Archive for the 'National cinemas: South America' Category

More of the world in a multiplex: another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Latin America

In my first report, I mentioned that the Iranian film A Respectable Family was an unexpected gem. I’ve come across another, the Brazilian film, Neighboring Sounds (2012). It has a remarkable formal device that unfortunately I can’t disclose without ruining the film for those who haven’t seen it. It’s a technique that takes a while to figure out, since it’s cumulative. (Fortunately, unlike with A Respectable Family, I have yet to find a review or program note that mentions it.)

The film is set in Recife, the fifth largest city in Brazil. It centers around members of two families living in a complex of smaller, older houses surrounded by new condo high-rises that will eventually swallow the entire area. (The image above vividly shows the juxtaposition.) The divide between rich and poor is extreme, however, and the residents live in fear of crime, with elaborate gates and with grilles over their windows. Suspense is generated when a small group of men offer their services to provide security for the block, and once they are hired, we are left for a long time to wonder whether this is a cover for some other devious purpose.

The film is beautifully shot, taking advantage of the abstract compositions created by the modern apartment blocks and their glass windows and doors. As director Kleber Mendonça Filho says in the online press kit, “Architecture gone wrong is a nuisance, but extremely photogenic.”

The film’s title is taken literally, with many layers of offscreen sounds from nearby houses and streets forming much of the soundtrack. The complex use of Dolby Surround makes it especially desirable to view and listen to this film in a theater.

Neighboring Sounds has been picked up for US distribution by the Cinema Guild, which has handled other films we’ve enjoyed here in Vancouver , most notably Once upon a Time in Anatolia and The Strange Case of Angelica (and written about here and here, both available on DVD and Blu-ray.)

The Chilean film No (2012), starring Gael Garcia Bernal, has already gained a high reputation on the festival scene. (Like A Respectable Family, it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.) David and I both thought it lived up to its buzz.

The plot deals with the 1988 referendum as to whether dictator Augusto Pinochet would remain in power. The side campaigning for the “no” vote was allowed a single 15-minute TV commercial each evening. Bernal plays a successful director of TV ads, Rene, who is lured into devising this commerical; he’s introduced showing off his latest spot for “Free” cola. He conceives of a campaign based on breezy optimism, with musical numbers (below right) and shots of cheerful workers acting as if Pinochet is already out of office. His tactics disgust several of the left-wing party leaders, as well as Rene’s estranged wife.

Technically the film is cleverly done. It was shot on old-fashioned U-matic video and shown in Academy ratio (not exactly reflected in these frames from the online trailer). Fuzzy images with occasional overexposure and other video artifacts not only suggest a period piece, but they also allow director Pablo Larraín (Tony Manero, Post Mortem) to seamlessly edit in historical footage of Pinochet and street clashes from 1988. No generates considerable suspense as well, whether or not one knows how the referendum turned out.

Sony Pictures Classics picked up No at Cannes and currently lists its release date as to be announced; according to IMDB, it will have a limited release in the USA on February 15.

Europe

A Royal Affair (2012, Nikolaj Arcel) has been chosen as Denmark’s entry for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar. Of course, the long list of entries from various countries will be reduced to five before the voting occurs. Still, I wouldn’t be surprised if A Royal Affair ended up on the final list and even took the top award. In a way, it’s just what the Academy members like: a big, glossy costume drama based on uplifting historical events.

But I was relieved to discover that this is no Merchant-and-Ivory-style middle-brow adaptation. It’s a fascinating example of what happens when a bunch of leftist, cutting-edge filmmakers get their hands on a budget to make an historical epic. Although the film’s title and publicity center on the illicit romance that provides part of the drama, A Royal Affair focuses largely on politics. Its plot is loosely based on historical events during the Age of Enlightenment, during which Denmark initially remained a backward country based on serfdom, summary arrest, torture, and execution, and grinding poverty for the lower classes.

The opening shows the heroine, Caroline, born an English princess and wed to Danish King Christian VII, writing the story of her life for her children. A flashback then begins the story proper, with Caroline optimistically setting out for Denmark and quickly discovering that her husband is an impetuous, rude and possibly insane young man who cares nothing for her. Her loneliness and the backward situation in Denmark are gradually established. Eventually a young doctor, Struensee, who believes in the ideas of the Enlightenment philosophers, comes to court and befriends the king, helping him to behave in a more restrained fashion.

Caroline, too, is a devotee of Rousseau, Voltaire, and other authors whose works are banned in Denmark. Nearly an hour  into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

into the film, she discovers that Struensee is of like mind, and a friendship gradually moves into love and a sexual affair. The couple manipulate Christian into passing laws to benefit the peasants, earning the ire of the nobility. The narrative continues to center more on the social struggle that the three carry out than it does on the romance plotline.

When I heard that the Silver Bear for Best Actor was awarded to the film at Berlin, I assumed it went to Mads Mikkelsen, who plays Struensee–and seems to star in half the films coming out of Denmark these days (such as Thomas Vinterberg’s The Hunt, also shown this year in the festival). But the role of Christian VII actually seemed to me more challenging. Mikkel Boe Følsgaard has to play a character who begins as border-line insane, crude, and obnoxious, but who also must gain our sympathy when he becomes part of the plot to reform Denmark’s laws. I was delighted to learn upon further inquiry that is was in fact Følsgaard (on the left, with Mikkelsen, in the photo) who won the award. Well deserved.

As the image suggests, the film is shot in muted tones that tend to play down the costumes and sets more than historical dramas usually do. This approach helps direct our attention to the plot and politics rather than the pageantry. In short, I ended up liking the film much more than I expected to.

A Royal Affair will be released in the USA on November 9 by Magnolia Pictures.

At the other end of the budgetary scale is the Portuguese feature The Last Time I Saw Macao (2012, co-directed by João Pedro Rodrigues and João Rui Guerra da Mata). A common impulse among critics seems to be to compare this mysterious, lyrical film to some of Chris Marker’s works. There is little information available on it, but my impression was that the filmmakers shot a lot of lyrical footage of Macau and then concocted a story to fit it. There are shots of buildings, from skyscrapers to disreputable-looking back streets, as well as ephemeral items like some big, gaudy, cartoony balloons of tigers that decorated the streets for a local festival.

The plot has something to do with a mysterious gang, the Chinese zodiac (see image at the bottom), and the end of the world. The hero is barely glimpsed, narrating the story in voiceover (provided by both of the directors). The plot centers on his search for a transvestite named Candy, perhaps the “woman” seen performing a musical number in front of a cage containing live tigers in the sultry opening scene. The song, “You Kill Me,” is among several references to Josef von Sternberg’s Macao.

Despite the shoestring budget, the filmmakers manage convincingly to portray an apocalyptic destruction of the city, followed by bleak shots of deserted, early-morning Macao buildings that effectively suggest the aftermath. It reminded me of Godard’s depiction of a futuristic city in Alphaville, using contemporary buildings and highways.

No US release is planned, but The Last Time I Saw Macao is worth seeking out at upcoming festivals.

A Filmmaker of the World

I’ve mentioned some films that pleasantly surprised me, but almost certainly the best film we saw at Vancouver came as no surprise at all. We both loved Abbas Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love, but we’re not going to write anything substantive about it, at least not now. It deserves another viewing or two before we could say anything worthwhile–and it hardly needs us to publicize it. The opening scene is fabulous, the subsequent rambling plot absorbing and intriguing, and the end, as so often happens with Kiarostami, puzzling and frustrating. Possibly the man can do no wrong.

IFC has theatrical rights for the USA. Currently its webpage announces “Coming in 2013.” This may mean primarily On Demand, though it would be a pity not to see Like Someone in Love on the big screen.

The end of one multiplex

Rumors circulated almost from the start of the festival, and on October 8 the festival’s director, Alan Franey, revealed officially that the Empire Granville will soon be closing down. A detailed story on the history of the Granville and its closing, with quotations from Franey and representatives of other film festivals that have used the venue, can be found here. Ideally next year’s festival will house most of its screenings in another of the city’s multiplexes, but the new venue is yet to be determined. We hope it will be someplace where we can bounce around the world from screen to screen as easily. The Granville has served us all well and will be missed.

More riches from Bologna

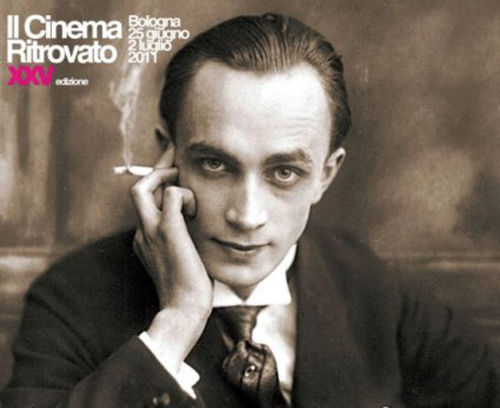

We’re still catching up with last week’s generous Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, the world’s premiere festival of restored and rediscovered films from all eras.

DB here:

O Segredo do corcunda (The Hunchback’s Secret, 1924) was more than a curiosity. Directed by the Italian Alberto Traversa, it was the first Brazilian feature screened abroad. It also has a documentary bent in that it shows a bit of what coffee farming was like in that era. The plot traces how the budding romance between a poor boy and the plantation owner’s daughter is blocked by the overseer Pedro, who actually killed the boy’s father.

The film illustrates penetration of Hollywood filming technique around the world. The linear plot includes a flashback explaining key motivation, a romantic subplot with helper characters, and a last-minute rescue built out of parallel editing. Scenes are filmed and cut according to continuity principles, with eyeline matches and angled changes of setup. There is even a split-screen delirium sequence.

Yet the film was out of step with Hollywood in one respect: the proportion of titles, especially dialogue titles. O Segredo do Corcunda has a lot of intertitles; they make up 22% of all its 518 or so shots. Somewhat similar proportions can be found in the mid-1920s in Hollywood, as Upstream and Cradle Snatchers indicate. But what’s different is the proportion of dialogue titles to expository ones. Most Hollywood films of the period have a very small proportion of expository titles, usually no more than 15% of all titles, and often much less. Fazil, discussed in an earlier entry, has 118 dialogue titles and only seven expository ones. But in O Segredo the 65 dialogue titles comprise 57% of all titles, leaving the 49 dialogue titles to make up the difference.

Why does this matter? In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I argued that American generally tend to favor methods that let the story seem to tell itself. Although an early silent feature might have many expository titles, in the late 1910s and the early 1920s, films began minimizing expository titles and letting dialogue carry the action. By the 1920s a US film would have relatively few expository titles. The pattern is visible across a film as well, with expository titles most common in the opening scenes but diminishing as the plot proceeds. In Segredo, not only do expository titles do more work, they’re spread out pretty evenly across the film. An external narrational authority is there from start to finish.

I suspect that the method of fading external authority is an identifying mark of American silent film and is rarer in other cinematic traditions. If that hunch is right, we can ask: Why did other countries persist in using expository titles so much? Matters for further research!

Polustanok (A Small Station).

Boris Barnet started out as one of Lev Kuleshov’s circle, and he became a well-established director. Not as famous as the Big Three (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko) or even Kuleshov, Barnet directed charming comedies like The Girl with the Hat Box (1927) and The House on Trubnoi Square (1928) and heartfelt dramas warmed by music, such as By the Bluest of Seas (1935). But many of his later films are unknown to me. I couldn’t catch all the titles in the Barnet retrospective, but the two features and one short I saw convinced me of his gifts.

Those gifts come off as gentle and genial in the wartime feature A Good Lad (Slavny Maly, 1942). A French pilot’s plane is downed in a Russian forest, where a resistance group is hiding out and forming its own little community. Living under the imminent threat of discovery doesn’t forestall songs, romantic affairs, and mistakes born of the language gap. (“I love you.” “I don’t understand.” “I don’t understand.”) Somber notes are struck when the village poet strides along singing patriotic tunes set to Borodin’s melodies, and soon the German soldiers are finding some partisans to threaten. With the villagers’ help the plane is repaired and soars into the sky to engage the enemy. The film seems to take place in an otherworldly realm, floating between an idyll and a battlefront drama.

Twenty years later Barnet could indulge in a more relaxed pastoral. Polustanok (1963) is variously known as Whistle Stop or A Small Station. A Moscow scientist goes on a painting vacation to the countryside. He settles into a collective farm where many painters have come before and winds up in a shed that is underfurnished (the chickens have to be shooed out) and overdecorated (the walls are covered with graphic inspirations). With something of the episodic structure of M. Hulot’s Holiday (though without its rigorous underlying timetable, at least to my eye), A Small Station rings variations on the fish-out-of-water situation of Pavel Pavlovich. He makes friends with a local delinquent, the party man, and cute girls. He even gets some support from the grumpy farm lady who has been painted many times and in many styles, some surprisingly unofficial in those Krushchev years. After Pavel sets painting aside, he and the delinquent build a brick stove for his shed. He signs it as if it were a work of art. He can return to Moscow reinvigorated, and as so often happens in films like this (Local Hero comes to mind), the departure is bittersweet.

Barnet’s light touch was nowhere in evidence in the long-unavailable short Priceless Head (A Bestsenaya golova, 1942). On every corner of an occupied Polish city, the Nazis have mounted a reward poster for a wanted partisan. He realizes he’s trapped, and meeting a penniless woman unable to feed her sick child, he offers to let her turn him in. This impossible choice is rendered in precisely controlled drama, with not a wasted shot or false note. Priceless Head shows that Barnet was an outstanding dramatic director, as well as Soviet cinema’s most unassuming lyricist.

Underground New York.

What would a trip to Bologna be without a foray into the 1910s? Kristin will have a lot to say about the biggest discovery, the consistent excellence of Alberto Capellani, so I’ll contribute a mite on the things I enjoyed. Of course I tracked the Feuillades. Roman Orgy (1911) was fairly tame, even allowing for a climax of Christians crunched by lions in the arena. Bébé est neurasthénique (1911) was shamelessly silly, with the little rascal pulling dishes off the table and then escaping punishment by feigning illness. His gift for rolling his eyes back into his head proved to be as funny on the tenth instance as on the first. But the most peculiar Feuillade entry was a sort of satiric PR response to Les Vampires. Lagourdette Gentleman Cambrioleur (1916) shows Musidora, no longer Irma Vep, absorbed in reading the novelization of Les Vampires. Marcel Levesque decides to woo her by pretending to be a debonair thief, so he convinces his valet and cook to pose as wealthy opera patrons. He’ll then display his skills by robbing them in front of Musidora. The two-reeler accepts, in a mocking spirit, the charge from bluenoses that sensational stuff on the screen only encourages crime.

Lagourdette has its nice points, notably its tendency to supply very large close-ups of its principals. (Who knew that Musidora had freckles?) This technique, almost absent from Feuillade’s features of the period, may have been an adaptation to the star-driven nature of the product. As Annette Förster noted in her introduction, the film involved a sort of product placement, and Gaumont’s stars, no less than its literary spinoffs, were branded items. The movie is minor Feuillade but significant in showing that as early as 1916, filmmakers were seeking synergy.

Mauritz Stiller began directing in 1912, and through 1914 he turned out some 20 films. All have been assumed lost, but one surfaced in Poland a few years ago. It was restored in 2011 by the Swedish Film Institute, so once more Ritrovato hosted a “second world premiere.” Gränsfolken (People of the Border aka The Border Feud, 1913) is derived from a Zola novel. A boy and a girl fall in love, but their families live on opposite sides of a border. For the girl’s father, loyalty to country comes before all else, and so he tries to block the marriage. Nonetheless the couple unite, but they face a dilemma when the two countries plunge into war. Will the young man fight for his old homeland or his new one? And will his ferocious brother kill him as a traitor?

Stiller had mastered the tableau style of the 1910s. Although nothing in the film displays Victor Sjöström’s virtuosity in staging, Stiller gets a lot of mileage out of the two families’ densely furnished parlors. Every inch of the frame is used at some time or another; a figure lying on a tall bed can roll into view in the upper left corner of the shot. The exteriors are picturesque and often framed geometrically. I need to see Gränsfolken again to do justice to its visuals, but the fairly restrained playing and the emotional intensity of the situation prefigure what would become signature elements in Stiller’s style in work like the Thomas Graal comedies and of course Herr Arne’s Treasure (1919).

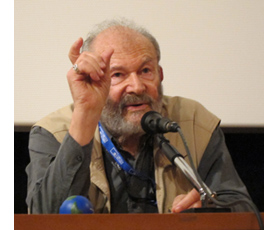

Jumping far ahead to the 1960s, it was a pleasure to see Gideon Bachmann’s Underground New York. Shot in 1967, it treats protests against the Vietnam War as of a piece with the avant-garde film scene. Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas, the Kuchars, Bruce Conner, and other legendary figures are captured in quick, telling portraits. Andy Warhol confides that acting in his film involves not performance but “faking it.” There are many lively moments—Conner dancing in pegged pants, Mekas tearing up company checkbooks—and enough nudity to suggest that new filmmaking and political protest were tied to erotic liberation.

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Over eight hundred hours of those meetings have been preserved in Bachmann’s audio archive, Vox Humana—The Voice Bank. The model for Bachmann has always been not the interview, with its predictable questions and stale answers, but the conversation, “just friends talking.” Bachmann, a straightforward and serious man, was forty when he made Underground New York, and he retains the mature lucidity on display in his comments in that film—and in his film criticism, which I remember reading with pleasure in Film Quarterly in the 1960s. We’re likely to get an earful of his archive, for Criterion has already signed up the North American rights to the Vox Humana collection.

KT here:

Given the great abundance of films at this year’s festival—some might say an overabundance—I singled out out three threads to concentrate on. I resolutely ignored the others unless I could somehow fit a film in here and there. Naturally I chose the second part of the Albert Capellani retrospective that began last year; I wrote about the 2010 season here and will do a follow-up soon. I also chose the 1911 “Cento Anni Fa” programs, since, as usual, the festival presented films from exactly one hundred years ago. Not surprisingly, the most interesting among these were by Feuillade, which David covers above, and Capellani. Finally, since I have a particular interest in Weimar cinema, I stuck with the “Conrad Veidt, From Caligari to Casablanca” retrospective.

The title refers to what are probably Veidt’s two most famous roles, as the somnambulist Cesare in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) and his final performance, as the Nazi Major Strasser, in Casablanca (1942). But presumably on the assumption that just about everyone knows these two films well, Il Cinema Ritrovato didn’t show either one. Instead, the program successfully assembled a group of lesser-known Veidt performances. Despite the fact that I’ve seen a lot of Veidt’s films from the 1910s and 1920s, almost all the items on offer were new to me. The selection seemed designed to display the considerable range of an actor often identified with villainous roles, like his portrayals of Nazis in the 1940s, or downright demonic, like Ivan the Terrible in Waxworks.

Almost none of the films in the program were newly discovered or restored. Most were drawn from existing prints held by various archives. The Wandering Jew, for example, was a beautiful print from the National Film and Television Archive, but it was full of splices, often with whole lines of dialogue missing. The exception was The Thief of Bagdad, a newly restored version shown as one of the evening screenings in the Piazza Maggiore. Not having the stamina that we once had for nearly round-the-clock film viewing, David and I missed all of those. I also passed up the familiar Waxworks (1924, Paul Leni), which I gather was shown in the same dark, indistinct version that has been circulating for years. It’s a film ripe for restoration, but perhaps no better material survives. That would be a pity, since it’s the one film that three of the main Expressionist actors, Veidt, Werner Krauss, and Emil Jannings appeared in together. Leni is also an interesting director, as well as a set designer; perhaps a retrospective of his largely unknown body of work could be arranged someday.

Apart from these, the program pulled together an admirable selection of films. The earliest, Dida Ibsens Geschichte (“Dida Ibsen’s Story,” 1918, Richard Oswald), was a sequel to the original version of Das Tagebuch einer Verlornenen, later remade in 1929 by G. W. Pabst with Louise Brooks. Veidt features relatively little in Dida Ibsen, playing a rich man who takes Dida as his mistress. The film is stolen by Werner Krauss, however, playing a highly eccentric man who forces Dida to marry him and then terrorizes her and their little daughter. Their home is crammed with what appear to be the exotic souvenirs of the husband’s adventures, including Asian furnishings and curios, as well as a parrot, crocodile, and lively python. Krauss carried the latter curled around his body much of the time. Indeed, where else could one see two snake-carrying villains in a single week? Three days later I watched Burl Ives sporting a cottonmouth moccasin in Nicholas Ray’s Wind across the Everglades, a film from the color series that I managed to fit into my schedule.

Veidt’s demonic roles are well represented here not only by Waxworks but also by the 1922 historical epic Lucrezia Borgia (also directed by the prolific Richard Oswald). I had expected the latter to be the usual stodgy historical drama, but it was livelier and more enjoyable than I had expected. Veidt plays the ruthless Cesare Borzia, lusting after his sister Lucrezia and scheming against her repeatedly until he leads a suicidal attack on the fort where her husband is defending her. The fort itself is an immense, lumpy set of the kind common in German epics of the 1920s, That, along with the huge armies of extras, suggests that this was one of the biggest-budget films prior to Metropolis.

Veidt was more versatile than such roles would suggest, however. He often played intense, suffering young men, as in one of F. W. Murnau’s earliest surviving films, Die Gang in der Nacht (1920, not, as in the catalogue, 1922). Veidt plays a supporting role as a mysterious, spiritual young painter who has been blinded. His more cheerful side was in evidence in the wonderful musical The Congress Dances (19331, Eric Charell); there as the confidently scheming Metternich he smilingly relishes eavesdropping on officials and politicians and reading their sealed letters with a contraption involving a bright lamp and magnifying lenses. He plays a Prussian military hero in Die letzte Kompagnie (1930, Kurt—later Curtis—Bernhardt), an early talkie shown in what appeared to be an English-language version, part dubbed, part redone with the actors speaking English.

Veidt’s ability to play both sympathetic and dastardly characters was shown off in the final two offerings, scheduled back to back, in both of which he plays diametrically opposed brothers: Die Brüder Schellenberg (1926, Karl Grune) and Nazi Agent (1942, Jules Dassin). Seeing the two films juxtaposed was odd. In each one, the evil brother is played by Veidt as he usually looked, with dark hair slicked back from his face, while the virtuous brother is gray-haired, reserved, with a little goatee (below). One has to suspect that Dassin saw the earlier film, and in fact Die Brüder Schellenberg was screened at the festival in an American print entitled Two Brothers.

The Mosfilm site offers some Barnet titles for downloading, without subtitles and for a fee. The short list includes A Small Station. The opening twelve minutes, with subtitles, can be found on YouTube. A Good Lad is available here, for free, without subtitles.

For a lovingly compiled fan site, see The Conrad Veidt Society, but beware the Wikipedia entry.

[Thanks to Armin Jäger for correcting my mistake on the date for The Congress Dances.]

Conrad Veidt and Conrad Veidt in Nazi Agent.

ROW, take a bow

Of Love and Other Demons.

Kristin here:

There are dozens of American films playing at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, but the vast majority of them are documentaries. Once again the Rest of the World (ROW) gets its turn. David has started by handling a group of Asian films (one of the festival’s specialities), and I’ve got films from three continents to describe.

Morgen (Romania; dir. Marian Crisan, 2010)

Morgen opens with the camera following the hero, Nelu, riding his motorcycle toward a border checkpoint. The border guards question him and discover that he’s been fishing and caught a large carp. One guard is inclined to let him pass, but the stricter one insists that he can’t take it across. We may think that this guard wants the fish for himself, but when Nelu finally empties his bucket into the gutter, the guards retire into their office and the fish is left to flap pathetically as Nelu rides across the border.

It’s a simple, obvious way to set up the absurdity and arbitrariness of border controls within the European Union, but it also sets up the character of the two guards, who will figure later when a more important border-crossing is attempted.

A security guard at a local grocery store, Nelu lives with her termagant wife in a modest farmhouse near the Hungarian border. During one of his regular fishing trips, he spots a forlorn Turkish refugee hiding from the border police. He takes the man home. Although the Turk’s dialogue isn’t subtitled, he mentions Germany often enough for Nelu and us to grasp where the man is heading. Not having a clue about how to help, Nelu hides the Turk in his cellar, and despite the wife’s objections, he gradually becomes a sort of handyman around the place. Nelu keeps telling him, “Morgen” (“tomorrow”) suggesting that he vaguely hopes to do something eventually.

Virtually every scene occupies a single take, some long, some not. But these aren’t the deliberately lugubrious shots of a Béla Tarr. In its quiet way, Morgen is a comedy, and an entertaining one. Nelu’s passivity presents the slowly growing friendship between him and the Turk without the film tipping over into sentimentality, and there is genuine suspense in the scenes of threatened encounters with the border police and guards. It’s a charming film, reminiscent of some of the Czech New Wave comedies of the 1960s.

12 Angry Lebanese: The Documentary (Lebanon; dir. Zeina Daccache, 2009)

The film’s subtitle is intended to differentiate it from a play of the same name that was produced within the largest prison in Lebanon, starring a group of prisoners. In the United States the director, Leina Daccache, studied drama as a method of prisoner habilitation. She managed to get funding to try the first ever use of this method in Lebanon, though there followed a year of negotiations before government officials allowed the experiment. The  program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

program was to include a loose adaptation of the American play 12 Angry Men, as well as some songs and monologues by the prisoners. Eight soldout performances were eventually put on, attended by government ministers and members of society.

The process of casting and rehearsals took fifteen months, and Dacchache documented the process with a cinematographer shooting digital video. There are atmospheric shots of the prison, scenes of the rehearsal and premiere performances, and interviews with the prisoners who play the lead roles. The resulting images are necessarily not of high photographic quality, but the intrinsic drama of the situation more than makes up for that.

Although 45 prisoners were involved in the performances, Daccache wisely concentrates on the central dozen, composed of several murderers, some drug dealers, and a rapist. Even in the early interviews, before rehearsals have progressed very far, all are remarkably articulate and thoughtful about their own lives and how they ended up in prison. (Presumably they were chosen because they could speak so revealingly.) By the end, they realize that they have learned all the things they were deprived of during their early years, most notably how to function as a group and work toward a goal beyond their own wants.

The film creates a moving and convincing image of the effects art can have in changing the lives of prisoners thought to be beyond rehabilitation. It’s a rare documentary that has an immediate positive effect on society. In this case, there had been a law providing for early release for prisoners on the books in Lebanon for several years. As Daccache revealed in a Q&A after the film, that law was never put into practice until after the successful run of the play.

Of Love and Other Demons (Costa Rica/Colombia; dir. Hilda Hidalgo, 2010)

Filmmaking on a sophisticated level continues to spread through Latin America. Hidalgo’s adaptation of Gabriel García Márquez’s novella seems to have been shot in Costa Rica, with financing and other technical work done in Colombia.

The story is relatively simple. The teenage daughter of a local nobleman in colonial Cartagena is bitten by a rabid dog. It’s not clear whether she has contracted the disease, but she is taken to a local nunnery and locked away in a cell for observation. Somehow the diagnosis is changed to demonic possession, mainly because the girl has been raised by her family’s black slaves and has been steeped in their native, highly non-Catholic beliefs. A young, philosophically minded priest is sent to exorcize her but ends up falling in love with her instead.

In contrast to the slapdash editing so common in contemporary Hollywood films, it’s a pleasure to see a film where every shot has been intelligently planned. The Variety review compares cinematographer Marcelo Camorino’s lighting to Caravaggio paintings, an apt parallel. The heroine’s implausibly dense, waist-length red curls are lovingly dwelt upon, as in the shot illustrated at the top of this entry. The sense of magical realism emerges most powerfully in a dazzling sequence in which the priests watch a solar eclipse. A moon far larger than it would normally appear passes across an equally huge sun, creating a fiery corona that hovers above the open sea (see below).

Microphone (Egypt; dir. Ahmad Abdalla, 2010)

Ahmad Abdalla, whose first feature Heliopolis we blogged about last year, is back with his second. Microphone is much more polished, reflecting a longer shooting time and perhaps a bigger budget. The same lead actor, Khaled Abol Naga, returns as Khaled, a young man returning to his native Alexandria after seven years in the United States. Finding that the girl he had hoped to marry has decided to go abroad to do her Ph.D., he sets out to help set up a studio in a warehouse. Gradually he gets drawn into the more popular goings-on in the working-class districts, notably rap music, skateboarding, and graffiti art. After a hypocritical government arts bureaucrat promises funding and then reneges, Khaled sets out to stage a concert in the open air, only to be confronted by Islamic and police opposition.

While Heliopolis simply followed a set of disparate characters around the upscale Cairo suburb, Microphone has a more ambitious structure, flashing back to stages in Khaled’s disillusioning reunion with his ex-girlfriend–flashbacks that are presented out of order within the ongoing scenes of his growing interest in street art. The result has the sophistication of a modern festival film.

The film presents a grim take on government repression and censorship. Abdalla, on hand to answer questions, told us that we had seen the full version, which he fully expects will be cut by the Egyptian authorities. Even  though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

though he shows the young street artists in a sympathetic light throughout, Abdalla does not avoid the fact that their work is wholly positive. There is a motif of Khaled opening his shutters each morning to a view of an aging yellow stucco building across the way; one morning he opens again to find the façade covered with a giant graffiti image.

Indeed, one audience member, a young man from Alexandria, objected to the portrayal of his beautiful home city as ugly, since the story is set mostly in poorer neighborhoods. Abdalla defended the approach, saying that the film is intended to portray a certain arena of life in the city realistically, with the incidents in the film being derived from stories recounted to him by the actual young artists who played themselves.

The film’s criticism of the Egyptian government may seem rather tame by western standards. Yet a telling change in the ending reveals how current are its concerns. There is a street vendor selling pop-music cassettes out of a cardboard box who returns at intervals as a motif, though he has little to do with the story. The film was to have had an upbeat ending involving the vendor. But in June, when the filming was still going on, the beating death of Khaled Said by two policemen outside an internet cafe in Alexandria took place. The filmmakers altered their ending, with police chasing the cassette vendor and starting to beat him. (The trial of the real-life policemen is ongoing and has every appearance of being a sham.)

The Man Who Will Come (Italy; dir. Giorgio Diritti, 2009)

This film dramatizes a set of massacres of villagers perpetrated by Nazi soldiers in the region around Bologna in 1944 in response to the people’s support of partisan troops. It’s a tale told through the eyes of Martina, a girl of about 9 who has been mute since her newborn brother died in her arms. (No points for guessing whether she regains speech by the end.) Since the main peasant family to which Martina belongs is fictional, there was no necessity to make her mute, and unfortunately the result is that she has very little personality. She is shown being bullied by some boys early on, which presumably is intended to make us sympathize more with her, though the choice of a pretty little girl as the point-of-view figure entails a pretty automatic sympathy on the audience’s part.

The film is largely episodic, with the life of the central peasant family and their neighbors being vividly conveyed as we see them at their tasks. At intervals, Nazis are seen near the village, and the partisans recruit young men and have some early successes. But since Martina understands little of what goes on around her, she has no particular goal, though eventually she gains one as the Germans begin the massacre and she is left to save another newborn brother. I found it difficult to keep track of the lengthy scene of the rounding up of the peasants and their executions in various venues. One group is taken to a chapel in a graveyard to be killed, another is killed by the church, and so on, but it is difficult to tell one group from another or to get a sense of how many peasants were slaughtered. (The original total was somewhere around 750 to 800.)

Overall the cinematography conveys the setting well, both the hilly, wooded landscapes and the ancient stone farmhouses. There’s a very effective scene where the townspeople take refuge in a church and Martina’s older sister runs back and forth from the bell-tower, reporting the fighting below, which we see only from far away, as she does. In fact, this sister is a more engaging character than Martina, and would have made a better point-of-view figure. Another gripping scene comes when she, seriously wounded in the massacre, is suddenly pulled out of the pile of bodies and given first aid by a Nazi officer. She’s mystified as to why he’s doing this, though we hear him tell another soldier that she reminds him of his wife. It may seem as if the insanity of war would be more effectively conveyed through a thoroughly naive character’s eyes, but at least in this case, somehow that doesn’t work.

Of Love and Other Demons.

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.

Exasperating and exhilarating, Film Socialisme shows no flagging of its maker’s vision. “He’s a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher,” a friend remarked. Or perhaps he’s a filmmaker who thinks he’s a painter and composer. In any case, Film Socialisme will be remembered long after most films of 2010 have been forgotten. More intransigent than most of his other late features, and unlikely to be distributed theatrically outside France, if there, it shows why we need “little” festivals like Cinédécouvertes now more than ever.

The home page of the Cinematek is here. A complete list of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes winners is here. Last year, between research and preparing for Summer Movie Camp, I had no time to blog about the festival. But you can go to my earlier coverage for 2007 and 2008.

As one who cares about Godard’s aspect ratios, it pains me to use illustrations from online sources, which are notably wider than the version I saw projected in Brussels. When I can get my hands on a proper DVD version, I will replace these images with ones of the right proportions.

Seeing movie seeing: Display monitors in the reception area of the Cinematek.