Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Donald Richie

Donald Richie and students. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

DB here:

He died last week, aged 88.

What was his life about? The public dimensions involved, of course, his status as unofficial spokesman, principal gaijin, the gatekeeper and guide to anyone interested in Japan. He hosted grad students as genially as he played tour guide to Truman Capote and Susan Sontag and Jim Jarmusch. I don’t know of any other situation in which an American (from Lima, Ohio, no less) became the spokesperson for a foreign culture. From the 1950s into the 2010s, in a stream of writings and lectures, he interpreted how the Japanese lived, worked, thought, and created. Although he wrote about everything from landscape to tattoos, he became best known as the supreme expert on Japanese cinema. His particular love was the postwar “Golden Age” of the late 1940s through the early 1960s.

Tokyo/Hibiya crossing; Dai-Ichi Building, 1947.

Japan was still terra incognita to Westerners when he came there in 1947. When the outer world demanded to understand this very strange place that had fought so tenaciously against America, there arose a generation of interpreters. Of that cadre, though, he stands out as the man you can’t quite place.

The oldest of the group was Edwin Reischauer, who worked largely in international policy. A somewhat younger man, Donald Keene, became the dean of Japanese literary studies. Keene has provided translations and magisterial overviews of the Japanese novel, drama, and poetry. An almost exact contemporary of Keene’s is Edward Seidensticker, who has been a renowned translator and cultural historian.

Only a little younger was our author, who came to Japan in the Navy and soon became a prolific writer. Yet his work didn’t fit the mold of the other American experts on Japan. He was neither a traditional scholar (he read little Japanese, though he spoke it fluently) nor a pure journalist (he refused to be tied to topicality). He remained resolutely in-between. What academic would have the brass to sum up “The Japanese Way of Seeing” in a seven-page essay? Yet what journalist would write subtle critical monographs on Ozu and Kurosawa?

In my copy of Partial Views: Essays on Contemporary Japan, he wrote: “For David, from Donald, particularly pp. 157-205.” On those pages you find his “Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura.” It’s a fertile survey of recurring themes and techniques in Imamura’s films. In the hands of a professor it could certainly become a tightly argued book. Was his inscription telling me that, when he wanted to, he could execute criticism with an academic accent? If so, it was unnecessary. I didn’t need convincing. I think he could have done whatever he wanted.

What he wanted, I think, was to join the tradition of European belles lettres. He earned his living by writing, and doubtless his championship typing skills steered him toward the quick turnover of daily deadlines. More deeply, I think, he found the shorter piece suited his flair for precise evocation. Even in his books, his approach is essayistic, faceted. His tone—thoughtful but not severe, conversational, projecting wide knowledge and good sense and humane modesty—won the reader by its quiet conviction that the subject was important. This essay wouldn’t be the last word; indeed, he would likely return to the subject years later, testing out new ideas. Much of his output consists of occasion-based pieces, and any of these might be recast, cut, or expanded. A craftsman knows how to recycle scraps and spruce up old projects.

This commitment to fluent reflection on daily changes, along with a quality of seeing everything around him afresh, put him in the tradition of the Continental “man of letters.” He was an aesthete, a moralist, and a bit of a dandy. His natty clothes were like his literary style, crisp and elegant but not flamboyant.

His preferred mode was description. He was convinced that whereas Westerners struggle to probe the depths, “The Japanese realize that the only reality is surface reality.” During a visit to Madison, he was delighted to find a translation of the Goncourt brothers’ journals. I couldn’t help thinking that he took them as a model of the urbane curiosity and pellucid prose he cultivated.

Above all he was interested in people. He was an excellent observer but also a well-tempered listener. He chatted with barbers, students, masseuses, neighbor ladies, potters, delivery boys, executives, and celebrities. He listened to their complaints, their dreams, and their reports on the texture of their lives. Sometimes they quarreled with him or disappointed him. But each one gave him a glimpse of the wavering mirage that was Japan, or at least his Japan.

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952).

His writing skills worked on a big canvas in The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959). He wrote the text while his collaborator Joseph Anderson, who read Japanese, provided the research. The book came at just the right moment, when Americans were starting to appreciate the power of this nation’s cinema. To this day, despite many specialized studies of directors, periods, and genres, it remains the standard overview of one of the great national film traditions.

Just as important, for me at least, was The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968). The first edition, a magnificent buff volume with razor-sharp illustrations and double-column text, is a triumph of book design, as solid and imposing as the films it canvasses. Along with Robin Wood’s works on Hitchcock and Hawks, it showed that cinema could be studied with intellectual seriousness. To the auteurist’s search for the guiding themes of a director’s vision, the Kurosawa book brought a sharp eye for technique and a direct access to the artist himself. (Our author’s first visit to a movie set was to Drunken Angel.) And it proved that a great film could sustain shot-by-shot scrutiny.

Turn to any chapter and you will see a probing intelligence. For Ikiru, we get a detailed layout of image/ sound relations in the nighttown sequence, bracketed by Watanabe’s funeral. The analysis carries us to this conclusion:

He has become much more than simply dead. Just as, dying, he learns to live; so, dead, he becomes more alive for others than he ever was before.

The Kurosawa book remains an exceptional achievement in sympathetic imagination. The critic is so finely in tune with the creator’s sensibility that each chapter illuminates and amplifies the dynamics of the film. There are other ways of understanding Kurosawa, but this book will remain the compass that orients us to this essential director’s career.

Floating Weeds (Ozu, 1959).

There were other books, of course. Among the best is the rare 1961 Japanese Movies, published by the Japan Travel Bureau. It is a compact survey of the major directors working in the postwar era. You sense that its intense aesthetic appreciation of particular films arises from portions cut from The Japanese Film. Here the critic is working at full stretch, and his thoughts on Naruse, Mizoguchi, and others are still worth reading. In its fifteen pages on Ozu, then unknown in the West, lie the seeds of his book on the director.

We have him to thank for our awareness of Ozu. He persuaded the reluctant Shochiku company to release the films in Europe and the US. His ten years of effort were crowned by the release of several Ozu films in New York in 1971-1972. At that point, largely as a result of accidental access, Tokyo Story emerged as the director’s official masterpiece. Soon afterward there appeared Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), another monograph informed by personal acquaintance with the director.

The Kurosawa book dealt in depth with each film, but this took a more horizontal and modular approach, tracing a skein of similarities across Ozu’s work. As one would expect, the emphasis falls on the postwar films, which were more easily available and which the author saw as they were released. (“Revisionist” takes on Ozu, and Japanese cinema as a whole, would soon return to the 1920s and 1930s and find there an earlier Golden Age.) The chapter layout tends to assume that Ozu films are more uniform than they are, but for its attention to themes and script construction in particular Ozu is indispensable. The author’s love for the films shines through every page.

It’s sometimes said that he brought Japanese cinema to the west, but apart from his championing of Ozu, this is inexact. Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, and Gate of Hell won an Academy Award in 1955. Daiei and Toho studios exported several films to Europe and America, while distributor Thomas Brandon sought to bring less-known Kurosawas to the US. The Japanese Film arrived at a propitious moment in 1959, when it could capitalize on the wider circulation of titles. Not until the 1970s was America to see a resurgence of interest in Japanese cinema, thanks to the Ozu releases, the Ozu book,the circulating programs sponsored by the Japan Film Library Council, and the efforts of Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films.

Still, our author did something quite important. By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture. Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic.

Although his major books remained essential for film lovers and film courses, it’s fair to say that he got a second wind in recent decades. He won a wide and keen following with his commentaries and liner essays for Criterion DVD releases of Japanese classics. The outpouring of grief after his death comes in large part from viewers who knew him best as a warm, calm voice talking through scenes of Tokyo Story or When a Woman Ascends the Stair or, surprisingly, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar. He adjusted well to the new world of video. He treated it as a new conduit for his commitment to civilized discussion.

Five Filosophical Fables (Richie, 1967).

So much for the public man, writer and speaker and animator of film culture. Another side of him was an intense erotic interest. On your first meeting, he made sure you knew what he found appealing. In the Journals, cruising and pickups blend with a swarm of local details of landscape and custom, although consummations are elided.

I had noticed that his suteteko, being thick cotton, are still damp from the swim, and so I suggest he take them off and hang them on a branch to dry. He does so.

*

Later, in the afternoon, I take a train around the coast. . . .

The juxtapositions between moments of artistic ecstasy and sexual passions give the journals a collage-like snap.

[Hiteki] got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. . . . Does everything but only, I feel because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. . . It represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 October 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves.

The diaries we have are very polished products, the results of much rewriting, and stretches are calculated to render the guilt-free sexiness that the wanderer finds all around him. Consider the finesse of this passage about a visit to Aoshima island:

Later we shop in the empty tourist arcades and buy some beautiful and indecent objects—cups you turn over to discover a coupled couple, an articulated vagina disguised as a shell, and a sake cup with a mushroom-shaped penis attached. One is to suck the sake from the mushroom head.

Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.

The surfaces might be rough. The journals record his enjoyment of living near Ueno Park, where the homeless and the prostitutes gather at night. He strolls through them, meeting the occasional cop and seeking, as he puts it, someone who can typify Japan in all its contradictions.

Beautiful and indecent: You can find this mixture in some of the experimental films he made too. The most inoffensive of these, Wargames (1962), was circulated among American film societies during the 1960s, but others are more audacious. In the allegorical satire Five Filosophical Fables (1967) a young man abandons a snooty party, strips to the buff, and strolls smiling through Tokyo streets, past the sea, and into the countryside. Cybele (1968), a documentary of an avant-garde theatre performance, presents an orgiastic rite of sex, degradation, and bloody sacrifice.

Roppongi Hills, Christmas 2010.

He was assailed by bouts of illness across two decades, but he seems never to have lost his buoyancy and spiky wit. He was especially mordant on the New Japan. He notes that the thrusting high-rise apartments of the 1980s bubble offer more for Godzilla to whack. “Originally [he] had to content himself with a mere Diet building.” Manga and the Sony Walkman were very much alike, he maintained. Each offered not visual or aural stimulation but a convenient way to shut oneself off from the ugliness of a money-grubbing society: solitary withdrawal amounted to a critique of contemporary life. With mock pathos he told of a salaryman so preoccupied with talking on his cellphone that a passing subway train snagged him and carried him off, the handset dropped squawking to the platform.

The humor could be self-deprecating. One of our conversations:

DB: I liked The Inland Sea.

DR: I traveled for three months and wrote it in three weeks.

DB: And I read it in three hours.

DR: You took too long.

When asked if he loved Japan, he replied, “That’s complicated . . . I love Tokyo.” Yet by the end of his life, his city had become alien to him. His Japan Journals begin by sketching the vibrant colors of a blasted landscape returning to life.

Winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The final entry in the journals is dated nearly sixty years later and records a 2004 trip to his old neighborhood. Tansumachi of 1947 had become the fashionable Roppongi Hills district, “the new Japan—gargantuan, expensive, and wasteful.” A Louise Bourgeois statue looms over the pavement like a tarantula. He recalls the street once named Dragon’s Way and the friend’s house that used to stand at that corner. He knows that his nostalgia must seem tiresome and he acknowledges that rapid change is itself a Japanese tradition, a sort of high-tech version of the Floating World. Yet he cannot resist denouncing the Disneyland that the old place has become. He finds no arresting color or light in this world.

In just a number of years every place will look like it, and this kind of economic expediency will be the rule, as will those cute nods in the direction of retro and trad, that comedy team of contemporary design. Here, under the spider, I look into the future which is already here.

He was well aware of living in-between. Today we might say that he was perpetually “other,” too aesthetically sensitive for a mercantile society, too protective of tradition in a period of lightning change, too gay for straitlaced America, too eccentric and independent-minded for assimilation into his adopted nation. Painful as these tensions must have been, he proudly accepted being fundamentally out of place. At the end of one essay he claims his motto to be that of Hugo of Saint Victor:

The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.

Extracts from Richie’s writings come from The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968 and later editions), A Lateral View (1992), and The Japan Journals, ed. Leza Lowitz (2005). Richie’s films are available on DVD as A Donald Richie Film Anthology from Image Forum Video. See also The Donald Richie Reader (2001), ed. Arturo Silva, for a varied collection of pieces, including articles on how he came to write about film, and his lively tour Tokyo: A View of the City (1999), with photos by Joel Sackett. The photo of Tokyo/ Hibiya crossing comes from the Journals, the shot of Roppongi Hills from Tokyofashion.com.

For a provocative review of The Japan Journals, see Richard Lloyd Parry’s “Smilingly Excluded.” Kim Hendrickson, who produced Richie’s DVD commentaries, provides a tribute on the Criterion site. A list of his commentaries and liner notes is on this page.

For more on how Japanese films came into the United States, see Chapter 6 of Tino Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973.

Thanks to Tony Rayns for conversations and assistance.

Elsewhere on this site are other Richie-related entries, particularly here and here.

P.S. 25 February: Karen Severns has set up a Donald Richie tribute page here.

Donald Richie at the grave of Ozu. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

Digital projection, there and here

Galeries Cinéma banner, Brussels, 2012.

DB here:

The Cinéma Arenberg, in the splendid Galerie de la Reine, has long been a mainstay of Brussels film culture. Since 1939, the lovely Art Deco theatre was what we Americans call an art-house. Over the years Kristin and I visited the city, the Arenberg’s autumn and spring schedules featured recent releases, but every summer the programmers plunged into plucky repertory programs. While the multiplexes ran Hollywood blockbusters, the Arenberg provided 90 or so classics and little-known releases under the rubric of Écran Total. It was here, for example, that I saw von Trier’s The Kingdom and resaw Vanishing Point. Four years ago I left a little note about the three titles I watched during my last day in town: India Song, Serpico, and Darjeeling Limited. That trio gives you a sense of how varied and interesting the programming was.

The Arenberg closed down at the end of 2011, but the cinema has reopened under new management as Galeries Cinéma. It didn’t sponsor an Écran Total season this year. Instead it offered brand-new releases on its three screens, along with some children’s programs.

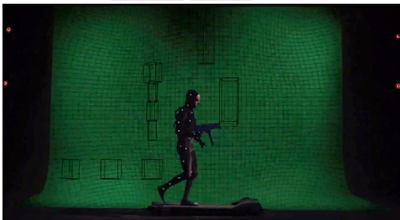

Most notable for me this time was Leos Carax’s Holy Motors. Whatever you’ve heard about this film is probably accurate. I found it an exhilarating, frustrating, and continuously provocative descent into Surrealist role-playing. It’s a tour of cinema genres and an anthology of bits of other movies, from Marey to Franju, and not forgetting Carax’s own. Especially evocative were the poetic fusions, such as the way that the body stocking Oscar dons for digital motion-capture evokes both ninja outfits and the leotards of Feuillade’s Vampires. Carax films Oscar’s SPFX exercise in a way that connects Muybridge to video games and recalls the exuberantly spasmodic scene in Mauvais Sang in which Denis Lavant races madly down the street to the accompaniment of David Bowie’s “Modern Love.”

Whether you find Holy Motors infuriating or beguiling, you won’t forget it.

Exquisitely shot on digital capture, Carax’s film was given crisp, bright digital projection at the Galeries. And speaking of digital projection. . . .

The new issue of Film History, devoted to digital technology’s impact on filmmaking and film culture, includes Lisa Dombrowski’s article “Not If, But When and How: Digital Comes to the American Art House.” It’s a very fine survey of all the issues facing the art-film community at this moment. Lisa reviews the major technological and financing conditions before going into depth on a case study of three art theatres in Miami. The author of a very good book on Samuel Fuller, Lisa knows how to tie together industrial and aesthetic issues skilfully.

Another young scholar, this one at the Free University of Brussels, has concentrated on the digital transition in Europe. Since 2005 Sophie De Vinck has been studying how the conversion of theatres fits into European film policy. The result was her 2011 thesis, “Revolutionary Road? Looking back at the position of the European film sector and the results of European-level film support in view of their digital future.” The thesis, running to a whopping 769 pages, is an immense resource, and not just for people interested in digital cinema. Sophie surveys the history of national and international support of the Western European film industry, from production through exhibition, and she provides both a broad context and very specific analysis.

Part of her argument is that the “diversity” aimed at by subsidized filmmaking hasn’t been matched by diversity in audiences. But digitization offers a new chance to show films outside the dominant forms of commercial cinema and perhaps attracted new sectors of the public. “Every innovation usually brings with it possibilities for new or smaller sector players to strengthen their competitive position.” Her examination of how digital conversion affects small and art-house venues provides a complement to Lisa’s research.

I wish I’d known about Sophie’s thesis when I was writing the blogs that became Pandora’s Digital Box, but at least I can signal her work now. Best news of all: Sophie has generously made “Revolutionary Road?” available under a Creative Commons license here as a pdf. Full of valuable statistics and well-honed observations, her work helps us understand how the contemporary European film industry has survived and sometimes flourished over the last fifty years.

Cinema Arenberg, Brussels, 2008. The original design of the curved doorway and neon sign was restored in 2005-2006.

The indispensable site Cinema Treasures has a brief entry on the history of the Cinéma Arenberg/ Galeries. More extensive information can be found in Isabel Biver’s luxurious survey, Cinémas de Bruxelles: Portraits et destins, which I wrote about in an earlier entry.

P.S. 1 August 2012: I just learned from Gabrielle Claes that Giovanna Fossati’s book on digital restoration in film archives, From Grain to Pixel, is now available for free in pdf form here. It’s well worth reading.

German detour

DB here:

A bad back kept me from Cinema Ritrovato, as Kristin explained in her Bologna blog entry. So I spent that week at home fiddling with the Film Art entry, and starting another one that I posted most recently, on the swirl of controversy around the Orpheum Theatre here in Madison.

Thanks to some exercise, chiropractic, and a nice dose of painkilling medication, I was able to embark on the second phase of the trip: My annual visit to Brussels for its Cinédecouvertes festival and for some research in the Royal Film Archive. But this visit was different from earlier ones because I took time off to visit colleagues in Germany.

My first stop was Mainz, a lovely cathedral town that’s also the capital of its state. My hosts were Andreas Rauscher and Oksana Bulgakowa of the University’s Department of Film, Media, and Empirical Cultural Studies.

Andreas has with two colleagues written a book on The Simpsons (Subversion in Prime Time). Once very controversial (because of its many pictures from the series), it’s now headed into its third edition. Andreas also works extensively on narrative theory in film and media. Oksana, Chair of the Department, is an old friend of ours who has done a great deal of work in classic Soviet cinema. She has written a comprehensive biography of Eisenstein and has launched an ambitious program studying gesture in cinema and culture. It was a pleasure as well to re-meet Norbert Grob, a key player in a recent collection devoted to “minimal cinema” (you know I like the cover), and to meet Armin Jäger, who has written us with corrections and suggestions for Film History: An Introduction.

My talk was the last in a series on the future of film studies. I usually hesitate to participate in exercises like these, which tend toward the gaseous. But when Andreas assured me he wanted me to discuss how modern digital culture, particularly the Web, affected my research, I felt more able to say something. So I did, drawing together what I’ve learned through and about the online world. The results were recorded on video and will be posted online.

Before the talk I enjoyed ambling around Mainz with Andreas and his colleagues Bernd Zywietz (left, above) and Renate Kochenrath. Renate made me feel old: She had attended my 2003 lecture at the University as an undergraduate. But she compensated by (a) giving me a spare umbrella; and (b) showing me the devil’s dung in a corner of the beautiful cathedral.

I even got to meet a fan, Alexander Gajic, who had reviewed my Pandora e-book. Like me, he stalks autographs, but how do you autograph an e-book? He found a digital-to-analog solution.

The night before, I had walked a bit around town with Andreas, Oksana, and Dietmar Hochmuth. I had the sense of being in a Murnau film: winding streets overseen by magnificent towers half-medieval and vaguely futuristic.

After my 1 ½ days in Mainz, I had only a day in Frankfurt. My host was Vinzenz Hediger, who explores the intersection of film history and media history. (He knows, in particular, a lot about the history of the Hollywood industry.) Here he is with two sterling Steenbecks his department retains.

The film department at Goethe University is housed in a stunning complex, now known as Poelzig-Bau or the IG Farben Hochhaus.

It has quite a history. The great architect and set designer Hans Poelzig (the Grosses Schauspielhaus in Berlin, sets for The Golem) created it for the IG Farben chemical trust at the end of the 1920s. The largest office building in Europe, it became a center of Nazi technology, including the development of the Zyklon-B gas used in concentration camps. The complex housed the US armed forces HQ from 1945 to 1995. According to Colin Powell’s autobiography, he first met Dick Cheney in these halls.

At Frankfurt, I gave two talks. The first was a variant of a party piece I’ve worked up, on narrative innovation in Hollywood during the 1940s. I was happy to see so many students turn up on a very pleasant day. I was also happy to see that Heide Schlüpmann, now retired, had arranged for a display of film, actual film, to be a permanent part of the lecture room.

My other Frankfurt talk was at the Deutsches Filminstitut Filmmuseum, recently redone as a dazzling modern facility. Walk in, and you’re in a dark box, in which the displays glow enticingly, like pods in a space station.

The first floor is devoted to pre-cinema, with many hands-on toys and gadgets. It culminates in a Lumiere display. The second floor roams across film history, with an emphasis on storytelling. Eras mingle: Next to a velvet dress from Visconti’s Leopard you might see a Giger Alien design. And it’s big.

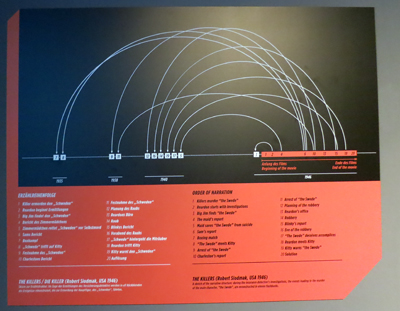

There are many interactive displays, letting you recut a sequence or remix a soundtrack. The third floor is for touring exhibitions, this time one devoted to Film Noir. Close to my heart was a diagram of the time shifts in the plot of The Killers.

Like New York’s Museum of the Moving Image (which we visited here), the Frankfurt museum has acknowledged the need to educate a new generation of movie lovers. What once were temples drawing aging cinephiles to worship are now filmic Exploratoriums, invitations to play with the curious thing we call movies.

More on Germany–well, the obscure German silent movies I’ve been watching in Brussels–in an upcoming post. For now, back to work in Belgium. And to the tasty snack treats portrayed below, although in somewhat smaller portions.

Thanks to Andreas Rauscher, Vinzenz Hediger, and Michael Kinzer for background information on their institutions.

Kristin has just published her own account of our experiences going digital, here.

Summer art displays in Parc de Bruxelles/ Warandepark, Brussels.

P.S. 22 July: Renate Kochenrath and her colleagues have created a striking site documenting art cinemas in the Rhineland-Palatinate region. The photos are quite beautiful.

Octave’s hop: Andrew Sarris

La Règle du jeu (The Rules of the Game, 1939).

DB here:

The death of Andrew Sarris last week isn’t just a saddening moment for those of us who admire exhilarating film criticism. It also reminds us how much American culture can owe to a single person.

Everyone who writes about Sarris writes about how they came to know his work. It was that powerful, and if it hit you young, you were never the same. (You never hear about the sixty-year-old who suddenly becomes an auteurist.) The period of his greatest impact was the 1960s-1970s when, to borrow a phrase from Dave Kehr, movies mattered. But his influence has lingered, powerfully, a lot longer.

I think that the best way to honor Sarris is to take his ideas–not just his opinions, but his ideas–seriously, so that’s what I’ve tried to do in this tribute. First, though, some comments that are obligatory in any discussion of Sarris.

Obligatory autobiography 1

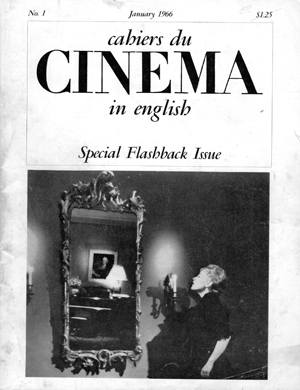

1963: When I was sixteen I wrote to various film magazines and asked for sample issues as a “prospective subscriber.” Surprisingly, several answered, and I amassed a few copies of Film Quarterly, Films and Filming, and Movie. No gift from the land of film journals was more propitious than that fateful issue 28 of Film Culture entitled “American Directors.” It was the first draft of what would become Sarris’ 1968 book, The American Cinema.

Issue 28 was a dangerous item to give a kid. It contained what Georgie Minafer calls “touchy chemicals.” At first I was baffled. There were those famous categories: How to distinguish “Lightly Likeable” from “Less Than Meets the Eye”? Who were Budd Boetticher, Tay Garnett, and John M. Stahl? What did it mean to say that Robert Montgomery “executed a charming champ-contre-champ joke in Once More, My Darling”? To me it was all Expressive Esoterica. Here was a cave of mysteries, but it hinted at treasures.

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Sarris’s filmographies were packed with titles I’d never heard of. How could I catch up? Around 1955, the studios had begun selling their pre-1948 titles to local television stations. By the next year, people living in major cities could tune in five or six movies a day. At the forefront of TV sales was the financially precarious RKO, which sold over seven hundred titles to an outfit called C & C. C & C packaged the library as 16mm TV prints under the rubric of “Movietime.”

Auteurism owes a good deal to the 1950s-1960s equivalent of home video, the thousands of 16mm prints floating around local TV stations. In Manhattan, WOR-TV screened their films under the rubric “Million Dollar Movie.” The same film might run once or twice every night for a week (and twice or more on weekends). Without benefit of WOR or New York’s revival houses, I was still able to use Rochester television to sample some of the titles that Sarris had listed, especially those given in big caps. (Italicizing must-see items didn’t show up until the book version.) Sarris’s essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” was published in Film Culture in 1956, the same year that the RKO library began to be syndicated and Kane was reissued in theatres around the country.

I did wind up subscribing to Film Culture. It was the least I could do to pay them back.

Obligatory autobiography 2

Fall 1965: At a state college up the Hudson, the English department hosted a debate on contemporary American movies. The adversaries were Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, both just coming into the national spotlight. One freshman came early and sat with comic earnestness in the front row, a spot he would fetishize later.

Kael was witty and acerbic, tossing off judgments with a wave of her cigarette holder. The Cincinnati Kid was the best of the current crop; Jewison showed great promise. She was riding high because I Lost It at the Movies had come out that spring and was greeted with hosannas. The New Yorker review contrasted her with “the far-out Sarris.”

He didn’t look so far-out. In a crumpled suit, he was resolutely uncharismatic, looking mildly unhappy to be dragged blinking out of the Thalia and shipped upstate. He talked fast, interrupted himself, and, finding few recent movies to praise, celebrated Max Ophuls and Jean Renoir. He delivered enigmatic observations like, “All movies should probably be in color.”

At evening’s end, I knew which camp I belonged in. I got an appropriately nerdy autograph for my Film Culture issue: “Cinecerely yours, Andrew Sarris.” More important, I exulted in a sense that my almost grim obsession with movies had been validated. Not for some time would I realize that I had enlisted, to put it melodramatically, in a fight for American film culture. The battle lines were drawn more sharply in Manhattan than in Albany, but everywhere one thing was clear. Kael was clearly the standard bearer for them, and Sarris was ours.

Obligatory comparison: S vs. K

Who were the them? They were the hip intellectuals who enjoyed a night at the movies. At faculty parties throughout the 1970s I had to check myself when professors of lit or law asked me if I didn’t find Kael’s review that week intoxicating. And she writes so well! As chief New Yorker critic, Kael became the grand tastemaker, a person even filmmakers courted. But who would try to curry favor with the guy who wrote for the Village Voice? It reminds you of the joke about the starlet so dumb she slept with the screenwriter.

Of course like all acolytes we overplayed the differences. Both Kael and Sarris loved classic studio cinema, the performers and scripts as much as the directorial handling. Both critics bemoaned Soviet montage and what they saw as its descendant, the overbusy technique of the 1960s. Both deplored stylistic aggressiveness (the Tony Richardson Syndrome) and both idolized Renoir. Both loved lyricism.

According to us, though, Kael wrote for those who dug movies, while Sarris wrote for those who loved cinema—the medium itself, or rather an exalted idea of the medium’s potential, an ideal form of expression at once dramatic, poetic, pictorial, and musical. He saw each film as bearing witness to the promise of what cinema might be, and he looked in even the tawdriest products for something approximating his dreams. Despite his enthusiasms, he tried for detachment, viewing the latest movie from some unpredictable historical perspective.

Kael famously declared that she watched a new film only once, because that was the way her readers would consume it. But who, we thought, would want to write about a movie after seeing it only once? Mightn’t it reveal some strengths or weaknesses on a second viewing? If it was a good movie, who wouldn’t want to see it more than once? In that same freshman semester, when there were still first-run double features, I sat through The Glory Guys twice in order to watch Help! three times. And that wasn’t even a particularly good movie.

Kael pounced on faults, Sarris savored beauties. Kael made each weak film seem like a blow to her intelligence. Sarris, although he could be harsh, tended to forgive. He taught that it was better to leave a door open than to write someone off—even Bergman, whom some of us would never learn to like until Persona, some not until Fanny and Alexander. Sarris subordinated his personality to that of the movie and its director, which made him seem less fiery than his uptown counterpart; but his attitude suited our own somewhat adolescent amorphousness of character. The arrogant certainty of our tastes was, paradoxically, born of a passionate humility, a sense of serving wise masters named Dreyer, Murnau, Mizoguchi.

Rethinking film history

Sarris is known primarily as the man who gave us the American version of auteurism, or what he called “the auteur theory.” It wasn’t a theory of cinema as such, but rather a heuristic approach to criticism: tips on what to think about and look for when you wanted to plumb a movie’s artistry. But initially, auteurism claimed to be a theory of something else. The opening chapter of The American Cinema is called “Toward a Theory of Film History.”

In Sarris’s day, most people writing about the history of film as an art accepted a notion of technical progress. According to this view, filmmakers became significant by contributing toward the development of the medium. Editing emerged through the efforts of Méliès, Porter, and Griffith, followed by the Russian Montage directors. Various national schools revealed more possibilities of the medium: fantasy and abstraction with the German Expressionists, derangement of sense with the Surrealists.

When sound arrived, a few directors (Clair, Mamoulian, Hitchcock) explored the stylized possibilities of that new technology. But many historians, considering that cinema was inherently a visual medium, declared sound an unwanted intrusion. Clearly, the great days of cinematic artistry were over. Most synoptic histories of the period fell silent about the evolution of technique after the 1920s and concentrate on the emergence of certain genres, such as the musical and the film of social comment.

Even André Bazin could be said to accept the premises of step-by-step artistic progress. Bazin showed that sound cinema wasn’t a dead end, that new artistic possibilities were exploited in the 1930s and 1940s. These were mostly creative alternatives to editing-based technique: the long take, extended camera movement, deep-space staging, and deep-focus cinematography. Bazin claimed that these techniques were most fully on display in the works of Renoir, Wyler, Welles, and some Neorealists.

Sarris was deeply influenced by Bazin’s ideas, but he didn’t accept the conception of film history as an accumulated technical evolution. Sarris called this the “pyramid fallacy,” with each filmmaker adding his slab to the rising and narrowing edifice of cinema. Instead, he proposed thinking of film history as an inverted pyramid, “opening outward to accommodate the unpredictable range and diversity of individual directors.”

In practice this demands that the historian survey entire careers, especially the works of ripe old age. It demands that the historian plot directors’ creative trajectories as paralleling and intersecting and overlapping—perhaps coalescing into broader trends, perhaps creating dead ends. The cinematic universe expands with each new film made, every old film rediscovered or simply re-seen. Auteurism “places a premium on having seen every work by a director who is deemed worthy of a study in depth; and by the time all the cross-references have been pursued in every possible direction auteurism seems to insist that every film ever made is relevant to the inquiry.”

Film history becomes less a linear progress toward something than a vast network of affinities and differences. This idea naturally led Sarris the writer not to the mammoth survey but to multifaceted essay collections. His big book, “You Ain’t Heard Nothin’ Yet,” looks like a panoramic history but is in fact a free-range miscellany, a sort of unbuttoned late-career redo of that Film Culture issue..

You can argue that Sarris was proposing a non-historical history, one that dispenses with concepts of influence and cause and that pulverizes any coherent narrative. That seems to me a valid objection. Despite its claim to be a theory of film history, Sarris’s auteurism strikes me as a historically informed approach to film criticism. The ultimate aim isn’t a convincing historical narrative but a compelling aesthetic judgment. Sarris’s idea of expanding filiation, infinite comparison and contrast, allows him to pursue what matters: evaluation.

In this respect at least, he’s agreeing with his predecessors, the writers who saw history as linear progress. But his criteria of value are different. For the traditionalists, the filmmakers who grasped the next step that the medium should take in its creative development become the best. For Sarris, the best filmmakers used the resources at their disposal to create valuable works that also displayed a distinct conception of human life. “Griffith, Murnau, and Eisenstein had different visions of the world, and their technical ‘contributions’ can never be divorced from their personalities.” Innovation was secondary to expression, and expression could best be gauged by tracking the wayward currents of the history of film style.

Auteur, yes; but of what?

New York Film Festival 1966: Pier Paolo Pasolini, translator, Andrew Sarris, and Agnes Varda. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

The auteur “theory” creates a decentralized and dispersed conception of film history—not a tree with a solid trunk and clear-cut branches but a bristling, tangled bush. The historian will dissolve big changes and broad trends into the doings of particular film artists. Who are these artists? Well, obviously, directors.

This move shouldn’t have been controversial. Critics had long assigned primary creative responsibility to directors. In the 1910s Louis Delluc heaped praise on DeMille and Sjöström, while Griffith was acknowledged around the world as a great innovator. Later von Stroheim, von Sternberg, Eisenstein, Pabst, Clair, Welles, Hitchcock, Maya Deren, and many other filmmakers were recognized as the artistic authority behind their work. In the early 1950s, foreign-language filmmakers such as Kurosawa and Bergman were identified (and even promoted by their distributors) as all-powerful creators saying something through their art.

Sarris’s real innovation was, along with the critics around Cahiers du cinéma and Movie, to transfer the idea of the expressive film artist from the headier regions of art cinema to the jostling, compromised world of Hollywood. There were obvious objections.

*Filmmaking is a “collaborative” activity, so you can’t attribute the final work to a single hand.

Yet in the collaborative medium of opera we speak of a Zeffirelli production as opposed to a Peter Sellars one. Why can’t a film director be a synthesizing artist orchestrating the contributions of many other artists?

*But in opera and other theatre forms, you have a preexisting text, the script or libretto or score. Why isn’t the screenwriter the artist, as Shakespeare or Verdi is?

Because theatrical texts are designed to be instantiated on different occasions, while film scripts are written to be produced only once. The film’s final form includes elements of the script, but that final form, being cinematic, can’t be uniquely specified in verbal language. As we all realize, give the same screenplay to six filmmakers, and you get six different and equally free-standing films.

*Popular film can’t be compared to high art. Artistry demands control, and the novelist, the painter, and even the opera director will exercise complete control over the final work. A Bergman or Antonioni has the cultural clout to dictate every aesthetic effect, but the Hollywood filmmaker works as part of a larger process controlled by others. He is handed a script and shoots it, and not necessarily all of it; second-unit and visual effects staff have their input too. The producer may demand more close-ups. In the classic studio system, the director wouldn’t typically get final cut; the producer would shape the released film. All these conditions constitute barriers to artistic expression. The auteur theory, when applied to Hollywood, is deeply inappropriate.

One answer to this objection is that many directors, including some of the best ones, did have a good deal of control over their work: Hitchcock, Hawks, and others were their own producers and worked on their scripts and oversaw their post-production. Moreover, a director can control choices down the line in sneaky ways, as when Ford shot his films so that they could be assembled in only one way.

Sarris advanced another reply to the control objection. If it owed something to the Cahiers young critics, he articulated and practiced it more keenly than they. He proposed a critical method: Take as many films signed by the director as you can find. Attend to the way they exercise their craft, the way they tell their stories and convey their meanings. Seek out an expressive core that seems distinctive, even unique.

Most directors’ collected works won’t yield this. “Not all directors are auteurs. Indeed, most directors are virtually anonymous.” Only the best directors will display a distinct expressive quality. Hawks and Hitchcock evoke radically different worlds of action and feeling, just as Mozart and Rembrandt can.

Fifteen years after his initial statement on the matter, “Notes on the Auteur Theory in 1962,” Sarris suggested that the elusive concept of personality was not to be derived from the director’s biography. “I was never all that interested in the clinical ‘personalities’ of directors. . . . A director’s formal utterances (his films) tell us more about his artistic personality than do his informal utterances (his conversation).”

For example, we understand John Ford’s respect for what Sarris calls “codes of conduct” not through the old curmudgeon’s interviews but by confronting the tangible texture of the movies. One of Sarris’s favorite examples occurs in The Searchers. Drinking his coffee, the Ward Bond character glances toward the wife of the household. Then his point of view reveals her stroking the uniform of her husband’s brother, played by John Wayne.

Cut back to Bond as the wife and her brother-in-law meet for a tender farewell. Bond stares off into space, chewing.

“Nothing on earth,” writes Sarris, “would ever force this man to reveal what he had seen. There is a deep, subtle chivalry at work here, and in most of Ford’s films, but it is never obtrusive enough to interfere with the flow of the narrative.” The economy is part of the point. “If it had taken him any longer than three shots and a few seconds to establish this insight into the Bond character, the point would not be worth making.”

In the Hollywood studio context, there was something heroic about the rare director who could surmount all the pressures, filter out all the noise, and shape the impact of his work. “The auteur theory values the personality of the director precisely because of the barriers to its expression.” Like a great Renaissance painter paid by a pope or a duke and pledged to illustrate well-known stories, the Hollywood director working for a studio could occasionally conjure up something powerful and distinctive.

Auteurism, Sarris claimed, is our straightest road to determining a film’s value. The great films, by and large, will be those that evoke distinctive directorial sensibilities. But “by and large” allows for the possibility of excellent movies that we can attribute to other forces—script, stars, source material, the happy intersection of talents. Casablanca, writes Sarris, “is the most decisive exception to the auteur theory.” Sarris loved movies more than he loved his theories.

Compare, contrast, repeat

Sarris’s breakthrough essay, “Citizen Kane: The American Baroque,” appeared in Film Culture during the 1956 revivals of the film. This detailed explication, published when Sarris was twenty-eight, betrays his grad-school training at a period when the New Criticism reigned. In a single stroke, he pioneered the sort of close reading that would become central to Anglo-American academic film criticism.

I can’t recall any later Sarris essay offering such an intensive analysis of a single film. As he developed his historically-guided critical appraisals, he favored synoptic appreciations of directorial careers. These became the occasions for him to point out interacting directorial personalities that comprise that vast network of cinema.

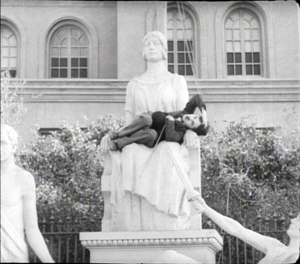

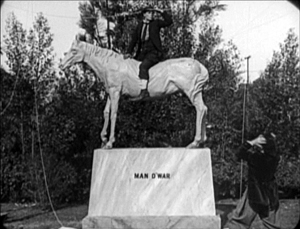

Instead of macro-analysis, Sarris embraced a strategy of “drilling down,” we’d now say, to a single revelatory passage. The chief tactic is comparison, often involving two directors faced with a comparable situation. Both City Lights and The Goat show a protagonist hiding on a statue about to be unveiled. Chaplin seizes the chance to deflate the ceremony.

But Keaton, says Sarris, is less interested in satire; he is “a pessimist in perpetual motion.” In The Goat, “Keaton remains mounted on the clay horse until it begins to sag and crumple under his weight, and the sculptor, a bearded nincompoop in a beret, proceeds to break down and weep.”

“Keaton’s expression here,” Sarris claims, “is mercilessly pragmatic. What good is a clay horse (art?) if you can’t mount it to your own advantage? There is something unabashedly ruthless about Keaton’s comedy, which chills his humor.” This was the period when critics, having just rediscovered Keaton’s films, claimed him as a “metaphysician.” Sarris likened him to Beckett.

Sarris wasn’t alone in turning to detailed commentary at the period; we had Dwight Macdonald’s appreciative 1964 essay on 8 ½ and John Simon’s book-length study of Bergman (1973). But Sarris got there early with the Kane piece, and throughout his career he used analysis to pinpoint authorial personality. Attention to nuanced differences allowed him to create a kind of connoisseurship.

The ultimate expression of this connoisseurship emerges in his concern for privileged moments. A critic has to be alert for shots or gestures or lines of dialogue that encapsulate the emotional tenor of a film and a director’s sensibility. Sarris’ example is a moment in La règle du jeu:

Renoir gallops up the stairs, stops in hoplike uncertainty when his name is called by a coquettish maid, and then, with marvelous post-reflex continuity, resumes his bearishly shambling journey to the heroine’s boudoir.

If I could describe the musical grace note of that momentary suspension, and I can’t, I might be able to provide a more precise definition of the auteur theory. As it is, all I can do is point at the specific beauties of interior meaning on the screen and later catalogue the moments of recognition.

No director but Renoir, Sarris suggests, would have Octave break the scene’s rhythm in exactly this way–and in a manner, Sarris’s bear-metaphor hints, that anticipates Octave’s costume for the climactic party in the chateau. The nonchalant, slightly awkward interruption epitomizes Renoir’s entire style of filmmaking, which has room for casual deflections from neat plotting and groomed performances. The critic’s words can’t wholly capture the force of Octave’s hop, and its resonance for Renoir’s film and his oeuvre. It is, says Sarris, “imbedded in the stuff of cinema.”

Both cinephiles and ordinary viewers are seized by luminous instants that change our skin temperature. We come out of a film satisfied if a few epiphanies have flashed upon us. The critic can signal them but not explain them fully. Interior meaning is the product of craft and personality, but it can’t be reduced to them. It creates a tingling, fugitive beauty that is unique to cinema.

Everyone has his or her own Sarris. The foregoing offers merely bits of mine, and they’re largely academic in slant. That’s because I think that Sarris changed, among other things, the way film history and criticism were taught in American universities. While Kael influenced film journalism, particularly in the upscale markets, Sarris’s legacy is best seen in cinephile criticism (Film Comment, Film Quarterly et al.) and academic film studies. Some Paulettes went to work for the New York cultural weeklies, high and low. Many people who were Sarrisites to some degree (Jeanine Basinger, James Naremore, John Belton, William Paul, Elisabeth Weis, Chuck Wolfe, Mark Langer, Robert Lang, et al.) became professors. Kael’s followers turned out essays, but Sarrisites like Todd McCarthy and Joseph McBride wrote books based firmly in research. Sarris’s version of auteurism has been reworked, in plenty of intriguing ways, in directorial monographs from university presses. He once remarked ruefully that he was an academic among journalists and a journalist among academics, but he managed to bridge the gap adroitly.

Sarris was too far-out for the New Yorker in 1965, and probably for the New Yorker of today. But history, and not just the history of movies, was on his side.

Sarris’ life and death have called forth many eloquent tributes. Among the best are Kent Jones’ career overview, Richard Corliss’s moving memoir, and Jim Emerson’s calm discussion of the excesses of the Sarris vs. Kael dichotomy. See also Ben Kenigsberg’s memories of Sarris’s teaching style.

My quotations are taken from Film Culture no. 28 (Spring 1963), The American Cinema (Dutton, 1968), Confessions of a Cultist: On the Cinema, 1955/1969 (Simon and Schuster, 1971), The Primal Screen (Simon & Schuster, 1973), and The John Ford Movie Mystery (Secker & Warburg, 1976). Thanks also to email conversations with John Belton of Rutgers and Dennis Bingham of Indiana University.

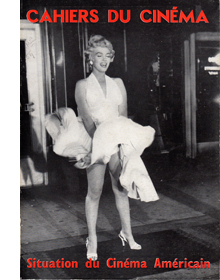

When I received Film Culture no. 28, I didn’t know that it represented a continuation of a Cahiers du cinéma tradition. In December 1955, the journal had published a special issue, “Situation du Cinéma Américain” (no. 54). It included not only critical essays but a “dictionary” of contemporary American directors: small-print filmographies followed by a paragraph of lapidary commentary. (“Lang’s work is founded on a metaphysics of architecture.”) Later issues devoted “dictionaries” to current French cinema (no. 71, May 1957), the Nouvelle Vague (no. 138, December 1962), and more recent American cinema (no. 150-151, December 1963-January 1964). In his American Cinema project, Sarris altered the format significantly by expanding the commentaries into essays and then grouping directors within sharp-edged, highly memorable categories of value. In turn, Sarris’s catalogue seems to have been the model for Martin Scorsese’s “Personal Journey through American Movies.” In the same tradition is Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage’s too-little-known American Directors (1983).

When I received Film Culture no. 28, I didn’t know that it represented a continuation of a Cahiers du cinéma tradition. In December 1955, the journal had published a special issue, “Situation du Cinéma Américain” (no. 54). It included not only critical essays but a “dictionary” of contemporary American directors: small-print filmographies followed by a paragraph of lapidary commentary. (“Lang’s work is founded on a metaphysics of architecture.”) Later issues devoted “dictionaries” to current French cinema (no. 71, May 1957), the Nouvelle Vague (no. 138, December 1962), and more recent American cinema (no. 150-151, December 1963-January 1964). In his American Cinema project, Sarris altered the format significantly by expanding the commentaries into essays and then grouping directors within sharp-edged, highly memorable categories of value. In turn, Sarris’s catalogue seems to have been the model for Martin Scorsese’s “Personal Journey through American Movies.” In the same tradition is Jean-Pierre Coursodon and Pierre Sauvage’s too-little-known American Directors (1983).

For more on C & C, which was a soda-pop company, go here. By 1956, WOR-TV was owned by the same company that owned RKO, so it’s no surprise that Kane, King Kong, and other items from the Movietime package played ceaselessly on that station. WOR’s radio station intersected my life from another angle.

For more on the standard version of the history of film art, along with Bazin’s revision of it, see my On the History of Film Style.

The homage volume, Citizen Sarris: American Film Critic, includes many fine pieces, but please don’t read my contribution. Editorial carelessness has mangled it beyond recognition. The version I’ll stand by, “Cinecerity,” is available in my Poetics of Cinema. Portions of this blog entry are lifted from that essay, but I’ve omitted most of my discussion of Sarris’s conception of film style.

New York Film Festival, 1966: Nat Hentoff, Pauline Kael, Parker Tyler, Arthur Knight, Judith Crist, Hollis Alpert, Andrew Sarris. Photo by Elliott Landy. From Film Culture no. 42 (Fall 1966).

PS 24 June 2012: More moving commentary in memoriam at the Film Comment site.