Archive for the 'National cinemas: Taiwan' Category

Good and good for you

Late Autumn (Ozu Yasujiro, 1960).

DB here:

Manohla Dargis of the New York Times has just written a piece that refers to some ideas that have appeared on this site. If you see the article online, you’ll find the links to appropriate entries, but if you’ve come here after reading the paper edition of the Times, you can find the Tim Smith essay she cites here. It is a remarkable piece of work, and it’s gratifying that Dargis has called attention to it. (Tim’s video experiments have received many hundreds of thousands of downloads already.) My table-setting entry, on task-driven looking, is here.

The backstory is simple. On this site in 2008, I took a slow, unemphatic scene from There Will Be Blood as an example of how a director can subtly guide our attention without cutting, camera movement, or auditory underlining. My analysis was guided by recognition of my own responses and some knowledge of traditions of cinematic staging. Tim, in his turn, used the tools of modern perceptual research to show that we can gain firmer knowledge of directorial craft. By tracking viewers’ eye-scanning, Tim demonstrates vividly that filmmakers can shape our experience of the action on a second-by-second basis. This not only helps us understand how we grasp images. It shows that humanistic inquiry and psychological research can collaborate.

Why so unserious?

Late Spring (Ozu Yasujiro, 1949).

Those who navigate Internet eddies and flows know that dozens of responses have swirled around Dan Kois’ “Eating Your Cultural Vegetables.” Kois wants to like long, slow movies, but after trying for years, he has found that he just can’t enjoy many of them. He can mimic, even anticipate, the judgments of those who do, but in his heart he finds most of the celebrated films boring. He’s now decided to give in to his impulse and declare that he needn’t pretend to enjoy Tarkovsky or Hou Hsiao-hsien:

As I get older, I find I’m suffering from a kind of culture fatigue and have less interest in eating my cultural vegetables, no matter how good they may be for me.

As one man’s confession of guilt and fatigue, this is doubtless sincere, although its sideswiping putdowns of viewers who praise such movies suggest more calculation than humility. Still, this cry from the heart has broader implications, as many Net writers have discussed. Kois’ complaint elicited not one but two responses from the New York Times film critics A. O. Scott and Manohla Dargis. For one thing, Kois’ essay seems to offer aid and comfort to people who are afraid to try something different. Indeed, it lets them feel superior to the phonies who claim to like such films. Moreover, Kois justifies the most superficial response a moviegoer can make. Simply shrugging off a film by saying, “It’s boring!” is about as uninformative a response as saying, “It’s interesting!” And one should always be suspicious of somebody, in the name of debunkery, telling us that we shouldn’t bother to know something.

Kois’ piece exploits the special status that film enjoys in today’s culture. High and low mingle. Because movies are so accessible, and Hollywood movies are so eager to give us what somebody has decided that we want, coterie tastes are dismissed as snobbism. Things seem different in other arts. Would the Times publish a piece in which someone confessed to finding Tarkovsky’s contemporary, the Soviet composer Sofia Gubaidulina, boring? No, because to talk about her is already to enter a restricted and high-level conversation. It goes without saying that a great many listeners would be bored by her music, but who cares what non-experts think about a modern composer? Film, however, is a free-fire zone; anybody’s opinion is worth a public hearing.

I’ve kept out of the fracas because I thought Kois’ piece was silly-season fluff. Of course I wrote my own replies in my head, such as We used to have a name for this: Philistinism. I also thought that the essay operated in bad faith. Kois wasn’t as apologetic as he tried to seem. He claims humility (he “yearns…to experience culture at a more elevated level”) when really disdaining this area of cinema and considering the people who claim to enjoy it mere poseurs. The exaggerations show, I think, that this is not a serious piece:

Surely there are die-hard Hou Hsiao-hsien fans out there who grit their teeth every time a new Pixar movie comes out.

Surely not.

Still, Kois’ complaint touches on something important about film history. We have a polarized film culture: fast, aggressive cinema for the mass market and slow, more austere cinema for festivals and arthouses. That’s not to say that every foreign film is the seven-and-a-half hour Sátántangó, only that demanding works like Tarr’s find their homes in museums, cinematheques, and other specialized venues. Interestingly for Kois’ case, many of the most valuable movies in this vein don’t get any commercial distribution. The major works of Hou, Tarr, and others didn’t play the US theatre market. Sátántangó is just coming out on DVD here, nearly twenty years after its original appearance. Most of us can’t get access to the most vitamin-rich cultural vegetables, and they’re in no danger of overrunning our diet.

The race is to the slowest

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989).

For the historian, the polarization between fast pop movies and slow festival films asks to be explained. My take goes roughly this way.

From the 1940s through the 1960s, certain directors developed a new approach to telling stories. Antonioni, Dreyer, Bergman, and a few others opted for a style that relied on slower pacing and even “dead moments” that seemed to halt the narrative altogether. “Dedramatization,” it was sometimes called, and many rightly considered it a powerful innovation in the history of film as an art. But these films did get a purchase on the international movie market, often for other reasons (sex in Antonioni and Bergman, religiosity in Dreyer). They also came along at a time when there was a niche audience eager to have new cinematic experiences. (On this period see Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens.)

But artists being artists, competition grew up. The long take, for instance, got longer and more virtuosic. Miklós Jancsó, shamefully ignored today, made a series of pageants of Hungarian history in superbly sustained, intricate camera movements; some of his films have only twelve shots. But his films are sumptuous compared to what we found elsewhere. From the late 1960s through the 1970s, it seems, a new generation of filmmakers competed to make ever more austere films. They often kept the camera fixed, framed the action at a distance, and sustained the shot for many minutes. The works of Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet are the high-water marks of this trend, but there were also Chantal Akerman, Theo Angelopoulos, and even Rainer Werner Fassbinder (Katzelmacher) and Wim Wenders (Kings of the Road). Werner Herzog’s successful career as a documentarist has perhaps let people forget that he once made very slow and demanding films like Fata Morgana; his Heart of Glass, screened in US arthouses in the 1970s, would surely not find a distributor today.

From a marketing standpoint, the avant-garde overplayed its hand. The new austerity came along just when Spielberg and Lucas were reinventing Hollywood. As movies got faster and louder, long-take minimalism looked perversely ascetic. Some of the directors, like Straub and Huillet, remained loyal to their project; others crossed over. It is quite a shift from Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), a 201-minute film mostly about housework, to the musical The Golden Eighties (1986) and A Couch in New York (1996). Likewise with Wenders’ Summer in the City (1970) and Wings of Desire (1987). I happen to admire both strains in these directors’ works, but there’s no doubt which is the more audience-friendly.

Today, directors who persist in long-take, slowly-paced storytelling are aiming chiefly at the festival market, which means that most of their films will be shown theatrically only, to be blunt, in France. But some of the greatest directors of our time, notably Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, and Abbas Kiarostami, have done their best work in this mode. The US arthouse market has taken decades to discover them, through more accessible works like Flight of the Red Balloon, Yi Yi, and Certified Copy. Kois confesses to loving Yi Yi, so I’d urge him to look at Yang’s Terrorizers and A Brighter Summer Day, more rigorous but no less gripping films, though they lack the traditional arthouse bait of a charming child. Hou’s Red Balloon also has a cute kid and refers back to an arthouse classic, while Kiarostami, not normally given to couples and romances, offers us in Certified Copy a pleasantly teasing take on Antonioni and Resnais.

Minimalism of the 1970s variety got revived by 1980s American indies, notably Jim Jarmusch, but with more entertainment value. In later years he too crossed over stylistically; however unpredictable the plot maneuvers of Ghost Dog and Broken Flowers, they lack the long takes and open-ended unfolding of time we find in Stranger than Paradise. Even Kelly Reichardt, one of Kois’ targets, doesn’t give us anything like the severity of the 1970s generation. That makes the “purer” films from overseas that persist in this tradition even more off-putting. If Kois can’t take Meek’s Cutoff, as he claims, he’d find Hong Sangsoo (Oki’s Movie) or Liu Jiayin (Oxhide and Oxhide II) cinematic chloroform.

So Kois may assume that “boring” films have persisted in today’s film culture because of snobbism, but there are deeper reasons. The competition among filmmakers to push an aesthetic horizon further, the narrowing of audience tastes, the search for a budget-appropriate niche that could stand in opposition to the visual spectacle of the New Hollywood–these seem to me important factors in making slow movies a ghetto for cinephiles.

Why shouldn’t people follow Kois in giving up their vegetables? No reason, except that they’re missing some worthwhile cinematic experiences. Not all austere movies are good, but viewers who want to expand their cinematic horizons should consider the possibility of learning to look at certain movies differently. Kois can’t see that; he thinks that people who like the movies that bore him are usually phonies. But I believe that some of those admirers have developed a repertory of viewing habits that adjust to different cinematic traditions. If you can like both Stravinsky and rock and roll, why can’t you like Hou and Spielberg?

Look again, closer

Voyage to Cythera (Theo Angelopoulos, 1984).

This is the prospect opened up by Dargis’ latest article. She suggests that Kois’ response isn’t wholly based on taste. It may stem from literally not knowing how to look at certain kinds of movies.

Kois’ article treats most defenses of slow films as a matter of hand-waving and you-see-it-or-you-don’t attitudinizing. Again, he has a point: Those reactions are common, I think. The fact that cinephiles must face is that this sort of film is very difficult to talk about. We can point out the creative choices in Hollywood because narrative in some degree drives everything we see and hear. But when narrative relaxes, most viewers don’t know what to look or listen for.

The problem has haunted me for decades, ever since the 1970s when I took an interest in Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, and Mizoguchi–all filmmakers felt, at the time, to be slow. I failed to come to grips with the problem in my 1981 book on Dreyer; I even anticipated Kois in calling Gertrud (another item that would never grace theatre screens today) boring–but I took that to be a good thing, as a challenge to conventional viewing habits.

What can I say? I was young. Since then, I think I’ve come up with better ways of talking about the other directors I mentioned, as well as some in their camp, such as Angelopoulos and Hou and Tarr. A lot of my answer comes down to the way, pace Dargis and Smith, they structure our attention.

My arguments are set out in the places I mention in the tailpiece of this entry. In brief, these filmmakers become engaging, even entertaining, when we realize that they are to some extent shifting our involvement from characters and situations to the manner of presentation. Not narrative but narration is what engages us. And we need, as Dargis points out, some schemas for grasping these alternative patterns. We have robust and refined schemas for following a story, but grasping the dynamics of narration, the how as well as the what, takes more practice, and perhaps some instruction from critics.

The process is like taking in an opera on two levels: following the stage action but also registering the patterns, the emotional highs and lows, of the music that accompanies–and sometimes overwhelms–it. Let Papagena and Papageno stammer each one’s name again and again. The repetition isn’t needed for the drama, but it’s thrilling on sheerly musical grounds.

Now imagine that sort of development transposed to cinema, in which we can appreciate, at one and the same time, not only the story’s unfolding but the patterns that present it. The supreme master of this possibility, I think, is Ozu, perhaps cinema’s Mozart. But you can find the same qualities in more somber key elsewhere. For example, in watching Angelpoulos’ Voyage to Cythera, I think that you have to be prepared to see the arrival of track workers in yellow slickers, visible through the speckled window pane in the shot above, as a kind of visual epiphany, the quiet equivalent of a stunt in a summer tentpole picture.

Given a narrative mandate, we’re on the lookout for pictorial factors that affect the dramatic situation. But when narrative slows, other things, maybe not of narrative moment, pop out, like the yellow-garbed train workers on their handcar. At such moments, it’s not that our eyes roam around aimlessly; it’s that the director guides us in a different way, toward a visual search that isn’t wholly driven by plot considerations. Here’s a shot from Ozu’s End of Summer (1961).

The principal action is a party of young people singing. But the faces are no more important than the gleaming drinks on the table, a little suite of colors and shapes that become fascinating in themselves. (For instance, several of the liquids and bottle labels sit along the same horizon line, regardless of how far the drinks are from us.) You don’t discover this half-gag, half-still-life by groping: Ozu has lit it and composed it so that you’re invited to discover it. He has found a way to activate what in most movies would be filler material. And if you think that noticing colors and shapes on the tabletop is just trivial, consider that we enjoy staring at the same sorts of patterns in an abstract Kandinsky. Or is he cultural roughage too?

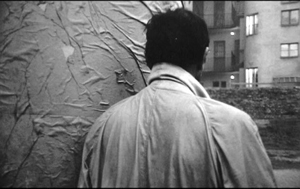

In an Ozu film, even though he cuts rather fast, we’re given time to see everything. But this isn’t random rummaging. It’s visual exploration guided by Ozu’s decisions about composition, lighting, and color. Something similar, I think, is going on with Tarr, although there it’s more a matter of texture and tactile qualities. His people shamble through mud, oily puddles, dusty corners, and tearing winds. In one shot of Damnation, a rain-soaked wall shrivels to match a wrinkled topcoat.

The story is still going forward, but by turning his protagonist from us and aligning him with the wall, Tarr has given his shot an extra layer of sensuous appeal. Try to remember the way any wall looked in Transformers 3, before it got blasted to rubble.

Slow movies let us look around, and good slow-movie makers give us something to see when we do. But what do we do when these accessory appeals don’t just accompany the narrative but swamp it? What if we lose track of the characters? The film may steer us to pictorial or auditory qualities that take over our perception.

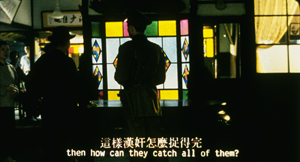

The authorities are looking for a man in the family in Hou’s City of Sadness, but you have to rely almost solely on dialogue to identify what’s going on and who’s speaking.

The sheer pictorial beauty of the shot becomes a sort of anti-narrative pretext. But if you’re alert, you won’t take the plot off the table, because at one crucial moment a figure flashes through the far left background, more or less fully lit, who may be the suspect the cops are seeking.

Sometimes you have to destroy narrative in order to save it.

Hou asks that we engage with his distant, fixed images in a complex way, being patient but vigilant, enjoying abstract geometry while also sustaining old-fashioned suspense. It’s this dynamic between story and style, fastening on plot elements but also discovering accessory pleasures and patterns, that I think constitutes one delight of the sort of films that Kois finds boring.

Add Bresson, Mizoguchi, Dreyer, Tarkovsky, and others to my list of directors whose very different styles invite us to explore what the rapid pace of most narrative cinema refuses to dwell upon. These filmmakers invite us to grasp the space and time of a scene in a fresh way. The details and dimensions of a world surge forward, not simply as a backdrop for characters hurtling toward a goal, but as something valuable in their own right. For some viewers, me included, they do more. They also ask you to transfer those viewing skills to life outside the theatre. They encourage you to find a new way to look at our world.

Not all slow, minimalist movies are good. That’s why I think critics are obliged to rebut Kois with careful analysis, not the gaseous generalities about sublimity and eternal mystery to which we too often resort. Digging deeper, we can not only answer skeptics but expand our understanding of how cinema works. These films have opened windows for many of us. Why should we keep them to ourselves?

First, thanks to Manohla Dargis for enjoyable correspondence about these issues.

Tim Smith’s blog, Continuity Boy, is a good way to keep up with his energetic and expanding research program.

Dargis mentions the invisible gorilla experiments of Chabris and Simons. I talk about their relevance to film here and here.

Kristin has written on comparable matters in Tati; she even wrote an essay on M. Hulot’s Holiday called “Boredom on the Beach.” (It and an essay on Play Time are in her book Breaking the Glass Armor.) Tati’s films, in their spasmodic pauses and shamelessly repeated or sustained gags, could also count as part of the postwar dedramatization trend.

My initial arguments about different registers of viewer perception and cognition were made in Narration in the Fiction Film (1985). My case for Ozu is in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available online. More recently, I’ve become interested in cinematic staging and have concentrated on challenging directors like Mizoguchi, Angelopoulos, and Hou; see On the History of Film Style (1998) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). All of these “slow” filmmakers ask us to be sensitive to unusual sorts of narrative patterning, and some purely non-narrative patterning. More thoughts on these matters can be found in The Way Hollywood Tells It (20006) and Poetics of Cinema (20007).

On this site, you can find similar lines of argument, especially about Béla Tarr, Mizoguchi Kenji, and silent directors like Louis Feuillade, Victor Sjöström and some Danish creators. See director entries for Hong Sangsoo, Liu Jiayin, and others mentioned above. Later this month I hope to post a bit more about how directors guide our attention without recourse to fast-paced editing–before editing was really invented.

Sátántangó (Béla Tarr, 1994).

Dragons, tigers, one bear

Sawako Decides.

DB here:

As has become our habit, we’re at the Vancouver International Film Festival, gulping down movies. The perennial Dragons and Tigers collection of recent Asian film is especially ripe this year, at over forty-three features and many shorts, and of course there are several other choices, across ten venues, competing for your eyeballs. Herewith, my first dispatch from this sunny, hospitable city. Kristin will follow up soon.

A girl, a boy, and many guns

She’s completely ordinary, “below-middle,” as she proclaims. Her contribution to a conversation is always a couple of steps behind. She spends her nights watching TV and guzzling beer. She has lost five jobs and been dumped by five boyfriends. Her main relaxation seems to be colonic irrigation. But when she’s fired and her father lies dying, she returns to her hometown to take over his clam-processing factory. She brings in tow her latest paramour, a twitchy ex-toy-designer who enjoys knitting.

Such is Sawako, who has the face of an anime princess and the mind of . . . well, that’s part of the problem. Psychologically, she’s the opposite of those fast-comeback youngsters spraying American indies with quirk. She mopes in her father’s factory, absently minds her boyfriend’s daughter, shrugs off the malice of her former teen friend, and ignores gossip about why she left town in the first place. Nothing can shake her obdurate passivity. She won’t fight. With beer as her only solace, Sawako seems not the stuff of drama at all.

But drama, tradition tells us, pivots on decisions (usually bad ones). Sawako Decides surrounds a woman resigned to misfortune with a range of eccentrics who do take action, sometimes recklessly. There are the older women who work in the processing plant, the faithless boyfriend with his powder-blue sweaters, the vindictive ex-friend, the alcoholic father who rips off his IV for a fight, even a college girl doing research on toxic clams. When Sawako finally chooses to do something, she’s acting, she says, for all the “below-middle” people—that is, nearly all of us. Associated throughout with body wastes, she turns the tide: Even the feces she spreads on the family garden yield a giant watermelon. The film ends with a trim long take in which Sawako finally blows her top and finds an agreeably aggressive use for her father’s bones. Ishii Yuya’s film shows how the blankest of characters can, if treated with wary respect, yield engaging cinema.

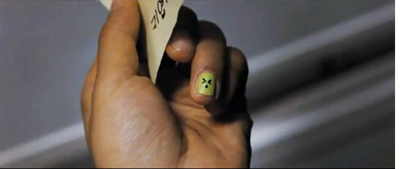

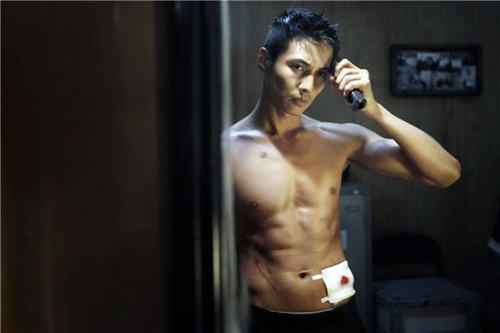

Won Bin is probably best known to Western audiences as the scatty, tormented son in Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, but he’s become a major Korean heartthrob. I know this because of the collective gasps and shrieks that greeted moments of The Man from Nowhere, a grisly action picture by Lee Jeong-Beom. Won plays a retired government agent running a pawnshop in a seedy neighborhood. He reenters the underworld to rescue a neighbor woman’s daughter, snatched by a drug gang for a little child labor and organ-stripping. He is a Bourne-style killing machine, and he is given plenty of chance for some rousing brawls and gunplay (though most of his fighting skills can be credited to editing and blur-o-vision camerawork). Mountainous, bug-eyed, and ominously silent bad guys round out the cast. Director Lee is also shrewd enough to feed the fanbase. There are some touching moments between the girl and the hitman; she even gives him a decorative fingernail while he sleeps. The film’s pin-up image shows Won, stripped to the waist at the mirror, clipping his hair, a bloodied groin-level bandage artfully completing the ensemble. (If you can’t wait, see the end of this entry.) A limited North American release comes later this month.

Excess, two varieties

I’ve written briefly about Sono Sion’s perverse coming-of-age tale Love Exposure, and this year’s Vancouver fest brings us his latest, Cold Fish. Who would have thought that business rivalry between two tropical-fish vendors would lead to the carnage we see here? Meek Shamoto has a sexy wife and a disobedient teenage daughter. An aggressively friendly rival, Murata, owns a much bigger shop and offers to take the wayward Mitsuko under his wing. Soon Murata reveals that he plunges as voraciously into murder as he does into fish connoisseurship, and Shamato is caught up in the untidy business of human butchery.

A charnel-house of copulation and dismemberment, the film takes place in a vacuum; a police investigation comes virtually as an afterthought. Cold Fish is more linear and genre-bound than Love Exposure, but when the quiet march of Mahler’s first symphony signals the onset of dread you recall the wilder side of the earlier movie. Also carrying over is the blasphemous use of Christian iconography, associated here with slaughter and child abuse. The film is in the tradition of The Family Game and other dismantlings of Japanese domesticity. Once again, you can find as much lust and murder as you like just by looking into the nuclear family. In this case, the choice offered to the father is straightforward: be a wimp or be a brute. Sono aims to outrage, but once you know that you’re in for a bloodbath, you settle comfortably in for an engrossing exercise in splatter, Japanese-style.

At the other extreme is The Drunkard, Freddy Wong’s adaptation of Liu Yichang’s well-regarded novel about a dissolute writer. Lau wants to be the Hemingway of Hong Kong, but his addiction to alcohol and his inability to love drive him into writing film scripts, pulp fiction, and eventually pornography. The fear of selling out your artistic ideals may not strike a chord in the age of Damien Hirst, but in the 1960s, the novel’s epoch, it held sway over literary culture. Lau’s struggle is presented as an oscillation between his collaboration on a literary magazine and his grubby business dealings with movie producers and publishers. In between, and constantly, he smokes and drinks. The women along his downward path include a seventeen-year-old temptress who has read Lolita, a sincere working woman who offers him lodging and sex, and an aged landlady who thinks he’s her son. His drunken refusal to sympathize with their needs brings sorrow to nearly all and death to a couple of them.

The Drunkard is shot in an unusual style. There are almost no long shots; the framing above is about as far back as the camera gets. Nearly everything happens in medium-shot and close-up. Wong was partly making a virtue of necessity, since streets and shops of the Hong Kong of the 1960s could not be reconstructed on the film’s budget. The positive result is an unrelenting concentration on Lau and repetitive bits of his behavior–gesturing with a cigarette, pouring whisky, or fading into a blackout. From scene to scene, we’re confined to his awareness, broken by fragmentary memories of wartime Japanese invasion. Only after his binges do we learn how viciously he acted when under the influence.

This tightly circumscribed world is enhanced by shots focusing on only a curtain edge or a streaked whisky glass, while people and surroundings drown in a blur. Shot on the Red camera, The Drunkard shows that high-definition digital is perfectly capable of giving foregrounds or backgrounds a hallucinatory softness. That softness, you could argue, is a correlative for the drunkard’s vision, locked on details and oblivious to the flux of human passions around him. In its effort to render the glowing warmth of alcohol, Wong and his cinematographer Henry Chung have given digital cinema a decisively subjective turn.

Two men and a sofa

Ho Wi Ding’s Pinoy Sunday is a heartfelt, low-pressure comedy-drama that makes some telling points about cultural dislocation. Dado and Manuel are Filipino “guest workers” in Taiwan. Friends since high school, they work in a bike factory and live in the factory dormitory. In their dreams they imagine installing a lavish raspberry-bright sofa on the dorm roof where they could lounge, drink beer, and look at the stars. One day, visiting Pinoy on break, they see that very sofa abandoned on the street.

Emigrant Filipino workers fill the lower-rank jobs in many Asian countries, and I’ve seldom seen fiction films show the texture of their lives. Through Dado’s phone conversations with his family, the pain of loss comes through. He buys his daughter a Barbie for her birthday, even while he carries on an affair with an émigré woman (who herself has a husband and family back home). Manuel is on the make, but with winning naivete has a knack for picking the wrong women to idealize (hookers, policewomen). In a way, the sofa becomes the tangible emblem of not just material comfort but the men’s aspiration for a more stable life.

With something of the wistful satire of 1960s Eastern European films like Intimate Lighting or The Fireman’s Ball, Pinoy Sunday turns an anecdote into a mini-saga. (It was inspired by Polanski’s Two Men and a Wardrobe.) At the canonical turning point (circa 28:00), Manuel persuades Dado to carry the sofa back to their dorm before the gates close. The ensuing misadventures recall Laurel and Hardy, but with stronger sentiment.

Their journey reminds them they are outsiders. A TV reporter thinks they’re Malaysian. Trying to explain an accident to a cop puts them at a disadvantage. Their inability to speak Mandarin gives us a crash course in how gestures, English phrases, and situational logic are pieced together to communicate across cultures. At the height of the men’s frustration, there is a poignant musical interlude that evokes magic realism, but that moment is immediately undercut by sober reality. Yet our concern for these two resilient strivers is rewarded with a sort of happy ending.

Finally, the bear of this entry’s title is Alex Law’s Echoes of the Rainbow, the Hong Kong film that won the Crystal Bear at this year’s Berlin festival. I haven’t seen it yet but I hope eventually to pass you some words about it.

The Man from Nowhere.

A masterpiece, and others not to be neglected

About Elly.

DB still in Hong Kong:

I haven’t been slack, honest; I’ve caught several items at the archive and during the first weekend of the Film Festival. I even saw Watchmen, accompanied by rump-shaking Shaw Active Sound. But today let me get caught up with some films I saw in Filmart last week.

I was unimpressed by the picture that launched Filmart, Derek Yee’s Shinjuku Incident. Billed as Jackie Chan’s emergence as a real actor, it features him as a confused illegal immigrant thrown into the Tokyo underworld. His character never made sense to me, and the direction was formulaic: basically pan around a group of actors until somebody says something. Daniel Wu gets to play another maniac.

Less heralded Filmart screenings were much more satisfying. The best, and my favorite film I’ve seen so far this year, was About Elly. It is directed by Asghar Farhadi, and it won the Silver Bear at Berlin. I can’t say much about it without giving a lot away; like many Iranian films, it relies heavily on suspense. That suspense is at once situational (what has happened to this character?) and psychological (what are characters withholding from each other?). Starting somewhat in the key of Eric Rohmer, it moves toward something more anguished, even a little sinister in a Patricia Highsmith vein.

Gripping as sheer storytelling, the plot smoothly raises some unusual moral questions. It touches on masculine honor, on the way a thoughtless laugh can wound someone’s feelings, on the extent to which we try to take charge of others’ fates. I can’t recall another film that so deeply examines the risks of telling lies to spare someone grief. But no more talk: The less you know in advance, the better. About Elly deserves worldwide distribution pronto.

Also worth seeing was A Place of One’s Own, a Taiwanese film that uses imagery of living spaces to explore generational differences. As a young rock singer’s career fades, his pop-star girlfriend’s career takes off. Their fates are intertwined with those of a family who live near a cemetery. The father makes exquisite paper dwellings that are burned during funeral ceremonies, the mother maintains gravesites (and talks to ghosts), while the son launches himself on a real-estate career with the help of a dodgy rich kid. Director Ian Lou (God Man Dog) enhances this network narrative with some clever flashback constructions as well.

My Dear Enemy.

Two films I saw in the market display different ways of using past incidents to explain a story’s present-time crises.

My Dear Enemy, by Lee Yoon-ki, exhibits a striking concentration and dramatic focus. Hee-soo’s boyfriend Cho borrowed $3500 from her before they broke up. Today she has tracked him down and demands it back. She drives him around as he visits various associates—his biker cousin, a high-class prostitute, a rich older woman who seems to be using his sexual services, an unmarried mother—scrounging for money to pay Hee-soo back. Across a day of setbacks both comic and frustrating, we come to learn of their romance and their deeper personalities.

At first Cho seems the classic annoying charming rogue, chattering about the music he likes, pausing to buy flowers and oversweet coffee, flattering every woman he meets, and on the verge of ducking Hee-soo’s demands. Every time he gets out of the car, you think he might bolt. These first impressions, however, get nuanced as we see how he moves easily and even gracefully through his milieu. He seems a loser, but we learn that he is resilient and resourceful. Meanwhile Hee-soo’s righteous determination to get her money back comes to seem something of a desperate effort to close the book on painful episodes from her past.

Lee Yon-ki, who earlier gave us This Charming Girl, is very good at structuring scenes so that we understand every character’s changing attitudes. To get the money, Cho lets his target think that he’s helping out Hee-soo, and at one point he implies that she’s pregnant. As Hee-soo realizes that he’s making her play a part in his drama of self-aggrandizement, she is hurt and ashamed. And Cho’s happy-go-lucky facility in his milieu makes her feel more of an outsider. One scene, in which Cho’s hooker friend calmly insults Hee-soo, is a subtle study in casual humiliation.

Yet Hee-soo’s tenacity wins Cho’s respect. At the same time, while as the day passes into night, Cho emerges as a figure with his own code of honor (he eventually provides a meticulous account of what he’s cost her in the day’s expenses) and even a dream of success that might, the last shot suggests, be fulfilled. Bits of business around coffee, cellphones, flowers, and a broken windshield wiper chart the fluctuations in their relationship concisely. My Dear Enemy is a model of how to make a tight, intimate movie focused on simple incidents that carry almost Hitchcockian tension: Will Cho pay Hee-soo off? Will he slip away and abandon her again? What will we learn next about each one’s past? Like About Elly, this is a character study with an engrossing plot.

More diffuse, I thought, was Ann Hui’s unfortunately titled Night and Fog. It’s a companion piece to The Way We Are, her 2008 study of life in the Tin Shui Wai area of Hong Kong. I offered an admiring account here.

This is the “darker story” Ann promised us at last year’s festival, and it’s based on an actual case. Lee Sum has married a Mainland woman, Ling, and has fathered two daughters with her. He’s on social security and Ling works as a waitress. But Lee is considerably older, and he suspects her of flirting with other men. He becomes insanely jealous, beating her and throwing her and their daughters out. Ling finds happiness in a woman’s shelter, but social services fail her and Lee brutally murders her and the children.

No harm in telling you the ending because the murder is the first thing we see. The film consists of a series of flashbacks, some nested within others, that trace what led up to Lee’s horrendous crime.The plot is presented in the framework of a police investigation, with witnesses to Ling’s life answering questions that pass into scenes from the past. The early flashbacks are quite linear, treating the buildup to Ling’s stay in the shelter and a moment in which she sings a song about a mushroom maiden. Then we plunge further into the past, showing her leaving her provincial home as an adolescent on the way to work in the city. Soon we’re given early moments in Lee’s courtship of her.

One effect of introducing the early stages of their marriage late is to mitigate the harsh portrayal of Lee that has dominated the first half of the film. He seems genuinely in love with Ling, and he rebuilds her parents’ home. Already, however, we glimpse his drunkenness, his sadism, and his aggressive sexual appetites.

On the whole, I’m not sure that this complicated flashback structure serves the film well. At times it is strikingly symmetrical, as when a scene of Lee returning from Shenzhen on the train is followed by a distant flashback of the marriage, and this is closed off by a shot of Ling and her daughters traveling on the same train. At other points, though, the relation between the witness’s testimony and the flashback episodes is arbitrary, with the flashbacks showing scenes unrelated to that witness’s knowledge of the family drama.

It seems to me as well that the power of the events leading up to Lee’s murder of his family is vitiated by the protracted Mainland visits, widening the film’s field of view to life in Sichuan and Ling’s family. Where My Dear Enemy lets its backstory emerge in piecemeal fashion through hinting dialogue, dramatizing every relevant moment in Ling’s past seems to lose some focus.

Likewise, there’s a certain fuzziness about the film’s main thrust. Is it a character study, trying to explain why Lee is violently jealous and why Ling stays with him? The only clear answer I could determine was her sense of indebtedness for his help to her parents. Is Night and Fog then best taken as a critique of the Hong Kong bureaucracy? The social workers are portrayed as indifferent or unable to understand domestic violence. But in that case we need to see more of the mechanisms of decision-making than we do, and then many of the intimate relations of the couple would be extraneous. The battered women’s shelter, while not unblemished, becomes the opposite pole to Ling’s dangerous household, and Huipresents it as a safe space where women can express their feelings spontaneously. But again, this angle on the material seems vitiated by bringing in a public protest against real-estate development of the harbor area—an important issue, but in the context a bit distracting.

The film seems to me to excel in areas that Hong Kong cinema has made its own: extreme emotion and sheer physicality. The violence of Lee’s assaults on his family are terrifying, and Simon Yam’s performance is tremblingly ferocious. Smoking furiously, swigging cans of beer, Yam gives us Lee Sum as a figure on the edge of destruction. He makes even fishing seem an act of aggression. Lee’s incessantly jiggling leg is like the timer on a pressure cooker, and when he sits down with his son from a previous marriage—a sleepy-eyed young pimp—the two of them share the same foot-jiggling tic. In this shot, Hui gives us a diagram of male aggression ready to burst.

If My Dear Enemy trades on suspense, Night and Fog creates dread. One is roundabout, the other more direct; one suggests much, the other shows everything. Two ways, we might say, of making modern cinema.

More, including another Iranian masterpiece, in my next communiqué.

Night and Fog.

Dispatch from sunny Vancouver

Ballast.

After six days, plenty to report from the Vancouver International Film Festival. It has been unusually warm and sunny during our first week, but we have diligently spent most of our time in darkened theaters.

Kristin here:

Another country heard from

It’s a rare day when one gets to see a Haitian film. It’s an equally rare day when one gets to see a Jordanian film. On Monday I saw both, and the contrast between them could hardly have been greater.

Eat, for This Is My Body (Mange, ceci est mon corps, 2007), a Haitian/French co-production is Michelange Quay’s first feature. A Haitian-American, Quay received his MFA in directing at New York University.

The film’s opening is extraordinary, with a series of low-altitude helicopter shots beginning over the ocean and then moving rapidly across huge shanty-towns and finally into bleak mountain canyons in the country’s interior. After this passage of flight over bright landscapes, the bulk of the story takes place in and around a quiet, dark, nearly deserted colonial mansion somewhere in the countryside.

I’ve noticed that there seems to be a mini-revival of 1970s-style art cinema conventions. After many years in which art cinema tended to mean intricate psychological studies, a more challenging, formalist avant-garde seems to surface now and then. While watching Eat, for This Is My Body, it occurred to me that it could almost have been called Haiti Song, so strongly did it remind me of Marguerite Duras’s India Song. There enigmatic actions, often dancing, were staged in a colonial house. Eat, for This Is My Body’s action is, if anything, more enigmatic, though in this case the native population is present in the house in the person of a dignified manservant and a group of nine boys brought at intervals into the house, apparently as a treat.

The story is so minimal as to be non-existent. Apart from the nine boys, there are only three characters: an  old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

old woman, a young woman, and the black servant. Not until about 70 minutes into a 105-minute film are these characters identified, though only to the extent that the younger woman is revealed to be the daughter of “Madame.” There are hints of an erotic attraction between the daughter and the servant, though this comes to nothing. The daughter’s wandering through the local town, among the teaming population engaged in washing, selling, and other everyday activities suggests that she may be gaining some insight into native Haitian culture—but this, too, remains a mere hint. Ultimately, the film creates not a narrative, but an evocative narrative situation full of mystery. The film was shot on 35mm and creates a lovely, austere style for the scenes shot within the mansion.

The Jordanian film, Captain Abu Raed (2007), takes a more familiar approach, centering around a likable, heartwarming protagonist. Raed, an airport janitor, finds an old pilot’s hat, and the children in his working-class neighborhood assume he really is a pilot. He plays along, less to feed his own ego than to inspire their imaginations through false tales of his adventures abroad. Gradually he becomes more involved in the lives of some of his listeners, and the film progresses from the sugar-coated tone of the opening scenes into a darker situation as Raed seeks a way to save the family of a violent neighbor.

Director Amin Matalqa was raised principally in the U.S., but he returned to his native country for this, his first feature. It is also the first feature film to come from Jordan in decades, and it reflects a slow but distinct movement into movie production in some of the Middle-Eastern countries where conservative religious views have long suppressed it. Captain Abu Raed is technically polished and makes considerable use of Amman cityscapes and ancient ruins as backdrops for the action. It’s also definitely a crowd-pleaser, judging by the sold-out audience I saw it with.

Another rarity is Australian director Benjamin Gilmore’s first fiction feature, Son of a Lion (2007), which he filmed entirely in the Peshawar region of Pakistan. That’s an area adjacent to the northwest border of the country with Afghanistan, notorious as a refuge for Taliban fighters and probably Osama bin Laden. The program lists Son of a Lion as an Australian/Pakistan production. I doubt any Pakistani funding went into it, but Gilmour wrote the script with the advice of the local people, and non-professionals play all the characters. The credits also contain quite a few Pakistanis performing tasks behind the camera.

The story seems inspired in part by the “child’s quest” narratives of the Iranian classics of Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

and Mohsen Makhmalbaf. A strict, traditionalist widower who makes guns wants his 11-year-old son to follow in the family business, while the boy longs to attend school. Apart from his father’s determined opposition, Niaz’s desires fly in the face of the local culture. Gun shops are everywhere, and every male adult seems to be armed. Shopkeeper casually step into the street to fire off weapons to test or demonstrate them. At one point the falling bullet from such random shooting kills a bystander. Between the personal scenes Gilmour intersperses occasional scenes of men sitting around and discussing the situation, debating whether they would shelter Bin-Laden if asked to or turn him in for the reward; they also speculate on America’s image of their part of the world.

Son of a Lion was shot under difficult and dangerous circumstances on digital video (with post-production handled, amazingly enough, by Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post facility in New Zealand). The shots of the beautiful desert landscapes are not up to those we are used to from Iranian films, but they manage to suggest the grandeur of the area and to give a fascinating and humanizing insight into a region which the American government and media portray as merely a hotbed of terrorism.

Moroccan films are not quite as rare as these, but they’re certainly not common. As Burned Hearts (Morocco/France, 2007) was being introduced, I realized that the only other Moroccan film I had previously seen was by the same director, Ahmed El Maanouni. That had been Trances, a semi-documentary1982 film about a touring pop-music group. It was shown last year at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, having been the first film restored by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Founda tion.

Burned Hearts was another film that seemed to transport me back to the 1970s art cinema. A young man returns to his childhood home after being educated as an architect in Paris. His tyrannical uncle is dying, and flashbacks present the painful memories evoked by the familiar sights and sounds of the city, this exploration of the character’s mental paralysis, along with the black-and-white cinematography of the locations, evokes both Duras and Antonioni. But El Maanouni refuses to concentrate solely on the hero’s concerns, bringing in several intriguing characters from the neighborhood and having groups spontaneously break into song and dance in the streets and shops.

Melodramas from Mexico

These films all come from regions seldom represented in international film festivals, but Mexican cinema  has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

has had a growing presence in such venues in recent years. Two I’ve seen so far are very different from each other. The Desert Within (Desierto adentro, 2008), Rodrigo Plá’s second feature, already has a reputation after winning a cluster of prizes at the Guadalajara Film Festival. A period piece beginning in the late period of the Mexican revolution and extending into the 1930s, it tells the story of a peasant who inadvertently brings destruction on his village and decides that the only way to expiate his guilt is to drag his family far into the desert to build a church. The film takes a bitter view of Catholic guilt, with the protagonist forcing suffering, sexual frustration and death upon his children as his obsession grows.

The other Mexican film, All Inclusive (2008), deals with another family crisis, but one which takes place over a few days in a luxurious resort on the “Mayan Riviera.” The story is slickly told by director Rodrigo Ortúzar Lynch and beautifully shot by Juan Carlos Bustamante, but I found the story forumulaic. A man who has just been told that he has only a short time to live, goes on vacation with his family, whom he has not informed of his condition. As he struggles with his secret, his wife and three children undergo their own crises. One daughter faces up to the fact that she is a lesbian, the son becomes entangled in an online “affair” with another man’s girlfriend, and the wife, assuming that her husband is being unfaithful, allows a young scuba instructor to seduce her—all this observed by the sardonic goth daughter.

As the tensions grow, a hurricane approaches, and the climactic set of revelations and reconciliations come just as it hits. During the narrative, each of the troubled family members manages to find someone gorgeous willing to bed them and/or hear their tales of woe. The idea that the bearish husband, seeking escape in a local bar, would run across a stunning 23-year-old Cuban woman who would take him into her home, listen at length to him, and finally, of course, teaching him to enjoy life. This gives him the courage to return to his family and tell them the truth. Once the family members have bared their soles, they become a jolly, well-adjusted bunch. It’s an entertaining story with likeable characters and touches of humor—but it’s a bit too much to believe.

Americans in Canada

Apart from Craig Baldwin’s Mock Up on Mu, which David will cover, I’ve seen two American indies so far. Momma’s Man (2008) is directed by Azazel Jacobs. It deals with Mikey, a man traveling on business who has problems with his flights and ends up staying with his parents in their New York loft. Finding excuses not to return to his wife and baby in California, he fritters away his time by reverting to his childhood pursuits. The film takes the daring step of being centered on an unsympathetic character who is the point-of-view figure for all but a few scenes. It manages to convey his gradual move from indecision to obsession and eventually a full-blown breakdown in a believable fashion.

Part of the appeal of Momma’s Man comes from the fact that Mikey’s parents are played by Ken Jacobs, the great experimental filmmaker, and his artist wife Flo Jacobs. It is set in their actual New York loft, a maze of odd filmmaking devices, accumulated pop-culture artifacts, and artworks. The two give extraordinary performances, managing to seem wise and caring and at the same time obsessive and eccentric to a degree that might have contributed to Mikey’s breakdown. Although Jacobs cast an actor as Mikey, one has to suspect that the film is at least somewhat autobiographical, and the casting of his parents has created a uniquely convincing portrait of a family.

David and I were delighted to see RR (2007) on the program. It’s the latest feature by American avant-gardist James Benning. Jim is an old friend, having been a graduate student in our department at the University of Wisconsin-Madison during our early years there. He has concentrated largely on landscape films, usually consisting of lengthy, static shots. This one consists wholly of distant views of trains in what appear mostly to be western and Midwestern locations. In virtually every case the shot holds until the entire train has moved through the shot or out of sight—or stopped, in a few cases.

As so often happens with structural films, small variations become evident to the alert viewer. A shot of a  car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

car stopped for a train passing through a small town contains tiny reflections in the windows of a nearby house that may draw the eye. Some trains are covered with spray-painted graffiti, while others are pristine. One is led to speculate about what the cars may be carrying, and there is a hint of social comment in that activity. A considerable portion of most of the trains consists of tankers, presumably carrying the gasoline or other petroleum products that are currently causing so much trouble in our economy. Others contain numerous livestock cars, and one lengthy train contains nothing else. Among the views of many freight trains, we are treated to a glimpse of a single very short passenger train zipping through the briefest shot in the film.

RR draws us to enter into perceptual play, often with a distinct touch of humor. Few of Jim’s films have contained the measure of their shot length in their mise-en-scene so decisively. The length and speeds of the trains determine the duration of the shots, and one learns to watch for the number of engines pulling or pushing a train as an indicator of how long the train is likely to be. A few shots show trains moving slowly and decelerating at an almost imperceptible rate, teasing us as to whether they will stop altogether and whether the shot will end if they do. At times a train may move through the shot, only to reveal another on a parallel track. One shot plays a very clever game with us. I won’t reveal what it is, but the shot comes perhaps a third of the way through: an oblique view along a track with bushes prominently in the foreground and a short, arched underpass in the middle distance.

Jim has continued to shoot in 16mm in an increasingly digital age, and he consistently manages to make gorgeous images that look more like 35mm. The last one of RR, involving a vast wind farm, is a stunner.

Captain Abu Raed.

David here:

An unusually good VIFF, with many films to get your eyes open.

Enter the Dragons, with Tigers

As usual, the venerable Dragons and Tigers thread is offering some remarkable new films from Asia. The Good the Bad the Weird lived up to its reputation, not to mention its title, offering frenetic action and comic-book (in the good sense) bravura. Sell Out!, a Malaysian satire of corporate maneuvering and media brainwashing, doesn’t get points for subtlety—the goliath is called the FONY corporation—and sometimes it tries too hard. Still, it’s likeable enough, and the fact that it’s a musical adds a welcome bit of froth. The funniest bit, for me, was the opening parody of an art movie, which does actually get integrated into the main action.

Two late works by long-time Japanese directors offered a study in contrast. Kitano Takeshi’s Achilles and the Tortoise starts out sweet and ends very sour, not to say bitter. In telling the story of a boy whose spontaneous love of drawing is forced into narrow commercial channels, Kitano suggests that art is a racket. Across the decades, schools and galleries push the pliant, nearly comatose young artist to create a signature style. He is told to be original, but also he must harmonize with fashion and tradition. With a grim obstinacy he tries to fulfill what the business demands, and to the end he is still trying.

Achilles is less willful than Takeshis’ and Glory to the Filmmaker!, and it tells a more coherent tale, but their glum narcissism is still in evidence. The film cries out for an autobiographical interpretation: is the naïve filmmaker corrupted by exposure to international art cinema? Pictorially, there’s some confirmation of this: Kitano seems to have abandoned his early films’ ingenious use offscreen spaces and planimetric compositions. Like his hero, who can’t achieve artistic singularity, Kitano has become a surprisingly academic and anonymous stylist.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

One can’t claim high originality for the style of Wakamatsu Koji either, but at least United Red Army has a gripping premise. The 1960s student movement was driven by opposition to the war in Vietnam and Japan’s cooperation with US policy, but in the following decade some factions emerged that were committed to violent revolution. Small cadres sequestered themselves in mountain cabins. Their exercises in “criticism and self-criticism” devolved into games of increasingly murderous aggression.

Wakamatsu’s technique is unstressed: No fancy angles, neverending tracking shots, or virtuoso compositions, just a businesslike application of today’s wobbly handheld look. The cunning lies in the film’s structure. After a half-hour montage summarizing the formation of the group, we are carried into the hideouts and watch the punishment grow more feverish and self-destructive under the domination of two leaders who seem parallel to Mao and Madam Mao.

By the end of the second hour, the remains of the army are on the run, struggling through vast snowy landscapes. Soon four survivors straggle into a ski lodge, hold the owner’s wife hostage, and face their final challenge: wave after wave of police assaults. Waiting for the inevitable outcome, the survivors spare time for grim humor: On 28 February one remarks, “I’m glad the all-out war won’t be tomorrow. Then my death anniversary could come only every four years.” And they can pause for an exercise in political discipline. After a lad takes an extra cookie, he criticizes himself. Stern reprimand follows: “That very cookie you ate is an anti-revolutionary symbol.” Unsentimental and unsparing, United Red Army is over three hours long, with not a longueur in sight.

A man parks his car to pick up some cake at a bakery. He has been away from home all night; now he’s rude to the lady behind the counter. Having bought a couple of cakes, he finds that a sinister black car has double-parked and hemmed him in. His efforts to find the owner lead to a spiral of comic and pathetic confrontations with an orphan child, burly Triads armed with whitewash, and a pimp with a distinctly bad haircut.

Creating something of a network narrative, Chung Mong-hong’s Parking in its modest way offers a cross-section of Taiwanese society, from the prostitute brought over from China to a jaunty barber who more or less controls the switch-points of the story. The ending will strike some as dovetailing all the cards a little too smoothly, but I found it satisfying, if only because it lets our haughty hero show unexpected resilience and compassion. This is only Chung’s second feature, but his work bears watching.

For once, it really is rocket science.

If you’ve already figured out the deep connections among Scientology, the aerospace industry, ritual sex magic, New Age spirituality, and the migration of Los Angeles hipsters to San Francisco in the 1950s, Mock Up on Mu won’t come as news. If, like me, you haven’t the faintest idea about the cat’s-cradle ties among these cultural phenomena, Craig Baldwin’s latest collage-essay-epic-lyric-narrative (all terms he applies to it) is the very thing you need. It’s as exuberantly peculiar as his earlier work like Tribulation 99 and Spectres of the Spectrum, flooding us with a relentless voice-over that splits off from and reconnects with the torrent of images grabbed from all manner of movies.

These earlier films had stories of a sort, swollen conspiracies and ominous coincidences that make Baldwin the eccentric cousin to Fritz Lang. But Baldwin says that these stories couldn’t really engage people, couldn’t get them to identify. Mu tells a more personalized tale. L. Ron Hubbard, founder of Scientology, has colonized the moon and sends Agent C to earth to arrange for people to be shipped up. Agent C runs afoul of Lockheed Martin, corrupt aerospace executive, and becomes attached to Jack Parsons, an early rocketeer who in the 1950s assumed the secret identity of Richard Carlson, so-so Hollywood actor. Meanwhile, Aleister Crowley rules a secret society at the center of the earth….

Or maybe not.

Actually, I won’t swear to much of what I just said. Baldwin’s phantasmagoria tests my memory, as well as plausibility. The story line is swallowed up by what he calls footnotes—swarming digressions, tangents, and flashbacks which are conjured up in imagery that shoots off in a dozen different directions. A few frames from a kiddie science movie or a grade-Z space opera, juxtaposed to Parsons’ rapid-fire account of the history of rocket testing, whiz by almost subliminally.

In any case, there are characters and a more or less linear story. But Baldwin is Baldwin, so things can’t be so simple. He has for the first time staged and shot footage of actors, and their scenes form a sort of string that you can follow. But just as crystals grow in fantastic array along a string, alien footage exfoliates out from the staged scenes. Baldwin aims, he says, at “a dialectical density.”

The result is a narrative experiment I’ve never seen before. With a simple cut, our characters are replaced by figures from other films, who become, in some spectral fashion, both alien inserts and our characters.

Confused? Here’s an example. Agent C (who will turn out to be Marjorie Cameron, muse of many West Coast artists) is riding with rocket scientist Jack Parsons. A series of shots shows them in the car’s front seat.

As the scene goes on, one character gets replaced by another.

Eventually both of our originals have been replaced.

The stand-ins can even change position as the dialogue continues uninterrupted (but always mis-synchronized).

The cuts make the inserted characters surrogates or avatars for our people, but they retain wisps of their original, enigmatic existence. They also remind us that situations like driving in a car are genre stereotypes, schemas so common that individual instances can serve as place-holders for one another. Yet the shots always return to the original actors, anchoring the associations and keeping at least one plane of the narrative moving forward.

These phantasmagoric shifts make the identity transformations in I’m Not There look labored. In Mock Up on Mu Baldwin may have found a new method of cinematic storytelling. Don’t expect Hollywood to pick it up soon.

Pulling half away

How do you tell your audience what it needs to know to understand what it’s seeing, and what it will see? A film can handle exposition (aka backstory) in several ways. Most films favor concentrated and preliminary exposition: Most information is given in one spot and quite early on. This is when you get the opening dialogue when characters say to one another: “Look, you’re my sister. You can tell me.” (Ohh…They’re sisters.) Concentrated, preliminary exposition is usually clunky, but it can be done with finesse, as in the opening soliloquy of Jerry Maguire.

The major alternative is distributed exposition, where information about the backstory is spread out, evenly or unevenly, across the film. This is common in mystery films (as when, under pressure, characters start to confess their relation to the murder victim) and in “puzzle films” like Memento, where we only gradually understand the relations among the characters. Delayed and distributed exposition in straight dramas is common in European art cinema, but it’s rare in the US, although independent films like Claire Dolan and Man Push Cart have made good use of the technique. Kristin already mentioned a similar strategy at work in Eat, for This Is My Body.

Lance Hammer’s Ballast comes garlanded with praise from festivals and major news outlets like the New York Times. For once the advance word is justified. I thought that Ballast was an exceptional intimate drama, focused almost entirely on three people and their layered relationships in a country town in the Mississippi Delta.

At this point I should mention how the three principals are connected, but part of the daring of Hammer’s film is to postpone, for almost an hour, telling you such things. He says he wanted a film that is, like the Delta, “spacious and quiet and slow.” Here the very issue of what we need to know is put into question. By blocking our knowledge of characters’ relationships, Hammer forces us to confront moments of action in a pure state. Each instant, each shot even, gains an integrity and gravity it wouldn’t have if we knew the full dramatic context.

Take the opening. After a brief, wordless prologue showing a boy in a field of crows, we’re in a vehicle pulling up at a bungalow.

The indistinct figure of a man goes to the door. Inside, a brief shot shows a black man’s face in silhouette.

Soon, the first man, who is white and weatherbeaten, is seen at the door, expressing concern for the man inside.

The white man enters, wrinkles his nose at a smell, and proceeds to another room, where a figure, turned from us, lies on a bed.

The black man continues to sit impassively before his TV, though now we can see his face more clearly.

Who are these men? What connects them? Who has died? An ordinary film would tease us with these questions but answer them fairly soon (say, in the next three or four scenes). Here, we will have to wait a considerable time to find out the answers. In the meantime, what we have registered in place of an action arc is the atmosphere of shock, sorrow, grieving, and lowering skies. And almost immediately a rather dramatic event will occur, nearly offscreen, and its causes will remain equally opaque for quite some time.

Ballast’s delay in spelling out its story premises is sustained by two unusually quiet main characters. Lawrence, the man sitting in the darkness, leads a solitary life and speaks reluctantly and briefly. Likewise, the boy James is often silent or alone. These two don’t soliloquize, and they live one day at a time. We must simply observe their behavior, try reading their minds, and more generally absorb the emotional tenor of their lives.

The sparseness of the exposition also puts us on the alert for any scrap of information that will fill in the blanks. For instance, references to “the store” flash out as clues to possible connections among the characters. Hammer’s strategy demands that the audience exercise a degree of patient concentration that most films never ask for.

For roughly the first half of the film, then, Hammer’s narrational technique creatively impedes our full understanding of the basic givens of the story. Once the relationships have coalesced (though there are still some revelations to come), the dialogue becomes more explicit and, some would say, the drama more traditional. But the visual narration continues to mute and elide dramatic moments. At some points pieces of action are rendered opaque by the bobbing, jump-cut camerawork. Most memorably, a clumsy embrace is hidden by a “wrong” camera setup, all the better to make us wonder about the impulses behind the gesture. Hammer matches his oblique plotting with an oblique visual style.

Hammer has cited Bresson as an inspiration, and in conversation he also mentioned late Godard, who has become willing to avoid exposition for nearly an entire film. Unlike Godard, who seems to revel in the pure artifice of withholding information, Hammer appeals to realism: The gradual piecing together of the narrative, he remarked to me, is like our coming to know people in life, bit by bit.

Correspondingly, by the end of Ballast we come to feel more empathy for Hammer’s characters than for Godard’s, and possibly even for most of Bresson’s enigmatic souls. But the empathy doesn’t come cheap, and it isn’t wallowed in. The climax is brushed past in one sideswiping shot; blink and you’ll miss it. In another interview, Hammer speaks of “putting something out and pulling half away.” By leaving us to fill in that half, Hammer exhibits his respect for his characters, and for his audience.

Mock Up on Mu

P. S. For dispatches from 2006 and 2007 editions of the VIFF, type Vancouver into our search box.