Archive for the 'National cinemas: Taiwan' Category

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Two Chinese men of the cinema

A Brighter Summer Day.

DB here:

This summer two major figures in Chinese filmmaking died. One was Edward Yang (Yang Dechang), one of Taiwan’s finest directors, who died on 29 June. But before I pay tribute to him, I want to acknowledge another figure who had a great impact on Asian cinema.

Charles Wang died on 6 July. Along with his brother Fred, Dr. Wang ran Salon Films, the major supplier of film equipment for Hong Kong and a principal one for East Asia and the Pacific Rim. Charles graduated with a degree in chemistry before inheriting the business from his father. As Hong Kong filmmaking grew in sophistication, Salon grew along with it. Most Hong Kong films bear the firm’s brand in their end credits.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

Since 1969 Salon has provided top-flight cameras, lenses, lighting gear and other technical support for both local and visiting productions, such as Mission: Impossible III‘s Shanghai shoot. An early triumph was winning the Panavision franchise for the region. The company even supplies trampolines and landing cushions for martial acrobatics, as this glimpse inside a Salon van shows.

When I interviewed Dr. Wang in 2003 he kindly gave me information about the company and the development of film technology in Hong Kong. He showed me his many awards and talked enthusiastically about Salon’s new efforts to assist mainland moviemaking. In recent years, Salon was investing in films such as Zhang Yimou’s Hero. Like most Hong Kong film people, he was very accessible and generous; he even gave me a lift back to my hotel. Charles Wang was a major force in the Hong Kong industry and will certainly be missed.

Laconic cuts and long takes

I met Edward Yang twice. First, at a Hong Kong Film Festival reception, we chatted about his film Mahjong (1996), which had screened. I got to know him a little better in fall of 1997, when we were both invited to the Kyoto Film Festival. We ate and watched films together, and we shared baby-boomer nostalgia; it turns out that he and I (and Hou Hsiao-hsien) were all born in the same year.

I found him friendly, thoughtful, and open to appreciating all film traditions. He spoke of enjoying Japanese swordplay movies in his youth, and he admired American films for their gripping stories. Still, his preference for ellipsis and understatement came through. When we met Kitano Takeshi for dinner, Edward praised a crisp transition in Sonatine: to show the gang going from Tokyo to Okinawa, Kitano simply gives us a quick pan of the sky accompanied by the sound of a jet plane.

Yang was an accomplished cartoonist, and I thought that this background partly explained his early style, on display in the short film Desires (1982) and in the features That Day, on the Beach (1983), Taipei Story (1985), and The Terrorizers (1986). In these films Yang often breaks his scenes into simple but striking fragments. After the police shootout in The Terrorizers—one of the most enigmatic and elliptical opening sequences in modern cinema—the Eurasian girl staggers out to the street. Yang gives us her collapse in quite abstract, percussive images. Her foot hits the pavement. Cut. She takes a step and falls out of frame; the camera holds on the empty frame. Cut. She’s lying on the crosswalk. I imagine these as forceful, laconic comic-book panels.

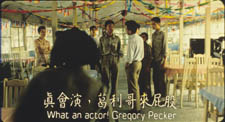

With A Brighter Summer Day (1991), my favorite of his works, Yang tells another gap-filled story but treats the scenes in long, distant, often decentered takes reminiscent of Hou. Now his frames are more dense with figures and furniture, and layers of action extend quite far back. In Figures Traced in Light, I devote a little—too little—analysis to one admirably staged passage. Another of my favorite scenes in A Brighter Summer Day shows the hero Xiao S’ir developing a romantic attachment to Ming, the girlfriend of the absent gang leader Honey. They sit in a brightly decorated café.

Suddenly Ming darts out of the shot, leaving Xiao S’ir and the other boys staring. From their point of view we see that Honey, dressed in a sailor suit, has returned and Ming has gone to meet him.

Yang cuts back to the boys as Honey’s gang starts to threaten Xiao S’ir. Abruptly, Ming runs into the shot, past the boys, down the long central aisle, and out of the café. (In a 35mm print you can see her pausing and lingering outdoors.)

The group closes around Xiao S’ir; only Honey’s entry breaks the tension. He leads the boy into the depth of the shot, the camera following them.

Honey warns Xiao S’ir off, and our hero goes outside, mimicking the path Ming had followed.

As Honey turns his attention to his gang and an upcoming skirmish with their rivals, he moves back down the aisle, the camera backing up. Once his business is done, Honey drifts back to the rear door.

Honey pauses far from us, at the window. Yang cuts to show what he sees: Xiao S’ir, in flagrant violation of the warning, talking to Ming outside.

First we got Xiao S’ir’s point of view on Honey and Ming; now, in a reversal, we get Honey’s point of view on Ming and Xiao S’ir. In scenes like this, Yang merges his developing skills in long-take staging with cuts that develop not only the action but story parallels. Very distant framings, characters moving to the rear of the shot and turning their backs: Yang “dedramatizes” the scene. Further, by shifting point of view, he leaves us guessing about story information: What led to Ming’s running away from Honey? What are Xiao S’ir and Ming talking about now? Yang created a laconic visual approach that, I’d argue, invests fairly standard dramatic situations with a tantalizing uncertainty.

Yang’s best-known film is, of course, Yi Yi (2000), and it won him the wide appreciation that he had long deserved. It’s a warm and gentle work, less innovative than his earlier efforts but utterly typical of his vision of lives pervaded by melancholy routine and abrupt disappointment. People often remarked that the adolescent hero of A Brighter Summer Day resembled Edward himself. Perhaps too in Yi Yi Yang’s enigmatic pictorialism is echoed in the idea of a little boy who makes photographs of people’s heads seen from the rear. Like the director, the boy (named Yang-yang) displays a reticence that respects the mysteries of people’s private lives.

We already have a very useful guide to Yang’s work in one chapter of Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh and Darrell William Davis’ book, Taiwan Film Directors. And Criterion’s Curtis Tsui has done a wonderful edition of Yi Yi, as Brian Hu shows here. We must hope that Criterion, Eureka, or another gilt-edged DVD publisher will soon bring us Yang’s other works in the pristine editions they deserve.

A Brighter Summer Day (1991)

In 1998, when we screened A Brighter Summer Day at our Cinémathèque, I wrote a program note. I reproduce it, lightly revised, as a quick pointer to one of the great films of the 1990s.

With Taipei Story (1985) and The Terrorizers (1986) Edward Yang established himself as one of the two leaders of the Taiwanese New Wave generation. At first it seemed that he and Hou Hsiao-hsien had agreed to a division of labor in their subjects and styles. Hou tended to concentrate on life in the countryside, or on rural characters transplanted, bewilderingly, to the modern city. Hou was also deeply interested in the history of Taiwan; his most acclaimed film, City of Sadness (1989), is a panoramic survey of Taiwanese society immediately after World War II. Hou’s tranquil style favored a contemplative mood and muted emotion.

Yang, by contrast, tended to focus on the lives of well-to-do urbanites in a contemporary setting, Taiwanese yuppies plagued by anomie and the desperation of love and work. His elliptical editing technique, reminiscent of Resnais, fractured time and space, while his compositions had a painterly starkness. The Terrorizers shuttles kaleidoscopically among characters at its beginning; their relations only gradually settle into intelligible patterns. Whereas Hou tended toward nuance and quiet drama, Yang was unafraid of shocking, inexplicable bursts of bloodshed.

Now it seems evident that this impression of a division of labor was somewhat schematic. Hou’s range of interests has widened, with new emphasis on the violent world of urban crime (Goodbye South Goodbye, 1996), and he has come to rely on quite disorienting transitions between past and present (Good Men, Good Women, 1995). Likewise, with A Brighter Summer Day Yang turned to history and cultivated a more sober style of filming, with lengthier shots and a fixed or barely moving camera. This approach throws down a challenge to the razzle-dazzle of contemporary popular cinema—from Hollywood, Hong Kong, and even the American “independents”—and invites us to scrutinize, moment by moment, the details of action unfolding on the screen.

Three years in the making, A Brighter Summer Day was a triumph of independent production. At a period when the Taiwanese film industry was virtually dead, Yang found money (mostly Japanese) to mount a project of remarkable ambition. Over half the cast and crew had never worked on a film before. At first released in a three-hour version, the film was re-released in a four-hour director’s cut, and this has become the standard version.

The historical event examined in A Brighter Summer Day took place in Taipei in the 1960s, when an adolescent boy about Yang’s age stabbed a young woman. At epic length Yang creates a web of circumstances around the event. He shows the interplay of traditional culture—filial duty, education as an ideal of social advancement—with popular culture, especially the rock n’ roll songs that recur throughout. Yang has said that Americans might not realize the shattering force of rock in other cultures: “These songs made us think of freedom.”

The film has over eighty speaking parts, most filled by nonactors, and it intertwines several characters’ destinies. On first viewing, the film can be somewhat bewildering to a non-Taiwanese audience, so a plot sketch may help. (Skip to the next paragraph if you don’t want to know the action in advance.) At the center is fourteen-year-old Xiao Si’r. He tries to be a dutiful student, but with his friends Cat and Airplane, he lives on the fringes of the Little Park gang of teenage thugs. When Xiao Si’r reports seeing a gang member with another boy’s girlfriend, he triggers a power struggle in the gang. As his friends fall by the wayside and rival gangs fight for control of local turf, Xiao S’ir becomes involved with Ming, a girl who’s attached to Honey, exiled leader of the Little Park gang. A major climax occurs during a gang rumble at a rock n’ roll concert. Interwoven with the juvenile intrigues are political matters; the police pursue and question Xiao S’ir’s father about his Communist friends. Xiao S’ir becomes friendly with Ma, a general’s son, before they start to compete for Ming’s favor. The rivalries build to a tense schoolroom confrontation and a tragic finale in the park. In the final scene and over the credits, a radio transmission broadcasts the names of the students who have passed their school entrance exams.

The plot is even more intricate than my bare-bones summary can indicate; I haven’t discussed the boys’ adventures in a film studio or Cat’s singing career or the slender line of action involving Xiao S’ir’s sister. The breadth of action is extraordinary, and a sense of the contradictory pulls of daily life emerges steadily. No less demanding is Yang’s style—scenes played in darkness, few close-ups, with medium-shots and long-shots keeping us at a distance from the characters. But the result is a dispassionate look at teenaged passions, a deromanticized treatment of young people growing up in a repressive milieu. A Brighter Summer Day (the English title comes from Elvis Presley’s “Are You Lonesome Tonight?”) is an elegy to the ideals and mistakes of youth, an analysis of the vanities of the male ego, and a view of a generation painfully facing the limitations of tradition, the constraints of political oppression, and the demands of the modern world.

Yi Yi.

Vancouver envoi

A late night Thursday, and a snoozy day of traveling on Friday, kept me from posting ASAP. And now on Saturday morning—I can’t get on to my own blogsite! Apparently others can. So while our web czarina Meg fixes things, I try to wrap things up on my visit to the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Le Petit Lieutenant: A policeman’s lot is never a happy one. From Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct to Ian Rankin’s Rebus series, modern crime novels give an emotional resonance to police procedure by showing the psychological costs of being exposed to cruelty, chicanery, and death. American cop movies have gradually let more of this quality come through (Prince of the City, Heat, Dark Blue), and of course TV, from Hill Street Blues to The Wire, has turned the police procedural into urban melodrama. But the French got here first. For decades, their cop movies have been world-weary psychological dramas shot through with bitter realism. Think of Corneau’s Police Python 357, Pialat’s Police, Tavernier’s L.627, or any of Melville’s policiers.

Le Petit Lieutenant, which I saw on my last day, falls into that sturdy tradition. The premise—a string of attempted murders of bums and passersby—is played out with the usual clue-by-clue plotting, but we also witness the strained lives cops lead. Our two protagonists are the overeager recruit Antoine (Jalil Lespert) and his recovering alcoholic supervisor Carolina (Nathalie Baye in an utterly deglamorized performance). Xavier Beauvoi’s narration shuttles skillfully between their points of view, leading to a good deal of sympathy and suspense and a grim but plausible climax. One of several nice touches: the cops keep movie posters over their desks, and if I’m not mistaken, in some cases the posters serve as hints to the cops’ personalities. The ending leaves you as bereft of certainty as the protagonist.

Do Over (Taiwan): For a finale, I caught this extraordinarily ambitious movie by the twenty-eight-year-old Cheng Yu-chieh. Shot in anamorphic widescreen (very rare in Taiwan over the last twenty years), it belongs to the trend I’ve called “network narratives.” Across New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day, the lives of several people converge and diverge in the fashion of Short Cuts and Magnolia. Each character’s strand evokes a different genre: gangster movie, romantic drama, twentysomething “relationship” comedy, and the movie about moviemaking. Each strand is also set off by a distinctive photographic style, from misty blue to grainy, blown-out noir.

A network plot often exhibits an interesting mix of realism (in life, strangers’ lives do become tangled) and artifice (chaptering, repeated scenes, and other overt narrational devices). The artifice becomes flagrant at the film’s end, when Do Over‘s title gets literalized and the plot lines are revised to yield alternative endings. The cleverness doesn’t get the upper hand, however, and this remarkable debut leaves you both satisfied and looking forward to Cheng’s next film.

After two trips to Vancouver’s festival, I have yet to go to any tourist destination. I’ve lived within a few square blocks, dashing among hotel, DVD stores, and the Granville Multiplex, with forays to the Pacific Cinematheque and the Vancity Theatre and sushi restaurants and crepe cafes. I’ve lived a film-wonk holiday across eight days and dozens of movies. Thanks to Alan Franey, the Festival Director, for inviting me and extending me so much courtesy. I’m grateful to all the help of his colleagues PoChu Au-yeung, Mark Peranson, Eunhee Cha, Steve Martindale, and Jack Vermee. I wish we’d had more time to talk! Over the last two visits, I’ve made new friends from all over the world, and I’ve enjoyed just sitting among exuberant audiences.

Tony Rayns has been programming Asian films at Vancouver since 1988, and I have to note the melancholy news that he’s stepping down as coordinator of the Dragons and Tigers competition. I’m unhappy as well that I can’t be at Vancouver tonight (Saturday) to see the results of the competition and participate in what will surely be a string of tributes to Tony. So here’s a weak substitute—my own appreciation online.

Tony Rayns at VIFF, 2006

In Tony Rayns deep expertise is joined to an unmatched passion and curiosity. His Vancouver programming was crucial in introducing directors like Kitano and Hou to West. He has also made films happen: Without the acclaim of Vancouver audiences and the prestige of the Dragons and Tigers prize, how many distributors would have backed later work by young directors over the last twenty years?Most critics prefer to stroll into screenings to watch films that miraculously appear, thanks to the work of dozens laboring behind the scenes. From the start Tony got his hands dirty. Apart from writing discerning and literate film criticism, he worked for film festivals, wrote presskits and program notes, translated subtitles, and pushed for offbeat films to be available on video and cable. Above all, he programmed films, backing his tastes with an expanding network of allies in the film industry. He helped create a climate of opinion that welcomed the burst of creative accomplishment that Asian film has offered over the last three decades.

Tony’s been a friend since the mid-1970s, and his influence on my tastes and thinking has been immense. I wouldn’t know a lot of what I know without his tireless proselytizing for once-obscure films and filmmakers. He’s sensitive to all a film’s dimensions—its social and artistic implications, its relation to the director’s personality and life experience. A late-night conversation with him, preferably over Asian food, is like being in the liveliest seminar you ever took.

Many of Tony’s contemporaries—I know plenty—have given up on contemporary cinema. Who can blame them, after a trip to a multiplex? Too often, cinema seems over. But this has only made Tony dig deeper, watch more widely, and remind us that this art form is still frisky, unpredictable, and occasionally rapturous. The French have a word for it: animateur, the person who sends a jolt of energy into a culture. Like André Bazin and Henri Langlois, Tony is one of the animateurs of world cinema, and everyone who loves film is in his debt.

Mostly Asian, and why not?

David here:

A correspondent asks: Why am I spending so much time at the Vancouver Film Festival watching Asian movies?

Well, I have dabbled in other regions. Most recently, I enjoyed Eugène Greene’s short Signs, a metronome-and-protractor movie that nonetheless harbors a sharp sting of emotion. More straightforwardly entertaining was Aki Kaurismaki’s Lights in the Dusk. You’ve seen the story’s premise before, both in film noir (femme fatale dooms hero) and in other Kaurismaki films (loser comes stubbornly back for more trouble, and gets it). But it’s as usual filmed in a laconic, Bressonian way, and we get another Kaurismaki protagonist who is blank-faced, obstinate, more than a bit thick, and, despite everything, quixotic.

Still, Asian films have come first for me, as for many others here. Why? The evidence is clear: Since the 1980s, movies from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Mainland China, South Korea, and more recently Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines have offered an almost unrivaled range of accomplishment. (Want names? Tsui Hark, John Woo, Wong Kar-wai, Kitano Takeshi, Kore-eda Hirokazu, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, Jia Zhang-ke, and on and on.) The energy hasn’t flagged, and Vancouver has been in the forefront of supporting this tidal wave of talent. Tony Rayns’ brilliant programming has set an international standard, and the festival’s Dragons and Tigers competition for first features have brought many young filmmakers to world attention.

So herewith some more outstanding Asian revelations from my final Vancouver days:

Hana: Kore-eda keeps surprising us; each film is quite different from the one before. In a downtrodden neighborhood of Edo (the old name for Tokyo), people live in mud and dung, struggling to get by. Some of the loyal 47 ronin wait impatiently to avenge their executed lord, while a young man hangs around trying to find his father’s killer. But the fact that the youth is a fairly inept warrior tips you off to the essentially comic vision underlying this warm movie. Add in a bully who isn’t actually a bad guy and a gallery of low-life neighborhood types, who pass the time rehearsing a play that unwittingly satirizes the samurai ethos. The result is a film that probes the righteousness of vengeance with tact and vulgar humor. Everybody I know wanted to see this again, right away.

My Scary Girl (Korea): The Trouble with Harry meets The Forty-Year-Old Virgin. Dae-Woo has never had a date, but he decides to start with his cute neighbor. He doesn’t know that she’s a Woman with a Past, not to mention a fairly worrisome Present and an ominous Future. Romantic comedy shifts to black comedy, and bowling pins mix with lopped-off fingers. It’s a crowd-pleaser, and Hollywood will probably rush to remake it. But will an American director have the guts to keep the very logical but not wholly happy ending?

I Don’t Want to Sleep Alone: Taiwanese director Tsai Ming-liang has provocative ideas and burnished imagery, but sometimes I’ve thought he’s too clever by half. This movie, his first in his native Malaysia, won me over because it seems to play to all his strengths. Four people intersect around, under, and on a mattress, with an extra character as a kind of comatose sentinel. Tsai’s gorgeous imagery isn’t just pretty for its own sake. Like Tati, he can design compositions which are actually funny, and his long takes give us time to probe the textures and crannies of staircases, a building site, and ordinary streets. The film’s last shot is alone worth the price of admission.

No Mercy for the Rude (Korea): This time the hitman is a mute (or is he?) vowing to kill only the really bad people, and hoping to accumulate enough pay to afford an operation on his “short tongue.” He falls in with a street kid and a hooker, and as the seriocimic plot unfolds we get the very Asian insistence that childhood innocence can be recovered even in the midst of carnage. The film indulges in some flights of fancy—a hitman’s picnic, a hitman who’s a ballet dancer—before coming to its satisfying end in, of all places, a bullring.

Faceless Things: Warnings about gay sadomasochism to the contrary, this doesn’t offer much you can’t see in Warhol or Waters. What it does provide is three shots. The first, nearly 45 minutes long, provides virtually a one-act play about a motel tryst between a businessman and his teenage lover. The second shot shifts us to an anonymous sexual encounter that is admittedly fairly off-putting, but handled with the mix of casual framing and off-kilter suspense we find in, again, Warhol. The very last shot is very brief and puts the other two into a new context. Director Kim Kyong-Mook is only in his early twenties, but his ambition and daring make him a filmmaker to watch.

My last night has come all too soon. So just to make sure that the Europeans are still at work, I’ll check on the French cop movie Le Petit Lieutenant. I’ll end with another Dragons and Tigers entry, the Taiwanese movie Do Over.

Maybe a Chinese dinner afterward. Film isn’t the only thing that Asians do well.