Archive for the 'National cinemas: South America' Category

The ROW strikes again

The Time that Remains.

Kristin here:

Last year I remarked on how festivals like Vancouver are increasingly showing films from countries that have barely contributed to world cinema until recently. Not surprisingly, the trend continues. Yesterday I saw The Search (dir. Pema Tseden), the second feature to by made in Tibet by a team of Tibetans. (The first was also by Tseden.) It’s strongly reminiscent of Kiarostami’s best-known films, with a small film team traveling through the countryside trying to cast a movie based on a classic indigenous opera.

So far, however, most of the films I’ve seen have been from more established filmmaking regions.

Latin America

Latin American cinema continues to grow beyond Mexico, Brazil, and Peru, largely thanks to European co-productions and occasionally co-productions between countries within the region. For me, the first day of the festival concentrated on Latin America.

The first stop was Peru, with the surprise winner of this year’s Golden Bear at Berlin, Claudia Llosa’s The Milk of Sorrow. The plot concerns Fausta, a young woman whose mother, pregnant with her, was raped and tortured during era of the government’s war against the Shining Path insurgents (1980s-1990s).

Haunted by a fear of being raped herself, Fausta imitates a trick that a woman supposedly employed to fend off attackers. She places a potato in her vagina, hoping that the protruding shoots will repel a would-be rapist. Her terror of leaving home alone limits her freedom, though she manages to take a job as a maid to an eccentric female pianist. Her plight is ironically emphasized by the fact that her uncle is a wedding coordinator, and there are several scenes involving outgoing young women who are attuned to modern life and eager to marry.

The Milk of Sorrow is beautifully shot, with a minimal plot that proceeds at a languorous pace. It fits very much into the art cinema destined primarily for festival and big-city screenings.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Two other two films of the day were distinctly more reminiscent of Hollywood in their pacing and strong plots. Sebastián Silva’s The Maid has a familiar plot, the repressed character who needs to learn to enjoy life and other people. Raquel has served the same family for decades and become obsessed about her own little domain of power, pampering one child she adores, annoying another, and running the household to suit herself. Eventually, when an outgoing second maid is hired, Raquel is surprised to find herself with a friend and begins to come out of her shell.

Stylistically there’s nothing of great interest. As with so many films these days, it was shot in real locales, mostly the interior of one large house, and so consists mostly of medium shots and lots of panning. It’s essentially an actor’s film, though, and I could easily imagine it being remade in English as a vehicle for someone like Meryl Streep. It effortlessly balances drama and humor and is continually entertaining. It also features the only unequivocally upbeat ending among the films I’m discussing here, which no doubt says something either about the state of the world or about what filmmakers assume festival programmers look for.

Equally skillful but miles away in tone is the Mexican feature Backyard, by Carlos Carrera. Focusing on the astonishingly frequent rape, torture, and murder of women in Juàrez, the film follows a lone female detective in a police force which refuses to arrest or prosecute any of the perpetrators. (Above, she is confronted with hundreds of photos of the dead and missing.) The reasons behind both the numerous murders and official indifference turns out to be a combination of circumstances: at least one serial killer with the means to pay off the police, the executive of a Japanese factory that doesn’t want bad publicity, and random abusive husbands and young punks who take advantage of the situation to dump their victims in the desert with impunity.

The story is handled in taut classical fashion, intercutting between the detective’s investigations and the story of one young factory girl factory who eventually becomes a victim. This is the stuff of CSI and other crime shows, but all based on a horrific real-life situation that goes beyond what any mainstream drama would dare to show and that continues to this day right, as the title emphasizes, in America’s backyard.

One of the best films we’ve seen so far is Lucrecia Martel’s third feature, The Headless Woman. Although I had admired her visually gorgeous La ciénaga (2001), I found it a bit obvious in its use of the central swamp metaphor to characterize the upper-middle class. The Headless Woman, though, is the epitome of subtlety, with the plot being a puzzle with easily missed clues doled out sparingly. (The Variety review considerably mis-describes what happens, and I suspect others do as well.)

The opening is simple enough, with some boys playing in a dry concrete canal. Nearby, Veró, the woman of the title, helps her sister Josefina shoo a group of noisy kids into one car, while Veró takes off alone in the other. In a remarkable long take, she drives until the car lurches, causing her to bump her head on the windshield. Rather than cutting to what Veró hit, the camera stays with her as she sits, dazed. After a long pause she drives on, and a new framing allows us to briefly glimpse a large dead dog on the road in the distance. Soon the heroine stops and gets out of the car, walking out of focus as we stay in the car and the first heavy drops of a storm strike the windshield (below). One hint: even the exact moment when the rain starts becomes a clue to unraveling the action to come.

The rest of the film stays with Veró, who is present onscreen or off in every scene. We watch her uncertainty, caused by a concussion, but those around her barely notice, attributing her memory loss to tiredness or illness. Eventually Veró tells her husband that she thinks she has killed someone on the road. It would be unfair to reveal more, since experiencing the twists and implications of the plot should be up to the viewer.

Stylistically the film develops on Martel’s characteristic technique of shooting largely in tight shots filmed with highly selective focus. Often one must search for the one significant character. At other times, the camera lingers on Veró’s face, glancing vaguely around with a slight, defensive smile, pretending that nothing is wrong, as more significant actions by the other characters occur out of focus in the background. Often children swarm around, placing the thin thread of the central drama in the context of insignificant gestures of everyday life but making the clues all the harder to notice.

So well hidden is the plot that many viewers will mistakenly decide that it’s a film where nothing much happens. Those who engage with it will discover quite the opposite. But be warned, only a very alert viewer could figure out the plot correctly on a single viewing. I’ll admit I missed a crucial remark on the first pass.

(See also Jim Emerson’s take on The Headless Woman.)

The Middle East

Ahmad Abdalla behind the camera shooting Heliopolis.

David and I both saw Heliopolis, he because it’s a network narrative and I because it’s an interesting district of Cairo that I know only slightly. Egypt may in the past have been the main supplier of mainstream entertainment movies for the Middle East, but Heliopolis is very much an indie, made by first-time director Ahmad Abdalla with a tiny crew shooting on location for a mere two weeks.

In a rare move for this kind of narrative, the characters from the various plotlines barely intersect. Instead, Heliopolis itself is the focus. It’s a suburb near the airport that tourists drive through on their way to the central city but seldom visit. Once an enclave of foreigners, it is now is one of the main districts for middle- and upper-middle-class Egyptians. The beauty of the old buildings, some now shells and threatened with demolition, contrasts with an increasingly westernized youth culture on the streets. Similarly the characters, all with their own aspirations, suffer disappointments in the end, creating a bittersweet tone that becomes generalized to the district.

Lebanon, the Israeli film that won the top prize at the Venice Film Festival, tells a compressed story set during the first day of the Israeli-Lebanon war. It centers on a four-man team in a tank, all going into real combat for the first time. Director Samuel Maoz confines his camera to the interior of the tank for nearly all of the action, limiting our knowledge to the characters’ viewpoints (above). What we see of the war appears through the crosshairs of the mens’ scopes, though the director does not cue us to identify consistently with any of the individual team members.

The increasingly fetid interior of the tank becomes tangibly apparent as the men’s stubbly faces gleam with sweat and grime. At intervals Maoz cuts to grotesquely lyrical details of the tank’s surfaces, with oil oozing into dials or down the walls and filthy liquid on the floor rippling with the machine’s vibrations.

Many of the conventions of the men-at-war film are present, including the young man being killed just as his message assuring his parents of his safety is delivered and the novice gunner who fails to fire when he should but then kills an innocent passerby. But such conventions are renewed through the claustrophobia of the setting and the refusal to hold back in showing the confusion, terror, and savagery of war. Only the opening and closing shots, whether consciously or not an echo of Dovzhenko, offer a hint of peace.

As an admirer of Elia Suleiman’s Divine Intervention, I anticipated most seeing his new film, The Time that Remains: Chronicle of a Present Absentee. It did not disappoint, though it is less ingratiating than the earlier film. Where Divine Intervention is largely based on subtle, ironic comedy played out primarily in Tati-esque long shots, The Time that Remains mixes long stretches of pure drama with the irony. I’ve read tepid reviews that reflect a lack of patience in figuring out what Suleiman was up to this time.

There are no Arrafat-face balloons flying over Jerusalem or fantasy ninja-revenge scenes here. Instead, apparently working with a larger budget, Suleiman ambitiously sets parts of his film in 1948 and other key years of the struggle between Palestinians and Israelis. His father appears as a constant participant in that struggle (seen in dark trousers in the frame at the top). The child Elia shows up partway through and becomes a silent witness to much of this. (As in Divine Intervention, the director plays himself but never speaks.) He acts more as a sympathizer than as an active participant in the conflict, going into exile as a young man and, as we know returning at intervals to make films that comment on the political situation. Hence the “present absentee” of the title.

The older scenes include staged skirmishes and chases, with genuine suspense, before the film settles into the modern era and the humorous, sometimes blackly humorous, life of Suleiman’s aging family and neighbors. As the earlier film dealt with his father’s final illness, the new one lingers over his mother’s.

Despite the drama, there are some characteristically hilarious moments. An unarmed Palestinian man takes out his garbage and paces during a cellphone conversation, ignoring all the while an enormous tank whose gun-turret swivels to cover his every move from a few feet away. Young Palestinians dance to loud music, seen through the glass walls of a discotheque. An Israeli jeep stops outside, vainly trying to make a curfew warning heard over the din, and the soldiers inside unwittingly start bobbing their heads slightly in time to the music.

We’re off to another day of film-viewing and will post again soon.

The Headless Woman.

Vancouver wrapup (long-play version)

Our final post from this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival. Plenty to talk about, so today you get your money’s worth. Oh, wait….it’s free. So you definitely get your money’s worth.

Kristin here—

East

If Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf have been the most prestigious Iranian directors, with their features prominent at film festivals, Majid Majidi has been among the most popular. His Children of Heaven (1997) and The Color of Paradise (1999) both had international success, perhaps largely due to their focus on children and their sentimental, heartwarming stories. The Song of Sparrows (above, 2008) represents a pleasant development and is the best Majidi film I’ve seen. It’s still sentimental and heartwarming, but there’s also a great deal of humor and some highly imaginative situations that give the film more originality than the director’s earlier work.

For a start, the film puts children into supporting roles and sticks continuously with Karim, a hard-working father who strives to make extra money to replace his daughter’s hearing aid. Initially Karim works at an ostrich farm, a completely unexpected locale that generates considerable humor—until one ostrich escapes and Karim loses his job. His one asset is his motorcycle, which he turns into a cab in nearby Tehran, thereby earning good money. Meanwhile his mischievous son and his friends dream of dredging a covered pond near their village and making money by filling it with goldfish to sell.

The triumphs and obstacles that Karim and his son meet make up the bulk of the story, though the life of the tiny cluster of houses in which the main family and their neighbors dwell is charmingly depicted.

The plot of Under the Bombs involves a Lebanese divorcée returning from abroad to search for her sister  and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

and son just after the 2006 war between Hezbollah and Israel. Only one taxi driver is willing to drive her into the southern region, where bombing could re-erupt at any time; he’s from that area himself, and he’s also attracted to Zeina. This simple story, however, is not half as compelling as the environment in which it takes place.

The film opens abruptly with extreme long shots of bombs going off among residential blocks, and as the two main characters travel through scenes of devastation, there is a vivid sense of the action being staged as the events depicted were actually unfolding. One scene depicts French NATO troops landing with the first relief supplies; another shows coffins being dug out of a mass grave and handed over to grieving family members.

Director Philippe Aractingi manages to convey something of the sense of outrage that news coverage of the Hurricane Katrina disaster did in the U.S. As Zeina questions shelter inhabitants about her lost relatives, they tell their tales of losing their entire families and of being separated from loved ones. We can’t tell whether these people may be actors or actual people who have suffered the losses they describe, but a cumulative sense of outrage emerges at the Israelis’ willingness to attack residential areas in their fight against terrorists.

West

Last time I wrote about films from Haiti and Jordan. The festival continued to offer films from countries that have had little or no regular production. El Camino (2007) hails from Costa Rica, though its director, Ishtar Yasin, is Chilean-Iraqi. The narrative is spare, though not in the enigmatic art-cinema fashion of Eat, for This Is My Body. We are introduced to 12-year-old Saslaya and her younger, mute brother Dario. They live with their grandfather in a shack and scavenge in the local dump. The grandfather sexually abuses Saslaya, and the children set out to find their mother. We watch their journey progress in typical picaresque fashion as they meet people, witness a puppet show put on by a vaguely sinister old man, and wander the streets of the local town. Yet we don’t learn where their mother is, why and when she left. The exposition is minimal, as is the dialogue. Watching El Camino, one becomes aware of how much talk most films contain, since the siblings don’t talk to each other or anyone else.

Finally, nearly 70 minutes into a 91-minute film, the children take a ferry. There the other passengers exchange stories about why they are traveling. Gradually we learn that the early part of the film was set in poverty-stricken Nicaragua, and these people are trying to enter Costa Rica illegally to find work. Saslaya reveals that her mother had left with that goal eight years earlier, after their father died. At last we get some sense of the situation, but the pair’s progress is interrupted once the group goes ashore and are shot at by local authorities. Losing Dario, Saslaya wanders into a town and perhaps an unhappy future—one that may echo what had happened to her mother.

This simple story is enhanced by poetic, even at times vaguely surrealist images, such as the two men struggling to move a wooden table who keep crossing the children’s path. With so little narrative to follow, we are encouraged to focus on the hardships and occasional pleasures of a culture which seldom figures in world cinema.

I referred to the two Mexican films that I described in our first Vancouver report as melodramas. Add another  to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

to the list with Francisco Franco’s Burn the Bridges. Two teenagers care for their dying mother in a setting that seems to attract many Latin American filmmakers: a large, decaying mansion. The sister refuses to leave the house, determined to build an isolated world for herself and her brother, to whom she feels an incestuous attraction. He, however, wants nothing more to escape, especially when a tough new kid at school awakens his dawning homosexuality. The action seems a bit overblown at times; I wasn’t always sure whether apparent humor was deliberate or not. But the film and its settings are visually compelling, especially a scene in which the brother and his new friend sneak into a forbidden part of their Catholic school, passing a series of large religious paintings and finally emerging on the roof.

O’Horten is a Norwegian film from Bent Hamer, who has emerged as a film festival favorite with his  previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

previous Kitchen Stories (2003) and Factotum (2005). It’s a character study of a fastidious train engineer striving to cope with retirement; the film plays out in an episodic series of encounters that eventually lead to Horten’s acceptance of his new life. The comedy of eccentricity proceeds in leisurely, continually entertaining scenes. Apart from its mainly quiet tone and somewhat slow pace, it presents no art-cinema challenges to the audience. Norway has chosen it as its candidate for this year’s foreign-language Oscar, and Sony Classic Pictures has announced that it will release the film in the U.S. in early 2009.

Many critics have treated Terence Davies’ Of Time and the City as if it were a sort of elegiac cinematic salute to his native city of Liverpool. Despite the fact that, following the undeserved commercial failure of his excellent adaptation of The House of Mirth (2000), Davies has not made any films, he clearly retains his popularity among aficionados. In fact, however, there is plenty of criticism interspersed with the new film’s lyrical passages. Davies deplores what has become of Liverpool since his childhood there and doesn’t hesitate to assess blame, and he includes harsh comments on religion and on British royalty. He has said that he modeled his documentary on those of Humphrey Jennings, and in particular Listen to Britain (1942), though Jennings’ films had none of the bitterness on display here. Given, however, that Davies was bullied in his school, grew up gay in a more intolerant era, and has had a stunted filmmaking career, such bitterness is hardly surprising.

During Davies’s youth, brick row-houses encouraged communities among the working-class families  necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

necessary to Liverpool’s industries. Using moving and still footage from the era set to classical music, the director manages to create a poignant sense of the grim conditions these people endured. Modern footage shows these old row-houses in ruins—yet shows the council apartment blocks that replaced them to be in almost equally ramshackle shape. Davies contrasts these with some of the few remaining glorious buildings of Liverpool, mainly columned government spaces through which he cranes his camera. He also filmed candid footage of children, perhaps hinting at the one hope for the future, perhaps displaying those whose youthful memories of Liverpool are now being formed in a far less attractive city.

Of Time and the City marks a welcome comeback, one which I hope will lead to more films by Davies.

DB here:

A miscellany

The Dragons and Tigers programs continued to bring forth very impressive items. Jia Zhang-ke’s 24 City offered a meditation on newly industrializing China, in the vein of last year’s Useless. Aditya Assarat’s Wonderful Town was a prototypical “art movie” that handled a doomed love affair with sensitivity and suspense.

Especially engaging was the new offering from Brillante Mendoza, whose Slingshot I admired at Vancouver last year. In Serbis (“Service”), the Family film theatre lives up to its name only with respect to its management. For here, in the sweltering Philippines town of Angeles, the Pineda family screens porn. The movies attract mostly gay men, who service one another in the auditorium, the toilets, and the stairways. While the matriarch Nanay Flor fights a legal battle, she runs the lives of her employees and kinfolk in a milieu teetering on the edge of confusion. The Pinedas live in the theatre, so that the youngest boy must thread his way to school through a maze of transvestite hookers.

Mendoza confines the action almost entirely to the movie house. That premise recalls Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye Dragon Inn, but Serbis has none of that film’s nostalgia for classic cinema. Here movie exhibition is an extension of the sex trade, exuberant in its tawdriness, steeped in heat and sweat, prey to randy projectionists and stray goats. Almodovar might make something more elegant out of the situation, but Mendoza’s careening camera yanks us from vignette to vignette, from the complaints of the operatic Nanay Flor to her loafing husband to the lusty projectionist with a boil on his buttock. Crowded with vitality, the film can spare its last moments for a burst of reaction shots that imply a whole new layer of comic-melodramatic turpitude.

In other strands of the festival, I enjoyed Nik Sheehan’s lively documentary FlicKeR, which tells the tale of Brion Gyson, friend to the Beats and especially Burroughs. But the real star is Gyson’s Dream Machine. A turntable that spins a slotted cylinder around a lightbulb, the gadget—reminiscent of the Zootrope and other precinematic toys—proved mesmerizing to artists and countercultural fellow travelers. Marianne Faithful, Iggy Pop, and other worthies attest to the hypnotic power of the Machine, which triggered a drug-free high. Sheehan fills in a patch of important cultural history and may inspire others to tickle their alpha waves with a homemade Dreamer.

Almost exactly halfway through Steve McQueen’s Hunger lies a long dialogue scene in which IRA prisoner Bobby Sands explains to a priest why he has to launch a hunger strike. Over cigarettes the two men debate the cost of pushing tactics to this extreme. Running nearly twenty minutes and relying almost entirely on a protracted profile shot, it’s the first extended conversation in what is largely a film of bits of behavior and glimpses of a harrowing place.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Hunger starts by showing the morning routine of a guard at Maze Prison. He washes up. Stiff along a wall, he smokes a cigarette. He painstakingly folds up the tinfoil that wraps his lunch. McQueen’s oblique approach to the subject is maintained when we see a new prisoner brought in. Through him we learn of the cell walls whorled with excrement, the unannounced beatings, and the charade of providing tidy clothes for the prisoners to wear on visitors’ day.

Comparisons with Bresson’s A Man Escaped are inevitable. McQueen is less rigorous and original pictorially, assembling shots based on current image schemas (planimetric framings, selective focus, extreme close-ups, artily off-center compositions, handheld shots for scenes of violence). And he can underscore points a bit too much, as with the repeated shots of the guard’s scabbed knuckles. Still, compared with Schnabel’s conventionally daring Diving Bell and the Butterfly, the film is willing to be unusually hard on us. Through his nameless prisoners, McQueen treats both brutality and fortitude matter-of-factly. His experience with gallery-installation video seems to have encouraged him to let sheer duration do its job. A patient shot stationed at the end of the corridor waits while a guard, proceeding steadily toward us, clears puddles of urine with a push-broom.

Once Sands passes through his revolutionary catechism, the stakes are clear. The rest of the film returns to the dry, nearly dialogue-free atmosphere of the opening as Sands’ strike ravages his body. The objectivity of the opening yields to Sands’ hallucinatory recollections of his childhood as a long-distance runner. Some may see these images, including birds in flight, as clichéd sympathy-getters, but McQueen’s handling is pretty unsensational. Hunger’s quasi-geometrical structure, the sidelong introduction of horrific material, and the almost clinical treatment of Sands’ deterioration invite us to feel, but they also urge us to think about the price of sacrifice to a cause.

Genre crossovers

Some people consider the “festival movie” a genre in itself–the somber psychological drama with little external action, shot at a slow pace. The stereotype is all too often accurate, but festivals play genre pictures too. Usually these are impure genre pictures, more self-consciously artful or ambitious than multiplex crowd-pleasers. Vancouver had its share of such crossover items.

Hansel and Gretel, a South Korean horror film, played with a classic premise: the happenstance that brings someone from the normal world into a peculiar, isolated household. In this case, a superficial young man lost in a forest stumbles into the House of Happy Children. Here three kids seem to rule their passive, saccharine parents. The situation recalls Joe Dante’s episode of the Twilight Zone film, and during the Q & A director Yim Phil-sung acknowledged the influence of that movie, as well as Night of the Hunter. Brisk, fast-paced, and boasting remarkable sets—dazzlingly lit, jammed with toys and sweets, and ineradicably sinister—Hansel and Gretel could earn cult following in America. Rob Nelson has more here.

Artier, and scarier, was Let the Right One In, a Swedish film by Tomas Alfredson. Adapting Chekhov’s precept that the gun on the mantle in Act 1 has to go off in Act 3, the film begins with the boy Oskar playing with a knife at his window. Later we’ll learn that his stabbing is a fantasy rehearsal for dealing with the bullies who torment him at school. He meets Eli, a girl who comes out only at night, and their adolescent friendship/ love affair on the jungle gym of a housing block is intertwined with a series of vampire attacks on a small town. The tautly constructed script develops in gory directions that I found both unexpected and inevitable. The wintry widescreen cinematography is handsome and precise, and may well look better on 35mm than on the somewhat contrasty digital version available for the festival. It will have a limited opening in the U. S. later this month.

After School, by Uchida Kenji, is an agreeable thriller—somewhat overbusy and implausible in its plotting, but offered with a modesty and assurance that make it worth a watch. The basic situation, of a missing salaryman who may be having an affair, gains suspense by initially restricting our viewpoint to a shabby private detective. Uchida has fun with one of those misleading openings so common nowadays: you think you understand it from the get-go, but when it’s replayed it takes on a new meaning (and explains the title). The final shot, from a surveillance camera trained on an elevator, is a nicely oblique reminder of what seemed at the time a throwaway moment.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

Variety characterizes Il Divo’s genre as “Biopic, Foreign, Political, Drama,” which covers all the bases. Giulio Andreotti, long-time Italian politico, is the subject of the movie, described by an ironic friend as “one-half of the current Italian film renaissance.” The movie surveys Andreotti’s career after the Red Brigades’ murder of Aldo Moro, which triggered a wave of investigations, tribunals, and assassinations, and it concentrates on years after 1995, when Andreotti was accused of links to the Mafia. The first half-hour feels like a single montage sequence, with murders and huddled meetings whisked past us thanks to rapid cutting, swooping camera movements, and pulsating music. (The eclectic score ranges from Sibelius to Gammelpop.) Imagine the sinuous opening of Magnolia, with machine guns.

When director Paolo Sorrentino settles down to to presenting straightforward scenes, his florid technique persists (he never met a crane shot he didn’t like), but the action is dominated by Toni Servillo’s lead performance, which is weirdly showoffish in its own way. Servillo’s Andreotti is a rigid, buttoned-up fussbudget, an impassive mole of a man; only his epigrams (“Trees need manure to grow”) suggest a mind inside. The maniacally contained performance is as stylized as a turn by Lon Chaney, and as hard to keep your eyes off. Then again, given the glimpses of Andreotti in this report on the Italian response to Il Divo, the portrayal seems only a little exaggerated.

Of course there can be a straightforward genre picture here and there at the festival. The most disappointing instance I saw was The Girl at the Lake, an Italian whodunit that is only a notch or so above a TV movie. More entertaining was Welcome to the Sticks, the fish-out-of-water comedy that has become the top-grossing French film of recent years. A postal supervisor is assigned to a remote village where, he’s convinced, the hicks and the freezing cold will make him miserable. Instead he finds warm-hearted people and plenty of fun. The problem is to keep his wife from finding out how much he’s enjoying himself.

The item is hammered and planed to the Hollywood template. Plot lines: love affairs, both primary and secondary, complicated by work. Structure: four parts, with a neat epilogue that wraps everything up. Motifs: traffic cops, carillon bells, and food, often treated as running gags. Style: overall, less cutting than we might find in Hollywood (8.7 seconds average shot length), but still huge close-ups for extended passages of dialogue. In all, Wecome to the Sticks is sitcom fare that provided, I have to admit, a nice break from a lot of misery on display in the more orthodox festival offerings.

Turning Japanese

In our first communiqué, I talked about films by Kitano and Wakamatsu. I want to add comments on two more Japanese movies I saw, both of exceptional quality.

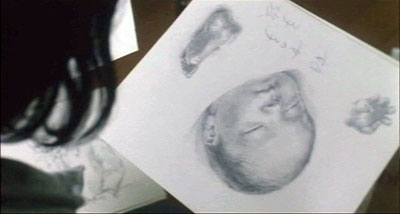

In All Around Us, Hashigushi Ryosuke (Like Grains of Sand, 1995) tells the story of a fraught marriage. The happy-go-lucky Kanao settles into a job as a courtroom artist for TV news, while Shozo, who works in publishing, is a believer in strict rules for their relationship. Their efforts to have a child end unhappily, and Shozo finds her life unraveling. Domestic troubles, amplified by tumult in Shozo’s extended family, play out while every day Kanao covers soul-destroying criminal cases, many involving assaults on children.

The mix of tender sentiments and extreme violence (offscreen, but evoked through chilling testimony) give the film a typically Japanese flavor. Hashigushi filters much of the courtroom horrors through Kanao’s point of view, so that while a defendant berates himself for not killing more people, Kanao watches a mother, and the close-up of her bandaged wrist concentrates all her grief.

The tact of Hashigushi’s handling is on display in a late sequence. As Shozo struggles out of her depression, her family gathers for what apparently will be her grandfather’s final moments. The adults assemble to discuss the situation while children play in a room behind them. Kanao shows them sketches that they take to be of the father in his final moments.

During their discussion, the adults are distracted by the children shattering an urn in the background.

Here Hashigushi uses staging techniques I’ve discussed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. Kanao’s display of his sketch favors us; it is centered and frontal. Then, after blocking the children’s play for some time, Hashigushi reveals it—centered and exposed as the adults in the foreground turn to look.

Then most of the family leaves. Hashigushi tracks in slowly to the mother’s confession of her misdeeds, and he ends the shot with a close-up of Shoko.

In a film in which the camera moves seldom and without much fanfare, this creates a simple, powerful impact and refocuses the drama on the psychologically fragile Shoko.

The film I’ve admired most across the festival is, predictably, Still Walking by Kore-eda Hirokazu. It relies on a simple situation. Grandpa and grandma celebrate a son’s death anniversary by a visit from the families of their son and daughter. Across a little more than a day, memories resurface and old tensions are replayed.

Everything unfolds quietly, and the pace is steady: none of the histrionics, both dramaturgical and stylistic, of the Danish Celebration and other psychodramas of dysfunctional families. Still Walking is a classic Japanese “home drama” in the Ozu mold. The conflicts will be muffled and nothing is likely to break the placid surface.

In a stream of vignettes Kore-eda brings each family member to life, displaying an easy mastery in shifting attention from one to another. Gradually he assembles a group portrait of a domineering father, a good-humored mother, a slightly daffy daughter, a son always compared unfavorably to his elder brother, and in-laws striving to be well-received by the grandparents without alienating their spouses. The spirit of Ozu, particularly Tokyo Story and Early Summer, hovers over specifics: a dead brother is invoked, the family poses for a picture, and the patriarch, a retired doctor, has a clinic in his home.

Kore-eda doesn’t get as much credit as he deserves; he’s often overshadowed by extroverts like Miike Takeshi. That’s partly because his is an art of quietness, shown perhaps in its most extreme form in his first feature, Maborosi (1995). At the time I thought it was only one, albeit exquisitely wrought, version of the “Asian minimalism” that sprang up in Taiwan, Japan, China, and even a bit in Hong Kong. I suspect that this trend was largely due to Hou Hsiao-hsien’s masterpieces like Summer with Grandfather, Dust in the Wind, and City of Sadness. A Japanese critic told me that indeed Maborosi was criticized as being too Hou-like.

Now, after After Life, Distance, Nobody Knows, and Hana, Kore-eda has moved to the forefront of Japanese cinema. It seems to me that he maintains the classic shomin-geki tradition of showing the quiet joys and sadness of middle-class life while also plumbing the resources of “minimalist” mise-en-scene.

In Still Walking he works in an engaging, unfussy way. He lets us get to know and like his characters, feeling neither superior nor inferior to them. He builds up his plot more through motifs than dramatic action; a good example is the pop song that the mother loved and that gives the movie its title. The technique, spare but not austere, enforces the relaxed pacing. The film has only around 375 shots in its 111 minutes. While there are plenty of reaction shots and close-ups (the first shot shows women’s hands scraping radishes), some scenes play out in long takes rich in detail.

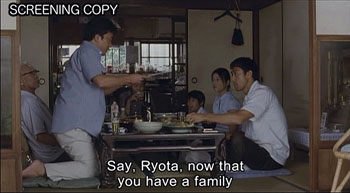

For example, in a three-minute shot early in the film, most of the family is gathered around a table.

The brother-in-law, a used-car salesman, goes out to the garden to play with the children.

Now the family members discuss the dead brother’s widow, who doesn’t come to family gatherings.

When the father declares that a widow with a child is harder to marry off, he is obtusely insulting his son Ryota’s new wife. Kore-eda marks the disruption with a cut to a reverse angle.

This generates another long take, in which Ryo’s wife Yukari deflates the tension by saying she was lucky to get him. The women then rise and clear the foreground, somewhat as the brother-in-law had by going into the garden. As the family talks, we can see him in the distance helping the kids break open a melon.

Ryo talks about his job restoring paintings. It’s clear that the father disapproves of it, wishing that Ryo, like the deceased brother, had taken up medicine. Kore-eda keeps the garden action as a secondary point of interest by having Ryo glance off occasionally.

But Ryo’s explanation of his job is cut off by the father’s abrupt rise and walk to the doorway, ordering the kids to stay away from one plant.

When the father returns to the table, the nearly two-minute long shot is replaced by a series of singles as Ryo tries to explain his work.

These shots employ one of Ozu’s staging tactics, settling two characters not directly opposite one another but one space apart. The camera seats us across from each one. As a result, the men can be posed frontally, while now we can watch where their glances go—most often, downward. The new setups let us see that the father and son don’t look at each other much.

Instead of moving to these singles right away, as most directors today would, Kore-eda has saved them as a way to articulate the next, more intense phase of the drama. It is arguably a less ostentatious way to raise the tension than the prolonged track inward that Hashigushi uses in All Around Us. (Then again, Hashigushi employs that technique at a climactic moment, while this scene we are still rather early in Kore-eda’s film.) The point is the simplicity and delicacy with which Kore-eda deploys traditional elements of craft.

It wouldn’t be fair to offer a more intensive analysis of this trim work, since it has yet to be widely seen. In the best of all worlds, it will get an American theatrical release.

In all, another wonderful Vancouver festival. See you there next year?

FlicKeR.

C is for Cine-discoveries

Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers!

DB here:

Kristin and I think of Brussels as a gray city—gray skies, gray pavements, gray buildings, even gray, if often fashionable, clothes. It isn’t usually a fair description, though. In the twenty-plus summers we have been visiting, many days have been bright. I suppose our impression comes chiefly from one rainy fall we spent here in 1984, on a Fulbright research grant. Still, the public monuments bear us out, especially the Palais de Justice: except for its gold dome, it is gray, and has been encased in gray scaffolding for as long as we can remember.

Indeed, Brusselians assure us that the scaffolding will never go away because it’s holding the Palais up.

The gray motif continues this summer; during my visit, there have been almost no sunny days, just rain and chill. To prove that Belgians have stayed loyal to their favorite color, I took a shot of a new piece of public architecture near the Central Station: a half-circle of tipped-over pyramids that are, ineluctably, gray.

Still, the movies provide my light and color. I talked about Brussels as one of the great film cities in last year’s entry. I found further proof in a 2003 Marc Crunelle’s Histoire des cinemas bruxellois (in a series announced here), a small book with some fine pictures, one of which you will find at the end of this entry.

As usual, my host was the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. The archive offices remain in their splendid old building, the Hotel Ravenstein, but the new museum complex is still under construction. So the screenings continue to be held in the ex-Shell building, a piece of postwar Europopuluxe that I seem to enjoy more than most of the locals.

During my days, I watch films (very, very slowly) in the archive vaults; more about that project in my next entry. At night the event was Cinédécouvertes, the annual festival of new films that don’t yet have Belgian distribution. That festival, going back decades, has now been attached to a bigger event, the Brussels European Film Festival, which this year began on 28 June. BEFF showed thirty new titles, plus eight older items in open-air screenings, and it gave several prizes.

Kristin and I were in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato and so I missed all of these, including the big Flemish film of 2007, Ben X. But Cinédécouvertes, running on during the BEFF, had its second and final week while I was in town. Films screened were competing for a 10,000-euro prize to be awarded to a distributor that would pick up the film. In addition, the venerable L’Age d’or prize would be awarded to a film that maintained the spirit of Buñuel’s scandalous masterpiece.

Herewith some notes on what I saw, and the prize results. Of course on the day I posted this, the sun came out.

Women, prep school, and manga

Cargo 200.

The two Iranian films in the program were earnest but varying in quality. Unfinished Stories (Pourya Azabayjani) is a network narrative following three women across a single night. A suicidal teenager doesn’t return home; her path crosses with that of a wife cast out by her husband; and she in turn brushes past a young woman who tries to smuggle her newborn baby out of the hospital. The situations are engagingly melodramatic, but the links among them (a footloose soldier, a compassionate taxi driver, an enigmatic old man) seemed to me forced, and as is often the case in these tales, the problem is how to conclude each story line in a satisfying way. The use of sound was very fresh, however. I especially liked the teenager’s obsessive replaying of taped conversations with her boyfriend. Often these “auditory flashbacks” are played over a black screen, and they come to exist as discrete, almost virtual scenes.

I like it when a film begins with a sharp, defining gesture, and Three Women (Manijeh Hekmat) had one. In close-up a car drives up to a tollbooth and the driver’s hand tosses a cellphone into a Charity Box there. Someone is on the run and cutting ties, but we won’t find out more for some time.

The first stretch of the movie concentrates on Minoo, a divorced professor and expert in Persian textiles. A rug dealer has promised to keep a precious carpet in the care of her museum, but he changes his mind and tries to sell it. In a fit of temper she grabs the carpet from its owner and takes it to her car, where her somewhat senile mother waits patiently for a trip to the hospital. Then the old lady vanishes. The emphasis shifts to Minoo’s daughter Pegah, who has set out on her own. The maddening Tehran traffic of the early scenes gives way to the empty quiet of the countryside. In the second half of the film, a favorite theme of Iranian cinema—the urban intellectual confronting rural life—is played out vividly when village elders debate whether to stone a woman who has had an abortion.

Like many of the best Iranian films, Three Women tells its story with dramatic force, offering robust conflicts and a degree of suspense rare in arthouse fare. Manijeh Hekmat, who made her name with Women’s Prison, manages the story threads skilfully, creating a continuous revelation of backstory and hints about how the tale will develop. I especially liked the way Minoo gradually realizes that she has had no idea how her daughter is living. As Alissa Simon points out in her perceptive review, Hekmat can spare time for a subtle composition as well. The ending came as a quiet surprise, deflating some dramatic issues but emphasizing the comparative unimportance of carpets, cellphones, and pop music in the face of the deeper problems facing Iranian women.

Add another woman and you have Adoor Gopalakrishnan’s Four Women. The quartet of stories, all adapted from literature and evidently set in the 1940s and 1950s, shows the fates befalling women in different roles, each identified with a title: The Prostitute, the Virgin, the Housewife, and the Spinster. Not much fun to serve in any of them, it turns out. The film has a sharp eye for details of local life and ceremonies, an ambition helped by the high-definition format: a slow-moving river is off-puttingly scummy. A little didactic and schematic, but it’s enlivened by a long sequence of a husband who methodically and endlessly eats everything put in front of him, with a seriousness he cannot bring to his marriage. The sequence starts in bemusement, moves to humor, and persists to the threshold of nausea.

The Argentine La sangre brota (Pablo Fendrik) was a little reminiscent of City of God in its relentless handheld assault on your senses, with the camera grazing faces and people racing in pursuit of drugs and money, with a beleagured taxi driver trying to do the right thing. La maison jaune (Amor Hakkar), from Algeria, appealed more to me. How much we owe neorealism! Quietly and simply, Hakkar tells of a father learning of his son’s death, fetching the body home for burial, and then trying to find a way to relieve his wife’s grief. So he paints his house yellow. Quiet and moving and not as simple, in story or pictorial technique, as it might sound.

Antonio Campos’ Afterschool (US) is a very assured first feature about drug-overdose deaths in a prep school. The story is told almost completely through the consciousness of Rob, an introspective and awkward freshman who indulges in internet porn. Passive to the point of inertia, Rob remains largely a mystery. This effect is often due to Campos’ bold use of the 2.40 widescreen frame, which often excludes some of the most important dramatic information. People are split by the left or right edge, or are decapitated by the top frameline, so we must strain to listen to the conversation and catch glimpses of the characters. This may sound arbitrary, but Campos finds ways to motivate the lopped-off compositions. One shot, when the parents of dead students record their thoughts on video, is one of the strongest pieces of staging I’ve seen this year. Unlikely to get U. S. theatrical release, if only because of its pacing, Afterschool marks Campos as definitely a director to watch. It won one of the two top Cinédécouvertes prizes.

The other top prizewinner was Yoshida Daihachi’s Funuke, Show Some Love, You Losers! It’s another insane Japanese family movie—that is, the family is insane, and the movie acts the same way, out of sympathy or contagion. After the parents are killed trying to save a cat from an oncoming truck (nice overhead shot of bloody skid marks), a new household takes shape. There’s the phlegmatic brother Shinji, his maniacally cheerful wife, his adolescent sister Kyomi, and his sister Sumika, who comes to stay after failing to make it in Tokyo as an actress. Family secrets emerge. Sumika starts turning tricks and Kyomi draws violent manga inspired by Sumika’s adventures. The comedy turns blacker when Kyomi’s comic books become best-sellers and all the family problems regale the reading public. With some scenes shot in high-contrast video, as if they were TV episodes, and a climax that blends film and manga, panel by panel, the film’s style is as all over the map as the characters and their complexes. Good dirty fun from the title onward.

The L’Age d’or prize went, deservedly, to Cargo 200 from Russia. Another black comedy, but one that gets blacker and less funny as it goes along, it becomes sort of a post-Glasnost’ Last House on the Left. (Seriously, maybe there’s an influence of Saw and Hostel here, with hints of Faulkner’s Sanctuary.) Set in 1984 and stuffed with retro clothes, hairstyles, and music, the plot spins crazy-eights around the corpse of a returning Afghan war hero; a teenager trying to buy homebrew vodka; a bootlegger who keeps a Vietnamese refugee as an assistant; a small-town policeman with a penchant for voyeuristic sex; and a professor of dialectical materialism who wanders, blinking, in and out of the lurid plot twists. Director Alexei Balabanov, who did the pioneering rough genre picture Brother (1997), gives no quarter here.

Strength in simplicity

Albert Serra directs the three kings in El cant dels ocells.

My three favorites were all resolutely unfancy. Shultes, a Russian item by Bakur Bakuradze, is a minimalist study of a pickpocket. Shultes lives with his mother, gives some of his loot to his legit brother, and takes up with a boy whom he tutors in thievery. At slightly over 200 shots, the movie is staged, shot, and cut with a precision that reminded me of Apichatpong Weerasethakul (Syndromes and a Century). On the inexpressiveness scale, Shultes, with eyes and mouth too small to fill up much of his face, makes Bresson’s pickpocket look positively other-directed.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

As with all movies about stealing, the pleasure lies in trying to figure out the plan and spot the telltale moves—sort of like the misdirection of a magic act. Here the drama is cunningly contrived. What is Shultes writing in his little brown book? Who is Vasya? What’s his big plan? The plot jumps a level when we realize that all we’ve seen is a flashback, and the ensuing conversation puts things in a startling perspective. Our blankly amoral protagonist even becomes a shade sympathetic. Too rigorous and unemphatic to be an arthouse import, I fear, but ideal for a festival.

Shinji Aoyama is best known for Eureka (2000), which won a prize at an earlier Cinédécouvertes. Sad Vacation is one of those films that try to do justice to the ways in which humans become tangled in relationships based on acquaintance, momentary bits of kindness, and sheer chance. Kenji helps smuggle Chinese workers into Japan, but when one dies, Kenji takes the orphan boy under his wing. Soon characters and connections proliferate. There is the salariman and his dumb pal searching for the runaway Kozue. Kenji cares for a slightly daft girl, and he becomes romantically involved with the bargirl Saeko. Accidentally he finds the mother who deserted him, and he joins her new family, complete with mild-mannered father and rebellious brother. Always hovering around are several men and women who work for the father’s trucking company—people rescued, it’s implied, from crime or neglect.

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Aoyama manages the crisscrossing relationships delicately, without losing sight of the fact that behind Kenji’s laid-back appearance is a boiling desire to avenge himself on his mother. But she’s his match. A woman of smiling serenity, or smugness, she seems infinitely resilient. The final confrontation of the two, in a prison visiting room, has the giddy sense of one-upmanship of the prison visit in Secret Sunshine. Things turn grim and bleak, yet Sad Vacation manages to feel optimistic without being sentimental; even a flagrantly unrealistic soap bubble at the close seems perfectly in place. I notice that Aoyama has made nearly a film a year since Eureka; why aren’t we (by which I mean, I) seeing them?

Some films, like those of Angelopoulos, seem to spit in the face of video. You can’t say you’ve seen them if you haven’t seen them on the big screen. Such was the case with my favorite of the films, The Song of the Birds (El cant dels ocells, 2008) by the Catalan director Albert Serra. It merges an aesthetic out of Straub/ Huillet—black and white, very long static takes, drifts and wisps of action—with a joyous naivete recalling Rossellini’s Little Flowers of St. Francis. Serra’s film also reminded me of Alain Cuny’s L’Annonce fait à Marie (1991) and one of the greatest of biblical films, From the Manger to the Cross (1912). All make modest simplicity their supreme concern.

We three kings of Orient are . . . well, definitely not riding on camels. We are in fact trudging through all kinds of terrain, scrub forests and watery plains and endless desert, to visit the baby Jesus. We are also quarreling about what direction to go, whether to turn back, and why we have to sleep side by side so tightly that our arms go numb. And in an eight-minute take we are struggling up a sand dune, vanishing down the other side, and then staggering up again in the distance.

The three kings aren’t characterized, and they are sometimes unidentifiable in the long-shot framings; only their body contours help pick them out. Intercut with their non-misadventures are glimpses of an angel (whom they may not see) and stretches featuring Joseph and Mary, who caress a lamb. Eventually the infant Himself puts in an appearance, burbling. When the kings finally arrive, one prostrates himself. The image settles into a tidy, unpretentious classical composition and we hear the film’s first burst of music, Pablo Casals’ cello rendering of the folk tune Song of the Birds.

The kings get a chance to bathe in a scummy pool before returning home. Off they trudge. “We’re like slaves!” one complains. In a final shot that would be sheer murk on a DVD, they swap robes and set off in different directions. Did I see them embrace one another? Did they murmur something? I couldn’t tell for sure. Night was falling and they were far away.

Like Casals’ cantata El Pessebre, The Song of the Birds gives us a Catalan nativity. The simplicity is genuine, not faux-naif, and the humility doesn’t preclude humor. Although the shots are quite complex, the spare surface texture invests a familiar story with a plain, shining dignity. Discovering films like this, which you will never see in a theatre and could not bear to watch on video, makes this ambitious festival such a worthy event. It maintains the heritage of one of the world’s great cinema cities.

Next up: A report on films I’m watching at the archive’s vaults on–no kidding–the Rue Gray.

The Metropole, Brussels, 1932.

Thanks to Jean-Paul Dorchain of the Archive for help in finding illustrations. And apologies to readers who came here and found only a stub earlier. An internet gremlin somehow purged the first version of this entry a few hours after it was posted.