Archive for the 'PANDORA’S DIGITAL BOX: The Blog Series' Category

Pandora’s digital box: The last 35 picture show

The Goetz and Goetz Junior Theatres, Monroe, Wisconsin, 1936.

DB here:

Eighty years ago the Goetz Theatre of Monroe, Wisconsin opened its doors. Last Sunday it screened the last 35mm prints it will ever show. On Tuesday, it became a digital cinema.

I sometimes find myself wishing I had been alive and sentient when exhibitors migrated from storefronts to dedicated venues in the 1910s, when they wired silent-movie venues for talkies (late 1920s-early 1930s), or when they converted to widescreen in the early 1950s. (For this last change, I was around but not sentient.) Think of all I could have learned about the stuff I study at a long remove now. Today I’m living through another time of technological upheaval, so I’m trying to catch up with it.

There are about 39,000 screens operating in the US, and about half are controlled by five major chains: Regal Entertainment Group, AMC Entertainment, Cinemark, Carmike, and Rave. Most of the screens are in population centers and are housed in multiplexes, which introduced economies of scale to the exhibition sector. Those economies make it relatively easy for the big chains to convert to digital. As a follow-up to my post on digital conversion at a local AMC multiplex (here), I wondered how the process affects a small-town exhibitor. After all, thousands of screens across the country belong to regional circuits or are mom-and-pop operations.

So I went to Monroe.

Local boys make good

Wisconsin is more than cheese and beer, but both have shaped the history of Monroe. The town grew in the 1890s with an influx of German-speaking Swiss immigrants, like those who founded the much smaller New Glarus. In the middle of farming country, Monroe became a center of signature Wisconsin commerce. It had the Joseph Huber Brewing Company, founded as the Bissinger brewery around 1845. It’s the home of the Berghoff line and other tasty beers. In 1926 an enterprising UW graduate modernized the town’s cheese industry by creating the Swiss Colony, a mail-order firm that offered cheese, sausage, and baked goods. The Swiss Colony still employs several thousand Monroe citizens and now holds a considerable portfolio of other brands.

While many small towns are shrinking, Monroe has had a steady population of about 10,000 since 1980. It’s a very pretty place, with a well-preserved town square centering on a towering Romanesque county courthouse. Elsewhere are some well-wrought Victorian homes. The town’s Swiss heritage is preserved in several restaurants, social clubs like Turner Hall, and civic events, notably the Cheese Days celebration.

Monroe had a succession of movie houses. Before 1920 there were the Nickelodeon, the Star, the Crystal, and the Lyric. Several of these were managed or owned by Leon Goetz, an early traveling film entrepreneur. He had run films in tent shows and town halls before settling in Monroe. In 1916 he opened the Monroe, the first movie house he built from scratch.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

Leon Goetz was a risk-loving man. To build a 500-seat film theatre in a town with about 4500 people reflects not only the growing popularity of movies but a conviction that the business had a future. In addition, the many farms and little towns around would supply customers; Monroe is the county seat of Green County, so people came here to transact business as well as to shop. Then as now, the nearest competitors to a Monroe theatre were over twenty miles away.

With his brother Chester as partner, Leon owned or managed other theatres in the area, including ones in Beloit and Janesville. The brothers’ biggest triumph, however, was building the Goetz Theatre. Opening on 2 September 1931, it was of semi-Moorish design, with faux balconies and moody cloud-and-star lighting on the ceiling. Light brown brick and darker brown terracotta inlays finished the outside. The lobby was forty feet high, with a gold finish and many trappings and fixtures.

Some unexpected innovations included seats equipped with earphones for the hard of hearing. The screen was 20 feet wide and fifteen feet tall. Accounts of the size range from 800 to 1000 seats. In all, the Goetz was said to have cost $125,000.

The Monroe had presented sound films using a system of Leon’s devising, but the Goetz was a step up, as the editors of the Monroe Evening Times indicated:

It should raise inestimably the respect with which talkies are looked upon locally and attract many persons who heretofore did not care to see pictures under the conditions in which they were shown.

The Goetz has run ever since. It’s said to be the oldest continuous family-operated movie house in the Midwest.

Leon retired to Florida but Chester stayed in the business, opening the Goetz Junior on Christmas day, 1936. It was “ultra modern,” as it advertised itself, with the Western Electric Mirrophonic sound system and using streamlined design elements, like glass brick. Holding only 275 seats, it sometimes showed films not screened at the Goetz across the street, but other times it would screen the same films–sometimes on the same night, with reels rushed back and forth.

Soon Chester had competition from the Chalet, a 500-seat house around the corner. According to local memory, Chester cut ticket prices and then bought the floundering Chalet as a third Goetz house. Chester’s sons Robert and Nathan joined the business. Under Robert’s leadership, their company built the Sky-Vu Drive-in in 1954, and it too has been running without interruption every summer.

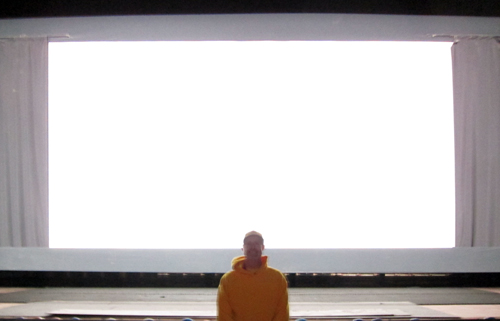

The postwar decline in movie attendance may have hit the family’s circuit. The Chalet and the Goetz Junior closed. In the 1980s and 1990s two screens were added at the Goetz, but unlike most old theatres that went multi-screen, the venue wasn’t split up. The new houses were converted from adjacent retail spaces. Visit the Goetz today and you’ll see the original auditorium. There are fewer seats, but it’s still enormous, as you can see from the front.

The third generation

Robert “Duke” Goetz. Behind him, counterclockwise, pictures of Conrad Goetz, Nathan as a child, Robert as a child, young Chester, and John. In the center, Chester Goetz.

For many years the downtown theatre and the Sky-Vu have been managed by Robert “Duke” Goetz, Robert’s son. He has a masters degree in landscape architecture from Harvard, but he’s been running the family business. He does everything from programming the movies and designing the website to wrench-and-hammer work on the place. He’s worked on heating, carpentry, and acoustic matters. Talk with him and you’ll hear about the tough times small-town exhibitors have faced over the last two decades. I learned as well some pressures on exhibition that I never thought about.

Duke Goetz has a commitment to showmanship and quality of presentation. The Goetz website has old-fashioned razzle-dazzle, including neon colors. (Chester liked bright colors in his houses.) On another page of the site you’ll see this:

Last Friday I saw Duke tell a gaggle of teenagers to shut off their cell phones, and he watched to make sure they did. The same pursuit of a good movie experience shows in Duke’s special attention to sound. Convinced that DTS is the best sound system for his venues, he has outfitted his smaller auditoriums with hard-hitting speaker systems. He installed tip-back seats, stadium seating in one house, and one belt-driven projector for steadier images.

Despite the commitment to quality, and programming that brings in family fare matched to local tastes, business has been rocky. Duke recalls some high points: 1993, when Jurassic Park did spectacularly at both the Goetz and the Sky-Vu; 1998, when Titanic brought in as many as a thousand viewers a night; and 2002, his best year in recent memory. That year was an exceptional spike for the industry as a whole, with estimated admissions of 1.57 billion, so just about anything less looks like a decline. Kristin talks about this effect here.

Duke’s business stayed flat but solid until 2007, when both the drive-in and the downtown screen began to slump. Business flattened out at a lower level through 2011. The only bright spot this year was Twilight: Breaking Dawn; the midnight premiere drew about 150 customers, mostly high-schoolers.

A good night at all three indoor screens is 300-350 tickets, but the Sky-Vu can reliably draw many more. Duke recalls one evening when the drive-in had over 1100 customers and sold 114 handmade pizzas. Today, even with competition from another local drive-in, the Sky-Vu’s summer schedule bolsters the bottom line significantly.

Why the falling off in recent times? I had expected the standard macro-explanations: the internet, video games, etc. But Duke’s main rival, he believes, is sports. In a town like Monroe, high school sports are central to community life, so Friday night football and basketball games draw not only teens but parents. With the rise of women’s athletics, the middle and high schools schedule plenty of games across the weekend. Add in the fact that televised football in the fall breaks up Saturday (the UW Badgers) and Sunday afternoons (the Packers), and you have a client base that isn’t focused so much on movies. Even the Christmas-New Year corridor, normally a brisk business period, is likely not to help much this time. The New Year starts on a weekend, so that the Packers’ final game on Sunday and the Badgers in the Rose Bowl on holiday Monday will compete with Duke’s screenings.

After three tough years, Duke looks at things realistically. He hires part-time staff to project, sell concessions, and keep an eye on the house, so he’s his only full-time employee. He adds: “I have not been paid since August 2010.” Digital, he admits, is chancy in this business climate. “But without digital, I’m gone.”

Duke goes digital

Duke Goetz saw his first digital screening around 2000 at a convention of the National Association of Theatre Owners (NATO). What attracted him was the edge-to-edge screen brightness. Judging by what I saw on Friday (from down front), the 1.85 image in 35mm at the Goetz is quite sharp, but Duke had long been unhappy with the inevitable falling-off of light toward the edges of any film display. The tendency is exaggerated in anamorphic (2.40) films, which have become more common. And the bigger the screen, the greater the tendency toward a hot spot in the center. In addition, Duke liked the punchier color in digital.

So he was intrigued. “I’d have loved to have done it ten years ago.” But then there was still debate about trustworthy delivery systems (the Net? satellite?) and the cost was astronomical, about $125,000 per projector. Last summer, though, it became clear that the digital wave was cresting, and time was running out for 35mm film. Also running out were the plans for the Virtual Print Fee, whereby the studios partially subsidize the cost of a theatre’s changeover.

This fall Duke took the plunge, arranging for three new NEC projectors from companies and installers he’s known for years. His final analog shows were last weekend. On Monday all houses were closed. By Tuesday night, the Goetz was running a digital copy of New Year’s Eve, which it had run in 35mm only a couple days before. By this coming weekend, all the digital screens are expected to be in action. Duke isn’t going with 3D, partly because he can’t justify the upcharge and partly because he’s not convinced it attracts enough extra business.

I was there for the Friday night 35 shows, and I re-visited on Tuesday. The whole changeover was less dramatic than I expected. In two of the houses, the old projectors were simply moved aside and the new ones sat stolidly in their place.

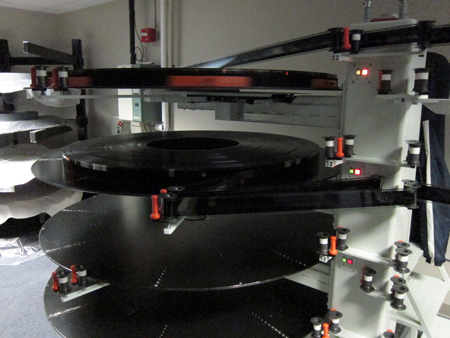

The gigantic platters were stacked in the hallway.

Reels, rewinds, and splicers sat in corners. All of the 35mm projectors were relatively new, but now one is now in the lobby as a historical artifact.

Duke thinks that digital will be even better for the Sky-Vu. The big screen is a problem for dimness and edge-to-edge brightness, but it should respond well to a digital beam. An indoor screen is porous to allow sound through, but that means that some light is lost. A drive-in screen is solid and should reflect light better. The brilliance of the digital illumination should also help counter chronic drive-in problems like fog, ambient light, moonlit nights, and some flaws on the screen.

The Goetz attendance flattening is part of a larger trend. The box office of 2011 has been weak, and for several years the total domestic admissions have hovered between 1.3 and 1.5 billion. Box office takings are up chiefly because of raised ticket prices, particularly for 3D and Imax. Professional predictors are suggesting that this year’s ticket sales will end up about the same as last year’s.

It would be easy for us cinephiles to bemoan what happened between Sunday and Tuesday in Monroe, Wisconsin. We celebrate the look and feel of film, and we’d like to see old picture palaces become temples dedicated to 35mm. But we don’t pay the shipping and heating bills for those houses; we don’t dicker with bookers who won’t let us have prints when we need them. We like the idea of film surviving, but the practical people who actually deal with exhibition day by day can’t afford to satisfy our tastes.

And we purists would doubtless be scandalized at what film prints looked like when they made their way to the Goetz in the old days, six months or more after release. The Goetz Junior opened with Eddie Cantor’s Strike Me Pink nearly a year after it premiered in Manhattan. In April 1956 the Chalet was running a 1951 Roy Rogers movie. Take a time machine back to the 30s or 40s or 50s and you’ll probably watch a choppy, scratchy print. In comparison digital starts to look pretty good.

I’d like to see Duke succeed. Monroe’s theatre reminds me of the single screen of my childhood, Schine’s Elmwood in Penn Yan, New York. That theatre is long gone, so part of me hopes that somewhere a local movie house can still bring in the community–whether it’s showing film, 2K, Blu-ray, or vanilla DVD. When I was a boy, I wouldn’t have cared how those images got on the screen. In a town like Monroe, the theatre, and the neighborly spirit it represents, is as important as the emulsion. One item of evidence is my 1936 photo up top, taken from the Goetz website. Down past the Hollywood Inn, which I wish I could visit now, maybe you can make out the Goetz marquee: TODAY 2 BIG FEATURES IN GERMAN.

Duke closed out his 35mm shows on the worst weekend exhibitors had seen since fall 2008. Will digital bring Monroe area customers back? Once people realize that they will get high-quality presentation in their home town, perhaps they won’t drive half an hour to Freeport or an hour to Madison. But best not to prophesy. Duke realizes he’s taking the same sort of risk that Leon and Chester took when they built the Goetz at a price of what would be $1.7 million today. “My motto,” he says, “is go digital or die.”

This is the second in a series of entries on the conversion of filmmaking, distribution, and exhibition to digital formats.

Leon Goetz is also credited with producing at least two films, Ten Nights in a Bar Room (1931) and The Call of the Rockies (1931).

I thank Duke Goetz and Mrs. Robert Goetz for talking with me about the past and present of the family business. Other information comes from volumes of The Film Daily Yearbook and issues of The Monroe Evening Times of 1 September 1931; 23 December 1956; 22 October 1981; and 15 May 2001. Also very helpful was Pictorial History of Monroe, Wisconsin, ed. Matthew L. Figi (Green County Historical Society, 2006), supplemented by some discussion with Matt. Thanks also to the staff of the Monroe Public Library.

For better versions of the picture at the top of this entry and the frontal view further down, along with other high-quality images, go to the historical page of the Goetz Theatres site. A chronology of the Goetz Theatres is on this page, and some shots inside the booths at the Goetz 2 and 3 are here.

P.S. 15 December: Thanks again to Matt Figli, who spotted some inaccuracies in my account of Monroe’s history. They have been corrected.

P.P.S. 28 December: Katjusa Cisar’s story in The Monroe Times today brings us more information on the Goetz, both past and present.

Pandora’s digital box: In the multiplex

Advertisement for NEC digital projectors, Variety July 2005.

ELECTRONIC CINEMA IN THE WINGS

Not only will [HDTV] usher in a new era of dramatically enhanced sharper-picture, improved color, wide-screen, stereophonic home TV, but HDTV will give rise to what’s already being called “electronic cinema”—high-definition video used to make 35mm quality theatrical feature films.–Variety, January 1982

FAROUDJA TOUTS VIDEO FOR BIGSCREEN

Faroudja and Videac seek to demonstrate that today’s technology makes it quite possible to display video images in a theatrical environment of a quality that can stand comparison with 35mm film. —Variety, June 1989

DIGITAL TECH POINTS TO PIX’ FUTURE

In the midst of a digital revolution that is embracing television, cable, and telephones, the movies certainly aren’t immune. Appearing soon in a theater near you will likely not be film at all but a digital projection that looks like the real thing. —Variety, May 1992

DIGITAL CINEMA HOVERS ON HI-TECH HORIZON

“I really do think at least a couple of the major players are pretty close.”–Variety, June 1995

WHEN PRINTS WILL NO LONGER BE KING

While the eventual replacement of 35mm projectors by video systems was seen as an inevitability—and a welcome one, at that—most agreed it was still far in the future. But after seeing six state-of-the-art systems beam images onto a 40-foot-long screen at the United Artists Denver Pavilions complex, many attendees agreed that the future is already upon us. — Variety, January 1999

Aug. 15, 2004: Using his computer keyboard and mouse, the president of top U.S. theater chain Regal/ Loews-AMC books the upcoming weekend’s films into his circuit’s theaters.

As he clicks on the titles (“Austin Powers 4: You Only Shag Twice,” “The Matrix III,” and MGM’s long-awaited “Supernova”) the films begin downloading via satellite to the circuit’s digital megaplexes around the globe. —Variety, August 1999

DIGITAL CINEMA’S PICTURE STARTS TO FADE

A few years ago, cinema operators were open-minded, but not any more. Now it’s clear that the first-generation digital projectors—brand-spanking-new equipment installed in 116 screens worldwide, out of an estimated 108,000 cinema screens globally—is rapidly becoming obsolete. — Variety Deal Memo, July 2002

AT LONG LAST, DIGITAL THEATERS

Finally. Digital cinema is here. No, really. . . . The conversion of of 35,000 US screens to digital projection can begin in earnest.

. . . . All six “Star Wars” films will be converted for 3-D re-release, perhaps as soon as 2007. —Variety, July 2005

DB here:

Reading things like this over the last couple of decades, I smiled patronizingly. The shift to digital, hyped from the start, sounded both inevitable and impossible. Even the ad for NEC at the top didn’t faze me. I’ve seen braggadocio before.

In my smugness I forgot that most broad changes take a long time to be consummated. Historian Jim Cortada writes that a new technology may wait as long as forty years before an industry decides to adopt it. I should have remembered that in cinema many hardware changes, such as color movies, took a surprisingly long time to become dominant.

Now everybody has woken up. We realize that we’ve crossed a threshold. Henceforth digital projection will be the norm.

Some numbers back up the impression. In December 2000 the world had 30 commercial digital cinema screens. In 2005 it had 848. At the end of 2010 it had 36,103—about thirty per cent of the total 123,067 screens. In North America, the jump was dramatic, from about 330 d-screens at the end of 2005 to over 16,000 at the end of 2010.

This year has iced the cake. In the UK, 80 % of releases were digital. At Cannes there were a great many digital screenings, even of films shot in 35mm. In Belgium the two major theatre chains, Kinepolis and UGC, went wholly digital. In Norway all 420 commercial screens were converted, partly because the government funded the changeover. Closer to home, the dominant chain in our region, Marcus Cinemas, went digital and fired its projectionists—ironically, just before Labor Day. My local theatres are junking their 35mm equipment. Roger Ebert recently posted a letter from Twentieth Century Fox announcing that “within a year or two” it won’t be sending out film prints.

Given all this, the newest predictions don’t look as Pollyannaish as the ones I listed up top. “Some time in 2013,” says a spokesman for the National Association of Theatre Owners, “all the [U. S.] screens will be digital.” Next year, half the screens in the world are likely to be. By 2015, predicts IHS Screen Digest, film-based projection will be defunct in commercial cinemas.

I’m not smirking now. Digital cinema is here.

The booth

“Here,” of course, is a place still in transition. I saw that back in September when I paid a visit to my local, an AMC multiplex in Fitchburg, Wisconsin. Its projection booth, a vast tunnel running almost the breadth of the building, reflected the changes in progress. Several 35mm projectors were still humming away, pulling the film from one big platter to another. There were some digital projectors too, one being the Sony SRX-R320.

You’ll notice the two lens housings on the right, suited to 3-D. Using these lenses for screening 2D films is a bone of contention in the current controversy about digital projection. (See the codicil for this entry.)

There was one Christie digital projector, run both from a computer and a touch-screen.

The heart of the system is the Digital Cinema Package (DCP), shown above. It’s a cute item, a little taller and skinnier than a trade paperback. It comes in a bright red carrying case padded with pink foam. Essentially, it’s a hard drive containing files for the image, sound, and subtitles, as well as files for playback, security, and encryption. The film is compressed; an hour-long movie at the maximum rate would take up about 115GB on a DCP. Trailers and specialized content, like Met Opera shows, come on their own DCPs.

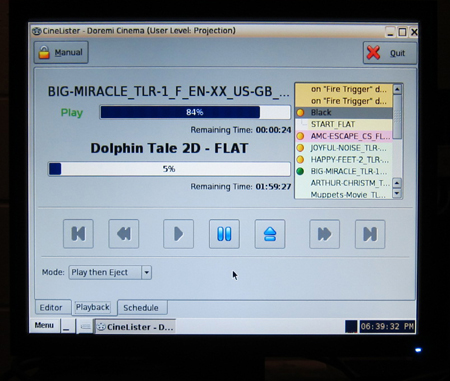

The DCP files have to be opened, with password keys supplied by the distributor. The files are then loaded into either a projector or a server in the booth. Loading can take several hours. A projector like the Sony can hold half a dozen or more features. Since the projectors are essentially big computers, the features, trailers, ads, and the like have to be arranged in a playlist, accessed by either a touchscreen, a laptop, or both.

The fear of piracy has kept back one early aim of the digital cinema revolution: Delivery of content via satellite or the Net. These are apparently too vulnerable to hacking or crashing. So the DCP is delivered the old-fashioned way, by courier services like UPS and FedEx. The decryption keys are sent by email or by a much older technology: the telephone. Often exhibitors and projectionists—sorry, Mr. or Ms. Screen Management System—has to phone somebody to learn the codes to tap in.

Turning points before the tipping point

The digital switchover seems sudden, but like most historical change there’s a story to tell about it. The digital changeover in movie houses was delayed by many factors, but the problems were solved, as usually happens when there’s money to be made and people are in the grip of the next big thing.

Here are four factors that, to my mind now, made the difference. They didn’t crop up in neat sequence, but they developed in an intertwined fashion before gathering in a knot in the last year or two.

1. The setting of standards

Standards are of immense value to the film industry. It’s to everybody’s interest to have movies run at the same rate, but if you think you can improve on 24 frames per second (sometimes 25 in Europe), you will have a long climb. (Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill have found this in arguing for higher frame rates.) Technological change in Hollywood consists chiefly of the Majors cooperating with each other to mutual benefit, while setting up barriers to entry that exclude outsiders.

For the most part, standards in film have been set not by trade associations or government agencies but by the major players: the technology suppliers and the studios. Innovations in sound, picture, color, and widescreen tended not to come from within the filmmaking companies but from outside firms and lone inventors, eventually to be accepted by the majors. Only then do the trade associations and other institutions get into the act.

The standards are often in flux, constantly adjusted to practical concerns. What, for instance, is the CinemaScope aspect ratio? Designed originally to be 2.66:1, twice as wide as the 1.33 format, it went to 2.55 and then to 2.35, partly because of Twentieth Century-Fox’s responses to the market. Later that standard was modified again, to 2.40. The Society of Motion Picture Engineers, which has historically tried to stabilize the technical standards, often played catch-up, refining or revising standards that were already common practice on the ground.

The real momentum for standardization comes when the American film studios, as an oligopoly, decide to throw their weight behind an innovation. This is what happened with the DVD and the Blu-ray disc (and may happen with higher frame rates for digital). Once the decision-makers have surveyed the range of options out there, usually offered by very big technology companies, there ensues a process of negotiation, testing, and horse-trading before a standard is arrived at. And even then the standards might be pretty flexible.

For digital projection, the oligopoly’s concerted effort began in 2002, when the six major studios formed a joint venture, the Digital Cinema Initiatives, LLC. As the studios in the 1920s had recruited the American Society of Cinematographers to test incandescent lighting systems, so they now had the ASC create material for testing digital projectors. The DCI also hired universities and private agencies to test the systems. Some interim documents proposed requirements, and the full set of specifications was issued in July 2005. This 161-page document has been revised, but it remains the bedrock for any manufacturer, theatre chain, or projectionist (defined in the text as part of the “Screen Management System. . . the human interface for the Digital Cinema System”).

![]() The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

The original document, available here, is a mind-boggler for anybody not familiar with the engineering of digital systems. It specifies image qualities, audio characteristics, metadata, encryption, and security parameters. Here’s a sample from the nineteen tasks assigned to the Security Manager (SM)—again, not a person but a program:

Secure Processing Block behavior and suite implementations shall permit the SM to prevent or terminate playback upon the occurrence of a suite SPB substitution or addition since the previous suite authentication and/or ITM status query. The SMs shall respond to such a change by immediately purging all content and link encryption keys, terminating and re-establishing: a) TLS sessions (and reauthenticating the suite), and b) suite playability conditions (KDM prerequisites, SPB queries and key loads). “Prepsuite” command(s) shall be issued per (9) prior to the next playback.

This is a far cry from what projectionists and theatre managers have traditionally known how to do. The opacity of the DCI specs may have the effect of disempowering traditional film workers and shifting their responsibility to the maintenance manager working for the manufacturer or some other third party. In any case, as had happened with sound and widescreen systems, the American film companies set the standards for the world.

The publication of the DCI report led to the exuberance in my last quotation at the start. With this in place, surely digital cinema had arrived in 2005 (along with the imminent release of all six installments of Star Wars in 3D). Yet a report last March found that most projectors currently in use weren’t fully DCI compliant; Sony and other companies came up with fully compliant equipment only this year. So thousands of projection systems were in operation outside the DCI standard, working under the rubric of “interoperability.” As usual in the film industry, practical demands outpaced standardization. 2011’s new lines of projectors from major providers are DCI compliant, which should attract exhibitors who were hanging back to see how all this got sorted out.

2. Convergence of hardware

A key condition laid down by the DCI was a requirement that digital exhibition be 2K or 4K resolution. That eliminated some systems outright, notably the unsatisfactory 1.3K format that had had some take-up in the US and had proliferated in foreign markets such as India (and are still flourishing there under the name of “e-cinema”). 1.3K systems were in the majority until 2005.

For 2K or 4K projection, Texas Instruments had already developed its Digital Light Processing system, consisting of thousands of microscopic mirrors, and this was adopted by three major manufacturers: Christie, Barco, and NEC. Sony developed its own system using modified LCD technology, claiming that only that can do justice to 4K projection. These four companies dominate the digital theatre market. All were producing machines in numerous models by the end of the 2000s.

China and Russia, both growing markets, proved particularly important, as their newly built theatres skipped 35mm altogether. The expanding markets gave the companies vast quantities of business; Christie reported that over 600 sites in Asia installed its projectors in 2009, while Barco claimed that it had 80 % of all installed screens in China. In Russia, of the 297 new screens added in 2010, 256 were digital. This surge from the periphery gave impetus to the US changeover as well, as brisk sales permitted the manufacturers to refine their systems and hatch new models.

3. The Virtual Print Fee

Historically, exhibition has been the most conservative wing of the film business. The theatre owner has the most to lose if a new technology fails to catch on. It was theatre chains’ reluctance to install magnetic-stereo sound systems that led Twentieth Century-Fox to redefine CinemaScope to 2.35, lopping off some picture area to make room for an optical soundtrack that would play on existing projectors.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

It’s expensive to retool a movie house for digital conversion. Each projector can run up to $100,000, and you need a server as well. In addition, the costs of maintenance are higher for digital; theatre owners initially claimed that they’d need up to $10,000 annually per auditorium.

The big three theatre chains in the US—AMC, Regal Entertainment, and Cinemark—control about 20,000 of the country’s 39,500 screens, and they were reluctant to embrace a technology that could cost them a couple of billion or more. If these dominant exhibitors wouldn’t jump in, no smaller circuits would convert. Moreover, the studios preferred a quick conversion. Distributing both 35mm and digital versions was costlier than either one alone.

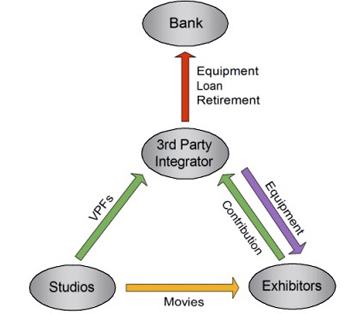

The solution was the Virtual Print Fee. Five studios agreed to help the big three finance the cost of conversion, to the tune of $1 billion. The VPF is a subsidy paid by the distributor. Under one common arrangement, it’s collected by an intermediary, known as a third-party integrator; the dominant integrators in the US have been DCIP and Cinedigm. The integrator loans the digital equipment to the theatre. For each booking the exhibitor makes, the film’s distributor gives a sum to the integrator (negotiable, but said in 2005 to be $1000 or so). But the VFP doesn’t cover the entire cost; the exhibitor has to chip in. Eventually the equipment is paid off and belongs to the exhibitor. (The accompanying diagram is taken from the informative site hosted by MKPE Consulting LLC.)

To speed up wide installation, most VPFs were set to expire at the end of 2012, although some are likely to be renewed or extended. Recently, Christie’s has initiated a VPF program aimed at independent exhibitors. Europe and Asia have VPFs and integrator go-betweens as well.

Most observers credit the VPF policy as a principal cause of speedier digital conversion, but there was another factor at work.

4. The killer app, 3D

The studios’ concerted offer of a Virtual Print Fee occurred in October of 2008, just as the world economy was heading down the drain. Credit was tight, and the rate of digital conversion was slowing. 3D came along at the right moment. Exhibitors learned that there was a line-up of big 3D films for 2009, all from the studios offering the VPF. A theatre that wasn’t set up for digital couldn’t play these titles.

Chicken Little (2005) showed the way, and in the following years a few films gave other promising results (Monster House, 2006; Meet the Robinsons, 2007). Concert films, especially Hannah Montana (2008), helped too. But Monsters vs. Aliens (2009), which played Imax houses as well as normal 3D ones, was a turning point: it grossed nearly $60 million in the US over its first weekend, more than half coming from 3D screens. The studios stepped up their production of 3D titles, from five in 2008 to eleven for 2009 and over twenty in 2010. Exhibitors saw that they could charge between $2 and $5 more for a 3D ticket, and this boost could help defray the costs of converting to digital presentation. Avatar seemed to seal the deal; it became the top-grossing film of all time (in absolute, not relative dollars), and after 47 days, over 80% of its $2.075 billion gross had come from 3D screenings.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

This year sees over thirty 3D releases. Kristin has pointed out that the calculations of 3D’s value to the box-office may be off-base. Still, the 3D initiative worked as a wedge prying open reluctant multiplexes. There are now over 22,000 3D screens worldwide, and in 2010, they yielded $6.1 billion in grosses–more than twice the 2009 figure. Hollywood should give Jeffrey Katzenberg (right) a medal for his insistence that this format was the wave of the future. Even if it’s not that, it was the Trojan Horse for digital projection.

I haven’t touched on other forces working in favor of digital theatres. Exhibitors were surely happy to embrace an automated system that would allow them to dismiss expensive unionized workers. Digital projection also opened up the possibility of using a venue for “alternative content”–pop concerts, opera broadcasts, sports events, and business meetings with snazzy presentations. Distributors gained as well. Besides saving money on prints and shipping—the public rationale for the switch—distributors could now monitor the number of screenings at any venue. A DCP-wrapped feature is set for only a certain number of runs. To extend the number of screenings, the exhibitor needs a new key code. This prevents off-hours screenings, a common practice of old-school projectionists. In addition, distributors suspected projectionists of video-recording prints or bicycling them for overnight telecine copying. (After Web 2.0, however, prime sources of bootleg copies have been workers in the industry itself.)

The past regained

Historians shouldn’t predict. I succumb sometimes, but I always regret it later.

Even professional predictors shouldn’t predict, as we see from a 2002 Credit Suisse First Boston report on digital cinema. That document declared that Eastman Kodak was the technological “winner” and would benefit from its “sensible business plan.” The report added that Kodak’s film business should face “minimal deterioration” from digital cinema. They valued Kodak’s Entertainment Imaging branch at $2 billion. Today Kodak’s entire company is valued at $900 million and its stock trades at $1.10 per share, down from the $30s in 2002.

So, no predictions from me. But warnings and worries? Yes, quite a few. Next time I’ll share some concerns about festivals, repertory cinemas, arthouses, colleges and community centers who depend on 35mm prints—especially older titles, our link to the history of the medium. Eventually we’ll get to archives, the repository of said history. I hope as well to offer some general thoughts about the redefinition of “film” in the high-def era.

In the meantime, let’s remember what was.

Alongside the 35mm and digital houses at the AMC Star Fitchburg 18 stands a very good Imax facility. If the digital gear shows us the present and future, I had the feeling that the monstrous Imax 3D projector, devouring two huge reels of 70mm film at the same time, was the world’s last movie machine.

Two fat ribbons, destined to intersect for an instant, whir past you, zigzagging around rollers, turning the room into a web of film. A pair of images snap into the gate. Each is sprayed with a puff of air. You must keep the film and lens clean; even a speck of dust looks like Rodan on the Imax screen.

Holding 35mm film in your hand is a pleasure, but 70mm is almost menacing. Even with 35mm, you need a loupe to see detail, but 70mm just boldly shows you everything, bright and crystalline.

The intimidating image suits the hardware that runs it. In the Imax 3D film projector, you see that mixture of enormity and delicacy, thrusting energy and exquisite precision, that characterized mass printing, tool-and-dye, and the rest of good old US industry since the nineteenth century. The whole contraption looks like a giant doing needlepoint. Yes, the sound system is digital, but you couldn’t find a more stubbornly old-fashioned way to display pictures—themselves big, palpable, and gorgeous. It puts you in mind of sledgehammers and nuts: All this just to show a movie? By all means.

This is the first of a series of entries reflecting on digital cinema.

Statistical and trend-based information in this entry came from back numbers of Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and above all IHS Screen Digest, the premiere source for media industry data and analysis. Most of the articles and reports I consulted are proprietary or available online only by subscription.

On the web, the site I mentioned above, run by the consulting firm MKPE, is an excellent general source on digital exhibition. For a superb introduction to the Digital Cinema Package, see this article by Arne Nowak. Box Office Mojo offers a useful chart of 3D releases. Go here for a Roger Ebert’s entertaining interview with Katzenberg, who even comments on cutting rates in 3D. Grady Hendrix offers a lyrical portrait of the endangered species of projectionist.

The controversy around Sony’s 3D lenses arose when 2D films were projected through them, leading to a loss of light on the screen. The primary article on the matter is Ty Burr’s piece. Jim Slater explains the task of swapping lenses in “The World of Sony 4K,” Cinema Technology Magazine (September 2010), p. 30. You can decide for yourself how difficult it is to change the lenses by watching this video.

For a historical account of how the studios and their affiliated organizations, like the Academy and the American Society of Cinematographers, have coordinated technological innovation with manufacturers and supply firms, see Parts Four and Six of The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, by Janet Staiger, Kristin Thompson, and me.

Jim Cortada provides an overview of how computers revolutionized several media industries in his indispensable The Digital Hand, vol. 2 (Oxford, 2006).

Thanks to Rick Reavey and Adam Hasz of AMC Star Fitchburg 18.

PS 3 December 2011: As is well-known, Peter Jackson is shooting The Hobbit at 48 frames per second and James Cameron is planning to shoot either 48 or 60 fps on Avatar II. They believe that the higher frame rate will improve the quality of 3D images. A recent article in the print edition of Screen International (I don’t find it online) indicates that DCI standards don’t specify 48 fps for 3D, and that currently available projectors don’t permit it. The projectors can be adapted for it, but it probably means 2K rather than 4K resolution in the screening. See Adrian Pennington, “Life in the Fast Frame,” Screen International (25 November), 8.

PPS 3 December 2011: Here’s an item on Creative Cow by Doug Trumbull that addresses some issues in digital projection and discusses, yes, frame rates. Thanks to Stew Fyfe for the tip.

On your left, the past: A person and a film. On your right, the future: A black box.