Archive for the 'National cinemas: South America' Category

Refutations of the death of cinema, courtesy the VIFF

Maliglutit (Searchers)

Kristin here:

About three weeks ago David pointed out that the “death of cinema” being bewailed by many critics and pundits was based largely on the disappointments of the summer of Hollywood blockbusters. Taking a larger perspective, the cinema looks to be thriving. Herewith some further evidence as we continue to enjoy the rich schedule of screenings at the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some of these films are good, some very good, some perhaps great and destined to be watched for decades to come.

Maliglutit (Searchers)

In 2001 the first Inuit-made feature film, Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner won the Golden Camera at Cannes. Admirers of it, among whom we count ourselves, have wondered whether there would ever be a follow-up. Since Antanarjuat, director Zacharias Kunuk has had an active career in documentaries. Now, however, he has returned with a second fiction feature, Maliglutit (Searchers).

The title proclaims the film’s inspiration: John Ford’s The Searchers. Kunuk wanted to make a western, but one “made entirely the Inuit way.”

From the start, I resolved to anchor the production in my home community of Igloolik. It was important to get the faces right. I brought on Natar Ungalaaq, who played the lead in “Atanarjuat – The Fast Runner,” as co‐director to work with the actors preparing their performances and to mentor a new generation of Inuit filmmakers. Our cast and crew included regular collaborators, but also a number of new people in training.

Igloolik is a small island in the Northwestern Passages, far to the north in Canada. It’s population is about 2000. An extraordinary place for such important films to come from.

Maliglutit can hardly be said to be a remake of Ford’s film. Its borrowing from The Searchers is solely the kidnap plot. The hero is Kuanana, whose wife and daughter are carried off on dogsleds by four members of a neighboring tribe, led by Kupak. Kuanana and his son give chase. Unlike in The Searchers, there is no conflict between the older and younger men. Unlike Ethan Edwards, who is revealed to be hunting down the tribe who kidnapped Debbie in order to perform a sort of honor-killing, Kuanana simply wants the women back. The psychological complexities of The Searchers are replaced by a focus on the details of Inuit life in 1913 (an era in which firearms were starting to replace traditional weapons, above) and the frightening beauty of the bleak late-winter landscapes through which the chase progresses. The two women resist and seek to escape during the entire chase, and they play an active role in the climactic rescue.

Although virtually all of the crew were also local Inuits, producer and cinematographer Jonathan Frantz, was a crucial figure. He created epic images of the harsh, snowy landscapes during the chase (see top), often shot in the early morning light of March.

Maliglutit seems to have no distributor. Watch for it in other festivals and eventually on home video–though the scale of the compositions really demands a big, big screen.

From a textbook to an upheaval

If women directors are still struggling to establish themselves in Hollywood, they are much in evidence here at Vancouver. Films from a wide variety of countries were helmed by women, including Mia Hansen-Løve (or Mia Hansen Love as she is billed here), who won the Silver Bear award for best director at the Berlin International Film Festival and the Bucharest International Film Festival. (See here for an interview with the director shortly after the Berlin premiere.)

Her Things to Come (L’avenir) well demonstrates her mastery of traditional, skillful filmmaking. Her camera is locked down rather than restlessly roaming, with simple reframes to follow actors’ movements. The compositions are impeccable, the editing clearly planned in advance, and the story told in an unobtrusive, clear fashion.

I found the film appealing partly because it presents that rare thing, a plausible depiction of the life of an academic. The heroine, Nathalie, played in another star turn by Isabelle Huppert, teaches philosophy in a Parisian high school. Her students are obviously sophisticated kids, and she finds fulfillment in her work. Her husband is an intellectual, and they have two children. Her life seems ideal and her future certain. In the course of the film, however, she suffers a series of setbacks.

Amusingly, these are initially signaled by a meeting with editors at the publishing house that has brought out her textbook and will be publishing a collection of essays aimed at classroom use. The editors cheerfully show her some garish designs intended to boost sales. Her husband announces that he’s leaving her for another woman, her mother needs to be institutionalized, and she loses her job.

The future is suddenly turned upside down, and the film depicts Nathalie’s efforts to maintain her usual cool, in-control demeanor while seeking a new path in life. Although the film is quite sympathetic to her, there is considerable humor as well. Entertaining, thought-provoking, and visually lovely.

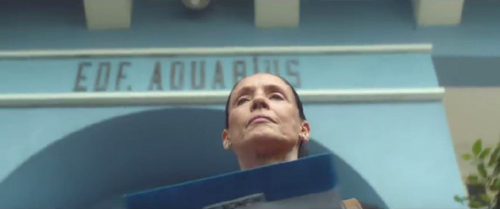

The aging of Aquarius

I was very impressed by Kleber Mendonça Filho’s Neighboring Sounds, shown at the 2012 VIFF. I have been hoping to see another of his films, and this year the festival presented Aquarius. I can’t say that it was quite as exciting as the earlier film, but it is an admirable and entertaining achievement nonetheless.

Again Filho sets his story in his native city of Recife and again the story revolves around predatory real-estate developers building high-rise residences by buying up and bulldozing beautiful old neighborhoods. The earlier film wove together stories of several families living in such a neighborhood, threatened both by criminals and by the encroachment of modern, soulless towers. Aquarius focuses instead on one wealthy dweller in an otherwise empty apartment building, Aquarius.

The one holdout is Clara, a beautiful, wealthy retired music critic in her 60s, who endures various attempts to drive her to sell her apartment. The unscrupulous developers stage a “party” in the empty apartment above her–an orgy and apparent porn shoot. They burn the resulting filthy mattresses in the communal courtyard. They try to catch her in a legal technicality when she has the façade of the building painted, and things only escalate from there.

The film’s effectiveness depends to a considerable extent upon the riveting central performance by Sonia Braga, best known to English-speaking audiences from her lead role in Dona Flore and Her Two Husbands and Kiss of the Spider Woman. A cancer survivor (as demonstrated by Braga when she bares an apparently real mastectomy scar), Clara commands complete sympathy as she fearlessly stands up to her devious persecutors. Despite her wealth, she is friends with her housekeeper and well aware that a short way down the beach across from her apartment, there is a poor neighborhood even more threatened by the developers than hers is.

As in Neighboring Sounds, Filho includes shots of the nearby high-rise blocks looming over the beautiful older buildings. In my earlier entry, linked above, I quoted an interview where the director said, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.” Here the “wrong” architecture is bland, and the older buildings are photogenic.

Aquarius will begin a New York theatrical run on October 21. (Thanks to Erik Luers for the link!)

A poet for, if not of, the people

Another Latin American film shown at the 2012 VIFF that I wrote about favorably was Pablo Larrain’s No. Now he follows up with Neruda. Here we have another film about a poet, in this case the Nobel-prize-winning Chilean author Pablo Neruda. The film follows the dramatic events in 1948 when Neruda’s Communist activities led to a warrant being issued for his arrest. After living in hiding for some months he fled through a mountain pass near Maihue Lake (above) into Argentina and from there to France.

Not surprisingly, many scenes center around Neruda, played powerfully by Luis Gnecco, an actor more typically associated with comedies. (He played the Ricky Gervais/Steve Carrell role in the Chilean version of The Office.) Equally prominent, however, is the police detective who relentlessly pursues Neruda, Óscar Peluchonneau (Gael García Bernal).

Peluchonneau is at once a real detective, a figure fascinated by his quarry, and perhaps a figment of Neruda’s imagination. In a crucial scene, Peluchonnaeau interrogates Neruda’s endless patient and faithful wife (marvelously portrayed by Mercedes Morán; see bottom), and she informs him that he is a mere supporting character invented by her husband. This seems improbable, since Peluchonneau has important causal effects in the narrative, and indeed, his narrating voice continues throughout the film, filtering much of the story information to us. Still, he plays out his supporting role until the end.

I was startled to discover that he and Neruda are parallel protagonists. My Storytelling in the New Hollywood (1999) took Amadeus, Desperately Seeking Susan, and The Hunt for Red October as examples of this fairly rare category. Parallel protagonists largely play out their roles independently, but they are aware of each other and fascinated with each other. One may feel inferior and yearn to be like the other. In Neruda, Peluchonneau is clearly fascinated by Neruda and wishes to be like him. He is, however, far less clever and talented. (Jay Weissberg’s Variety review compares him to Inspector Clouseau.) The ending leaves his status as a character quite ambiguous. It’s nice to know that this unusual option is used in art cinema as well as Hollywood films.

There is a distinct touch of magical realism about Neruda, one that fits in well with the art cinema’s departure from mainstream commercial cinema. It does leave you puzzled in a satisfying way.

Quarrels and cabbage rolls

Don’t ask me what the title Sieranevada means. I have no idea what it has to do with anything that happens in Cristi Puiu’s latest feature. If I had to choose a single favorite from the films I’ve seen so far at the festival, it would be a hard choice between Sieranevada and A Quiet Passion. I have to say, though, that Sieranevada is much funnier, though it took me longer than it should have to figure out that it’s a comedy. Watching the lengthy opening shot, which largely involves the main character’s car being double parked and blocking a DHL truck, I did quickly realize that I was seeing a terrific film.

It is something of a network narrative, based on the familiar situation of a family gathering that exposes long-simmering problems and tensions. (Other examples are Altman’s The Wedding and Vinterberg’s The Celebration.) If we had to pick a central character, it would probably be the medical professional Lary, because we enter and leave the central space when he does, we learn the most about him, and we react much as he does to the amusing twists of action. Still, other family members carry a good deal of the film’s running time, and by the end we observe him with a cooler detachment when his own secrets are revealed.

The main locale is the apartment where Lary’s large family is commemorating his father’s recent death. The apartment has several rooms, all of which are fairly small for the number of people milling about. It’s evidently a set, but one which conveys an entirely convincing sense of seeing an actual cramped apartment.

The party is planned to culminate in a substantial dinner. We see the women of the family cooking, setting the long table, inexplicably taking away the unused dishes and utensils, and assembling plates of food wrapped in plastic (above), to be distributed to the neighbors. Few films have made food look so unappetizing. Mainly, though, these people bicker. The party portion of this 173-minute film occupies about 150 minutes, shot in nearly continuous time.

Puiu handles the whole thing in a virtuoso staging of multiple actions going on in different rooms, with the camera often only glimpsing what one group is doing before a door is closed and the camera moves on to catch another group in a another space. Often the camera pans with one character only to change direction as it catches sight of another, as if it continuously seeks out the most interesting bits of action in this densely populated space. Characters air their obsessions: one cousin is a 9/11 conspiracy believer, and an old lady in a white fur hat upsets the others by touting the accomplishments of the Communist past. We hear grievances too, as when the widow’s sister accuses her husband of carrying on an affair with a neighbor.

Scripting the dialogue for this dense weaves of conversations was a considerable accomplishment. Puiu extracts further comedy by putting so much emphasis on the food and then delaying the actual meal for almost the entire duration of the party. First a priest who must perform a memorial ceremony fails to show up, and then a suit which will feature in another ceremony needs emergency alteration when it turns out to be several sizes too large for the hapless young man who must wear it.

In all, despite its three-hour length, Sieranevada is continually entertaining and an extraordinarily assured piece of filmmaking.

U. S. releases: IFC and Sundance Selects have announced Things to Come for 2 December, while Neruda is scheduled to be released for December 16 from The Orchard.

Aquarius was originally expected to be Brazil’s nomination for the best foreign film Oscar, but political controversy has scotched that. There seems to be no prospect of an American theatrical release. Look for it at other festivals and on streaming. So far, Sieranevada seems not to have secured U. S. distribution, but if it does materialize, seek it out in any way you can. It is Romania’s candidate for this year’s foreign-language Academy Award. It would be a well-deserved miracle if it even made it onto the final list of five.

More recent American examples of parallel-protagonist film are Julie & Julia, discussed here, and Public Enemies and Inglourious Basterds, considered here. The first entry also considers an older example, Enchantment (1948).

Neruda (2016).

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

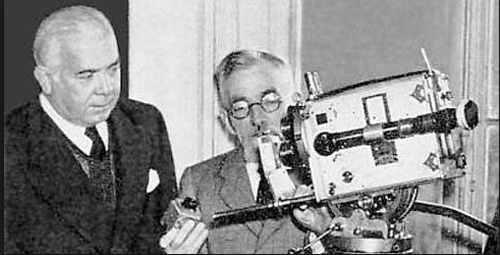

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

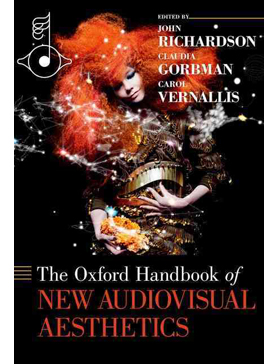

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

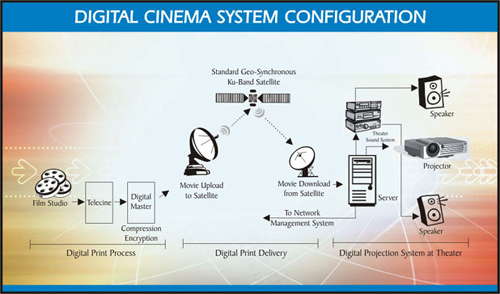

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

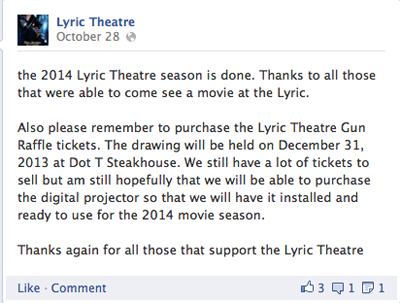

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

VIFF extremes

The Missing Picture (2013).

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival, known to all as VIFF, has been undergoing some big changes. It lost its primary venue, an ageing but cozy multiplex surrounded by pubs, creperies, music clubs, and other marks of downtown culture. Alas, the Empire Granville 7 is now shuttered, to be renovated as a retail space. VIFF must spread its bounty more widely.

As before, films are shown at the Cinematheque and the Vancity media center. The new venues include the Vancouver Playhouse, the Rio Theatre, three screens at the Cineplex Odeon International Village, the Vancouver Centre for the Performing Arts, and the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts at Simon Frazer University. All the ones we’ve visited have been excellent screening spaces.

Everything we’ve seen has been on some form of video—excuse me, “digital cinema.” Apart from the occasional 35mm or HDCam show, DCP projection, after a couple of years of teething pains, is the norm. Not that this guarantees uniformity. Albert Serra’s Story of My Death, a peculiar portrait of the elderly Casanova, still looked (probably intentionally) like it was shot on VHS. The furor about festivals’ conversion to digital formats, discussed in this 2012 blog entry and extended in my little e-book, belongs firmly to history. Henceforth film festivals will be file festivals.

Genres plain and fancy

El Mudo.

As usual at VIFF, the range is wide. At one end of the scale is a feel-good dramedy like The Great Passage, Japan’s Academy Award entry. The central character is Majime, a shy and unworldly young linguist who is drafted to help create a dictionary of Japanese as a living language. An otaku when it comes to words, he soon devotes his life to fulfilling the mission. Over the years he manages to find a girlfriend and earn the respect of the elders steering the project and the friendship of a ne’er-do-well colleague who prefers alcohol to etymologies. The dweeb Majime, despite his sweater-vests and sleeve protectors, becomes moderately sociable, while his pal acknowledges that his own commitment to a geeky endeavor shows he’s not as cool as he thought.

The English title is misleading; a better one might be Crossing the Sea of Language, since the central metaphor is that of charting the ebb and flow of usage. The process is dramatized by setting the start of the project in 1995, before Internet 2.0. The professor overseeing the project points out that the arrival of the Web speeds up language change. The Net works its way into the plot, as card-based research gets replaced by algorithms and word searches. A lot of the film’s humor arises when sequestered scholars, like those in Ball of Fire, have to figure out what this younger generation means when it calls something bad (i.e., good).

Ishii Yuya, who brought to VIFF Sawako Decides (2010) and Mitsuko Delivers (2011), tells his heart-warming story in a trim, efficient manner. His composure could teach our Hollywood directors a thing or two. I didn’t see a wasted shot or gratuitous camera movement, and you might miss Ishii’s virtuoso handling of a crowded office space as volunteers pack in to beat the deadline.

You can often spot a director’s skill in delicate touches. Here, I admired a gentle hook between two scenes. Majime has written a florid, anachronistic letter to Kaguya declaring his fondness for her. At the end of one scene he walks away from the camera clutching the note, which the framing centers on. Cut to a distant shot of him with Kaguya, the letter a small detail alongside his left leg.

Most viewers, I’m convinced, scan to find the letter and then wait with an amused tension for Majime to awkwardly offer it. It’s a good example of gradation of emphasis: No need for a close-up at the start of the second scene. This sort of unforced, easygoing presentation of a plot with a serious point—the quiet heroism of committing yourself to something of value to your community—makes The Great Passage as much worth exporting to North America as Departures and Shall We Dance? have proved in years past.

A more offbeat genre film is El Mudo, a Peruvian quasi-thriller, quasi-comedy from Daniel Vega and Diego Vega. After a day of dreary complaints and insults, the magistrate Constantino finds his car window smashed. What else is new? Soon after, he’s driving through traffic and is apparently wounded by a sniper. He loses his voice but becomes doggedly determined to uncover what he thinks is a conspiracy.

Constantino is not your raging rogue investigator. His muteness only increases a fixed, slightly scowling demeanor that suggests stoicism, boredom, or emotional vacuity. He refuses to perform the exercises that might strengthen his voice, as if he welcomes the loss of one more channel of expression. Everyone else seems normal, but Constantino (played superbly by Fernando Bacilio) might have walked out of an Aki Kaurismaki movie. The filming is in tune with the protagonist–static and prolonged shots, shrewd but unemphatic angles that simply wait for something to happen.

The result is an anti-action film. The assassination attempt, if that’s indeed what it is, is merely a bump in what is otherwise a drab long take filmed from the back seat of Constantino’s car. After waiting for a traffic light to change, he proceeds and suddenly slumps sideways as we hear four faint cracking sounds and watch the car drift onto the curb.

When the case is solved (perhaps) during a police raid, poor Constantino waits outside and so merely glimpses the stunt that would get visceral treatment in another movie. By the end, he finally smiles with pleasure, revealing himself as at a memory of maternal affection; he’s a mama’s boy after all. Il Mudo is a continuous pleasure throughout and is to be recommended to any fan of deadpan grotesque.

Many missing images

We’ve suggested, in both Film Art and elsewhere on this site, that a documentary film can be highly artificial. As long as it purports to make claims about the nonfictional world, the film can stage scenes and even use animation to support its points. A new test of this idea has come along in the form of Rithy Panh’s muted but powerful memoir of Khmer Rouge atrocities, The Missing Picture.

It employs some documentary conventions, like newsreel footage and voice-over commentary, but it seeks to present what was never put on film at the time. Panh’s family is shipped out of Phnom Penh, sent to forced labor and starvation in the countryside. Medical experiments are conducted with humans. Children are forced to pound out fertilizer and haul bodies to burial pits. The Party cadres, of course, eat well. Western intellectuals may have praised the Khmer Rouge as disciplined Communist idealists, but “the revolution they promised exists only on film.” How do you show what was never shown, not even widely known?

To provide a counter-film, Panh fills tabletop tableaus with carved clay figures. By the hundreds, these little effigies populate toy settings of work camps, hospitals that are merely storehouses for the dying, and landscapes that call forth children’s fantasies of escape and memories of happy family life. The figures themselves, squat and chunky, wear emblematic clothes–most often, gray work pajamas–and bear hollow-eyed expressions hinting at sullen fear or merely numbness. Panh’s childhood self is clothed, against all orders, in a pink shirt with yellow dots, which not only lets us identify him but suggests his yearning for the world of color that the Khmer stamped out.

As The Missing Picture proceeds, it becomes more reflexive. The Khmer officials show their propaganda films to the camp audiences, and Panh takes the opportunity to show his figures gathered and obediently watching. At the end, he reminds us that those who resisted are still wandering among us, like ghosts. Some things, he grants, should not be seen or known. “But should any of us see or know them, then he must live to tell of them.”

VIFF may be living in many new houses, but it’s definitely living, and as splendidly as ever.

The Empire Granville 7 was the last remaining movie house on Vancouver’s Theatre Row, which at one time had over twenty theatres. On the Granville 7’s future as retail space, a story is here. This article mentions that the Granville 7 originally absorbed a theatre called the Coronet. Cinema Treasures supplies more details of Granville 7 history. Images of the interior demolition of the house are here.

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).