Archive for the 'National cinemas: South America' Category

Vancouver 2019: Tales of oppression and resistance

Bacurau (2019).

Kristin here:

Examinations of social problems and portrayals of downtrodden people are fertile ground for makers of art cinema. This year’s festival saw many films from around the world tackling such subjects in original ways. Here are four impressive instances.

Castle of Dreams (2019)

Reza Mirkarimi is one of Iran’s top filmmakers, with three of his films having been put forward as Iran’s nominee for an Academy Award. In Castle of Dreams he has created a sort of nightmare version of the traditional child-quest tale so popular when Kiarostami and Makhmalbaf were at the heights of their careers. The protagonist, Jalal, has recently been in jail. The film opens as he is making some sort of a deal by telephone. His wife has just died after a protracted illness, and his sister-in-law, who had been taking care of Jalal’s two young children, is forced by her husband to turn them over to Jalal. But he clearly wants nothing to do with them.

Jalal sets out with them in his late wife’s car, picking up his Azeri fiancée on the way to Azerbaijan. He continuously snaps at the small children, Sara and Ali, and at his fiancée. It eventually comes out that he had taken his wife off life support and sold her heart for transplant, all without telling her brothers. Despite his occasional clumsy attempts to be kind to the children, any expectations that the audience may have that he will be charmed by them and transform into a responsible father are far too optimistic.

If this were a traditional child-quest plot, Sara and Ali might struggle to get back to their kindly aunt. Here, despite becoming increasingly miserable as Jalal’s full villainy is revealed, they are essentially prisoners in the back seat of the car (above). Ultimately the film takes a clear-eyed, realistic view of the future for this little family.

The acting carries much of the film. Hamed Behdad won a best-actor award at the Shanghai International Film Festival (where the film also won the best-picture prize). The child actors are charming and elicit considerable sympathy for their plight.

Song without a Name (2019)

Inspired by a real-life case that her journalist father investigated, Melina León’s first feature successfully generates sympathy for her two main characters and recalls the horrors of the past. Set in 1988, it follows Georgia, a pregnant indigenous woman living in a shack near the sea and scraping by as a street-seller of potatoes (above). Lured in by a radio ad, she visits a free clinic with a reassuring name, the “Saint Benedict.” The organization is anything but benevolent, however, spiriting her newborn daughter away for “check-ups.” Desperate to find the baby, she and her partner Leo encounter only indifferent police and other other government officials.

Eventually she finds a sympathetic helper in Pedro, a reporter who confidently promises that they will recover her baby, despite the fact that it has most likely been spirited out of the country for adoption. While Pedro pursues his investigation, Georgina finds her ability to purchase wholesale potatoes shrink in the face of rampant inflation, on top of which she discovers that Leo is apparently a member of the Shining Path terrorist group. Pedro meanwhile starts an affair with a gay actor in his apartment block, only to be threatened with exposure and death, presumably by the gang that runs the baby-stealing operation.

The film will inevitably be compared to Roma, even thought the films have nothing substantive in common. Both are black-and-white, Latin American films, and both heroines are pregnant; that’s the extent of the resemblance. León’s film has nothing of the nostalgia that permeates Roma, and Georgina is far more marginalized and downtrodden than Cuarón’s heroine.

León also is working with a far smaller budget and yet with the help of cinematographer Inti Briones she has fashioned a sophisticated and lovely film. One lengthy shot is particularly impressive. In it Pedro meets with a potential witness in a small motor boat. The camera, in another boat, catches it as a pulls away from the dock and glides around it as it turns,

The camera moves rightward with the boat but also moves in to show the woman sitting, apparently alone, in the boat.

A move further away establishes that Pedro is present, and we watch as the woman walks forward to sit beside him.

As she warns him of the danger of pursuing the kidnapping gang, the camera moves slowly in to emphasize her revelation that years before she had sold her baby to them

All the while the huge shantytown glides past in the background, emphasizes the extent of the poverty in the outskirts of Lima. The choreography of camera and action in this two-minutes-plus shot could hardly be bettered in a production with many times the budget. (A clip of this long take is currently posted on Youtube.)

The title seems to refer to the lullaby that Georgina sings, just calling her lost child “baby” because she never was given a name.

The film played in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes, where it received positive reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter. It deserves further festival play, and we can hope that León can follow up with other films.

Sorry We Missed You (2019)

Then there is, Ken Loach, the veteran English filmmaker who continues to deal movingly with the plight of working-class people. In Sorry We Missed You–which deceptively sounds like a title for a comedy–tackles the gig economy and its grinding effect on one industrious couple and their children.

The inevitability of bad consequences seems obvious as the husband of the family, Ricky, agrees to become a driver for an express delivery service which transports packages for the likes of Amazon and other online sellers. He is not an employee but an independent agent, the supervisor emphasizes. Buying his own van supposedly will cost less than leasing, so he sells the family car for a down payment. His wife Debbie, a caregiver for home-bound elderly and handicapped people, is forced to take the bus to her widely scattered clients.

The couple’s long hours begin to tell on their teen-age son, who is turning into a school-skipping, graffiti-spraying delinquent, and their younger daughter, who is crushed by the stress of watching her family falling apart.

Loach is expert in depicting the challenges of such a job, from the pressure for drivers to load packages onto the van rapidly (bottom) to Ricky’s indecision over whether to risk a fine for illegal parking or deliver a package late (above). As he misses deadlines and skips work over family crises, the company’s sanctions and fines begin to accumulate. Ricky spirals into debt. Debbie, torn between duty to her family and the people who depend on her, faces similar problems in dealing with her helpless clients.

There is no happy ending here, though there is some suggestion that the dire situation of the family at least forces them to try and help each other out. Loach has created a plausible, gradual descent into near despair. He portrays the pressures of large companies and organizations that expect much of their “independent contractors” but offer little support in return.

Bacurau (2019)

At first glance, Bacurau represents a considerable departure from Kleber Mendoça Filho’s two previous films, both of which we saw at VIFF, Neighboring Sounds and Aquarius. Both dealt with unscrupulous methods used by real estate dealers to push people out of older neighborhoods to make way for gentrification. Now, co-directing with Juliano Dornelles (the production designer on the two previous films), Filho departs from the big city for a small village in the wilds of northern Brazil. The village, by the way, is imaginary, a fact that provides a running joke about the characters’ inability to find it on maps.

Someone in power wants the villagers to leave, again to make way for the exploitation of the land for undisclosed purposes. In a way, it’s not such a departure from the previous films as it seems. Blocked water sources and inadequate food deliveries have failed to budge the villagers, who make do on their own. The film opens with two villagers in a tanker truck full of water bound for Bacurau (above).

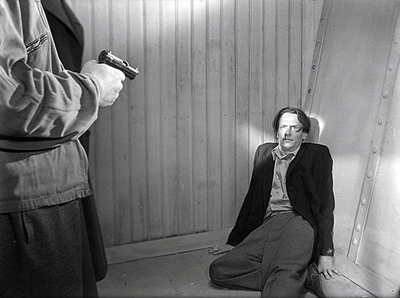

Having failed to uproot these determined peasants, the unseen power has brought in a group of wealthy hunters who are keen to gun down human beings and have been given carte blanche to exterminate the entire village. Delivery trucks appear with cargoes not of food but of dozens of empty coffins, a few of which are soon used for the first victims of the hunters (see top).

Despite the suspenseful and sometimes gory action, the film has considerable humor. It soon turns into a modern version of the politically charged Cinema Novo films of Brazil in the 1960s and 1970s. The peasants prove less helpless than they initially appear, and soon the hunted are hunting their hunters.

By this point members of the audience with whom we saw the film were cheering, and obviously there was a contingent of Brazilian speakers who got some jokes that we didn’t.

All in all, it’s a wild, entertaining film, though not for the faint of heart.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

Sorry We Missed You (2019).

Vancouver 2018: A final few films

Kristin here:

As I write, David and I have been at home after the Vancouver International Film Festival for one week. Between Venice and Vancouver, I saw about 40 films, some of them likely awards competitors for the year and some more modest works that need to be sought out at festivals and big-city art-houses. (Today, in a cyclical gesture, we’re going back to the very first film we saw at Venice, First Man, this time in IMAX.)

During any festival there’s never time enough to write up comments on all the films we see. This is our last report on the 2018 Vancouver event, this time dealing with Middle Eastern films and one from South America.

3 Faces (Jafar Panahi, 2018)

3 Faces begins startlingly, with a vertical cell-phone image of a girl in a rocky area, dictating a suicide note as she walks. She identifies herself as Marziyah, a peasant girl who aspires to be study acting but whose conservative family (along with their entire village) have blocked her from doing so. She has written repeatedly to a famous TV actress, Behnaz Jafari (played by herself) for help, but receiving no response, she has decided to kill herself. The recording ends as the girl apparently hangs herself and the camera falls.

The image opens to fullscreen as Jafari, riding in a car with Panahi, watches the recording, distraught at the possibility that she has failed to help the girl. She also wonders whether Marziyah has really killed herself. Was the film edited to create that impression? Panahi thinks it looks authentic, and he drives Jafari out to the girl’s village to find out.

3 Faces is the fourth feature Panahi has made since his trial in 2010 and the resulting sentence banning him from filmmaking for twenty years. We had been following his career before that, most notably with The Circle and Offside. In happier days, David met Panahi briefly at the Hong Kong Film Festival, when they sat next to each other at an award ceremony. David posted an account of Panahi’s charges and sentencing in 2010. We have also written about films that Panahi has made since then: This Is Not a Film and Closed Curtain. Somehow, though we saw Taxi, we didn’t blog about it. Today Panahi remains unable to leave Iran to attend the festivals where his films are honored (3 Faces won the best-screenplay award at Cannes), and he has no access to studio facilities.

With 3 Faces, Panahi has moved on from making films about his plight and looks at the repression suffered by women and girls in the rural areas of Iran.

This time he follows the classic quest pattern of many of the golden age of Iranian cinema from the 1980s to the early 2000s. 3 Faces is perhaps most reminiscent of Kiarastami’s And Life Goes On, another director’s journey to the countryside to check on a child who may have died. It’s gratifying to see the fruitful quest pattern revived, and Panahi creates a work that is at once familiar and uniquely imaginative. The settings, mostly in Panahi’s car and the countryside of Iran near the Turkish border.

As in other such films, 3 Faces is as much about the unexpected encounters with strangers along the way: a wedding group celebrating on a steep mountain road, a woman testing out her own grave to make sure it’s comfortable, an old man who introduces Panahi to the patterns of honks locals use when approaching each other on the narrow roads. Upon reaching the village and encountering Marziyah’s family, it becomes apparent that they are baffled and annoyed by the girl’s ambitions to devote herself to a frivolous career rather than marry and settle down.

Jahari also encounters a retired actress from before the 1979 revolution, Shahrazade, now a recluse living in a tiny house near the village (see top). The “3 Faces” title apparently refers to the three generations of actresses, Shahrazade, Jafari, and Marziyah. This explanation is not apparent from the film, especially since Shahrazade is glimpsed only in extreme long shot from the back as she paints in a field.

Panahi has made a more acerbic film than those of Kiarostami, poking fun at the villages and especially emphasizing the way the men are obsessed with virility and controlling their womenfolk. Receding into the background despite his major role, Panahi takes p the feminism he displayed in Offside and reveals the more serious lack of freedom women and girls experience in rural areas. He does so without abandoning the humor that underlies many of the quest films.

Kino Lorber will distribute the film in the US, with a release planned for March, 2019.

Dressage (Pooya Badkoobeh, 2018)

Another trend in recent Iranian cinema might be termed the Farhadi effect. Asghar Farhadi has become the most prominent of the current group of Iranian directors, winning best foreign-language Oscars for both A Separation and The Salesman. His films tend to center around a serious mistake or a crime committed early on, with the varying reactions of the characters forming the bulk of the drama. In some cases sudden twists reveal motivations that tend to make the situation more ambiguous morally, and the rights and wrongs of the situation do not resolve clearly.

Dressage, Badkoobeh’s first feature, fits this pattern to some degree. A group of middle-class and upper-middle-class students are in the habit of robbing shops for thrills. As the film opens, they have robbed a small grocery store. When a clerk who lives in the store unexpectedly interrupts them, their leader knocks him out. Having fled, the group discovers that they have neglected to take the incriminating surveillance tape with them. The protagonist, sixteen-year-old Golsa, is sent back for it. Having retrieved it, she hides it in a bin at the stables where she helps take care of expensive dressage horses (above).

Golsa refuses to turn over the tape, either to the group or to her parents, all of whom wish to destroy the evidence. What Golsa plans to do with the tape is unclear, but she is subjected to more and more pressure to give it up. Along the way, her stubbornness begins to harm the very working-class people, such as the store clerk, whom she hopes to help.

The rather simple story is given some depth by Golsa’s love for one of the dressage horses. It’s made clear that such horses are valuable and must be exercised without letting them run free, which would risk damage to their legs, but at one point she takes her favorite into a field to frolic about.

Ultimately the film has less of the complexity and ambiguity of a Farhadi film, but it shows promise for a younger generation of Iranian filmmakers.

As far as I can determine, Dressage does not have a North American distributor.

Caphernaüm, aka Capernaum (Nadine Labaki, 2018)

I remember that during the Cannes festival, Kore-eda’s Shoplifters and Labaki’s Capernaum were among the films most often predicted to win the Palme d’Or. In the event, Shoplifters took the top prize, and justifiably so, and Capernaum received the Jury Prize, the second highest honor. Both films center around families living in poverty, though Shoplifters moves among the members of its family and emphasizes their mutual support. Capernaum, on the other hand stays resolutely with Zain, the 12-year-old boy who is so miserable that he takes his parents to court to sue them for having brought him into a wretched existence in the Beirut slums.

Labaki, determined to expose the reasons for the sufferings of children in the poorer areas of Beirut, spent three years researching the subject. She cast actual slum-raised children rather than actors and coaxed remarkable performances from them. It seems absurd to speak of a performance from the one-year-old girl who plays Yonas, the little boy whom Zain struggles to care for when the toddler’s Ethiopian-emigré mother is arrested for lack of proper papers; still, the child seems always to be doing exactly what is natural and appropriate for the situation. The result of working with non-professionals and children was 500 hours of footage to be edited down into a two-hour film. (The production information is from an interview with Labaki in The Hollywood Reporter.)

It seems churlish to find fault with Capernaum, which certainly must be given credit for exposing a side of life that most viewers will never witness. It mixes humor and pathos with a deft hand and is undoubtedly entertaining and thought-provoking. Yet there are moments when the film’s effort to tug at our heartstrings seems a bit too obvious and overdone. Some critics have been unqualifiedly moved by the film, while others find it a bit too manipulative. I suspect that most audiences who see it in art-houses in the US will share the reaction of the Cannes audience, who gave it a 15-minute standing ovation.

The meaning of the film’s title is intriguing, and some clarification might be helpful. I have given both its original Lebanese title, Capharnaüm, and the one used in English-speaking countries, Capernaum. They are variant spellings of the same word, but with different meanings. “Capharnaüm” is French and means “a confused jumble” or “a place marked by a disorderly accumulation of objects” (Merriam-Webster). It derives from the Aramaic spelling of the Hebrew name Capernaum, the village on the Sea of Galilee where Jesus is said in the Bible to have been based during most of his ministry.

The “confused jumble” derives from the large crowds that flocked around Jesus, as in Mark: 1-2:

And again he entered into Capernaum after some days, and it was noised that he was in the house.

And straightaway many were gathered together, insomuch that there was no room to receive them, no, not so much as about the door; and he preached the word unto them.

Labaki, being a Catholic (belonging to the Lebanese Maronite Church and having been educated at St. Joseph University in Beirut), would surely have been aware of both these meanings when she made her film. The notion of a crowded jumble applies well to the environments in which the children in the film live. Certainly the children belong to the downtrodden classes to whom Jesus ministered. Possibly the reference to Jesus’ miracles, several of were reportedly performed in Capernaum, helps to justify the implausibly upbeat ending of the film.

Capernaum will be released in the US by Sony Pictures Classics on December 14.

Birds of Passage (Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018)

Birds of Passage is the first film directed by Ciro Guerra since his excellent Embrace of the Serpent, which was the first Colombian film nominated for a foreign-language Oscar. This time he co-directs with his wife and producer, Cristina Gallego.

Birds of Passage is a very different film from Embrace of the Serpent. The latter is set in the Colombian Amazon region, focuses on the decimation of indigenous peoples by the rubber trade, is shot in black and white, and cuts between two time periods decades apart involving two explorers guided by the same indigenous guide. Birds of Passages is set in a desert region of northern Colombia, deals with the early effects of drug-trafficking among the Wayuu people of the area, is shot in color, and follows a single extended family chronologically through five periods between the 1960s and 1980s, each announced by a dated title.

The result is a plot that is much easier to follow than that of Embrace of the Serpent. While the earlier film was based around the evocative, mysterious hunt through the jungle for a fictional sacred plant, Birds of Passage is very much anchored in the history of the early marijuana trade that the central family becomes involved in, growing very rich in the process.

In the film, the first American customers who draw the ambitious hero, Raphayet, to obtain a small amount of marijuana for them are some Peace Corps volunteers. Soon criminal traffickers become customers for Raphayet’s wares, and the roughly two decades of drug-running that follow balloon into a business that ends with a war within the family (see bottom).

The title refers to a motif that is introduced in the opening scene, when teenage Zaida, of the foremost family among the Wayuu, finishes her official transition to womanhood with a ritual dance based on bird mating rituals. Raphayet offers to dance with her (above), and the task of meeting her mother’s high dowry price includes him making his first small drug deal. The motif of real birds continues, but migrating “birds of passage” is also a local term for the American traffickers who fly in and out in small planes, bringing money in such large bundles that have to be weighed rather than counted.

As a film, Birds of Passage is not as challenging or evocative as Embrace of the Serpent. Its fascinating story, however, deals with the little-known history of the origins of the South American drug trade, the growing problem that has caused such upheaval in the region and is very much still with us.

The Orchard has the US rights, with no announced release date.

Returning for a moment to the Venice International Film Festival, three publications generated by the 2018 festival are now available for sale.

Two of these publications result from the festival’s 75th anniversary this year. Peter Cowie’s Happy 75º: A Brief Introduction to the History of the International Film Festival offers a succinct, chronological account of the festival’s facilities, organizers, guests, and winners year by year. Reading it enlivened the time spent in line before films for both David and me.

The festival also presented a large exhibition of photographs, again presented year by year, celebrating the films shown and the stars attending. This exhibition was mounted in the legendary Hotel des Bains, closed in recent years but formerly housing many of the festival’s glamorous guests. It is mainly connected in the minds of most moviegoers with Visconti’s Death in Venice, which was filmed there. There are plans to renovate and re-open it. A large catalog containing what appear to be all the photographs from the exhibition has also been published.

Finally, this year’s program, with extensive notes on the films, is available.

All of these can be ordered from amazon.it. The program can also be downloaded.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help during our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Birds of Passage

Bye bye Bologna

Lucky to Be a Woman (1955).

DB here:

How to sum up nine days of Cinema Ritrovato? I logged thirty-two features and half as many shorts and fragments, along with a few panels and workshops. Fate cursed me with the need to blog and to sleep, so I missed many prime items. And that’s including my (sad) decision not to revisit films I’d already seen, so I sacrificed new exposure to masterpieces from Ozu, Mizoguchi, Feuillade, Leone, de Sica, etc.

In this last Bologna roundup, all I can do is wave at some of the surprises and discoveries that captivated me.

Many of my pals praised the Mexican noir Western Rosauro Castro (1950), which I had to miss, but I did get compensated by Prisioneros de la Tierra (1939), an Argentine classic of romantic realism. The plot concerns the exploitation of peasant migrants forced to work in dire conditions. One scene, of a drunken doctor in the throes of the DTs, got a rise out of Jorge Luis Borges.

Even more shocking was the red-light melodrama Víctimas del Pecado (1951, above) by the great Emilio Fernández. A newborn baby dumped into a garbage can; a preening, sadistic pimp who can smoke, chew gum, and dance frantically at the same time; a nightclub dancer who tries to live righteously but winds up in prison for her pains; and several splashy music numbers–who could resist this? Not the Bologna audience, who burst into applause when, after slapping a child silly, said pimp got a quick and violent comeuppance. Of course the gorgeous cinematography of Gabriel Figueroa contributed a lot: One shot of a train blasting black smoke into the night would be enough to exalt a far less delirious movie.

Thanks to Dave Kehr of MoMA, who brought a sampler from his recent Fox retrospective, and to UCLA and other sources, aficionados of American studio cinema had no shortage of delights. Monta Bell’s Lights of Old Broadway (1925) gave Marion Davies a dual role as twins separated at birth and she made the most of half of it, playing a no-nonsense colleen who makes it big at Tony Pastor’s. Part of the fun was the film’s historical references: Teddy Roosevelt as an undisciplined schoolboy, Weber & Fields as a kiddie act, and a solicitous Thomas Edison urging the heroine to invest in electricity.

Ten years later, One More Spring (1935, above) from Henry King offered a gentle seriocomic Depression tale. Two homeless men squatting in a garage take in a woman who sleeps on the subway, and they try to make ends meet with the help of a kindly old couple. At first engagingly episodic in the McCarey manner, the plot gets more tightly bound when the old couple faces the loss of their savings. Janet Gaynor is endearing, as usual, and Warner Baxter brings his clipped energy to the role of a hopelessly optimistic failure. There are no villains. The banker struggles to save his depositors, though he’s frank enough to admit, “It’s all the fault of the Republicans. Still, I’ll vote for them in the next election. With the Democrats you never know what to expect.” Another big laugh from the crowd around me.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

That Brennan Girl (1946) exemplified the opportunities that the boom in 1940s moviegoing offered downmarket studios. Apart from the second-tier cast and the warning “Not Suitable for Children,” the production’s B-plus aspirations were clear, yielding a surprisingly polished Republic picture (buffed up by a beautiful Paramount restoration). A woman raised by a predatory mother takes up petty theft and con games. She reforms, but after becoming a war widow she falls back into her old ways–endangering her baby in the process. That Brennan Girl could have served as an example in my Reinventing Hollywood book, since it flaunts a long flashback punctuated by dreams and bits of imaginary sound. Those narrative stratagems pervaded films at all budget levels.

Another 1940s technique was the chaptered or block-constructed film, Holy Matrimony (1943), a genial comedy about switched identities, contains sections with titles like “But in 1907” and “And so in 1908.” The film, about a painter brought back to London from his tropical hideaway, reworks the Gauguin motif made famous by Maugham’s Moon and Sixpence (1919). Was this release an effort to build on Albert Lewin’s 1942 version of the novel? Monty Woolley plays himself, but Gracie Fields brought real warmth to the clever, ever practical woman who marries him.

Holy Matrimony was a welcome, if minor entry in the John Stahl retrospective. I had to miss the much-praised When Tomorrow Comes (1939) but was happy to break my rule of avoiding things I’d seen before when I had a chance to revisit Imitation of Life (1934). I persist in thinking this better than the Sirk version, not least because of its harder edge. Beatrice Pullman’s exploitation of her servant Delilah’s pancake recipe carries a sharp economic bite, and the brutal classroom scene yanks our emotions in many directions. (While Peola writhes in her seat, her mother asks innocently, “Has she been passin’?”) As in Stahl’s other 1930s efforts, his studiously neutral style is built out of profiled two shots in exceptionally long takes.

Ritrovato has always done well by its diva films, under the curatorship of Marianne Lewinsky. (They’ve just released a hot-pink box set of four classics.) In tribute to 1918 there were several star vehicles. I’ve already mentioned L’Avarazia (1918), an installment in a Francesca Bertini series devoted to the seven deadly sins.

Another high point was La Moglie di Claudio (1918), an exemplary tale of excess. When a movie starts by comparing its heroine to a spider, you know she means trouble. Cesarina (Pina Minichelli) two-times her husband, has an illegitimate child, flirts relentlessly with her husband’s protégé, collaborates with spies, and steals the plans to the cannon the husband has designed. She does it all in high style. As she dies, she falls clutching a window curtain.

In a fragment from Tosca (1918), we got a quick lesson in the illogical powers of cinematic composition. Tosca (Bertini again) visits her lover Mario in prison. Their furtive conversation is played out while the shadows of the guards come and go in the background. That’s a source of some suspense for us.

And for the couple as well. Instead of looking left at the offscreen window itself, which they could easily see, they–like us–turn to monitor the silhouettes.

It’s a nice variant on the background door or window so common in 1910s film.

Of all the surprises, the biggest for me was This Can’t Happen Here (aka High Tension, 1950), an Ingmar Bergman thriller. You read that right.

This Cold War intrigue shows spies from Liquidatsia (you read that right too) infiltrating a circle of refugees living in Sweden. The first half hour is soaked in noir aesthetics, with men in trenchcoats glimpsed in bursts of single-source lighting. The preposterous plot gives us a briefcase full of secret papers, attempted murder by hypodermic, torture scenes, and enemy agents acting impossibly suave at gunpoint. A cadre meets in a movie theatre playing a Disney cartoon, with Goofy’s offscreen gurgles punctuating an informer’s confession.

Bergman forbade screenings of the film, but Bologna was given the rare chance to reveal another side of his obsessions with brooding solitude and the pitfalls of love. Peter von Bagh’s illuminating essay included in the catalogue rightly emphasizes how in This Can’t Happen Here murder becomes the natural outcome of an unhappy marriage.

My visit was topped off by the charming Lucky to Be a Woman (1955) in the Mastroianni strand. Sophia Loren, looking like a million and a half bucks, plays a working girl accidentally turned into tabloid cheescake. Mastroianni is a louche photographer who can make her career. Bantering at breakneck speed, they thrust and parry for ninety-five minutes, all the while satirizing modeling, moviemaking, and the itchy palms of philandering middle-aged men. Mastroianni spins minutes of byplay out of an unlit cigarette, while La Loren plants herself like a statue in the foreground, facing us; if Marcello’s lucky, she may address him with a smoldering sidelong glance.

What’s not to like? After thirty-two years, Ritrovato’s magnificence is unflagging.

As usual, thanks must go to the core Ritrovato team: Festival Coordinator Guy Borlée (with appreciation for help with this entry) and the Directors (below). They and their corps of workers make this vastly complex celebration of cinema look easy. It’s actually a kind of miracle.

Ehsan Khoshbakht, Cecilia Cenciarelli, Mariann Lewinsky, and Gian Luca Farinelli.

Venice 2017: Martel’s drama of expectations

Kristin here:

Lucrecia Martel’s Zama (pronounced “sama”) happened to be only the third film we saw at the Venice International Film Festival, on the evening of its first day. As the credits faded, David asked, “Have we just seen a masterpiece?” Neither of us doubted that we had, and we suspected that we had also watched the best film we would see during the entire festival. Of course, we haven’t seen every title on offer here, but having just come back from my twenty-fourth and final film, I don’t doubt that it is.

It is also a challenging film, which we watched a second time to try and grasp the basics of what plot there is. Those of us who admired Martel’s earlier work, particularly The Headless Woman (which we also felt compelled to watch twice, this time at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2009 and wrote about here), had looked forward to her follow-up film. It was eight years in coming, and it is quite different from her earlier films in several ways.

First, while the three earlier features are set set in modern middle-class milieus, Zama is a period piece. The others had original screenplays, written or co-written by Martel, but Zama is based on a 1956 novel by Antonio Di Benedetto (translated into English in 2016). Martel was also working with a higher budget here, one which required patching together many sources of financing. The result is a co-production involving, Argentina, Spain, France, the Netherlands, the USA, Brazil, Mexico, Portugal, Lebanon, and Switzerland and a patchwork of sixteen companies. At the press conference (below) Martel said that the long gap between films was not occupied with making all these arrangements and with shooting the film, which was actually a reasonably short process. She did make a few short films during this time and was ill enough to cease working for a while.

The result of the film’s elaborate production situation is not a typical historical epic. There are impressive landscape shots in some scenes, but no uniformed crowds and grand buildings. No vast battles take place; instead there are a few small skirmishes. The bulk of the action takes place in a ramshackle group of buildings thrown up to house the Spanish colonial government of the provincial town of Asunción, already in decline by the 1790s. The money clearly was spent on creating authentic costumes and furnishings, as well as transporting the cast and crew to locations in Paraguay.

Frustrations of a colonial bureaucrat

Lola Dueñas (Luciana), Lucretia Martel, and Daniel Giménez Cacho (Zama).

We quickly learn the story’s basic premise, that Don Diego de Zama is an official stationed in this backwater town and that he fervently longs to be transferred to a more important city–ideally where his wife and children live. He is not in charge of this outpost but serves under a governor whose request to the Spanish crown is necessary for such a transfer.

We are certainly not invited to like Zama when we first meet him. The first shot shows him standing and looking down the river (see top). We later learn that he was probably watching for the boat carrying mail, which he hopes will include a letter from his wife or some official news concerning his situation. He spies on some naked indigenous women smearing themselves with mud, and when they taunt and chase him, he turns on one and slaps her viciously. In the second scene he presides over the torture of a young man who refuses to divulge some unspecified information the governor needs.

As the action proceeds, however, we witness the countless little frustrations, embarrassments, bafflements, slights, and misfortunes that Zama seems to experience constantly. A brandy merchant who arrives with his wares, seemingly one of Zama’s few friends (below), dies suddenly of the plague. Luciana, a wealthy local beauty, teases him with suggestive conversation but ultimately takes a younger man as a lover. A new governor’s arrival hints that Zama is back to square one as far as his hopes for a transfer are concerned. The man takes over Zama’s modest home and office, leaving him to haul his sparse furnishings to a barely habitable inn. When no letter from his wife arrives, Zama imagines a conversation with her in which they lament the long delay in their reunion, though we must suspect that her failure to correspond means that she has given up on him. Through all this we come to sympathize with him. We never learn how long he has been in this posting, but when someone asks he replies glumly, “a long time,” and we believe him.

Zama might seem at first to be the epitome of a goal-oriented protagonist, but he is hardly the striving, active Hollywood-style hero. There is nothing he can do to better his current situation or to further his desire for escape. Instead, the action consists of one new, often bizarre challenge after another, creating situations that simply play out, usually to no conclusion. None of these situations furthers Zama’s cause. Gradually we become aware that he is actually losing ground, as when the new governor reveals that he must write not one but two letters to the king, a process that could take a year or two. The final portion of the film takes him in a radically new direction as he tries one desperate bid to gain stature and perhaps his long-delayed transfer, a bid that only leads to worse troubles for him.

There is little sense of how much times passes in the course of this accretion of frustrating incidents. During the press conference (above), the cinematographer Rui Poças and Martel said that they sought a visual way to convey a sense of Zama’s agonizing wait, a way to give “the sensation of time that has stopped,” as Martel put it. They deliberately avoided some of the conventions of historical films. One of these was to eliminate fires and candles. Martel added, “In order to be able to think, you must be deprived of things.” This rule was strictly obeyed, with one shot that turned out to contain a candle flame in the background being eliminated. When one thinks about it, lamps, candles, and fireplaces tend to figure quite prominently in suggesting the past in films, which became particularly evident, for example, when a great deal of fuss was made about the new ability to shoot dark scenes only by candlelight in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon (1975).

Thinking, being deprived of things

As Martel also pointed out, the original novel was told in the first person by Zama, with few descriptions of locales or nature. The film opens the tale out with the occasional landscape views in the early portions and a move into a savanna setting for its last stretch of action (see bottom). For much of the film, however, Martel uses the style I described in The Headless Woman, ” shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus.” We stay almost exclusively with Diego, scanning his face for his reactions, so that the film becomes a psychological study, though the title character is a man who manages to carry on by keeping his thoughts and emotions well hidden.

Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho gives a remarkable performance as Zama. We soon realize that the character has very little understanding of the bizarre things that happen around him and of the attitudes that other people have toward him. At times he adopts the faintest of smiles, ready in case what is being said to him is supposed to be amusing. More often he looks mildly worried, as if expecting another mocking remark or revelation of some new indignity to be offered. In his court his face could be taken to convey an appropriate dignity and wisdom (below), but it might just as well be puzzlement over the case before him. With Luciana he seems passive, but his face conveys hints of lust, hope, and an anticipation of ultimate rejection. In a meeting with a superior official, he struggles to ignore the ludicrous presence of a llama (which we had seen outside when he arrived) wandering around the office behind him as he pleads his case.

All in all, despite the fact that Cacho’s craggy, earnest face seems to suggest competence, we emerge from the film with no real sense of whether Zama is in fact competent and unfairly treated or simply a man out of his depth who deservedly remains stuck where he is.

One extraordinary moment which I cannot resist mentioning comes late in the film when a horse in the foreground of a scene turns and looks directly into the lens (top of this section). Its stare is even more enigmatic than Zama’s face, just another little mystery that Martel provides.

It is not surprising that Zama was the first in a series of three novels that have come to be called Di Benedetto’s “Trilogy of Expectations.” The second, El silenciero (1964), and third, Los suidicas (1969), share no plot elements with Zama but are thematically linked to it. It is also not surprising to learn that the novelist first read Kafka in 1954, just before writing Zama.

Guy Lodge, in his enthusiastic review for Variety, refers to Zama‘s “unjust placement in a non-competition slot at Venice.” It has garnered quite a few reviews as laudatory as Lodge’s, as well as a few which dismissed it as cryptic and not engaging. A good summary of the coverage, regularly updated, is provided by David Hudson. The film deserves to gain a higher profile in its upcoming screenings at the Toronto and New York festivals. Perhaps it will also pick up a North American distributor. Somehow it should be made available on home video (Criterion, perhaps?), since this is going to be considered a classic.

The most detailed account of Di Benedetto’s life and work available online is an essay by the translator of the English-language version, Esther Allen.

Again, we are grateful to the Mostra and those who serve it, particularly Alberto Barbera and Michela Nazzarin. Thanks as well to Peter Cowie and David’s colleagues on the Biennale College Cinema panel, who have all been good company.

[October 1, 2017: Argentina has chosen Zama as its nomination for best-foreign-language Oscar. I doubt it will make it into the final five, given how challenging it is. Still, maybe it will, and in any case, it’s good to see Martel getting respect in her home country.]

[October 16, 2017: Strand Releasing picked up the North American distribution rights for Zama last month, shortly before its American premiere at the New York Film Festival. It plans a theatrical release in early 2018.]