Archive for the 'New media: Technology' Category

Rights to revert to author

In the Mood for Love.

DB here:

“They never tell you that.”

My neighbor Jim Cortada is a polymath. He joined IBM in the 1970s, when history Ph.D.s faced bleak prospects for academic jobs. Since then Jim has done everything from selling mainframes to leading seminars on quality management. As a business guru, he writes books on management strategy and tactics. He also writes both popular and academic books on the history of information technology. He finds time as well to write books on his grad-school specialty, Spanish diplomatic history.

Jim’s Amazon listing consists of fifty titles. He has worked with publishers as small as Lulu and as big as Oxford. So when he talks about the nuts and bolts of publishing, I listen. His reaction to what happened to me recently is as succinct as it as accurate: They never tell you that. Put into proper context, it’s good for young academics to keep in the back of their minds.

The Syndics speak, after prodding

14 Amazons.

Early this spring, when my royalty statement from Harvard University Press arrived, I noticed an anomaly. From early 2000 through the end of 2007, Planet Hong Kong had sold about 7000 copies. The average, about 800-900 copies a year, isn’t much for trade books, but fairly solid for an academic title. Perhaps courses on Hong Kong film were using it as a text.

But the newest royalty statement brought me up short. In calendar 2008, the sales dropped off the cliff. Harvard shifted only 85 paperback copies and virtually no hardcovers.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

So about six weeks ago I tried contacting my editor at Harvard. Getting no email replies, I left phone messages. No response.

Mossbacks among you will recognize this as a danger sign. When an editor doesn’t reply, it’s not good news. So a call to Harvard’s editorial offices brought the promise of a prompt response. An email from a good-natured staff member there gave me the lowdown: Planet Hong Kong was being taken out of print. There were too many pictures to make a reprint edition worthwhile, someone had decided. Exactly when was that decision made? That matter was left vague, but I was told that the process of transferring rights to me had already begun.

Actually, I was a little surprised at that. Transferring rights back to the author is an old-media custom, but today, when “multiple platforms” are the new business model, there’s no reason for a book to go out of print. Publishers can keep selling a book through print-on-demand or in digital copies. Why Harvard’s decision-makers chose to revert the rights to me remains a bit of a mystery.

In any event, now the 2008 sales slump made sense. Only 85 copies of PHK were sold that year because in all likelihood Harvard, having decided not to reprint, was simply exhausting its stock of copies. On the basis of past performance, those sad 85 copies probably sold fairly early in the year, so there’s reason to think that the decision not to reprint was taken at some point in 2008, perhaps quite early. Yet I wasn’t informed of the decision until I inquired in 2009.

Nor am I complaining that I wasn’t consulted about the decision. Editors and press directors never tip their hand, for the very good reason that the author has no contractual say in the matter. And telling can only cause trouble, because authors have an annoying desire to keep their books in print.

In particular, academics relish prolonged disputation. If you’re told that your book might be headed for landfill, wouldn’t you launch an ambitious plea for reconsideration, complete with references to all the people you know who love the book and reminders that generations yet unborn will be eager to absorb your ideas? (Quotes from favorable reviews optional.) If tension rises, you can always murmur about feeble marketing efforts and a risibly high cover price. It could all get nasty, and the conclusion is foregone anyhow.

So when the publisher is mulling whether to drop your book, don’t expect to have a vote. But once the press has decided to drop it, why the reluctance to tell you?

I’m the one who’s supposed to kill my darlings

Shanghai Blues.

I’ve now had six books go out of print. Correspondence with regard to two of those, back in the 1970s, is lost in the mists of time. Of the four most recent instances, I was told many months after the decision was made, and by the most impersonal of letters—not from my acquisitions editor but from somebody in the cloisters of marketing or production. In the current Planet Hong Kong case, and in an earlier instance, I learned of the book’s fate only because I inquired. Who knows when I would have been told?

Nobody likes to give bad news, and university press staff members are unlikely to be flint-hearted business people. Editors are affable and solicitous; I’ve found them good company. They work long and hard on often fruitless projects: proposals that never turn into manuscripts; manuscripts that can’t get through the vetting process; manuscripts that fall hors de combat in editorial meetings.

And academic writers are almost sadistically inconsiderate. Once professors get their book contract, they behave like their students, trotting out excuses that they laugh about in the faculty pub. They ignore deadlines, word counts, permissions—in sum, everything they signed the contract to honor. Yet these antics are tolerated with remarkably good humor. If university book editors had a taste for blood, they’d be trade book editors. Or agents.

More broadly, it seems to me, university presses are under unique pressures. The good side is that they are a business that can’t go out of business. Even in hard times like these, a university press is unlikely to be shuttered. The blow in prestige and faculty morale would be severe. So most presses limp along. Since most of their costs are bound up in salaries, wages, and benefits, the only area that can feasibly be trimmed is marketing.

Furthermore, and too few young scholars realize this, every press plays a crucial role in the tenuring process. A humanities professor teaching in most universities and many colleges typically needs to publish at least one through-written book to support a case for tenure. There is thus a vast demand that some entity publish said books. The problem is that an academic can deftly write a book that virtually no one wants to read, let alone buy. So university presses are, in effect, subsidizing the tenure process.

Seen from this angle, university publishing is a system of reciprocal altruism. The University of West Overshoe Press publishes Professor Smith’s book on cultural resistance in Girl Scout parade floats. Professor Smith is thereby on his way to tenure at his school, the University of Rising Damp. At the same time, the URD Press publishes Professor Jones’ book on sexual transgression in Futurama. Professor Jones resides at Shattered Tibia State, whose press has just accepted a manuscript (on Wittgenstein’s use of prepositions in the Tractatus) from Professor Johnson. . . who teaches at the University of West Overshoe. I’ve abbreviated the cycle, but you can see that eventually, like the spirochete in Professor Pangloss’s song in Bernstein’s Candide, everything circles around. Any one university press is supporting employment at other universities.

So I’m entirely in sympathy with university presses. And the process, eccentric though it sometimes seems, can produce good books. But presses need to deal more straightforwardly and promptly with writers when a book’s fate has been decided. Jim Cortada is right. They never tell you that. But they should, and pronto. For then you can make plans.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0

Shaolin Soccer.

The lesson for young scholars is simple. Expect that your book will go out of print. Some books will pass over to print-on-demand or digital versions, but it doesn’t hurt to expect the worst. And a book can go out of print surprisingly fast. (The original British edition of my book on Ozu lasted only about two years.) You may learn of your work’s passing by accident, as I did, or through more direct notification, but you should think about your options.

You can simply let it go, accepting the press’s rationale that your book will remain available in libraries around the world for decades. Or you can wait for Google or Amazon to get around to digitizing your work.

Yet an out-of-print book is like a child limping home after a few rough encounters with the world. You might feel duty-bound to take care of it somehow. How?

First step in salvage is to make sure pre-print materials have not been destroyed. Most contracts require that these be returned to you if you regain the rights, but publishers, speedy in so little else, can dump physical production materials in the blink of an eye. In the old days, those materials usually consisted of rolls of thick celluloid, three or four feet wide and very long, on which the pages were printed like panels on a vast comic strip. (Several of these monsters lie pod-like in my basement.) But now most books are stored on computer files, often as PDFs. Copies of those should be returned to you.

Until recently, resuscitating your book came down to trying to find another publisher. I’ve had luck with this tactic only once, with The Cinema of Eisenstein—first published by The Syndics in 1994, yanked out of print in the early 2000s, brought back by Routledge in 2005. Republishing was always rare and is now nearly nonexistent; presses can’t afford to bring out a book that may have saturated its market.

Now, though, there’s another way to revive your sickly child.

For some years I’ve argued that most “tenure books” should be published only in digital form. But university presses have been reluctant to try such an idea, since an online book might not satisfy tenure committees. The best plan would be for some well-respected university press to lock in a vetting process for online publication as rigorous as any for print books. It seems that the University of Michigan Press has begun to do this. Once the model proves its value, and once problems of piracy are solved, the practice could catch on fast. For many books I own, I’d be happy to have PDF files on my computer. There should be big cost savings and, we hope, lower purchase prices—maybe even through selling separate chapters. Like music CDs, many books have only a few chapters you want. We can look forward to the iTune-izing of academic writing.

Yet if university presses need to be cautious about online publishing, the individual scholar doesn’t. The tactic is simple: Plan to put your out-of-print books on the Web.

Some authors may prefer to take existing PDF files or make new ones from the book’s pages, and add a fresh introduction. That’s essentially what Marcus Nornes and his colleagues helped me do with Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. We also tipped in new color images.

The alternative is to revise your book and post a second edition online. It’s a lot of work, but then you could probably charge something for it.

As for Planet Hong Kong, I’m still mulling my next step. Perhaps a publisher will be interested in a new edition, revised, corrected, and updated. Alternatively, I might prepare Planet Hong Kong for downloading on this site. Unlike the original, it could have color illustrations. I have to say that I find this option intriguing.

If you want a used copy of the old edition of PHK, about a dozen are available here. Once dealers learn it’s out of print, they may raise their prices. In any event, I hope to bring the book back in some form. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

PTU.

American (Movie) Madness

Grover Crisp and Lea Jacobs outside the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

DB here, again:

He holds sway over thousands of movies and the transfer of hundreds of DVDs. At home he has a high-definition set, but he gets local channels on a rabbit-ears antenna. If that isn’t a working definition of a Film Person, I don’t know what is.

Over the years our UW Film Studies area has hosted many visiting Film Persons, including archivists Chris Horak, Mike Pogorzelski, Joe Lindner, Schawn Belston, and Paolo Cherchi Usai. (1) Being a department centrally interested in film history, we’re eager to screen recent restorations and learn the ins and outs of film archivery.

This year our Cinematheque screened several Sony/ Columbia restorations, running the gamut from Anatomy of a Murder to The Burglar. We wound up our series, and our season, with a stunning print of Frank Capra’s American Madness (1932). To conclude things with a bang, Lea Jacobs, Karin Kolb, and Jeff Smith brought Grover Crisp, Sony’s Senior Vice President of Asset Management, Film Restoration, and Digital Mastering.

Kristin and I had met Grover at the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, and after hearing him introduce some restorations, we knew he had to come to Madison. It was a Bologna screening of American Madness that convinced me that we had to show this sparkling print on our campus. Fortunately for us, Grover squeezed a Madison visit into his schedule and suffered the caprices of American Airlines’ delays. We had about two days of his company.

It was a great learning experience. On Thursday 8 May he addressed our colloquium, where he showed two shorts: a 1933 Screen Snapshots installment explaining the process of motion picture production, from script to final product, and a trim 75-second short by his colleague Michael Friend tracing the evolution of filmmaking technology. On Friday Grover introduced American Madness and took questions.

Just a note about terminology: Archives engage in both film preservation and film restoration. Preservation means, as you’d think, saving films for the future. This involves maintaining the materials (prints, negatives, camera material, sound tracks) in surroundings that minimize harm and deterioration. Restoration demands more resources. It involves trying to create an authoritative version of the film as it existed in some earlier point in history. But that’s a complicated matter, as we’ll see.

Archives and assets

Grover brings a Film Person’s sensitivity to the mission of film preservation. What does that mean? For one thing, he takes the long perspective. Film archivists think about how to store and maintain films for decades, even hundreds of years. In an industry geared to short-term cycles, booms and busts and jagged demand curves, a commercial archivist like Grover, or Schawn of Fox, has to reconcile traditional museum standards with market demands, strategic release considerations, and current studio policies. In short, he has to think both about saving the film for a century and about hitting a DVD street date.

Grover explained his obligations at Sony Pictures Entertainment. He manages all film and television materials. That means preserving everything for any future use and restoring some items for video and theatrical screening. It also means that he keeps abreast of current TV and film productions. This gives him a chance to “embed archival needs” into production and postproduction processes. For example, from 1991 to the present, YCM separation masters are prepared for every film. (2) And today, when a film is finished and output digitally onto a negative for release prints, another negative is assembled from the camera negative, the most pristine source, and that goes into cold storage.

Grover supervises a staff of about twenty-five people, six of whom are overseeing film laboratory and audio work full-time. Unlike other studio archives, Sony does not hand off preservation tasks to outside companies. Being a Film Person, Grover asks that for films a new negative be created, and fresh screening prints be prepared.

What impelled a big company like Sony to invest so much in preservation and restoration? Grover explained that the rise of home video taught most studios that their libraries had some value. In particular, executives were impressed by Ted Turner’s 1986 purchase of MGM for its library, which he could recycle endlessly on TBS. They realized that the libraries were genuine assets. Old movies enhanced the firm’s value (if it were to be sold, as many were in those days) and could be exploited through new media platforms, like cable.

The arrival of DVD made all the studios return to their libraries to make high-quality versions of their top titles. Now the high-definition format of Blu-ray will re-start restoration because of the leap in quality it offers.

Sony moved early, partly because it understood new media. When Sony bought Columbia Pictures in 1989, the Japanese executives envisioned a synergy between Sony’s hardware and a movie studio’s software. “One of the first things they asked,” Grover recalls, “was, ‘What’s the condition of the library?’” Soon afterward, Sony set up the first systematic collaboration between studio archivists and museum-based archivists. The Sony Pictures Film Preservation Committee included archivists from Eastman House, the Library of Congress, UCLA, MoMA, the Academy, and other institutions. In addition, Grover modeled Sony’s restoration policies on the exemplary work of legendary UCLA archivist Bob Gitt (whose work on sound restoration we’ve already saluted in another entry).

Digital restoration has been part of the Sony program. The 1997 restoration of Capra’s Matinee Idol (1927), from a Cinémathèque Française print, was the first live-action high-definition restoration from any studio.

Sony holds between 3600 and 5000 titles. It’s impossible to be more precise at this point because in hundreds of cases the rights situation is uncertain. But of the core library, about half to two-thirds of the films are restored. Crisp’s team is at work on about 200 titles at any moment! Many more are restored than warrant DVD release, but they may be available On Demand and via TCM, which has recently acquired cablecast rights to several older Columbia titles.

Restore, yes! But what, and how?

We’re grateful for preservation, but for cinephiles, restoration holds a special thrill. A “restored” Intolerance or Napoleon or von Sternberg movie gets us salivating. This year Cannes ran nine restorations on its program.

But what is a restoration?

We expect that a restoration will provide a film with a better-quality image or soundtrack than we’ve had so far. We often expect as well that a restoration will provide a more complete version of the title. Yet there are problems with both expectations.

First, who’s to say what the quality of the original is? Grover encountered this difficulty in restoring Funny Girl. It was released in the classic Technicolor dye-transfer process, usually considered the gold standard for color cinematography. He assembled five original Technicolor prints and all of them looked different. It turns out that Technicolor prints varied quite a bit. (3) The kicker was that Grover couldn’t make the new dye-transfer 35mm print of Funny Girl match any of these reference prints. That didn’t stop it looking fabulous when it premiered in LA.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

What about restoration that adds footage to an existing version of a movie? My previous blog entry mentioned an example, the wild and crazy Nerven (1919), to be issued on DVD by the Munich Film Museum. Stefan Drössler, Munich’s curator, has done a remarkable job of incorporating new footage into the longest version of Nerven to date. (The new material includes “living intertitles,” in which actors drape themselves around gigantic letters.) But Nerven remains incomplete, lacking about a third of its original material.

Moreover, it’s possible to “over-restore” a film. That is, by adding footage culled from many versions, the restorer may be creating an expanded version that nobody actually saw.

Original version? What does that mean? Paolo Cherchi Usai has reflected on this at length. (4) Is the original what the film was like on initial release? This is tricky nowadays for new titles, because as Grover pointed out, most films are “initially released” in several versions. Since Hollywood filmmaking began, different versions have been made for the domestic and the overseas markets, and often the overseas versions are longer. Sometimes a film opens locally or at a film festival and then is modified for release. Major films by Hou Hsiao-hsien and Wong Kar-wai have played Cannes in versions longer than circulated later.

Now suppose that the film was modified by producers or censors for its initial release somewhere. If you can determine the filmmaker’s wishes, should you restore the film to what she or he wanted it to be? That flouts the historical principle of getting back to what people actually saw. Consider the shape-shifting Blade Runner. Only now, twenty-five years after its release, has the U. S. theatrical version appeared on video.

Or what do we do when a filmmaker, after the release, decides that the film needs to be changed? Late in life, Henry James felt the urge to rewrite many of his novels, and the revised versions reflect his mature sense of what he wanted his oeuvre to be. Why can’t a filmmaker decide to recast an older film? Such was the case with Apocalypse Now Redux and Ashes of Time Redux. Since the later version represents the artist’s latest viewpoint, should that be the authoritative version?

Grover encountered a variant of this problem when he invited one cinematographer to help restore a film. The cinematographer’s own aesthetic and approach to his work had evolved over the years, so he started to tweak things in a way that was taking the look of the film to a level much different than the original achievement. Grover had to steer him back to respecting the film’s original look.

On the brighter side: Grover brought in master cinematographer Jack Cardiff to advise on the restoration of A Matter of Life and Death. Cardiff said that one scene needed a “more lemony” cast. Grover tried, but each time Cardiff said it wasn’t right. Finally, Grover confessed that he just couldn’t get that lemony look. Cardiff nodded. “Neither could I.”

Grover offers this nugget of wisdom: It is almost impossible to get an older film to look the way it does when it was originally released. The color will never look as it did, nor will sound sound the way it did. Film stocks have changed, printing processes have changed, technology in general has changed. Every version is an approximation, though some approximations may be better than others. Take consolation in the fact that even when the movie was in circulation, it may have already existed in multiple versions.

What do consumers want?

All archivists explain that compromises enter into the preservation process down the line. One of the revelations of Grover Crisp’s visit was the awareness of just how many of these compromises come into play, and how some of them are tied to what DVD buyers expect.

Many films from Hollywood’s studio era are soft, low-contrast, and grainy. Project a 1930s nitrate copy today, and though it will be gorgeous, it’s likely to look surprisingly unsharp. Things apparently didn’t improve when safety stock came along in the late 1940s; projectionists complained that those prints were even softer and harder to focus than nitrate ones. As recently as the 1970s, films were not as crisp as we’d like to think. I’ve examined the first two parts of The Godfather on IB Tech 35mm originals, and though they look sharp on a flatbed viewer, in projection the grains swarm across the screen like beetles. (I should add that many of today’s films also look mushy and grainy in the release prints I see at my local.)

But I think that DVD cultivated a taste for hard-edged images, perhaps in the way that music CDs cultivated a taste for brittle, vacuum-packed sound. It’s not surprising, then, that video aficionados are often startled when a DVD release of a classic movie looks far from clean. This is not always attributable to a film’s not being cleaned up to the fullest extent the technology allows. Some films are inherently grainy, gritty, or soft-looking. With the advent of Blu-ray and HD imagery for the home, those films’ look is often mistaken for problems with the transfer, or signs that the distributor didn’t care enough to spend the money to thoroughly make it new. “New” in this case means contemporary.

So there are compromises, according to Grover, that the studios are having to deal with:

What do do about a film that is really grainy? Do you remove the grain, reduce the grain, leave the grain alone? Everyone seems to have a different answer, and it often puts the distributor in a difficult situation. These are questions that will be answered over time, as the consumer gets used to seeing images in HD that truly represent the way a film looks.

Another compromise involves sound. “Now you’re getting to an ethical area,” Grover remarks. In restoring early sound movies, Sony removes only clicks, pops, and scratchy noises (while still keeping the original, faults and all, as a reference). Sound problems are compounded in films from the early 1950s. Many releases at that time were shot in a widescreen process but retained monaural sound. Yet avid DVD buyers want multitrack versions to feed their home theatres. “If it’s not 5.1, we get complaints.” So Grover’s engineers “upmix” mono, as well as two-channel stereo, to 5.1—though they strive to keep the 5.1 minimal and retain as much authenticity as possible. Not on every film, of course: often the original mono track is included on the DVD.

On the positive side, Sony held the original tracks for Tommy (1975), originally released in Quintaphonic. (Old-timers will remember that audiophiles were urged to upgrade to this, and some LPs were released in that format.) Grover was pleased that he could replicate the theatrical version’s 5-channel mix on the DVD. (More details here.)

Now for a hobby horse of mine. The 1950s-1960s standards for multichannel sound were not those of today’s theatres. Today’s filmmakers funnel important dialogue through the front central speaker. But in multi-track CinemaScope and other widescreen formats, dialogue was spread to the left and right speakers as well, and these were behind the screen. That meant that a character standing on screen left was heard from that spot as well. (Remember, these screens might be seventy feet across.) Long ago Kristin and I saw an original 70mm release print of Exodus (shot in Super Panavision) in a big roadshow house in Paris. The ping-pong effect of the conversations between Ralph Richardson and Eva Marie Saint was fascinating.

Today, however, it might be distracting. In a home theatre, where discrete tracks present sound from offscreen left or right, it would seem downright weird. Although Grover didn’t comment on this, it’s clear that the big-screen classics from the magnetic-track era are remixed for DVD to suit current theatrical and home-video standards. This makes it very difficult for researchers to study the aesthetics of sound design from that period. Even if you visit an archive, that institution almost certainly isn’t able to project the film in a multi-channel version. (5) Is it too late to ask DVD producers to replicate, on a second soundtrack, the original channel layout? This would be a big favor to the academic study of the history of sound, and some home-theatre enthusiasts might develop a taste for the old-fashioned sonic field.

Last questions

Q: Do Grover and his colleagues take notice of online chat about DVD releases?

A: Yes, because it’s important to know what many participants in those conversations want from a film’s release, and they may also know things (from a hardcore fan’s pespective) about a film that is useful to know. Grover’s staff members can learn about missing scenes and other variant prints. But sometimes the Net writers are working from incomplete information and can get things wrong. A fan fervently announced that one word was intelligible in the “original” version of a film but not on the DVD. Yet the theatrical release version muffled the word. It turns out that the word was audible in a remixed TV version, which the fan had used as reference. Likewise, one critic who found the color on the Man for All Seasons Special Edition DVD too vibrant was evidently using a VHS version as the reference point. (For what it’s worth, the color in the Man for All Seasons theatrical release I saw was extremely vivid.) And Grover and his colleagues never intervene in the online debates.

Q: Why do DVDs seem different from projected prints—often much sharper?

A: An original film frame, in camera negative, has more resolution than can be captured in a print. Most prints are a generation or two past the material that a DVD transfer uses, so they gain a certain softness. Granted, however, in making high-definition video masters sometimes the tools to sharpen and de-grain the image are overused.

In addition, it’s generally a good idea to get your home video display calibrated. Most home displays are way too bright, sometimes brighter than a theatre screen. If you darkened the room and had the display dialed down, DVDs would look more film-like.

Q: When will we get the Boetticher westerns?

A: It’s the most frequent question Grover gets asked. Soon, soon: A boxed set of restored titles is on the way.

Q: And what about all the Capra titles?

A: Sony plans to restore each of them. Columbia struck many prints of them, and so there is some negative wear. Some negatives no longer exist. On one title, Say It with Sables (1928), Sony has neither negative nor prints.

There’s a too-good-to-be-true backstory here. Capra had a ranch in Pomona, which upon his death was bequeathed to Pomona State University. After some years, people found in a locked stable his private collection of prints struck in 1939. The cache included Lost Horizon, You Can’t Take It with You, It Happened One Night, and the best-quality print of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington Grover had yet seen. There were also photographs Capra had shot of premieres and vacations. Thanks to the good offices of Frank Capra, Jr., Sony acquired the prints and used them in its restorations.

As for American Madness, Grover called it a “training film” for later Capra productions. The theme of faith in the little man, manifested in a bank run that tests a humane banker’s alliances in the community, points ahead to It’s a Wonderful Life and other films. Sony holds a complete soundtrack and a nearly complete original negative. UCLA held a complete nitrate print donated by the Los Angeles Parks and Recreation Department; evidently the film was screened in parks as public entertainment. That print wasn’t in good condition, but it allowed Grover’s team to fill out certain scenes. The nitrate print’s footage is noticeably lighter and grainier in a few places. American Madness wasn’t a digital restoration, but if it were done today Grover would probably use CGI to blend in the alien footage.

Talkies, with a vengeance

It was fine to see the film again; its brisk inventiveness held up. The gleaming and geometrical images of the opening, which acquaint us with the daily routine of opening the bank vault, might have come out of Metropolis. One helter-skelter montage sequence, complete with canted framings and chiaroscuro lighting, looks forward to Slavko Vorkapich’s delirious contributions to Mr. Smith and Meet John Doe.

The tactics of depth composition that we find in many 1930s movies reappear here, and the illumination has dashes of noir.

I especially like the dynamic pans that carry Walter Huston and Pat O’Brien in and out of the main office; I suspect that they’re cut together faster and faster as the climax gets near. And the huge set of the bank lobby, publicized at the time as the biggest set yet built on the Columbia lot, remains not only impressive but functional. It establishes a cogent geography to which Capra adheres strictly while filming it from a great variety of angles.

But this is not a treat just for the eyes. American Madness flaunts its mastery of emerging talkie technique. The rising action is accentuated by the steady increase in volume of the growing crowd in the bank lobby. The clerks’ scattershot morning chat in the vault is captured in microphone distances and auditory textures that suggest a hollow, sealed-off space. Hawks’ rapid-fire patter in Twentieth Century (1934) has an antecedent here, and at the same studio. The actors speak at a terrific clip, scarcely pausing between lines, and sometimes the dialogue overlaps. We even get competing lines, two or more speeches rattled off at once. (And did Hawks get the idea for His Girl Friday’s variants on telephone chatter from O’Brien working the receivers at the climax?)

In films like this, American movies talk American. Consequently, I’m inclined to regard as an in-joke the glimpse we get of a marquee that’s advertising another Columbia picture: Hollywood Speaks.

Thanks to Grover and Sony Pictures Entertainment for a wonderful series and an enlightening brace of talks. American Madness is available on the DVD set The Premiere Frank Capra Collection.

(1) Chris Horak has been head archivist at George Eastman House, the Munich Film Museum, Universal, and the Hollywood Museum; he’s now Director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive. Mike Pogorzelski is Director of the Film Archive for the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences; Joe Lindner is Preservation Officer there. (Both are former Badgers.) Schawn Belston is Vice President of Asset Management and Film Preservation at Twentieth Century Fox. Paolo Cherchi Usai is Director of ScreenSound Australia, the national archive, and director of the recent film Passio. Kristin interviewed Mike and Schawn for this blog entry.

(2) YCM separation masters are made by copying a color film onto three black-and-white films. Thanks to filtering, these preserve color luminance at the different values of yellow, cyan, and magenta. Since these monochrome versions are not as susceptible to fading, they can be used for archival preservation. Combined, they can recreate the original color image.

(3) This confirms my impression when I’ve seen different Technicolor prints of the same title. You sometimes get this effect with a composite print, in which the color values change from reel to reel. Anecdotally, I’ve heard that Technicolor staff in the studio days would sort reels according to their dominant color (“That’s the yellow pile over there”).

(4) See Chapter 7 of Silent Cinema: An Introduction (London: British Film Institute, 2000). This book, incidentally, is a good introduction to the sheer fun of archive work. Others communicating the same enthusiasm are Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec, This Film Is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film (Brussels: FIAF, 2002) and Dan Nissen et al., eds., Preserve Then Show (Copenhagen: Danish Film Institute, 2002).

(5) This problem renders the activities of Britain’s National Media Museum in Bradford all the more important. There you can see classic films in a great many formats and sound arrays.

American Madness.

15 June: Thanks to Kent Jones for correcting a name slip.

19 June: Breaking News: Grover has just been promoted to Senior Vice President for asset management, film restoration, and digital mastering. Nice timing; wish we could say our blog put him over the top, butVariety explains that it was good old-fashioned talent. Congratulations to Grover!

Snapshots and soundbites

Boardman’s Art Theatre, two blocks from the Virginia Theatre, Champaign, Illinois.

DB here:

As you may surmise, a hell of a time was had by all at last week’s Ebertfest. In the sessions I moderated, I was often so busy listening and thinking about my next question that I didn’t have time to write down all the aperçus that spilled forth from the guests. But here are some soundbites, mixed with pix.

Jeff Nichols, director of Shotgun Stories: “I managed to make a 90-minute movie that feels 2 ½ hours long.”

Jeff Nichols, John Peterson (The Real Dirt on Farmer John), Eran Kolirin (The Band’s Visit), Timothy Spall (Hamlet).

Bill Forsyth on his early work: “I made films about teenagers because they were cheap to hire.”

Christine Lahti (Swing Shift, Running on Empty, Jack & Bobby, Amerika) and Bill Forsyth, reunited for the screening of Housekeeping.

Why so much multiframe imagery in Hulk? “In those notes you get from studio people,” Ang Lee explained, “they always want more and faster. So I decided to give it to them.”

Ang Lee (Hulk) and unidentified admirer.

Barry Avrich asked Suzanne Pleshette how she had survived so long in the industry. Suzanne: “I don’t have a gag reflex.”

Barry Avrich (The Last Mogul, Satisfaction, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, and the book Selling the Sizzle).

Paul Schrader: Theatrical screening is dead. “The multiplexes look like mortuaries.”

Tom DiCillo: “Going to a film is a religious experience. . . . When you see it on a computer screen, fuck it.”

Tom DiCillo (Delirious) and Timothy Spall.

Paul Schrader: “When I started, there was a crisis of content. Nobody knew what a movie should be about. So we had films with sex and violence and anti-heroes. But now we have a crisis of form. How long should a movie be? How big should the screen be? What is this thing called movies?”

Paul Schrader (Mishima) and Hannah Fisher (Dubai International Film Festival).

“What part of this is directing?” Tom DiCillo, reflecting on the fact that it took six years to set up Delirious and he spent only 25 days behind the camera.

Tarsem Singh: “I’ve been an atheist since I was nine. I’ve never used any intoxicant—drugs or liquor or whatever. But I don’t like to associate with nondrinkers: they’re either religious or reformed alcoholics.”

Mary Corliss (Film Comment) and Richard Corliss (Time).

Joey Pantoliano (The Matrix, Memento, The Sopranos, Canvas, and book Who’s Sorry Now) with unidentified admirer.

Michael Barker (Sony Pictures Classics).

Eiko Ishioka: “When Paul asked me what I thought about Mishima, I said, ‘I don’t like him.’ He said, ‘Perfect!'”

Eiko Ishioka (Mishima, The Cell, The Fall), multimedia artist.

The Ebertfest Team

Chaz Ebert.

Mary Susan Britt.

James Bond, projectionist, and Nate Kohn, Festival Director.

See you here next year? Jim Emerson (scanners, Rogerebert.com) is counting the hours.

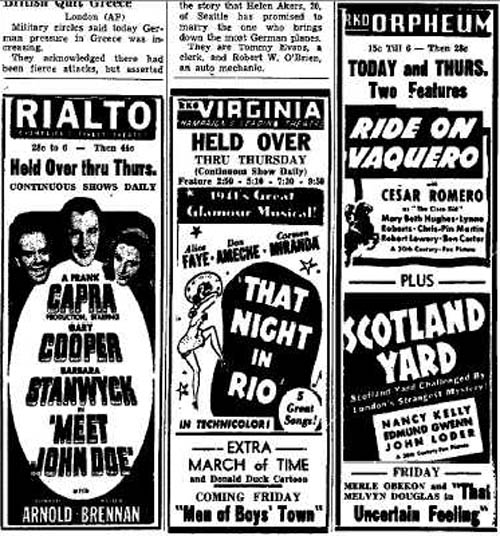

Bonus feature: What you would have been able to see in Urbana-Champaign 16 April 1941.

A behemoth from the Dead Zone

DB here:

The first quarter of the year is the biggest slump time for movie theatres. (1) Holiday fatigue, thin budgets, bad weather, the Super Bowl, and the distractions of the awards season depress admissions. If people go to the movies, they tend to catch up on Oscar nominees, and studios don’t want to release high-end films that might suffer from the competition. But screens need fresh product every week, so most of what gets released at this time of the year might charitably be called second-tier.

Ambitious filmmakers fight to keep out of this zone of death. You could argue that the January release slot of Idiocracy told Mike Judge exactly what Fox thought of that ripe exercise in misanthropy. Zodiac, one of the best films of 2007, opened on 1 March, and even ecstatic reviews couldn’t push it toward Oscar nominations. You can imagine what chances for success Columbia has assigned to Vantage Point (a 22 February bow). [But see my 4 Feb. PPPS below.]

Yet this is a flush period for those of us who like to explore low-budget genre pieces. I have to admit I enjoy checking on those quickie action fests and romantic comedies that float up early in the year. They’re today’s equivalent of the old studios’ program pictures, those routine releases that allowed theatres to change bills often. In their budgets, relative to blockbusters, today’s program pix are often the modern equivalent of the studios’ B films.

More important, these winter orphans are often more experimental, imaginative, and peculiar than the summer blockbusters. On low budgets, people take chances. Some examples, not all good but still intriguing, would be Wild Things (1998), Dark City (1998), Romeo Must Die (2000), Reindeer Games (2000), Monkeybone (2001), Equilibrium (2002), Spun (2003), Torque (2004), Butterfly Effect (2004), Constantine (2005), Running Scared (2006), Crank (2006), and Smokin’ Aces (2007). The mutant B can be found in other seasons too—one of my favorites in this vein, Cellular (2004), was released in September—but they’re abundant in the year’s early months.

By all odds, Cloverfield ought to have been another low-end release. A monster movie with unknown players, running a spare 72 minutes sans credits, budgeted at a reputed $25 million, it’s a paradigm of the winter throwaway. Except that it pulled in $46 million over a four-day weekend and became the highest-grossing film (in unadjusted dollars) ever to be released in January. Here the B in “B-movie” stands for Blockbuster.

I enjoyed Cloverfield. It starts with a sharp premise, but as ever, execution is everything. I see it as a nifty digital update of some classic Hollywood conventions. Needless to say, many spoilers loom ahead.

If you find this tape, you probably know more about this than I do

Everybody knows by now that Cloverfield is essentially Godzilla Meets Handicam. A covey of twentysomethings are partying when a monster attacks Manhattan, and they try to escape. One, Rob, gets a phone call from his off-again lover Beth, who’s trapped in a high-rise. He vows to rescue her. He brings along some friends, one of whom documents their search with a video camera. It’s a shooting-gallery plot. One by one, the characters are eliminated until we’re down to two, and then. . . .

Cloverfield exemplifies what narrative theorists call restricted narration. (Kristin and I discuss this in Chapter 3 of Film Art.) In the narrowest case of restricted narration, the film confines the audience’s range of knowledge to what one character knows. Alternatively, as when the characters are clustered in the same space, we’re restricted to what they collectively know. In other words, you deny the viewer a wider-ranging body of story information. By contrast, the usual Godzilla installment is presented from an omniscient perspective, skipping among scenes of scientists, journalists, government officials, Godzilla’s free-range ramblings, and other lines of action. Instead, Cloverfield imagines what Godzilla’s attack would look and feel like on the ground, as observed by one group of victims.

Horror and science fiction films have used both unrestricted and restricted narration. A film like Cat People (1942) crosscuts what happens to Irena (the putative monster) with scenes involving other characters. Jurassic Park and The Host likewise trace out several plot strands among a variety of characters. The advantage of giving the audience so much information is that it can feel apprehension and suspense about what the characters don’t know is happening. Our superior knowledge can make us worry about those poor victims oblivious to their fate.

But these genres have relied on restricted narration as well. Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956) is a good example; we are at Miles’s side in almost every scene, learning of the gradual takeover of his town as he does. Night of the Living Dead (1968), Signs (2002), and War of the Worlds (2005) do much the same with a confined group, attaching us to one or the other momentarily but never straying from their situation.

The advantages of restricted narration are pretty apparent. You can build up uncertainty and suspense if we know no more than the character(s) being attacked by a monster. You can also delay full revelation of the creature, a big deal in these genres, by giving us only the glimpses of it that our characters get. Arguably as well, by focusing on the characters’ responses to their peril, you have a chance to build audience involvement. We can feel empathy and loss if we’ve come to know the people more intimately than we know the anonymous hordes stomped by Godzilla. Finally, if you need to give more wide-ranging information about what’s happening outside the characters’ immediate situation, you can always have them encounter newspaper reports, radio bulletins, and TV coverage of action occurring elsewhere.

People sometimes think that theoretical distinctions like this overintellectualize things. Do filmmakers really think along these lines? Yes. Matt Reeves, the director of Cloverfield, remarks:

The point of view was so restricted, it felt really fresh. It was one of the things that attracted me [to this project]. You are with this group of people and then this event happens and they do their best to understand it and survive it, and that’s all they know.

For your eyes only

Restricted narration doesn’t demand optical point-of-view shots. There aren’t that many in Invasion of the Body Snatchers or the other examples I’ve indicated. Still, for quite a while and across a range of genres, filmmakers have imagined entire films recording a character’s optical/ auditory experience directly, in “first-person,” so to speak.

Again, it’s useful to recognize two variants of this narrational strategy. One we can call immediate—experiencing the action as if we stood in the character’s shoes. In the late 1920s, the great documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens tried to make what he called his I-film, which would record exactly what a character saw when riding a bike, drinking a glass of beer, and the like. He was dismayed to find that bouncing and swiveling the camera as if it were a human eye ignored the fact that in real life, our perceptual systems correct for the instabilities of sensation. Ivens abandoned the project, but evidently he couldn’t get the notion out of his head; he called his autobiography The Camera and I. (2)

Hollywood’s most strict and most notorious example of directly subjective narration is Robert Montgomery’s Lady in the Lake (1947). Its strangeness reminds us of some inherent challenges in this approach. How do you show the viewer what your protagonist looks like? (Have him pass in front of mirrors.) How do you skip over the boring bits? (Have your hero knocked unconscious from time to time.) How do you hide the inevitable cuts? (Try your best.) Even Montgomery had to treat the subjective sequences as long flashbacks, sandwiched within scenes of the hero in his office in the present telling us what he did next.

Because of these problems, a sustained first-person immediate narration is pretty rare. The best compromise, exploited by Hitchcock in many pictures and especially in Rear Window (1954), is to confine us to a single character’s experience by alternating “objective” shots of the character’s action with optical point-of-view shots of what s/he sees.

What I’m calling immediate optical point of view is just that: sight (and sounds) picked up directly, without a recording mechanism between the story action and the character’s experience. But we can also have mediated first-person point of view. The character uses a recording technology to give us the story events.

In a brilliant essay on the documentary Kon-Tiki (1950), André Bazin shows that our knowledge of how Thor Heyerdahl filmed his raft voyage lends an unparalleled authenticity to the action. Heyerdahl and his crew weren’t experienced photographers and seem to have taken along the 16mm camera as an afterthought, but the very amateurishness of the enterprise guaranteed its realism. Its imperfections, often the result of hazardous conditions, were themselves testimony to the adventure. When the men had to fight storms, they had no time to film; so Bazin is able to argue, with his inimitable sense of paradox, that the absence of footage during the storm is further proof of the event. If we were given such footage, we might wonder if it was staged afterward.

How much more moving is this flotsam, snatched from the tempest, than would have been the faultless and complete report offered by an organized film. . . . The missing documents are the negative imprints of the expedition. (3)

What about fictional events? In the 1960s we started to see fiction films that presented themselves as recordings of the events as the camera operator experienced them. One early example is Stanton Kaye’s Georg (1964). The first shot follows some infantrymen into battle, but then the framing wobbles and the camera falls to earth. We see a tipped angle on a fallen solider and another infantryman approaches.

He bends toward us; the frame starts to wobble and we are lifted up. On the soundtrack we hear, “I found my camera then.”

The emergence of portable equipment and cinema-verite documentary seems to have pushed filmmakers to pursue this narrational mode in fiction. One result was the pseudo-documentary, which usually doesn’t present the story as a single person’s experience but rather as a compilation of first-person observations. Peter Watkins’ The War Game (1967) presents itself as a documentary shot during a nuclear war, and it contains many of the visual devices that would come to be associated with the mediated format—not only the flailing camera but the face-on interview and the chaotic presentation of violent action. There’s also the pseudo-memoir film, pioneered in David Holzman’s Diary (1967). Later examples of the pseudo-documentary are Norman Mailer’s Maidstone (1971) and the combat movie 84 Charlie MoPic (1989). (4)

As lightweight 16mm cameras made filming easier, directors adapted that look and feel to fictional storytelling. The arrival of ultra-portable digital cameras and cellphones has launched a similar cycle. Brian DePalma’s Redacted (2007), yet another war film, has exploited the technology for docudrama. A digital equivalent of David Holzman’s Diary, apart from Webcam and YouTube material, is Christoffer Boe’s Offscreen (2006), which I discussed here.

Interestingly, Orson Welles pioneered both the immediate and the mediated subjective formats. One of his earliest projects for RKO was an adaptation of Heart of Darkness, in which the camera was to represent the narrator Marlowe’s optical perspective throughout. (5) Welles had more success with the mediated alternative, though in audio form. His “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast mimicked the flow of programming and interrupted it with reports of the aliens’ attack. The device was updated for television in the 1983 drama Special Bulletin.

Sticking to the rules

Cloverfield, then, draws on a tradition of using technologically mediated point-of-view to restrict our knowledge. Like The Blair Witch Project (1999), it does this with a horror tale. But it’s also a Hollywood movie, and it follows the norms of that moviemaking mode. So the task of Reeves, producer J. J. Abrams, and the other creators is to fit the premise of video recording to the demands of classical narrative structure and narration. How is this done?

First, exposition. The film is framed as a government SD video card (watermarked DO NOT DUPLICATE), the remains of a tape recovered from an area “formerly known as Central Park.” This is a modern version of the discovered-manuscript convention familiar from the nineteenth-century novel. When the tape starts, showing Rob with Beth in happy times, its read-out date of April plays the role of an omniscient opening title. In the course of the film, the read-outs (which come and go at strategic moments) will tell us when we’re in the earlier phase of their love affair and when we’re seeing the traumatic events of May.

Likewise, the need for exposition about characters and relationships at the start of the film is given through a basic premise. Jason wants to record Rob’s going-away-party and he presses Rob’s friend Hud into service as the cameraman. Off the bat, Hud picks out our main characters in video portraits addressed to Rob. What follows indicates that Hud will be amazingly prescient: His camera dwells on the characters who will be important in the ensuing action.

Next, overall structure. The Cloverfield tape conforms to the overarching principles that Kristin outlines in Storytelling in the New Hollywood and that I restated in The Way Hollywood Tells It. (Another example can be found here.) A 72-minute film won’t have four large-scale parts, most likely two or three. As a first approximation, I think that Cloverfield breaks into:

*A setup lasting about 30 minutes. We are introduced to all the characters before the monster attacks. Our protagonists flee to the bridge, where Jason dies. Near the end of this portion, Rob gets a call from Beth, and he formulates the dual goals of the film: to escape from the creature, and to rescue Beth. Along the way, Hud declares he’s going to record it all: “People are gonna know how it all went down. . . . It’s gonna be important.”

*A development section lasting about 22 minutes. This is principally a series of delays. Rob, Hud, Lily, and Marlena encounter obstacles. Marlena falls by the wayside. They are given a deadline: At 0600 they must meet the last helicopters leaving Manhattan.

*A climax lasting about 20 minutes. The group rescues Beth and meets the choppers, but the one carrying Rob, Hud, and Beth falls afoul of the beast. They crash in Central Park, and Hud is killed, his camera recording his death at the jaws of the monster. Huddled under a bridge, Rob and Beth record a final video testimonial before an explosion cuts them off.

*An epilogue of one shot lasting less than a minute: Rob and Beth in happier times on the Ferris wheel at Coney Island—a shot left over from the earlier use of the tape in April.

Next, local structure and texture. It takes a lot of artifice to make something look this artless. The imagery is rich and vivid, the sharpest home video you ever saw. The sound is pure shock-and-awe, bone-rattling, with a full surround ambience one never finds on a handicam. (6) Moreover, Hud is remarkably lucky in catching the turning points of the action. All the characters’ intimate dramas are captured, and Hud happens to be on hand when the head of Miss Liberty hurtles down the street.

Bazin points out that in fictional films the ellipses are cunning gaps, carefully designed to fulfill narrative ends—not portions left out because of the physical conditions of the shoot. Here the cunning gaps are justified as constrained by the physical circumstances of filming. When Hud doesn’t show something, it’s usually because it’s what the genre considers too gross, so the worst stretches take place in darkness, or offscreen, or strategically shielded by a prop when the camera is set down.

Mostly, though, Hud just shows us the interesting stuff. He turns on the camera just before something big happens, or he captures a disquieting image like that of the empty Central Park carriage.

At least once, the semi-documentary premise does yield something evocative of the Kon-Tiki film. Hud has to leap from one building to another, many stories above the street. He turns the camera on himself: “If this is the last thing you see, then I died.” He hops across, still running the camera, but when a rocket goes off nearby, a sudden cut registers his flinch. For an instant out of sheer reflex, he turned off the camera.

Overall, Hud’s tape respects the flow of classical film style. Unlike the Lady in the Lake approach, the mediated POV format doesn’t have a problem with cuts; any jump or gap is explained as a moment when the operator switched off the camera. Most of Hud’s “in-camera” cuts are conventional ones, skipping over a few inconsequential stretches of time. There are as well plenty of hooks between scenes. (For more on hooks, go here.) Hud says: “I’ll walk in the tunnels.” Cut to characters walking in the tunnels. More interestingly, visible cuts are rare, which again respects the purported conditions of filming. Cloverfield has much longer takes than any recent Hollywood film I know. I counted only about 180 shots, yielding an average of 24 seconds per shot (in a genre in which today’s films average 2-5 seconds per shot).

The digital palimpsest

We could find plenty of other ways in which Cloverfield adapts the handicam premise to the Hollywood storytelling idiom. There are the product placements that just happen to be part of these dim yuppies’ milieu. There are the character types, notably the sultry Marlena and the hero’s weak friend who’s comically a little slow. There’s the developing motif of the to-camera addresses, with Rob and Beth’s final monologues to the camera counterbalancing the party testimonials in the opening. There’s the final romantice exchange: “I love you.” “I love you.” The very last shot even includes a detail that invites us to re-view the entire movie, at the theatre or on DVD. But let me close by noting how some specific features of digital video hardware get used imaginatively.

I’ve already mentioned how the viewfinder date readout allows us to keep the time structure clear. There’s also the use of a night-vision camera feature to light up those spidery parasites shucked off by the big guy. Which scares you more—to glimpse the pinpoint eyes of critters skittering around you in the dark, or to see them up close in a sickly green light?

More teasing is the fact, set up in the first part, that this video is being recorded over an old tape of Rob’s. That’s what turns the opening sequence of Rob and Beth in May into a prologue: the tape wasn’t rewound completely for recording the party. Later, at intervals, fragments of that April footage reappear, apparently through Hud’s inadvertently advancing the tape. The snippets functions as flashbacks, showing Rob and Beth going to Coney Island and juxtaposing their enjoyable day with this horrendous night.

Cleverly, on the tape that’s recording the May disaster something always prepares the audience for the shift. For instance, when Jason hands the camera over, we hear Hud say, “I don’t even know how to work this thing.” Cut to an April shot of Beth on the subway, suggesting that he’s advanced fast forward without shooting. Likewise, when Rob says, “I had a tape in there,” we cut to another April shot of Beth. As a final fillip, the footage taken in May halts before the tape ends, so we get the epilogue showing Rob and Beth on the Ferris wheel in April, emerging like figures in a palimpsest.

No less clever, but also a little poignant, is the use of the fallen-camera convention. It appears once when Beth has to be extricated from her bed. Hud sets the camera down by a concrete block in her bedroom, which conceals her agony. More striking is the shot when the camera, dropped from Hud’s hand, lies in the grass, and the autofocus device oscillates endlessly, straining to hold on his lifeless face.

In sum, the filmmakers have found imaginative ways of fulfilling traditional purposes. They show that the look and feel of digital video can refresh genre conventions and storytelling norms. So why not for the sequel show the behemoth’s attack from still other characters’ perspectives? This would mobilize the current conventions of the narrative replay and the companion film (e.g., Eastwood’s Iwo Jima diptych). Reeves says:

The fun of this movie was that it might not have been the only movie being made that night, there might be another movie! In today’s day and age of people filming their lives on their iPhones and Handycams, uploading it to YouTube. . . .

So the Dead Zone of January through March yields another hopeful monster. What about next month’s Vantage Point? The tagline is: 8 Strangers. 8 Points of View. 1 Truth. Hmmm. . . . Combining the network narrative with Rashomon and a presidential assassination. . . . Bet you video recording is involved . . . . See you there?

PS: At my local multiplex, you’re greeted by a sign: WARNING: CLOVERFIELD MAY INDUCE MOTION SICKNESS. I thought this was just the theatre covering itself, but I’ve learned that no recent movie, not even The Bourne Ultimatum, has had more viewers going giddy and losing their lunch. You can read about the phenomenon here, and Dr. Gupta weighs in here. My gorge can rise when a train jolts, but I had no problems with two viewings of Cloverfield, both from third row center.

Anyhow, it will be perfectly easy to watch on your cellphone. But we should expect to see at least one pirate version shot in a theatre by someone who’s fighting back the Technicolor yawn, giving us more Queasicam than we bargained for.

(1) The only period that rivals this slow winter stretch is mid-August to October, when genre fare gets pushed out to pick up on late summer business. [Added 26 January:] There are, I should add, two desirable weekends in the first quarter, those around Martin Luther King’s birthday and Presidents’ Day. Studios typically aim their highest-profile winter releases (e.g., Black Hawk Down, 2001) for those weekends.

(2) Joris Ivens, The Camera and I (New York: International Publishers, 1969), 42.

(3) André Bazin, “Cinema and Exploration,” What Is Cinema? Vol. 1, trans. and ed. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 162.

(4) Not all pseudodocumentaries present themselves as records of a person’s observation. Milton Moses Ginsberg’s Coming Apart (1969) presents itself as an objective record, by a hidden camera, of a psychiatrist’s dealings with his patients. Like a surveillance camera, it doesn’t purport to embody anybody’s point of view.

(5) Jonathan Rosenbaum, Discovering Orson Welles (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007), 28-48.

(6) For Kevin Martin’s informative account of the film’s polished lighting and high-definition video capture, go here (and scroll down a bit). For discussions of contemporary sound practices in this genre, see William Whittington’s Sound Design in Science Fiction (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2007).

PS: Thanks to Corey Creekmur for correcting two slips in my initial post!

PPS 28 January: Lots of Internet buzz about the film since I wrote this. Thanks to everyone who linked to this post, and special thanks for feedback from John Damer and James Fiumara.

Some people have asked me to comment on the social and cultural implications of Cloverfield’s references to 9/11. At this point I think that genre cinema has dealt more honestly and vividly with the traumas and questioning around this horrendous event than the more portentous serious dramas like United 93, World Trade Center, and the TV show The Road to 9/11.

The two most intriguing post-9/11 films I know are by Spielberg. The War of the Worlds gives a really concrete sense of what a hysterical America under attack might be like, warts and all. (It reminded me of a TV show I saw as a kid, Alas, Babylon (1960), a surprisingly brutal account of nuclear-war panic in suburbia.) Spielberg’s underrated The Terminal reminds us, despite its Frank Capra optimism, that the new Security State is run by bureaucrats with fixed agendas and staffed by overworked people of color, some themselves exiles and immigrants.

I think that Cloverfield adds its own dynamic sense of how easily the entitlement culture of upwardly mobile twentysomethings can be shattered. Genre films carry well-established patterns and triggers for feelings, and a shrewd filmmaker can channel them for comment on current events—as we see in the changing face of Westerns and war films in earlier phases of Hollywood history.

On this point, Cinebeats offers some shrewd responses to criticisms of Cloverfield here.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

Finally: In the new Creative Screenwriting an informative piece (not available online) indicates that the initial logline for Vantage Point on imdb is misleading. Screenwriter Barry Levy planned to present the assassination from seven points of view, but reduced that to six. As for my speculation that video recording/replay would be involved, a production still seems to offer some evidence. Shall we call it the Cloverfield effect? The same issue of CS has a brief piece on the script for Cloverfield.

PPS 30 January: Shan Ding brings me another story about the making of Cloverfield, and Reeves is already in talks for a sequel, says Variety.

PPPS 4 February: A recent story in The Hollywood Reporter offers a nuanced account of how Hollywood is rethinking its first-quarter strategies. Across the last 4-5 years, a few big releases have done fairly well between January and April; a high-end film looks bigger when there is less competition. The author, Steven Zeitchik, suggests that the heavy packing of the May-August period and the need for a strong first weekend are among the factors that will encourage executives to spread releases through the less-trafficked months. I hope, though, that tonier fare won’t crowd out the more edgy, low-end genre pieces that bring me in.

PPPPS 8 February: How often has a wounded Statue of Liberty featured in the apocalyptic scenarios of comics and the movies? Lots, it turns out. Gerry Canavan explains here.