Archive for the 'People we like' Category

How to write: Professor Westlake is in

Donald Westlake in 2001. Photo by David Jennings.

DB here:

There can be no question of my doing justice to the writing of Donald Westlake, also known as Richard Stark, Tucker Coe, and other cover names. For background you can go to his fine site or to Wikipedia, or this warm appreciation by Michael Weinreb. Here I just want to pay brief tribute to a writer who, like Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, seemed incapable of composing a bad sentence. Elmore Leonard gets deserved recognition as a laconic master of language, but Westlake was no less skillful. In some ways he was more ambitious and audacious.

He was astoundingly versatile. He wrote straight novels, erotica, and science-fiction, but fame came to him when he worked in three registers: terse toughness, wry comedy, and straight-up farce.

As Westlake he wrote psychological thrillers. Best-known, I think, is The Ax (1997), about a downsized executive eliminating the competition for jobs that might come up. Also as Westlake, he wrote comic crime novels. Many of these center on a gang of inept working-class thieves led, if that’s the word, by the hapless John Dortmunder. As Richard Stark, Westlake wrote very hard-boiled novels about Parker (no first name), an utterly emotionless professional thief, and his sometime assistant Alan Grofield.

Westlake rang many variations, both high and low, on the heist formula, and his plotting was fastidious. He made one story do for two novels by telling it from different viewpoints (Slayground and The Blackbirder, both 1971). The plot of one Dortmunder novel, Drowned Hopes (1990), was so complicated that it left interstices for Westlake’s friend Joe Gores to fill in an intersecting novel, 32 Cadillacs (1992).

Nearly all the Stark books have a strict four-part structure. In the early books, this is used to mark segments of time and to shift point of view. Elsewhere Westlake uses this pattern to rearrange blocks of time, so that part one takes place in the present, leading to a crisis. Parts two and three flash back to what led up to the book’s first chapter. Part four finishes up the action left hanging in part one. This layout was both a trademark and a self-imposed constraint that Stark-Westlake had to overcome in every book. Today’s young fiction writers could learn construction from these trim, no-nonsense tales.

At the moment, though, our topic is style. Here is the opening of Stark’s The Mourner (1963).

When the guy with asthma finally came in from the fire escape, Parker rabbit-punched him and took his gun away. The asthmatic hit the carpet, but there’d been another one out there, and he landed on Parker’s back like a duffel bag with arms. Parker fell turning, so that the duffel bag would be on the bottom, but it didn’t quite work out that way. They landed sideways, joltingly, and the gun skittered away into the darkness.

There was no light in the room at all. The window was a paler rectangle sliced out of blackness. Parker and the duffel bag wrestled around on the floor a few minutes, neither getting an advantage because the duffel bag wouldn’t give up his first hold but just clung to Parker’s back. Then the asthmatic got his wind and balance back and joined in, trying to kick Parker’s head loose. Parker knew the room even in the dark, since he’d lived there the last week, so he rolled over to where he knew there wasn’t any furniture. The asthmatic, coming after him, fell over a chair.

The economy is remarkable. There’s no explicit indication that we’re in a hotel room, or that Parker has been waiting for the invasion. This is in medias res storytelling, a Stark specialty. (Many of the novels begin with a “When…” clause.) In a couple more paragraphs, Parker gets the advantage and knocks out both men. “The asthmatic went down, hitting furniture on the way.”

The faintly amused tone here (being caught by “a duffel bag with arms,” kicking a man’s head “loose,” falling over a chair) is stronger in the Stark novels centered on Grofield. He’s a semi-professional actor who goes in for theft to finance his small-town theatre troupe. Parker is introverted, stoic, and borderline sociopathic, while Grofield is laid-back, good-natured, and quick with backchat. The opening of The Damsel (1967), parallel to that of The Mourner, shifts toward the deadpan comedy of the Dortmunder capers.

Grofield opened his right eye, and there was a girl climbing in the window. He closed that eye, opened the left, and she was still there. Gray skirt, blue sweater, blond hair, and long tanned legs straddling the windowsill.

But this room was on the fifth floor of the hotel. There was nothing outside that window but air and a poor view of Mexico City.

Grofield’s room was in semidarkness, because he’d been taking an after-lunch snooze. The girl obviously thought the place was empty, and once she was inside she headed striaght for the door.

Grofield lifted his head and said, “If you’re my fairy godmother, I want my back scratched.”

Opening one eye, then the other: The micro-action is as vivid as Rod Steiger or Eli Wallach playing up to us in a Leone film. The tone has changed too. Words like “snooze” wouldn’t show up in a pure Parker novel, I think. And now we get some scene-setting, but that’s because the wounded Grofield, flat on his back, can’t give us a tour of the room through physical action. What replaces Parker’s tussle is sexy banter. After the woman finds a suitcase full of cash, she gets suspicious. Grofeld explains: “I wear money.”

Finally, here’s extravagant burlesque from a non-Dortmunder story, Help I Am Being Held Prisoner (1974). The plot, about a practical joker who is thrown into prison among hard cases, is preposterously enjoyable, but again it’s the style that arrests, and convulses. The protagonist is accompanying Eddie, a demented ex-officer after they’ve broken out of the joint, sneaked onto a military base, and settled down in the mess for dinner.

“Speaking of landing on mines,” he said, “that reminds me of another funny story.” And he proceeded to tell it. Soon our food came, and so did the wine, but Eddie kept on telling me his reminiscences. Friends of his had fallen under tanks, walked into airplane propellers, inadvertently bumped their elbows against the firing mechanism of thousand-pound bombs, and walked backwards off the flight deck of an aircraft carrier while backing up to take a group photograph. Other friends had misread the control directions on a robot tank and driven it through a Pennsylvania town’s two hundredth anniversary celebration square dance, had fired a bazooka while it was facing the wrong way, had massacred a USO Gilbert and Sullivan troupe rehearsing The Mikado under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers, and had ordered a nearby enlisted man to look in that mortar and see why the shell hadn’t come out.

It began after a while to seem as though Eddie’s military career had been an endless red-black vista of explosions, fires, and crumpling destruction, all intermixed with hoarse cries, anonymous thuds, and terminal screams. Eddie recounted these disasters in his normal bloodless style, with touches of that dry avuncular humor he’d displayed during our hour at the bar. I managed to eat very little of my veal parmigiana–it kept looking like a body fragment–but became increasingly sober nonetheless. A brandy later with coffee, accompanied by a Korean War story about a friend of Eddie’s trapped in a box canyon for nine days by a combination of a blizzard and a North Korean offensive, who kept himself alive by sawing off his own wounded leg and eating steaks from it, but who later died in Honolulu from gangrene of the stomach, didn’t help much.

It’s a challenge to a novelist to tell us something funny is coming up and then to make it much funnier than we expect, turning it into a crescendo of slapstick violence. It’s partly the appositional phrases, which pile up mishaps, and partly the mock-heroic word choices. Would you (or I) come up with epithets like “endless red-black vista” or “gangrene of the stomach”? Could we pull off that satiric stab of a massacre occurring “under the mistaken impression they were peaceful Vietnamese villagers”? Extra-credit assignment: Diagram the last sentence. Could we write something so complicated and impeccable?

By these standards, most of our novelists, beach-book maestros or middlebrow bestsellers or literary lions, don’t cut it.

Many films have been drawn from Westlake’s books. Made in USA (1966) and Point Blank (1967) are probably the most famous, but both are very free treatments. Closer to the brusque Stark spirit is The Outfit (1974), while the French version of The Ax (2005, by Costa-Gavras) is quite watchable. I haven’t seen the recent Parker, with Jason Statham, yet. Sad to report, the several Dortmunder movie adaptations don’t make me laugh much. But Westlake had no illusions: “A movie is not the book it came from and in almost every case it shouldn’t be the book it came from.” Westlake wrote screenplays too, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990).

He died in 2008. He seems to have been the most easygoing, unpretentious writing machine you’d ever want to meet. The University of Chicago Press is republishing the Stark novels in handsome uniform editions, and there remain many other Westlakes that deserve unearthing. Read them for pleasure, for the smooth carpentry of their plots, and their cunning simplicity of style.

The top image, by David Jennings for The New York Times, is taken from the official Donald Westlake site, now maintained by his son Paul. My quotation from Westlake about adaptations comes from Albert Nussbaum, 811332-132, “An Inside Look at Donald Westlake,” Take One 4,9 (1975), 10-13. This postal interview, conducted by a prisoner at a penitentiary in Marion, Illinois, includes some insider information on Godard’s Made in USA.

The Outfit (1974), from the 1963 novel of the same name by Richard Stark.

Industrial strength

Edith Head costume sketch for To Catch a Thief. From Edith & Oscar: A Costume Exhibit, WCFTR website.

DB here:

Until the 1970s, academics interested in film seldom paid close attention to Hollywood as an industry. Some economists and historians of law were beguiled by the sight of an oligopoly eventually dismantled by Supreme Court decree. But these scholars weren’t particularly interested in the products of the studio system.

People interested in the movies took three positions. The most dogmatic, voiced by one of my grad-school professors, ran this way: “Money doesn’t matter.” That is, art will always triumph over business. If a movie is good, the circumstances of its making are irrelevant. And we study only good movies, so we needn’t consider the business.

Another view acknowledged the importance of the industry but saw it as a vague, overarching force. Creative artists were seduced by it or struggled against it. A powerful director like Chaplin or Hitchcock could control his work to a considerable degree. For the less powerful, the studios (along with censorship agencies) were barriers to creative work. They forced directors to bow to the demands of moguls or a debased public.

The third view was largely celebratory. The studios represented a wondrous confluence of talent at every level, from script to music, and the System mysteriously spun out marvels of drama, comedy, and spectacle: Hollywood as Gollywood. Researchers in this tradition ferreted out as much information as they could about the old days, infusing encyclopedic ambitions with fan enthusiasm.

What came to be called “Wisconsin revisionism” or “the Wisconsin Project” proposed some alternatives.

Auteurist in the archive

Corner of WCFTR office area. Photo: Mary Huelsbeck.

When I came to UW–Madison to teach in 1973, I was an auteurist with a taste both for Hollywood and foreign cinema. I knew relatively little about how the studio system functioned. Its machinations were simply factored out of my consideration. Directors, from Hitchcock and Hawks to Dreyer and Mizoguchi, were what loomed in my consciousness, and I wanted to spend my life studying what they had accomplished.

But contact with students, faculty, and campus personalities at Madison changed my thinking. There was The Velvet Light Trap, a defiantly unofficial magazine that ran special issues on all manner of non-auteur subjects, especially studios, periods, and genres. There were ambitious film societies like Fertile Valley and the Green Lantern, showing offbeat items. There were smart, well-informed grad students. There was the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, which housed thousands of prints, the center of my lustful thoughts both day and night. The WCFTR also housed vast archives of papers, scripts, photos, and other documents of Hollywood’s golden era.

Then there were Professor Tino Balio and Dissertator Douglas Gomery. My conversations with them, both in and out of the office, showed me that there were fruitful questions to be asked about the nature and conduct of the studio system. These two scholars, I think, more or less invented the rigorous historical study of Hollywood as a business enterprise.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Take Doug’s dissertation (and subsequent book). How did Warner Bros. innovate sound? Was Warners, as most accounts claimed, a threatened company, desperately driven to try a new technology to stave off bankruptcy? Doug answered the question in a revelatory way: The evidence pointed to Warners’ innovation of sound as a carefully calculated business decision made by a company that had already explored the technology and the market. In fact, WB was not going bankrupt, it was actually expanding into other domains, including radio. By using a traditional historical model of technological diffusion, Doug made the Warners’ decision intelligible. He served as a TA in my first course at Wisconsin, and our friendship proved to be a case of the student teaching the teacher.

Tino, who was presiding over the WCFTR, became another premiere scholar of filmmaking as a business. His books, anthologies, and book series brought immense attention to our collection of material on United Artists, Warner Bros., and RKO. He taught courses in the history of the industry, both survey courses and in-depth seminars. I think I learned more sitting on examination committees with him than I had in many of my grad-school lectures.

Many of the research questions asked by Tino, Doug, and their peers didn’t concern the movies themselves. Some did, though. I remember Cathy Root’s study of stars as strategies of “product differentiation.” More broadly, in the 1970s and early 1980s, some of us suspected that the Hollywood system of production, distribution, and exhibition could affect what then was called “the film text.”

As a result, Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I tried to show how Hollywood’s mode of production did more than simply limit gifted artists or yield pop-culture diversions. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), we tried to understand how the organization of production shaped work routines, technology, adjacent institutions, conceptions of quality, and other factors that did impinge on how the films looked and sounded. Over the years these aspects of filmmaking practice took off on their own, becoming somewhat detached from the industrial conditions that created them. When the studio system faded away in its classic form, the community’s notions of narrative construction, stylistic expression, professional practices, and other factors hung on. The economics changed, but the aesthetics persisted.

Now there are many people working to show how industrial factors interact with filmmakers’ creative choices. Kristin and I have continued these explorations in books and blog entries, extending them to other periods (e.g., the 1910s, the New Hollywood, the 1940s). I like to think that much of our work over the last decades has tried to blend the careful empirical and explanatory work of Tino, Doug, and others with the analysis of art and craft typical of film criticism. We can ask some questions that cut across the over-simple Art/Industry split.

Let a thousand projects bloom (motto, People’s Republic of Madison)

This exercise in autobiography was triggered by some recent events. One is the spiffy new website for the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Under its recent director Michele Hilmes and current director Vance Kepley, the Center has gotten a new jolt of energy. It’s promoting its vast collections in an attractive way and is starting to spotlight some that weren’t well-known. The selections are bolstered by informative program notes by Maria Belodubrovskaya, Booth Wilson, and others.

Certainly the Center’s heart, for historians of Hollywood, is the United Artists collection. This assembles United Artists business records from 1919-1965, scripts and stills from Warner Bros. and RKO, and several thousand film features, shorts, and cartoons, mostly from 1928 to 1948. Then there are the hundreds of named collections, provided by individual donors. The refurbished website calls attention to several of them: the personal and business correspondence of Kirk Douglas (some items now digitized), the Blacklist collection (six of the Hollywood Ten represented), the dazzling array of Edith Head’s costume designs (okay, I’m going a bit Gollywood). There are records for Otto Preminger, Walter Wanger (the basis of Matthew Bernstein’s biography), and Shirley Clarke. The restored Portrait of Jason was discovered in her collection.

Lately, needing information on Guest in the House (1944), I turned to the WCFTR screenplay by Ketti Frings. Her name looks like a Scrabble hand, but she turns out to be a fairly significant screenwriter, contributor to The Bells of St. Mary’s (1945), Dark City (1951), and By Love Possessed (1961). Some other day I must get around to prowling in the papers of Vera Caspary, an extraordinary person who is far more than the author of Laura (though I’d be happy just being that).

Beyond Hollywood, the Center holds major collections of Russian cinema and, more recently Taiwanese cinema. And if you must leave cinema behind for theatre, you can investigate Eugene O’Neill, George S. Kaufman, and many other luminaries. In sum, a resource to make you happy for decades.

A career and a conference

The expansion of the Center owes everything to Tino Balio, who served as director in its crucial years. It was he who acquired the UA treasures and many of the named collections. Access to the UA papers enabled him to write the definitive history of the company, but it also created a huge spillover effect: dozens of research projects were nourished by his pursuit of this collection—which came to us at a time when virtually no universities, not even those in LA, were seeking Hollywood corporate records.

So it’s fitting that, as the WCFTR redesigns its public profile, we see the publication of Tino’s Hollywood in the New Millennium.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

In a sense it’s a sequel to his earlier books, The American Film Industry (1976, 1985) and Hollywood in the Age of Television (1990). But these were anthologies, whereas this is through-composed. It’s most like his magisterial survey of the business strategies behind the art-film explosion, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 (2010): a careful study of a remarkable period in US film history.

Hollywood in the New Millennium charts the trends that characterize the last fifteen or so years of the American film industry. It surveys financing, production, distribution, exhibition, ancillary markets, and the independent realm. Tino analyzes the ways in which new technologies have changed all these areas, mostly to the benefit of the bottom line, but he also recognizes that technology can undermine the business, especially in the hands of what he calls “the I-want-it-for-free consumer.”

He surveys studio policies, attempts at synergy, and viral marketing. He traces the rise and fall of executives and is especially strong on the emergence of the overriding strategy of the tentpole picture aimed at teenagers and families. Since all studios belonged to entertainment conglomerates, the constant demand was for large-scale profits. For all its financial excesses, the tentpole strategy, Tino argues counterintuively, was an austerity measure.

By the decade’s end, every studio was in the tentpole business. Although the costs of producing and marketing such pictures were enormous, they were the only types that could perform on a global scale and generate significant returns. . . . The sure thing was a good hedge against a dying DVD business, the fragmentation of the audience, and the unknown impact of the internet and social media on Hollywood marketing practices.

In short, you could not ask for a more concise, reliable map of where Hollywood is today. The bibliography is expansive enough to inspire other researchers to dig into both printed and online sources.

Tino has exercised a remarkable influence on two generations of film scholars, but in an almost surreptitious way. Now every film student learns about the structure and conduct of the film industry, but few know that Tino played a pivotal role in making this sort of knowledge central to academic film study. Now in his mid-seventies, Tino has left a peerless legacy of research.

Speaking of research, our campus will be hosting a major conference that includes the WCFTR as a key component. The Screenwriting Research Network International is holding its annual gathering here on 20-22 August. I attended the Brussels SRNI conference two years ago and wrote about it here and here. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all. This is a stimulating bunch, and anyone interested in filmmaking would benefit from attending.

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

Keynote speakers this year are Larry Gross (48 Hrs, True Crime, We Don’t Live Here Anymore, Veronika Decides to Die), Jon Raymond (Old Joy, Wendy and Lucy, Meeks Cutoff , and several novels), and. . . Kristin!

The scholars are no less stellar and include Kathryn Millard, Richard Neupert, Jill Nelmes, Steven Maras, Riikka Pelo, Eva Novrup Redvall, Nate Kohn, Ronald Geerts, Andy Horton, Ian Macdonald, and a great many more. Go here for a complete program. You will be impressed.

Needless to say, among the guests are many UW alumni: Patrick Keating, Colin Burnett, Maria Belodubrovskaya (currently a faculty member too), Brad Schauer, Mark Minett, Mary Beth Haralovich, and David Resha. All of them have been steeped in archival research, centrally at WCFTR. Also home-grown are the conference organizers, J. J. Murphy (who blogs here) and Kelley Conway, who is finishing her book on Agnès Varda after immersion in that great lady’s personal archive. Another faculty member, Eric Hoyt, is curator of the remarkably full and free Media History Digital Library; expect him to divulge newer-than-new research sources and methods. I’ll crowd into the act with a paper tied to my 1940s book.

All in all, I see a pleasing continuity from my salad days, through forty years of teaching and viewing and writing, to this moment: a new Balio book, a sparkling shop window for the Center, and new generations of researchers eager to show that The Industry and The Art of Cinema aren’t always that far apart.

Earlier memoirs of Mad City culture in the 1970s-80s are here and here.

For more on the origins of Wisconsin revisionism, see my introduction to Douglas Gomery, Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States (University of Wisconsin Press, 1992) and this entry. We have a blog entry on Tino’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens here.

On the remarkable Vera Caspary (Wisconsin’s own) see not only her fine thrillers Laura and Bedelia but also her Bohemian autobiography The Secrets of Grown-Ups (McGraw-Hill, 1979).

Thanks to Steve Jarchow, CEO of Here Media and Regent Entertainment, for his many years of support of the WCFTR’s activities.

Kelley Conway, Tino Balio, and Lea Jacobs; Madison, WI September 2011.

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

Good, old-fashioned love (i.e., close analysis) of film

Kristin here:

On April 10, I received a message from Tracy Cox-Stanton, the editor of a new online journal, The Cine-Files. This journal is run out of the Cinema Studies department of the Savannah College of Art and Design. The message was an invitation to contribute to the fourth issue of the journal, of which, I must admit, I had been unaware until that time.

The invitation included two options. One was: “Offer a brief (1000-2000 word) reading of a film “moment” that considers how some particular detail of a film’s mise-en-scène (a prop, an actor’s gesture, an aspect of costume, a camera movement, etc.) illuminates the film as a whole, helping us understand the relationship between a film’s details and the overall “work” of cinema. We encourage the use of film stills.”

Having lived for decades in an academic publishing world which tended to discourage the use of film stills, I found this a cordial invitation indeed. Still, my initial thought was, if I had an idea for a study of a film “moment,” I should put it on our blog. We bloggers tend to become selfish about ideas for compact, easy-to-write analyses.

The other option, however, seemed more feasible: to respond to three questions as an online interview. It seemed a simple way of encouraging a promising new journal, and I accepted.

The Cine-Files is an appealing project. In place of the recent focus on cinephilia , which has often encouraged self-absorbed pieces in which film-lovers ponder the nature of their own love of film, “Cine-Files” implies good, hard study, with research resulting in files full of data that can result in informative, meaningful history and analysis.

It reminds me of The Velvet Light Trap in its heyday, though its format is quite different. In 1973, when David and I first arrived at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, graduate students in the young cinema-studies program and coordinators of film societies (showing 16mm prints by the dozen each night) published this extraordinary magazine. It was a combination of auteur worship, studies of studios, and genre analysis. The Velvet Light Trap was a film journal in an era when such things were rare and graduate students could be tastemakers.

The Cine-Files is similarly focused on films in their historical context. It is semi-annual and alternates open-topic and themed issues. Its first themed issue was on the French New Wave. Remarkably for a new journal, it attracted comments from experts such as Dudley Andrew, Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Richard Neupert. The newest issue, to which I contributed, is on Mise-en-scène. The topic for interviews, however, was a bit broader: “close readings.” The new issue, #4, has recently been posted, and my interview is here. There is also a call for papers for the fifth issue, an open-topic one, here.

Tracy has kindly agreed to our re-posting my responses to the three questions about close readings here. We have slightly modified the original post to suit this venue. We thank Tracy for a set of questions that provoked what we hope are interesting responses.

What is at stake in close reading?

To begin with, I don’t use the phrase “close reading.” I prefer “close analysis.” The notion of close reading is presumably a holdover from the 1970s and 1980s, when semiotics was a popular approach in film studies. Cinematic technique was thought to be closely comparable to a language, with coded units and grammar. Although there are some comparisons to be made between the techniques of cinema and a language, I don’t think the similarities can be taken very far.

“Reading” to me implies that interpretation is one’s main goal in looking closely at a film. I usually use interpretation as part of analysis, but it is seldom my main goal. Analysis, loosely speaking, to me means noting patterns in the relationship of the individual devices in a film (devices being techniques of style and form) to each other and figuring out why those patterns are there. What purposes do they serve?

What is at stake in close analysis depends on what sort of analysis one is doing. I’m assuming here that the subject is scholarly or semi-scholarly analysis intended for publication. My own purposes for analysis fall into at least these categories:

1. The simplest reason to analyze a film would be to find out more about it because it’s appealing or intriguing.

I’ve written essays on Jacques Tati’s Les Vacances de M. Hulot and Play Time, in both cases because I admired them and wanted to be able to understand and appreciate them better. I go on the simple assumption that we can only be entertained and moved by films to the degree that we notice things in them. Complex films can’t be thoroughly comprehended on a single viewing or even several viewings. Sometimes you may need to watch them more closely, not in a screening but on a machine, like a flatbed editor or a DVD player, that lets you pause and slow down the image.

2. One might analyze a film in order to answer a question, often to do with the nature of cinema in general.

My essay on “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” as the title suggests, arose more from my interest in a particular, unusual device, the “lying flashback,” than from a particular admiration for the film.

3. You might want to make a case that a film is significant and suggest why others should pay attention to it.

One example would be the rediscovery over the past few years of Alberto Capellani’s French and Hollywood silent films. On this blog site, I posted two entries, “Capellani ritrovato” and “Capellani trionfante,” analyzing some scenes to support the claim that Capellani was one of the most important stylists and innovators of the era from 1905 to 1914.

A very different case came with The Lord of the Rings trilogy by Peter Jackson. I had written a book, The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood (University of California Press, 2007), primarily on the marketing and merchandising surrounding the film and on its many influences. I would not claim Jackson’s film to be a masterpiece, but there was such a great backlash against it, mostly by literary scholars of Tolkien, that I thought it might be worth counterbalancing their opinions. I wanted to make a modest defense of the film as containing some excellent passages and effective decisions concerning the adaptation process. So I wrote two essays based on that argument. (See the codicil to this entry for references.)

4. Close analysis can be vital for writing about film history.

For example, David and I have studied films closely to determine the stylistic and narrative norms of specific times and places. We’re also interested in finding films that were innovative in relation to those norms. Rather than examining a single film closely, such an approach involves analyzing many films to find commonalities and divergences. For example, David has studied the norms and innovations of modern Hong Kong cinema (Planet Hong Kong, Harvard University Press, 2000; second edition available online at Observations on Film Art).

Another such project was my Storytelling in the New Hollywood: Understanding Classical Narrative Technique (Harvard University Press, 1999). There had been many claims in academic and journalistic writings that the norms of Hollywood storytelling had declined after the end of the studio era and that we were now in a post-classical era. Such claims didn’t tally with what I was seeing in the best Hollywood films, the ones held up as models within the industry. I did case studies of ten such films, dating from the late 1970s to the early 1990s, going through each scene by scene. I showed how classical techniques like protagonists’ goals, dangling causes, dialogue hooks, redundant motivation, and other traditional norms were still pervasive in modern Hollywood. I chose the ten films because I liked them, but others would have made my point equally well.

Please tell us about something that couldn’t be understood without a frame-by-frame attention to detail.

I don’t think most close analysis goes to the minute detail of examining a film frame by frame. Sometimes it’s necessary, especially with French and Soviet films of the 1920s or with some experimental work. There can be lots of ways of looking closely at the parts of a film and relating them to other parts.

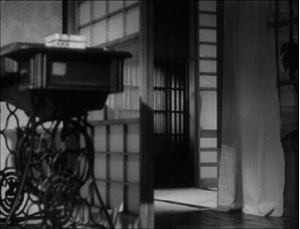

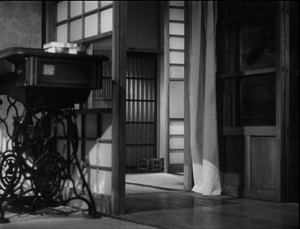

Take a simple example, in my essay on Late Spring, I reproduced eleven shots across the length of the film that include a sewing machine off to one side of the frame–or, in one case, the space where the machine had been. No two of these shots are the same, though they often are only small variations on each other, with the machine closer or further from the camera, sometimes on the left, sometimes the right, and so on. I even missed a couple, the second and third shots immediately below, so there are actually thirteen variants. (DVDs do have their advantages. It’s not so easy going back and forth across a film looking for such repetitions in a 35mm print.)

The series culminates late in the film, after the daughter has married and left her widowed father living alone. We see a similar framing along a corridor, and the space formerly occupied by the sewing machine is empty. (See below.)

The daughter doesn’t use this sewing machine in the course of the action, and no one mentions it. Many viewers probably vaguely notice that there is a sewing machine in the house. A few may notice its eventual absence late in the film. But even someone who watches the film over and over and at some point notices that there is a meaningful pattern of the sewing-machine shots would not be able to describe it. I suspected that the sewing-machine shots were small variations on each other, but were there some repetitions? How many were there? I was only able to get a good understanding of how the motif worked by photographing all the shots (or so I thought at the time) and comparing them side by side—and having the luxury to reproduce all eleven frame enlargements in my book.

What point is there in analyzing such a motif in detail? If we admire Claude Monet for taking infinite trouble to capture tiny changes of light on haystacks or lily-ponds, why not devote the same respect to one of the cinema’s greatest directors? To go back to my point at the beginning, we can only appreciate a film to the extent that we notice things about it. I take it that the critic’s job is to notice such things and point them out for the enrichment of others who don’t have the time or inclination to do close analysis.

How do digital technologies allow us to engage in “direct” criticism that bypasses traditional written criticism?

One obvious answer is that digital technologies allow anything that could be published in printed form to be offered online. Whether written for consumption via the internet or already published and then scanned to be posted, online criticism offers some obvious advantages. There is no lag in publication time and no need to hunt for a press. Of course there are disadvantages too: no real guarantee of long-term survival, often no academic reward for publishing through a non-refereed process. David and I have posted many entries involving close analysis on this blog. (I discuss the history and approach of Observations on Film Art in an essay for the first issue of the online journal, Frames Cinema Journal: “Not in Print: Two Film Scholars on the Internet.”)

Perhaps more interesting is the question of what critical tools digital technologies offer for analysis itself. In past decades, David and I had to rig up elaborate camera-and-bellows systems to photograph frames from prints of films—as well as to travel far and depend on the hospitality of archivists to gain access to those prints. Nowadays DVDs and Blu-rays bring hitherto rare films to the critic, and readily available players and apps allow for easy capture of frames for illustration purposes. If the essay or book based on close analysis using such tools is to go online, it also becomes practical to reproduce a great many more frames as illustrations than would be possible in a print publication. David’s e-book edition of Planet Hong Kong permitted him to publish most of the illustrations in color, an option that would have been prohibitive in a university press volume.

The possibility of using short clips as illustrations in an article or book is very promising, especially once electronic textbooks get past the trial stages. I made a modest contribution to the use of clips as examples for introductory students with “Elliptical Editing in Vagabond”; this was done with the cooperation of the Criterion Collection and posted by them on YouTube in 2012. Other extracts appear as proprietary supplements for Film Art: An Introduction. Since then, David has offered three online lectures analyzing editing, the history of film style, and the aesthetics of CinemaScope; see our Videos listing on the left.

Video essays analyzing films are still a new format but show great potential. Their usefulness will depend on how the issue of copyright plays out. At this point, I’m hopeful that showing clips as part of an analytical study will become established as fair use, as clearly it should be. Being able to use moving images complete with sound as well as still frames from films will be an extraordinarily useful tool.

I hope that critics using digital tools will take the trouble to create analyses as complex as one can achieve through description in printed prose. This would mean editing together stills and short segments from across a film, recording voiceover comments, adding graphics where useful, and so on. Close analysis of this type will always be a labor-intensive process.

The analyses mentioned in this article have been published in collections. “Boredom on the Beach: Triviality and Humor in Les vacances de M. Hulot,” “Duplicitous Narration and Stage Fright,” “Play Time: Comedy on the Edge of Perception,” and “Late Spring and Ozu’s Unreasonable Style” appear in Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988). “Stepping out of Blockbuster Mode: The Lighting of the Beacons in The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003),” was published in Tom Brown and James Walters, eds., Film Moments (British Film Institute, 2010), and “Gollum Talks to Himself: Problems and Solutions in Peter Jackson’s Film Adaptation of The Lord of the Rings” appeared in Janice M. Bogstad and Philip E. Kaveny, eds. Picturing Tolkien: Essays on Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings Film Trilogy (McFarland, 2011).

Late Spring (1949).