Archive for the 'National cinemas: Russia and USSR' Category

Some cuts I have known and loved

DB here, belatedly:

We’ve been so busy revising our textbook, Film History: An Introduction, for its third edition that we’ve had no time to see new movies, let alone blog on our regular schedule. To those loyal readers who have been checking back occasionally, we say: Thanks for your patience. An entry that should intrigue you is in the works, possibly to be posted very soon.

In the meantime, here’s an item on a subject I’ve been meaning to slip in at some point. It’s a tribute to cuts I admire.

Warning: Superb as Eisenstein’s, Ozu’s, and Hitchcock’s cuts are, I’m deliberately leaving them out. Too obvious!

Kata and cutting

Okay, Kurosawa is an obvious choice too, but I can’t pass up some of the first outstanding cuts I noticed in his work, back when I was projecting movies for my college film society. The cuts occur during the climactic battle of Seven Samurai (1954).

As is well-known, Kurosawa shot the sequence with several cameras using different focal-length lenses. What is less often acknowledged, I think, is the power of certain cuts as they combine with fixed camera positions. In his last films, Kurosawa would rely strongly on long-lens shots that pan over the pageantry of his crowd scenes, but here he exploits static frames.

In the eye of the battle, Kambei fires his arrow in one shot, and a horseman falls victim to his marksmanship in the next. So far, so conventional. But what’s unusual is that we don’t actually see the arrow hit its target. Kambei fires, and Kurosawa cuts to an empty bit of the town square, churned with mud and dimly visible through horses’ legs. Only after an instant does a fallen bandit skid into the telephoto frame.

The same thing happens when Kambei shoots his second arrow: we must wait for the victim to plunge into the frame.

The result, I think, is a sense of exhilarating inevitability. The camera knows that the horseman will fall, and it knows exactly where. That’s a way of saying that Kurosawa’s visual narration fulfills our expectation, but with a slight delay. The empty frame prompts us to anticipate that the man will be hit—why else show it?—and we have a moment of suspense in waiting to confirm what we expect. Moreover, the force of Kambei’s arm is given us through a principle of Movie Physics: motion communicated to another body is magnified, not diminished, and the fixed frame allows us to see just how far the bodies are propelled. The arrow must have been Homerically powerful if it sends these men to earth with such impact.

Most directors would have panned to follow the victim as, wearing the arrow, he tumbled off his horse and hit the ground. This choice would have been natural given the multiple-camera situation. Instead Kurosawa had his camera operators frame the exact spot the stuntman would hit and wait for the action to hurtle into the shot. The patient expertise of Kambei’s marksmanship has its counterpart in the confidence of Kurosawa’s style. (1)

The moving image, Mr. Griffith, and us

Then there’s Intolerance (1916).

The Musketeer of the Slums is trying to seduce the young man’s wife, the Dear One. He pretends he can retrieve her baby. But his earlier conquest, the Friendless One, has followed him to the tenement, and at the same time the Boy has learned about the Musketeer’s visit. As the Musketeer attacks the Dear One, the Boy bursts in. The two men struggle and the Boy is momentarily knocked out; the Dear One has swooned. So no one sees what really happens next: From the window ledge the Friendless One fires her pistol and downs the gangster. She flees, and the boy believes that he is the killer. He will be charged with the murder.

Here’s what I admire. Griffith sets the situation up with his usual rapid crosscutting—the Musketeer and the Dear One struggling, the Boy returning, and the Friendless One crawling out on the ledge. When the fight starts, Griffith shows the Friendless One growing wild-eyed at the window. She fires once, and Griffith gives the action to us in three shots: a medium shot of her in profile, a medium-long shot of the pistol at the window (irised so we notice it), and a long-shot of the room, as the Musketeer is hit.

Griffith repeats the series of shots when the Friendless One fires again.

This time the Musketeer staggers out to the hall and dies. Neatly, Griffith gives us three more shots, but omits the setup showing the Friendless One. Cut to the curtains again, with her hand waving the pistol, then to another long shot of the room as the gun is tossed in, and finally to a close-up of the pistol landing on the floor.

If you’re looking for a pattern, the pistol in close-up is in effect substituted for the shot of the Friendless One at the start of each cycle. But I’m most interested in the shots of the pistol. The first one at the window goes by at blinding speed—ten frames in the two prints Kristin and I have examined. (2) That works out to a bit more than half a second, if you assume 16 frame per seconds as the projection rate, which was common at the time.

Okay, fussy, but I’ve already confessed that I turn into a frame-counter, when I get the chance. The second shot of the pistol poking out of the curtains, parallel to the first, is also ten frames long. Griffith seems to have been a frame-counter too.

What’s most remarkable is that the long-shot of the pistol being flung into the room is even briefer than these closer views—only seven frames long, or less than half a second at 16fps. As a nice touch, the close-up of the pistol landing in the corner is twice that (15 frames).

In the decades that followed, directors would believe that long shots shouldn’t be cut as fast as close-ups, so the Intolerance passage can strike us as a typical Griffith misjudgment. But I admire his willingness to cut long shots so fast. It certainly creates a percussive accent. In case we didn’t catch the story point, the close-up of the pistol hitting the floor clinches it.

This is the sort of sequence that the Soviet filmmakers probably learned from. They may even have gotten ideas from Griffith’s interspersed black frames (two by my count) before each of the shots of the pistol thrusting out of the curtain. (3)

Behind the desk

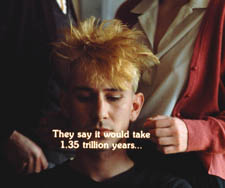

Speaking of the Russians, one of my favorite cuts in Pudovkin’s movies comes during a confrontation in The End of St. Petersburg (1927). The somewhat oafish young worker known only as the Lad, who has sold out his comrades, attacks the boss Lebedev in his office. He seizes the boss and shoves him down, jamming him between his desk and the window. We see the action from one angle and then what seems to be an opposing angle.

Actually, this is a big discontinuity. Using the desk, the telephone, and the window as reference points, we can see that in the first shot, the Lad moves in from the left side of the desk to push the boss down. In the second, he has come in from the right side and Lebedev’s head is pointing in the opposite direction. We can see the weirdness of this more clearly if we simply flip one of the frames: now it looks like a consistent change of angle.

Pudovkin has created an impossible event. But the cut gives the strong sense of graphic conflict that the Soviets (not just Eisenstein) sought, creating a kind of visual clatter to underscore the violence of the action. It’s possible that Pudovkin actually flipped a “correct” framing to create the disjunction, as some of his contemporaries did. (4)

Meg, all aflutter

Pudovkin’s cut reminds us that filmmakers can get away with a lot if they change the angle drastically. It’s harder to spot a cheated element or a mismatch if the new shot makes us reorient ourselves. Why does this happen? That’s a subject for research, as I’ll suggest at the end.

Here’s another tricky item. In Kate & Leopold (2001), Kate has brought her time-traveling guest to an audition for a butter commercial. In the studio, he’s behind her as she tries to convince her colleagues to watch him. As she talks, she first watches Leopold in the monitor above them, then swivels to talk to her boyfriend and other suits. The camera positions change 180 degrees.

This drastic shift works to prepare us for a remarkable cut a little later. Kate waves her hand, saying she only needs two minutes. She pivots her body, moving her hand downward.

Cut 180 degrees to a setup similar to the one we’ve seen earlier: She drops her hand to her side as she swings to us.

The gesture is smoothly matched. The only trouble is that it’s executed by the wrong hand. In the first shot Kate is wiggling her left hand, but in the second, it’s her right hand that continues the movement and drops to her hip.

I don’t think that many people would notice this. Indeed, when I first saw the film, I felt a bump hereabouts, but when I watched it over again on DVD, it looked fine to me. Then I watched it again and saw what was wrong. Even then, I thought I might be hallucinating. It’s one of the trickiest cheats I know of, and it’s beautifully done.

The real question is: Why don’t we notice it? We usually say, “Because we’re watching the story and ignore little irregularities.” But that’s not very satisfactory. Why isn’t the wave of Kate’s hand part of the story? We certainly notice it as expressing her attitude—hence as part of the story. And if you didn’t notice the disjunction in my End of St. Petersburg example, the same question arises: Isn’t the Lad’s attack on the boss the very story action we’re watching?

Consider the alternative. If director James Mangold had matched the left hand, it would have to cross the center of the frame as Kate pivots, shifting from screen left to screen right before landing at her hip. It would have been ostentatious and somewhat graceless, and perhaps that would have been distracting. So the mismatch is perhaps a line of least resistance, a compromise–as so many stylistic choices are.

In addition, Kristin suggests that our pickup is made easier by the placement and action of the hand. In both shots it’s quite central and moving in the same direction at the same rate, so that it’s easy to read as a graphically continuous element across the cut.

Perhaps too the fact that we’re switching our position 180 degrees leads us to expect, wrongly, the sort of reversal we get here—the way that we think our reflection in a mirror is the way we really look. And of course the earlier 180-degree switch, in which no mismatch occurs, probably serves to prime us for the shift in orientation this provides.

Mangold doesn’t mention the cut in his director’s commentary on the Kate & Leopold DVD, but when I asked him he said: “I think of shots as blocks, like legos or words. I don’t want them to resolve–come to an end. . . . Movement cuts work as long as the action is somewhat similar. The tough continuity cuts when you have a mismatch are the still ones.” Even if the mismatch here was accidental, it works very well. More generally, like other mismatches this one obliges us to think about what we see and what we don’t see when we watch a movie.

Hawks’ eyes

Among the many pleasures of Howard Hawks’ movies are their lovely matches on action. Of course his editors had a lot to do with this, but Hawks clearly had to provide the right footage so that it could be precisely matched. Bringing Up Baby (1938) yields a crisp cut as Susan, perched on the constable’s desk, strikes a match. (I show the cuts from a 16mm print; enough of this video stuff.)

Here Hawks seems to rely on what’s been called the two-frame rule: If you’re going to match on action, overlap the action by two frames to show a bit of the action again. This allows the audience time to absorb the fact of the cut and then to see the action as continuous. But Hawks could be quite cavalier about his matches as well. The golfing scene from Bringing Up Baby is full of wild cuts.

The caddies advance and recede, Susan and David are caught in different postures, and at some cuts they’re striding across different parts of the course. These cuts have a swagger about them, as if Hawks is daring us to spot his outrageous cheats. How many of us do?

All these trompe l’oeil effects can be studied psychologically, and prominent researchers who have tested such effects in the laboratory are attending our 11-14 June meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. Dan Levin studies discontinuities in film from the standpoint of “inattentional blindness”; here he’s interviewed by Errol Morris. Barry Hughes of Arizona State University at Tempe has probed the two-frame rule, and he’s talking in Madison as well. Go here for more information; I’ve plugged the event previously here.

Next time, we expect: Secrets of film restoration.

(1) Kurosawa has prepared us for this passage when Kikuchiyo’s sword attacks the bandits earlier in the sequence. There too a shot of his flailing stroke is followed, after a pause on a patch of mud, by a falling horseman. But the calm deliberateness of Kambei’s drawing of his bow enhances the sense of inevitability, I think. Kiku does his damage through furious energy, but Kambei hits his mark thanks to a mature warrior’s almost contemplative precision.

(2) Forget checking these frame counts on DVD. I get several different counts, depending on the player I use. For reasons discussed here, DVDs don’t preserve the original film frames, and in a fast-cut passage you can lose any sense of how many frames the shot lasted.

(3) By the way, Griffith died on 23 July 1948, my first birthday.

(4) For more on this extraordinary movie’s use of discontinuity editing, see Vance Kepley, Jr., The End of St. Petersburg (London: Tauris, 2003).

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

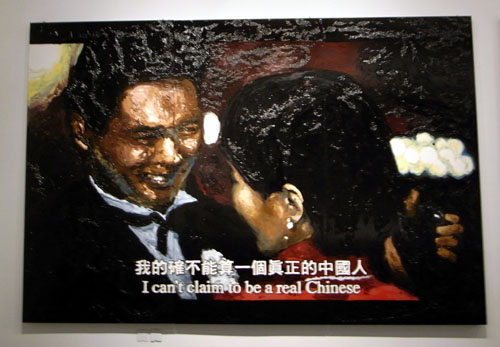

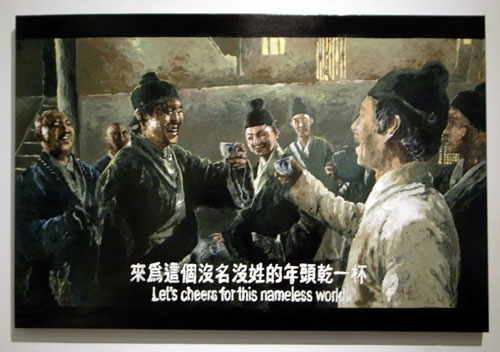

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

What happens between shots happens between your ears

DB here:

In Number, Please? (1920) Harold Lloyd plays a lovesick boy who’s been jilted by his girl. Moping at an amusement park, he sees her arrive with a new beau.

He shifts to another spot to watch them. When she notices him, she scorns him, and he reacts.

She and the escort stroll past, then she turns and cuddles up to him, making sure Harold notices.

Her flirting precipitates the rest of the action in this very funny short.

In this scene from Number, Please? Harold and the couple aren’t shown in the same frame. The action is built entirely out of singles of Harold and two-shots of the couple, with an especially emphasized close-up of the girl’s snooty reaction. The sequence is rapidly paced and carefully matched in angle; note the shift in eyelines as the girl and her beau walk a little way and then she looks back at Harold.

This approach to building a scene was consolidated in American studio cinema in the late 1910s, as we noted recently, and it soon spread around the world. One of the places it caught on most fervently was Soviet Russia.

Kuleshov glories in the gaps

The great director and theorist Lev Kuleshov always claimed that he and his associates learned the power of editing from American cinema. Russian films were slowly paced, consisting of long tableaus occasionally broken by an inserted closer view of an actor. (For examples, see my Bauer blog entry from the summer.) Kuleshov noted that the Hollywood films brought into Russia grabbed audiences’ interest more intently, and Kuleshov attributed this effect to the fact that the Americans exploited editing more fully, creating the scene out of many shots.

Kuleshov’s example was the formulaic scene of a man sitting at his desk and deciding to commit suicide. The Russians, Kuleshov claimed, would handle this all in one distant framing, with the result that the key actions were just part of the overall view. By contrast, Americans would shoot the scene in a series of close-ups: the man’s face, his hand taking a pistol out of a desk drawer, his finger tightening on the trigger, and so on. This gave the scene a powerful concreteness, and was cheaper to film besides (no need to have a full set).

But most American filmmakers didn’t create the scene wholly out of close-ups. Typically there would be an establishing shot before the action was broken down into detail shots. The process has come to be called analytical editing. (We discuss it in Chapter 6 of Film Art.) As the label implies, the cutting analyzes an orienting view into its important details.

Less commonly, as in our Number, Please? example, American directors could create a scene entirely out of separate areas of space, without ever showing a master framing. This technique, usually called constructive editing, remains common today as well, especially in action scenes.

While praising analytical editing, Kuleshov was particularly taken with constructive editing, because that shows that cinema can call on the spectator’s tacit understanding to assemble the separate shots. Kuleshov realized that we will build a sense of the scene’s space and action out of separate shots without need for the comprehensive view supplied by an establishing shot.

What the Americans developed, the Soviets thought seriously about. Around 1921, Kuleshov and his students mounted some experiments, several of which he discusses in his books and essays. He probably didn’t need to experiment; the American films were full of examples. Indeed, the Number Please? passage is more intricate than any experiment Kuleshov seems to have mounted. But he had a bit of the engineer about him, and he sought to break the technique into its simplest components.

For one thing, constructive editing offered production efficiencies. You could film two actors separately, at different times, and then cut them together. Further, Kuleshov saw that editing could abolish real-world constraints. It created events that existed only on the screen, with an assist from the viewer’s mind.

This is perhaps best seen in his experiment involving an “artificial person.” Evidently it wasn’t a case of constructive editing, because it seems to have begun with an establishing shot. The first shot shows a girl sitting at her vanity table putting on makeup and slippers. A series of close-ups of lips, hands, legs, and the like were derived from different women, and they were edited together to create the impression of a single woman. (Something of this effect survives in the idea of a body double in contemporary films and TV commercials.) But the point is that the woman on screen, made out of different parts, doesn’t exist in the real world.

The same possibility could apply to geography, if we delete the establishing shot. As Kuleshov describes his experiment, we initially get a shot of a woman walking along a Moscow street. She stops and waves, looking offscreen. Cut to a man on a street that is in actuality two miles away. He smiles at her and they meet in yet a third location, shaking hands. Then together they look offscreen; cut to the Capitol in Washington DC. Kuleshov saw the potential for imaginary geography as both a useful production procedure and a demonstration that editing could create a purely cinematic space, one not beholden to reality.

Kuleshov’s most famous experiment, the one he identified with the “Kuleshov effect” proper, involves a stock shot of the actor Ivan Mosjoukin, taken from an existing film. In his writing he’s rather vague and laconic about the results.

I alternated the same shot of Mosjoukin with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, a child’s coffin), and these shots acquired a different meaning. The discovery stunned me—so convinced was I of the enormous power of montage. (1)

Kuleshov’s pupil the great director V. I. Pudovkin offers a different description of the shots: a plate of soup, a dead woman in a coffin, a little girl playing with a teddy bear. He also goes farther in reporting how the audience responded. People read emotions into the neutral expression on Mosjoukin’s face.

The audience raved about the actor’s refined acting. They pointed out his weighted pensiveness over the forgotten soup. They were touched by the profound sorrow in his eyes as he looked upon the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he feasted his eyes upon the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same. (2)

Now it isn’t only geography or a human body that has been created by editing; it’s an emotion.

These experiments have been poorly documented, and only a couple have survived. One consists of fragments of the imaginary geography exercise. Here is Alexandra Khokhlova waving, but we don’t have the answering shot of the male actor responding. The two meet at the foot of a statue.

After the two shake hands, they look up and out of the frame, but unfortunately we lack the shot of the Capitol.

Kristin and other scholars have written more about these surviving fragments, and their essays are published along with Kuleshov’s proposal for funding the experiments and his wife Khokhlova’s memoir of filming them. (3)

It’s worth taking these prototypes of constructive editing apart a little bit. Clearly, there are several cues that prompt us to see the shots as continuous.

One cue is a common background, or at least a consistent one. Kuleshov thought that sometimes a neutral black background worked best, especially for close shots, as you can see with the handshake shot. Another cue is roughly consistent lighting from shot to shot. Yet another is the presumption of temporal continuity; no moments seem to be omitted in the cut from shot A to shot B. It never occurs to us to consider that Kuleshov’s man is looking at something hours or days before the soup is laid on the table in the second shot.

One of the most important cues goes unmentioned by Kuleshov: the very act of looking. Like most commentators, he seems to take it for granted. Yet it’s crucial in prompting us to imagine an overall space in which the actions take place. Knowing the real world as we do, we can infer that if you’re close enough to watch someone, both people are probably in a shared space, such as the arcade strip in the amusement park in Number, Please?

Another cue is facial expression. In his soup/girl/coffin sequence, Kuleshov supposedly picked a shot of Mosjoukin that doesn’t have a clearly identifiable expression. If Mosjoukin was smiling in his interpolated shot, he would presumably seem not grieving but wicked. Normally, though, performers seen in the single shot are expected to express the appropriate emotion more fully, in order to specify what we take the characters’ mental states to be. Our sequence from Number, Please? makes sure we understand the drama by giving the actors unambiguous expressions.

Finally, in the Kuleshov prototypes each shot should be simple. Its action can be stated in a brief sentence. A woman waves. A man responds. A man looks. A plate of soup sits on a table. Even in Number, Please? we can summarize each shot: Harold looks off. His former girlfriend disdains him. That’s to say that the shots are composed to present only one, quickly grasped point of interest.

Filmmakers don’t need to tease apart all these cues; they use them intuitively. Soon after Number, Please?, Hollywood filmmakers were creating amazing passages of eyeline-match editing—the most virtuoso being probably the racetrack sequence in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1926). Within a few years of Kuleshov’s experiments, Soviet filmmakers were creating their own masterworks, like Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Kuleshov’s By the Law (1926). Benefiting from a very compressed learning curve, filmmakers took constructive editing to new heights.

Constructive editing, dissolved relationships

Sometimes constructive editing is used to save a scene when production goes astray. When Doug Liman reshot the climax of The Bourne Identity, Julia Stiles couldn’t be on set, so singles of her taken from the first version were wedged in among the retakes, to create the impression that she was watching Jason confront his controller. More positively, a carefully calibrated constructive editing is central to a sequence I analyzed a while back in In the City of Sylvia. For over 100 shots, the spatial relations are built up without an overall establishing shot. (4)

Constructive editing can be used systematically throughout a film. A good example is Alan J. Pakula’s thriller Presumed Innocent (1990). Spoilers coming up!

Harrison Ford plays Rusty Sabitch, a prosecutor in the District Attorney’s office who becomes infatuated with a new woman on the staff. He has a brief affair with her, but after she’s broken it off she’s found brutally murdered. He has to investigate the crime without involving himself, but eventually he becomes the prime suspect.

At the start of the film before Rusty learns of the murder, Rusty and his wife Barbara are shown at breakfast, and establishing shots bring them together.

At the office Rusty learns of Carolyn’s death, and after he comes home, the conversation between Rusty and Barbara is treated without an establishing shot. Barbara knows about the past affair, and Rusty is wracked by guilt and shame. The cutting seems to reflect the fact that Carolyn’s death has revived the pain in their marriage.

In a series of flashbacks, Rusty relives his affair with Carolyn. Pakula treats their early encounters by means of constructive editing. The common-background cue is especially helpful in this scene in a kindergarten.

Only after Carolyn and Rusty cooperate and win a child-abuse case does the cutting’s rationale become clear. Pakula has saved the traditional two-shot framing for their moment of passion, as they make furious love in the office.

But soon their affair wanes and Rusty is reduced to watching Carolyn from across the street in point-of-view shots.

After the flashbacks end, Rusty is investigated and eventually charged with Carolyn’s murder. In these scenes Pakula often situates Rusty and Barbara in the same frame, as if the threat to him has healed the breach between them.

Yet in the film’s climax—and here is the big spoiler—they are pulled apart again. The last scene is a sustained monologue by Barbara. As Rusty listens, across twenty-six shots the two are never shown in an establishing shot.

Contrary to the standard Hollywood ending, in which the loving couple embrace in reunion, here they are left divided.

Pakula’s use of constructive editing has effectively traced two arcs: the growth and dissolution of Rusty’s affair, and the reuniting and dissolution of his marriage. In such ways, what might seem a purely local effect, confined to a handful of shots, can create stylistic patterning across a film. The judicious use of constructive editing matches the dramatic development.

Godard of the gaps

Robert Bresson has made more varied and complex uses of constructive editing across a film, as I tried to show in Narration in the Fiction Film and in an Artforum essay. (5) A more radical approach, somewhat in the purely Kuleshovian spirit, can be seen in Godard’s films since the late 1970s. In presenting a scene, Godard often omits an establishing shot, so constructive editing takes over. But he makes the technique quite abrasive and ambivalent.

In watching films like Number, Please? and Presumed Innocent, we fill in the gaps between shots with ease. Godard, however, makes his images and sounds more fragmentary by equivocating about the Kuleshovian cues. The background elements and lighting don’t match entirely; time seems to be skipped over; glances and facial expressions are ambivalent. Adding to these factors, lines of dialogue slip in from offscreen. Godard does present a dramatic scene taking place, but he also creates a sense that images and sounds have been pried loose from their place in an ongoing action, floating somewhat free and functioning as objects of contemplation for their own sake. The cues that Lloyd insists on and that Kuleshov plays with are ones that Godard suppresses or makes ambiguous.

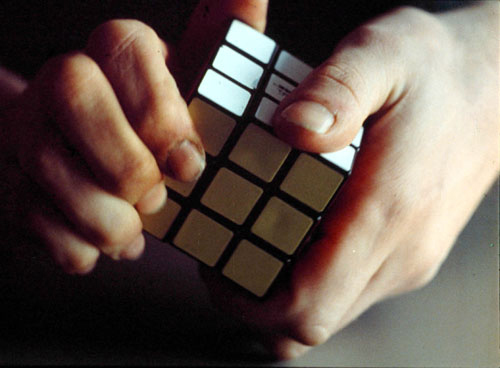

I’ve mentioned this tendency in a recent entry, but to elaborate a little, consider the science lecture in Hail Mary (Je vous salue Marie, 1985). A professor who has emigrated from an Eastern bloc country is explaining his theory that life on earth began and evolved because it was directed by extraterrestrials. No establishing shot of the classroom shows us where he, Eva, and two male students are located, so we have to construct a rough sense of their positions on the basis of a few cues. As Eva, perched on a windowsill, toys with a Rubik’s cube, we hear the professor’s lecture begin to speculate on whether life could have evolved spontaneously. His remarks about sunlight coincide with a burst of sun on her face.

After the Biblical title, “In those days,” we get a series of shots that allow us to apply our mental schema of a classroom lecture: attentive students looking off, a professor at the blackboard.

Lacking an establishing shot, we can’t specify how many people are in the class, nor indeed where Eva and her classmate are sitting—since the professor looks off in several directions during his talk.

At the end of his talk he remarks, still scanning the room, that we can presume that life exists in space. “We come from there.” At that point Godard cuts to the head of another student, seen from behind. The sproingy haircut is a little explosion of yellow, and it’s accompanied by a burst of choral music. And as the shot goes on, we start to notice that the professor is pacing in the background, out of focus.

The student, whom we’ll learn is named Pascal, asks a question (at least the slight head movement suggests that it comes from him), and the professor replies. Pascal scratches his head as the professor continues, still out of focus. If I had to choose one shot that condenses Godard’s strategy of suppression in this sequence, this shot would be my candidate.

At the end of the shot, the professor asks Eva to stand behind Pascal. Cut 180 degrees and somewhat farther back to Pascal, now seen from the front. The professor’s hand brings the Rubik’s cube into the shot and Eva comes up behind Pascal as the professor passes.

Later she and the prof will become lovers, but Godard lets them meet first as simply two torsos intersecting behind Pascal. The purpose is a demonstration that a “blind” agent can be steered toward a goal through simple yes/no commands. This models the professor’s theory that an alien intelligence could have guided evolution.

Pascal will twist the facets of the cube under Eva’s hints. Godard makes this a tactile, even erotic exchange, with the close-up of her by his ear and Eva saying, “Yes,” more urgently as Pascal’s hands arrive at a solution, in the close-up surmounting this blog entry.

The next two shots of the sequence center on the prof, who has exited frame right from the “three-shot.” Now he’s at the window, recalling the initial shot of Eva; but unlike her he’s little more than a silhouette. As crashing organ music is heard, he seems to be watching the experiment from afar. The second shot, an axial cut-in, coincides with the offscreen voice of a male student: “Were you exiled for these ideas?”

“These ideas, and others,” the prof replies. He says he’ll see the class on Monday, evoking the idea that he’s dismissing the offscreen students, and he turns his head slightly, though we can’t be sure they’re on his right. This shot will be held for some time as students quiz him more about his theory, and Eva asks him if he’d like to come over for a drink some evening. But we don’t see her say it. Godard cuts to a shot of Eva at the window, bathed in sunlight, opening and shutting her eyes as she slightly lifts and lowers her head.

As we see her, we hear the rustling of people leaving (so the class was evidently larger than three). And we hear him reply to her invitation, “That’s another story [scénario].” Are Eva and the prof looking at each other? We’re inclined to say yes, but her closed eyes and tilting head suggests someone lost in contemplation rather than engaged in conversation. Here the classic facial-expression cue is made indeterminate. We have no way of knowing if the prof’s line comes from offscreen, or is displaced from another point in time; maybe he has left the room. Such displaced diegetic sound occurs elsewhere in the film.

We don’t have to decide; our indecision is the point. By pruning away the most reliable cues, Godard wins both ways. We’re kept somewhat oriented to an intelligible action: a prof sets forth his far-fetched theory of human origins and a woman in his class invites him for coffee. This side of the balance allows us to feel that a story, however sketchy, is moving forward.

But the moment-by-moment texture of the scene allows the individual shots, gestures, and sounds to drift somewhat free. Each image takes on a more intrinsic weight, and the juxtaposition of picture and sound acquires a resonance that we usually call poetic. A shot of Eva in the sun playing with the Rubik’s cube, unanchored in time (during class? before class started?), invites us to apply metaphors, especially once we learn her name. Pascal’s thorny hair suggests not only extraterrestrials but the explosion of a nova. The silhouetted prof, detached from the mechanism he has set in motion, hints at an unknown deity watching the game play out according to his rules. Why do Godard films spawn long essays built out of erudite associations? Because the narrative progression relaxes and we can weave our own connotations out of what we see and hear.

If you don’t want to go down the expanding-association route, there’s another one open. When individual moments no longer accumulate ordinary dramatic pressure, we can savor the fugitive pleasures of the separate shots (light on face, lips by ear) and the patterns they form: flipover cuts, yellow hair and yellow facets, bookended shots of Eva at the window.

Those patterns, it should be clear, depend on our sensing a bump at every shot change, looking for a way to skip across the gap that Godard creates. The same belief that meaning and effect are born of gaps impelled Kuleshov too, and perhaps even Lloyd. If we pay attention to those gaps we can feel minds—both the filmmaker’s and ours—at work in them.

(1) Lev Kuleshov, “’50’: In Maloi Gznezdinokovsky Lane,” Kuleshov on Film, trans. and ed, Ronald Levaco (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1974), 200.

(2) V. I. Pudovkin, “The Naturschchik instead of the Actor,” Selected Essays, ed. and trans. Richard Taylor (Oxford: Seagull, 2006), 160.

(3) See Kristin Thompson, Yuri Tsivian, and Ekaterina Khokhlova, “The Rediscovery of a Kuleshov Experiment: A Dossier,” Film History 8, 3 (1996), 357-367.

(4) The sequence does begin with a long shot of the café, but it is so distant, crowded, and brief that it can’t really be said to establish the spatial relationships among the several characters we see.

(5) “Sounds of Silence,” Artforum International (April 2000): 123.

Watching movies very, very slowly

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.