Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Wesworld

DB here:

Wes Anderson is back on our blog.

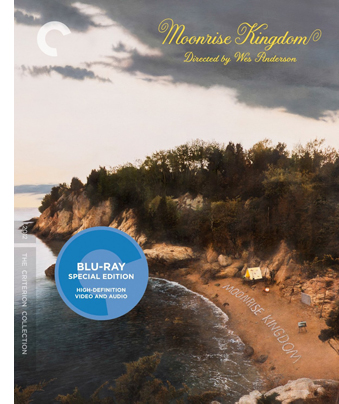

I composed a 2007 entry that tried to trace the stylistic tradition he belongs to (sloganized as “planimetric” staging and “compass-point editing”?). In 2014 the multiple aspect ratios of The Grand Budapest Hotel grabbed my attention. That essay, revised, was included in Matt Zoller Seitz’s anthology on the film, duly teased and announced here. At greatest length, another 2014 entry offered some thoughts on Anderson’s standing as an auteur through an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom (2012).

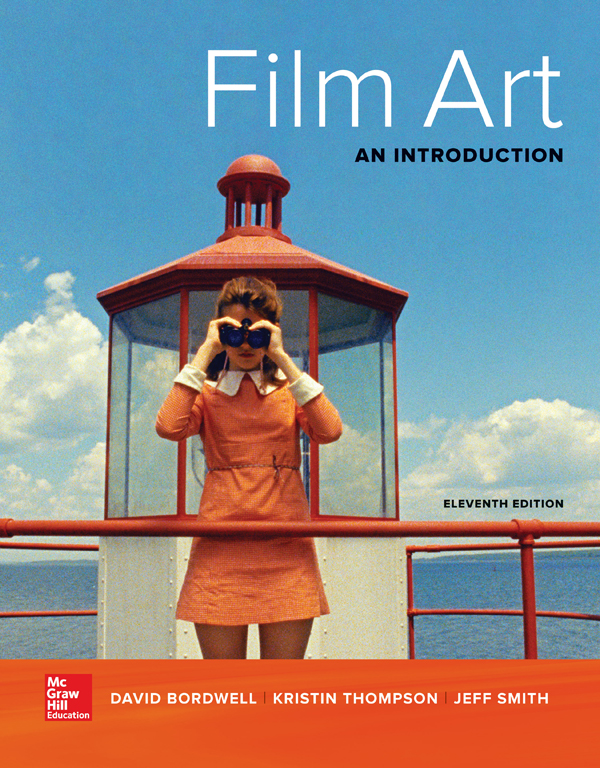

The film has worked its way into the eleventh edition of Film Art: An Introduction, forthcoming in January. In Chapter 11 an analysis of Moonrise Kingdom joins discussions of films by Ozu, Hawks, Hitchcock, Vertov, Scorsese, and other major directors. Moonrise Kingdom, I think, a film that will have lasting interest for young viewers and filmmakers, and it’s a fine vehicle for teaching principles of narrative and style.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

Since then I’ve learned more, thought more, and seen more. Specifically, I’ve seen Moonrise Kingdom in the gorgeous new Criterion Blu-ray release.

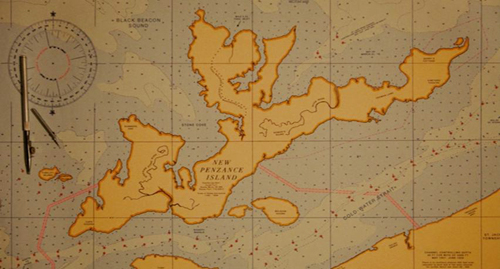

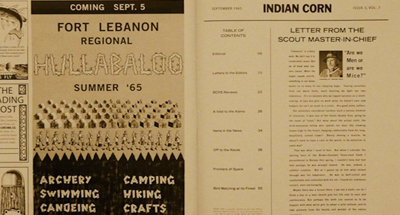

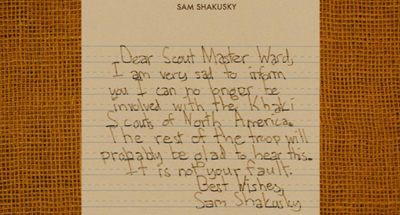

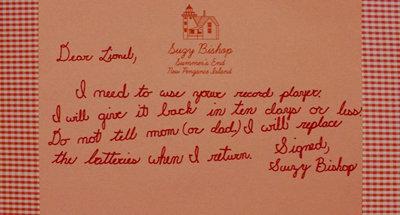

That release bundles in the sort of auteur artifacts my blog entry talked about. The purchaser gets a map of New Penzance, an invitation to the 1964 Noye’s Fludde performance at St. Jack’s, rather unflattering snapshots of the characters, and a postcard of the island ensemble (minus Social Services and the phone operator). On the disc we get Edward Norton home movies (as casual as anybody else’s, but showing some ingratiating behind-the-scenes stuff), some Bill Murray riffs, a brief making-of, and other snippets. The booklet, modeled on the Scouts’ magazine Indian Corn, includes a brief, sympathetic essay by Geoffrey O’Brien and reviews by kids.

A kid also conducts, if that’s the word, the extremely free-form commentary track on the disc. Young actor Jake Ryan, who plays one of Suzy Bishop’s brothers, sort of oversees chat among Anderson, Criterion leader Peter Becker, and participants in the production. Those last are brought in via phone calls. There are bathroom breaks, discussions of San Francisco Chinese restaurants, a Mozart piano performance by Jake, and a moment in which one discussant is accused, doubtless unjustly, of falling asleep. The whole enterprise, cut down from a five-hour marathon, will probably enchant Anderson devotees while giving new ammunition to those who find those admirers nuts, or worse. For my part, I found that Edward Norton and Bill Murray shared some worthwhile bits of acting craft, and Anderson gave some interesting information about the production.

Anderson adepts don’t need me to urge them toward this disc and its accessories. Today I want to think some more about this movie, which after two more viewings hasn’t lost any of its fascination for me. I’ll be concentrating on what it shows about worldmaking on the screen.

Departures, minimal and more

If you stripped off all the enticing elements like the toy lighthouse and the Khaki Scout badges, the gnomelike narrator and the interjected postcards and the implausibly perched treehouse, what do we have? In its bare bones, a pretty simple plot anatomy.

A couple in love, blocked by parental opposition, runs away. After an idyllic day and night, they are captured and separated. Then it all starts again, thanks to the miraculous conversion of some of the boy’s enemies, who decide to help him and the girl escape.

Again the couple flees, this time to be unofficially married. Pursued by parents and the authorities, the couple is trapped in a massive storm and is rescued by the kindly sheriff. They are united to live in a more-or-less tolerated love affair.

Although these are primal patterns of engagement, Moonrise Kingdom wouldn’t claim much interest if this were all it offered, folktale-fashion. As usual in modern narrative, the real interest involves finer-grained plot developments, characterizations, and narrational maneuvers. So the basic anatomy gets flesh, nerves, muscles, and circulating blood. Anderson and co-screenwriter Roman Coppola give us well-defined characters, dramatic situations, and secrets and mysteries and suspense. They play with time and viewpoint, build suspense, trigger surprises, and wrap things up with unexpected neatness. Several of these tactics I tried to chart in the 2014 entry.

Anderson and Coppola could have stopped there, but they didn’t. They went on to invent a world.

You can argue that this world’s main purpose is to distract us from the simple flight/pursuit/capture/rescue dynamic of the basic story action. But I’d argue that the final film benefits from fleshing the core action out in a way that situates it in a unique milieu. There’s also the point that worldmaking is no small achievement. Your task as a storyteller, George Lucas once noted, will change when you have to figure out what your character’s fork looks like.

Take the three dimensions of narrative I sketched out here and here—story world, plot structure, and narration. For some of us (I include myself) genre-based narrative has creative, even experimental possibilities along all those dimensions. Crime fiction, including mystery and suspense tales, can become a laboratory for experiments with plot structure and narration. Connoisseurs of thrillers and detective stories know that they must read warily, for the author is often trying to deceive and mislead. My entries on Side Effects and Gone Girl afford some examples of the process.

Fantasy and science-fiction can experiment with plot and narration, as do Blade Runner and Source Code, but those genres are more typically straightforward along those dimensions. Historically, their core appeal has relied mostly on creating unique story worlds. A prime attraction of Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings is the sense of an alternative realm teeming with unique creatures moving among unknown territories. But creating a distinctive story world puts demands on the storyteller.

We have an indefinite number of default values that are in place as we encounter any narrative. For one thing, we assume that the world we encounter there will be almost entirely like our own. Unless we’re told otherwise, we’ll assume that Sherlock Holmes can bleed.

Narrative theorist Marie Laure-Ryan calls this the principle of minimal departure. With secondary world tales, we move toward maximal departure. When a narrative world diverges drastically from ours, as those in fantasy and science-fiction do, we need a lot more extra information—about how these robots are related to their masters, about why the dragon has been sleeping for so long, about why it always seems to be raining in Blade Runner’s Los Angeles. The storyteller, in his or her own voice or via character dialogue, must spell out these minutiae.

But not all of them. Inevitably there are some unfilled spaces. Something always is left untold. As a storyteller, you know that every character comes trailing a backstory that can be expanded or revised (maybe in a sequel). In addition, your world gains solidity if you hint about tales yet to be told, as Dr. Watson alludes to the still-unwritten case of the Giant Rat of Sumatra.

What the author leaves blank others can fill in. As the internet has shown dramatically, fans can take up the job of adding to secondary worlds. They can offer their own versions of adventures in the realms of Star Trek, LotR, and other fictions. True, nothing stops you or me from writing new adventures of Sam Spade or a sequel to Rebecca, but you probably won’t be enriching the characters’ milieus with fanciful creatures or gadgets or foliage, let alone entire planets.

Several big Hollywood franchises have embraced the idea of secondary worlds, but independent cinema largely has not. Indie films tend to be modest, realist exercises that tell their stories and stop there. Part of their raison d’etre is to be different from the fantasy and science-fiction epics blasted at us by the studios. So melodramas and thrillers, biopics and anecdotal character studies, don’t by and large traffic in parallel worlds. The sequel, a standard narrative unit for worldmaking fiction, is rare in indie cinema, and even then it tends to be of a realist tenor, such as Linklater’s Before/After series. When fantasy enters an indie film, as in Being John Malkovich or Beasts of the Southern Wild, it tends to consist of one adjustment of the principle of minimal departure, not a drastic overhaul of the story world.

Now we can get a better sense of the originality of Anderson. Moonrise Kingdom, like The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou, Fantastic Mr. Fox, and The Grand Budapest Hotel, presents itself as a richly realized parallel world. The classic comedy plot of lovers opposed by parental authority plays out in a densely furnished alternative realm derived from our own, but with its own peculiar features.

The uses of reenchantment

My 2014 blog entry took this parallel-world project as a valid one and defended Moonrise Kingdom against charges of preciosity and twee. I suggested that the film had affinities with a tradition of fantasy going back to Lewis Carroll, James M. Barrie, and G. K. Chesterton. In the back of my mind I had longer-term influences as well, such as stories of Atlantis and of course Gulliver’s Travels.

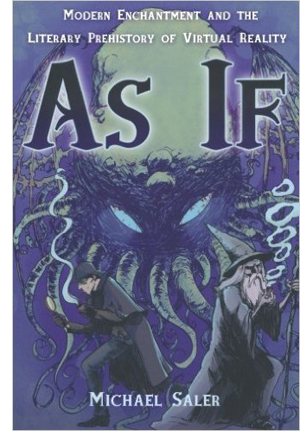

Since then, I’ve read Michael Saler’s excellent 2012 book As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Saler argues that the impulse toward fictional worlds in contemporary mass media and video games back to various strands of literary culture in the nineteenth century. He traces the development of a new kind of fiction: fantasy worlds rendered with the detail pioneered by emerging realist schools of writing. Poe and Verne were early sources, but the “New Romance” launched by Stevenson with Treasure Island (1883) and H. Rider Haggard with She (1887) crystallized the idea of imaginary lands that could be filled out in unprecedented detail. Stevenson’s and Haggard’s successors realized that maps, footnotes, news stories, eyewitness correspondence, and illustrations of artifacts could give pure fantasy a sense of solid reality.

Since then, I’ve read Michael Saler’s excellent 2012 book As If: Modern Enchantment and the Literary Prehistory of Virtual Reality. Saler argues that the impulse toward fictional worlds in contemporary mass media and video games back to various strands of literary culture in the nineteenth century. He traces the development of a new kind of fiction: fantasy worlds rendered with the detail pioneered by emerging realist schools of writing. Poe and Verne were early sources, but the “New Romance” launched by Stevenson with Treasure Island (1883) and H. Rider Haggard with She (1887) crystallized the idea of imaginary lands that could be filled out in unprecedented detail. Stevenson’s and Haggard’s successors realized that maps, footnotes, news stories, eyewitness correspondence, and illustrations of artifacts could give pure fantasy a sense of solid reality.

Admirers of these romances, Saler suggests, cultivated a complex frame of mind. They knew at bottom that it was all fiction, but they also enjoyed the imaginative freedom of a new game. They conceived a world that was as tangible as ours but still harbored the power of magic.

The imaginative exercise might vary. For extreme fans of the Sherlock Holmes saga, the task was to pretend that Arthur Conan Doyle was simply Dr. Watson’s literary agent, and that Holmes, Watson, Moriarity, and all the rest were living humans. Watson’s records of Holmes’ achievements became a sort of documentary scripture that had to be scrutinized for what it hinted at or left out. For admirers of Tolkien, engagement involved acquainting oneself with the encyclopedic variety of cultures, creatures, folklore, languages, and landscapes of a truly parallel world. What Tolkien called the legendarium presented as daunting a mythology as any discovered by a real-world ethnographer.

The broad social function of this trend, Saler argues, was to reenchant modern life. From geology to biology, from astronomy to psychology, turn-of-the-century science had blown away many dogmas. The spirit world was shrinking. The modern task of turning mysteries into puzzles for the rational intellect had begun. The “as if” invitation of virtual worlds gave both creators and consumers a way to exercise their minds in freer ways. Writers and readers could cultivate what Saler calls “animistic reason,” a rational scrutiny of what was there, but one fueled by imagination. As he notes, even that paragon of logic, Sherlock Holmes, relies on intuition and insight.

From this standpoint, Moonrise Kingdom reveals itself as part of a richer tradition than I’d realized. Its parallel world still seems to me to radiate the fairy-tale qualities of Carroll, Chesterton, and company, given some absurd twists; but now I see the emphasis on documentation, all the maps and letters and lists, as owing something to the New Romance. The film is something like a scrap-album version of a story. At the same time, the wondrous qualities of Anderson’s tale—not least, Sam’s survival of a lightning bolt and the miraculous rescue of the couple by Captain Sharp—carry, at least for me, some of that reenchanting of the everyday world that Saler finds in this tradition. Above all, we learn, as always, that things we think are very modern turn out to be new variants on something that went before. In Moonrise Kingdom, Anderson updates a nineteenth-century version of magical realism.

How to make a world

In my earlier entry I talked about how the worldbuilding enterprise fits snugly into modern cinema’s demands for both authors and brands. Anderson’s typical strategies of style and storytelling set him apart from his peers artistically, but they also offer entry points for merchandising and fan appropriation. What’s especially likable is Anderson’s embrace of the DIY aesthetic, as both he and his fans practice it. Unlike Lucas, who polices amateur Star Wars tchotchkes, Anderson encourages his admirers to spin their own riffs on his work.

Yet worldmaking is more than franchise branding. Saler’s As If, a work of cultural history, doesn’t try to analyze the literary strategies of the individual works very much. I want to ask: What does this creative option commit storytellers to? And how does Moonrise handle the challenges?

Most basically, the storyteller has to teach us the rules, big or small, that govern the world. Is it a kingdom, a post-apocalypse wasteland, or a world at war? This process goes easier if the imaginary world is a model world, a sort of schema we can fill out because it fits into a general concept we already have. If this is a kingdom, as Alice’s Wonderland partly is, then we can grasp the presence of Kings, Queens, aristocrats, soldiers, and beheadings. If it’s a wasteland, we expect something more like a world of nomadic tribes, with the absence of law producing scavenging bands and violent clashes. If an alternate world embodies one or more conceptual schemes we already know, we can learn our way around this new one faster.

The source schemas needn’t of course be absolutely real, just conceptually familiar. So the kingdom of Alice’s Wonderland is partly defined by the iconography of chess and playing cards. Likewise, our knowledge may not be wholly historical. Blade Runner’s LA is 80s Tokyo gone grubbily high-tech, but it’s also derived from the iconography of film noir. An idea of civil war informs Game of Thrones, with its borrowings from various phases of European history, but it seems likely that viewers’ familiarity with board games and role-playing games also clarify the forces in contention. The showrunner David Benioff tagged Game of Thrones “The Sopranos in Middle-Earth,” and this suggests how different schemas, real or fictional, can cooperate to distinguish a model world.

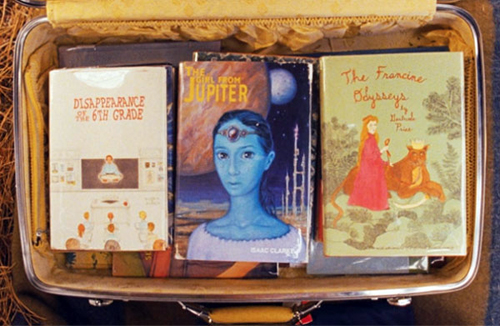

In Moonrise Kingdom, several schemas blend nicely to help us grasp the outlines and let the tweaks stand out. There’s the social situation of early adolescence, defined by family (or foster care, as in Sam’s case), schooling, and summer vacation. There’s the girl’s love of books with active heroines, a world counterposed against that of the boy scouts, with their ritualized adventures. Geographically, there’s the upper-coastal island that might be off Rhode Island, subject to tides and storms and inhabited by mostly upscale white folks. All these schemas and more are blended through the schema of “summer vacation,” a period where kids want to have adventures. Given our familiarity with these schemas, we can hook into a world of nerdish scout badges for Leaf Inspector and H2O Purifier, of slightly underscaled lighthouses, and a social worker named, by metonymy, Social Services.

An alterative world, by exaggerating a schema we already possess, can comment on the target world. Alice’s Wonderland satirizes the bloated capriciousness of the English aristocracy, and the Mad Max films suggest that increasing reliance on technology (i.e. oil-dependent machines) will paradoxically drive us backward to barbarism. In Moonrise Kingdom, probably most viewers would say that the summer in New Penzance provides a microcosm of the frustrations and disappointments of twelve-year-olds misunderstood by parents, teachers, guardians, peace officers, and other kids. By showing Sam bullied by other foster boys, as well as by the Khakis, I was reminded of my own stay in the Scouts. When the Scoutmaster’s back was turned, it all seemed merely a rehearsal for high-school thuggery.

Here’s another advantage. By mapping a schema we already know onto this new territory, we can appreciate not only the similarities but the novelties, the items that the storyteller has created to make this realm unique. In some cases, these novelties can be fairly narrowly focused. The Holmes saga emphasizes recurring characters and the furnishings and routines of the Baker Street household (keeping shag tobacco in a slipper, summoning the Irregulars). Beyond this perimeter, we are in more or less realistic 1890s London. Alternatively the infilling can be much greater, as with the imaginary landscapes and folkways of Middle-Earth. Here the creator earns esteem not only as a storyteller but as a sort of secular demiurge able, as the Romantics said, to echo the power of the Almighty. It’s easier to destroy a world than to make one.

Here’s another advantage. By mapping a schema we already know onto this new territory, we can appreciate not only the similarities but the novelties, the items that the storyteller has created to make this realm unique. In some cases, these novelties can be fairly narrowly focused. The Holmes saga emphasizes recurring characters and the furnishings and routines of the Baker Street household (keeping shag tobacco in a slipper, summoning the Irregulars). Beyond this perimeter, we are in more or less realistic 1890s London. Alternatively the infilling can be much greater, as with the imaginary landscapes and folkways of Middle-Earth. Here the creator earns esteem not only as a storyteller but as a sort of secular demiurge able, as the Romantics said, to echo the power of the Almighty. It’s easier to destroy a world than to make one.

Accordingly, much of the admiration fans feel for Anderson comes from the fact that it’s idiosyncrasy all the way down, from geography and architecture to books, games, toys, indicia, and the like. Other films give us fake locations, but he interpolates fake maps and a fake guide.

The pleasure is one of unnecessary abundance that suggests new stories. The detail that isn’t dwelt on—the kitty casually carried in a fishing creel or the needlepoint landscapes that preview the film’s locations—suggest that we could turn a corner and simply find more unpredictable stuff filling this world. What’s the story about One-Eye’s bandage? Anderson talks of wanting to suggest that the Bishop attic should entice us toward other narrativess:

I also had the idea that maybe the house could have the atmosphere of a rickety old place in some book where the kids go up into the attic and reach through a broken board and find a fragment of a forgotten map and set off on an adventure—that it could have that sort of feeling.

As with Doyle’s Giant Rat of Sumatra, there would always be more to find if we could probe this world more fully. The best Almighty is one that leaves some corners of creation to be imagined.

Imaginary gardens with imaginary toads in them

The overabundance of detail is open to the charge of fussiness and self-indulgence. Isn’t packing so much in just a matter of being cute? The infilling is particularly vulnerable because it often seems merely decorative. Details that affect the story action hardly count as details any more: the Ring in The Lord of the Rings is central to the action, while the Evermind flowers aren’t. Once we get beyond purely narrative functions, I think that the details of richly appointed worlds can fulfill at least five other purposes.

First, there’s realism. The doings on New Penzance and environs aren’t wholly cut off from the real world. The action is set in 1965, and the clothes, furniture, portable record player, and other furnishings match the period. To take one detail: the Françoise Hardy tune “Le temps de l’amour” anchors Suzy in a particular taste culture, that of American girls and women who took up yé-yé, Sylvie Vartan, and Salut les copains music rather than the Beatles or the Stones. American cinephiles are probably most familiar with this taste culture from Godard’s Masculin-feminin (1966).

It seems that an urge toward realism drives Anderson to build his micro-world. He speaks of creating all the props: “All these things just take forever, but I feel like even if they don’t get that much time [on screen], you kind of feel whether or not they’ve got the layers of the real thing in them.” It’s striking that he uses the same word that Ridley Scott did in calling Blade Runner‘s milieu a “seven-hundred-layer cake.”

Then there’s allusion. Details that are only minimally realistic can instead point outside the film. We’re familiar with more or less public movie allusions, as when a TV playing in a bar is running a film that comments on this one. Anderson seems not to have intended the title to be an allusion in this sense, it functions as one. It brings to mind Borzage’s Moonrise (1948), a hallucinatory noir centering on a backwoods manhunt for a less-than-guilty young man and the woman who loves him.

The name of Sam’s chief Scout tormentor, Redford, is more straightforward, as is the island called Penzance, which evokes the Gilbert and Sullivan operatic fantasy of blocked romance and also comic policemen.

One task for critics is to expose to our view the more hidden allusions, like the fact that the church on St. Jack Wood Island isn’t only a play on St. John’s Wood but refers to a favorite film of Anderson’s, Peter Bogdanovich’s Saint Jack (1979). Even if a viewer doesn’t know the allusion, she can suspect that any highlighted detail might like an Advent calendar window be hiding a citation.

The real mark of a richly realized world, as I’ve suggested, is a plethora of details that proliferate beyond the needs of realism and the temptations of allusion. So sheer density is another function. Moonrise Kingdom has to obey the principle of minimal departure, so perhaps the narrator is needed to explain the island’s geography. But in all the badges, books, and place names, the film supplies far more than the action requires. And such materials have been extended outside the film’s limits through the video extracts from Suzy’s books, the carefully printed collections of the Khaki buttons, and ephemera like those items collected in the Criterion package. Even the disc itself, with its little raccoon, is adapted to the story world. From this perspective, The Wes Anderson Collection, though a book, is exactly that: a gallery assembling items from the films’ distinct realms.

The real mark of a richly realized world, as I’ve suggested, is a plethora of details that proliferate beyond the needs of realism and the temptations of allusion. So sheer density is another function. Moonrise Kingdom has to obey the principle of minimal departure, so perhaps the narrator is needed to explain the island’s geography. But in all the badges, books, and place names, the film supplies far more than the action requires. And such materials have been extended outside the film’s limits through the video extracts from Suzy’s books, the carefully printed collections of the Khaki buttons, and ephemera like those items collected in the Criterion package. Even the disc itself, with its little raccoon, is adapted to the story world. From this perspective, The Wes Anderson Collection, though a book, is exactly that: a gallery assembling items from the films’ distinct realms.

Density for its own sake is part of the worldmaking project, but it accomplishes more. The effusion of such minutiae becomes an occasion for the filmmaker to display virtuosity, a zest for creating a consistent but unpredictable wash of detritus rivaling that in our world. Prodigality of invention, even when it gets a little obsessive, can be one mark of artistic quality. Joyce, Pynchon, Zola, Balzac, and other straining appetites invite us to appreciate how they’ve stuffed a wide canvas with minutiae.

For a narrative to create a secondary world, then, we need a fair amount of sheer stuff. In Moonrise Kingdom Anderson highlights the stuff through unusual film techniques. Not content to let us simply register props in the distance or on the margins, he gives them prominence. In other films, the notes and maps and book passages that characters examine would be presented in a naturalistic way, clutched in hands or seen through optical POV. Instead Anderson simply thrusts these things at us, perfectly framed and lit, like items in a gallery display.

We shouldn’t forget a fourth function of all this detailing and infilling. Details need not point outward—toward a real world, or to other narratives, or to a New Penzance of the collective fan mind. Details can work very traditionally to bind the tale together. They can function as motifs.

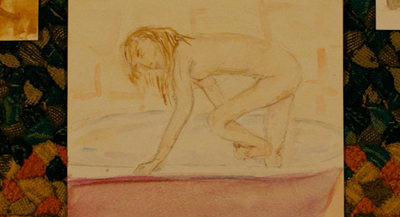

My 2014 entry points out many of these, but this time I noticed the glimpse we get of Mrs. Bishop washing her hair during one of the gliding surveys of the house in the opening credits. That angling of her torso over the tub anticipates one of Sam’s drawings of Suzy we see after Mrs. Bishop finds the lovers’ correspondence.

Again, the picture isn’t in Mrs. Bishop’s hand as she shows it to the men; it’s mounted on the wall along its mates, ready for a DIY gallery show.

When I first noticed the flaming motif on the Khaki unit’s motorcycle and helmet, I thought it was associated with Redford’s petty meanness. It is, but it’s also part of the Khaki Scouts’ insignia, as we glimpse early on when a scout irons his kerchief, here in the lower left.

When Redford’s patrol attacks Sam and Suzy, Anderson cuts to one of those vitrine-display images but very abstract and flashed in alternate colors. The flash-frames conceal the action. The promise of a fight given in the symmetrical-flame logo is fulfilled, but it’s amplified by inclusion of Suzy’s weapon, the forbidding scissors. She turns the Scouts’ logo and the scissors’ brand (Lefty™) into her escutcheon.

Motifs can help the other functions. The Khaki Scouts’ branded images suggest a parallel to Boy Scouts regalia, but they also make the Penzance story world cohere as its own place. At the same time, the fiery iconography suggests the aggression that several of the boys are ready to let out at any time, and Anderson stresses that as a thematic motif through his nondiegetic inserts during the skirmish.

The fifth function, recidivism, is in a way the simplest of all. Just as we might rewatch a mystery film to see how we were misled, people can rewatch Moonrise Kingdom to seek out the sorts of felicitous touches we’ve been considering. A world saturated with details invites us to revisit it. That’s what happened with me.

Britten for boyhood

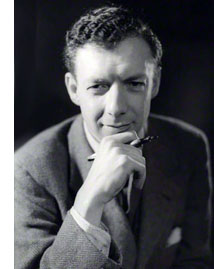

All these functions come together in one of Anderson’s most ingenious strokes, the use of the music of Benjamin Britten.

It’s an unexpected gesture of period realism from somebody of Anderson’s generation. In the 1960s classical concert music was central to intellectual culture in a way we can scarcely imagine today. Ives, Mahler, Satie, Shostakovich, and other masters were rediscovered, and avant-gardists like Varèse and Ligeti became familiar to a broad public. Imagine a time when filmmakers drew soundtracks from Penderecki (Kubrick) and Orff (Malick).

In this period, Britten achieved fame with LP recordings of his major operas, and he produced some indelible masterpieces. His War Requiem (1962, recorded 1963) became a best-selling album. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, often paired with Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, was recorded over a dozen times in the 1960s. The children’s pageant Noye’s Fludde (1958, recorded 1961) was designed for church performances of the sort we see in the movie (although probably few were as elaborate).

In this period, Britten achieved fame with LP recordings of his major operas, and he produced some indelible masterpieces. His War Requiem (1962, recorded 1963) became a best-selling album. The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, often paired with Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf, was recorded over a dozen times in the 1960s. The children’s pageant Noye’s Fludde (1958, recorded 1961) was designed for church performances of the sort we see in the movie (although probably few were as elaborate).

The Britten details amount to allusions too, both private and public. As a boy Anderson owned The Young Person’s Guide and with his brother sang in a performance of Noye’s Fludde. Just as important, if you had to pick a classical composer of the period who was centered on youth, it would have been Britten. Not only did he write a fair amount of music for young performers, but his later work drew ideas from pieces he wrote as a boy. The film includes a portion of one of these later recastings, the Simple Symphony of 1934. Set to Anderson’s images, the music evokes the brisk innocence of Sam and Suzy. So the allusions fit the subject and theme of the movie.

What about density? According to Anderson, Britten’s music permeates the movie. “The movie’s sort of set to it. . . . It is the color of the movie in a way.” Britten’s music isn’t incessant, but it is vividly presented in the story world during the big scene of Noye’s Fludde. Britten pieces are excerpted throughout the score as well. At the very end, the movie goes Britten-mad, first by playing the final fugue from The Young Person’s Guide (fulfilling the tease of the opening with Suzy’s brothers) and then, in the second part of the credits, applying Britten’s dissection of parts and choirs to Alexandre Desplat’s score.

The motivic uses of the Britten details are pretty evident. The Biblical flood in the church pageant predicts the film’s climax, and like the animals rescued two by two, Sam and Suzy will be saved. Less obvious is the motivic use of a lovely melancholy song from “Friday Afternoons,” one of several Britten pieces Anderson discovered while making the film.

In “Cuckoo,” a boy soloist and choir sings of the cuckoo’s waning stay: he comes in spring and flies away at summer’s end. We first hear the song during the low point of Sam’s fortunes. He has just been yanked away from Suzy and, as he is ferried back to camp, he’s told by Scoutmaster Ward that his foster parents have given him up.

The song’s text and plaintive melody evoke the end of the idyll and a bleak future for Sam.

But as we’ve seen, Sam and Suzy get reunited after the second cycle of escape/ chase/ capture. The song recurs in the epilogue as Sam, touching up his landscape painting, slips out of Suzy’s house to join Captain Sharp in the driveway.

At one point Sam has nothing; at the other he has everything. Now the song seems less a lament for a final fate than something less harsh: a lyrical envoi to a charmed summer that changed Sam’s life. The ineffectual father-figure Ward is replaced by the somewhat more competent Sharp, and Sam now has a future, with his mother’s pin worn discreetly alongside his Khaki honors. The cuckoo song gently enhances a scene that is at once an end and a beginning.

As for recidivism: Well, why not rewatch the movie listening for Britten’s music?

Henry Jenkins, a pioneering scholar of “participatory culture,” once pointed out a developing trend in recent popular media. Our creators seemed to have migrated from emphasis on the story (a singular chain of events, over and done with) to the character (a protagonist like Superman who can get involved in many stories), and now to the world (a realm in which many protagonists can interact, as in the Marvel Universe). Many fans want worlds they can redesign to suit their imaginations. But maybe we should sometimes leave those worlds intact.

I’m completely happy with tales that don’t proliferate across other platforms. I like characters who don’t carry the burden of multimedia backstories. But of course I’m open to worldmaking too. I’m especially open to it when an idea so identified with corporate branding and mass-production culture gets revamped by a temperament as unpredictable as Wes Anderson’s.

I’m as pleased as anybody when a swaggering space warrior lip-syncs “Come and Get Your Love” while using an alien lizard as a hand mike in Guardians of the Galaxy. Yet I’m even more appreciative when somebody finds a way to weave yé-yé and Benjamin Britten into an enclosed world I could never have imagined, and cannot improve. In place of the big worlds of Narnia, Middle-earth, the Marvel Universe and other macrocosms, New Penzance seems the right size for shades of ironic, tender feeling. Why should I want to rewrite this world? It’s enough to discover it, and explore it.

Thanks to Kristin and Brendan Colvin for good advice.

In the small-world spirit, Criterion offers close looks at some Khaki gear.

What do we call these relatively self-contained realms? I’ve used several terms. Tolkien may have helped the idea coalesce by coining the label “secondary world” in his essay “On Fairy-Stories”:

What really happens is that the story-maker proves a successful “sub-creator”. He makes a Secondary World which your mind can enter. Inside it, what he relates is “true”: it accords with the laws of that world. You therefore believe it, while you are, as it were, inside. The moment disbelief arises, the spell is broken; the magic, or rather art, has failed. You are then out in the Primary World again, looking at the little abortive Secondary World from outside.

Most of my information about Anderson’s creative process, including his interest in Britten, comes from Matt Zoller Seitz’s book-length interview The Wes Anderson Collection, particularly pp. 313-317. Anderson’s remark about the Bishop attic is on p. 300.

Marie-Laure Ryan discusses the principle of minimal departure in several publications, most fully in Chapter 3 of Possible Worlds, Artificial Intelligence, and Narrative Theory (Indiana University Press, 1991). An earlier and less technical version appeared in 1980.

Derek Jarman was inspired by Benjamin Britten’s music too; Jarman’s War Requiem (1985) is a sort of Wagnerian music video accompanying the original recording. It’s available for streaming, rental, and purchase here.

See Henry Jenkins’ Convergence Culture:Where Old and New Media Collide for more on popular-culture worldmaking. Henry blogs, indefatigably, at Confessions of an Aca-Fan.

George Lucas’s remarks about details and Ridley Scott’s about layers come from The Way Hollywood Tells It, pp. 58-60. Those pages discuss the trend toward worldmaking in mainstream Hollywood.

P. S. 5 November 2015: We have had some inquiries about whether the eleventh edition will be available for course use during the spring 2016 semester. McGraw-Hill’s intention was to introduce the new edition during the spring semester, for adoption for the fall, 2016 semester. Our editor, however, tells us that there are options for teachers who want to be early adopters and use the book in the spring.

Use of the print version for spring would be a tight squeeze unless your semester starts late in January. McGraw-Hills aims to have the SmartBook (i.e., the online ebook version) live on January 15th, the same date as the books should be on their way from the printer to the warehouse. It might take some time for books to ship once they get to the warehouse, so our editor recommends the SmartBook as the safest option for spring use. Early adoption assumes that instructors do not have lots of lecture PowerPoints and tests to update.

Usually, if the instructor works with the local MHE sales representative, the publisher can figure something out. If you are interested in being an early adopter, you should get in touch with your rep. If you don’t know who that is, you can find contact information here.]

Ritrovato 2015: Tributes to a great friend

Poster in memoriam Peter von Bagh, Bologna June 2015. Text: “For in and out, above, below,/ ‘Tis nothing but a magic shadow show/ Played in a box whose candle is the sun/ ‘Round which we phantom figures come and go.” “Only if I could screen ‘The Other Side of the Wind.'”

DB here:

The absence of Peter von Bagh, who died last September, was keenly felt at this year’s session of Cinema Ritrovato. It wasn’t just that Peter was no longer there, striding from session to session wearing a big smile and checking the schedule he carried on a small card in his shirt pocket. The loss was made palpable by the reminders of what he had done for world film culture. We know in the abstract that Peter was at once critic, historian, archivist, programmer, festival director, festival founder, and filmmaker. But all over the Cineteca Bologna and environs you find traces of his astonishingly busy life.

Walk into the book room and you’ll see a table groaning with massive volumes. A particularly bulky one is devoted to the Midnight Sun Film Festival he created in Sodankylä, Finland. There’s also a bulky autobiography. On the same table you’ll find DVDs of his films. Above the whole ensemble you’ll find the pensive poster that surmounts today’s entry.

Cinema Ritrovato is the world’s most comprehensive festival of restored and rediscovered movies. Mixing new editions of classics with heaps of films mostly unknown, it’s unique. It’s been called, not only by us, the Cannes of cinephilia. Peter was artistic director of the event during its years of intense expansion. It’s still growing, with bigger crowds and yet another screening venue added (making five in all, not counting the city’s central plaza for the big evening shows). Its size owes something, I think, to Peter’s enormous appetite for cinema–his urge to show as much as possible, to remind us of the majestic (but not solemn) tradition that cinephiles must treasure.

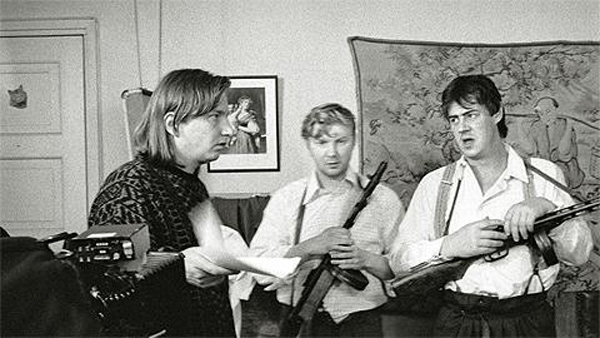

Books and DVD displays go only so far. Despite all these competing attractions, this year’s event has found plenty of occasion to celebrate Peter’s legacy. Threaded through this year’s vast offerings are tributes to the man who, with his colleagues Guy Borlée and Gian Luca Farinelli (with Peter, right, in 2008), has made the whole mad machine go. There are several screenings of his films coming up, and an evening on the Piazza Maggiore will be devoted to his memory.

Books and DVD displays go only so far. Despite all these competing attractions, this year’s event has found plenty of occasion to celebrate Peter’s legacy. Threaded through this year’s vast offerings are tributes to the man who, with his colleagues Guy Borlée and Gian Luca Farinelli (with Peter, right, in 2008), has made the whole mad machine go. There are several screenings of his films coming up, and an evening on the Piazza Maggiore will be devoted to his memory.

First off yesterday was a screening of Aki Kaurismaki’s TV film Les Mains sales (“Dirty Hands,” orig. Likaiset Kädet) from 1989. Peter had long wanted to screen it at the Ritrovato, and this rare item came forth as Kaurismaki’s homage to Peter. Shot in seven days on 16mm, it fits comfortably into the director’s personal world. Ironic humor mixes with dread, people in desperate situations act with surprising impassivity, and powerful figures bully and deceive pathetic, trusting innocents. A vaguely noir exercise shot in flat, drab color, Les Mains sales shows a political convert eager to become an assassin. At the start, his return from prison is interrupted by a flashback, complete with old-fashioned focus-pull transitions, showing how he got there. The usual Kaurismaki deadpan demeanor undercuts the brooding anxiety of noir, not to mention the source play. “It is Sartre read like a telephone directory,” Peter noted.

The screening was followed by “The 1000 Eyes of Dr. von Bagh.” Here several people shared memories of Peter. Gian Luca’s moving memoir of Peter in the catalogue was echoed in his opening remarks at the round table. Several people shared striking moments of what one called Peter’s “holy enthusiasm.”

The screening was followed by “The 1000 Eyes of Dr. von Bagh.” Here several people shared memories of Peter. Gian Luca’s moving memoir of Peter in the catalogue was echoed in his opening remarks at the round table. Several people shared striking moments of what one called Peter’s “holy enthusiasm.”

*Peter’s sardonic humor: He introduced his Third Reich series last year with the call, “Welcome, Hitler fans!”

*He explained why he brought 70mm equipment to Sodankylä for Play Time: “A film has the right to be screened as it was filmed by its author.”

*All cinephiles feel themselves somewhat out of step with normal living, noted Cecilia Cenciarelli, one of Ritrovato’s programmers. “Peter made this feeling of non-belonging noble.”

*Peter the educator warned how easy it was to show movies that would ingratiate the teacher with the class: “Always go against the tastes of the students.”

*Marianne Lewinsky, stalwart programmer of the Early Cinema events, observed Peter’s pleasure in selecting films: “He knew the joy of being judgmental.”

*Peter in a Russian museum: “Look, this painting is almost as good as a Tashlin movie!”

*Peter’s daughter Anna (above, with Cecilia and Gian Luca) recalls that Peter’s grandson, now talking, wants to fly to meet Peter. “I’d like to do that too.”

Antti Alanen, the preeminent Finnish archivist (and no mean blogger), will supervise the organization and presentation of Peter’s vast posthumous legacy of writings on cinema. During his lifetime Peter already donated his 8000 film books, heavily annotated, to the National Library of Finland, to be housed in a dedicated room in 2016. His archive includes interviews (most running 2-3 hours), and many manuscripts. He took notes during screenings and, unlike most of us who scribble by screenlight, immediately typed them up, embellished with ideas and associations.

Peter never stopped writing (often in bed, Anna says). There are several unpublished works nearly ready for the press, including books on Hitchcock and Welles, a study of comedy, a survey of cinephilia, and most daunting: a twelve-volume history of world cinema, one decade per volume. There are, Antti reports, passages ready to print, passages in a stream-of-consciousness mode, and passages in bullet-point outlines. They will find a home in the Website, “Peter von Bagh: The Memory of Cinema,” expected to go online, with English translations, in 2016.

Antti Alanen’s obituary, a thorough and moving career survey, is must reading. The meticulous David Hudson entry on Fandor gathers many tributes and other material. A book of admiring essays, Citizen Peter, can be ordered here. A brief review of Peter’s memoirs, published in Finnish in the year of his death, is here.

This site’s tribute to Peter is here. You can find references to him in our Bologna blog entries over the years.

28 June 2015, later: Thanks to Antti Alanen for corrections and elaborations of this entry.

Kaurismaki directing Les Mains sales.

Richard Corliss: Fulltime Critic

Mary and Richard Corliss, Ebertfest 2008.

DB here:

Parker Tyler called James Agee America’s biggest movie fan, implying that he was a lesser critic for loving movies. But Agee, who was often cast into despair by the films he met week by week, was actually in love with Cinema. From each release he sought glimpses of what he imagined movies could be, and so seldom were.

Tyler’s phrase might better apply to Richard Corliss, but in a deeply complimentary sense. Like his friend and occasional jousting partner Roger Ebert, Richard didn’t judge a film by whether it measured up to some ideal yardstick of the medium. He welcomed the movies—at Time, some 2500, between 1980 and now—as they came. He let his wide tastes, good sense, vast memory and knowledge, and breakneck gift for language decide what they counted for.

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

With Richard’s death we lose not only an effervescent critic. Under his stewardship of Film Comment (1970-1990) he helped found modern American film culture. Richard T. Jameson has eloquently recalled the Corliss era, when a magazine that had been committed to documentary and censorship debates became the paradigm of new ways of thinking about American and European film. Like Movie in England, it championed auteurism, and so it attracted great critics like Andrew Sarris, Robin Wood, and Raymond Durgnat. Yet Richard’s wide-ranging curiosity made Film Comment more pluralistic than its UK counterpart. It published reference-quality issues on animation, cinematographers, and set designers. In the days before the Net and specialized film books, cinephiles treasured these plump special numbers. The magazine ran historical and retrospective essays as well; refreshingly, not every piece was pegged to current releases. Richard gave us a new model of film magazines: richly designed, provocative (Durgnat especially), and sending the signal that everything cinematic could be studied.

When he went over to Time in 1980, that square magazine suddenly looked younger. With Richard joining art critic Robert Hughes, it became a source of lively and penetrating arts journalism. Both turned Timespeak into something fresh. Hughes pulled it toward the eloquent bluntness of the Anglo essay tradition, while Richard transformed the forced puns and slant metaphors into something sprightly. Sarris may have been his mentor, but the rat-tat-tat pileup of clauses (semicolons optional), the self-correcting afterthoughts (as if a nuance had just occurred to the writer), and a concentration on actors all seem to me indebted to Kael. On Edward Scissorhands:

Depp, who wears the hyperalert, slightly wounded expression of someone who has just been slapped out of a deep sleep, brings a wondrous dignity and discipline to Edward. Wiest does a delightful turn on the plucky, loving mothers from old sitcoms. The whole movie, in fact, time-travels between today and the ’50s, when every suburban house could be a quiet riot of coordinated pastels. But the film exists out of time — out of the present cramped time, certainly — in the any-year of a child’s imagination. That child could be the little girl to whom the grandmotherly Ryder tells Edward’s story nearly a lifetime after it took place. Or it could be Burton, a wise child and a wily inventor, who has created one of the brightest, bittersweetest fables of this or any-year.

Richard gloried in the emotional and visceral energy of popular cinema. He defended both porn and zany comedy. On the Big Loud Action Movie he could channel Teenboy patois:

Toward the start of Fast Five — fifth and best in the series that began with The Fast and the Furious in 2001 — Brian (Paul Walker) is in a freight train and Dom (Vin Diesel) is steering a 1966 Corvette Grand Sport alongside it. At the last possible moment before the train goes through a bridge over a river, Brian jumps from the train and lands on the Corvette, which Dom then drives off a, like, million-foot cliff. As the car plummets down the ravine, our guys jump out and land safely in the water.

That “a, like, million-foot cliff” is alone worth the price of the issue. For such reasons, I think that Richard might be the most imitated critic of recent decades. Every reviewer at your town’s weekly hip throwaway wants to write like this.

They mostly can’t. In an essay on Fulltime Killer, Richard compared Johnnie To’s cinematic output to A. J. Liebling’s boast: “I can write better than anybody who can write faster, and I can write faster than anybody who can write better.” It pretty much applied to Richard himself. He wrote about film, books, TV, travel, sports. Of the Bulk Producers we always ask, “When does s/he sleep?” With Richard we have to ask: “When did he pause?”

The Richard I followed most closely was on display in long formats. His book Talking Pictures: Screenwriters in the American Cinema (1974) made a stir that’s hard to appreciate now. Good student of Sarris that he was, Richard was an auteurist. He once tried to persuade me that Russ Meyer was at least as good as Minnelli. Yet his book called us to arms in a different cause.

The most difficult and vital part of a director’s job is to build and sustain the mood indicated in a screenwriter’s script—a function that has been virtually ignored while citics concerned with “visual style” trot off in search of the themes a director is more liable to have filched from his writers. …

When it comes to the mood men, the metteurs-en-scène, auteur critics start tap-dancing away from the subject. George Cukor is a genuine auteur; Michael Curtiz is a happy hack; Mitchell Leisen is actually despised by some critics for “ruining” films like Midnight and Arise My Love. Yet what Leisen and the writers of Hands Across the Table did to make that film the most amiable of thirties screwball comedies is a prime example of sympathetic collaboration. As with so many delightful comedies, it is the writers who create the characters and establish a mood in the first half of the picture, and the director who develops both in the second half. The story line of Hands Across the table isn’t flimsy; it’s downright diaphanous. . . .

Openly imitating Sarris’ catalogue The American Cinema, Richard’s book created an artistic genealogy of screenwriters, picking out the Author-Auteurs, the Stylists, and so on and then ranking them.. But where Sarris is synoptic, Corliss is dissective. Working at full stretch, he gives pages of close attention to particular films. His analyses of The Power and the Glory, The Lady Eve, and The Marrying Kind (“wavering between third-person omniscient and first-person myopic”) carry great intellectual heft, while Sarrisian potshots fly by. Reputations get deflated (Jules Furthman) or elevated (Sidney Buchman).

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

The other Richard book I hold close is his BFI monograph on Lolita, a sustained critical tightrope act. Trembling between whimsy, serious examination, and a Nabokovian delight in shameless cleverness (puns again), Richard gives us Kubrick’s film as filtered through Pale Fire. There’s a bespoke opening poem (shades of Shade) which is then glossed line by line in as digressive a manner as poor Kinbote pursues in the novel. Nabokov as Hitchcock, echoes of Goulding’s Teen Rebel, Shelley Winters maneuvering her cigarette holder “as a Balinese dancer would her cymbals”: every paragraph scatters pieces of candy.

Finally, something I return to often: Richard’s 1990 essay attacking (no politer word will do) TV movie reviewers. “All Thumbs: Or, Is There a Future for Film Criticism?” castigates the tribe’s superficiality, their canned brevity, their reliance on clips, and above all their encouraging people to believe in quick judgments. Stars, numbers, grades, and thumbs are too easy. Richard bites Time’s corporate hand, complaining about snack-sized opinions in People and Entertainment Weekly. Against this trend he speaks for longer-form writing, pointing out that Sarris, Kael, and others had their impact because they could surpass the word limits mandated for most reviewers. It takes time to develop ideas that are subtle. Obvious, maybe, but tell that to the young blogger who insisted to me that a review ought to take no more than 100 words.

Roger Ebert was a target of Richard’s piece, and he replied in a courteous counterblast. Yet the men were fast friends. Richard did friendship superbly, with an effusive generosity. Just out of college, I submitted a couple of articles to the new Film Comment, and to my astonishment Richard accepted them. As I turned more academic, I stopped offering pieces to the magazine, but Richard–who could easily have become a film professor himself–didn’t hold it against me. When I came to New York a few years later for a job interview that proved disastrous, Richard and Mary were the only friendly faces I encountered, and lunch at their apartment, larded with gossip, was the high point of that visit.

In later years I encountered Mary, mostly during our visits to MoMA, more than Richard. But every now and then I’d get another burst of gratuitous kindness. He reviewed my Planet Hong Kong in a funny online piece about how Hong Kong film takes the stuffiness out of anybody.

Even a relatively staid critic such as structuralist guru David Bordwell seems to be typing in his shorts, with a beer on his desk.

The last time I saw Richard was with Mary at Ebertfest in 2008. We had a diner breakfast, and Richard did a dead-on imitation of John McCain. I still see that smile—part devilish wise-guy, part nerdy enthusiasm, all glowing good humor. He was wearing goofy trainers bearing the logos of the Majors. They looked damn fine. We had a good day.

In an interview with David Thomson Richard recalls his life and the early Film Comment era. See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensitive appreciation, especially on Corliss’s mastery of the “long reported piece”–another point of contact with Agee.

Pure hits of storytelling: Westlake, Oswalt, Brackett

To Each His Own (1946).

DB bere:

Old friend and student, and proficient blogger, Paul Ramaeker writes:

I’m in the middle of Slayground now. In his Stark guise, Westlake as a writer really is as fearsomely directed and effective as Parker himself. I was thinking about the particular narrative pleasures here, like the way that delayed exposition works with the perspective switches between different sections. There is such precision to the way he builds certain effects in a systematic way, the way that we see Parker making plans, going around Fun Island doing things, but Stark not telling us what, exactly. I really did not get the logic of painting white circles in the house of mirrors–I thought of them as targets. Then, [spoiler excised] it makes so much sense, and becomes such a pure hit of storytelling, producing such a rush of pleasure in the reading.

That’s the way Donald E. Westlake worked. With Elmore Leonard and Ed McBain, he was one of the top crime-action writers to emerge in the postwar boom in paperback originals. He wrote a huge number of novels and some screenplays (The Grifters, The Stepfather). Several films, notably Point Blank, The Outfit, The Ax, and Made in USA, were taken from his books.

I’ve paid tribute to Westlake’s prose in this entry, but why not another Richard Stark passage to show how it’s done? Many of the novels start with a “When” clause, and upon relaunching the series in 1997, Westlake picked a dilly:

When the angel opened the door, Parker stepped first past the threshold into the darkness of the cinder block corridor beneath the stage.

The “When” clause hooks you in firmly, with the last word of the sentence locking in a framework that explains the opening. Here’s a simpler prototype Westlake himself picked, from Flashfire:

Parker looked at the money, and it wasn’t enough.

Anybody else would have cut the and and put in a period. This is better, I think because it quietly leads us to expect something more: a piece of action, a demand for more money. Anyhow, once we’re arguing about whether to put in an and, we’re talking about a real writer.

Slayground is one of those nifty experiments Westlake tried, this time putting two books in a divided POV arrangement. Both Slayground and The Black Bird begin with the same action, a getaway described almost identically in each one. Parker and his sidekick Grofield separate. One book follows Parker’s fate and other follows Grofield’s. I want to read both right now.

Before I do, though, I must signal (a) the University of Chicago Press’s brilliant idea of reprinting all the Stark novels; and (b) Levi Stahl’s wonderful compilation The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany. This consists of essays, memoirs, and interviews, running from 1960 into the 2000s. There’s even a recipe for tuna casserole contributed by Dortmunder’s girlfriend May.

Before I do, though, I must signal (a) the University of Chicago Press’s brilliant idea of reprinting all the Stark novels; and (b) Levi Stahl’s wonderful compilation The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany. This consists of essays, memoirs, and interviews, running from 1960 into the 2000s. There’s even a recipe for tuna casserole contributed by Dortmunder’s girlfriend May.

You learn a lot about Westlake’s life, of course; for one thing, you learn how Made in USA became unseen in USA for several years. A career-survey interview with a convicted bank robber is alone worth the price of admission. Stahl adds in fragments from an autobiography (“I was born in Brooklyn, New York, on July 12, 1933, and I couldn’t digest milk”).

Westlake was a thoughtful observer of his tradition, and he offers historical surveys and close readings of his hardboiled predecessors. He compares the prose of Black Mask writers Hammett and Carroll John Daly, and calls Raymond Chandler “a bookish, English-educated mama’s boy whose raw material was not the truth but the first decade of the fiction. This is not to denigrate Chandler, or at least not to denigrate him very much.” He praises Richard S. Prather for his “bonkers” style (“She was as nude as a noodle”) and registers his admiration for lesser-known contemporaries like Peter Rabe. He offers the best analysis of George V. Higgins I know, and his appreciation of Rex Stout warms the heart. Acknowledging the cunning ways that Stout hides plot gaffes under Archie’s patter, Westlake notes that perhaps Stout had “an affinity with those Indian tribes who deliberately include a flaw in their designs so as not to compete with the perfection of the gods.”

You also learn about the market. Westlake was a “fee reader” for Scott Meredith literary agency, one of the most prestigious around. He became a self-supporting writer in 1959, when he churned out over half a million words, all published. Writing an Avon paperback in 1960 would earn you $350, or $2800 in today’s money, but writing a serial for a magazine like Analog could net $450 for only 18,000 words. There’s a marvelous letter from that year in which a twenty-seven-year-old Westlake complains to a top publisher that he can’t get his best science fiction accepted, and that specific editors traduce the work of writers he knows. Stahl calls it “one of the most spectacular acts of bridge burning in the history of publishing.” Again, the author’s gesture recalls Parker’s chilly recklessness, but with jokes.

Popcorn and Red Vines

In his recent interview with the New York Times, Patton Oswalt included the Stark/Westlake Man with the Getaway Face as one of his favorite books of all time. It comes as no surprise that this gremlin polymath gets Stark/ Westlake. Those who know his fine Zombie Spaceship Wasteland will find more of the same in Silver Screen Fiend: Learning about Life from an Addiction to Film. As ZSW traced his early standup career and its intertwined relation to nerd culture, this quasi-memoir traces his early years in LA, writing for MadTV by day, honing his comedy act by night, and watching movies obsessively at all other times.

Despite his fondness for sitting far back (I’m down front) and mixing popcorn and Red Vines (I’ve been a Dots man for sixty years), Oswalt has left us the best memoir I know of being a sheer headbanging movie geek. A sort of nonfiction Moviegoer (Walker Percy), or a prose version of Cinemania, that disconcerting documentary in which everything reminds you of you, Silver Screen Fiend takes us into hard-core hell-for-leather filmgoing.

Despite his fondness for sitting far back (I’m down front) and mixing popcorn and Red Vines (I’ve been a Dots man for sixty years), Oswalt has left us the best memoir I know of being a sheer headbanging movie geek. A sort of nonfiction Moviegoer (Walker Percy), or a prose version of Cinemania, that disconcerting documentary in which everything reminds you of you, Silver Screen Fiend takes us into hard-core hell-for-leather filmgoing.

Filmgoing is the operative idea, not just film viewing. The book is set on the cusp of the DVD revolution, when the big-screen experience was so much better in contrast with VHS. There are descriptions of favorite theatres and fetishized experiences like Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast and a Hammer movie marathon. At the same time, this “sprocket fiend” was also a “stage ghoul,” trying to out-kill the other standup comics at the Largo. The two obsessions fed each other, as when Oswalt arranged public readings of the script for Jerry Lewis’ legendary Day the Clown Cried.

Throughout, the movie madness emerges as another channel for the explosive energy of a young man burning with ambition. At the theatre the splendid lunacy might be onscreen, or in the row behind you, where Lawrence Tierney was talking loudly back to Citizen Kane. The moment pulsates because Oswalt wanted to be in movies too, maybe as a character actor.

The book hits one of its high points in telling of his big break, in Down Periscope (1996), where he utters one line as the camera sweeps past him. He describes the process of filmmaking as hammering slowly away at the movie that isn’t there yet. It’s like “blasting a tunnel through a mountain. Or brushing every grain of sand off of a fossil. You attacked it relentlessly.” Oswalt squeezes pages of entertainment out of brooding over how to deliver “There’s a call for you, sir. Admiral Graham.”

Rest assured that every movie you see where an actor delivers just one line? They’ve put this kind of thought into it. Sometimes you can see it. Sometimes they can hide it. But everyone who gets in front of that lens has this inner conversation. I was having mine now. I was about to speak on film.

The moviegoing spiral ends on 20 May 1999, when Oswalt sees Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. The postmortem at a dinner marks the moment when the addiction subsides. “It hits me, sitting there with my friends, that for all of our bluster and detailed, exotic knowledge about film, we aren’t contributing anything to film.” He realizes that film should be one ingredient in the fuel for your life. “But the engine of your life should be your life.”

The epiphany is movingly described. (I wish I could say I’ve learned the same lesson.) Oswalt implies that film frenzy was a phase he went through, and now he’s grown up. (I wish I could say the same for me.) Yet I’m encouraged that Oswalt has not gone cold turkey. He’s passed from gourmand to gourmet. “My love of movies has turned into a love of savoring them.” And he can’t resist movie comparisons when describing that day-and-date release sometimes called Life. “Faces are scenes. People are films.”

In the back of Silver Screen Fiend are thirty-three pages listing all the films Oswalt saw across four years, along with the theatres where he saw them (New Beverly, Nuart, Tales Café et al.). Plenty of pure storytelling hits there. Far from makeweight, these pages create a new list of the kind he obsessed over in Danny Peary’s books. How many twenty somethings will start checking off the titles here?

The team

Charles Brackett, Gloria Swanson, and Billy Wilder.

On his very first night at the New Beverly, Patton Oswalt caught, and was caught by, Sunset Blvd. and Ace in the Hole. He mentions they were “co-written and directed” by Billy Wilder. He doesn’t identify the other half of the co-.

Nor do most people. In the case of Sunset Blvd., that fellow was Charles Brackett, who now stands revealed as not only a gifted writer but the Samuel Pepys of classic Hollywood. “It’s the Pictures That Got Small,” edited by Anthony Slide, is an absorbing chronicle of a tempestuous collaboration and the lifestyles of an era. A Harvard-educated WASP from Saratoga Springs, Brackett became a novelist, was made drama critic for The New Yorker, and sat at the Round Table with the likes of Woollcott and Parker. After some of his fiction was adapted to film, he moved to Los Angeles.

Brackett’s early work seems to have been undistinguished, though I’d defend at least Picadilly Jim (1936). Eventually he wound up at Paramount partnering with Wilder, and under the aegis of Lubitsch they clicked for Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938) and Ninotchka (1939). There followed Midnight (1939) and Hold Back the Dawn (1941) for Leisen, and Ball of Fire (1941) for Hawks–an early title of which, we learn here, was Dust on the Heart. Then came Wilder’s directed pictures, from The Major and the Minor (1942) to Sunset Blvd. (1950). Brackett was active in the Screenwriters Guild, became a producer, and continued to write scripts for his producing projects, including the delirious Niagara (1953) and the insufficiently delirious Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959). The Uninvited (1944), Brackett’s first solo production, remains charming, and To Each His Own (1946) is an interesting wartime weepie, with Olivia de Havilland massively frumped up. Miss Tatlock’s Millions (1948) also has its defenders.

“It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is a plump album packed with tiny but revealing snapshots. Although Brackett wrote entries nearly every day, he often made do with very brief mentions. Slide has edited them judiciously and arranged them chronologically, with some stitching to fill in events. A 1936 entry strikes a warm chord:

“It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is a plump album packed with tiny but revealing snapshots. Although Brackett wrote entries nearly every day, he often made do with very brief mentions. Slide has edited them judiciously and arranged them chronologically, with some stitching to fill in events. A 1936 entry strikes a warm chord:

I am to be teamed with Billy Wilder, a young Austrian I’ve seen about for a year or two and like very much. I accepted the job joyfully.

By 1943, Brackett is recording something much more rankling:

My consciousness that, after years of partnership, his first free act was to stab me in the back…my conviction that he’s turned into a second-rate director…my knowledge of the awful thinness of his mind, his stupidly limited interests. Alas, alas. And my knowledge that I am as little stimulating for him as he is for me.

During this supposed phase of creative drought, they were working on The Lost Weekend.

Apart from charting this bumpy collaboration, Brackett gives us a lot of information about how films got made. We learn about studio differences (Paramount less disciplined than MGM) and the importance of telling stories to others, face to face. I found plenty to feed my act-structure appetite. I was happy to find how often moviemakers went to the movies. Brackett attends dozens, both premieres and regular shows, and he records how easily screenwriters could summon up an older picture to be screened, even at a rival studio. This from 1947:

In the afternoon Billy and I saw Mr. Deeds at Columbia to check on certain similar situations in The Hon. Phoebe. It proved helpful and an excellent picture despite curious non-sequiturs and at least one horrible scene, Cooper absolutely charming. I could see some loathsome Capra characters beginning to unfold, but still in the lovely promising bud stage.

As a writer, Brackett is no less captivating than Westlake or Oswalt. We can rejoice in his Algonquin acidity.

Chaplin seems to me as repellant a human being as I’ve ever been in the room with—a thin, reedy voice, a show-off-hog face, and hysterical protestations of liberalism.

Jean Arthur called us, worried about the fact that there’s another woman in the picture [A Foreign Affair]. “I have sex appeal,” she said calmly, but inaccurately.

Greeted at the office by a nasty little note from Charles Jackson [author of the novel The Lost Weekend]. I had addressed him as “Birdbrain” in a telegram, something I could do to any friend—but an unsafe term to use to a man five feet tall.

And there are flat-out funny stories. Here’s just one, reported by Wilder.

[Von Stroheim] has always thought Swanson too young and desirable for the role of Norma. “Look at her,” he said. “I would like to fuck her now.” “I,” said Billy, “would rather fuck you.” “You have,” von Stroheim retorted.

If it didn’t happen, I want it to have.

In short, three more items for your shelf—repositories of good stories in themselves, prods and teases for your own thinking about story-making.

The University of Chicago Press has mounted a fine infographic on Westlake/Stark’s Parker novels here.

P.S. 19 January 2014: Thanks to David Cairns for correcting a slip. My original entry said that Brackett co-wrote Ace in the Hole with Wilder. Actually, the collaborators on Ace were Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman. Be sure to check David’s excellent Shadowplay site.

Down Periscope (1996).