Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.

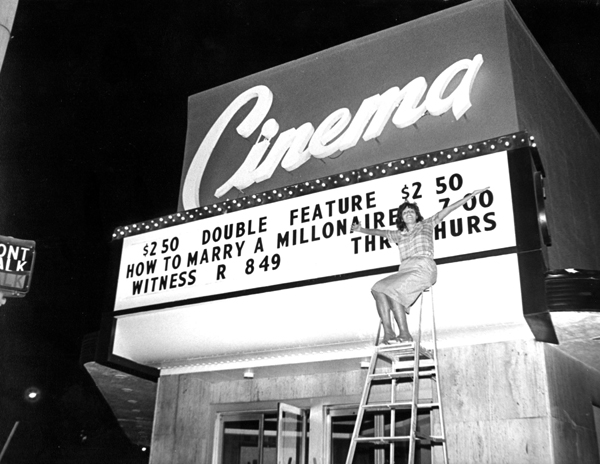

Cinema Theater, 1985, with JoAnn Morreale.

DB here:

For a while now I’ve been tracking the consolidation of digital cinema. After a blog series, I melded the entries with other information and created the e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. (To the readers who bought it, thanks!) Last year, in a blog called “End Times” I updated the information. Now we’re at post-End Times, I suppose.

David Hancock, who keeps meticulous account of these things, issued an IHS Technology Profile report on the state of things at end 2013.

*Of the world’s nearly 129,000 screens, over 112, 000, or 87%, are digital in some format. Most screens are compliant with the Digital Cinema Initiative standard used in the US, but India has pioneered the cheaper “electronic cinema” formats. Many of these e-screens will upgrade to the DCI standard.

*The UK and France have fully converted, along with most smaller European countries. Those countries benefited from various degrees of government support for the conversion.

*China now contains over half of the 32,642 digital screens in Asia.

*High concentrations of 35mm venues remain in Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and other areas with economic troubles. Other analog countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, lack public funding and contain mostly single-screen venues. The more multiplexes a country has, the greater the pressure to go DCI.

*In North America, out of about 40,000 screens, close to 93% have converted. That leaves about 3200 analog venues. It’s hard to know how many of those have closed or will close soon.

Most of the surviving analog sites, I suspect, are subsequent-run, like the five 35mm screens at our Landmark/Silver Cinemas ‘plex. And our Cinematheque and student-run Marquee continue to find and show excellent film prints. But clearly the moving finger has written. We at the University are striving for funding to make the changeover.

So too is a wonderful cinema I visited back in January. A family trip carried me back to my stomping grounds in New York’s Finger Lakes. I’ve already retailed some information about my hometown cinema, and a 1915 film that was discovered there. For now, let me tell you about a theatre I visited during a few days in Rochester.

Let George do it

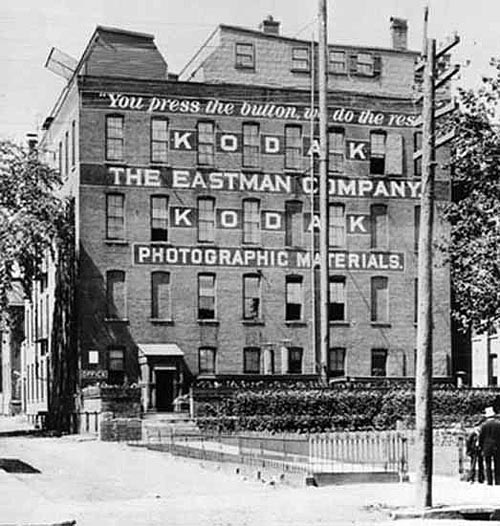

Eastman Company, 1892.

Before there was Hollywood film production there was New York film production. Before that, there was West Orange, New Jersey, where Mr. Edison and Mr. Dickson devised a movie machine. And somewhat before that, before movies themselves, there was Rochester.

Rochester was the home of the George Eastman company, founded in 1880. Eastman pioneered consumer still photography; he made up the word “kodak” to suggest the click of the shutter button. The company manufactured the flexible 35m film stock that formed the basis of the American cinema industry. Another Rochester industry, the venerable Bausch & Lomb provided camera and projector lenses, including those for CinemaScope in the 1950s.

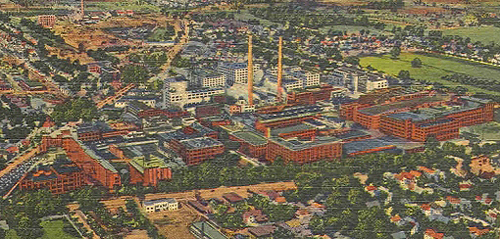

I suppose most people under thirty have never used a film-based camera, and for them the firm’s cheery yellow-and-red logo looks the way an ad for Packards looked to me in my teen years. Throughout most of the twentieth century, though, Eastman Kodak was one of America’s great technology firms. Here’s the Kodak Park facility ca. 1940.

The firm’s tragic decline will eventually get book-length treatments, but a short version is here.

Despite having invented the first digital camera, Kodak was overwhelmed by faster-moving competitors in that realm. As the firm mounted huge losses, the CEO, Antonio Perez, sought to leverage cash through Kodak’s many patents, but that tactic couldn’t stave off disaster. By 2011 Kodak stock was selling at about $1, down from the $25 it had been at when Perez arrived. In the same year, he was appointed to President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the following year.

Kodak has tried to reinvent itself, but its collapse has damaged Rochester badly. Growing up, I encountered in Kodak a supreme example of paternalistic capitalism; George Eastman even paid for dental care for all of Rochester’s children. In the 1980s over 60,000 people in Rochester worked at the firm; now fewer than 7,000 do. As the company imploded, its pension funds fell behind. During my stay I met former employees who had counted on a secure retirement and are now struggling to make ends meet. There were also plenty of salty epithets aimed at Perez, who is said to receive an annual salary of over $1 million, along with millions more in other compensation.

Some argue that Rochester as a whole is recovering. If so, it’s a slow climb.

Still, for cinephiles, Rochester remains a remarkable city. There is the historic Little Theater. It’s one of the oldest art houses in the country and now has several screens, all but one of them digital. The theatre has been taken over by the local NPR outlet and presents indie and foreign titles, along with some live music events. There’s also the magnificent Dryden Theatre operating under the auspices of the George Eastman House, one of the world’s great archives. Its programming has always been stellar, and it continues to bring rare films to the city.

Then there’s a real survivor: the Cinema Theater.

The South Wedge upstart

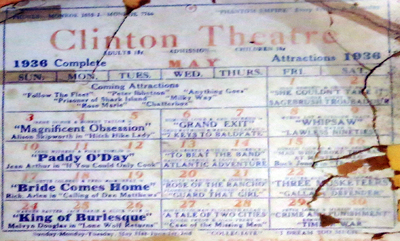

The Clinton Theatre, mid-1930s. The features are In Old Kentucky (1935) and The Return of Peter Grimm (1935).

It opened in 1914, smack in that period when motion pictures became the movies. It was initially called the Clinton Theatre because it occupies the corner of South Clinton Avenue and South Goodman Street. It offered minimal comforts. Donovan A. Shilling, in his colorful and nostalgic Rochester’s Movie Mania, tells of wooden benches and a dirt floor.

Those amenities couldn’t easily compete with the offerings of the Clinton’s more splendid rivals.

There was, for instance, the Piccadilly, opened in 1916. Advertised as a million-dollar house, the Piccadilly was built with a grand stairway and an orchestra pit for a sixteen-piece ensemble. Its auditorium could seat 1500 people in what the trade press announced as exceptionally comfortable seats. A beautiful exterior photo is here. Eventually the Piccadilly became the Paramount. Rochester was a pretty rich city then.

The Clinton closed in 1916, reopened briefly, closed again, and reopened in 1918. This time it held on. Located outside the central theatre district, in a neighborhood known as South Wedge or Swillburgh, the Clinton was a classic neighborhood second-run house. You might have to wait quite a while to see a release, which would play the downtown theatres first. But at least you benefited from a swift turnover. During one week of February 1929, you could see The Big Killing and Bachelor’s Paradise (on a double bill), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tim McCoy in Wyoming, The Crowd, and While the City Sleeps, starring Lon Chaney. These titles had been released in spring and early fall of the previous year.

The Clinton wasn’t part of a chain, but it hung on through Hollywood’s biggest studio years. In 1934 it was one of thirty-two Rochester theatres, some of them huge. The Century could hold 2500 people, the RKO Palace 3000. (Of course many such theatres hosted live shows as well.) With capacity of only 500 (about the same as the Little), the Clinton was in the same category as the Aster, the Broad, the Empress, the Hudson, the Lyric, the Majestic, and the Rexy. Admission was typically $.15, and that usually got you two pictures. Bills changed three times a week, with the big pictures running three days.

Surprisingly by our standards, the major films weren’t playing Friday and Saturday. I can’t prove this, but I’ve read that Sunday afternoons and evenings yielded the big audiences for neighborhood theatres–possibly because many people worked six-day weeks. (See the codicil for more information.)

But, as mentioned in an earlier entry, the late 1940s were problematic for exhibitors because attendance plummeted. In 1949, the Clinton was taken over by Jo-Mor Enterprises, a major Rochester chain. Renovated with the Art Deco façade it now has, the newly named Cinema played arthouse fare as well as subsequent-run Hollywood films.

The Cinema was headed for closure in the mid-1980s when it was saved by an unlikely heroine. Earth Science teacher JoAnn Morreale bought it and spent over $100,000 in improvements. She did everything from negotiating with distributors to cleaning toilets.

Her energy made the theatre what it had been in its heyday, a center for community activity. Locals came in with gifts and home-made treats. Some spent the day there, watching the double-feature matinee and the double-feature evening show. Six bucks got you four movies. Here’s the old beauty in 1992.

Two years ago the Cinema was bought by John Trickey. The house is still a second-run venue, but unlike most it still offers double bills. The night I visited with my sister Diane you could have seen Mandela and Gravity in one go. The prices have gone up only a little since the 1980s: $5 for adults, $3 for seniors, students, and kids under 12.

We met the Cinema’s majordomo Benjamin Tucker. By day Ben is a Curatorial Assistant at Eastman House, but he loves film history and is happy to help out the theatre.

The shows are still in 35mm, although Ben is coordinating a crowdfunding campaign to help out digital conversion.

Princesses

We met the staff, including the projectionists and the ticket lady Pat Russo, who has worked there for about ten years. She gives you real pasteboard tickets, not those flimsy, curly multiplex printouts.

And there’s the proud lineage of Cinema Theater cats, starting with Princess to Princess the second (ruling for about fifteen years) up to Sue, who’s been in residence about six months.

The Princesses would circulate among the seats, startling patrons by rubbing up against their legs or leaping onto their laps. Sue has a habit of settling down for a snooze in the middle of the line at the concession stand, forcing customers to step over her on their way to the popcorn.

I never visited the Cinema in my salad days (the 1960s). It wasn’t playing so much arthouse fare, I think, so I tended to visit the Little or the Dryden. I wish I had sought out the Cinema. This is one of the oldest continuously operating theatres in the country. Long may it flourish.

Thanks to Ben Tucker for information and images, to Jim Healy for tipping me off to the theatre, and to Diane and Darlene Bordwell for their company.

The image of the mid-1930s Clinton comes from Shilling’s Rochester’s Movie Mania; Carl Baxter supplied the original photo. More Clinton/Cinema Theatre memories here. The Rochester Subway site hosts stupendous, recently discovered photos of the RKO and Loew’s picture palaces.

PS 16 March 2014: Alert reader Andrea Comiskey supplies some background on the Clinton’s scheduling three programs per week during the classic years.

Mae Huettig (Economic Control of the Motion Picture Industry, 1944) says that only theaters that did not have to block-book (majors’ affiliates, members of large chains, etc.) got to choose films’ playdates. Whether this was really as absolute as she makes it sound, who knows? But what this means for when the “best films” (typically the A pictures) would tend to appear is tough to determine. On the one hand, you could imagine that distributors would want the strongest, most appealing films showing on the weekends when they could bring in the biggest crowds. On the other hand, you could imagine distributors trying to force underperforming/weaker films onto bills on the busier days since there’d be higher baseline business regardless of the merits of the films on the program. Exhibitors that didn’t get to pick playdates certainly did complain.

In an interview published in Kings of the B’s, (1975) Monogram’s Steve Broidy says that Saturday is the busiest day, at least for small-town exhibs. He also says that these exhibs liked flat-rate rentals on Saturdays so they could run up the profits and echoes the idea that the particular film didn’t matter a ton since people were going out to the movies regardless.

As was the case with your Rochester example, theaters that changed programs 2 or more times a week (which, at least in big cities, were more likely to be sub-run houses) often split the weekend days across two programs, with many theaters adding an extra feature exclusively for the Saturday kiddie matinee. I’ve seen just about every possible permutation, but for a twice-weekly changeover, Sun-Wed & Thurs-Sat was a pretty common pattern. For thrice-weekly, Sun-Tues, Wed-Thurs, & Fri-Sat was common. But I’ve also got plenty of examples of theaters that showed the same program Sat. & Sun.

Andrea is writing a dissertation about distribution and playdate patterns in the 1930s. I’m happy to get her clarification here, which shows, as usual, that film history is always more complicated than it seems at first.

The Cinema, 2014. Photograph by Darlene Bordwell.

The book stops here: Theory, practice, and in between

Tinpis Run (Pengau Nengo, 1991).

DB here:

Apart from things I’m reading for research (academic monographs, 1940s Hollywood novels, star bios and autobios), the film books I like best are blends. They bring together information, ideas, and opinion. I learn some facts about films and their contexts. I encounter some concepts that illuminate those facts. And I get introduced to some arguments about the best way to understand the information and ideas. In my ideal world, the blend winds up answering some questions—maybe questions I’ve thought about, maybe ones that never occurred to me.

I especially like books that have one foot, or toe, in filmmaking practice. The poetics of cinema I try to practice is, from one angle, an effort to grasp the principles underlying filmmakers’ creative choices. Sometimes those choices are announced by the filmmakers; sometimes we have to reconstruct them on the basis of the films and other data. So for me a drastic split between theory and practice isn’t very informative.

These pronunciamientos are but prelude some comments on books that push several of my buttons. Maybe they’ll do the same for you.

Philosophy goes to the multiplex

Stagecoach (1939); True Grit (1969).

What book brings together Cézanne and Tony Soprano, Gregory Peck and Simone de Beauvoir, Plato and South Park, The Twilight Zone and Wittgenstein?

Okay, I know the answer: Practically every book by a littérateur convinced that Great Big Theory gives you a way of talking authoritatively about anything, especially pop culture. So I rephrase my question: What book brings together these and many more items with care, rigor, and infectious amusement?

That narrows the field quite a bit. A strong candidate is a book that has chapters like “What Mr. Creosote Knows about Laughter,” “Andy Kaufman and the Philosophy of Interpretation,” and “The Fear of Fear Itself: The Philosophy of Halloween”— not the movie but the holiday itself.

The short answer to my question: Noël Carroll’s new collection of essays, Minerva’s Night Out: Philosophy, Pop Culture, and Moving Pictures.

Noël Carroll isn’t merely the most important philosopher ever to write about popular culture. He has been for decades a major force in film theory and criticism, as well as a philosopher making contributions to moral and legal theory, historiography, and a welter of other areas. His fertile mind and prodigious typing skills have combined to produce over fifteen books and a list of articles running to triple digits.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

It’s not just quantity, of course. For those of us in media studies, Carroll has been the most well-informed and adroit analyst of trends in film theory. His Philosophical Problems of Classical Film Theory (1988), Mystifying Movies: Fads and Fallacies in Contemporary Film Theory (1988), and Post-Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies (1996, coedited with me) have proven enduring contributions to the debates about the best ways to understand the nature and functions of cinema. He is, as you can tell, a controversialist. Like all good philosophers, he’s devoted his life to getting the ideas right. Over the same period, Carroll has proven himself a wide-ranging practical critic, discussing classic silent films (especially comedy), modern avant-garde work, and Hollywood movies from the 1930s to the most recent releases. This isn’t to slight his important work as a dance and television critic as well.

This focus on film theory stems from the fact that Noël’s first Ph.D. degree was in film studies. But soon afterward he went on to get a second Ph.D. in the philosophy of art. His cinema research was always philosophically informed, but once he became a card-carrying philosopher, he commuted between two academic areas. He helped found the broader movement called Philosophy of Film, and he continues to write on a lot of different topics. His Humour: A Very Short Introduction is due out in a couple of weeks.

Minerva’s Night Out scans the range of his interests—not only all types of media (which he genuinely enjoys) but a variety of the philosophical puzzles they pose. These he tackles with verve, patient but not plodding analysis, and a range of references that make you wonder if this guy has seen and read pretty much everything.

Here’s the sort of thing that Noël thinks about. We all know that to enjoy a movie fully we often have to appreciate the way in which a star’s performance builds on previous roles. But there’s a problem. The fictional world of a film makes only certain types of knowledge relevant to our experience. At the center of this knowledge is what Carroll calls the “realistic heuristic,” the premise that all other things being equal, the things happening in the fiction are assumed to operate under the laws of our everyday world. Sherlock Holmes (whether incarnated by Basil Rathbone or Benedict Cumberbatch) is presumed to have lungs like the rest of us, unless we’re told otherwise. Likewise, it is true in the fiction that a room’s walls are solid, while they might in reality be fake. If I see the walls as painted sets or green-screen mattes, then I’m not responding to them as part of the story world.

The same attitude shapes our sense of the unfolding plot. Armed with the realistic heuristic, we have to assume that characters’ destinies are open, that many things can happen to them (as with us). But the principles by which a movie fiction is constructed—say, boy gets girl—aren’t part of our realistic heuristic. “What we believe is probable of a movie qua movie is radically different from what we believe to be probable in a movie conceived as a credible fictional world.” Movie lore tells us that boy will get girl, but to grasp and respond to the story emotionally, we have to feel in doubt. (Perhaps this is what people mean when they say that a mistake in the movie, or a distraction in the auditorium, takes them “out of the movie.” We’ve left the fiction.)

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Similarly, movie lore connects the Ringo Kid of Stagecoach to Rooster Cogburn of True Grit (the original) because John Wayne portrays both. Yet the characters live in different, sealed-off story worlds. Ringo and Rooster have no knowledge of each other. Barring transmigration of souls, how can their connection be part of our experience of either movie as a consistent fiction?

Carroll comes up with an ingenious explanation. Movies summon up star personas in the manner of allusions. Just as our experience is enhanced when we see a movie refer to another movie—Carroll’s example is a citation of Rocky in In Her Shoes—so do our mind and emotions respond to the presence of the star, as either a continuing allusion throughout the film or a one-off one, as with a cameo or walk-on. As he often does, Noël points out that practicing filmmakers use the concepts he elucidates. “Allusive casting” became part of the 1970s trend of paying homage to old Hollywood, but even in the studio era it wasn’t unknown. Carroll points to The Bigamist (above left), in which somebody says another character looks like Edmund Gwenn. Of course said character is played by Edmund Gwenn.

I’ve shrunk down Carroll’s line of reasoning to give you the flavor of the way he thinks. His piecemeal approach to theory focuses not on loosely named topics but specific questions. For example:

What if anything justifies us talking about popular culture as all one thing?

How do fiction films engage us in the emotional lives of their characters? Hint: It’s not through identification.

What makes us laugh at Mr. Creosote, rather than be horrified or disgusted by his vomit-laced gluttony?

How does a tale of dread, such as Poe’s “The Black Cat,” differ from a horror story?

Why should we care about Tony Soprano, who barehanded commits “crimes of which I don’t even know the names”?

Are the feelings awakened by art akin to friendship?

What role do moral emotions, such as the sense of community, play in our response to characters?

As for the jokes, they’re not of the esoteric academic type but rather straight-out funny. Just one essay, on the vague/implausible (you pick) notion that modernity (traffic, window displays, lotsa flashing lights) changed the very faculty of human perception:

The human eye rarely fixates; saccadic eye movement is the norm. We did not suddenly become attention-switching flâneurs in the late nineteenth century; we have been natural-born flâneurs since way back when.

No amount ot cultural conditioning will succeed in making normal viewers worldwide literally see human faces as cross-sections of centipedes.

I’m sure he’d give any indie filmmaker the rights to make Natural Born Flâneurs.

Viewers and their habits

Natsukawa Shizue in Town of Hope (Ai no machi, 1928).

Carroll tries to figure out certain logical conditions on spectators’ experience in general. That’s one province of film theory. But he’s also sensitive to the constraints on those conditions, the ways that historical and institutional circumstances can shape how viewers watch movies. (That’s part of the star-as-allusion argument.) Other researchers, historians by trade but sensitive to theoretical implications, have tried reconstructing the activities of theatres, trade personnel, and audiences in particular times and places.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A good cross-section of approaches has just appeared from Karina Aveyard and Albert Moran. Their anthology Watching Films: New Perspectives on Movie-Going, Exhibition and Reception contains 22 chapters of empirical research spread across the Europe, New Zealand, Australia, and the U.S. The researchers take us to particular cities and towns (Antwerp, Nottingham, and the Scottish Highlands) and to various points in history, from the 1920s to the present, passing en route the arrival of TV and the effects of the VHS revolution. There are also considerations of early reception theorists like Barbara Deming, along with studies of fan activities in Italy and elsewhere. Altogether, you couldn’t ask for a more enticing sampler of contemporary strategies for studying how audiences interact with cinema. Multiplicity long preceded the multiplex.

A similar approach, but focused with razor acuity on a single country and period, is Hideaki Fujiki’s Making Personas: Transnational Film Stardom in Modern Japan. This book is an expedition into a nearly sunken continent, Japanese film of the silent era. Frustratingly few films have been preserved from those years, but paper documents abound. Fujiki has made intense use of them to answer the question: What were the cultural causes and results of the early star system in Japan?

The answers are rich and detailed. The very first stars weren’t on the screen at all; they were the benshi who narrated the silent program. Hideaki goes on to trace the career of the paradigmatic male star, Onoe Matsunosuke, and to show how his main traits (virtuosity and stature as “great man”) were reinforced by a troupe-based business model. Later chapters focus more on female stars, with emphasis on the influence of American actresses like Clara Bow. The flapper figure shaped not only Japanese female performers but women in real life.

Fujiki traces in some detail how the “modern girl” or moga floating through Ginza owed a good deal to Hollywood movies. He makes good use of what films survive from this period, particularly The Cuckoo (Hototogisu, 1922) and Town of Love (Ai no machi, 1928). In-depth analysis of the star image Natsukawa Shizue, above, allows him to discuss fan culture and movies’ role in accelerating trends in fashion and advertising. In all, Making Personas is a fascinating consideration of stardom as both an industrial and social construction in one of the world’s most important national traditions.

Education and environment

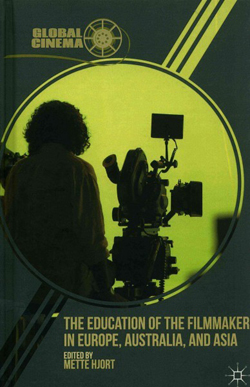

Institutions of another sort feature in two impressive books from the prolific Mette Hjort. She has had the very good idea of assembling documentation about how film schools work. How do different schools, academies, and more informal agencies understand the craft of filmmaking? What ethical values and social commitments are brought to the classroom and enacted in the production process? What are the histories of film schools around the world?

The answers come in two packed anthologies, The Education of the Filmmaker in Africa, The Middle East, and the Americas, and The Education of the Filmmaker in Europe, Australia, and Asia. From these we learn of the creative practices put into action by institutions in Nigeria, Palestine, Denmark, the West Indies, China, Hong Kong, Vietnam, Sweden, Germany, Australia, Japan, and many other localities. We get a real sense of intercultural communication and its breakdowns. Rod Stoneman points out that Tinpis Run, Papua New Guinea’s first indigenous feature, demanded postproduction discussions when outsider viewers couldn’t distinguish the villages presented in the story.

Things happen in these places that would astonish students at UCLA and NYU. Hamid Naficy tells of taking his Qatar students to Tanzania, where they worked on research projects only after spending the morning doing clerical and custodial work in schools and hospitals. We learn of children’s filmmaking initiatives in Mexico City, programs for at-risk youths in Brazil’s City of God favela, and students making photo and sound montages in Calcutta. One purpose of Mette’s collections is to remind us that film training goes far beyond getting your MFA and a showreel on a maxed-out credit card.

Hjort’s initiative, while already stimulating, ought to be continued and enriched. People are starting to understand the importance of film festivals within film culture—as distribution mechanisms, publicity arms, and in a roundabout way feedback systems shaping production. (One essay, by Marijke de Valck, points out the move by festivals toward film training.) More generally, we need to understand film education at all levels as shaping film production and film audiences.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Hjort’s introduction emphasizes that institutional politics are always related to larger political and cultural concerns. Social implications of filmmaking are brought to the fore in another emerging area of research. As each day seems to signal a new ecological disaster, it’s timely that a critical school has emerged to track how films and TV represent our relation to nature and technology. Among the scholars working prolifically in this area are Robin L. Murray and Joseph K. Heumann.

Their first book, Ecology and Popular Film: Cinema on the Edge argues that apart from films like An Inconvenient Truth, which wear their green politics on their sleeve, there’s a much bigger and broader tradition of films about humans and the environment, ranging from fictional films with explicit messages, like Happy Feet (2006), to films with unintentional ones, like The Fast and the Furious (2001).

As “second-wave” practitioners of eco-criticism, Murray and Heumann aren’t much concerned with cheerleading or finding villains. They want to explore how media representations of the environment have responded to various cultural pressures. Their two most recent books are good examples. That’s All Folks? (2009), building on their analysis of Lumber Jerks in their first book, concentrates on American animated features. They perform careful symptomatic readings while also providing industrial context, such as the tactics by which Lucas and Spielberg adapted to the growing dinosaur craze of the 1990s.

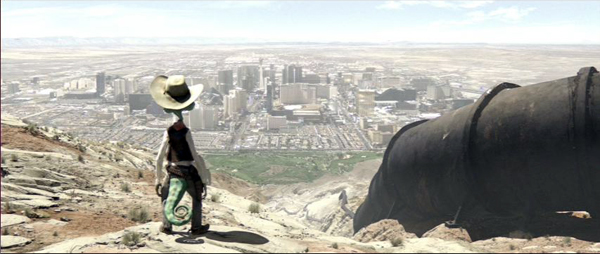

In Gunfight at the Eco-Corral (2012), Murray and Heumann tackle the Westerm on similar grounds, ranging from Shane and Sea of Grass to There Will Be Blood and Rango. Reading these chapters I was reminded how often the genre’s plots hinge on disputes over natural resources. Water, minerals, timber, grazing land, and what the authors call “transcontinental technologies” like the telegraph and the railroad are at the heart of classic Westerns, and the genre’s formulaic conflicts often have strong ecological resonance. This is the sort of criticism that refreshes your vision of movies you think know very well.

Their next book, Film and Everyday Eco-disasters is due out in June.

Things stick together

Lone Survivor (2013).

Finally, two more books merging theory and practice—but from opposite ends of the spectrum. One question that intrigues me involves coherence and cohesion in film. Roughly speaking, coherence involves the way the whole movie hangs together. If it’s a narrative film, how do the scenes or sequences fit into the larger plot? If it’s not narrative, what other principles organize the whole shebang? Cohesion involves how adjacent parts fit together—shot against shot, sequence to sequence. Both these concepts have practical implications, since every filmmaker confronts concrete choices about them in scripting, shooting, and editing.

Michael Wiese has contributed enormously to our understanding of filmmaking practice by publishing a series of books on cinema craft. The most recent one I know is by Jeffrey Michael Bays and it bears directly on cohesion. It’s called Between the Scenes: What Every Film Director, Writer, and Editor Should Know about Scene Transitions. Bays himself has written and directed films, written radio dramas (a great place to study transitions), and published books on filmmaking.

Between the Scenes is an entertaining and damn near exhaustive account of the ways that images and sounds can tie one scene to another. Bays considers aspects of space, like location or objects or actors; time; and visual graphics. The book also shows how sounds can bind scenes or emphasize sharp contrasts. In the example from Lone Survivor above, a soft whir of helicopter blades is heard over the first shot and grows louder when we move from the map to the landing area.

In a web essay called “The Hook” I explored some aspects of this process, but Bays goes into much more detail with many recent examples. He also raises ideas I never considered. For example, if we think of narratives as people traveling from one place to another (and most narratives are that, at least), then every filmmaker faces a choice: Show the journey or don’t show it. And if you show it, what parts and why and what does it tell us about the character? The larger point is: “Make sure you know where every character goes between every scene.” Thinking about this suggests ways to enrich your presentation, and it allows the characters—if only in your imagination—to inhabit a more fleshed-out world. Ideas like this can provoke everyone, filmmakers and film scholars alike.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

Small-scale links between parts are considered more theoretically in Chiao-I Tseng’s Cohesion in Film: Tracking Film Elements. Trained in functionalist linguistics, Tseng brought her expertise to bear on film analysis. The results show a remarkable kinship between devices in language and certain cinematic transitions. Such linguistic functions as saliency (what stands out) and presumption (what can be taken for granted) are found in audiovisual texts too. For example, a shot taken over one character’s shoulder tends to lessen that character’s saliency and make another character, the one we see more clearly, more prominent.

This example is simple, but once Chiao-I gets going, she’s able to show how nearly every cut or camera movement can be seen as activating a unique tissue of cohesion devices. The words in a paragraph not only refer to ideas or things; they also link to other words in the paragraph and in the larger discourse. Similarly, in film, different aspects of the images and sounds stand out and adhere to one another instant by instant. Tseng’s analyses of passages in Memento, The Birds, The Third Man, and other films are accompanied by equally close studies of television commercials and educational documentaries. At the end, analysis is supplanted by synthesis, as she shows how the configurations she has pulled apart coalesce into levels that highlight characters and actions. It’s a fresh way to think about how we understand films within genres and stylistic traditions.

In effect, she’s showing the fine-grained patterns that emerge from the choices every filmmaker faces. It would be fascinating to sit in on a dialogue between Bays and Tseng, for they belong to the same community, or so I think anyhow. We’re all trying to understand aspects of cinema, and by focusing on certain phenomena rather closely, we have a good chance to understand them better.

So to the filmmaker who’s skeptical of theory, I say: We can’t think clearly without concepts, or talk clearly without terms. We need to develop rigorous ideas and arguments (i.e., theory) to understand film as best we can. But to the would-be theorist I say: Keep fastened on the look and feel of the films, and test your ideas and arguments not only against them, but against what you can find out about the craft of cinema, in all its historical implications.

I was pleasantly surprised, after I’d decided to talk about these books, to find work by Kristin and myself cited in some of them. Remaining coldly objective, however, I didn’t let these mentions diminish my praise.

Rango (Gore Verbinski, 2011).

Nothing, if not critical

The Woman in the Window (1944).

O, gentle lady, do not put me to’t,/ For I am nothing, if not critical.

Iago, Othello

DB here:

Movie aficionados seem endlessly interested in film criticism—not just in what a writer says about a film, but in the very idea of criticism. I’ve suggested in a recent entry some of the historical reasons for this: the rise of the celebrity reviewer in the 1960s, the surge in interest in foreign and alternative cinemas, the emergence of filmic experiments, from Persona to Memento, that seemed to demand discussion.

With the internet, you can’t turn around without bumping into a film review. Aggregate sites like Rotten Tomatoes and Metacritic get tens of millions of hits a month. Of course many people are just checking on the range of opinions of a specific release, but I get a sense that many readers are more or less addicted to critical buzz as such. Connoisseurs of sentiment and snark, they still follow favorite reviewers just as we did in the 1960s, and they enjoy reading a critic they don’t agree with because she or he is an enticing writer.

In one corner of my workroom a steadily growing pile of books is no less a tribute to the flourishing of film criticism. Yes, books. I’m a committed Netizen (I’d better be, after three e-books, several web essays and videos, and over 610 blog entries). And for certain purposes, such as word search, I prefer digital versions of texts. But nothing beats a book for reading anywhere you happen to be, thumbing back to check a point, marking up margins with invective, and throwing across a room when you’ve decided the author is a dunce.

Here, though, are some books that won’t become missiles.

Revaluation

One consequence of the 1960s cult of the movie critic was a new genre of book—the anthology of a writer’s reviews, think pieces, and long-form essays, perhaps spiced by an interview or two. Call it a predecessor of a website if you must, but such books were tempting packages to cinephiles who wanted their fix in big gulps, not weekly doses. Then we eagerly read through Agee on Film, Dwight Macdonald on Movies, Kael’s I Lost It at the Movies, and many other collections. Some of these are now classics, most are forgotten, but the format still has life in it. Roger Ebert, exceptional in all respects, kept it going for years and crowned it with his Great Movies series. The format passed to academic presses like Wesleyan with Kent Jones’ Physical Evidence (2007) and Chicago with Dave Kehr’s When Movies Mattered (2011).

Like me, James Naremore is a creature of the 1960s, but with his typical discretion he has waited forty years to bring together a collection. Jim’s 1973 Filmguide to Psycho introduced me to his elegant thinking about movies. Since then he has written about a great many subjects, always with wit, steady vision, and deep and unostentatious learning. Now we have An Invention without a Future: Essays on Cinema (University of California Press).

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

Every essay here is a polished gift from a master of the literary essay. The book’s first section considers classic topics like adaptation, authorship, and acting. It includes a sharp discussion of the rhetorical dimension of both filmic creation and critical commentary. In the second section we see Naremore the close reader, turning to the classic Hollywood cinema he has done so much to illuminate. He considers Hawks, Hitchcock, Welles, Huston, Minnelli, and Kubrick—the subjects of earlier writing he’s done, but now refocused through new lenses. One recurring question is: Does cinema, either as a physical medium or a public spectacle or a humanistic art have a future? Although the book’s compass swings constantly to the 1940s through the 1960s, Jim is fully up to date, writing with sensitivity on Shirin, Uncle Boonmee, and Mysteries of Lisbon.

The latter pieces were among Jim’s efforts at real-time film reviewing at Film Quarterly. Perhaps the sharpest edge of the book comes in the section housing them, called “In Defense of Criticism.” Jim, I think, considers criticism as, say, Lionel Trilling or Edmund Wilson considered it. Endowed with a tolerant, generous mind, the critic uses all the resources of culture—philosophical and moral ideas, social forces, artistic traditions—to illuminate the unique identity of the artwork.

More deeply, the critic expects the encounter with the artwork to challenge and change us. This to me is one difference between the reviewer and the critic. The reviewer expects the film to live up to his or her solidly entrenched point of view. The critic is open to being shaken, taught, and even transformed by the film. The reviewer projects confidence, the critic displays curiosity.

This ambitious conception of criticism is at risk today from two forces. There is the sheer blather of pop journalism and the Internet, which have pushed film culture from criticism to comments to chat to chatter. At the other end, some professors are allied against film as an art.

Today the humanities are in danger of losing their soul. Academic film studies has tended to focus on formal systems, industrial history, fandom, and identity politics—essential topics without which good criticism can’t be written, but topics that don’t engage directly with questions of art and artists.

Admitting that a certain detachment is valuable for research purposes, Naremore thinks that academics have become somewhat too clinical. Part of his book’s purpose is to draw their attention back to the intellectuals who flourished outside the academy, and for whom quality was worth arguing about.

I nevertheless think that evaluative criticism needs to be encouraged more, and I miss the days before the full-scale development of film studies, when film was made exciting and relevant by virtue of critical writing and debates over value.

So the last section consists of thoughtful essays on James Agee, Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, and Jonathan Rosenbaum—those who “had the greatest influence on the development of my taste.”

For my $.02, I’d just add that appraisals of quality shape a lot of academic writing, even in the Cult Studs vein. Showing that a film is racist or classist is surely an exercise in evaluation, employing moral or political criteria. Showing that fans of Twilight aren’t dumb no-hopers often springs from the researcher’s own esteem for the franchise. (Remember one of The Blog’s mottos: We are all nerds now.)

In effect, I think, Jim is pointing out that in a lot of film studies evaluation isn’t framed in specifically artistic terms. On that I’d certainly agree. Jim opens a new conversation by asking academics to look beyond their specializations and learn how the best arts journalists argue about quality. Seriously thought-through yet accessible to all, An Invention without a Future is a bracing, quietly subversive book.

Auteurs: From the ridiculous to the sublime

Jim would find signs of hope in two books dedicated to major directors.

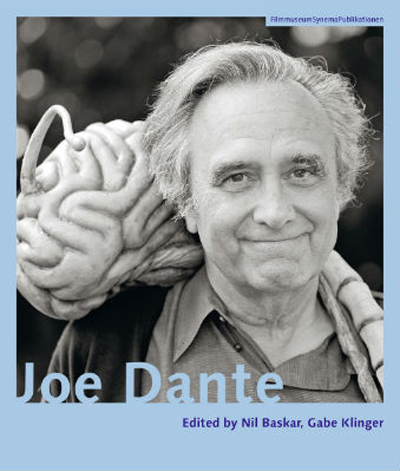

Nil Baskar and Gabe Klinger’s Joe Dante, a collection from the enterprising SYNEMA series at the Austrian Film Museum. Dante is just the sort of auteur that cinephiles prize. Working on the fringes of the system in despised genres, he’s a Movie Brat who loves B cinema, noir, and crazy comedy. This thick, square book contains virtually everything you’d ever want to know about the man who could be seen as Spielberg’s demented, funnier alter ego. Dante’s kiddie adventure stories and teen terror pix have celebrated and parodied Americans’ feverish love of war, big business, junk food, and lunatic media.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

From The Movie Orgy through Looney Tunes: Back in Action to The Hole (still not released in 3D in the US, as far as I know), Dante has been a paradigmatic case of the termite artist praised by Manny Farber. In this collection John Sayles recalls that for The Howling he and Dante agreed they would center on characters who knew horror-movie conventions and wouldn’t make the typical fatal mistakes. Bill Krohn, J. Hoberman, Christoph Huber, and Michael Almereyda are among the admirers assembled here, and their spirit of amiable, film-geek homage is infectious. There’s also a long interview with Klinger, a detailed chronology, and a filmography zestfully annotated by Howard Prouty.

Dante’s opposite number is Béla Tarr, whose films run the gamut from glum to morose, but they’re no less exhilarating. They find their ideal explication in András Bálint Kovács’ The Cinema of Béla Tarr: The Circle Closes. Kovács scrutinizes all the films, some little-known outside Hungary, and produces careful analyses that balance thematic interpretation with precise examinations of style. As a friend of Tarr’s, András is in a unique position to take us into this filmmaker’s grimy, splendid world.

Tarr, Kovács suggests, asks his audience to accept the illusions shaping the narrative world. Yet his structure and technique in the end yield a clearer view of the underlying forces than the characters can achieve—often, forces driven by conspiracy or betrayal. Accordingly, Tarr’s narratives tend to be cyclical, even when the story situation is unchanging, and his camera movements often trace a circular path. Many readers will particularly welcome Andras’ exciting account of Sátántangó, Tarr’s most demanding film. Based on a novel with an intricately circular structure, the film finds its own means to suggest a story swallowing its own tail. Most film books nowadays have pretty good frame illustrations, but these are well-sized to illustrate some of Tarr’s fine points of staging. In all, this book is likely the definitive study of Tarr’s art.

Museum pieces

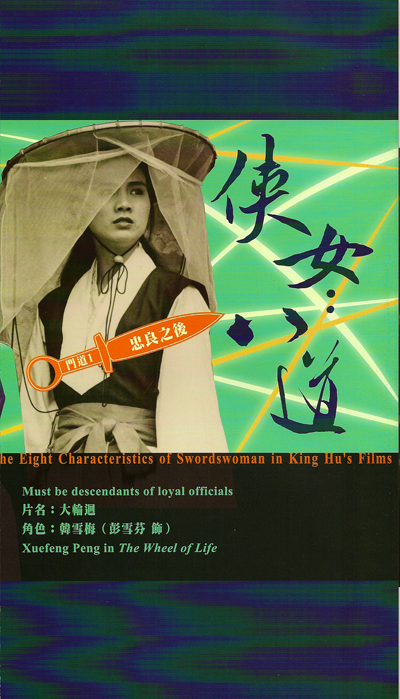

There’s another way to make the case for an auteur’s value: produce a dazzling book that pays tribute with gorgeous illustrations and informed critical commentary. This has been done by Taipei’s Museum of Contemporary Art in its catalogue King Hu: The Renaissance Man.

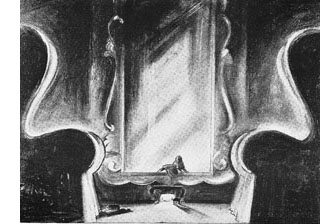

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

The 2012 exhibition it preserves in its pages went beyond the usual regimen of talks and panel discussions. There were children’s events and in-person painting of film billboards. In one display, you could watch Tsui Hark’s calligraphy form a tribute to his master (“The integrity of swordsmanship remains as the spirited rain….”). An installation tableau by Tim Yip presents a modern woman watching King Hu TV appearances while texting, her vacant mind suspended between two spaces.

Open the catalogue and you’re greeted by a large gatefold that sums up King Hu’s career. Thereafter, articles like Edmond Wong’s study of King Hu’s archetypes (derived from legend and theatre) supply the academic ballast, while images of the gallery displays fill up page after page. There are photo essays devoted to each of the films, as well as more gatefolds, illustrating themes such as “The Eight Characteristics of Inns in King Hu’s Films.” Just the hundred pages of King Hu documents—stills, portraits and self-portraits, along with caricatures of Bill Clinton and Princess Di—would be worth our attention. In all, this is the sort of museum show every cinephile dreams of visiting.

Art historian Steven Jacobs, author of The Wrong House, has collaborated with Lisa Colpaert to produce a dream of another sort. Their book invites you into an imaginary exhibition.

Visualize a museum containing all the paintings you find in films of the 1940s and 1950s. Now assume that some diligent scholar has sniffed out the provenance of all of them and provided stylistic and thematic commentary. And now assume that the research is presented as a guide to this virtual museum, using all the paraphernalia of art-historical commentary.

Confused? Here’s the opening of one entry:

[III.9] Portrait of Lady Caroline de Winter

(Unknown Artist, late 18th Century)

This full-length portrait represents Lady Caroline de Winter (1760-1808). The carefully rendered white dress, the column and curtains, and the vista of the landscape are unmistakably reminiscent of the portraits by Thomas Gainsborough, for instance his often-reproduced The Honourable Mrs. Graham (1775-1777). The landscape with trees probably stands for Manderley, the de Winter family estate on the Cornwall coast. For more than a century, the portrait was hanging in a long corridor in Manderley’s east wing, which was decorated with ancestral de Winter portraits. In the 1930s, the portrait played an important part in the life of one of Lady Caroline’s descendants, Maxim de Winter (Laurence Olivier). Maxim’s first wife Rebecca died in mysterious circumstances and once had a copy made of the white dress on the occasion of a masquerade ball at Manderley. . . .

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

This straight-faced experiment in creative criticism is called The Dark Galleries: A Museum Guide to Painted Portraits in Film Noir, Gothic Melodramas, and Ghost Stories of the 1940s and 1950s. All the conventions are there: the scene-setting introduction, the iconographic interpretations (“crimes and clues,” “paintings concealing safes”), and an exhibition guide that takes you from room to room, from Dying Portraits to Ghosts to Modern Portraits and more. They track the ways in which paintings in movies have altered time, refashioned faces, and, if the painting is disturbingly “modern,” signified madness and criminality. As zealous researchers, Steven and Lisa have done what they could to trace the provenance of the actual artifacts too, and they’ve discovered a large number of commercial artists hired by the studios.

A few years back at our summer film school, Steven impressed me when he identified the famously puzzling cubist still life in Suspicion as Picasso’s Pitcher and Bowl of Fruit (1931). The ultimate result of his and Lisa’s efforts is at once charming and deeply serious, enlightening us about a major motif in Hollywood’s “dark cinema.” It’s an extraordinary accomplishment, and an ideal gift for the patriarch, matriarch, exotic woman, or mystery man in your life.

Thanks to Lin Wenchi for giving me the King Hu catalogue. I’m unable to find an online source for this book, but when I do I will note it here. In the meantime, the sponsoring museum produced several videos for the exhibition. YouTube supplies a playlist of them. Our entries on this great director are here. I discuss his work in more detail in the books Planet Hong Kong and Poetics of Cinema.

For more exercises in creative criticism, visit Hilde D’haeyere’s website on silent comedy.

For more thoughts on film criticism on this blog, go here and here and here. A series on major American film critics of the 1940s starts here.

I record Joe Dante’s visit to Madison here and wrote about Béla Tarr’s films in these entries.

F for Fake (1972).

Screenplaying

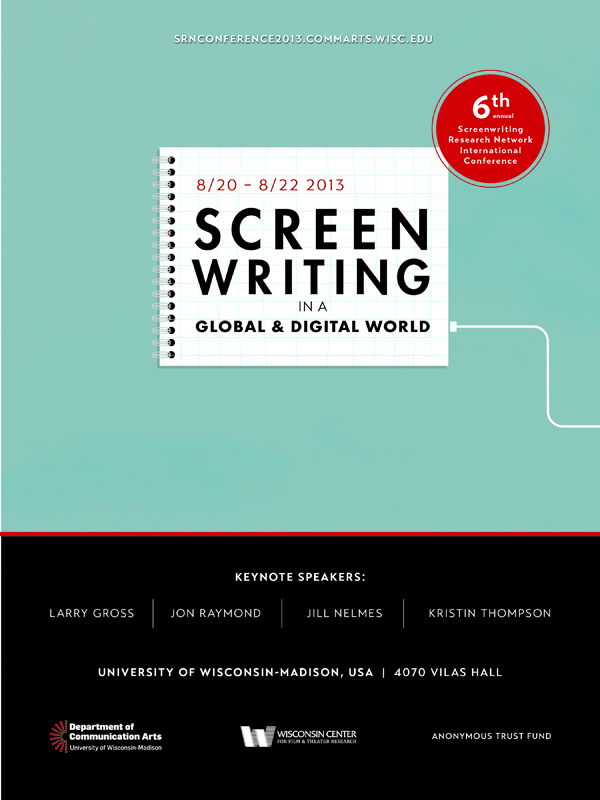

Design by Christina King.

DB and Kristin here:

Two years ago DB reported on the gathering in Brussels of the Screenwriting Research Network (here and here). This year, thanks to our colleagues J. J. Murphy and Kelley Conway, our department hosted the conference. Again, it was chock-a-block with stimulating papers. We also introduced our visitors to the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which houses thousands of screenplays. It wasn’t all work, either. Participants were spotted lingering at our lakeside terrace or making their way through the cafes and saloons lining State Street. We believe it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all.

Since there were simultaneous sessions, nobody could attend everything, and we can’t run through all the papers we heard. (So do consult the program for more information.) Herewith, some highlights that set us thinking.

In the key of keynote

Larry Gross and Jon Raymond.

The four keynoters encapsulated the conference’s very wide range. In a workshop keynote Jill Nelmes, Editor of the Journal of Screenwriting, offered a historical survey of screenwriting research in all media, with special emphasis on television. The Big Hollywood Movie was covered by Kristin, whose paper, “Extended How?” examined the ways in which directors’ cuts and extended editions handle the multi-part structure she posits as a foundation of contemporary Hollywood. We won’t say more here, since she may turn it into a blog for this site.

Larry Gross had already started off the conference with a bang by taking us to Japan. Larry has written 48 HRS, Streets of Fire, Geronimo, True Crime, and other mainstream studio pictures, as well as television episodes, TV mini-series, and independent films like Prozac Nation and We Don’t Live Here Anymore. He also writes outstanding film criticism for Sight and Sound, Film Comment, and other journals, and he teaches screenwriting at New York University. Scott Macauley’s informative March interview with Larry is at Filmmaker Magazine.

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

Larry’s keynote, “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting,” tackled the question of how filmmakers decide to share story information with the audience. What do the characters know and when do they know it? What does the audience know, and when? Storytelling, Larry suggested, develops out of the interplay of these two sets of questions. He added, perhaps hoping to provoke purists who consider film to be sheer self-expression: “Thinking about the audience is not always reactionary.”

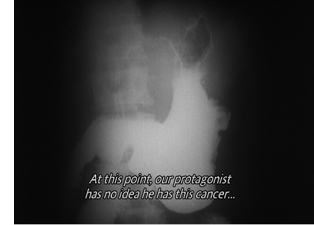

He illustrated his ideas with an in-depth examination of Kurosawa’s Ikiru. He had long thought the film “an official liberal-humanist classic,” until a course with Annette Michelson at NYU showed him that there was a lot to ponder there. Specifically, Kurosawa starts by telling the audience the end of the story: Watanabe will die of cancer. But he doesn’t know that, and neither do all the people he encounters. The strategy denies us a lot of suspense, so to hold our interest Kurosawa must engross us by delineating his relations with his colleagues, with the mothers petitioning for the neighborhood sump to be drained, and with the stray people he meets casually on his night out.

Larry showed how carefully Kurosawa played off the characters’ indifference, misunderstanding, and lack of awareness. In particular, the neighborhood wives display to Watanabe what Maurice Blanchot called “the ignorance and spontaneity of true affection.” Ikiru’s refusal to explain what it means typifies a kind of cinema that asks the audience to share the burden of understanding. “Ikiru understands how a screenplay can be composed with the audience.”

Jon Raymond’s keynote carried things to independent US film. Jon has become famous for a novel (The Half-Life) and short stories (Livability), as well as for his screenplays for Kelly Reichardt’s features. The most recent, the forthcoming Night Moves, is currently in competition at Venice. The teaser title of Jon’s address, “Screenwriting as Earth Art,” turned out to be a reference to the fact that most of his stories take place in the vicinity of his home. He has found satisfaction by composing on familiar ground.

In younger days Jon tried painting and filmmaking; a Public Access feature based on the comic strip Crock turned out to be “a movie best experienced in fast forward.” But he found that writing offered the most creative satisfaction. At the same time, while assisting Todd Haynes on Far from Heaven, he met Kelly Reichardt, who was looking for a property to adapt on a small budget. The result was Old Joy, “a New Age western,” in which two men display the violence latent in the new passive-aggressive masculinity flourishing on the Coast. Jon believes that Reichardt’s handling created a cinematic parallel to the dense intricacy of a short story.

In later collaborations, Jon mapped his patch of Portland in other ways. Seeing the annual migration of workers to Alaskan canneries, and hearing the train whistles wafting through his neighborhood, he created the story that became Reichardt’s Wendy and Lucy (above). Reichardt began adapting the story to film before he had finished writing it. Similarly, Jon merged the booming housing market of the 2000s and the history of the Oregon Trail into a project that paralleled today’s gentrification with nineteenth-century colonization. Reichardt turned his screenplay into Meek’s Cutoff, a “desert poem” that completed what some have called their Oregon Trilogy. For Jon, the trilogy constitutes an alternative regional history, one that traces the process of “sowing the land with failure, betrayal, and humiliation.”

Plots and no plots

The Adventures of André and Wally B (1984).

More than most areas of filmmaking, screenwriting reminds us of the institutional framework surrounding most creative work cinema. Scholars studying the screenplay are naturally often pursuing the endless revisions, refusals, and rethinks that a film goes through in the preparation phase. It’s easy to see this as a one-versus-one struggle, but in many cases the process takes place within a social environment possessing its own roles and rules.

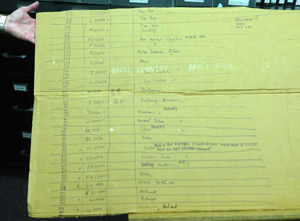

Ian MacDonald offered an excellent example in his study of the work processes behind the UK television soap opera Emmerdale. He proposed that we replace model of industrial film production as an auto factory with that of a carpet factory. Instead of the TV episode being seen as a discrete unit, like a car, it should be conceived as an ongoing fabric woven of many threads. In Emmerdale and other series, the unit of production isn’t the episode but rather the story line. Each episode is sliced out of a much bigger stretch of ongoing patterns. Ian illustrated this with the writers’ planning chart that was mounted on the wall.

The vertical column represents scenes, marked off as episodes. The characters are color-coded cards connected by solid liness that weave their way through the scenes. These waves are the melodies; the scenes are the bar-lines. In each episode, two or three characters are given prominence, while the subordinate ones contribute their harmonies. Ian’s discussion reminded me of how Hong Kong filmmakers did much the same thing in the 1980s: plotting films reel by reel and color-coding certain elements—gags, fights, and chases—to make sure that each reel had its share of attractions. This is the sort of insight into structure that institutional research can yield: Structure is these people’s business.

Other Hollywood studios envy Pixar for to its appealing, carefully structured stories. Richard Neupert showed how that tradition goes back to the earliest years at Pixar. Even in demo films which were made to show off technological innovations, the makers tried to reveal how computer animation, even in its early, simple form, could create engaging tales. At a period when computer animation could only render smooth, simple shapes, the Pixar team found appropriate subject matter, with highly stylized characters in The Adventures of André and Wally B and Luxo, Jr.

Remarkably, these tiny films have balanced “acts.” Each is 80 seconds long and has a key action at exactly 40 seconds in: the entrance of Wally B and the moment when the little Luxo lamp jumps on a ball. Similarly, Red’s Dream‘s parts run 50-100-50 seconds. This care in timing continued with the features: Toy Story’s midpoint comes when Woody finally shifts strategies, realizing he has to work with Buzz. And what about Pixar’s perceived slump in recent years? someone asked during the question session. Neupert pointed out that Pixar’s founders have aged, and there may no longer be quite the sense of excitement and discovery pushing the team to surpass others and themselves.

Sometimes institutional traditions come into conflict. Petr Szczepanik’s talk traced in meticulous detail how screenplay development in Czechoslovakia was altered in the years from 1930 to the 1950s. Czech filmmakers developed their own system of moving from theme and story germ to final screenplay. But with the Communist takeover there came the demand to add the Soviet model of the “literary screenplay,” a detailed specification of scenes, dialogue, and the like. Filmmakers resisted this, preferring the customary and more flexible “technical screenplay” that was largely the province of the director. Petr mentioned new screenwriting trends pioneered by Frank Daniel that gave directors the authority to modify the literary format. By the late 1950s, filmmakers had found ways to make the literary screenplay a less rigid blueprint for filming.

Back in the USSR, the screenwriting institution found even the literary screenplay a difficult basis for mass output. Maria Belodubrovskaya’s talk focused on “plotlessness” as a rallying cry and term of abuse in the 1930s-1940s Soviet film. There were long debates about whether “themes” sufficed to make a film or whether you needed strong plots in the Hollywood vein. Film-policy supervisor Boris Shumyatsky urged the latter course, and the popular success of Chapayev (1934) seemed to support his case. By the late 1930s, though, Shumyatsky was purged and the tide turned against strong plots. Film executives found a concern with plot too “Western” and “cosmopolitan,” and annual film production became based on themes rather than stories. Most provocatively, Masha suggested a lingering influence of Soviet Montage storytelling, which based films on vivid but loosely linked episodes. She illustrated her case with an analysis of Pudovkin’s In the Name of the Motherland (1943), with its diffuse lines of action and sudden reversals and omissions.

Back we go

Scarface (1932).

Naturally, Madison wouldn’t be Madison without strong papers on the history of cinema, and many conference presentations suited the tenor of the joint.

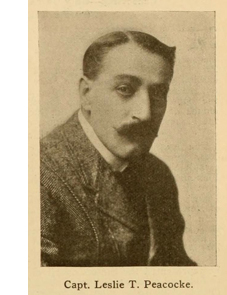

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen Curran offered an enlightening study of one of the least-known but most colorful figures in early American screenwriting, a man with the dashing name of Captain Leslie T. Peacocke. He was credited with over 300 screenplays, including Neptune’s Daughter (1914). He acted, directed, and wrote novels too. He was one of the first script gurus, writing magazine columns on the craft and eventually the early manual Hints on Photoplay Writing (1916).

Stephen surveyed Peacocke’s contribution to the emerging scenario market. Peacocke believed that successful screenwriting couldn’t be taught, but he could give hints about developing original stories, thinking in visual terms, and practical craft maneuvers like snappy names for characters. During the Q & A, Stephen added that a great deal of Peacocke’s rhetoric was aiming to raise his own profile in the industry. In conversation afterward, Stephen praised the Media History Digital Library and Lantern (flagged in an earlier blog) for immensely helping research into early film. Here, for example, is Peacocke’s 216-item dossier on Lantern.

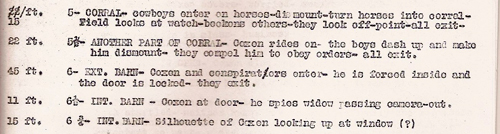

Andrea Comiskey argued that for the same period, we can study scripts and extrapolate craft practices that otherwise go undocumented. Her focus was the disparity between what manuals like Peacocke’s said and what actually got jotted down in working scenarios. Studying several screenplays from the American Film Company of Santa Barbara, she found that the manuals’ recommended stylistic approach was revised in the course of shooting.

The manuals proposed that each scene would be built out of a lengthy single shot (called, confusingly, a “scene”) which could at judicious moments be interrupted by an “insert.” An insert was usually a letter or piece of printed matter read by the characters, but it might also be a detail shot of a prop, hands, or an actor’s face.

In preparing scenarios, the writers assigned numbers to each “scene,” as the manuals recommended. But Andrea found that in the filming, the director and cameraman added shots, breaking down the action into more bits. This was, in effect, a move away from the strict scene/insert method and a shift toward what would become the classical continuity system. To maintain a paper record for the editor, the interpolated shots would be recorded and labeled in fractions. Instead of a straight cut from 6 to 7, the filmmakers might wedge in 6 ½, 6 ¾, and so on. Here’s an extract from Armed Intervention (1913), courtesy Andrea.

Strange as this sounds to us today, it was preferable to renumbering the shots, which could cause confusion. (Is shot 17 the original 17 or the later one?) The fractions kept the footage consistent with the scenario across the production process. So it turns out that (as usual?) filmmakers were a bit ahead of the screenplay gurus, even back in the 1910s.

Lea Jacobs asked a question about the transition from silent to sound film: How did filmmakers manage the pacing of dialogue? Silent movies had great freedom of pacing, while the shift to talkies seemed to many filmmakers to slow things down. Lea’s research indicated that two strategies for speeding things up emerged: creating shorter scenes and shortening dialogue passages within them. She reviewed how these ideas emerged in Hollywood’s own discourse in the 1930s and in certain films. In the first years of sound, scenes were rather long (often because they were derived from stage plays) and speeches were similarly extended. But in the 1931-1932 season, she argued, short scenes and quicker repartee became more common.

She traced the process in three films of Howard Hawks, from the stagy Dawn Patrol (1930) through The Criminal Code (1931), which opens in the new style but then turns to longer sequences, and then to Scarface (1932). The gangster film shifted toward shorter scenes and more laconic dialogue than did other genres, and Scarface displays this in full flower. Tony Camonte’s takeover of the South Side beer trade is presented in six harsh, violent scenes that add up to little more than three minutes. Workers in the sound cinema, it seems, were soon pushing toward that rapid tempo we identify with the 1930s.

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Storyboards have now entered academic studies. Chris Pallant and Steven Price offered some historical insights by comparing some early storyboards by William Cameron Menzie with those of early Spielberg films. When Menzies was storyboarding Gone with the Wind, he called it “a complete script in sketch form” and “a pre-cut picture.” Selznick’s publicity director characterized it: “The process might be called the ‘blue-printing’ in advance of a motion picture.” The striking revelation was that the storyboarding was not done after the script was finished. Menzies worked from the book, and the storyboard and script were created in parallel. Menzies’ storyboard for the 1933 Alice in Wonderland revealed a similarly elaborate process. It was 624 pages long, with one page per intended shot. Each page contained a sketch at the top, a paragraph describing the planned technological traits of the shot (such as lens length), and the traditional screenplay dialogue at the bottom. It’s hard to imagine many people other than a genius like Menzies being able to provide such a comprehensive plan for a film. (A sketch for Alice is on the right here. DB has written about Menzies here and here.)

Spielberg used sketches in addition to a screenplay from the start. Duel, surprisingly enough, was supposed to be shot in a studio, but the director insisted on working on location. The sketches he made for it do not resemble a traditional storyboard but instead are like pictorial maps framed from an extremely high angle. He also plotted out the paths of the vehicles with overhead views of the roads. The storyboards for Jaws were done from the novel at the same time that the script was being written, just as Menzies had done with Gone with the Wind. (The same thing happened with Jurassic Park.) Storyboards were vital, among other things, for telling the crew which of the four versions of the shark would be used. One fake shark had only a right side, another a left, and which one was needed depended on the direction the shark was crossing the screen. The speakers distinguished between the “working” storyboard and the “public” one. The public one is what sometimes get published, but it usually has each image cropped to remove the information about the shot (e.g., who will work on it) noted underneath.

Brad Schauer contributed to a roundtable on the American B film back when The Blog was in its infancy. He has been researching the role of B’s in the industry for many years, and he brought to our event some new ideas about them in the postwar period. His paper, “First-Run and Cut-Rate” showed that there were still plenty of theatres showing double bills in the 1950s and 1960s (DB can confirm it), and the market needed solid, 70-90 minute fillers. One answer was the “programmer,” or the “shaky A” that featured somewhat well-known talent, color, location shooting, and familiar genres (Westerns, swashbucklers, horror, crime, comedy, and science fiction). Shot in half the time of an A, with budgets in the $500,000-$750,000 range, programmers fleshed out double bills and sometimes broke into the A market.

What does this have to do with screenwriting? Brad decided to test whether Kristin’s ideas about four-part structure (here and here) held good with programmers. Looking at several, he came up with a plausible account that films like Battle at Apache Pass and Against All Flags simply compressed the four parts into short chunks, typically running fifteen to twenty minutes. In The Golden Blade, Rock Hudson formulates his goal (revenge) two and a half minutes into the movie.

Too few things happen?

La Pointe Courte (1955).

In most films, Agnes Varda said, “I find that too many things happen.” How can screenplay studies move beyond Hollywood’s jammed dramaturgy to consider the more spacious sort of storytelling we find in “art cinema”?

Colin Burnett offered a general overview of art-cinema norms that is somewhat parallel to our and Janet Staiger’s The Classical Hollywood Cinema. To a great extent, of course, “art films” differ from classically constructed films. They can be more ambiguous, more reflexive, more stylized and at the same time more naturalistic. They often replace a tight causal chain with episodic construction and nuances of characterization. The protagonists may have complex mental states; they may have inconsistent goals, or no goals at all; they may be passive; they may have shifting identities.

Yet Colin argued against claims that art films lack narrative altogether. “Art films offer reduced scene dramaturgy, rarely its complete absence.” They possess structuring devices comparable to Hollywood acts. A film’s large-scale parts may be based on a character’s development, on changes in space or time, or on variations of action and/or reaction. A question was raised as to whether such a broad category as art cinema could be characterized in such ways. Given the enormous range of types of films made in the Hollywood tradition, however, it seems possible that the art cinema could be described in a similar fashion. (For our thoughts on the matter, go here and here.)

A great many art-film strategies can be seen as stemming from modernism in literature and the other arts. As if offering a case study illustrating Colin’s argument, Kelley Conway focused on La Pointe Courte. Varda’s first film is now coming to be considered the earliest New Wave feature. But Varda wasn’t the prototypical New Waver. She wasn’t a man, she wasn’t a cinephile, and she took her inspiration from high art, not popular culture. A professional photographer who loved painting and literature, she brought to this film (made at age 26) a bold awareness of twentieth-century modernism. The result was a striking juxtaposition of stylization and realism, personal drama and community routine. In La Pointe Courte, we might say, neorealism meets the second half of Hiroshima mon amour.