Archive for the 'National cinemas: Spain and Portugal' Category

Vancouver: Stories, spliced and stacked

Sarita (2019).

DB here:

Humans love stories, the more the better. As a result, many storytellers find ways to bring distinct story lines together. The most common way is to link them, through subplots involving major and minor characters. Viktor Shklovsky urged us to think of folktales, novels, and plays as “braided” out of several story lines. At other times, the stories are bracketed within a bigger plot. A character tells others about incidents in childhood, or characters tell completely detachable tales, as Scheherazade and Chaucer’s pilgrims do. Instead of braiding, we get embedding within a frame situation.

I started to think again about these options watching four films at the always exhilarating Vancouver International Film Festival. All were engaging, partly because they often mixed comedy and drama in rewarding ways. They also offer a nice menu of creative possibilities, exploited by ambitious filmmakers.

Screen life

An omnibus film can offer a frame story, as the British classic Dead of Night does, but most modern ones simply line up one tale after another, in blocks. Essentially these are short stories, and they tend to follow literary patterns.

One option is the “snapper,” the plot consisting of twists and a sting in the tail, a surprise ending. Edgar Allan Poe may have invented this format, O. Henry canonized it, and Roald Dahl gave it a grisly tenor. Diverting examples of the surprise-ending story can be found in the omnibus Spanish film Tales of the Lockdown (2020).

All five modules are comic, though sometimes in a macabre vein. Produced during the COVID-19 lockdown, somehow staged and shot remotely, each episode is cleverly scripted and elegantly directed. In one, a reclusive Milquetoast is pressed by an aggressive neighbor who wants to sell him a plan to expunge “bad vibrations” from his apartment. The Feng Shui saleslady gets more than she bargained for when she learns the source of those vibes.

In another, an aspiring hitman recruited by The Agency gets a remote tutorial from an experienced killer, who makes him practice techniques on a teddy bear and the dogs he snags from the neighborhood. A third, gentler episode is still tricky: we’re led to presume some things about a couple that turn out to be not valid–at least, not until the end. Sorry to be so elliptical, but films like this oblige you to avoid spoilers.

The most straightforward comedy concerns a woman auditioning by video for a TV part, aided by her husband who decides he could get a role as well. For a local audience, the fact that she is played by star Sara Sálamo and her actual husband, a Real Madrid football player, doubtless adds to the fun. The last episode, a black comedy, presents a rich couple’s extreme reaction to a tenant strike in one of their buildings.

The filmmakers have found many nifty ways to exploit the limited viewpoint enforced by lockdown. Naturally, remote conversations take place over laptops, which motivates minimal change of setting and little need for elaborate action scenes, or even ordinary staging in interiors. Offscreen action is likewise conveyed minimally, just by speech or noise in the world outside. The funniest moments in the fifth episode concern the rich couple learning they’ve received a “package” which we never see and must assume is problematic, since the thug on speakerphone says it’s “middle-aged.”

Confined settings have in effect created five “chamber plays” of the kind I’ve talked about before. This constraint allows directors to design and dress settings and find playful compositions to accentuate the plot twists that keep us glued to the screen.

In all, Tales of the Lockdown is a display of light and lively cinema craftsmanship. It’s heartening to see creative energy maintained in pandemic conditions. It premiered on Spanish Amazon Prime and would be worth looking for on that platform in other markets.

Food, memories, and the future

The major alternative to the twisty snapper tale is the “slice of life,” the muted drama of a situation that may change little or not at all. Here the emphasis falls on characters–their relations, their reactions, and their sensitivity to one another. The classic examples come from Chekhov and from Joyce’s Dubliners, but they’re also prevalent in what used to be thought of as the classic New Yorker short story of John Cheever or J. D. Salinger.

Pensive incompleteness of this sort well suits the Hong Kong film Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down (2019). Directors Kate Reilly and Leung Ming-kai have made three of the four stories fictional, treating them as vignettes of restrained realism. A Malay caregiver takes a grandma on an afternoon outing. She wants to go to a political rally where rice will be given out, and she hopes to meet old friends from her village. The old lady is forgetful, and her chatter recycles memories of her youth. The trip turns out to be something quite different, but she doesn’t realize it. The caregiver’s concern turns a simple duty into an act of kindness, as well as a tactful political gesture.

In “Toy Stories,” two brothers meet in their mother’s toy store, which is being sold, contents and all. As with the first episode, memory comes to the fore. The men play games and quarrel about the Power Rangers figures they loved. One, who has a son, tries to find something educational to bring back. He is barely hanging on financially, while his brother has lost his job. A final scene shows a bit of development in their situation, and gives room for a little hope; it’s the only episode that ends, “To Be Continued.”

The third episode is a wistful, Wongkarwai-ish almost-romance. Ruth, an American Caucasian, has come to teach in the school where John, a Chinese, teaches economics. Both are on their way elsewhere–Ruth to teach in Beijing, John to “try something different” in America. They bond over food. (Of course; this is a Hong Kong movie.) From their meeting at a vending machine to the street stalls and cheap restaurants they explore, Ruth learns of the joys of salted egg, pig intestines, and above all yuen yeung, a uniquely local mixture of tea and coffee.

These three stories quietly evoke distinctive Hong Kong culture–the older generation’s memories of moving to the colony, the Gen-X absorption in popular culture, and the particularities of local cuisine. The fourth segment builds on these in looking toward the future.

It’s a documentary showing the barista and cat-lover Jessica Lam running for a local council seat. She faces a pro-Beijing candidate, but she’s more grassroots. She’s also an amateur and runs a fairly minimal campaign. Although she does denounce police violence against demonstrators, the main force of this sequence is the portrait of a sincere young woman trying to improve neighborhood life. This is the only episode with a climax, the election-day vote count. And there is a twist when Jessica gives her final verdict on the results.

The omnibus format has proven a strong option for contemporary Hong Kong cinema, as witness the powerful Ten Years (2015). Memories to Choke On addresses not state oppression, as that did, but the politics of everyday life, the ways in which the sagging economy and the Chinese takeover ripple through the lives of ordinary people. The impact is quite specific: local audiences would know that the actor playing John in the third segment is Gregory Wong Chung-yiu, who is at risk of years of imprisonment for participation in a demonstration. Each story is a telling vignette, a slice of Hong Kong life that will engage overseas audiences and instill a mixed nostalgia in everybody who has ever visited what Chuck Norris in The Octagon (a very different movie) calls “the place.”

Camp as community

The option of embedding the stories within a frame can blur their edges more or less. Sarita (aka Tell Me Who I Am; 2019), an Italian film about refugees from Bhutan living in a Nepalese camp, could have been a straightforward documentary about problems of exile and resettlement under the auspices of the UN. Instead, it blends real-life stories of the refugees with a young girl’s quest to recover her memory. In what filmmaker Sergio Basso calls a more fanciful and energetic approach than a “tragic” documentary would give, we get a film close to magical realism–with DIY Bollywood musical numbers.

Sarita is more or less happy in the camp. She has friends to play and dance with, a school to attend, and every opportunity to worship her favorite god Shiva. But she often quarrels with her parents and wonders why they can’t go back home, a place she has never known. Shiva wipes Sarita’s memory, endowing her with the drive to ask questions of everyone around her. In this Rip van Winkle device, we are introduced to camp routines, as well as the history of her displaced neighbors.

Sarita visits her beloved teacher, only to find that he is often laid low by his injuries from torture sessions. People tell her of ethnic cleansing in Bhutan, of disappeared relatives and political oppression. Deciding that “building my future is easier than desiring my past,” Sarita turns to her immediate prospects. But her sister tells of the hardships of getting a university education. Taking her grandma to be treated for diabetes, she learns of people sleeping in a clinic as they wait days for treatment.

After the family is assigned a home in Oslo, she acquires a super-8 camera and cassette recorder and begins to document the life she will leave behind. Now the world she rejected seems precious. After Sarita has gone, we see her grandmother and those left behind lingering at a tree, studying mementos of their departed neighbors.

Counterpointing the harsh realities of daily routines and homesickness are moments of song and dance, in bursts of brilliant color and gymnastic choreography. We also get fantasy scenes, satires on overeager bureaucracy (the resettlement officer is a hyperactive Gene Kelly wannabe), and signs that youthful exuberance can’t be contained by drab regimentation. We hear “There is no childhood here” on the soundtrack as kids are shown inventing games and playing jacks with pebbles. The ending, however, has the poignancy of pure realism (even though it’s fictitious).

This film is an extraordinary achievement. Basso and his colleagues made it over ten years–filming without electricity and no funding from national governments or NGOs. Yet the minimal conditions enabled close collaboration with the camp residents. Seeing the children’s dances inspired Basso to make it a musical, and he gained access to local leaders. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect, Sarita even appears to interview the head of the resettlement office. Although the performers had some coaching from a theatre director and a choreographer, they clearly have natural gifts, particularly Sasha Biswas, who carries the film.

In the wake of the coronavirus, seventy Italian independent cinemas cooperated in making Sarita available on streaming platforms. There, Basso reports, it has found an encouragingly large audience. Another item to look for on the streaming menu in your area!

Visions of the good life, words of disquiet

One more film about memory, but now the memories themselves are captured on film. And the stories aren’t sealed off in blocks or gently embedded in a wider frame. They’re stacked.

Again, to say too much would soften your efforts to come to grips with the teasing, hypnotic My Mexican Bretzel (2019). Think of it as layered, like a cake.

The image track consists of a Swiss family’s home movies from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In luscious color we see a couple leading a European life of leisure: summers on the beach, winter skiing, tours of postcard capitals, yummy meals with friends in open-air restaurants. The husband, a genial, brawny fellow, clowns for the camera, but most screen time is given to his wife, a willowy brunette with a radiant smile. The landscapes might have come straight out of Holiday, that oversize American magazine dedicated to worldwide vacationing.

The next layer is a written text, purportedly a diary of Vivian Barrett. This tells of the marriage. Vivian traces the efforts of husband Leon to make and market an antidepressant. Leon’s love of flying during the war has translated into his urge to travel widely, especially on his luxurious yacht. But as the years pass, Vivian starts to record her worries, her dissatisfactions, and the temptation of taking a lover. Her musings are interrupted by remarks she finds in an untitled book by the Indian guru Kharjappalli. (Sample piece of wisdom: “God also doubts your existence.”) The couple’s lives form the outline of an Antonioni film.

Léon is making a record too. He’s wielding the Daddycam as he documents all those vacations and breakfasts and views of Manhattan, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and aqueducts. Vivian has misgivings (“If you film, you don’t have to live”) but learns to use the camera herself, and even steer the yacht.

Finally there is an exceptionally discreet effects track. The home-movie scenes are eerily silent because there’s no voice-over, but occasional noises are dubbed in, and very rarely there’s a snatch of music. On the whole, the absence of musical cues for emotion renders the pictures and the diary texts all the more powerful. (Compare the emotional tug of Jóhannsson’s score for Last and First Men, a film that also “overwrites” mysterious visuals with a text sourced to a woman.) The result is a dry, unsentimental treatment of a crumbling marriage in the midst of Europe’s postwar boom.

Out of 29 hours of found footage Nuria Giménez and her colleagues have fashioned a fascinating film that is at once pure documentary and creative fiction. I like to think of it as another way to assemble a narrative–at one level simple chronology of a cosmopolitan couple’s life, on another the hidden story of voyages to Italy and elsewhere. I kept seeing the ghosts of Bergman and Sanders in this couple on the modern Grand Tour.

I knew about none of these films before encountering them at VIFF, which is of course one reason we cherish this and all other festivals. Granted, there’s reassuring pleasure in seeing the latest accomplishments of established and esteemed old hands (here Ozon, Petzold, Vinterberg, Rasoulof et al.). Just as valuable, though, is the jolt of seeing newcomers present beguiling variants on familiar traditions. Three of these films, as far as I can tell, are first features, and they offer fresh takes on stories we thought we’d seen before.

All are graced with sharp cinematic intelligence and offer pointed commentary on lives lived now and back then, close to home or far away. All remind me of why this VIFF wing is called Panorama. Every movie widened my vision.

Thanks, as usual, to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival. Thanks as well to programmer and consultant Shelly Kraicer for background on Memories to Choke On.

You can sample the films in their trailers: Tales of the Lockdown is here; Memories to Choke On is here; Sarita is here; and a particularly shrewd one for My Mexican Bretzel is here (incorporating, I think, footage not in the film). Giménez’s film won the Found Footage Award at Rotterdam. If you insist on knowing about how her film was made before seeing it, you can check this Film at Lincoln Center interview.

I hope other festivals, and streaming services, and even theatres will pick up all these films for wide distribution.

My Mexican Bretzel (2019).

Venice, virtually

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

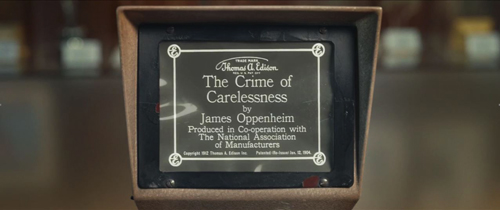

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Attachment anxieties at the Vancouver International Film Festival

DB and KT, front row center, at the screening of The Lighthouse. Photo by Shelly “Sales Agent Cinema” Kraicer.

DB here:

Storytelling cinema depends on characters, and our relations to them. At the level of individual scenes, we can be more or less restricted to what they experience; we can know as much as they do, or more, or less. Across a film, the filmmaker can attach us consistently to one or two characters, or instead roam freely among many viewpoints. And within a scene, the filmmaker’s choice of camera placement can put us “with” one character or another.

In other words, narrative cinema 101. But it’s worth remembering that these are forced choices. As a filmmaker, you can have restricted or unrestricted access to characters, but at every moment you have to choose one or the other. How objective or subjective will you make your presentation? Will you limit your camera setups or go for ubiquity–that tendency to give us shots divorced from the immediate situation? Examples are a drone-delivered image above a city, or that sudden high or low angle that calls our attention to a detail the characters may have missed.

Three films at the Vancouver Film Festival presented a nice menu of attachment options–ways in which we can be tied to our protagonist. All are well worth your attention, so without getting too much into spoilers, I’ll use them as an occasion to study how these forced choices are handled creatively.

The party’s over

Take as a midrange example The Realm (El Reino, 2018), a Spanish political thriller directed by Rodrigo Sorogoyen. Manuel López Vidal is a brisk, no-nonsense functionary enjoying the good life thanks to the corruption of his party. He and his colleagues, the Amadeus Group, meet regularly over expensive meals to plan their schemes of influence-peddling and money laundering. They tease their fastidious accountant about his meticulous ledgers, but those records will become important to Manuel when one colleague leaks incriminating audio tapes of Manuel’s dealmaking. There’s an orgy of document shredding, damage control among the party’s top brass, and the growing likelihood that Manuel will go to jail.

The screenplay restricts nearly all the action to Manuel. This method is established at the start, when a long tracking shot follows him from the beach as he strides into an Amadeus lunch. Thereafter, we’re with him as he learns of the danger he’s in and mounts one tactic after another to save himself. At a couple of moments the camera lingers on his colleagues’ reactions after he’s left the scene, but on the whole we’re firmly attached to him. Some virtuoso long takes, including a ten-minute shot that follows Manuel’s frantic search for the ledgers, virtually fetishize our adhesion to the protagonist.

By and large, the presentation doesn’t delve into his mind. The throbbing techno score conveys his growing panic as he strides from one confrontation to another, but we get no voice-overs, or flashbacks, or mental imagery. And we don’t see Manuel confide his plans to others (although he seems to have told his wife some of them offscreen). This degree of objectivity allows more suspense, as his schemes to save himself unfold in the moment. We must figure out why he’s bracing one colleague, or bursting into a friend’s home in the course of a teenage party. His manic resourcefulness is all the more impressive when he keeps dodging new problems, often revising his plan on the fly.

It’s no easy feat to maintain tension across two hours, especially when we’re asked to invest our sympathy in a corrupt politician, but The Realm manages it. It’s achieved partly through the trim, crisp performance of Antonio de la Torre but also through plot and style: the refusal of omniscient narration (say, showing us the police or party officials tracking him) and a mild degree of camera ubiquity that accentuates the character’s plight, whether in a meeting or all alone.

The Realm is a good example of how manipulating character attachment can strongly engage the audience. We know just enough to understand Manuel’s crisis, but without access to his mind, each scene can yield a surprise when he comes up with a new survival stratagem.

A lot from a little

I hadn’t really considered the Dardennes brothers “minimalist” filmmakers, but seeing Young Ahmed brought home to me how strictly they’ve limited their cinematic palette. Given their emphasis on actors and faces, you might think they rely on the sort of “intensified continuity” on display in modern film and television. Yet they’re far more purist than that, and they take objective presentation further than does Sorogoyen.

They seldom use long shots, let alone establishing shots: a scene starts in medias res with character action, shot from quite close. Filming in handheld long takes, they avoid shot/reverse-shot cutting, either panning between participants in a dialogue or simply framing them in tight two-shots.

The Dardennes minimize camera ubiquity. Not for them the picturesque, distant shots that The Realm sometimes provides. In a car carrying two passengers, the camera isn’t lashed to the hood or filming alongside; it’s in the back seat.

True, cutting yields some ubiquity. When Ahmed’s teacher pursues him through a classroom, she runs ahead of us but then, in the next shot, she catches up with him as he’s about to leave the building.

Like most cuts, it’s an instantaneous change of position that a real observer couldn’t execute. Still, this frame-edge cut creates simple continuity, driven by dramatic necessity and barely noticeable. The cut is softened by a staging that neatly settles into a standard over-the-shoulder setup.

Apparently uninterested in pictorial composition, these filmmakers simply center their subjects in undistinguished framings. No shot becomes strikingly lit or framed. There’s no nondiegetic music, and the soundtrack is subdued; of all modern filmmakers, they benefit least from surround channels.

As in The Realm, the Dardennes’ minimalist approach works well in tying us to the protagonist, while also denying us direct access to his mind. Ahmed, an adolescent in Liège, has given up video games for fundamentalist Islam. Convinced by his imam that his classroom teacher has become an apostate, he decides to take action against her.

His plans emerge wholly through his actions. Without benefits of voice-over, subjective sequences, or flashbacks, we must infer how he will respond to the demands of the Qu’ran as he has been taught to understand it.

The Dardennes’ objectivity doesn’t make the plot hard to follow. A dozen minutes into the film, the premises are clear, the main characters (Ahmed’s mother, his imam, his teacher) are delineated, and Ahmed’s motivation is established. At the half-hour point, his mission is launched. Apart from the ellipsis I mentioned, everything that follows stems from the dramatic premises. And however horrifying Amed’s plans may be, the wistful, pursed-mouth young actor Idir Ben Addi is mesmerically angelic. His glasses make him look adorable.

The style also keeps everything clear. The texture is close to that of documentary filmmaking, but of course the Dardennes’ films are scripted and staged. There’s a high degree of artifice in their apparently artless method. As in the more flamboyant Birdman, their long takes catch every reaction and gesture with great precision.

We always see what we need to see at just the right moment. When something is suppressed–here, the result of a violent knife attack–it’s not an accident (as if the camera were in the wrong spot) but rather the result of our attachment to Ahmed and a clever narrative ellipsis. We could have had a cut like the one in the school, but we remain with Ahmed, and in fact know a bit less than he does about the result of the violence.

All of which is not to deny the originality of Young Ahmed. All the Dardennes films seem modest, but they are, within their limits, quite ambitious in using dramatic psychology to probe social problems. Throughout, I think, we are asked to reflect on how firmly Ahmed believes in his version of Islam. Is it a transitory teen obsession or is he on his way to becoming a dogmatic martyr? We watch his behavior, his encounters with farm life and a young girl, for any signs that his lonely, taciturn demeanor will crack. In other words, this is a suspense film–one based less on the threat of violence (which is there, to be sure) than on how a boy who hasn’t fully formed his character will define himself.

Not such light housekeeping

Both The Realm and Young Ahmed are, to varying degrees, objective in their presentation. We must judge characters by what they do and say. Something very different is going on in Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse. It too adheres largely to one character, but a battery of cinematic techniques, including camera ubiquity, works to plunge us into the man’s mind.

Although the film is a two-hander, it doesn’t balance viewpoints. Thomas Wake, an experienced lighthouse supervisor, arrives at his post with the novice Ephraim Winslow. Almost immediately we are attached to Winslow, who’s assigned grimy menial duties while Wake tends the beacon. Wake tells Winslow that his previous assistant went mad from the weeks of isolation, and very quickly Winslow struggles against the bleak, craggy island they’re on.

We’re prepared for an assault on your senses by the opening, when a ship roars out of the fog toward us. Thereafter, Wake subjects Winslow to a punishing routine of cleaning the cistern, heaving coal into the boiler, and scrubbing floors, while nightly meals with the nattering old salt are just as hard to bear. Winslow’s misery is rendered in vivid, expressionist terms. The deafening fog horns, thunderclaps, and boiler blasts are reinforced by stark, ominous black-and-white imagery. (The film was shot on 35mm film.) Winslow seems trapped in a world of raging elements and gigantic machines.

Eggers builds our affinity with Winslow through classic techniques. He watches Wake at the beacon from a distance; we get optical point-of-view shots of discoveries (real? imagined?) that start to unhinge him.

All the drudgery and pain, punctuated by Wake’s continual harangues and farts, lead Winslow into fantasies and hallucinations. His deterioration is rendered in shock cuts and distended compositions reminiscent of Welles’ Mr. Arkadin or German’s Hard to Be a God. Some will compare the film’s over-the-top climax to that of Aronofsky’s Mother!, but The Lighthouse, with its rapid montage and Gothic chiaroscuro, harks back to silent cinema. The fact that it’s shot in the 1:1.17 ratio favored by early sound film gives it an archaic feel as well. The dialogue, a late title informs us, is drawn from nineteenth-century sources, including Melville and Sarah Orne Jewett.

The Lighthouse has a cadence typical of modern horror films, but Kristin points out that it’s an expressionistic Kammerspiel too–a subjectively tinted drama setting very few characters in a constrained locale. Eggers shows that you can renew a genre’s appeals by reviving imagery from a classic period of film history. When you do it, you’ll still have to make fundamental choices about viewpoint and camera placement. They come with the territory.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis and Shelly Kraicer for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on classic Kammerspiel films go here and here.

The Lighthouse (2019).

More from VIFF 2016

The Death of Louis XIV (Albert Serra, 2016).

The Vancouver International Film Festival ended yesterday, but the films and the pleasures they yielded linger on. Our first two entries are by Kristin, the last two by David.

Smog over Tehran

Iranian film and television director Behnam Behzadi is not well-known outside his native country. Inversion, which was shown in the Un Certain Regard section of Cannes this year, suggests that he deserves to have more international exposure for his work.

The title refers to the meteorological phenomenon that can cause dense pollution to form at ground level. The film opens with shots of Tehran streets seen dimly through a thick haze. The pollution has a causal role to play, since the heroine’s elderly mother ends up in a hospital as a result of breathing problems. More metaphorically, however, the title refers to a sudden reversal in Niloofar’s situation.

Initially she seems to be in a relatively strong position for a Iranian woman. Still unmarried in her 30s, she runs a small, prosperous garments factory and begins to date an amiable man whom she clearly likes. Her mother’s sudden health crisis, however, leads a doctor to insist that she be moved to the healthier northern part of the country, where Niloofar’s sister and brother-in-law happen to own a small villa. Niloofar, with no spouse or children, is pushed by the couple and her brother into agreeing to go along and take care of her mother. She hopes to keep the factory going, but the brother selfishly rents out the premises to pay off his own debts. Niloofar resists going with her mother, but as her siblings ignore her wishes and she discovers that the man she may be considering marrying has kept an unpleasant secret from her, she realizes how little power she has over her own life.

As in Farhadi’s films, a seemingly ordinary situation suddenly deteriorates from a simple cause. But Farhadi tends to gain complexity by avoiding making his characters into villains. In his films, as in Renoir’s, “everyone has his reasons.” In Inversion, however, the brother is straightforwardly in the wrong, refusing to consider Niloofar’s desires and even threatening her with violence during one argument. Overall the film is entertaining, with Niloofar an engaging figure who gives an insight into the situation of women in contemporary Iran.

Mistakes were made

Asghar Farhadi is best known for A Separation (2011), the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film. His earlier masterpieces, About Elly (2009) and my own favorite, Fireworks Wednesday (2006), are slowly coming to be known in the West, largely via home video. After the slightly disappointing The Past (2013), Farhadi is back on track with The Salesman.

The film opens with a tense, dramatic scene in which a Tehran apartment building threatens to collapse and its inhabitants frantically struggle to evacuate. The result is that the central characters, Emad and his wife Rana, must quickly find a temporary apartment (see bottom) while they also prepare to star in a production of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman.

They seem to be coping until Rana mistakenly opens the door of their new apartment, assuming that her husband has come home. The shot holds on the door, standing ajar, as Rana moves off to take a shower and the scene ends. Later we learn that an unknown assailant has entered the apartment. Whether he raped Rana or simply startled her so that she fell and cut herself on broken glass is never revealed, but she is traumatized and unable to proceed, either with her everyday life or her role as Linda Loman in the play. Emad tries to be supportive, but he becomes obsessed with tracking down the intruder.

The mystery gradually unravels as the shady background of the apartment’s former tenant emerges, and revelation of the identity of the intruder undermines the question of revenge. As in Farhadi’s other films, characters’ mistakes, honest or otherwise, compound each other. Ultimately, absolute blame is hard to assign.

The Salesman won two prizes at Cannes: best screenplay for Farhadi and best actor for Shahab Hosseini as Emad. Amazon Studios and Cohen Media will release it in the US on 9 December.

The King is (nearly) dead

Early on in Roberto Rossellini’s Taking of Power by Louis XIV (1966), we find Cardinal Mazarin on his deathbed. Mazarin’s doctors decide to bleed him; a priest advises him on the disposal of his wealth; finance minister Colbert briefs him on intrigues at the king’s court. The shots are lengthy, following the men around the chamber.

This remarkably deliberate sequence was considered quite striking at the time. In a story centered on Louis XIV, Rossellini devotes thirteen minutes to Mazarin. His impending death creates exposition about the ensuing power struggles and initiates a somber pace rather different from that of the standard historical film. The scene also reminds us that historical events have a tangibly material side, as when doctors confer gravely over the stools in His Eminence’s chamber pot.

Rossellini, who’s interested in the tactics by which Louis tames the nobility, doesn’t show us the King’s final hours. That morbid task is taken up by Albert Serra’s The Death of Louis XIV. Unlike Rossellini’s film, which is filmed in radiant high-key and shows sumptuous detail of fabrics and flooring, Serra’s treatment relies on chiaroscuro, with shadow areas broken by trembling candlelight. And while Rossellini’s PanCinor lens swivels and zooms around these apartments, Serra cuts among close views of faces, hands, and a steadily blackening gangrenous royal foot.

In the process Serra expands the physicality of the Mazarin sequence to the length of an entire film. Louis seems to linger for days, but we’re given no distinct sense of how much time passes; in only two shots do we glimpse the outdoors, in bleary light that might be dawn, drab afternoon, or dusk. The time is filled out by court rituals, such as the King’s doffing his hat to his entourage, and by the steady decline of his powers. He can’t swallow food and can barely take water or wine. Through it all, Louis feebly issues his final orders about matters of state and the disposition of his body. A long scene of the last rites is punctuated by a barely discernible fart. This is a movie centrally about a degenerating body.

Even more than Rossellini did, Serra probes the shaky state of medical science of the time. (Louis died in 1715, just as the Enlightenment was beginning.) When Louis’s leg contracts gangrene, the learned doctors debate whether to amputate it. A quack shows up with an elixir made of bull sperm and other recherché ingredients. At the end, the principal physician takes the blame for the king’s death and makes a remarkable apology directly to the camera. Before that, though, Serra has given us a three-minute shot of His Highness reproachfully staring at us (up top) while we hear a Kyrie Eleison somewhere offscreen. Another echo of film history: Louis is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, who looked out apprehensively at us many years ago, in the seashore ending of The 400 Blows. It’s glib to say that cinema films death at work, but here the cliché gains some meaning.

Master of the weepie

Is any filmmaker more unfairly taken for granted than Pedro Almodóvar? For over thirty years, he has created sparkling, handsome entertainments that combine cinematic intelligence with outrageous eroticism and insidious emotional punch. His films revel in plot complications and edgy humor. Along the way he effortlessly deploys the techniques that make modern cinema modern, from flashbacks and voice-overs to subjective sequences and abrupt replays that fill in gaps.

He makes it all look easy, and gorgeous. After the drab grays and browns of Hollywood fare, what a pleasure to see a film packed with saturated primaries and bold designs. He proves that you can go as dark as you like in plotting and still make things look delightful.

His characters are clothes horses, I grant you, but not the least of his debts to Old Hollywood is the belief that we want to see presentable people in pretty costumes and settings. The world is ugly enough, he seems to say; why add to it? Seeing The Girl on the Train reminded me how glum American movies are determined to look. An Almodóvar apple looks good enough to eat, and a housekeeper’s roseate apron seems the height of chic. In this world, even refrigerator magnets evoke a Calder mobile.

These elegantly voluptuous tales make unabashed appeal to Hollywood genres: the screwball comedy (Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, I’m So Excited), the illicit romance (Law of Desire, The Flower of My Secret), the twisty thriller (Live Flesh, The Skin I Live In), even the ghost story (Volver), and above all the melodrama—medical (Talk to Her) and maternal (High Heels, All about My Mother). He rolls Lubitsch, Sirk, and Siodmak into a nifty package, tied up with a ribbon bow of pansexuality.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

Julieta (from which all my images come) revisits the maternal melodrama, specifically the mother-daughter nexus. Our heroine, beginning as a spiky-haired classics teacher, seems to have an idyllic life married to a fisherman, but soon infidelity, misunderstandings, and a tempestuous storm shatter it. All the paraphernalia of melodrama—raging seas, unhappy coincidences, ingratitude, and dark secrets—threaten Julieta’s efforts to save her marriage and protect her daughter. Told in flashbacks, chiefly through a letter she writes her daughter Antia, the two major phases of Julieta’s life get intercut in surprising and gratifying ways. With his usual cleverness, Almódovar has Julieta played by two female performers, with a surprise match-on-action linking them in one scene. A beautiful purple towel helps, as the poster sneakily suggests.

It’s all about guilt, passed from husband to wife and mistress and then to daughter and even daughter’s pal, with the obligatory recriminations and tearful confessions. The plot is continually surprising, yet every scene snicks into place. Neat parallels among couples develop quietly, and tiny hints planted in the beginning pay off. As usual with Almodóvar, the opening credits guarantee that you’re in assured hands. They also tease us with motifs. Here the film’s dual structure (two phases of life, two actresses) is suggested through lemon-yellow letters sliding into alignment.

The two women on my left started crying halfway through the movie. I tell you, this director is a credit to the species.

Special thanks to Michael Barker and Greg Compton of Sony Pictures Classics. Sony will release Julieta in the US on 21 December.

We have earlier entries on Farhadi’s About Elly, on A Separation, and on The Past. We discuss Serra’s ingratiating Birdsong here, and Almodóvar’s cunning The Skin I Live In here.

The Salesman.