Archive for the 'National cinemas: Taiwan' Category

News from Hou

Hou Hsiao-hsien and producer and production designer Huang Wen-ying on the set of The Assassin. Photo by James Udden.

DB here:

Stephen Cremin brings good tidings: Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Assassin, a project planned since 1989 and in production for several years, has completed shooting. It’s aimed for Cannes. More details at Film Business Asia.

About a year ago Jim Udden visited Hou on the set and shared his insights with us in this entry.

A new Hou film, especially if it featured swordplay, would make me a very happy man. 2013 was a good year for several top Chinese directors, especially Tsai Ming-liang, Jia Zhang-ke, Johnnie To Kei-fung and Wong Kar-wai. Having a new film from Hou augurs well for the Year of the Horse. And it stars the sultry Shu Qi.

P.S. 19 January 2014: Alas, the Year of the Horse won’t be as auspicious as I’d hoped. Jim Udden tells me, on the basis of a message today from Ms. Huang, that The Assassin will require another year for post-production. But they are likely to show some clips at Cannes, so there’s that. . . . Thanks to Jim and Ms. Huang for the correction and update.

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

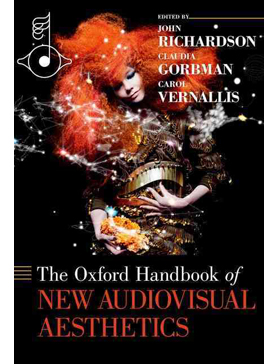

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

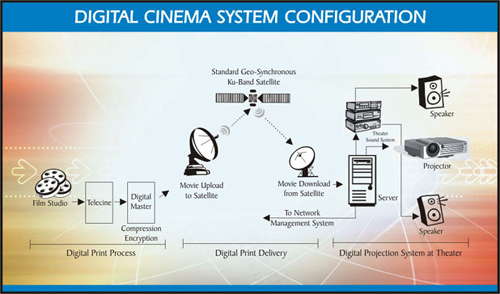

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

Where did the two-shot go? Here.

Our Sunhi (Hong Sangsoo, 2013).

DB here:

I’ve complained here and there about the rudimentary staging of scenes in mainstream American movies. (Short version of common practice: Cut a lot and move the camera instead of moving the actors.) But just as rare as complex staging, in the age of intensified continuity cutting, is the sustained and stable two-shot.

Two actors exchanging lines in a continuous, unmoving take was one building block of mature sound cinema. Today’s directors almost never resort to it. Their face-offs are “given energy” by a drifting or arcing camera, or lots of cuts, or, if they feel like moving the actors around, the Steadicam walk-and-talk.

But the prolonged, balanced two-shot can yield remarkable results. A medium-shot or medium-long-shot framing can work to a human dimension, giving prominence to the actors’ bodies. It doesn’t let their surroundings swamp them, and it doesn’t reduce them merely to faces. It lets the actors act with not just facial expression but with their posture and their upper bodies. And it nicely balances dialogue with the flow of pictorial information. We can watch both actors, with one reacting to the other, as in The Marrying Kind (1951).

Sometimes the two-shot is played with the faces in profile, as in early sound pictures like The Criminal Code (1931).

But directors quickly understood that if you prefer, you can angle the actors so that we get a 3/4 view of one or both. The tactic sacrifices realism (who stands in such ways in real life?) but it’s a piece of artifice we gladly accept. It’s visible in my Marrying Kind example, as well as here in Two Weeks Notice (2002).

Of course two-shots are still with us, but they usually serve to set up passages of shot/ reverse-shot cutting. The sustained two-shot carrying long stretches of dialogue is increasingly rare in Hollywood cinema. It surfaces more often, I think, in indie works (Jarmusch, Linklater, and Hartley, for instance), European films (Garrel, for instance), and perhaps most notably some Asian films.

For reasons not yet well understood, during the 1980s stylistically ambitious directors in Japan, Taiwan, and China began building scenes out of long, static takes. Sometimes those are distant framings, unfolding in elaborate blocking; to my mind Hou Hsiao-hsien is the great master of this. But no less prominent are those films that present simply staged shots of two or more characters in which action and reaction are captured by a fixed camera. Often these shots avoid 3/4 views. That is, we may get two characters in profile, or two characters facing the camera directly. The result is a more abstract, even ceremonial look and feel.

I was remembering this tendency while watching several of the films on display here at the Vancouver International Film Festival. I saw one film very largely made of two-shots. I saw a couple in which the two-shots serve mostly as points of punctuation, breathing space between scenes that are cut up in more orthodox ways. And I saw one film that climaxed in a two-shot showing the actors holding their ground for about fourteen minutes. All were from Asia.

Both visual and plot-based information follows; in other words, as often happens hereabouts, there are spoilers.

The Return of Kids Return

Kids Return: The Reunion, directed by Shimizu Hiroshi, is a sequel to Kitano Takeshi’s 1996 film. The disaffected high-school buddies Shinji and Masaru were last seen riding a bike and declaring that they would show the world what they’ve got. Now, many years later, they haven’t shown much. Masaru is a low-level gangster who has lost the use of his left arm in a jailhouse brawl. Shinji holds a boring job as a security guard, and he’s about to give up boxing. The two meet by accident and resume a more distant version of their friendship. Masaru gets more deeply embroiled in the yakuza world, but he does convince Shinji to stick with prizefighting. As Shinji struggles to improve his skill, Masaru sets out to avenge his betrayed boss, with murderous results.

The new version doesn’t have the dry, laconic quality of Kids Return, and the film doesn’t employ Kitano’s characteristic planimetric framing and compass-point editing. But the incessant over-the-shoulder framings of most movies are avoided; when we cut to a character, he or she is usually isolated in the frame. And some moments recall the cartoon-panel cutting of Kitano. One scene shifts from the yakuza boss, Masaru, and the thug Yuji in a coffee shop to a soundless shot of their young subordinate at the office simply staring off into space. Cut to the three men strolling back to the office, with Yuji commenting that the kid never keeps the sidewalk clean.

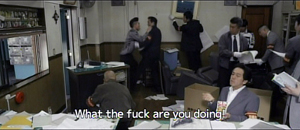

A pan following the men into their building shows the office open and men inside. Yuji bolts past his boss and flings himself at a policeman, who is one of several ransacking the place for evidence.

Most directors wouldn’t include the enigmatic shot of the functionary, but it yields a little question–what is he reacting to?–that the next shots gradually answer.

So cutting plays an important part in building up many scenes. But occasionally Shimizu pauses to draw a moment out. When Murasu and Shinji meet after many years, a nearly thirty-second shot squares them off.

Instead of embracing and pounding each other’s back in the American fashion, they stand awkwardly opposite each other, and the anamorphic widescreen image stresses the tentativeness of their reunion. Later, when Murasu’s boss suggests he leave town and work for another boss, a poised two-shot (at the top of this section) lets us watch the interplay between them across two minutes. Again, the ‘Scope ratio helps, and the fixed frame adds a comic touch by setting at frame center the hideous, ticking clock that Yuji has bought the boss.

I don’t want to suggest that there’s anything particularly radical about Shimizu’s two-shots. Kids Return: The Reunion simply reminds us that a two-shot can usefully vary the film’s pace and lend gravity to moments of character reflection.

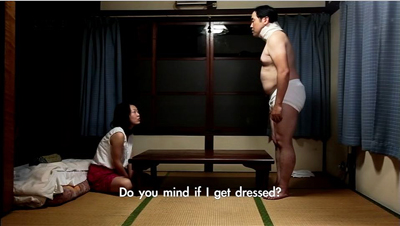

Absurdist anatomy

Something stranger goes on in Anatomy of a Paperclip, the winner of the Dragons and Tigers Award here at VIFF. The story is an exercise in grotesque nonsense, a sort of Japanese Theatre of the Absurd.

In an undefined town outside time (no cars, videos, or cellphones), a harsh boss rules over a crude cottage industry. Three, sometimes four, workers sit along a bench and make paper clips by snipping and twisting wire. The most hapless is Kogure, a lumpish loser wearing a neck brace. Bullied by two outlaws who constantly make him surrender his money and take off his clothes, eating with painstaking regularity in the same cheap restaurant, he returns home every night to sleep. A butterfly visits him and apparently leaves a pupa behind. As Kogure trudges through his days of petty humiliations, the pupa swells to human size, even bigger than the pods in Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Director Ikeda Akira shot the film in fifteen days over weekends and holidays. It’s partly in the planimetric mode, with the camera lined up perpendicular to a back wall or lines in the setting.

Even more than Kids Return, the mug-shot and police-lineup staging recall linear, minimalist manga. A great deal of the film’s feel, that of a frozen, almost robotic world, derives from this deliberately “flat” look.

In Anatomy of a Paperclip, the profiled two-shot functions as part of the overall visual pattern. Although some conversations show 3/4 views of the characters, and even yield occasional OTS (over-the-shoulder) framings, many two-shots preserve the geometrical right angles of the master shots.

Another function of our two-shot, then: To play its part in a film’s overall pictorial design, suggesting expressive qualities like rigidity, automatism, and deadpan humor.

Two’s company, four’s a crowd

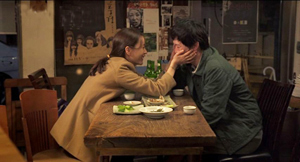

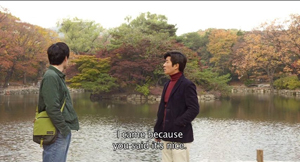

Hong Sangsoo has made the two-shot–usually profiled and showing characters drinking heavily at a restaurant table–into a central formal device. His films are conversation-driven, and he has rung an ingenious series of variations on duologues. They are typically presented in ways that stress similarities and contrasts among characters, often to mildly satiric effect. We see A and B in one setting, then perhaps B and C in another setting, then A and C in the first setting, and so on. For examples, see this entry.

In the more formally complex Hong films, these variants may be played out as intermingled points of view (The Power of Kangwon Province) or as alternative versions of the same events (The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors) or just weird déja-vu (Turning Gate). In an earlier entry, I suggested that Hong exploits our inability to remember certain things precisely, so that we may forget when we first heard a recurring line of dialogue or saw a shot that is echoed by the shot we’re now seeing.

Our Sunhi is about a hugely momentous event that hasn’t, to my knowledge, been dramatized on film before: a professor writing a grad-school recommendation. Sunhi approaches Professor Choi for a reference that will help her study in the States. As she coaxes him into revising his initially cool letter, he becomes attracted to her, as does another university employee Jaehak. Meanwhile Sunhi meets her old lover Munsu, and he becomes attracted to her all over again.

Here the formal rondelay that mocks male vanity–a Hong specialty–doesn’t involve fancy tricks with time or parallel viewpoints.Instead, what circulates are comments about Sunhi, pulled from the professor’s letter (“She has artistic sense,” “She’s honest and brave”) and passed from man to man. The points of circulation come in eleven duologues, each shot in one or two symmetrical long takes. Sunhi meets Jaehak, then Choi, then Jaehak again, then Munsu. Soon Munsu is going out drinking with Jaehak, with whom the prof has coffee before having a rendezvous with Sunhi. Connecting these nodal scenes are brief shots of characters walking through streets, meeting one another by accident, and at the finale, converging in a palace park. As you’d expect, these connecting bits are typically made parallel to each other through framing, situation, music, or other devices.

The two-shots are very long; the longest runs over eleven minutes. It presents a sort of climax, in which a drunken Sunhi reaches out to clutch Jaehak–a gesture of greater intimacy than she has shown any other man.

But soon enough she is meeting the professor for a date in the park. In the very last scene, when she goes off to the toilet, Hong gives us a tiny joke. All three of the men finally meet, waiting for her, and at last a two-shot becomes a three-shot.

This sheerly formal gag is pretty esoteric, I grant you, but it’s typical of Hong’s urge to tweak the simplest materials. In his hands, the lowly two-shot becomes a structuring constraint, a way of deliberately limiting his choices to show us what he can do with it–not least, comic variation.

Two heads, better than one?

During the 1940s, directors in various countries began to rethink the layout of their two-shots. Instead of giving us matching profiled or 3/4 views, they began to arrange their players so that one figure was significantly closer to the camera, yielding what I’ve called a big-foreground composition. In America, the most flamboyant early versions came from Orson Welles (Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons) and William Wyler (The Little Foxes, below). This strategy encouraged staging in depth and even letting players turn their backs to one another.

Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs is the most elliptical and visually variegated film of this VIFF bunch. It’s less a story than a situation: A father, mother, and two children try to survive on the streets. The father picks up odd jobs, while the mother finds work in a supermarket. They wash in public restrooms and scrounge castoff food, sometimes thanks to the mother’s rescuing market goods past their sell-by date. At night, the father and the kids huddle in a makeshift hut, until the mother finds a somewhat better squat in a ruined office building.

Every scene except one consists of a single take, but the connections between scenes are far more oblique than in the other films in this entry. For instance, the mother is seen weeping beside her sleeping children in the opening shot, but then she vanishes from the plot for a while before reappearing in the supermarket, now with her hair cut shorter. The clear and continuous duration of the scenes is offset by a narrative organization that skips over a lot of time and refuses to explain everything that happens in the interim.

Tsai’s visual strategies are quite diverse. Unlike Hong Sangsoo and others in this trend, he doesn’t always keep his camera within a mid-range zone. A scene’s single take can be a striking extreme long-shot or a tight close-up, often of the father (played by the still remarkably waif-like Lee kang-sheng) eating, drinking, or just reciting a poem.

Stray Dogs makes little use of two-shots, and his “clothesline” layouts aren’t quite as frieze-like as those in Anatomy of a Paper Clip.

He saves his devastating two-shot for what is, in this quiet and melancholy drama, as close as we get to an intimate climax. The image at the top of this section shows the husband and wife, her face looming in the foreground while he stands behind her.

Why is this shot, only three minutes longer than one in Our Sunhi, so fiercely hard to take? Hong Sangsoo fills his restaurant shot with gab and plot development. Tsai’s shot, reminiscent of the big-foreground compositions of Welles and Wyler and many afterward, is almost completely unchanging. Neither husband nor wife speaks for fourteen minutes; the only action we see in most of the shot consists of him occasionally swigging alcohol from the bottles he’s stolen and some tears running down her cheek. And we have no idea of when the shot will end because there’s no obvious trajectory set up for it. Like the fixed close-up of a weeping face that ends Tsai’s Vive l’amour, this shot could go on forever.

About thirteen minutes in, the husband grasps his wife’s shoulders and leans his head wearily against her neck.

In a context scoured of what we normally think of as drama, such tiny movements become major events. The father seems at once apologizing for his drinking and trying for a reconciliation.

Tsai has reserved his two-shot for his climax. Instead of becoming a resource judiciously salted through the film (Kids Return: The Reunion) or a stylized extension of a cartoonish world (Anatomy of a Paper Clip) or a core schema for the film’s visual design (Our Sunhi), the two-shot here, rendered as an aggressive image of faces close to the camera, becomes the marker of a mysterious turning point in two lives.

All the films are very much worth seeing for their own reasons. Treating them together, though, reminded me of the power lurking within one very basic cinematic resource.

Last year I considered long-take shooting and staging techniques in that edition of Dragons and Tigers, with comments on Tsai Ming-liang’s Walker.

Just in case this occurred to you: No, Wes Anderson didn’t invent these techniques. This entry and some others explain.

For more on varieties of staging, see On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, you can visit the supplement to Figures here, and the categories Film Technique: Staging and Tableau Staging.

Stray Dogs.

Master shots: On the set of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s THE ASSASSIN

Hou Hsiao-hsien oversees set details for The Assassin.

DB here:

For many years now, contemporary Chinese cinema has found success with costume action pictures like Red Cliff and Painted Skin: The Resurrection. Even prestige arthouse directors got into the act. Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and Zhang Yimou’s Hero (2002) made the popular wuxia (martial chivalry) film respectable, and now we’re about to see several more examples.

Wong Kar-wai, who already found festival and arthouse recognition with Ashes of Time (1994) is (apparently) finally finishing The Grandmaster, a tale centered on Bruce Lee’s teacher Ip Man. Jia Zhang-ke, whose demanding, slowly-paced films Platform and The World got scant distribution in the US, is making a wuxia. Even more surprising is the fact that Hou Hsiao-hsien, master of the gradually unfolding long take, has turned his attention to martial arts. The Assassin, Hou’s first film in several years, is currently shooting in Taiwan.

James Udden is the author of the most comprehensive and authoritative book on Hou, No Man an Island: The Cinema of Hou Hsiao-hsien. For that project he interviewed Hou many times. Jim’s new project, a historical study of how Taiwanese and Iranian cinema became central to world film culture, compelled him to revisit Hou in December. “Hou’s screenwriter, Chu Tian-wen, informed me that if any interview were to happen before I left, it would have to happen on the set itself — if I did not mind. How could I refuse?” Jim has kindly chronicled his visit in the guest blog below, one mixing information with the unabashed admiration of the true fan.

Hou after Hu

Made in Taiwan: A Touch of Zen (King Hu, 1971).

“The first day of a costume picture always goes like this,” Hou Hsiao-hsien remarked to me. It was Assassin’s first day of shooting in Taiwan. The actors had been on call for make-up since 6:30 am were ready to go by 8:00. Now it was late in the morning and the camera had yet to roll. Slowly some of the actors made their way from the dressing into the open air, lounging around in their Tang-dynasty garb, waiting. Shu Qi, the Taiwanese star who launched her career in Hong Kong and has now gained wide exposure (If You Are the One, Millennium Mambo, The Transporter), is among Hou’s cast, and she walked onto the set briefly to inspect something.

Hou made it sound like he had done all this before. And it’s true that he has been at his best with historical material, not contemporary subject matter. Yet never before has Hou gone this far back into the past. Flowers of Shanghai was set in the late 19th century, but this film is set in the 9th century during the Tang dynasty, generally considered the peak of Chinese civilization.

More striking, The Assassin is a wuxia film. The outstanding figure in this genre’s rich history was King Hu, who revolutionized the wuxia in the 1960s and 1970s. A mainland émigré director who began directing in Hong Kong, Hu shot his best work in Taiwan and is a towering figure in that nation’s film history. He was known for his passionate authenticity in costume and settings, but also for his eccentric editing techniques, sometimes involving shots that last a mere fraction of a second.

Hou seeks authenticity no less fervently than Hu, but in terms of editing, he has been the older director’s polar opposite. A cut is rare in any Hou film. Often the shots last on average well over a minute, with Flowers of Shanghai averaging close to three minutes per shot. A year ago I asked Hou if the wuxia tradition would force him to abandon his signature long take. His answer was typical: “ I won’t know the answer to that until I actually get on the set.”

That’s where my visit came in. Hou and his crew had just returned from shooting scenes in mainland China. Now they were starting to film on the lot of the Central Motion Picture Corporation, the government-sponsored production facility that had given birth to the Taiwanese New Cinema of the 1980s.

Many know Hou’s work best through Café Lumière (2003) and The Flight of the Red Balloon (2008), both of which got fairly wide distribution in the West. However, Hou’s lasting reputation as a master is built largely on two things: the remarkable string of films he made in the 1980s as part of the Taiwanese New Cinema trend, and his later works that delve into the historical past, most of all City of Sadness (1989), The Puppetmaster (1993) and Flowers of Shanghai (1998). In these films, Hou explored the subtleties and complexities of mise-en-scène to an extent almost without parallel save for Kenji Mizoguchi. He also explored historical issues in ways almost without precedent. City of Sadness, in particular, gave a human face to a period of Taiwanese history that had long been kept in darkness.

How, through what concrete production decisions, did Hou achieve his lingering, riveting scenes—solemn long takes capturing the textures and tempos of the past? My 2009 book had to rely on secondary reports and my interviews with Hou and his collaborators. Now for the first time, I could observe firsthand.

Admittedly, during my visit I got only a snapshot of the production process. After a prolonged period of financing and preproduction, The Assassin will be shot over several months in China, Taiwan and Japan. According to Hou’s team, it will not be released until 2014. Still, two days on a set did confirm some things about Hou’s creative process, while also leaving some lingering hints of what this major project will be like.

Meticulous mise-en-scène

Sound designer Tu Tu-chih and director of photography Mark Lee Ping-bin.

In my book on Hou, I argued that only in Taiwan could Hou have had the career he had. This is not merely due to the particular set of historical circumstances and institutional pressures and opportunities. It is also because he was fortunate to find a creative team that has sustained his vision.

Prominent members include Mark Lee Ping-bin, the director of photography, and Tu Tu-chih, the sound designer. For Lee and Tu, shooting on the CMPC lot must have seemed like a homecoming, since both had learned their craft at this same studio in the early 1980s. Since then they have become arguably among the best of their respective fields in Asia, if not the world. Then there’s the remarkable production designer, Huang Wen-ying, who has worked with Hou since 1995 and who also is Hou’s main producer. For her this is clearly a dream project. Seeing this calm, soft-spoken yet efficient crew at work in tandem was unforgettable: they seemed to be working hard and meditating at the same time.

Years ago Hou said in an interview that perhaps he is too meticulous when it comes to mise-en-scène. This clearly has not changed. On the first day the camera was not yet on the set. Overheard snippets of Hou’s extended discussions with Huang Wen-ying, Mark Lee and others, gave the impression initially that he was going to shoot an interior scene one way, then another, only by the end of the evening to lead me to believe it had changed once again. Then on the second day, the first day of actual shooting, I returned in the morning to discover that the scene was covered from yet another angle.

Throughout that morning, that single setup underwent three more metamorphoses. Hou and his colleagues tinkered with the set and props so extensively that they broke for lunch before actually shooting — this despite the actors all being on call since around 6:30 am. Not bounded by the union rules typical on a Hollywood set, Hou at times was directly involved in adjusting several minute details. Hou is as meticulous as ever.

Hou never uses storyboards or shot lists. He does not even write out dialogue beforehand for the actors. His scenes have always grown out of the specifics of a setting—usually real locations that spark his imaginative staging and lighting. His modus operandi is to then respond directly to the atmosphere he finds himself in, no matter how long that takes. Everybody who works for him seems to understand this.

Now he had plenty of atmosphere to inspire him. Since original Tang-dynasty buildings are difficult to come by, two large, full-scale structures were being erected from scratch. These were solid buildings that I suspect will be worth a lot of money someday, and they were so large that the CMPC lot could barely contain them.

In the building that was finished, what struck me was the craftsmanship. From the hardwood floors to the intricate slatted, lattice room dividers, the woodwork in the finished structure was immaculate down to the details. Even the tiniest props, including flowers, were real, and breathtaking. Nearby in the production office was evidence of the exhaustive historical research behind this. Drawings and blueprints were to be found among hundreds of over-sized books on Chinese art and architecture.

Although the intricate sets for Flowers of Shanghai had been made in Taiwan in the later 1990s, Huang Wen-ying hired Vietnamese woodworkers to craft them. She claimed they would give slight “French” flavor to the set, evoking a strain of Chinese architecture particular to a foreign concession. I asked if this was the case this time. She laughed, “No, this time it is all ‘Made in Taiwan.’” I sensed some real pride in that statement, and for good reason.

Here lies the answer why this project has taken so long. Last year in Japan, Hou told me that some constraints were financial. The budget, currently reported at between US$12 and 14.5 million, had to be raised from various sources. Above all, though, it took time for Hou’s team to master all of the period details of the Tang dynasty. When it comes to mise-en-scène, no stone is left unturned. In fact, just about every stone, and everything else, is at some point toyed with by Hou himself.

Brushwork, not ballpoint

Crew and Hou with producer and production designer Huang Wen-ying.

Lighting is often the most time-consuming aspect of a film shoot, and you’d expect it to be particularly prolonged on a Hou project. Anyone who has seen either The Puppetmaster or Flowers of Shanghai on the big screen knows the supple gradations of light and shadows typical of a Hou shot. Yet back in 2005, Huang Wen-ying told me that Mark Lee works rather quickly to set up his lighting schemes. I found that almost incredible. Now I know it’s true.

Of all the changes that occurred on the first morning of actual shooting I saw, very few involved the lighting. The illumination was pretty much all set up by the time I arrived around 8:30. Over the course of the morning, only one lighting instrument was added, another was adjusted slightly, and a flag was added to one side.

For the most part Lee had to consult the continuity person about all the subtle changes occurring on the set. Over the course of the morning, Hou and crew dramatically changed the backgrounds of the shot. They hung a new gossamer cloth, added a folding screen revamped with gold leaf, and hoisted a leafless tree that would be visible in the distance. In the picture below you can see the second building under construction.

Lee would observe all these changes and would then confer with Hou as to how things would look on camera. At one point Lee was crouched with the continuity person, pointing at some detail for her to examine from a particular angle. She jotted points down in her large notebook.

In all his films for Hou, Lee’s exceptionally low lighting levels and deep, layered shadow areas would give even Gordon Willis a run for his money. Lee’s subtle lighting has always registered magnificently on film. Accordingly, The Assassin is being shot entirely on Kodak stock, even though digital would be somewhat cheaper. “To shoot on digital instead of film stock,” Lee explains, “is like being asked to paint with a ball-point pen instead of a brush.” No digital work will be done until post-production. I suspect that so long as there is some film stock to be found anywhere, at whatever cost, a Hou film will use it.

Back to basics?

Now that Hou has been on the set, what clues do we have to the result? What will a Hou wuxia film look like?

It’s of course too soon to say, but I did see signs that Hou wants to return to basics. Up to 1993 he notoriously executed long takes with little to no camera movement. Since then his camera has become very mobile — perhaps most notably in the endlessly arcing camera of Flowers of Shanghai. But what I saw in the Assassin shoot was a camera set only on a tripod, not a dolly, and placed at a considerable distance. The arrangement didn’t permit any movements except perhaps some pans or tilts for reframing.

I venture this guess: this will be a Hou film first, and a wuxia film a distant second. It will likely be a wuxia film unlike any other.

On that second day, I had to bid my goodbye to Hou before he had even started shooting. It should have been disappointing to not actually see Hou say “action” or “cut.” Yet this could not be further from the truth. First, I did get my interview late on the first day, fittingly on the CMPC lot. Second, I saw and heard much more than I could have ever expected. When I left America for Taipei, the prospect of being on Hou’s set was the furthest thing from my mind. I came home feeling like the luckiest guy in the world.

More background on Hou’s Assassin project can be found at Film Business Asia and Screen Daily. I discuss principles of Hou’s staging in Chapter 5 of Figures Traced in Light and on this site, in a supplementary essay on his early work and in this blog entry.

Our previous guest post was Tim Smith’s perennially popular “Watching you watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.”

Hou Hsiao-hsien, James Udden, and Hou’s screenwriter and long-time collaborator Chu Tian-wen; Japan, 2011.

P. S. 7 January 2013: Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster made its censorship deadline and was screened in Beijing. Thanks to Ray Pride and Movie City News curated headlines for the link.

P. P. S. 8 January 2013: James Marsh has a rapturous early review of The Grandmaster at twitchfilm.

P. P. S. 8 January 2013, later: Maggie Lee provides an equally enthralled review in Variety.

P.P.P.S. 16 January 2014: Shooting on The Assassin is said to be wrapped. See Stephen Cremin at Film Business Asia.