphic inspirations). With something of the episodic structure of M. Hulot’s Holiday (though without its rigorous underlying timetable, at least to my eye), A Small Station rings variations on the fish-out-of-water situation of Pavel Pavlovich. He makes friends with a local delinquent, the party man, and cute girls. He even gets some support from the grumpy farm lady who has been painted many times and in many styles, some surprisingly unofficial in those Krushchev years. After Pavel sets painting aside, he and the delinquent build a brick stove for his shed. He signs it as if it were a work of art. He can return to Moscow reinvigorated, and as so often happens in films like this (Local Hero comes to mind), the departure is bittersweet.

Barnet’s light touch was nowhere in evidence in the long-unavailable short Priceless Head (A Bestsenaya golova, 1942). On every corner of an occupied Polish city, the Nazis have mounted a reward poster for a wanted partisan. He realizes he’s trapped, and meeting a penniless woman unable to feed her sick child, he offers to let her turn him in. This impossible choice is rendered in precisely controlled drama, with not a wasted shot or false note. Priceless Head shows that Barnet was an outstanding dramatic director, as well as Soviet cinema’s most unassuming lyricist.

Underground New York.

What would a trip to Bologna be without a foray into the 1910s? Kristin will have a lot to say about the biggest discovery, the consistent excellence of Alberto Capellani, so I’ll contribute a mite on the things I enjoyed. Of course I tracked the Feuillades. Roman Orgy (1911) was fairly tame, even allowing for a climax of Christians crunched by lions in the arena. Bébé est neurasthénique (1911) was shamelessly silly, with the little rascal pulling dishes off the table and then escaping punishment by feigning illness. His gift for rolling his eyes back into his head proved to be as funny on the tenth instance as on the first. But the most peculiar Feuillade entry was a sort of satiric PR response to Les Vampires. Lagourdette Gentleman Cambrioleur (1916) shows Musidora, no longer Irma Vep, absorbed in reading the novelization of Les Vampires. Marcel Levesque decides to woo her by pretending to be a debonair thief, so he convinces his valet and cook to pose as wealthy opera patrons. He’ll then display his skills by robbing them in front of Musidora. The two-reeler accepts, in a mocking spirit, the charge from bluenoses that sensational stuff on the screen only encourages crime.

Lagourdette has its nice points, notably its tendency to supply very large close-ups of its principals. (Who knew that Musidora had freckles?) This technique, almost absent from Feuillade’s features of the period, may have been an adaptation to the star-driven nature of the product. As Annette Förster noted in her introduction, the film involved a sort of product placement, and Gaumont’s stars, no less than its literary spinoffs, were branded items. The movie is minor Feuillade but significant in showing that as early as 1916, filmmakers were seeking synergy.

Mauritz Stiller began directing in 1912, and through 1914 he turned out some 20 films. All have been assumed lost, but one surfaced in Poland a few years ago. It was restored in 2011 by the Swedish Film Institute, so once more Ritrovato hosted a “second world premiere.” Gränsfolken (People of the Border aka The Border Feud, 1913) is derived from a Zola novel. A boy and a girl fall in love, but their families live on opposite sides of a border. For the girl’s father, loyalty to country comes before all else, and so he tries to block the marriage. Nonetheless the couple unite, but they face a dilemma when the two countries plunge into war. Will the young man fight for his old homeland or his new one? And will his ferocious brother kill him as a traitor?

Stiller had mastered the tableau style of the 1910s. Although nothing in the film displays Victor Sjöström’s virtuosity in staging, Stiller gets a lot of mileage out of the two families’ densely furnished parlors. Every inch of the frame is used at some time or another; a figure lying on a tall bed can roll into view in the upper left corner of the shot. The exteriors are picturesque and often framed geometrically. I need to see Gränsfolken again to do justice to its visuals, but the fairly restrained playing and the emotional intensity of the situation prefigure what would become signature elements in Stiller’s style in work like the Thomas Graal comedies and of course Herr Arne’s Treasure (1919).

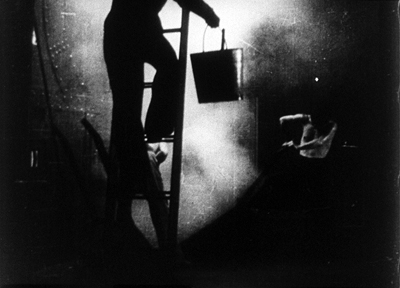

Jumping far ahead to the 1960s, it was a pleasure to see Gideon Bachmann’s Underground New York. Shot in 1967, it treats protests against the Vietnam War as of a piece with the avant-garde film scene. Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas, the Kuchars, Bruce Conner, and other legendary figures are captured in quick, telling portraits. Andy Warhol confides that acting in his film involves not performance but “faking it.” There are many lively moments—Conner dancing in pegged pants, Mekas tearing up company checkbooks—and enough nudity to suggest that new filmmaking and political protest were tied to erotic liberation.

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Over eight hundred hours of those meetings have been preserved in Bachmann’s audio archive, Vox Humana—The Voice Bank. The model for Bachmann has always been not the interview, with its predictable questions and stale answers, but the conversation, “just friends talking.” Bachmann, a straightforward and serious man, was forty when he made Underground New York, and he retains the mature lucidity on display in his comments in that film—and in his film criticism, which I remember reading with pleasure in Film Quarterly in the 1960s. We’re likely to get an earful of his archive, for Criterion has already signed up the North American rights to the Vox Humana collection.

KT here:

Given the great abundance of films at this year’s festival—some might say an overabundance—I singled out out three threads to concentrate on. I resolutely ignored the others unless I could somehow fit a film in here and there. Naturally I chose the second part of the Albert Capellani retrospective that began last year; I wrote about the 2010 season here and will do a follow-up soon. I also chose the 1911 “Cento Anni Fa” programs, since, as usual, the festival presented films from exactly one hundred years ago. Not surprisingly, the most interesting among these were by Feuillade, which David covers above, and Capellani. Finally, since I have a particular interest in Weimar cinema, I stuck with the “Conrad Veidt, From Caligari to Casablanca” retrospective.

The title refers to what are probably Veidt’s two most famous roles, as the somnambulist Cesare in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) and his final performance, as the Nazi Major Strasser, in Casablanca (1942). But presumably on the assumption that just about everyone knows these two films well, Il Cinema Ritrovato didn’t show either one. Instead, the program successfully assembled a group of lesser-known Veidt performances. Despite the fact that I’ve seen a lot of Veidt’s films from the 1910s and 1920s, almost all the items on offer were new to me. The selection seemed designed to display the considerable range of an actor often identified with villainous roles, like his portrayals of Nazis in the 1940s, or downright demonic, like Ivan the Terrible in Waxworks.

Almost none of the films in the program were newly discovered or restored. Most were drawn from existing prints held by various archives. The Wandering Jew, for example, was a beautiful print from the National Film and Television Archive, but it was full of splices, often with whole lines of dialogue missing. The exception was The Thief of Bagdad, a newly restored version shown as one of the evening screenings in the Piazza Maggiore. Not having the stamina that we once had for nearly round-the-clock film viewing, David and I missed all of those. I also passed up the familiar Waxworks (1924, Paul Leni), which I gather was shown in the same dark, indistinct version that has been circulating for years. It’s a film ripe for restoration, but perhaps no better material survives. That would be a pity, since it’s the one film that three of the main Expressionist actors, Veidt, Werner Krauss, and Emil Jannings appeared in together. Leni is also an interesting director, as well as a set designer; perhaps a retrospective of his largely unknown body of work could be arranged someday.

Apart from these, the program pulled together an admirable selection of films. The earliest, Dida Ibsens Geschichte (“Dida Ibsen’s Story,” 1918, Richard Oswald), was a sequel to the original version of Das Tagebuch einer Verlornenen, later remade in 1929 by G. W. Pabst with Louise Brooks. Veidt features relatively little in Dida Ibsen, playing a rich man who takes Dida as his mistress. The film is stolen by Werner Krauss, however, playing a highly eccentric man who forces Dida to marry him and then terrorizes her and their little daughter. Their home is crammed with what appear to be the exotic souvenirs of the husband’s adventures, including Asian furnishings and curios, as well as a parrot, crocodile, and lively python. Krauss carried the latter curled around his body much of the time. Indeed, where else could one see two snake-carrying villains in a single week? Three days later I watched Burl Ives sporting a cottonmouth moccasin in Nicholas Ray’s Wind across the Everglades, a film from the color series that I managed to fit into my schedule.

Veidt’s demonic roles are well represented here not only by Waxworks but also by the 1922 historical epic Lucrezia Borgia (also directed by the prolific Richard Oswald). I had expected the latter to be the usual stodgy historical drama, but it was livelier and more enjoyable than I had expected. Veidt plays the ruthless Cesare Borzia, lusting after his sister Lucrezia and scheming against her repeatedly until he leads a suicidal attack on the fort where her husband is defending her. The fort itself is an immense, lumpy set of the kind common in German epics of the 1920s, That, along with the huge armies of extras, suggests that this was one of the biggest-budget films prior to Metropolis.

Veidt was more versatile than such roles would suggest, however. He often played intense, suffering young men, as in one of F. W. Murnau’s earliest surviving films, Die Gang in der Nacht (1920, not, as in the catalogue, 1922). Veidt plays a supporting role as a mysterious, spiritual young painter who has been blinded. His more cheerful side was in evidence in the wonderful musical The Congress Dances (19331, Eric Charell); there as the confidently scheming Metternich he smilingly relishes eavesdropping on officials and politicians and reading their sealed letters with a contraption involving a bright lamp and magnifying lenses. He plays a Prussian military hero in Die letzte Kompagnie (1930, Kurt—later Curtis—Bernhardt), an early talkie shown in what appeared to be an English-language version, part dubbed, part redone with the actors speaking English.

Veidt’s ability to play both sympathetic and dastardly characters was shown off in the final two offerings, scheduled back to back, in both of which he plays diametrically opposed brothers: Die Brüder Schellenberg (1926, Karl Grune) and Nazi Agent (1942, Jules Dassin). Seeing the two films juxtaposed was odd. In each one, the evil brother is played by Veidt as he usually looked, with dark hair slicked back from his face, while the virtuous brother is gray-haired, reserved, with a little goatee (below). One has to suspect that Dassin saw the earlier film, and in fact Die Brüder Schellenberg was screened at the festival in an American print entitled Two Brothers.

The Mosfilm site offers some Barnet titles for downloading, without subtitles and for a fee. The short list includes A Small Station. The opening twelve minutes, with subtitles, can be found on YouTube. A Good Lad is available here, for free, without subtitles.

For a lovingly compiled fan site, see The Conrad Veidt Society, but beware the Wikipedia entry.

[Thanks to Armin Jäger for correcting my mistake on the date for The Congress Dances.]

Conrad Veidt and Conrad Veidt in Nazi Agent.