Archive for the 'People we like' Category

“We didn’t have a sense that VERTIGO was special”: Doc Erickson on classic Hollywood

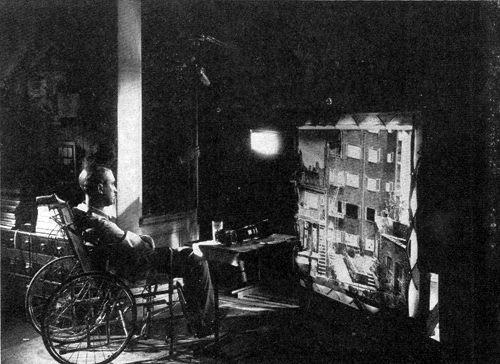

Rear Window (1954); illuminated transparency used to create the lens reflection.

Note: This entry was nearly finished when Roger Ebert died on 4 April. I had intended to send it to him in advance. I think he would want me to post it as I’d planned–just before this year’s Ebertfest.

DB here:

On 17 April, about 1500 people will gather at the Virginia Theatre in Urbana, Illinois, for a celebration of movie love known as Ebertfest. Among Ebertfest’s many guests will be C. O. “Doc” Erickson.

This genial man, who visits Ebertfest each year, is a Hollywood veteran. He was production manager for Alfred Hitchcock, Sidney Lumet, John Huston, Anthony Mann, Roman Polanski, and Ridley Scott. In later years he was associate or executive producer on Chinatown, Urban Cowboy, Popeye, Blade Runner, Looking for Bobby Fischer, Groundhog Day, Kiss the Girls, Windtalkers, and many other projects.

In short, he was an eyewitness to film history. During our visits to Ebertfest Kristin and I have often talked with Doc about his career, and last year I interviewed him for an hour. I thought it was time we set down some of the things we’ve learned. I’ve supplemented Doc’s remarks to us with quotations from Douglas Bell’s 2006 detailed, book-length interview with him.

Setting the scenes

Sunset Boulevard (1950).

Doc began working for Paramount Pictures in December 1944, a year after his graduation from the University of Illinois—Champaign-Urbana. This young man, not yet twenty-one, stepped into the studio that would harbor, across the next few years, The Lost Weekend, The Blue Dahlia, The Strange Love of Martha Ivers, Unconquered, I Walk Alone, A Foreign Affair, Sorry, Wrong Number, The Big Clock, The Heiress, The File on Thelma Jordan, The Furies, Sunset Boulevard, and several Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, and Martin and Lewis comedies.

Initially he worked on estimating the budgets for back-lot and set construction. Doc’s unit would try to give the director some leeway. “Ultimately, it wasn’t [a director’s] fault if the set went over budget. . . . We had to try to get enough money in there so that it wasn’t going to go over budget, because then we’d catch hell.” Then Doc and his colleagues would monitor the building of the set to make sure that the specifications were followed and the budget was adhered to.

Doc moved to stage management and supervision, which required him to plan how a production’s sets were arranged in a sound stage. Four or more sets would have to be fitted together, jigsaw-fashion. Doc would try out arrangements by shifting cutout sets on something like a bulletin board, marked with entrances, walls, and power sources. This was called “spotting the sets.” Spotting was much easier in the days of overhead lighting; lighting from the floor, which became more common as the decade went on, posed extra problems.

Once used, the sets might be dismantled, with different departments rescuing what they could use again. A whole set might be saved for another picture (“fold and hold”). B-pictures recycled sets from A pictures. At the other extreme, ornate interior sets might use units drawn from luxurious houses that had been dismantled. From New York mansions came pieces that were shipped to Hollywood and resassembled to create a salon or ballroom.

Paramount’s back lot included big standing sets, including a train station with some cars on the track. “Then, of course, you had pieces of the train in the scene dock, that could be dragged out and assembled on the stage.” A street at the south end of the lot was used for Westerns and featured a mountain that blocked the view of the adjacent RKO studio.

I’ve long been struck by the fact that articles from the classic period seldom talk about the look of sets for ordinary rooms. So I asked: What colors would be found on the sets in black-and-white movies? Doc smiled. “Black and white—or rather, shades of gray.” Sometimes a bit of green would be added. (I’ve read that sometimes snow was painted yellow to make it dazzle.) Pause and think about how hallucinatory it must have looked: actors moving through a three-dimensional black-and-white movie.

The crew was expected to average fifteen to twenty setups per day, at a period when shooting a top-line feature took anywhere from seven to twelve weeks, or even more. The Paramount policy was to press ahead and finish with a set quickly, even if not every shot was taken. Retakes were likely to be close views of the actors and could be picked up later without need for the full set. This flexibility was feasible because most productions were still shot inside the studio walls. Despite the trend toward location shooting in the late 40s, Doc says, “We weren’t off the lot very much.”

The 1940s saw the rise of the hyphenate filmmaker, and this trend was vigorous at Paramount. The studio roster boasted screenwriter-directors Preston Sturges and Billy Wilder and several director-producers, including Cecil B. DeMille, Mark Sandrich, Mitchell Leisen, and John Farrow. At Paramount, Doc recalls, “The director was king.” No wonder that one of the most kingly figures of the period wound up there for several years.

A step up

The Misfits (1961).

Doc had moved into the role of assistant unit production manager for Secret of the Incas (1954), directed by Jerry Hopper and starring Charlton Heston and Robert Young. His new job involved managing the day-to-day work of filming as a liaison between the production office and the shoot. A production manager works closely with the assistant director to keep the work on schedule and within budget.

When Hitchcock made his five-picture deal with Paramount and was preparing Rear Window, his assistant director, Herbert Coleman, found that all Paramount’s established production managers had been assigned. Coleman asked Doc to take the job, and Hitchcock approved. Doc’s experience with budget estimating and set supervision made him a natural choice for promotion.

Doc supported Hitchcock on several films, becoming a guest at the director’s home and traveling with him. After finishing Vertigo, Hitchcock shifted to studios that had their own personnel for production management. Hitch offered Doc a place on his television series, but Doc moved on to other Paramount pictures: “I wanted to remain in the feature film world.” He worked in Manhattan with Sidney Lumet on That Kind of Woman (1959). Doc admired Lumet’s meticulous planning of every shot, as well as his insistence on table readings of the whole film before shooting.

Doc then teamed up with John Huston. In 1959 Huston was trying to launch The Man Who Would Be King, and for location scouting he took Doc and other team members on a forty-day trip around the world, paid for by Universal. But that project was put on hold. Doc went on to manage production for The Misfits (1961), Freud (1962), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967). On the latter two films, Elizabeth Taylor lobbied for Montgomery Clift—winning on Freud, losing on Reflections. (Brando got the part.)

Knowing my interests, Doc pointed out some of Huston’s directorial touches, including some striking uses of deep space. In the image above, Montgomery Clift’s quarrel with the rodeo judge is framed in the car window while Marilyn Monroe frets that he could have died in his fall from the bull. Doc also thinks that Huston showed adroit staging in the Reflections scene showing Brian Keith wiping lipstick off his mouth while Elizabeth Taylor, in the back seat, uses the rearview mirror to help her repaint her lips.

The movie industry was pushing toward ever more spectacular projects, and Doc sometimes went epic. After a production manager on 55 Days at Peking (1963) quit, the film’s editor, Robert Lawrence, suggested Doc. The film’s direction was credited to Nicholas Ray, but the bulk of the footage was shot by Andrew Marton. There followed Doc’s stint on The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964). He recalls Anthony Mann’s excellent eye for composition. The most tangled production was Cleopatra (1963), which had begun shooting in 1960 and was plagued with constant delays. Doc was there for the last eight months of shooting, up to August 1962. He worked under Lewis Merman, the Fox production manager (“one of the greatest human beings I’ve ever known”). Merman was also known as Doc, so the production had both a Big Doc and a Little Doc. It needed even more docs.

Hitch

For my current research I asked Doc a lot about 1940s studio practices, but I couldn’t avoid touching on what everybody asks him about. How was working with Hitchcock? Hitchcock productions have been chronicled in detail by many writers, so I’ll just pick some bits that Doc brought out for me.

On Rear Window (1954), Doc’s expertise in squeezing sets into a sound stage came in handy. The script demanded that the camera be confined to Scottie’s apartment and that we see only what could be seen from that room. Remarkably, Doc recalls no matte shots being used on the production. The apartment, the courtyard outside, and the apartment building opposite were all installed on a single stage.

Doc was struck by the lighting limitations of this complex and confined set. The color film stock was quite slow, and so illumination levels were very high. He told Douglas Bell:

We had to pour so much light into those apartments, up where Raymond Burr was, it almost put him on fire. It was terrible. Or you would never be able to see him, from where we were shooting. . . . But today it would be nothing, it would be a cinch.

Lens length was also a problem because the camera couldn’t easily simulate the telephoto view of the apartment across the courtyard. Doc found a way to mount the camera outside the window to get a little closer to the opposite building and suggest the enlargement provided by Scottie’s long lens.

Hitchcock had claimed he would need only twenty-four days to shoot Rear Window, but it ran to thirty-six, and its cost was considerably beyond what he had estimated. So great was Hitchcock’s standing in the industry that Paramount didn’t object, knowing the result would be a major picture. Doc was on the set every day. Hitchcock would position the actors and frame the shot, but then return to his chair to watch.

Hitchcock liked Doc and picked him again for To Catch a Thief (1955). For this they left the studio and shot on the Riviera for several weeks—Doc’s first location shoot. After the on-site filming was finished, Hitchcock returned to Paramount for studio scenes and Doc stayed to oversee helicopter shots of the roadways with special-effects specialist Wallace Kelly. The team followed the famous Hitchcock lists and storyboards for such second-unit footage.

Without a break Hitchcock drafted Doc for The Trouble with Harry (1956). Originally to be set in England, the story was transposed to New England. Despite some location work, there were a surprising number of studio exteriors (as are quite obvious to our eyes today). Doc supervised the building of woods on Stage 14, but then scattered around leaves brought in from Vermont and New Hampshire.

Doc was involved in scouting locations in Marrakech and London for The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956), along with assisting Coleman and Hitchcock in the usual way. Hitchcock clashed with John Michael Hayes on the project, and according to Doc, Steven Derosa’s account of the contretemps in Writing with Hitchcock does justice to the complexity of the situation.

Doc’s memories of the master’s next production, Vertigo, are detailed, but they and other participants’ accounts are chronicled in Dan Auiler’s Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic. What I found surprising were two of Doc’s responses to the project. Doc found that the production went very easily. He thinks that was because he had learned so much about location shooting with the overseas demands of To Catch a Thief and The Man Who Knew Too Much. My second surprise: “We had no sense that Vertigo was special.”

I’m out of step with the world’s critical consensus. I wouldn’t consider Vertigo the best film of all time, or even the best film by Hitchcock. (My votes would go to Shadow of a Doubt, Notorious, Rear Window, and Psycho. All seem to me perfect, endlessly exhilarating pictures.) To a great extent, I think that American Hitchcock never stopped being a 40s director, so I tend to see Vertigo as an uneven mix of plot elements and visual ideas from that wild era. Good as the film is, I think, the expository scenes are rather flatly filmed and lack the flair that Hitchcock brought to such scenes in his earlier films.

But thanks to the undeniable brilliance of many other scenes, along with the revolution of taste promoted by the Cahiers du cinéma critics and the long suppression of the film (making it a sought-after treasure), Vertigo has become a holy grail of obsessional cinema. Its plot premise has fed cinephiles’ fantasies. In the history of taste, a fairly creaky tale of murderous deception has become the ultimate vessel of filmic fascination. One hero’s delusion now epitomizes all movie-made illusion.

Give Doc the last word: “When we finished Vertigo, we never thought of it as being the film that everybody thinks it is today. It’s become bigger than life itself.”

Thanks to Doc Erickson for affable and informative conversations.

Being mostly interested in the Old Hollywood, Kristin and I didn’t question Doc about his work of more recent decades. Those activities are covered in Douglas Bell’s extensive interview, recorded in An Oral History with C. O. Erickson (Los Angeles: Academy of Motion Picture Arts, Margaret Herrick Library, 2006). I’ve drawn much information from this volume. I thank Jenny Romero, Special Collections Department Coordinator at the Herrick Library, for facilitating access to it, and to Kristin for examining it for me during her recent visits to Los Angeles.

For a detailed account of the division of labor on 55 Days at Peking, see Bernard Eisenschitz, Nicholas Ray: An American Journey, trans. Tom Milne (Faber, 1993), 378-389. Andrew Marton, who took over the shoot after Nicholas Ray was dismissed, estimated that sixty to sixty-five percent of the finished film was his work. See Andrew Marton Interviewed by Joanne D’Annunzio: A Directors Guild of America Oral History, 413-418.

Herbert Coleman’s book The Hollywood I Knew: A Memoir: 1916-1988, revisits his AD work with Hitchcock in considerable detail, and many of the anecdotes he recounts involve Doc Erickson. For more on the production of Hitchcock’s films, see Patrick McGilligan’s Alfred Hitchcock: A Life in Darkness and Light and Bill Krohn’s Hitchcock at Work.

Without any planning, the last six months or so have been this blog’s Hitchcock period. The entries include items on Dial M for Murder (screened at the Toronto International Film Festival last September), on David O. Selznick, on the first Man Who Knew Too Much, and on the rise of the suspense thriller during the 1940s. On Lumet, for whom Doc also worked, you can see this entry. The production photographs in today’s entry are taken from Arthur S. Gavin, “Rear Window,” American Cinematographer 35, 2 (February 1954), 76-78.

Kristin and Doc Erickson, Ebertfest 2009.

Cheers, R.

We owe Roger an enormous debt. Since we met in 1999 at the Arts Club of Chicago, Roger has been the most generous and eloquent supporter our work has had. In our visits to their festival, Roger and Chaz welcomed us into their community and introduced us to people who have become good friends. Roger came to our Wisconsin Film Festival twice, and his presence gave it a burst of energy. In Roger and Chaz we found a couple engaged passionately in the act of living in, and for, each other.

Our larger debt is to the lessons Roger taught us, and thousands of others: Writing about film can exemplify writing about life. Friendship and good humor must inform everything you do. Punishing health problems need not kill your appetite for experience, for fellowship, and for the life of the mind.

In Roger’s memory, each of us offers some personal reflections.

Kristin here:

As with so many other people, my first acquaintance with Roger was through his and partner Gene Siskel’s television review shows. I’m not sure when David and I started watching. At first we were partly attracted by the fact that each review included a clip from the movie. TV reviewing was such a new form that the studios didn’t put together montages of shots to provide the reviewers. You got to see an actual scene as it appeared in the film, something that could give you a sense of whether or not you wanted to see the film. Later the edited-together shots from various parts of the film came to be more like a trailer than a sample. They don’t tell you much about the film. But Gene and Roger did, so we kept watching.

We noticed the fact that Gene and especially Roger would often promote films that were in release but not likely to be known to most of the show’s viewers. Small independent films and foreign films, which the pair urged people to try and see in theaters or, increasingly, on video. These were the same sorts of films that became the core of Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. Few reviewers writing for a mass audience have bothered regularly to call attention to worthy independent and art-cinema fare.

When we met Roger in the late 1990s, the first thing that struck me was that in person he seemed exactly the same as on TV. On the air he didn’t put on a public persona or try to entertain us at the expense of giving us less information about the film in question. Those were the early days of the infotainment boom. As its name suggests, infotainment coverage means that the reporters and reviewers feel obliged to be as entertaining as the news (or pseudo-news) they present. I think of another reviewer in the early days, Gene Shalit, who started out presenting reasonably informative review segments on the Today Show. Increasingly, however, his eccentric appearance, with large, frizzy hair and an oversize mustache, combined with his breezy, pun-filled delivery made his segment into a sort of comic interlude that barely qualified as a film review. In other words, the opposite of Roger.

Over the next several years, David got to know Roger better than I did. He helped squire Roger around during his 2003 visit to the Wisconsin Film Festival and wrote introductions to his books. I was in the early years of working on an Egyptian archaeological expedition, and in 2003 I was struggling to get my big project on the Lord of the Rings franchise (published as The Frodo Franchise in 2007) off the ground.

During that time I managed to go with David to the Overlooked Film Festival and enjoyed it very much. There Roger’s zeal for introducing general audiences to relatively obscure films was boiled down to its essence. The enthusiasm of the loyal attendees was contagious, as was Roger’s joy in sharing his love for the films and giving the audience access to the stars and filmmakers who were his friends.

From 2003 to 2006, I was dashing around the world, interviewing people in New Zealand, Los Angeles, Silicon Valley, London, Copenhagen, and elsewhere for my book. By the spring of 2006 I had talked with 75 people and acquired the knowledge I need to write most of my chapters. Game producers and designers filled me in on the video-game aspect of the franchise; festival-heads and distributors enlightened me on the impact of the trilogy on the international independent film market.

But there was a crucial piece of the puzzle missing. My fourth chapter was to be on the rise of modern infotainment journalism, covering such topics as press junkets, the replacement of paper press kits replaced with EPKs (electronic press kits), and the rise of making-of promo films on cable. I knew how press junkets work, with their endless strings of short interviews where the reporters ask the same questions over and over–and the fact that studio employees did the filming and editing of the interviews. I had talked to cast and crew members about the Lord of the Rings junkets. (Ian McKellen: “Someone will come forward and say, ‘I know you get asked all sorts of questions. I’m not going to ask you the questions everybody else asks you, so I’m going to say, “What is the question that you’re most asked?”‘”) But I didn’t know much about how such things got established historically or how they looked from the viewpoint of the journalist interviewer. Unfortunately, nobody had written a history of press junkets.

It occurred to me that Roger was an expert on such subjects. His career as a reviewer got going in the mid- to late 1960s, when the studios were increasingly using press junkets, and he had not only witnessed but participated in the expansion of film coverage from print into television. Roger happened to be slated to visit the Wisconsin Film Festival in the spring of 2006. I asked him if he would be willing to let me interview him on such topics. Despite a heavy schedule, he agreed. The only time he could fit me in was over breakfast on April 2. I went to his hotel and talked with him for about half an hour. (David came to pick us up and snapped the photo above; my recorder is under the list of questions I had concocted. Roger has toast and coffee, back in those happy days when he could still eat.)

The result was everything I could have hoped. With his razor-sharp memory, Roger gave me invaluable historical information and insights. For example, I asked why reporters ask questions to which they already know the answers:

Because the sessions are so short, and because the nature of television is that you have to get them to say it. They get pretty stupid questions. For example, I may well know who Hilary Swank plays in Million Dollar Baby, but it doesn’t work on television unless she says, “I play a woman who wants to be a boxer.” You have to have her saying it. So you say, “Well, tell me about this character you play.”

It was a delightful and fruitful interview, supplying that last piece of the puzzle. It also happened to be the last interview I did before finishing the book a few months later and sending the manuscript to the press.

That June, Roger had his disastrous health crisis, ending up in a coma until August. Of course, he lived on to give us a tremendous amount of insightful writing on film and his own life and his view of the world in general. But I was very grateful to have had that interview with him while he could still speak. As anyone who has done much live interviewing knows, it’s very different from interviewing by email. The conversation takes unexpected turns and generates questions that weren’t on the original list. I’m still thankful for that interview, not just for the selfish reason that it enhanced my book. I’m also glad that I got some of the valuable information that Roger had in his memory but had never included in his voluminous writings. He was a living document of modern film history, and inevitably much of what he knew never got written down. At least I captured a bit of it.

I think that interview gave Roger a better sense of me as a film scholar. We also happened to start this blog later that year, in late September. I doubt that Roger had time to read every entry, but he read many of them and helped get the blog established by linking to it. We didn’t like to pester such a busy man, but we notified him when we posted something that we thought related to his interests. (My skepticism about 3D matched his, for example.) Here’s the last time he linked to one of my entries, with his characteristic generosity and the occasional typos that resulted from the speed with which he poured out his thoughts on FaceBook and twitter:

I think he must also have realized that, despite the fact that our interview was on a recent blockbuster franchise, one of my specialties is silent cinema. I got invited to the 2007 Overlooked Film Festival to be one of the “expert group of colleagues” who were to help fill in for Roger during his recuperation. I introduced Raoul Walsh’s Sadie Thompson and after the screening was on the panel that chatted with the three members of the Alloy Orchestra.

In 2008 the event changed its name to what most of us called it already, Ebertfest. I was now sort of the unofficial silent-film expert. I got to introduce a luminous print of von Sternberg’s Underworld, which I had never seen in 35mm, and to lead the post-screening discussion with the Alloy members. (My program notes for the event are here.) The same thing happened the following year with The Last Command. It’s a pity that the Alloy team never accompanied Docks of New York at Ebertfest, completing the survey of von Sternberg’s trio of silent masterpieces.

I missed the 2010 festival, needing to be at the site of Tell el-Amarna for my Egyptology work. But I returned in 2011 to introduce and discuss a screening of the nearly complete version of Metropolis, recently restored.

In 2012 I again needed to be in Egypt during Ebertfest, so the 2011 festival was the last time I saw Roger in person. But we kept in contact by email. That could be a delightful process, as David shows in the second half of this entry.

DB here:

Werner Herzog, Roger Ebert, and Paul Cox, Ebertfest 2007.

From different perspectives, I’ve set forth my sense of Roger’s contribution to film culture. On this site we’ve covered Ebertfest over the years, and I reviewed Life Itself. In addition, the University of Chicago Press has generously made my introductions to Awake in the Dark and The Great Movies III available online (here and here). After Roger’s death last week, I wrote a brief tribute for the UW Antenna site. Still to come is a valedictory piece for Film Comment, to be available in print and online.

So today, when Roger is ceaselessly on our minds, I thought: Why would anyone want to listen to me when they could listen to him? You can hear (and watch) him in the vast video archive of Siskel & Ebert. But maybe I can bring you his voice in another way.

Combing through a decade’s worth of emails, I found some bits that seem worth sharing. A subject line “From Roger” always marked an email worth reading, and the inevitable sign-off, “Cheers, R.,” left you wanting more. I can hear him speaking these words, even in the years when he had no voice. Maybe you will too.

Apparently almost all G-rated animation will now be in 3-D! I hear IMAX will show nothing but 3-D (via digital). No more celluloid! Traditional IMAX process is dead. The vulgarians are at the gates. (2008)

Have you seen Chop Shop? I’m showing it at Ebertfest. Sort of an American indie neorealist picture. And in 70mm, a new print, Baraka. Best Blu-ray I’ve ever seen. Most critics liked Coraline even more than I did. (2009)

Just saw Ponyo. The opening undersea sequence is miraculous. Manohla Dargis was right about Perfect Getaway: A good B movie. (2009)

I hated Les Miz, of course. Falling dirges, rising dirges, ditties, boilerplate. (2013)

I am often guilty of getting carried away by films that will not stand the test of time, although I do think that The Dark Knight will continue to be interesting. (2009)

I always said I would not retire until I had a book about Scorsese. Now I do, and I can’t retire until I have one about Herzog! (2008)

I remember Scorsese saying he watched Black Narcissus at least once a day for a week. (2012)

[I wrote that Donald Richie was recovering his health:] So I hear! Walking around the room, likes the new place with English-speaking help, health on the mend. What a dear man. His film of The Inland Sea is wonderful but the book and his Journals are really special. So honest and matter of fact. (2010)

[On images in a blog entry on Andrew Sarris:] How moving it was to see the photos of old friends like Arthur Knight and Hollis Alpert. Remember when the Saturday Review was eagerly awaited? I met Arthur and Marianne in 1968, on the notorious Warner/Seven Arts week-long junket which flew planeloads of critics to the Bahamas. I was a kid. They immediately invited me to their home and through them I met many Hollywood figures.

God, Arthur loved his pipe, and his sacramental martini formula. I never drank a martini except at his house, and there nothing else. The way he made one approached the psychedelic. Marianne was a costume designer. . . . They bought a house on the beach at Malibu when such things could be had for less than millions. Their Saturday open houses were gatherings of interesting people, including some (like Blake Edwards’ doctor) later immortalized in films. (2012)

[In the midst of Ebertfest, Roger took time to write:] I’ll write more later….but be sure to buy the News-Gazette before you leave town. There’s a wonderful photo of Kristin, Richard [Leskovsky], and Nina [Paley] (2009).

[When I posted this entry about the Jem movie theatre in Harmony, Minnesota, Roger commented on this picture.]

That photograph, seemingly so artless and matter-of-fact, speaks deeply to me. The color, the shadows, the girls in conversation. (2012)

Chaz and I are at Cannes, I having survived the trip in surprisingly good shape. Lots of big names, but as Frémaux says, “They have to prove themselves every time.” (2009)

In high school, I went to popular movies with dates and attended the Art Theater mostly alone. In college there was a period when I sort of stopped going to popular movies—more art films and film societies. (2011)

I have a lifelong policy of never making lists of anything except my annual Best 10. Can’t tell you how much time I saved by not compiling Halloween movie lists. (2011)

I am so happy the festival is approaching and Kristin and you and I can sit again in the same room with good movies. (2010)

[When I replied that Kristin couldn’t attend that year because she was needed for her archaeological dig in Egypt: ] And my Egyptian correspondent Wael Khairy will be in Urbana! So the balance of the earth won’t be altered. He is a very gifted film critic. . . . He has two more weeks to wait until the ban on his writing is lifted. It was imposed after he led a (successful) effort against the censors to remove the Arabic subtitles from the CENTER of the screen on Avatar. (2010)

[On the musicians in Woodstock:] I, like you, was not focused on rock in the 1960s. I had to ask Chaz who some of the performers were. These days, I know nobody. (2009)

Do you remember that nice Indian kid sitting next to you at Ebertfest? I met him through my blog when he was 15. He had been making films since he was 6. His father was going to accompany him…but unexpectedly died shortly before. His dad approved of the visit, so Krishna came with his lovely mother and sister. I love this kid. (2012)

You know where the Westerns have gone for an audience? Video games, that’s where…as long as you look for the right type of western. John Wayne. John Wayne. I think it was Montaigne who said: “Everyone needs a name like that.” (2009)

[I wrote him that watching movies is good, but maybe reading is better:] You know, I think I agree with you. I doubled my “reading” by adding audiotapes of books that don’t call out to be intensely read. I’ve listened to about 100. The single most spellbinding performance I’ve heard is Sean Barrett doing Perfume. (2008)

[I sent him a link in which David Brooks returns from an expedition into the Midwest, recalls his admiration for White Castle, and declares his new preference for Steak ‘n Shake]: Yeah, but he strays off the point pretty quickly. And I don’t know anyone who prefers White Castle to S ‘n S….although late boozy nights in my 20s often called for a bag of sliders. Californians are passionate that In ‘n Out makes better burgers than Steak ‘n Shake. I contend that the very names of the two chains dramatically contrast the styles of sexual intercourse in the two regions. (2012)

I have been honored out! Above all I need to focus on writing. Sounds harsh, but everything’s an effort these days…. (January 2013)

[The University of Chicago Press sent him my Foreword to Awake in the Dark and he replied]: I felt as if, after 38 years of plugging away, someone had understood just what I have been trying to do. I work for a newspaper, I get categorized as a newspaper reviewer. I am proud to be one. But I have also tried to stretch the limits of the form. I think of myself as being a teacher as much as a writer, and I like my forum because it gives me a lot of readers. . . .

That you mentioned Shaw took my breath away. I have been reading Shaw for 40 years, starting by reading every one of his Prefaces, from which I learned that it is quite all right to stray entirely from the subject, or approach it from an unexpected angle. In the last few months I’ve been reading his collected music criticism. I don’t know a thing about music, but that was an advantage, because I was able to focus on his language and strategy. His use of paradox and under- and overstatement is audacious, and I like the way he states even his most extreme positions as if they are simple common sense. (2005)

The last message I got, on 15 March 2013, referred to the 2013 Ebertfest schedule. It contained only one word.

Hooray!

Cheers, R.

On the block adjacent to the Virginia Theatre, off South State Street, Champaign, Illinois.

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert at 4 Star Video Heaven, Madison, Wisconsin, 2003.

Kristin and David:

Roger died today. We can’t do him justice in such short compass, but we do want to acknowledge him and his life. He was an unstinting friend to us, and a great and good force in American film culture.

The Sun-Times obituary is here.

Later 4 April: Jim Emerson’s personal tribute is here.

5 April: Chaz Ebert’s statement is here.

6 April: Jim Emerson has gathered a constantly expanding collection of tributes here.

7 April: Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press offers recollections here.

Roger and Chaz Ebert, Ebertfest, Urbana, Illinois, 2010.

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

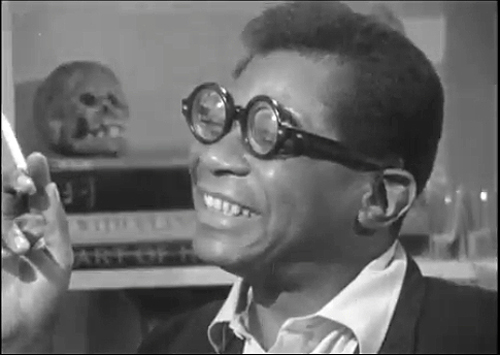

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).