Archive for the 'National cinemas: Russia and USSR' Category

More revelations of film history on DVD

The Great Consoler.

Kristin here:

Upon returning from Vancouver, we found the usual mountain of mail awaiting us. Among the bills and ads were some very welcome items: a new flock of DVDs of considerable historical interest.

A German Documentary on Veit Harlan

After Leni Reifenstahl, Veit Harlan is the most famous of the directors who made films for the Nazi regime. He made Jud Süss, which is the only non-Riefenstahl Nazi film you might have seen apart from Triumph of the Will and (if you think it’s Nazi propaganda) Olympia.

Now Felix Moeller has made a documentary film, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss (“In the Shadow of Jud Süss,” c. 100 minutes). It’s available on a German DVD from Edition Salzgeber and can be purchased from Amazon Germany. (Beware, it’s coded Region 2, so you’ll need a multi-region player.) It has English subtitles, a feature some European DVD makers wisely include, since they know that there are a lot of us out here with multi-regional players. A region 1 version will also be released in the U.S. on November 23 and is available for pre-orders on Amazon.

Harlan is a fascinating film, both in terms of its subject matter and its strategies. It starts out in a fairly conventional way, showing Harlan’s grave, and then drops a few brief clips from Jud Süss in among shots introducing some of the director’s descendants. He was married twice and had five children, who in turn had children, and there are nephews and nieces as well. At one point one granddaughter draws a family tree to help us out. (The small accompanying booklet has a “who’s who” feature with photos to help us keep the family members straight. This booklet is entirely in German.)

Much of the early part of the film is taken up with the story of Harlan’s career making films for the Nazis, being found innocent after two trials in the post-war era, and continuing his filmmaking into the 1950s. A nicely ironic comparison is made between Harlan’s “I was just following orders” defense and the identical defense that Süss makes during his trial scene in the film.

Initially the relatives seem to be present in part to provide information and in part to comment on Harlan’s life. Later in the film, however, we realize that “the shadow of Jud Süss” falls over them as well, and they have reacted in a wide variety of ways. A expository motif that runs through the film is a visit paid by several of the younger family members to an exhibition on the film (see below), where they (and we) are shown documents and clips.

One son, Thomas, denounced his father publicly and for decades sought evidence to convict Nazi war criminals. (Thomas Harlan died last weekend; see David Hudson’s obituary here.) Kristian Harlan and Maria Körber, his half-brother and half-sister, criticize him for not keeping his attitudes toward his father in the family. Thomas’ daughter Alice works as a physiotherapist in Paris and realizes she does not share her grandfather’s guilt–yet she worries about some sort inherited taint. Another son, Caspar, became an anti-nuclear activist, along with his wife and three daughters. Two sisters, Maria Körber and Susanne Körber both married Jews, almost as if to make amends for their father’s implicit role in the extermination of these men’s families; neither marriage ended well. A niece, Christiane, married Stanley Kubrick, who as a Jew was both shocked and fascinated by her relationship to Veit Harlan; he at one point planned to make a film on the Nazi director. Christiane’s brother ended up producing some of Kubrick’s films.

One thing that struck me was the generational difference in the attitudes toward Jud Süss itself. The first generation of sons, daughters, nieces, and nephews find it powerful, reprehensible, and disturbing. One of the granddaughters, however, considers it “so cheesy, and really banal, too,” wondering how anyone in the 1940s could have taken it seriously. This seems to reflect an attitude that many young people have toward old films;  she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

The filmmakers had extensive access to good prints of several of Harlan’s major films. One, Der Herrscher (“The Master,” 1937), deals with a factory whose owner is a strong leader type. The frame at left shows off Harlan’s feel for crowds that made him the equivalent for fiction film to Leni Riefenstahl as a documentarist. (Indeed, one might suspect a bit of influence here.) There are also home movies, some taken behind the scenes during the filming of Harlan’s Nazi-era films. Munich archivist Stefan Drössler adds some historical perspective. The exhibition shown in the film provides glimpses of key documents.

Harlan could be quite useful in the classroom. Obviously courses on German history would benefit from it. Film history classes could show it in a unit on Nazi cinema, either in combination with or as a replacement for Jud Süss or one of the other major Nazi film. But it also gives an interesting perspective on the post-war decades and the ways in which guilt and expiation could linger across generations.

Thanks to my friend Marianne Eaton-Krauss for recommending this film to me!

[Added October 31: Critic Kent Jones has kindly written to point out that Felix Moeller is Margarethe Von Trotta’s son. Kent has written a piece on Veit and Thomas Harlan in the May/June 2010 issue of Film Comment.]

The launch of a Russian DVD series

The Russian Cinema Council (RUSICICO) has recently released the first five DVDs in its new “Academia” series. The first group comes from the Soviet silent and early sound era: Strike, October, Happiness, The Great Consoler, and Engineer Prite’s Project. They can easily be ordered on the company’s website. Googling will find a few smaller online companies in Europe that sell them, but they are not available (yet, at least) from the larger sites like Amazon.

[January 31, 2012: Hyperkino has announced that its DVDs can now be purchased at a British site, MovieMail. For more on Hyperkino, see here.]

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

The prints of Strike and October are both the familiar step-printed versions. The visual quality is reasonably good.

(We did not purchase the Happiness disc, since the film had already been available in DVD and we’re not Medvedkin specialists.)

The most important contribution of the series so far has been to make two rare Kuleshov titles available to the general public for the first time. Engineer Prite’s Project was his first film. Previously it was available in archives in a print lacking intertitles. The story was so difficult to follow that the film seemed to be incomplete. Now, with the intertitles reconstructed and inserted into the film, it makes sense. It’s a short feature about industrial intrigue, notable in its mixture of traditional European tableau staging style and some sophisticated American-style editing that was a complete innovation for Russian cinema. The release of Engineer Prite’s Project on DVD fills a large gap in the history of the Soviet silent cinema, since it was the first film by one of the group that would form the Montage movement. Indeed, the fast cutting in a brief fight scene looks forward to that movement:

The DVD also includes a documentary, The Kuleshov Effect, made in 1969. It’s a helpful overview, with clips from the major films up to The Great Consoler, along with interviews with Kuleshov, scenarist and Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovski, and others. It’s just under an hour and would be a great teaching tool for a history or theory class.

If Engineer Prite’s Project is of interest mainly for its historical significance, The Great Consoler is perhaps Kuleshov’s masterpiece. The complex, multi-leveled narratives so popular in contemporary cinema have nothing on this film’s storytelling. It shifts among three levels with thematic parallels. In one, an abused, miserable shop girl (played by Alexandra Khokhlova, Kuleshov’s wife and leading proponent of the “biomechanical” school of acting) reads O. Henry short stories as escapism. In another, O. Henry himself is seen in prison (as he was in real life). In a third, we see a dramatization of his tale of convict Jimmy Valentine (“A Retrieved Reformation”). Each level is filmed in a slightly different style, and the moralistic lesson–those who suffer from exploitation under capitalism find only hollow consolation in popular culture–is somewhat undercut by the zestful stylization with which Kuleshov presents the sentimental tale of Valentine.

Chaplin (Slowly) Becomes The Little Tramp

On October 26, Flicker Alley is coming out with another of its big boxes of restored films. (Amazon has it available for pre-order.) This time it’s four discs containing a group of 34 of Charlie Chaplin’s Keystone-era films (of the 35 he made there). The press release describes the lengthy process of finding and restoring prints, which involved several archives:

With the support of Association Chaplin (Paris), 35mm full aperture, early-generation materials were gathered over an eight year search on almost all the films from archives and collectors  around the world, and were painstakingly piece together and restored by the British Film Institute National Archive, the Cineteca di Bologna and its laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy, and Lobsters Films in Paris. Most are now clear, sharp and rock-steady, although some reveal that their source prints are well-used and a handful survive only in 16mm.

around the world, and were painstakingly piece together and restored by the British Film Institute National Archive, the Cineteca di Bologna and its laboratory L’Immagine Ritrovata in Italy, and Lobsters Films in Paris. Most are now clear, sharp and rock-steady, although some reveal that their source prints are well-used and a handful survive only in 16mm.

The earlier films in the set remind us that Chaplin began as a player in films where Mabel Normand was the star attraction (and she directed them herself). He didn’t always wear his “Little Tramp” outfit, either. Such films as The Property Man, The Rounders (co-starring Fatty Arbuckle), and Tillie’s Punctured Romance (restored by the UCLA archive) are included. A trim little booklet by Jeffrey Vance includes historical background and program notes. Original musical accompaniment is provided by Neil Brand, Robert Israel, and others. On-disc bonus materials include a documentary, “Inside the Keystone Project” and a couple of Chaplin-related silent films from the era, including a cartoon featuring him as a character.

Chaplin devised his “Little Tramp” outfit during this early era, though he didn’t use it in every Keystone film. He wasn’t yet the poignant figure of the later 1910s and 1920s. In Mabel at the Wheel, for example, he’s a pugnacious, bomb-wielding villain, with Mabel Normand, who directed the film, in the lead. (At left above, he belatedly  discovers that Mabel is no longer seated behind him on the motorcycle.) Chaplin buffs will have a field day with this set. The clarity makes it easier to spot the many comics who play bit roles here. Mack Swain wanders through, Mack Sennett has a small role as a yokel, and one can see a very young Edgar Kennedy seated behind Chaplin in the bleachers (right).

discovers that Mabel is no longer seated behind him on the motorcycle.) Chaplin buffs will have a field day with this set. The clarity makes it easier to spot the many comics who play bit roles here. Mack Swain wanders through, Mack Sennett has a small role as a yokel, and one can see a very young Edgar Kennedy seated behind Chaplin in the bleachers (right).

Each film is preceded by a title card that specifies the source material for the restoration, as well as the archives and other institutions involved. Mabel at the Wheel, for example, was assembled from four nitrate prints held by various collections. As the frames here indicate, it’s generally very clear and undamaged, though occasionally a shot from a more worn print appears.

We often complain about seeing films for the first time on DVD when they were meant to be seen on celluloid projected on the big screen. But for rare silent films like these Chaplin shorts, DVD replaces the old 8mm and 16mm prints that I remember from my graduate-school days in the 1970s. Our friend and colleague Frank Scheide, who was writing his dissertation on Chaplin’s music-hall background, would present programs of such prints in his home, but there were items that remained elusive. (Frank has co-edited two anthologies on Chaplin’s later films; see here and here.) Now we’re lucky enough to have archives restoring films in part to make available in the new format. Most of these images are far better quality than 8mm or even 16mm could render.

As with the giant Georges Méliès boxed set released in 2008, the new Chaplin discs make it easy to go through his career in strict chronological order, either as the films were made or as they were released (often not the same thing in those early days). The set is a vital item for collections of silent films and will no doubt feature among the nominees in the DVD awardsfor next year’s Bologna festival, Il Cinema Ritrovato. Three Hyperkino titles were among last year’s winners.

Mark your calendars!

On November 7, Turner Classic Movies will be showing the new restoration of Metropolis (8 pm Eastern time), followed by a one-hour documentary Metropolis Refound (11 pm Eastern time), on the discovery of a nearly complete print in An Argentinean archive. On November 4, the restored Pandora and the Flying Dutchman (1951; starts at 10 pm Eastern time) will be shown. It’s by the little-known auteur Albert Lewin; if you love Powell and Pressburger movies, you’ll probably love this film. Every Monday from November 1 to December 13, TCM will air its original series, Moguls & Movie Stars (8 pm Eastern time). Each episode will be followed by several films of the era discussed. One highlight not to be missed is Lois Weber’s wonderful 1921 feature, The Blot. It’s probably the only film ever made about the low pay of university professors, but its real strength is in the character study of haves and have-nots living next door to each other. Back when I taught a history of silent cinema class at the University of Iowa in 1980/81, this was one of the films I showed to demonstrate that silent films weren’t as simple and naive as young people today might assume. (The other was King Vidor’s 1924 Wine of Youth.) Set your recorders, since The Blot airs at 4:45 am EST on November 8. For more highlights, keep checking the TCM website, which hasn’t yet posted its November schedule.

Harlan: Im Shatten von Jud Süss

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.

DVDs for these long winter evenings

Kristin here:

Coming back from a trip has pleasant and unpleasant consequences. Bills piled up, but so did stacks of packages, books and DVDs we forgot we had ordered or ones sent to us out of the blue.

The intrepid companies that rescue and issue silent films on DVD have been busy. All are past winners of awards in the Cinema Ritrovato festival’s annual ceremony, and obviously they are working hard to keep their standards up. (For a pdf listing all the winners since the awards began in 2004, click here.) Two of my favorite directors are represented.

Much More Méliès!

In 2008, Flicker Alley won “Best Box-Set” for its monumental collection “Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema” (five DVDs with 173 films). Amazingly, 26 more films (or fragments, in one case very short) have been discovered since its issue. These will be released in the U.S. on February 16 on a single disc titled “Georges Méliès Encore.”

One of these, Le Manoir du Diables/The Haunted Castle, from 1896, contains something like 26 cuts, all stop-motion effects. I wouldn’t have thought such an elaborate production would have been possible so early in the history of cinema, but here it is. It’s also interesting for having been shot outdoors, with what looks like a flat gravel “floor.” The lighting changes dramatically at one point, with the sun in a different position after an obvious pause in filming, and for a time the shadow of a tree is visible in the right foreground. The set is also quite elaborate for such an early production. Watch for a moment when the actors bump into the set and cause it to wobble alarmingly.

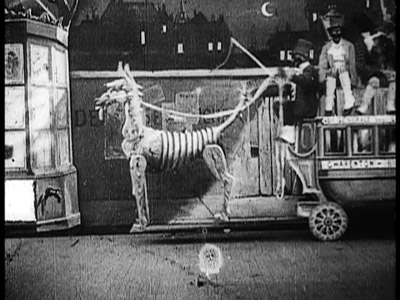

I had long been intrigued by production photos and sketches from a lost Méliès film, L’omnibus des toqués ou Blances et Noirs/Off to Bloomingdale Asylum. (I have no idea why this English title was chosen, since it has nothing to do with the action. “Toqués” would translate roughly as “crazies.”) The thing that intrigued me was a strange, mechanical-looking horse that draws the omnibus of the title. Finally I got to see it, and it was worth the wait. The horse is good, to be sure. It pulls a small coach with five black-face minstrels sitting atop it.

It’s not terribly apparent from the film, but a surviving Méliès sketch makes it obvious that the horse farts, driving the minstrels to jump off. The horse and coach depart, and the four minstrels begin an elaborate game of slapping and kicking each other in rhythm, each blow turning one into a white-clad pierrot figure and then back into a minstrel. It’s another of Méliès’ rapid-fire set of stop-motion substitutions, with the positions of the figures matched with astonishing precision. A tiny masterpiece in one minute and four seconds, counting the title card.

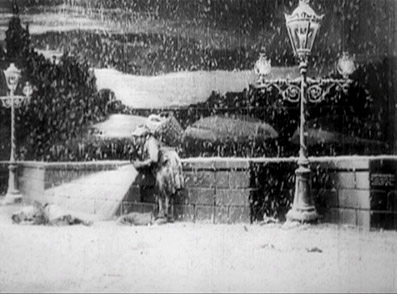

There’s a wide range of genres represented on the disc, including staging of news events, as in Éruption volcanique à la Martinique/ Eruption of Mount Pele (1902); chase films, like Le mariage de Victoire/ How Bridget’s Lover Escaped (1907); and even tear-jerking melodrama, like Détresse et charité/ The Christmas Angel (1904). The latter has an interesting stop-motion effect to add a white-painted stream of light as a rag-picker turns on his lantern to see the little beggar-girl asleep in the snow.

An otherwise surprisingly pedestrian 1905 film, L’ile de Calypso/ The Mysterious Island has one impressive moment, when a giant hand (Polyphemus having been transferred to Calypso’s island) emerges from the dark of a cave to threaten Ulysses (who is a bit hard to see, standing against the rocks at the right of the cave).

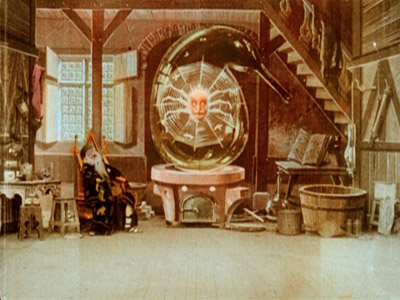

Was Méliès the first filmmaker to realize that leaving a large dark patch in part of set allowed things to be superimposed in that area without looking translucent? The best-known film to use the device is L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc/ The Man with the Rubber Head (1902), but many other films use it, including some on this disc. A few of the films have hand-coloring, including the early L’hallucination de l’alchimiste/An Hallucinated Alchemist, where the alchemist of the title dreams of a giant spider.

The state of preservation naturally varies enormously. One nearly pristine print is the amusing Satan en prison/Satan in Prison (1907). The title is vital, since the bulk of the action consists of a well-dressed man magically producing a series of items to furnish a bare room, culminating in his summoning up a charming lady to share his meal. Hearing the guards approaching, the man reverses the process, ending with a bare room when the two men enter. Finally he is revealed as one of Méliès’ favorite characters, Satan! (See frame surmounting this entry.)

I suppose we shall never have all of Méliès’ films, but there are now more than twice as many known to survive as when I was in graduate school. I look forward to a second encore.

Lubitsch, Lubitsch, Lubitsch

Another pleasant surprise among the heap of packages was Eureka!’s new boxed set of Ernst Lubitsch films from the years 1918-1921. If that sounds a bit familiar, that’s because this is the third such set to appear in just over three years. I’m not going to make a point-by-point comparison, but I’ll sketch some basic differences.

The German set, confusingly titled in English the “Ernst Lubitsch Collection,” came out in November, 2006 and is PAL, region-2 encoded. It contains five Lubitsch silents: Ich mochte kein Mann sein (1918), Die Austernprinzessin (1919), Sumurun (1920), Anna Boleyn (1921), and Die Bergkatze (1921). Its main bonus is a feature-length documentary, Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin—Von der Schönhauser Allee nach Hollywood. None is subtitled. The set won the Cinema Ritrovato’s prize as Best DVD of 2008.

The set was issued by the Munich company Transit Film, a government-owned 35mm distributor with a library of about 600 titles, drawn from across the history of German cinema. We’ve brought some of their prints to Madison for Cinematheque screenings. The sources of the films are primarily the Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau-Foundation and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv. It also produces documentaries like the one on Lubitsch. (The website offers German, English, and French language options.) It has also put out several DVDs under the name “Transit Classics.”

In the U.S., from late 2006 into 2007, Kino Video brought these five titles out as four individual DVDs (pairing Die Austernprinzessin and Ich mochte kein Mann sein on one disc). Apparently, although Transit’s set didn’t include the 1919 comedy Die Puppe, it made it available, and in December 2007, Kino brought it out on a disc with the Ernst Lubitsch in Berlin documentary—and at the same time issued a boxed set of all six features plus the documentary on five DVDs, called “Lubitsch in Berlin.” (All Kino discs are NTSC region 1; given that they were transferred from PAL versions, they probably run about 4% faster than the Transit versions.)

Eureka!’s set is also entitled “Lubitsch in Berlin.” It contains the same set of films, including the documentary, all also licensed from Transit. These are here arranged over six DVDs. Its unique material is relatively slight, consisting mainly of short original sets of liner notes and an original score for Die Puppe. One advantage is that Eureka!, as usual, has retained the German intertitles and added subtitles to them. (The Kino versions, in contrast, replace the original intertitles with English ones, which has been their practice on some, if not all, of their other DVDs.) Some or all of these intertitles may have been replaced, perhaps reconstructed on the basis of censorship records, as is often the case with restorations. Still, many viewers would want access to the German text as well as the English versions. The Eureka! set is PAL, and it doesn’t seem to have region coding.

For those unfamiliar with Lubitsch’s German films, these are a good introduction. The four comedies all hold up well today. The first three are built around Ossi Oswalda, a boisterous blonde comic who seems to have inspired Lubitsch to move away from broad slapstick to a more stylized, eccentric approach. Pola Negri, after acting such roles as Carmen and Madame Dubarry in the director’s costume pictures, revealed her comic talents in Die Bergkatze, his last German comedy.

Overall my favorite of the group is Die Puppe, so I’m very glad it’s been added. Some might prefer Die Austernprinzessin, which is indeed hilarious. But it mainly has the wealthy heroine’s home as its comic milieu. Die Puppe seems denser, with more characters and three comedy-generating settings: the rich uncle’s home, the art-nouveau cartoon doll shop, and the monastery where the hero takes refuge. Plus there’s the famous prologue, where Lubitsch himself sets up the premise that the characters themselves are simply dolls brought to life. (See below.)

I chose Ich möchte kein Mann sein as one of the best films of 1918. See here for a brief description and a frame at the bottom of the entry.

The conspicuous absence from this set is Madame Dubarry, the 1919 historical epic that made Lubitsch famous worldwide. Perhaps it’s not an ingratiating film at first viewing, but I found that it grew on me in repeated screenings. (I talk about some of its best scenes including one impressive long-take scene, in my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood.) Anna Boleyn took on British history in an attempt to replicate the success of Madame Dubarry, but I have never been able to warm up to it. That’s probably partly because Henny Porten simply did not bring the vibrancy to the title role that Negri had in Madame Dubarry and perhaps partly because the increased budget let to an overemphasis on huge sets and crowds of extras (above). The characters in Madame Dubarry seem comfortable in their period costumes; the ones in Anna Boleyn don’t.

I chose Die Puppe as one of the best films of 1919. See here for a frame from it, and one that demonstrates why I admire Madame Dubarry. Perhaps restoration work on the latter is going on at this moment, so that another DVD will someday join these on the shelf.

The other film in the collection, Sumurun, is a quasi-Arabian-Nights tale, starring Pola Negri as a seductive member of a traveling troupe of entertainers. Lubitsch plays his last film role as the hunchback clown who dotes hopelessly on her. The performance isn’t all that different from some of his earlier ones, but perhaps seeing his rather exaggerated acting style in the context of a non-comic film led Lubitsch to doubt his own abilities. Given that he was far better as a director than as an actor, his decision to stay behind the camera was a boon to future generations. To me, Sumurun is fascinating because it shows the first real signs of Lubitsch’s awareness of Hollywood continuity editing, a set of techniques he would thoroughly master over the course of his next half-dozen films.

It can’t have been easy to put together a 109-minute documentary on Lubitsch’s life before his move to Hollywood. In working on my book, I discovered how surprisingly few photographs of him at work onset survive. The studios where he worked don’t survive, though there are shots of the giant Ufa Tempelhof sound stages that now stand where those studios were.

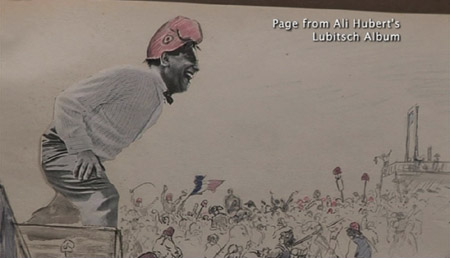

Several prominent historians are interviewed, including archivist Enno Patalas and historian Hans Helmut Prinzler, co-editors of Lubitsch (an extremely useful book, published by the Verlag C. J. Bucher i 1984) and archivist Jan-Christopher Horak (whose master’s thesis was on Lubitsch’s relation to Ufa). Lubitsch’s surviving family members, seen above at the unveiling of a “Lubitsch lived here” plaque, were interviewed: his niece Evy Bettelheim-Bentley (left), granddaughter Amanda Goodpaster (center), and daughter Nicola (right). Lubitsch’s theatrical career is well covered, and generous clips from the pre-1918 era demonstrate his move into comic acting for films. Audio interviews with Henny Porten and Emil Jannings include a charming anecdote she tells about how apologetic Jannings was after the scene in Kohlhiesels Töchter in which his character jerks a bench out from under her–an incident that left her with a bruised rump. In between scenes, directors who have been awarded the Ernst Lubitsch prize, such as Tom Tykwer, discuss the master. Perhaps the most interesting artifact shown is an album Lubitsch’s regular costume designer and friend Ali Hubert made for him, combining drawings with photos of Lubitsch and little poems; below he depicts Lubitsch directing Madame Dubarry. Ultimately Hubert gave it to the director as a gift.

The documentary feels a trifle thin at times, and it makes no real attempt to cover Lubitsch’s Hollywood career, presumably because of the difficulty of getting permission to use clips. But it certainly would be a useful teaching tool for introducing students to Lubitsch’s life before Hollywood.

(Thanks to Ben Brewster for helping determine some of the differences among these three Lubitsch boxes.)

The Man with a Movie Camera before The Man with a Movie Camera

In 2007, the Cinema Ritrovato awarded the “Edition Filmmuseum” series from the Filmmuseum Munchen its DVD award for “Best Series.” We’ve mentioned this series before, in relation to its Walter Ruttmann disc and its DVD of Robert Reinhert’s Nerven.

Now the Filmmuseum has issued a two-disc set offering two of Dziga Vertov’s silent feature documentaries, A Sixth Part of the World (1926) and The Eleventh Year (1928). The former is a poetic look at the various and farflung ethnic groups within the U.S.S.R., the population of which made up one sixth of the world. It was the first of Vertov’s films to be strongly praised, seeming to justify his theory of the Kino-Eye.

Those expecting anything as experimental as Man with a Movie Camera might be disappointed. There are some of the familiar camera tricks, such as split-screen effects:

The typography of the intertitles reflects the constructivist style of the 1920s:

The discs have optional English subtitles.

Having seen these films during my research, I haven’t watched the discs in their entirety. The quality looks as good as can be expected. Michael Nyman’s music is certainly not authentic to the period, but what I heard of it sounded strangely appropriate to the images and effective as accompaniment.

The discs also include an interesting bonus, a German propaganda short, Im Schatten der Maschine, by Albrecht Viktor Blum, which used footage from The Eleventh Year to make a film critical of the technical progress which Vertov was praising in his own movie. (Since The Eleventh Year had not yet appeared in Germany, Vertov was actually accused of plagiarizing from Blum rather than the other way round.)

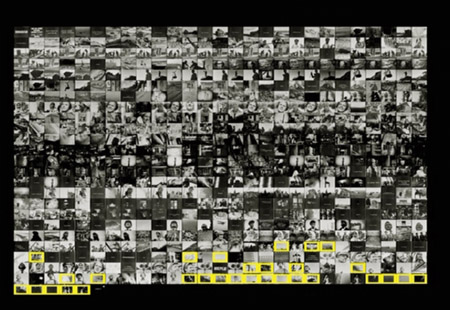

Another bonus is a 14-minute documentary, Vertov in Blum: An Investigation (optional German or English narration). This fascinating short begins by demonstrating that Vertov himself and possibly others almost certainly cannibalized footage from The Eleventh Year for Man with a Movie Camera and other films. It goes on to hypothesize that the final montage in Im Schatten der Maschine may consist of footage that Vertov later removed from The Eleventh Year‘s negative. Side by side comparison of prints using Final Cut Pro revealed matching shots between the two films, highlighted in yellow here:

Blum’s film culls shots and even edited passages primarily from late in Vertov’s film, but it continues beyond the end of the surviving version of The Eleventh Year. Some of those shots have been traced to other, later Vertov films, and the archival sleuths are still comparing prints and looking for the rest. They may have found the missing ending from The Eleventh Year; at least, the evidence makes that idea very plausible. Whether they are right or not, though, the short demonstrates the painstaking work often necessary in the restoration of films.

These companies and archives have certainly not been resting on their laurels. It will be exciting to see what the upcoming Cinema Ritrovato’s awards will highlight.

2-4-6-8, whose lipdub do we appreciate?

DB here:

“There is really no such thing as Art. There are only artists.” I tend to interpret the disarming opening of Ernst Gombrich’s Story of Art as a protest against the idea that art has an essence that unfolds through history. Those of us in film studies can spot the heritage of this Hegelian idea in one standard story that is told about how editing came to be a dominant technique. According to the formula, editing is “essentially cinematic,” but this essence didn’t reveal itself immediately. It emerged in phases, thanks to the insights of brilliant creators (Méliès, Porter, Griffith, the Russians). Understanding cinema’s history, according to this view, means tracking how film revealed its inherent nature.

In saying that Art doesn’t exist, Gombrich isn’t trying for an elaborate philosophical argument. He’s suggesting a way of understanding art history. His abrupt two sentences suggest that the historian shouldn’t presume that any art has an essence, a secret core that dictates how its history unfolds. He proposes seeing continuity and change in what we call the arts as springing from concrete activities of individuals and groups. Cinema’s history then becomes an account of the creative decisions of filmmakers faced with particular demands and problems. Some of those decisions can converge across the community. The results are trends, such as the increased use of editing, which have real consequences but which are aren’t the result of some secret, essential process.

Once we try to analyze art in terms of what creative communities have sought and achieved, we can ask how artists tend to behave. Across his career, Gombrich stressed that artists are sensitive to their circumstances. What tasks are assigned to the artists? What are the traditions and current fashions? What are the tastes of patrons? What constraints are put on the art-maker? How is art taught? How can the ambitious artist achieve distinction? (“What is there for me to do?”) What are the tricks of the trade at any moment? How do artists borrow from one another? And how might they compete with one another?

We often underrate competition as a stimulus to creativity. Gombrich notes that “the Dutch masters vied with each other, trying to outdo their rivals in certain accomplishments.”

Stressing the relevance of traditions not only implies an attention to the way art feeds on art; it should also make us aware of the cumulative nature of any such skill. What happens in such a hothouse atmosphere is that ambition leads to competition and frequently also to specialization, as it notoriously did in Holland.

In cinema, we might profitably consider competition as one source of the diversity within a tradition. I suspect that the great Soviet directors of the 1920s not only shared ideas but also competed by testing ever farther-out ideas about cutting. They also specialized in the manner Gombrich suggests by cultivating particular effects or genres: Pudovkin’s character-driven pathos, Eisenstein’s dynamic crowd effects, Kuleshov’s exploration of popular genres, Dovzhenko’s boldly elliptical storytelling. I’ve often thought that the Warner Bros. cartoonists probably walked out of the first screenings of Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) with heavy hearts. How could they match that? They didn’t try. Instead, they cultivated something quite different: raucous, cynical, high-speed farce. And today, doesn’t it seem likely that Avatar took its final form as an effort to go beyond the CGI efforts of earlier directors—to prove that the director of Terminator II and The Abyss was still the King of the World of SPFX?

Boys and their long-take toys

One of the most visible arenas of cinematic competition is the sustained tracking shot following several characters. It requires a sort of virtuosity, or at least logistical skill, in coordinating everything—the speed and consistency of the movement, the passage of people in and out of the shot, the consistency of framing and focus, the timing of new information. Once somebody has executed such a shot, the challenge is thrown down to others. Can you make yours longer or fancier?

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I noted that Brian De Palma saw just such a challenge in Raging Bull’s famous tracking shot from the dressing room to the prizefight ring. “I thought I was pretty good at doing those kind of shots, but when I saw that I said, ‘Whoa!’ And that’s when I started using those very complicated shots with the Steadicam.” This sort of schoolyard one-upsmanship is probably what Christine Vachon had in mind when she called the single-take scene a “macho” choice.

There are some longer-term trends as well. Elaborate takes used at the start of a film can be found in the 1930s and 1940s (e.g., Ride the Pink Horse, 1947), but Welles laid down a clear marker in the opening of Touch of Evil (1957). Thereafter, starting a movie with an intricate, sustained camera movement became something of an emblem of directorial ambition.

Already, however, Dreyer, Ophuls, and Mizoguchi had used long takes, usually with camera movement, as building blocks of a film’s overall design. With Rope (1948) Hitchcock raised the possibility of making an entire film out of even fewer such shots, an initiative continued by the Hungarian Miklós Jancsó, who developed the choreography of such shots to a new level by incorporating crowds, zooms, and rack-focus passages. Béla Tarr and Gus van Sant have been modern exponents of the technique.

It was probably inevitable that somebody would try to make a feature-length film consisting of a single moving shot. Josh Becker’s Running Time (1997) renders a heist in what purports to be one take; there are cuts, but they’re pretty well disguised. Sokurov’s Russian Ark (2002; above) uses video technology to create a feature out of one genuine take, “a single breath” as he called it. At the same time, Sokurov added the condition that the shot would be an exploration of a labyrinthine space, in this case the Hermitage, and a trip through different eras of Russian history.

My lipdub can lick your lipdub

Perhaps it was Russian Ark, or maybe just TV walk-and-talks, that inspired the recent cycle of single-take video lipdubs. In these the camera moves through a locale and picks up one person after another, all lip-synching the soundtrack. September’s massively popular lipdub from l’Université de Quebec à Montréal may have furnished the prototype. In the US, a pair of current examples neatly illustrates how borrowing and competition among moviemakers can yield intriguing results.

As you probably know, Shorecrest High School in Shoreline, Washington, mounted a very complicated lipdub—one take coasting through the school, picking up dozens of teens lipsynching to Outkast’s “Hey Ya!” before they all assemble in a theatre for a final shout-out. There are some somersaults too, which make any movie better. It is here.

But high school rivalries resurfaced. Shorewood High School, traditionally at odds with Shorecrest in sports and band, struck back with a lipdub of Hall and Oates’ “You Make My Dreams Come True.” The new entry raised the stakes by shooting the action backward, somersaults included. Here it is.

There’s no shortage of backwards videos, but the Shorewood clip plays in clever ways with our biases in perceiving movement. Because we’re wired to grasp motion as advancing in time, we can’t easily reconstruct the actual movement that the figures executed. After seeing the film many times, I still found it hard to visualize the actual progression of the shoot, starting from the assembled crowd and ending on the young woman running backward to the vehicle that pulls away. (A forward version is here.) Moreover, both forward and backward motion have an uncanny symmetry, so that it’s hard to detect the latter except through subtle cues like the way garments fall or a gait with a special snap. Even the moments that flaunt the reverse-motion device, such as things originally tossed down into the frame, seem instead to fly up and into the hands of bystanders.

The stakes have been raised. What will Shorecrest come up with? A radical change of angle? (An entire lipdub done from a very high or low vantage point?) Or maybe a more demanding location? (With spring coming, I’d vote for a miniature-golf course.) Anyhow, my imagination is more limited than the filmmakers’. All that matters for my purposes is that the very fact of competition gave birth to a pair of ingenious and sprightly movies.

If you’re thinking that I wrote this simply to give everyone who Googles “Gombrich lipdup” at least one result, you miss my point. Just as Gombrich was never shy about using advertising imagery and children’s drawings to illustrate some basic principles of visual psychology, so we ought to notice any examples that vividly show how artists strategize in order to create something new within a tradition. Which is to say: Yes, I consider the young filmmakers of Shorecrest and Shorewood artists. Why not?

Gombrich’s essay on Dutch painting first appeared as “Mysteries of Dutch Painting,” New York Review of Books 30, 17 (10 November 1983), 13-17. It is reprinted in his Reflections on the History of Art (London: Phaidon, 1987). Shorewood has supplied a sort of making-of bonus here, with some more challenges to Shorecrest thrown in. To see the genre coopted by politicians (who apparently can’t get all their cohorts together in the same space), go here (thanks to Camilla Lugan). Maybe US politicos could get some more support if they tried bopping like this? They could hardly look sillier than they do already.

PS 31 January: Jason Mittell of Middlebury College has alerted me to his students’ lively long-take lipdub on the virtues of recycling.

PPS 1 February: Yogesh Raut writes that another historical precedent for the dueling lipdubs would be one older than the Quebec one I cited.

In your recent entry on lipdub videos you cite a video made in 2009 by students in Quebec as “the prototype.” I think a more likely candidate is this video made by a company called Connected Ventures and first uploaded in April 2007:

While there have obviously been a ton of similar videos made since then, I think the folks at CV (who I have no connection with) probably deserve a little hat tip as innovators. Of course, it’s possible that they were copying someone else, but in general they seem to be recognized as the starters of the craze (see here, for example).

It’s good to learn this. There are probably other precedents as well. I’d just say that a prototype need not be the first work in a genre tradition; rather, it’s a fully developed, typical instance. We take Little Caesar as a prototypical gangster film, but it’s not the first. The Connected Ventures project is indeed a single take, and it follows various people lip-synching. But it doesn’t explore a building in a targeted way, making the revelation of new space add visual variety, and the walking characters seldom pass us from group to group in tight choreography (it relies more on loose pans). Like other early efforts in a genre, it seems simpler and rougher than later entries. I suppose that supports my point that competition can spur filmmakers to surpass their peers; it seems that later lipdub adepts took up the challenge to make the single take more intricate. Still, I should probably have called the Canadian video “a prototype” rather than “the prototype.” Many thanks to Yogesh for calling my attention to a particularly early work in the genre.

2 May 2010: Tonight’s Simpsons episode, “To Surveille, with Love,” opens with a single-take lipdub pastiche/ parody showing Springfield’s citizens moving to Ke$ha’s Tik Tok video. Next morning: It’s here.