Archive for the 'New media: Technology' Category

New media and old storytelling

DB asks: To what extent has the DVD changed viewing habits and movie storytelling?

As everybody knows, a DVD offers more interactivity than a movie you watch in a multiplex. In a theatre, the movie rolls on, unaffected by anything you may do. But with a DVD you can pause the film, run fast forward, skip to a particular second, shuffle chapters, even play the thing in reverse.

Most minimally, the DVD offers greater convenience. You can halt the film so you can answer a phone call or zip back to replay a bit you might have missed. But some of us wonder if this new interactivity harbors more radical implications. Does the new flexibility of use allow us to experience the film in new ways?

In a mystery film, say there’s a clue at the half-hour mark. In a theatrical screening, we’re pressed forward with no time to ponder it. Watching the film on DVD lets us halt the film, ponder the clue as long as we like, and maybe track patiently back to earlier scenes to test our suspicions about what that clue means. Or suppose you decide to sample the film, browsing through the opening bits of several chapters? More radically, suppose we decide to watch the DVD in reverse? Nothing stops us, and we’d have an experience of the story very different from that of someone who watched the film in the normal order. Doesn’t this all suggest that it’s hard to generalize about what the “ordinary” viewer’s experience of a movie might be nowadays?

Now consider the craft of fictional filmmaking. The movie’s creators make choices about what story information to impart, when to impart it, and how to impart it. They assume that the viewer follows the story in the order mandated by theatrical projection, scene 1, then 2, 3 and onward. Likewise, the pace of uptake is set by the film—no slowing down or speeding up at the viewer’s will. But given the new conditions of digital consumption, these assumptions may be wrong. So shouldn’t the filmmakers take those conditions into account? And more specifically, haven’t some filmmakers already taken them into account? In other words, hasn’t the DVD transformed cinematic storytelling?

This question is important to me. I’ve long argued, along with Kristin, that mainstream US filmmaking, dubbed long ago “classical Hollywood cinema,” has cultivated a sturdy and pervasive tradition of storytelling. (1) That tradition depends on clearly defined characters pursuing well-defined goals. This commitment in turn creates a plot that displays linear cause and effect: In pursuing goals, the protagonist makes one thing happen, and that makes something else happen, which in turn triggers something else. Moreover, the mainstream tradition lays these actions and reactions along a fairly rigid structural layout. And this tradition depends on a system of narration that constantly reiterates the characters’ traits, their goals, important motifs, and the overall circumstances of the action. This is a fairly abstract description, I know; go to my analysis of Mission: Impossible III for a specific example of how the system can work.

But now home video allows our consumption to be highly nonlinear. By skipping or skimming DVD chapters, we may not register the plot or narration as the makers intended. Doesn’t this make hash of goal-directed action, character arcs, and all the other features of classical storytelling? Might we not be moving toward a “post-classical” cinema?

Movie as book

Let’s tackle the question first from the standpoint of the viewer. I think we can get help by recognizing this basic point: The DVD made a movie more like a book.

This sounds odd, because we think of digital media as replacing print. Yet consider the similarities. You can read a book any way you please, skimming or skipping, forward or backward. You can read the chapters, or even the sentences, in any order you choose. You can dwell on a particular page, paragraph, or phrase for as long as you like. You can go back and reread passages you’ve read before, and you can jump ahead to the ending. You can put the book down at a particular point and return to it an hour or a year later; the bookmark is the ultimate pause command.

We tacitly acknowledge the resemblance between the DVD and the book when we call the segments on a DVD its chapters, the list of chapters an index, and the process of composing the DVD its authoring.

With these similarities in mind, we can ask: How many people, on first contact, would sit down to watch a film in a nonlinear way?

My hunch: Just about as many who would buy or borrow a book and then proceed to read it in a nonlinear way. Now we can grant that if you have a nonfiction book in hand, you might pick out certain chapters as more interesting than others and move straight to those. Similarly, with a DVD documentary on penguins, some viewers might want to move straight to the chapter labeled Mating Habits.

With a fictional film, though, we’re much less inclined to graze and browse, just as with a novel. True, we might sample the novel before buying or borrowing it, but I’d bet the portion we’re most likely to sample is the opening chapter. With a fiction film on DVD, some viewers might skip to a chapter opening or two, but I expect that soon they’d settle down to watching the show at the order and pace of a theatrical screening. This is more or less what happens with literary fiction. The person who starts a novel will proceed in linear order in order to follow the story. It’s a revealing phrase: we’re following a path laid down for us, not racing ahead or falling back.

This isn’t to say that all consumers of fiction move at the same pace or read the same way. I’m just indicating that following the mandated order, page by page or shot by shot, is the default that people adhere to in the overwhelming majority of cases.

This suggests that pausing is the most common way we play an interactive role. When reading a book you might call out to your friend and reread a particularly striking description or funny dialogue exchange. When watching a film, you might stop and replay some images to enjoy them again. Another common act is probably quickly “paging back”—rereading or re-viewing a bit that just preceded the pause to remind ourselves of what’s going on at the moment.

Our purpose in starting a book or film at the beginning is to get into the story world and start to think and feel in relation to the information we get about it. But we don’t have to take that as our primary purpose. More extreme acts of “creative” spectatorship are tied to different purposes than learning about the story world. I suppose that teenage boys might well rent 300 when it comes out on DVD and fast-forward looking only for the scenes showing carnage or naked ladies….the same way that my high-school contemporaries rummaged through Terry Southern’s Candy digging out the good parts. (2) But this doesn’t seem to be a radically new way of using any medium, because the purpose—scanning a text for immediate gratification rather than narrative involvement—was common well before DVD.

Of course we students of cinema use the DVD commands in order to study a film, spooling back and forth to analyze it. But that usage isn’t a radical reworking of consumption either. Typically before we start to analyze a movie, we’ve already experienced it in the ordinary beginning-to-end way. Students of literature execute the same sort of back-and-forth moves studying a text that they’ve read before.

Finally, I’d suggest that a highly unorthodox mode of consumption, like setting out to watch a film in reverse at 8x speed, would become quite boring fast. As with so many things in life, just because you can do something doesn’t mean you’d enjoy it.

Speculation 1: The actual uses that people make of DVD interactivity are limited; traditional beginning-to-end consumption is the default.

Speculation 2: Pausing, paging back, and scanning for the good bits suggest that the most frequent DVD interactivity is familiar from other media, particularly books.

Guided interactivity

Let’s now consider things from the side of the creators. Knowing that films are seen on DVD, don’t filmmakers adjust their art and craft to this new medium? Of course they can provide revised versions, or directors’ cuts, along with alternative endings, deleted scenes, and other material that shed light on the film and the production process. But does the DVD format change the very act of conceiving and executing the story presented by the film?

Yes, in certain respects. In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argue that the possibility of rewatching a film with little fuss encourages ambitious filmmakers to “load every rift with ore,” to pack in details that might not be noticed on a single viewing. One of my examples is the 8/2 motif in Magnolia. Likewise, the looping plotlines of Donnie Darko and the reverse-order one of Memento are amenable to being picked apart after several viewings. But before home video, you as a viewer could scrutinize such movies by just going back to the theatre and watching the film over and over, very attentively.

Clumsy as it seems, film nerds of my generation did this. I remember my thrill as a junior in college when I discovered, after rerunning a 16mm print of Citizen Kane on my apartment wall, the snowstorm paperweight that Kane clutches on his deathbed sitting on Susan’s vanity table the night he first meets her. Welles had, as it were, planted this clue for attentive viewers to spot. When we were lucky, we might get a film on a flatbed viewer and go through it reel by reel. Granted, the random-access aspect of DVD allows this sort of micro-analysis to be done much more easily, but it’s not different in kind from rolling up your sleeves and threading up a Films Incorporated print one more time.

I’d add that this sort of scrutiny enriches the film in a very traditional way. Films that sustain this sort of attention, from Buster Keaton silent movies to Hiroshima mon amour and The Silence of the Lambs, long predate the arrival of DVD. Throughout Play Time Tati sprinkled details and gags that reward many viewings. When Paul Thomas Anderson and Christopher Nolan bury details in their films, or when The Simpsons flashes a jokey sign past us, they’re practicing a time-honored strategy of teasing the viewer to return to the work to get something more out of it. Having the DVD at your disposal makes it easier to find half-hidden motifs, jokes, ironies, and the like, but all of these are traditional elements of films both classical and non-classical.

There are, though, more radical cases. The experimental novelist Michel Butor pointed out that the fact that the book is an object to be manipulated at will harbored the possibilities of innovative storytelling. He pursued those in works like La Modification (1957) and Degrés (1960) and theorized about them in an essay, “The Book as Object.” (3) Along the same lines, once a film becomes a booklike object, it can be composed to encourage multiple replays not merely to appreciate little touches but just to make bare sense of what’s going on in it.

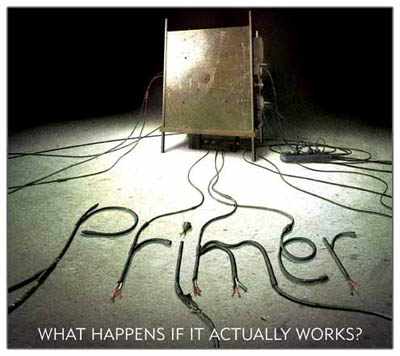

Memento and Primer would seem to be instances. Their makers seem to have designed the films to encourage admirers’ extensive, not to say obsessive, re-viewings. (For analyses of Primer, go here and here.) Again, however, the DVD serves not as a unique format for the film but as a tool that makes analyzing the plots a lot easier than would several visits to the theatre. (4)

There are other possibilities tied to the format itself. The DVD of Max Allan Collins’ Real Time: Siege at Lucas Street Market was designed to permit the viewer some choice of camera angle in certain scenes. At a few points we’re permitted to enlarge the monitors of different surveillance cameras in order to follow one or another strand of action. (Actually, I couldn’t get this feature to work on my players.) Still, in Real Time, the plot action is clear and redundant in the classical manner, so even if you don’t enlarge the screens, maybe you won’t miss much.

Butor suggested that since a book is an object, all in hand at once, a plot could be composed to permit many, equally valid points of entry and exit. Such seems to have been achieved by the DVD version of Greg Marcks’ 11:14. The film is a network narrative, following five characters in a small town as their lives intertwine. The plot is broken into five segments, each one following a character up to the critical moment given in the title. It’s a clever and enjoyable piece of work. In carrying it to DVD, Marcks chaptered it so that you could skip among storylines at will. He explains in an email to me:

It’s a feature on the DVD that I called “character jump,” which allows you to jump to what another character is doing at that same moment in time. Theoretically you could watch the film in an endless circuitous loop because the end is simultaneous with the beginning.

During some scenes of 11:14, a JUMP icon appears and if you press Enter, the scene switches to another character’s storyline—either earlier or later in the theatrical version’s running time. Once in that story, the icon stays on for a bit so that you can return to your point of departure if you want. (4) Presumably for reasons of engineering and disc space, the number of JUMP options remains fairly limited. Still, it’s a fascinating prospect, and it does seem to offer the possibility of your restructuring the plot in fresh ways.

Even in 11:14, however, the story possibilities are closed. As in a Choose Your Own Adventure book, you’re hopping among trajectories that are already designed. The opening remains the opening for every option; no Butor-style starting in the middle. Furthermore, the trajectories themselves are linear, running along a cause-effect pattern very familiar to us from classically constructed stories. (5) We find this often in branching or multiple-draft narratives. I argue in The Way that even the reverse-order disjunctions of Memento sort out along lines to be found in film noir.

Let’s also recall a simple point. Even though the book format offers the sort of mind-bending manipulations Butor celebrates, most literary fiction remains traditionally plotted and narrated. Likewise, we should expect that the arrival of the DVD permits filmmakers who want to tell orthodox stories in orthodox ways keep on doing so. The line of least resistance is straightforward linear presentation.

Speculation 3: The ease of DVD replay can encourage filmmakers to pack their films with more details that repay rewatching. The result might be films that are more “hyperclassical,” to use a term I suggest in The Way Hollywood Tells It –films that are even more tightly woven than we tend to find in the studio years.

Speculation 4: Some filmmakers have made their storylines harder to follow on a single viewing, encouraging DVD replays so we can figure out what’s going on. This strategy makes the films less classical in construction, to a greater or lesser extent.

Speculation 5: A few filmmakers have utilized DVD features to allow greater interactivity than a theatrical screening would grant. In most cases, however, this interactivity rests upon classical guidelines—protagonists with goals, confronting obstacles, conflicting with others, and arriving at a definite conclusion along a linear path.

A stubborn structure

Once upon a time, roughly between the 1920s and the 1960s, movie theatres had a policy of continuous admissions. Metropolitan theatres were sometimes very crowded and patrons had to wait in line outside for seats to be freed up. (Hence the need for ushers to find vacant seats during the screening.) As a result, you might enter in the middle of the movie and watch the film through to the end, sit through shorts and perhaps another feature, and then stay for the opening of the initial film. Hence the expression “This is where we came in.” Doubtless many people planned to see films from beginning to end, but a lot also arrived in medias res.

Someone might speculate that this manner of viewing would encourage filmmakers to indulge in slack plotting. After all, if viewers can come in at any point, a vaudeville-like cascade of acts and incidents—what people are now calling a “cinema of attractions”—would be best. In fact, however, Hollywood feature filmmakers told complex, linear stories of the sort I’ve already mentioned. They didn’t seem to care if viewers were entering midway.

But they really had no choice. If the filmmakers wanted to tell a fairly coherent story, how could they cater to a viewer who might enter at any moment? The only feasible plan, then and now, is just to go ahead and present a story in the linear way, but make sure that it’s presented so clearly that even a viewer entering in the middle can pick up what’s happening. That was, and still is, the default practice. The redundancy of Hollywood storytelling, bent on clear and cogent presentation of the action, is the most effective response to fragmentary viewing.

Hollywood films have been shown in picture palaces, rural playhouses, college classrooms, churches, military bases, and submarines. They’ve appeared on TV, in drive-in theatres, on airline screens, on computer monitors, and now on iPods. In design and execution, the films have stayed remarkably stable. They have relied on our understanding of general principles of storytelling and more specific ones typical of Hollywood. In most cases, this default will stay in place. It works very well, and there’s no alternative that can anticipate all the different ways in which viewers can consume the movie.

Speculation 6: Odd as it sounds, fragmented viewing conditions can encourage coherent storytelling.

Speculation 7: We can’t easily draw conclusions about how films are constructed on the basis of how they’re presented and consumed. Changes in viewing practices don’t automatically entail changes in storytelling.

I’d just add that even in the age of digital media, spectators enjoy greatest freedom not in the way that they manipulate films but in the ways they can interpret them. But even an epic blog has to stop somewhere, so I’ll leave that matter for another time. (6)

(1) You can find the details of our case in Film Art, in Narration in the Fiction Film, in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, in Storytelling in Film and Television, in The Way Hollywood Tells It, and in my forthcoming Poetics of Cinema. Also, see Kristin’s “contrarian” blog entry here.

(2) In high school I loaned Candy to a friend and it made its way among my peers with remarkable speed. When I got it back, the pages were falling out. Somehow, our principal Mr. Brown learned that I was the culprit. He gave me a starchy lecture and announced over the homeroom PA system that I was being reprimanded for “bringing a certain book” to school. Mr. Brown was unmoved by my defense that Candy had gotten fairly good reviews.

(3) Translated in his English-language collection Inventory (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968), pp 39-56. The essay doesn’t seem to be available on the Net. So off to the library with you!

(4) Thanks to Colin Burnett, who tested the 11:14 DVD for me while I’ve been away.

(5) Marcks’ DVD version has allowed us to create a Griffith-style crosscutting of plot strands. Interestingly, network narratives are constructed in two main ways: crosscutting the storylines (as in SHORT CUTS) or presenting them in blocks that we must synchronize in our heads (as in PULP FICTION and GO). Marks’ theatrical version gives us the block version of 11:14, while the DVD reveals one possibility of an intercut one.

(6) I’ve discussed film interpretation in a book (Making Meaning) and in chunks of a forthcoming collection (Poetics of Cinema),

PS, 16 May (New Zealand time): Jason Mittell has a fascinating commentary on this topic at his site, Just TV (which isn’t actually just about TV). Jason argues that television narrative has become more complex in recent years and that videotape and DVD technologies have affected that in some unexpected ways. A must-read!

The Celestial Multiplex

Kristin here—

The Internet is mind-bogglingly huge, and a lot of people seem to think that most of the texts and images and sound-recordings ever created are now available on it—or will be soon. In relation to music downloading, the idea got termed “The Celestial Jukebox,” and a lot of people believe in it. University libraries are noticeably emptier than they were in my graduate-school days, since students assume they can find all the research materials they need by Googling comfortably in their own rooms.

A lot depends what you’re working on. For The Frodo Franchise, studying the ongoing Lord of the Rings phenomenon would have been impossible without the Internet. A big portion of its endnotes are citations to URLs. On the other hand, my previous book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, a monograph on the stylistic and technical aspects of Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, has not a single Internet reference. Lubitsch can only be investigated in archives and libraries, where one finds the films and the old books and periodicals vital to such a project.

Vast though it is, the Internet is tiny in comparison with the real world. Only a minuscule fraction of all the books, paintings, music, photographs, etc. is online. Belief in a Celestial Jukebox usually works only because people tend to think about the types of texts and images and sounds that they know about and want access to. Yes, more is being put into digital form at a great rate, but more new stuff is being made and old stuff being discovered. There will never come a time when everything is available.

Even so, every now and then someone proclaims that in the not too distant future all the movies ever made will be downloadable for a small fee, a sort of Celestial Multiplex. A. O. Scott declared this in “The Shape of Cinema, Transformed at the Click of a Mouse” (New York Times, March 18): “It is now possible to imagine—to expect—that before too long the entire surviving history of movies will be open for browsing and sampling at the click of a mouse for a few PayPal dollars.”

Not only that, but Scott goes on, “This aspect of the online viewing experience is not, in itself, especially revolutionary.” He’s more interested in the idea that online distribution will allow filmmakers to sell their creations directly to viewers. That would be significant, no doubt, but as a film historian, I’m still gaping at that line about “the entire surviving history of movies.” Such availability would not only be “revolutionary,” it would be downright miraculous. It’s impossible. It just isn’t going to happen.

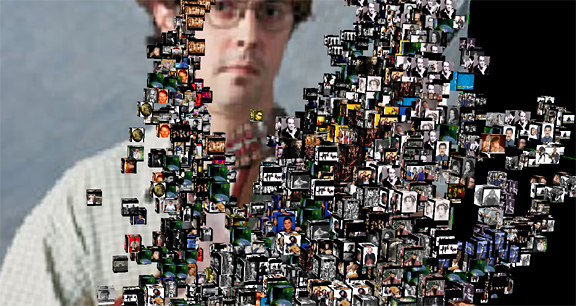

(The image above was generated to publicize the “Search inside the Music” program that is an important part of the Celestial Jukebox. Imagine movie screens with actors’ faces in those little boxes, and you’ve got the Celestial Multiplex.)

I will give Scott credit for specifying “surviving” films. Other pundits tend to say “all films,” ignoring the sad fact that great swathes of our cinematic heritage, especially in hot, humid climates like that of India, have deteriorated and are irretrievably lost.

Dave Kehr has already briefly pointed out some of the problems with Scott’s claims, mainly the overwhelming financial support that would be needed: “Tony Scott’s optimism struck me as, well, a little optimistic.” On the line about “the entire surviving history of movies,” Kehr suggests, “That’s reckoning without the cost of preparing a film for digital distribution — the same mistake made by the author of the recent vogue book ‘The Long Tail’ — which, depending on how much restoration is necessary, can run up to $50,000 a title. None of the studios is likely to pay that much money to put anything other than the most popular titles in their libraries on line.” As Kehr says, the numbers of films awaiting restoration and scanning isn’t in the hundreds, as Scott casually says. No, it’s in the tens of thousands even if we just count features. It’s more like hundreds of thousands or more likely millions if we count all the surviving shorts, instructional films, ads, porn, everything made in every country of the world. To see how elaborate the preservation of even one short medical teaching film can be, go here.

Putting aside the need for restoration, newer films present a daunting prospect. To help put the situation in perspective, let’s glance over the total number of feature films produced worldwide during some representative years from recent decades (culled from Screen Digest‘s “World Film Production/Distribution” reports, which it publishes each June): 1970, 3,512; 1980, 3710; 1990, 4,645; 2000, 3,782; and 2005, 4,603. For me the numbers conjure up the last shot of Raiders of the Lost Ark, only with just stack upon stack, row upon row of film cans.

Scott isn’t the first commentator to prophesy that all films will eventually be on the Internet. It’s an idea that crops up now and then, and it would be useful to look more closely at why it’s a wild exaggeration. It’s not just the money or the huge volume of film involved, though either of those factors would be prohibitive in itself. There are all sorts of other reasons why the advent of practical digital downloading of films will never come close to providing us with the entire history of cinema.

Coincidentally, two experts on this subject, Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Film Archive of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Schawn Belston, Vice President, Film Preservation and Asset Management for Twentieth Century Fox, visited Madison this past week. Mike got his MA here in the Dept. of Communication Arts and now returns about once a year to show off the latest restored print that he has worked on. Schawn isn’t an alum, but he has also visited often enough that most students probably think he is. The two brought us the superb new print of Leave Her to Heaven that Fox and the Academy have recently collaborated on.

I figured it would be very enlightening to sit down with these two and talk about why the Internet is never going to allow us to watch just anything our hearts desire. They kindly agreed, and with my trusty recorder in tow we went for burgers—and fried cheese curds, a commodity not available in Los Angeles—at the Plaza Tavern. I’m grateful for the fascinating insights they provided into some of the less obvious obstacles to putting films on the Internet en masse.

No Coordinating Body

Before we launch in, though, one point needs to be made: there is no single leader or group or entity out there organizing some giant program to systematically put all surviving movies on the Internet. There isn’t a set of guidelines or principles. There’s no list of all surviving films. How would we even know if the goal of putting them all up had been achieved? When the last archivist to leave turned out the light, locked the door, and went looking for a new line of work?

Most of the physical prints that would be the basis for such transfers are sitting in the libraries of the studios that own them or in the collections of public and private archives (including many individuals). The studios would make films available online for profit. The archives might be non-profit organizations, but they still would need to fund their online projects in some fashion, either by government support, from private grants, or by charging a fee for downloads. Most archives are more concerned about getting the money to conserve or restore aging, unique prints than about making them widely available. Preservation is an urgent matter, and making the resulting copies universally available for public entertainment or education is decidedly a secondary consideration.

Mike works for a non-profit archive, Schawn for a studio, so together they provide a good overview of some key problems facing the creation of an ideal, comprehensive collection of movies for download.

Money

People who claim that all surviving films could simply be put on the Internet don’t go into the technology and expenses of how that could be done.

Of course, Schawn says, studios want to “digitize the library.” That phrase is highly imprecise, however. He specifies, “For the purposes of this idea of media being online, available, downloadable, streamable, whatever, that’s something that we’re dealing with now using existing video masters. So there isn’t an extra cost to quote, unquote digitize. But there is a cost to make the compression master, what we’re calling at Fox a ‘mezzanine file,’ which is basically a 50 megabit file. That’s the highest-quality ‘low’ quality version of the content from which you can derive all of the different flavors of compression for the various websites that have downloadable media.

“There’s a huge problem with this, in that Amazon, iTunes, and Google all have a slightly different technical specification of how they need the files delivered to them. If you don’t have this kind of mezzanine file, you have to make a different compressed version for each one of these, which costs something, certainly. It’s not incredibly expensive, but it’s not free.

“So why? What’s the motivation to us to compress at Fox the entire library? I don’t know. Are we going to sell enough copies of Lucky Nick Cain [a 1951 George Raft film] compressed on iTunes to cover the costs of making the compression? I don’t think so.”

Compatibility and the Onrush of Technology

Schawn’s mention of the variety of files needed by the big download services raises the problem of compatibility. It’s not just a matter of supplying the files and then forgetting about the whole thing, assuming that the film is available to anybody forever. What about new standards and formats?

Shawn: “Just as with consumer video, the standard changes, so what used to be acceptable yesterday isn’t acceptable now in terms of technical quality.” As time passes, plug-ins make access faster and cheaper, and eventually the original files don’t look good enough. He points out that currently iTunes can’t download HD. If it becomes possible later, “If you want to get 24 in HD, what Fox will have to do is go and re-deliver all the files in HD.” And presumably re-deliver again when the next big format revolution occurs.

Mike explains further, “Using the mezzanine file, you would just have to continue to reformat it to whatever the players demand. The lowest of the low quality will keep going up as people have broadband and can handle larger chunks of data faster.”

What about the film you’ve already downloaded? You acquire films using plug-ins, which change. Think how often you’re told that an update is now available. If you go ahead and keep updating, the changes accumulate. Eventually you may not be able to play the download you paid for. Quicktime will have moved way beyond what the technology was when you made your purchase.

Schawn and Mike both point out that at this stage in the history of downloading, the level of quality is still pretty bad in comparison with prints of films in theaters or on DVDs. It would be nice to think that the virtual film archive could provide sounds and images worthy of the movies themselves, but that will take a long, long time–not the “before too long” that Scott envisions.

Copyright

I raised another matter: “But what about copyright? Every time I hear something about restoration or bringing something out on DVD, it’s, ‘Well, there are rights problems.’ And some of those rights problems don’t get resolved. I assume that quite a few films that they blithely believe can be slapped up for downloading can’t be slapped up.”

Schawn: “Sure, and there are often not any kinds of provisions in the contract about Internet distribution—obviously! So you’re right, how do you deal with that?”

He pointed to Viva Zapata as a film that Fox has restored but can’t make available due to rights issues. The potential sales are not thought to warrant paying to resolve those issues. “I’m sure there are lots of titles in everybody’s libraries that you can’t just pop up on the Internet and start selling.”

The copyright barrier is worse for archives, which seldom own the exhibition or distribution rights to the films they protect. Usually—though not invariably–the studios do not object to archives owning and preserving prints. Making money through showing them or selling copies would be quite another matter.

Mike described the online presence of archival prints. “On a much smaller scale, this is being attempted in the archive world already, like on Rick Prelinger’s site [Prelinger Archives] or on the Library of Congress’s site, where they’ve put up dozens of moving-image files. True, it’s not independent cinema and it’s mostly commercials and the paper prints that have recently been restored. On Prelinger’s site it’s all the industrial films that he’s collected over the years. That has seen a good amount of traffic, but it hasn’t created new audiences for these films, I would argue. At least, not on a huge scale.”

Prelinger’s site contains only public-domain items, including the ever-popular Duck and Cover, allowing him to avoid the problem of copyright. Similarly, the Library of Congress gives access primarily to films in the pre-1915 era.

Suppose an archive and a film studio both have good-quality prints of a minor American film made in the 1940s. The archive does not have the legal right to put it online, and if the studio decides that it does not have the financial incentive to do so, that film will not be made available for downloading. A private collector might possibly create a file and make it available, but he or she would risk being threatened by the copyright-holder.

Piracy

We briefly discussed the methods used to prevent pirated copies being made from downloaded films. Like DVDs, downloads can be pirated, with people sending copies to their friends or even offering downloads for a fee in competition with the copyright holder. Copy-protection codes might make it necessary for a purchaser to keep a downloaded copy only on a hard-drive without being able to burn it onto a DVD. Another type of code could erase the file once the film had been viewed once or twice. That’s not exactly conducive to the ideal archive of world cinema, where we would hope to be able to study a film in detail if we so choose.

One might think that piracy protection mainly applies to studios, with their need to make money. Mike points out, though, that the need for such protection “even applies to the archival model, too. For films that you mention that have gone out of copyright, there’s still the same costs associated with putting a silent film that no one owns–digitizing it, creating the compressed master that goes on the Web—and they aren’t the kinds of subjects that people are going to get rich on at all, so there isn’t a lot of piracy. You don’t hear many archivists complaining, ‘Hey, you took my 1911 Lubin film, damn you! You can’t put that on your Website. That belongs on the archive’s Website.’ But that scenario becomes more of a likelihood for more popular titles. The obscure 1911 Lubin film is on one extreme, but Birth of a Nation, a well-known silent film a lot more people would like to see, is on the other. Let’s say the highest-quality copy is on the Museum of Modern Art’s Website and can be easily lifted and posted on your own site. And even if you just say, ‘Oh, I’ll charge 99 cents or I’ll charge 50 cents to stream it,’ it’s still going to be someone taking over something that the archive put all of the high-end effort and money into doing. Frankly, I think unless it’s an archive with a national mandate and a little bit higher budget to digitize and to put the contents of their archives online, there’s not going to be any motivation to make that high-end investment up front.”

Thus an archive may simply not bother to put a film on the internet because it can’t guarantee recouping the costs that would be generated.

Language and Cultural Barriers

Scott’s notion of easy access to all of surviving world cinema implicitly depends on an idea that all these films are either English-language or already subtitled or dubbed for English-speaking users.

That’s not true for a start, so there would remain a great deal of work to translate films that have never been released in English-language markets. That’s another huge, expensive task.

Then there’s the opposite side of that coin. For truly complete access, everyone in the world, whatever language they speak, would be able to download and appreciate every film. Of course, there are billions of people without computers or Internet access, and it looks unlikely that being able to go online will become universal anytime soon. (For figures on numbers of people with internet access, check here; percentages can be calculated by clicking on each country and finding the total population. In Tajikistan, for example, .07% of the population was online in 2005. One has to assume that a lot of connections in some of those countries are dial-up, so downloading films would be virtually impossible. [June 21, 2010: In 2008, Tajikistan’s online population has grown to .08%.])

So let’s just say that for the foreseeable future downloadable films would “only” need to be subtitled in the languages of countries or regions where significant numbers of people subscribe to PayPal.

In our conversation, Schawn pointed out that digital compression files mean that there can be huge numbers of versions, with different soundtracks dubbed in or different subtitles added. Technically it’s possible to do all that translation. Still, “it’s very complicated. So for worldwide distribution of anything, like you’re talking about your silent film. If you’re in Pakistan, do you get the American version of the movie or do you get the version of the movie with the intertitles appropriate to wherever it is that you’re showing it? If so, that quickly compounds the amount of stuff that’s digitized.”

I responded, “Yeah, or a 1930s Japanese film put on the Internet for downloading, subtitled in every language where there are people that can pay for it. The more you think about it, the more absurd it becomes.”

Scott must be implying as well that there is some single “original” version of a film and that that version would be the one available in this ideal collection in cyberspace. Yet any archivist or film historian knows that multiple versions of a given film are typically made, depending partly on the censorship laws of the different countries where it is originally shown. In making downloadable files available, does a studio or archive use only the original version of a film made for its country of origin and thus risk having it include material offensive to viewers in some places where it might be downloaded? Or does a whole slew of different versions, one acceptable in, say, Iran, another inoffensive to the Danes, and still another compatible with Senegalese social mores, get put online? How could one even gather all such versions and digitize them? National film archives tend to have government mandates to concentrate primarily on preserving their own countries’ films. Not every version of every film gets saved.

The Bottom Line

For all the reasons noted here and others as well, film availability for download will follow pretty much the same economic principles that have governed film sales in other media. Mike’s opinion is, “Whether they’re from an archive or a studio, I think things’ll start going online in the same pace that they came onto DVD, in an eight to ten-year cycle. And there still will be large gaps.”

Schawn interjects, “Just as there are on DVD.”

Mike concludes, “There’s stuff that will never go online. Yeah, just as on DVD.”

*

A truly celestial screening: a restored 35mm print of Bertolucci’s 1900 projected free, under the stars in the Piazza Maggiore, Bologna, summer of 2006

Movies still matter

Kristin here—

I don’t know whether I should be grateful or not when I read the film trade journals or major newspapers and run across columns bemoaning the decline of the cinema. On the one hand, these give me plenty of fodder for blogging. On the other, they promote a false impression that the movie industry and the art form in general are in far worse shape than they really are.

One recent case in point is Neil Gabler’s “The movie magic is gone,” from February 25, where he says that movies have lost their previous importance in American society and are less and less relevant to our lives.

Gabler makes some sweeping claims. Movie attendance is down because movies have lost the importance they once had in our culture. Our obsession with stars and celebrities has replaced our interest in the movies that create them. Niche marketing has replaced the old “communal appeal” of movies. The internet intensifies that division of audiences into tiny groups and fosters a growing narcissism among consumers of popular culture. Audiences have become less passive, creating their own movies for outlets like YouTube. In videogames, people’s avatars make them stars in their own right, and the narratives of games replace those of movies.

Films will survive, Gabler concludes, but they face “a challenge to the basic psychological satisfactions that the movies have traditionally provided. Where the movies once supplied plots, there are alternative plots everywhere.” This epochal challenge, he says, “may be a matter of metaphysics.”

All this is news to me, and I think I have been paying fairly close attention to what has been going on in the moviemaking sphere over the past ten years—the period over which Gabler claims all this has been happening. Evidence suggests that all of his points are invalid.

1. Gabler states that “the American film industry has been in a slow downward spiral.” Based on figures from Exhibitors Relations, a box-office tracking firm, attendance at theaters fell from 2005 (a particularly down year) to 2006. A Zogby survey found that 45% of Americans had decreased their movie-going over the past five years, especially including the key 18-24-year-old audience. “Foreign receipts have been down, too, and even DVD sales are plateauing.” Such a broad decline “suggests that something has fundamentally changed in our relationship to the movies.”

Turning to a March 6 Variety article by Ian Mohr, “Box office, admissions rise in 2006,” we read a very different account of recent trends. According to the Motion Picture Association of America, admissions rose, “with 1.45 billion tickets sold in 2006—ending a three-year downward trend.” Foreign markets improved as well, “where international box office set a record of $16.33 billion as it jumped 14% from the 2005 total.” Within the U.S., grosses rose 5.5% over 2005.

We should keep in mind that part of the perception of a recent decline comes from the fact that 2002 was a huge year for box-office totals, mainly stemming from the coincidence of releases of entries in what were then the four biggest franchises going: Spider-man, The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Star Wars. There was almost bound to be a decline after that. Such films make so much money that the fluctuations in annual box-office receipts in part reflect the number of mega-blockbusters that appear in a given year.

Looking at the longer terms, though, the biggest decline in U.S. movie-going was in the 1950s, as television and other competing leisure activities chipped away at audiences. Even so, the movies survived and from 1960 onward annual attendance hovered at just under a billion people. From 1992 on, a slow rise occurred, until by 1998 it reached roughly 1.5 billion and has hovered around that figure ever since, with a peak in 2002 at 1.63 billion. Variety’s figure of 1.45 billion for 2006 fits the pattern perfectly. In short, there has been no significant fall-off since the 1950s. (See the appendix in David’s The Way Hollywood Tells It for a year-by-year breakdown.) The article also states that industry observers expect 2007 to be especially high, given the Harry Potter, Spider-man, and Pirates of the Caribbean entries due out this year. About a year from now, expect pundits to be seeking reasons within the culture why movie-going is up. I suspect they will find that we are looking for escapism. Safe enough. When aren’t we?

Apart from theatrical attendance figures, let’s not forget that more people are watching the same movies on DVDs and on bootleg copies that don’t get into the official statistics.

2. Gabler claims that movies are no longer “the democratic art” that they were in the 20th Century. During that century, even faced with the introduction of TV, “the movies still managed to occupy the center of American life….A Pauline Kael review in the New Yorker could once ignite an intellectual firestorm … People don’t talk about movies the way they once did.”

Maybe the occasional Kael review created debate, as when she claimed that Last Tango in Paris was the “Rite of Spring” of the cinema. I think we all know by now that she was wrong. A lot of us even knew it at the time, and it’s no wonder that people argued with her. I doubt that attempts to refute her claims there or in other reviews reflected much about the health of the general population’s enthusiasm for movies.

More crucially, however, people do still talk about the movies, and lively debates go on. It’s just that now much of the discussion happens on the internet, on blogs and specialized movie sites, and in Yahoo! groups. (Who would have thought that David’s entry on Sátántango would be popular, and yet there turn out to be quite a few people out there passionately interested in Tarr’s film.)

Some would see the health of movie fandom on the internet as a sign that the cinema has become more democratic than ever. Now it’s not just casual water-cooler talk or a group of critics arguing among themselves. Anyone can get involved. The results range from vapid to insightful, but there’s an immense amount of discussion going on.

3. Interest in movies has eroded in part due to what Gabler has termed “knowingness.” By this he means the delight people take in knowing the latest gossip about celebrities. Movies have declined in importance because they exist now in part to feed tabloids and entertainment magazines.

“Knowingness” is basically a taste for infotainment. Infotainment had been around in a small way since before World War I in the form of fan magazines and gossip columns. It really took off beginning in the 1970s, with the rise of cable and the growth of big media companies that could promote their products—like movies—across multiple platforms. (I trace the rise of infotainment in Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise.) It’s not clear why one should assume that a greater consumption of infotainment leads to less interest in going to movies.

People in the film industry seem to assume the opposite. Studio publicity departments and stars’ personal publicity managers feed the gossip outlets, in part to control what sorts of information get out but mainly because those outlets provide great swathes of free publicity. With the rise of new media, there are more infotainment outlets appearing all the time. Naturally this trend is obvious even to those of us who don’t care about Britney’s latest escapade. But I doubt that watching Britney coverage actually makes people less inclined to go to, say, The Devil Wears Prada, one of the mid-range surprise successes that helped boost 2006’s box-office figures.

4. Movies have lost their “communal appeal” in part because the public has splintered into smaller groups, and the industry targets more specialized niche markets. According to Gabler, “the conservative impulse of our politics that has promoted the individual rather than the community has helped undermine movies’ communitarian appeal.”

Let’s put aside the idea that conservative politics erode the desire for community. The extreme right wing has certainly put enough stress on community and has banded together all too effectively to promote their own mutual interests lately. But is the industry truly marketing primarily to niche audiences?

Of course there are genre films. There always have been. Some appeal to limited audiences, as with the teen-oriented slasher movie. Yet despite the continued production of low-budget horror films, comedies, romances, and so on, Hollywood makes movies aimed at the “family” market because so many moviegoers fit into that category. Most of the successful blockbusters of recent years have consistently been rated PG or PG-13. According to Variety, 85% of the top 20 films of 2006 carried these ratings. Pirates of the Caribbean, Spider-man, Harry Potter—these are not niche pictures, though distributors typically devise a series of marketing strategies for each film, with some appealing to teen-age girls, others to older couples, and so on.

(An important essay by Peter Krämer discusses blockbusters with broad appeal: “Would you take your child to see this film? The cultural and social work of the family-adventure movie,” in Steve Neale and Murray Smith’s anthology, Contemporary Hollywood Cinema, published by Routledge in 1998.)

The result is that, despite the fact that niche-oriented films appear and draw in a limited demographic, there are certain “event” pictures every year that nearly everyone who goes to movies at all will see—more so than was probably the case in the classic studio era. Those films saturate our culture, however briefly, and surely they “enter the nation’s conversation,” as Gabler claims “older” films like The Godfather, Titanic, and The Lord of the Rings did. By the way, the last installment of The Lord of the Rings came out only a little over three years ago. Surely the vast cultural upheaval that the author posits can’t have happened that quickly.

5. The internet exacerbates this niche effect by dividing users into tiny groups and creates a “narcissism” that “undermines the movies.”

See number 2 above. I don’t know why participating in small group discussions on the internet should breed narcissism any more than would a bunch of people standing around an office talking about the same thing. In fact, there are thousands of people on the internet spending a lot of their own time and effort, many of them not getting paid for it, providing information and striving to interest others in the movies they admire.

The internet allows likeminded people to find each other with blinding speed. Often fans will stress the fact that what they form are communities. They delight in knowing that many share their taste and want to interact with them. Some of these people no doubt have big egos and are showing off to whomever will pay attention. Narcissism, however, implies a solitary self-absorption that seems rare in online communities.

A great many of these communities form around interest in movies. In this way, the internet has made movies more important in these people’s lives, not less.

6. Audiences have become active, creating their own entertainment for outlets like YouTube, and are hence less interested in passive movie viewing. These are situations “in which the user is effectively made into a star and in which content is democratized.”

No doubt more people are writing, composing, filming, and otherwise being creative because of the internet. Some of this creativity and the consumption of it by internet users takes up time they could be using watching movies.

Yet anyone who visits YouTube knows that a huge number of the clips and shorts posted there are movie scenes, trailers, music videos based on movie scenes, little films re-edited out of shots taken from existing movies, and so on. In some cases the makers of these films have pored over the original and lovingly re-crafted it in very clever ways. A lot of the creativity Gabler notes actually is inspired by movies. Some people post their films on YouTube because they are aspiring movie-makers hoping to get noticed. The movie industry as a whole is not at odds with YouTube and other sites of fan activity, despite the occasional removal of items deemed to constitute piracy.

7. New media allow these active, narcissistic spectators to star in their own “alternative lives.” “Who needs Brad Pitt if you can be your own hero on a video game, make your own video on YouTube or feature yourself on Facebook?”

In discussing videogames, Gabler perpetuates the myth that “video games generate more income than movies.” This is far from being true, and hence his claim that videogames are superseding movies is shaky. (I debunk this myth in Chapter 8 of The Frodo Franchise.)

Even the spread of videogames does not necessarily mean that fans are deserting movies. On the contrary, there is evidence that people who consume new media also consume the old medium of cinema. Mohr’s Variety article reports on a recent study by Nielsen Entertainment/NRG: “Somewhat surprisingly, the same study revealed that the more home entertainment technology an American owns, the higher his rate of theater attendance outside the home. People with households containing four or more high-tech components or entertainment delivery systems—from DVD players to Netflix subscriptions, digital cable, videogame systems or high-def TV—see an average of three more films per year in theaters than people with less technology available in their homes.”

Apart from the shaky factual basis of the column, what does the end-of-cinema genre tell us about how trends get interpreted by commentators?

As I pointed out in my March 9 entry, some commentators explain perceived trends in film by generalizing about the content of the movies themselves. “As soon as some trend or apparent trend is spotted, the commentator turns to the content of the films to explain the change. If foreign or indie films dominate the awards season, it must be because blockbusters have finally outworn their welcome. If foreign or indie films decline, it must be because audiences want to retreat from reality into fantasy. It’s an easy way to generate copy that sounds like it’s saying something and will be easily comprehensible to the general reader.”

Gabler is arguing for something different—something that, if it were true would be more depressing for those who love movies. He’s not positing that movies have failed to cater to the national psyche. He’s claiming that other forces, largely involving new media, have changed that national psyche in a way which moviemakers could never really cope with. Cinema as an art form cannot provide what these other media can, and spectators caught up in the options those media offer will never go back to loving movies, no matter what stories or stars Hollywood comes up with. By his lights, the movies are apparently doomed to a long, irreversible decline.

Hollywood has what I think is a more sensible view of new media. Games, cell phones, websites, and all the platforms to come are ways of selling variants of the same material. Film plots are valuable not just as the basis for movies but because they are intellectual property that can be sold on DVD, pay-per-view, and soon, over the internet. They can be adapted into video games, music videos, and even old media products like graphic novels and board games.

Not only Hollywood but the new media industries have already analyzed the changing situation and come up with new approaches to dealing it. Check out IBM’s new Navigating the media divide: Innovating and enabling new business models. Those models include “Walled communities,” “Traditional media,” “New platform aggregation,” and “Content hyper-syndication,” which, the authors predict, “will likely coexist for the mid term.”

In other words, traditional media like the cinema aren’t dying out. No art form that has been devised across the history of humanity has disappeared. Movies didn’t kill theater, and TV didn’t kill movies. It’s highly significant that the main components of new media—computers, gaming consoles, and the internet—have all added features that allow us to watch movies on them.

The big movies still get more press coverage than the big videogames partly because they usually are the source of the whole string of products. If a movie doesn’t sell well, it’s likely that its videogame and its DVD and all its other ancillaries won’t either. That is a key word, for many of the new media that Gabler mentions produce the ancillaries revolving around a movie. So far, very few movies are themselves ancillary to anything generated with new media. If you doubt that, check out Box Office Mojo’s chart of films based on videogames, which contains all of 22 entries made since 1989.

One final point. Film festivals are springing up like weeds around the world. Enthusiasts travel long distances to attend them. That’s devotion to movies. From last year’s Wisconsin Film Festival, add 26,000 tickets sold to that 1.5 billion attendance figure.

Movies still matter enormously to many people. New media have given them new ways to reach us, and us new ways to explore why they matter.

World rejects Hollywood blockbusters!?

(T)Raumschiff Surprise–Period 1

Kristin here—

I’ve just returned from two weeks in Egypt, and on the ten-hour flight from Cairo to New York, I had plenty of time to absorb the contents of the February 24-25 edition of the International Herald Tribune. One of its articles, “Hollywood rides off into the setting sun,” proclaimed the imminent decline of Hollywood.

The co-authors of this article are Nathan Gardels, editor of NPQ and Global Viewpoint, and Michael Medavoy, CEO of Phoenix Pictures and producer of, among many others, Miss Potter. These two are, according to the biographical blurb accompanying the article, writing “a book about the role of Hollywood in the rise and fall of America’s image in the world.”

The Tribune piece is a slightly abridged version of an essay that appeared on The Huffington Post on February 21, 2007 under the title “Hearts and Minds vs. Shock and Awe at the Oscars.” The subject is not really the Oscars, though, but the supposed decline in interest in American blockbusters, both in the USA and abroad. The authors make a series of claims to suggest that Hollywood is about to lose its “century-long” status as the center of world filmmaking. (Actually American films didn’t gain dominance on world markets until early 1915, but that’s a quibble in the face of the other shaky claims made here.)

1. Foreign films are getting all the awards and prestige this year. “Films by foreigners such as ‘Babel,’ ‘The Queen’ and ‘Volver’ that make little at the box office are winning the top awards while the big Hollywood blockbusters, which make all the money, much of it abroad, are being virtually ignored.” Gardels and Medavoy point out that even veteran director Clint Eastwood figured prominently in the nominations by making a Japanese-language film.

Several objections can be made to this. Technically The Queen is foreign, but it’s not foreign-language. Besides, British films have figured in the Oscars since Charles Laughton won as Best Actor by playing a king in The Private Life of Henry VIII back in 1933. Let’s factor out British films, shall we?

Of course Gardels and Medavoy couldn’t know this when they wrote the piece, but none of those “foreign” films won. An American genre film did. A much-respected Hollywood director finally got an Oscar as best director. He remade a Hong Kong film, secure in the knowledge that most Americans won’t watch a foreign-language import like Infernal Affairs.

Plenty of non-foreign films get awards and prestige. There have been years—like 2005—when most of the best-picture nominees were English-language art-house films like Crash and Brokeback Mountain. If The Departed hadn’t been crowned Best Picture this year, one other good contender would have been Little Miss Sunshine. Think back over how many indies have won Best Picture in the last decade or so. The English Patient and Chicago (both Miramax) come to mind. (Gardels and Medavoy never make mention of independent American films, since their argument presumes that non-formulaic films come only from abroad.)

2. Foreign films show “the world in transition as we are living it.” That is, they reflect the real world and hence are more admired and more admirable. In contrast most “American filmmakers too often grind out formulaic, shock and awe blockbusters.”

Again, there are plenty of American films that don’t fall into the “blockbuster” category. Directors like Quentin Tarantino, David Lynch, Tim Burton, the Coen Brothers, and Christopher Nolan are admired internationally for their unconventional films. Conversely, most films made in foreign countries are no less formulaic than ours. Other countries’ popular comedies, crime films, and horror pics are almost never imported into the USA.

3. Hollywood’s blockbusters “may be winning the battle of Monday morning grosses, but are losing the war for hearts and minds.”

Whose hearts and minds are the authors talking about? Doesn’t a film win hearts and minds by drawing people into theaters? So if blockbusters are popular, aren’t they, at least in some sense, winning hearts and minds? Obtaining Oscar nominations means these films have won the Academy members’ hearts and minds, or in the case of the many critics’ awards, the hearts and minds of journalists.

4. “Audience trends for American blockbusters are beginning to show a decline as well, both at home and abroad.” According to Gardels and Medavoy, the fact that films now gross more abroad than at home suggests that the American public is tired of these big pictures.

This claim is self-contradictory. If blockbusters make more in foreign countries than in the USA, then there would not appear to be evidence for a decline of audiences for such film abroad—unless, of course, there has been an overall decline in box-office income worldwide. That’s not true. In the past four years, two films, The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King and Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest, have made over a billion dollars each internationally. They now stand at, respectively, second and third on the all-time box-office chart (in unadjusted dollars).

Even if we assume that just Americans are getting tired of their own formulaic films, the authors’ argument doesn’t work. They lump Titanic, Jurassic Park, and Star Wars Episode I—The Phantom Menace together with Mission Impossible III and Poseidon as having earned large percentages of their worldwide box-office income outside the USA. Clearly, though, the cases are not comparable. The first three were enormously successful in the USA as well as abroad. Similarly, The Lord of the Rings and the Harry Potter series have brought in around two-thirds of their income outside the US, but one would hardly claim that Americans didn’t like them. The Da Vinci Code brought in over 71% of its total gross abroad but in 2006 it was also the fifth highest-grossing film in the American market.

The authors have chosen two films, Mission: Impossible III and Poseidon, to support their case. Yet in general big action films that perform poorly or even flop in the American market tend to do better in foreign countries, especially if they have auteur directors and big stars. Other examples of recent years have been Oliver Stone’s Alexander and Ridley Scott’s Kingdom of Heaven. Indeed, the importance of stars in selling Hollywood films can hardly be overemphasized. For instance, Tom Cruise is enormously popular in Japan, where Mission: Impossible III grossed $44 million of its $398 million worldwide income. There are few comparable international stars working in foreign-language films.

The rising proportion of receipts abroad results largely from reasons other than any putative decline in the popularity of American cinema. For one thing, rising prosperity in developing countries has made movie-going more affordable, and hence there are more movie-goers. The fall of Communism and the new profit orientation in China have opened large new markets for American films. Most crucially, a huge boom in the construction of multiplexes in South America, Europe, and much of Asia during the 1990s and early 2000s raised the number and cost of tickets sold outside the US. It isn’t the American market that has shrunk. It’s the foreign market that has expanded.

Moreover, comparisons between the total box-office income of films within the American market and in foreign ones are often misleading due to currency fluctuations. The recent weakness of the American dollar against many other currencies has made it considerably easier for those in other countries to see Hollywood’s products. Theatrical income does not necessarily reflect the number of tickets sold or the price of those tickets in local currencies. Hence raw statistics may not accurately indicate the actual popularity of any given title.

5. Countries increasingly are favoring their domestically produced films. “Even long-time American cultural colonies like Japan and Germany are beginning to turn to the home screen.”

This isn’t a new and consistent trend. Some countries have been doing quite well in their own markets for years, partly due to government subsidies for the film industry. France is one such market. Germany had a good year in 2006, but 2005 was a bad one. Many such successes are cyclical. Recently films made in Denmark and South Korea have gained remarkable portions of their domestic film markets, and if they decline, other countries will take their places for a period of relative prosperity.

We should also keep in mind that some countries have exhibition quotas for domestic films. South Korea, which provides government subsidies for filmmaking, in recent years has also required that 40% of exhibition days be given over to domestic films. That quota was halved to 20% last July 1, with filmmakers fearing a surge in competition from Hollywood. In fact September saw the Korean share of the domestic market rise to 83%, but this was largely due to two big hits: The Host and Tazza: The High Rollers. Such success can be ephemeral, however, and the government has recently imposed a tax on movie tickets designed to generate a fund for supporting local filmmaking. Variety’s Asian branch has recently predicted a slump in South Korea for 2007.

Moreover, German or Danish films doing well in their own markets doesn’t mean that they’re beating Hollywood at its own game. American films are truly international products, and blockbusters play in most foreign markets. A non-English-language market like Denmark may produce films that gain considerable screen time at home, but they do not circulate outside the country on nearly the scale of the American product.

Take, for example, the most successful German filmmaker of recent years, actor-director Michael “Bully” Herbig (on the left in the frame above). Within Germany his wildly popular comedy Der Schuh des Manitu (2001) sold almost as many tickets as Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, and his over-the-top gay Star Trek parody (T)Raumschiff Surprise—Period 1 (2004) grossed more than twice as much as Spider-Man 2. Most people outside of Germany have never heard of him or his films. There are comic stars like him in many countries. In general popular local comedies—many of them as formulaic as any Hollywood product—don’t travel well.

[Added March 9:

More evidence for my claims that successful foreign-language films often don’t circulate widely outside their countries of origin comes in the February 23 issue of Screen International. In an essay entitled “Calling on the Neighbours,” Michael Gubbins discusses new funding that the European Union is putting into film specifically to promote the wider distribution of films. “The performance of European films outside their home markets remains one of the thorniest issues for the EU’s policy-makers,” Gubbins writes. “Last year’s box-office recovery in many European territories was largely built on the success of local films in local markets and a number of Hollywood blockbusters.”

In 1995, production within Europe totaled 600 films, and it rose to 800 films in 2005. Yet “that rise in production has not been matched by admissions, which have fluctuated strongly over the late five years. There has been little to suggest that increased production has helped European films travel beyond their borders.”]

6. The competition from increasingly successful national cinemas “suggests that we may be seeing the beginning of the end of the century-long honeymoon of Hollywood, at least in its American incarnation, with the world.”

I don’t know what the authors mean by “Hollywood, at least in its American incarnation.” Has Hollywood existed elsewhere?

Actually, I think that Hollywood may well be in decline, at least as a center for filmmaking in the sense of planning, shooting, and post-producing a movie. That isn’t happening, however, for the reasons that Gardels and Medavoy offer in their article.

One factor is the globalization of film financing. Many films these days are co-productions between companies in different countries. It’s sometimes hard to determine the nationality of a film, given its several participants. The English language, however, remains central to most internationally successful films, and that is unlikely to change any time soon. The most popular stars still tend to come from English-speaking countries or to be able to speak English well, as actors like Juliette Binoche and Penélope Cruz can.

Another factor in globalization is the increasing tendency to make American-based productions partly or entirely abroad. Off-shore production has actually been fairly common since World War II. In the post-war austerity, many countries restricted how much currency could be taken out, and Hollywood firms spent their income by covering the production costs of films made abroad.

Even with the easing of such restrictions, the trend continued. The most traditional modern reason is simply cost-cutting through inexpensive labor and other expenses—advantages that have long been found in Eastern European countries. More recently countries have seen the economic advantages of an environmentally friendly enterprise like filmmaking. More and more of them have put various tax and other financial benefits into place in an effort to be competitive in the search for off-shore productions. For example, the February 2-8, 2007 issue of Screen International contains an ad placed by the Puerto Rico Film Commission (p. 40) declaring that “Puerto Rico is Ready for Action” and offering a remarkable 40% rebate on local expenditures. It also touts the country’s “experienced bilingual local crews” and its “infrastructure.”

One important cause for the off-shore trend that I deal with in The Frodo Franchise is the fact that technological change now offers the possibility of making films entirely abroad, from planning to post-production. Ten years ago it would have been almost unthinkable to have sophisticated special effects created by anyone other than the big American specialty firms like Rhythm and Hues or Industrial Light & Magic. Now world-class digital effects houses are springing up around the globe, and one of the top firms, Weta Digital, is located in a small suburb of Wellington, New Zealand. When a huge, complex production like The Lord of the Rings can be almost entirely made in a country with a miniscule production history, there is far less reason for American producers to confine any phase of their projects to the traditional capital of filmmaking.

There may indeed be an ongoing decline in Hollywood’s importance in world cinema, but it isn’t happening quickly. For one thing, there is no reason to think that US firms will soon cease to be the main sources of financing and organization of filmmaking. Even if Hollywood stopped making films and just distributed the most popular ones from abroad and from American indies, it would remain the most important locale for the film industry. As anyone who studies or works in that industry knows, distribution is the financial core of the whole process.

Finally, we shouldn’t forget that since early in the history of the cinema the USA has been far and away the largest exhibition market for films. No other single country can match it, and Europe’s attempts to create a united multi-national market to rival it have so far made slow progress. With such a firm basis, the Hollywood industry can simply afford to spend more on its films than can firms in most countries. Expensive production values help create movies that have international appeal, in part precisely because they are blockbusters of a type that are rarely made anywhere else.

In the international cinema, “shock and awe” and “hearts and minds” aren’t always as far apart as we might think.

Gardels and Medavoy’s analysis of Hollywood vs. foreign films falls into a common pattern within journalistic writing on entertainment. As soon as some trend or apparent trend is spotted, the commentator turns to the content of the films to explain the change. If foreign or indie films dominate the awards season, it must be because blockbusters have finally outworn their welcome. If foreign or indie films decline, it must be because audiences want to retreat from reality into fantasy. It’s an easy way to generate copy that sounds like it’s saying something and will be easily comprehensible to the general reader.

Such explanations depend on considerable generalizations that are usually made without taking into account the context of industry circumstances. Fluctuations like currency rates, tax loopholes, genre cycles, quotas, labor-union agreements, and similar factors interact in complex ways. All these are really difficult to keep track of and analyze, and most writers don’t bother, even though that would seem to be part of their job.

Almost inevitably commentators also fail to note that films typically take a very long time to get from conception to screen. Most releases of today actually reflect trends that were happening a few years ago. The world film industry is just too cumbersome to turn on a dime, or even on a few billion dollars.