Archive for the 'People we like' Category

COGNITIVISTS STORM BIG APPLE! BIG APPLE ASKS, “WHAT’S A COGNITIVIST?”

The final SCSMI 2012 banquet, held on the tenth floor of the NYU Kimmel Center for University Life, Rosenthal Pavilion.

DB here:

Most years I offer an entry recording some events at the annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We did hold our conference–and a swell one it was, starting Wednesday at Sarah Lawrence College and wrapping up at the Cinema Studies department of New York University last Saturday. I heard many excellent papers and panel discussions. (The schedule is on a pdf here.) The event was also graced by keynote lectures by Alva Noë and Noël Carroll, and a night of splendid, eye-warping films by Ken Jacobs, no stranger to this blog (here and here and here). Malcolm Turvey of Sarah Lawrence and Richard Allen of NYU did an excellent job of coordinating the SCSMI event.

But I can’t offer my usual conference roundup this time. Kristin and I just got back last night, and we have only three days in Madison before taking off for Il Cinema Ritrovato. In those three days we have a hell of a lot to do, including setting me up for Medicare (!), as I’ll turn 65 during our trip. But I did want to supplement a small runup piece to the conference a couple of weeks back.

A few days after that post, I received the most recent issue of Projections, a journal with which SCSMI is affiliated. It’s stuffed with worthwhile pieces: Gerald Sim’s overview of the digital revolution (if any) in cinematography; Barbara Flueckiger’s essay, “Aesthetics of Stereoscopic Cinema”; Mark J. P. Wolf’s study of imaginary worlds on film; and James E. Cutting, Kailin L. Brunick, and Jordan DeLong’s correction of one claim they made about shot lengths and film acts. (Kristin discusses their project in this entry from last year.)

A few days after that post, I received the most recent issue of Projections, a journal with which SCSMI is affiliated. It’s stuffed with worthwhile pieces: Gerald Sim’s overview of the digital revolution (if any) in cinematography; Barbara Flueckiger’s essay, “Aesthetics of Stereoscopic Cinema”; Mark J. P. Wolf’s study of imaginary worlds on film; and James E. Cutting, Kailin L. Brunick, and Jordan DeLong’s correction of one claim they made about shot lengths and film acts. (Kristin discusses their project in this entry from last year.)

As if all this weren’t enough, the issue includes a lively and probing roundtable on Continuity Editing, with a superb synoptic article by Tim Smith summing up his eye-tracking research. (His study of There Will Be Blood is our now-classic guest blog.) Tim’s article is an ideal introduction to his wide-ranging research program. Several other scholars comment on Tim’s “attentional theory of continuity editing”: Paul Messaris, Cynthia Freeland, Sheena Rogers, Malcolm Turvey, Greg Smith, and Daniel T. Levin and Alicia M. Hymel. Tim replies to their criticisms in a follow-up piece. This sort of dialogue occurs very rarely in film studies, and it’s to be applauded. I think such serious and courteous exchanges are the mark of a mature, or at least maturing, discipline.

You can learn more about Projections here and read a sample issue here. If your library doesn’t subscribe, maybe you can hint that it should. Although it’s hard to determine the image format of the swirling filmstrip on the cover (image ratio and perfs are puzzling), note that at least it is film.

I learned so much from this year’s get-together that you shouldn’t be surprised if pieces of it float into upcoming blog entries. And in 2013, there’s always Berlin.

From Sam Wass, Parag Mital, and Tim Smith’s paper, “Cutting through the blooming, buzzing confusion: Signal-to-noise ratios and comprehensibility in infant-directed screen media.”

In cognito (we trust)

From Calvin & Hobbes, 10 April 1994.

DB here:

Every year at about this time, I trumpet the upcoming convening of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. This year’s powwow is held at picturesque Sarah Lawrence College, under the auspices of Professor Malcolm Turvey, no stranger to this blog. The final day of it will take place at NYU’s Cinema Studies Department. I had to miss last year’s conference for health reasons, but I’ll be there this year with a paper on 1940s Hollywood narrative.

Some earlier blog entries sketch out my take on what’s interesting about the group’s work. You can find treatment of the 2008 Madison gathering here and here; the 2009 Copenhagen event here and here with an epilogue about Lars von Trier and Asta Nielsen; and afterthoughts on the 2010 Roanoke meeting here. Last year, because I couldn’t go, I offered a web essay, here. This discusses my current thinking about the cognitive research framework.

This year, although I’m going, I’m again offering a new web essay. It’s about how models of mind (Gestalt, psychoanalytic, cognitive, etc.) have shown up in film theory and criticism. The piece is organized chronologically, and it tries to tie ideas about the psychology of cinema to a history of filmmaking: the theories I discuss emerge as responses to changes in form, style, and theme. The essay will eventually be reprinted in Art Shimamura’s anthology, Psychocinematics: Exploring Cognition at the Movies, forthcoming from Oxford University Press. Art’s collection gathers many cutting-edge essays from SCSMI members.

A sideways note: I learned recently that my old book, Narration in the Fiction Film (1985), sold 470-some copies last year. That’s a lot for an old academic study, especially one with many used copies in circulation. I infer from this (good cognitivists make inferences) that some instructors are using it in courses. I’m grateful, naturally, but I want to signal that I’ve altered some of the views I expressed in that book. If a professor is using my book to exemplify the cognitive perspective on narrative, I’d urge him or her to consider as well the web essay I already mentioned, “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?” In addition, my most recent answers to questions about filmic storytelling, in which narration is treated as one aspect of a larger process, can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in the collection Poetics of Cinema. In other words: I hope I’ve learned something since 1985.

The week following the SCSMI gathering, UCLA is hosting Visual Narrative: An Interdisciplinary Workshop on 20-22 June. This very promising event hosts presentations and commentaries from linguists, philosophers, and a couple of SCSMI star psychologists. Dan Levin has already made appearances in this blog (notably here), and Tim Smith, Continuity Boy, has contributed our perennially popular guest entry, “Watching You Watch THERE WILL BE BLOOD.” The distinguished philosopher of art George Wilson, author of Narration in Light, will also be there. Thanks to Rory Kelly, one of the Workshop’s organizers, for tipping me off.

After SCSMI (from which, or about which, I hope to blog), we’re off to Bologna, so expect more of our usual reportage from Cinema Ritrovato, that frenzy of movies and movie lovers. Coming up next, though, there’s Bette Davis to reckon with.

Cognition is important, but so is perception, as every front-row sitter knows. From The Film Fan (1939, Warner Bros., Bob Clampett).

A man and his Focus

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

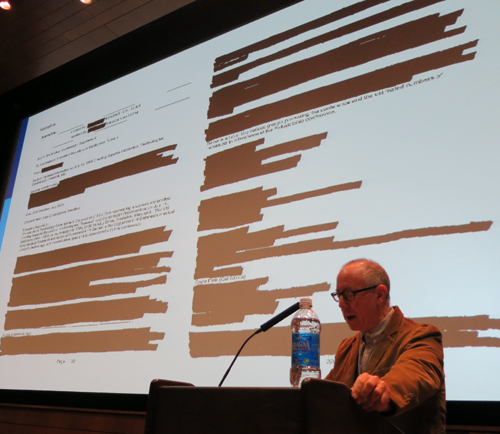

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.

Once more, Mad City movies

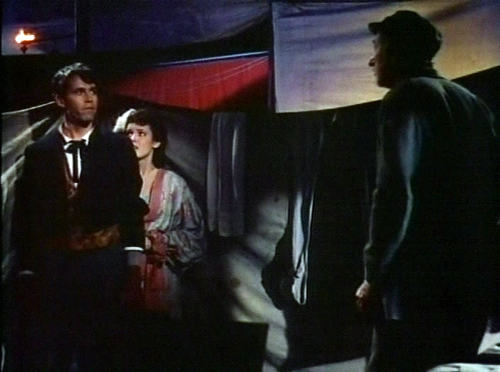

Night and the City.

DB here:

It’s been a busy time in Madison, at least for me. KT is in Egypt, peering at shards of statues and documenting earlier Armana excavations. I’m at home, having missed the Hong Kong International Film Festival (doctor’s orders) and wistfully wishing I’d been there for the tribute to Peter Chan Ho-sun (check out Fred Ambroisine’s interview at Twitchfilm) and a chance to see—Don’t say whoa!—Keanu Reeves, who was there with Side by Side, his new film on digital cinema (snif).

Instead of traveling, I’ve been doing other stuff. There were, and still are, last-minute checks and fixups on the new edition of Film Art. I went to some movies–Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace, The Hunger Games, The Raid: Redemption, Carnage, 21 Jump Street—as well as screenings at our Cinematheque. Late at night I’ve been watching 1940s films for a long-range project. Most frantically, I’ve been working on a little e-book to be finished, I hope, in three weeks. It will be available on this site, ludicrously cheap, you will want one for sure, I bet, well, why not? More about it later.

In the meantime, Madison has hosted some remarkable visits. I’ve already mentioned Lynda Barry’s delightful presentation of Chris Ware and Ivan Brunetti. I must also mention two other dignitaries that illuminated our lives this spring.

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

In early March, Tony Rayns (right), cinema’s man-about-Asia, came to pillage our city’s supply of DVDs and, not incidentally, give a lecture. It was his usual fine performance. “The Secret History of Chinese Cinema” took us through a series of unofficial classics stretching back to the 1930s, including Song at Midnight (1937), with its fairly off-putting defacement, and Scenes of City Life (1935), Tony’s candidate for the best unknown Chinese film. It was gratifying to hear him pay homage to Sun Yu, who attended UW’s theatre program long ago. Who knew that the great director of Daybreak (1933) and The Highway (1934) was a Badger?

More recently, we were visited by Schawn Belston, an old friend who’s Senior Vice-President of Library and Technical Services at Twentieth Century Fox. Our Cinematheque is running a string of Fox restorations, and Schawn brought along a stunning print of the lustrous noir classic Night and the City (Jules Dassin, 1950).

There’s a nifty story behind that print. Schawn and archivist (and Badger) Mike Pogorzelski discovered an original camera negative in the Movietone News vault in Ogdensburg, Utah. When they struck our print (directly from the neg) and showed it to Dassin a few years ago, he wept with pleasure.

Schawn found another version of unknown provenance. On the basis of the first reel, which he screened for us, this seems to be a British version, with a different voice-over narrator, varying footage and cutting patterns, and a lighter, more romantic score. As Schawn pointed out, this plays more slowly and is more of a melodrama than a thriller; it also makes the Richard Widmark character a little more sympathetic, I thought. Nobody has yet discovered why this version was made.

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

So a mood-drenched noir print, a new slant on postwar film, and a nice little puzzle. On top of those, a talk on the previous day by Schawn, discussing current restoration issues. Naturally the topic turned to the digital conversion, a hot topic on this site and elsewhere. Some basic facts from the inside:

*Lots of filmmakers are still finishing on film, but the plan is to make no prints available to US theatres after 2012. About 300 prints of current titles will still be made for the world market.

*Both Fuji and Kodak are still making film stock, even new emulsions, but the decline in usage will raise prices. A 35mm print now costs $4000, a 70mm print runs $35,000 and up.

*Storage problems are immense. The studio wants to save all the raw footage; in the case of Titanic, that comes to 2.5 million feet. Which version of the film has priority for the shelf? Typically, the longest cut, often the first preview print.

*All studios are still making 35mm negatives for preservation, typically from 4K scans. Ironically, their soundtracks, usually magnetic, can’t match the uncompressed sound of the files on a Digital Cinema Package (DCP).

*”Film is the most stable medium, but the preservation practices for it are the most vulnerable.”

*Nearly all film restoration is digital now, so the best way to show the results is probably digitally. That also makes for standardized presentation and less wear and tear on physical copies.

*Most classic films in a studio library are not available on DCP. If an archive or cinematheque or theatre wants one, there are ways to make on-demand DCPs. But it’s not cheap. A 2K scan runs $40,000; a 4K scan, somewhat more. Schawn opts for 4K because a digital version should be the best possible. It might be the last chance to make one!

*Films stored on digital files must be migrated frequently. Sometimes that’s done through “robotic tape recycling.” But there are problems with the constantly changing formats and standards. The Movietone News library was originally digitized to ID-1, a high-end broadcast tape format from the mid-1990s, so that material will need to be copied to something more current.

*Schawn believes that objective criteria about color, contrast, and other properties need to be balanced with concern for the audience’s experience. By today’s standards, original copies of Gone with the Wind and The Gang’s All Here look surprisingly muted. But to audiences of the time, they probably looked splashy, because viewers saw so few color movies. Restorers and modern viewers have to recognize that perception of a film’s look is comparative, and the terms of the comparison can change.

Schawn’s point was made after his visit with our Cinematheque show of the restored copy of Chad Hanna (Henry King, 1940). For a Technicolor film, it had a surprising amount of solid black, and not just in night scenes. We’re used to “seeing into the dark” via today’s film stocks and digital video formats, and we probably identify Technicolor with the candy-box palette of MGM musicals on DVD. We sometimes forget that chiaroscuro was no less a resource of color film of the 1940s than of black-and-white shooting of the period. A leisurely, charmingly unfocused story with a radiant Linda Darnell (she lights up the dark) and Fonda at his most homespun, Chad Hanna was good in itself and an education in color style circa 1940.

Schawn’s visit, like Tony’s, was informative and plenty of fun. We want to see both again soon.

Up next, as Robert Osborne would say: Some picks for the Wisconsin Film Festival, which launches Wednesday.

Thanks to Jim Healy, Cinematheque programmer, for arranging Schawn’s visit and the Fox retrospective.

Chad Hanna. Not, emphatically not, from 35mm; from Fox Movie Channel.