Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Merrily he rolls along: A belated birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim

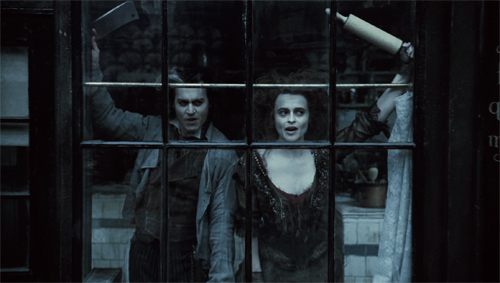

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Tim Burton, 2007).

DB here:

Last month Stephen Sondheim celebrated his ninety-first birthday. By coincidence, I just finished a section on him in my current book on popular storytelling.

The argument there is that art at all levels, high and low, mass and elite, depends on novelty. That demanded accelerated in the twentieth century, with the explosion of book publishing, magazines, film, radio, theatre, and television. I see this process as a vast energy of crossover. Popular and “middlebrow” storytelling picked up on avant-garde innovations. But it seems to me that modernism, even the High Modernism of Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner borrow more than is usually noted from conventions of popular storytelling. I hazard the view that it’s enlightening to look at how experimentation, innovations that open new avenues of artistic expression, emerge in mass-audience art.

Nowadays, most intellectuals have found something to love in mass culture. (“We are all nerds now.”) It wasn’t always so. In England and America, the “battle of the brows” had as one consequence the idea that true art, usually typified by High Modernism or the more radical avant-garde, was being squeezed. On one side was mass culture, manufactured as a commodity designed to sooth the masses. On the other was “middlebrow” art, which mimicked the techniques of modernism but made them simple enough for suburbanites to follow. By the 1960s, the people who believed in this trinity were in the minority, partly because they began to realize that centering on the most difficult side of modernism created too austere a prototype of all ambitious art. Irving Howe called this “The Decline of the New.”

Not that everything is a mashup. But I think now we all realize that crossover is a valid expressive option, probably the most pervasive one. The mass media make room for a huge amount of creativity that can’t simply be dismissed as lowbrow or middlebrow. And one reason it can’t is because we can still be excited by unexpected innovations.

Hence the importance of the nearly seventy-year career of a man who confessed a “taste for experiment in the commercial theatre.”

Experiments that are fun

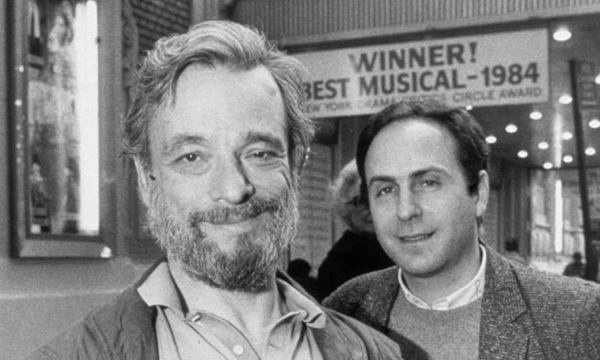

Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein.

You couldn’t, I think, find a better case for the prospects for experiment in popular culture than his work. His fondness for stage games is part of a theatre tradition we might call “light modernism,” a merging of avant-garde strategies with traditions of popular entertainment. It stretches back to Cocteau’s Parade (1917) and includes the work of Pirandello. Similarly, a trend in British theatre fused aspects of modern theatre (Pinter, Beckett, Ionesco) with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse and The Goon Show. Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) showed that what was “offstage” in one story could constitute the amusingly doom-laden plot of another.

Alan Ayckbourn dedicated his career to formal experimentation with space (three bedrooms as one in Bedroom Farce, 1975) and time (simultaneous action in How the Other Half Loves, 1969). Intimate Exchanges (1983) spreads forking-path plots across eight separate plays and sixteen possible endings. (Two of the variants are on display in Resnais’ films Smoking/ No Smoking of 1993.) House and Garden (1999) consists of two plays performed simultaneously in two auditoriums, with actors dashing between them. Ayckbourn’s most famous cycle, The Norman Conquests (1973) displays a “stacked” structure; each play gathers all the action taking place in one location and skips over scenes elsewhere, which are assembled in the other plays. The audience must construct the overall story, remembering what has happened just before the scene we see now.

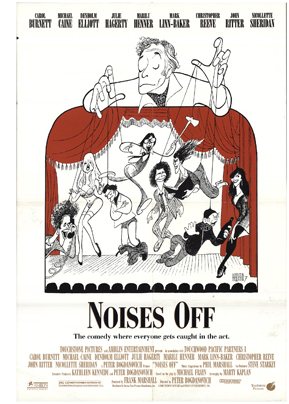

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Mystery plots make useful targets for this sort of popular experiment. Ayckbourn plotted some plays as quasi-thrillers, and Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1968) is a parody of the country-house murder. Stoppard undercuts the mystery by a Pirandellian device: two critics down in front are commenting as the performance unfolds. This gives Stoppard a chance to mock pretentious reviewing language. The standard whodunit device of reenacting the murder transforms into a replay of the opening act, but now with the critics taking the roles of detective and victim.

Also not surprisingly, both Ayckbourn and Stoppard declared themselves influenced by cinema, a reliable marker of crossover in modern media. Ayckbourn plays were adapted, with ingratiating wit, to film, while Stoppard wrote several scripts, most famously Shakespeare in Love (1998), which if the term means anything must count as defiantly middlebrow entertainment.

Sondheim is on the same frequency as these masters, but has, I think, greater bandwidth. He plunged into cinephilia more deeply. His early musical influences were Hollywood scores, notably that for Hangover Square (1945); Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979) was his tribute to Bernard Herrmann. A Little Night Music (1973) and Passion (1994) were adapted from films. Many of his songs refer to movies, and he composed music for Stavisky (1974), Dick Tracy (1990), and other projects. He was even a clapper boy for John Huston on Beat the Devil (1953).

Instead of parodying mysteries, he has been deeply committed to them. Detective fiction is his favorite reading, and as a puzzle addict he has spent hours devising murder games. “I have always taken murder mysteries rather seriously.” Both Company (1970) and Follies (1971) were initially planned as mysteries, with the latter concerned not with “whodunit?” but “who’ll do it?” Sweeney Todd is a paradigmatic revenge thriller. Asked by Herbert Ross to write a film, Sondheim and Anthony Perkins (another admirer of “the trick kind” of mystery practiced by John Dickson Carr) came up with The Last of Sheila (1973).With George Furth, Sondheim wrote a play, Getting Away with Murder (1996), and with Perkins he planned the unproduced Chorus Girl Murder Case, an homage to 1940s Bob Hope movies. The clues would be hidden in the songs.

Fiddling with formula

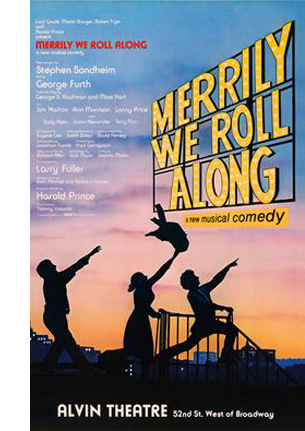

Sondheim and producer/director Hal Prince (left) during rehearsals for Merrily We Roll Along.

Sondheim’s zest for film and mystery fiction reflects a deep admiration for popular culture. It’s one thing to enjoy it, as Ayckbourn and Stoppard clearly do, while also poking fun at its silly side. It’s something else to appreciate its artistry in depth and try to master the conventions yourself. Despite learning “tautness” from the austere avant-gardist Milton Babbitt, Sondheim took as his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II. Tin Pan Alley, with its finger-snap rhythms and suave wordplay, pushed him toward a brisk cleverness. The virtuoso rhymes in his bouncy “Comedy Tonight” (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1962) inevitably bring a grin: Panderers! Philanderers! Cupidity! Timidity! . . . Tumblers, grumblers, bumblers, fumblers!

While executing these pirouettes, the song provides a Cliffs Notes guide to Roman New Comedy by contrasting it with tragedy. Tonight, weighty affairs will just have to wait. Sondheim similarly lays bare a convention in his script for the unproduced movie Singing Out Loud, where the couple gradually learn that it’s okay to express emotion in song. “They have to learn to overcome the unreality of it and break into song in the conventional manner of all musicals.”

By taking fun seriously, Sondheim ransacks culture high and low for occasions for experimentation. He was crucially influenced by Allegro (1947), an ambitious Rodgers and Hammerstein musical he considered “startlingly experimental in form and style.” Its use of sliding screens to create “cinematic staging” would become standard in later musicals. He calls Hammerstein “the great experimenter” who used the verse sections of songs to explore possibilities of structure, melody, and harmony.

Sondhim’s breakthrough experiment was Company (1970). It consists of flashbacks framed by the protagonist Robert’s thirty-fifth birthday party. Sondheim claimed it offered “a story without a plot.” The flashbacks don’t supply a goal-directed character arc and instead sample Robert’s bachelor lifestyle and its effects on his three girlfriends and the five married couples in his circle. The result is a compare-and-contrast pattern of parallels. Complicating things further, bits of action are accompanied by a chorus-like commentary from characters not in the scene. Still, there is a certain progression to the whole, indicated by Robert’s disillusioned but faintly hopeful final song, “Being Alive.”

The nonlinearity of Company poimts up Sondheim’s impulse to play with time, viewpoint, and other techniques. Assassins (1990) moves freely back and forth across a hundred years. In Follies characters argue with their former selves. Sunday in the Park with George (1984), built on parallels between two painters, assigns inner monologues to artist and model; characteristically, Sondheim expresses jumbled thoughts by avoiding rhymes. Another duplex structure (Before/ After) shapes Into the Woods (1987), s a virtuoso braiding of classic folktales into a single plot.

Several plays utilize a narrator, who may take a role or converse with the characters. The Narrator of Into the Woods is killed fairly early in the action. Alternatively, Sondheim conceived Passion as an epistolary musical. Characters writing or reading letters operate “somewhere between aria and recitative,” rendering the emotional climaxes as “read rather than acted.” In this excerpt, Giorgio goes to bed with Clara while Fosca is reading his letter breaking up with her. This is a concert performance; in a full production the couple undress on one side of the stage, while Fosca reads the letter. Time floats uncertainly

Working in musical theatre gave Sondheim a layer of implication beyond what Stoppard and Ayckbourn had available with spoken dialogue. A score can evoke earlier scenes through leitmotifs and can enhance characterization. Starting with Anyone Can Whistle (1964) Sondheim created pastiche songs that vary from the show’s overall style. Merrily We Roll Along incorporates cabaret acts (“Bobby and Jackie and Jack”) while Assassins integrates various popular musical traditions, from vaudeville to melodrama. We might think of these pastiches as akin to the “polystylism” of the chapters of Ulysses, which Sondheim strongly admires.

Pacific Overtures (1976), a chronicle of Japan’s early engagements with the west, has the structure of a “portmanteau” film composed of exemplary episodes. It too has a narrator, the Reciter, and its experiments include turning renga linked verse into a passed-along song. The most formally daring scene, “Someone in a Tree,” stages the March 1854 signing of the treaty opening up ports to American ships. We do not see the ceremony, which is held in a secure house.

The Reciter questions an old man who claims that as a boy he watched the negotiations from a tree. During their dialogue, a boy clambers up the tree, and he and his older self collaborate in reporting the event he sees but cannot hear. Then the Reciter discovers a samurai guard hiding beneath the floorboards. He reports what he hears but cannot see. (Beware the YouTube ad at the start.)

As the singers’ accounts intertwine, a moment is assembled through partial perceptions. In a gesture reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s novels, the event is broken up, made accessible only through partial viewpoints. And only the witnesses attest to the event; without them, we have no access to history. “I’m a fragment of the day./ If I weren’t, who’s to say/ Things would happen here the way/ That they’re happening?” In adapting novelistic techniques for relativistic point of view to the stage, Sondheim, as an experimental storyteller, is ready to plunder any tradition that can yield something fresh.

Form, “content,” and everything in between

Sondheim and collaborator James Lapine.

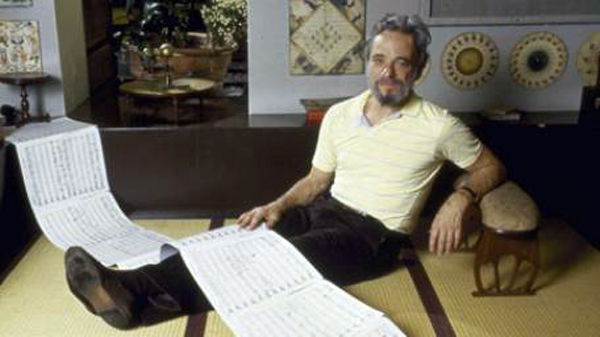

In his invaluable creative memoirs, Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011), Sondheim claims as a basic creative principle “Content dictates form.” But his puzzle-addict efforts to seek out difficulties to be overcome makes me think that this is more alibi than axiom.

I’d rather think that like many experimental artists, Sondheim uses “content” (whatever that is: subject matter, theme, bare-bones story) as at best one ingredient and often as a handy excuse. Sometimes audiences need help when faced with radical novelty. People may have been more receptive to Debussy’s daring pieces because of the “atmospheric” connotations of their titles. The stratagem of labeling one movement of “La Mer” as “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea” was pointed out by Erik Satie: “I liked the part at quarter to eleven best.”

Granted that Sondheim tries to suit his words and music to the genre and story he has selected, he often seems to take “content” as a pretext for solving problems he sets himself. Who else would decide to write all the songs for A Little Night Music in waltz tempo, not least for the challenge of avoiding monotony?

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

The purported rationale for telling their story backward is that it poignantly traces the loss of youthful idealism. But that arc could be just as poignant laid out in chronological order–or, if you want advance knowledge of how the struggles will turn out, via chronological flashbacks wrapped in a contemporary time frame. The reverse chronology seems both an experiment in whether audiences can follow the string of events and an effort to end a sad story in an upbeat way, with the characters still vigorous and hopeful–while we know what awaits them.

Sondheim faced an initial task of making the time scheme clear. He came up with transitional choral passages by the whole company that signal the shift to an earlier block of time. Different productions experimented with ways of reinforcing these musical tags, such as a synoptic slide show reminiscent of the “News on the March” sequence of Citizen Kane.

But the inverted chronology of Merrily We Roll Along also justifies experiments in musical texture. Because the play is about friendship, melodic motifs are swapped among the characters in their soliloquy songs. Moreover, in a 1-2-3 plot, Sondheim explains in Finishing the Hat, fully vocalized melodies are given reprises, shorter versions of the original number. Sondheim could have followed this convention. Instead, in relentless adherence to the reverse chronology, he made the reprises come first, as appetizers for songs yet to be fully heard. The puzzle addict will try to fit everything together in surprising ways, whether the audience realizes the fine points or not.

Solving one problem can launch a cascade of further problems. To introduce a 1980s audience to the musical ambience of Broadway’s heyday, Sondheim opted to revive the thirty-two bar song that he and his generation had “stretched out of recognition.” But then his penchant for pastiche posed a new problem. How to use that schmaltzy song form not just to satirize superficial characters like Joe the producer but to sustain connection to the sympathetic characters when they express authentic emotion?

Sometimes the problem is set not by “content” but by genre, tradition, or purely practical contingencies. Sondheim embraces show-biz conventions to discover what he can do with them. Hammerstein told him that the opening number can make or break a show, so Sondheim strives for a grabber when he can. The eleven o’clock number, a hangover from the days when shows began at eight-thirty, demands a show-stopping vehicle for the stars–e.g. “Anything You Can Do” in Annie, Get Your Gun. For Anyone Can Whistle, Sondheim wrote “There’s Always a Woman,” a rapid-fire comic confrontation between the two stars Angela Lansbury and Lee Remick, dressed identically. He conceived it as “the eleven o’clock number to end all eleven o’clock numbers.” It didn’t achieve what he wanted (“more like a ten-fifteen”) but it indicates his inclination to display virtuosity in response to purely formal demands.

Look, he made a show

Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat take us into the artisan’s kitchen–not only the studio or the stage where a team comes together but also the kitchen that’s the mind of the creator, who sweats out as much as possible beforehand. Sondheim shares with us the “choices, decisions and mistakes in every attempt to make something that wasn’t there before.”

This is a rarer accomplishment than you might think. Relatively few artists in any medium have the wish or ability to probe their creative process in detail, from conception to minutiae of execution. There are plenty of artists who talk of story sources and bursts of inspiration, but they seldom get down to the compromises, workarounds, and failed efforts. The best such books on popular storytelling, Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Patricia Highsmith’s Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, are illuminating, but nothing compared to the multilayered self-consciousness Sondheim brings to the task. He notes: “The explication of any craft, when articulated by an experienced practitioner, can be not only intriguing but also valuable.”

It helps when the artist works in brief, segmented forms, such as the songs that make up a musical. They can be analyzed line by line, and can illustrate the challenges of word choice, rhythm, and rhyme as they relate to the ongoing story, the portrayal of character, and of course the score. This engineering side of construction, basic to popular art, is attractive to a practitioner who happens to be a puzzle fiend. He makes every choice a challenge to his ingenuity.

Take one example, “A Little Priest” from Sweeney Todd. Sweeney has decided to turn his lust for personal vengeance into random barber-chair homicide. This scheme suits Mrs. Lovett’s need to produce better meat pies. The result is a list song, a Sondheim favorite. Here’s the rendition of the Broadway original with Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury, for most of us the definitive version.

The couple deliriously catalogue what citizens might furnish appropriate ingredients. Sondheim’s founding choice: the list will consist not of individuals, who would need naming, but of social types whose titles can rhyme more easily. Sweeney role-plays a customer checking Mrs. Lovett’s imaginary wares.

Todd: What is that?

Mrs. Lovett: It’s priest./ Have a little priest.

Todd: Is it really good?

Mrs, Lovett: Sir, it’s too good, at least./ Then again, they don’t commit sins of the flesh./ So it’s pretty fresh.

Todd: Awful lot of fat.

Mrs. Lovett: Only where it sat.

Todd: Haven’t you got poet/ Or something like that?

Mrs. Lovett: No, you see the trouble with poet/ Is how do you know it’s/ Deceased?/ Try the priest.

Second choice: the song must be constructed so that the rhyming emphasis falls on the types, so the lines end on the name of the profession, as above. Third choice, new constraint: Throughout the play, Sondheim tries for triple rhymes, so one- or two-syllable professions (priest, poet) will allow for that. Fourth choice: the need to build the song out of short lines, which will permit “an increasingly intricate rhyme scheme.” That’s on display here, with priest–least–deceased–priest threaded with flesh–fresh and fat–sat–that and poet–know it.

The song surveys a range of social types, while reminding us of Sweeney’s main target Judge Turpin (“I’ll come again/ When you have judge on the menu”). The climax of the song declares a perverse commitment to equity. “We’ll not discriminate great from small/ No, we’ll serve anyone/ Meaning anyone–/ And to anyone/ At all.” The catalogue culminates in a sprightly celebration of mass murder.

Finicky as ever, Sondheim confesses that he never liked the line “Meaning anyone,” which is a place-filler, but now he says he knows how to improve it.

Why probe the artist’s craft in such detail? Sondheim notes that journalistic reviewers aren’t trained in technique or don’t know the trade secrets; they’re just declaring what they like or dislike. More intellectual and academic critics are inclined to write broad overviews, usually about the cultural sources and effects of the music. A practitioner who explains the cascade of decisions, freely made or imposed from without, can provide something rare. Just as the sports fan enjoys learning the fine points, learning the tricks of the artist’s trade can boost our appreciation. We can learn to enjoy “the spectacle of skill.”

No surprise: I was reminded of the historical poetics of cinema. This approach to film studies tries to analyze how filmmakers draw on the menus of options normalized in particular times and places. In trying to discover principles of craft practice, we seek out any information we can glean from artisans. For this purpose, we’ll not discriminate great from small.

At the movies

Sondheim with Steven Spielberg on the set of the remake of West Side Story.

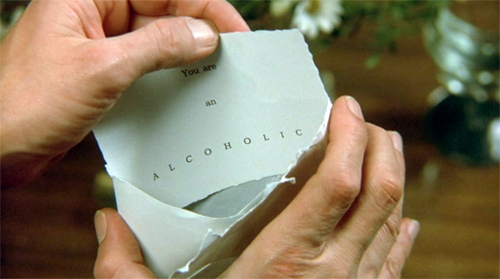

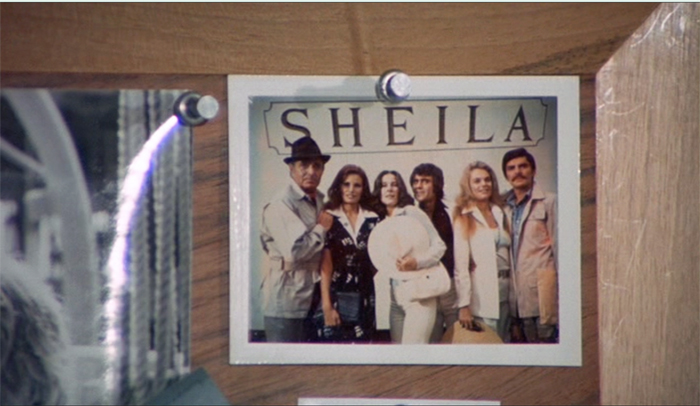

The Last of Sheila is a brittle, cynical satire on the film industry while being a well-designed classic mystery. Sheila Greene is struck down by a hit-and-run driver after she storms out of a party she and her husband Clinton have been holding. Under the promise of a potential movie deal, Clinton gathers six suspects on a pleasure cruise on the French Riviera. Once they’re are aboard, Clinton announces the entertainment: a mystery game. Each guest receives a card declaring a secret, such as “You are a homosexual” and “You are an alcoholic.” Clinton assures them that each is simply “a pretend piece of gossip,” but it becomes clear that the game is designed to expose someone, not necessarily the recipient, as guilty of the card’s charge. Meanwhile, Clinton tries to discover Sheila’s killer.

Every night, at the port they visit, the guests must follow clues to link one of them to a past transgression. The game is interrupted when one of the travelers is killed, and so the survivors embark on their own investigation. As in an Agatha Christie novel, the characters are stock types. There’s the vapid star, her hanger-on husband, the over-the-hill director, the rapacious talent agent, the second-tier screenwriter, and his heiress wife. Again, as in Christie novels like Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, the yacht cruise isolates the suspects and allows them to debate the identity of the culprit but also also to reveal Clinton’s scheme. In response, the killer has conceived a counterplot for baffling the other guests. Instead of these Christie novels, there is no designated Great Detective to take Hercule Poirot’s place. Any of the people hazarding solutions could be guilty.

In the spirit of the “fair play” detective novel, the audience is provided some clues that flit by, but can be checked on a replay. It’s not a spoiler to note the casual early appearance of an icepick, or the glimpses of some–but not all–of the clue cards.

By contrast, as John Dickson Carr points out, the really skillful mystery writer rubs your nose in the clues. It’s not a matter of a passing mention of the color of a man’s tie, or the way a character pronounced a word.

The masterpiece of detection is not constructed from “a” clue, or “a” circumstance. . . . It is not at all necessary to mislead the reader. Merely state your evidence, and the reader will mislead himself. Therefore, the craftsman will do more than mention his clues: he will stress them, dangle them like a watch in front of a baby, and turn them over lovingly in his hands.

The best example of this tactic in the film is the photograph at the bottom of this entry. The shot lets us dwell on Clinton’s apparently innocuous photo of his guests. Elsewhere the script plays up that old favorite, the discarded cigarette butt.

Sondheim and Perkins’ passion for classic detection is revealed in a long sequence of pure ratiocination. Across twenty-one minutes in the yacht’s lounge, one guest reconstructs the scenario behind Clinton’s game. The layout of space, in both long shots and shot/reverse shot, is quite precise and varied. Of course there are clues in the behavior of certain characters.

Part of the reconstruction turns out to be erroneous, as in the detective-novel convention positing an initial, faulty solution. In all, The Last of Sheila, while memorializing the sort of scavenger hunts and elaborate games Sondheim put his friends through, remains a rare example of an updating of the classic whodunit.

By contrast, the film adaptation of Sweeney Todd is a suspense thriller. The plot doesn’t hinge on an investigation but a pursuit (although that does yield a surprise revelation). Sondheim considers it the only satisfactory film version of one of his shows. “This is not the movie of a stage show. This is a movie based on a stage show.” But then what was the show? Opera? Operetta? No. “What Sweeney Todd really is is a movie for the stage.”

And a grim, brutal one at that. Tim Burton has developed Sondheim’s original through several cinematic strategies. One emphasizes Sweeney’s willed estrangement from humanity. If the stage Sweeney, often played by a large man, has a certain sweeping bravado, Sweeney on film scowls in soft-spoken fury. His puckered brows and pinched lips are set in a face as unearthly pale as a cadaver’s, or a clown’s. This seething little man is presented as virtually locked in his quarters, peering out at the world on which he will wreak vengeance.

Sweeney’s isolation is given a narcissistic cast when he unpacks his razors. He who has no human ties croons to “my faithful friends.”

Mrs. Lovett looks on, trying to secure a connection: “I’m your friend, too.” But he ignores her. Burton provides POV shots of Sweeney’s face reflected in his razor blade, a neat way of showing his self-absorption passing into violence.

At one point, he seems to register Mrs. Lovett’s gestures of affection, and Burton neatly shows the POV reflection shifting to her.

His contemplation of her as an ally can, it seems, only see her as another reflection of himself and an instrument of his vengeance–a tool, not a lover.

He rejects her affection (“Leave me”) and he twists the razor, turning the reflection back to him. He’s still locked in his solitary obsession.

He finishes the song alone, now even more committed to his mission. A final shot shows him gleefully peering out the window at the city he and his faithful friends will ravage.

Mrs. Lovett becomes his genuine accomplice in the song, “A Little Priest.” In the stage directions, Sondheim asks that Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett use pantomime to evoke the meat pies they want to harvest from Sweeney’s customers. In the film, however, the pies she has already made are surrogates for the ones she proposes.

Given the more tangible setting, Burton returns to the window motif; Mrs. Lovett’s shop becomes an extension of Sweeney’s enclosed world. The couple’s list-song takes place with the two of them at the windows, scanning the street for victims. As you’d expect, they spot a priest first.

If the barber shop upstairs is Sweeney’s mission control, the pie shop becomes his supply center. Mrs. Lovett realizes that she can get his friendship only by joining his plan for vengeance, and once he realizes her commitment, she becomes an attractive partner. They pledge their partnership in a rolling-pin waltz, and the sequence ends with a shot that echoes the earlier capstone, but including Mrs. Lovett.

There’s a lot more to be said about The Last of Sheila and Sweeney Todd, but I invoke them just to show that Sondheim’s talents can create robust, innovative, sometimes disturbing cinema.

I could imagine someone criticizing Sondheim as the ultimate middlebrow artist. Adapting foreign films (Smiles of a Summer Night, Scola’s Passion) and Grand Guignol to the American musical; turning Seurat’s Grande jatte into a living tableau (and naming the painter’s model Dot!); imposing games with time and viewpoint on a showgirls’ reunion; investing fairy-tale optimism with sinister implication–all can seem too clever by half. An objector might say that a Sondheim show doses schmaltz and hokum with just enough formal ingenuity to let audiences feel clever. But I think that sort of having-it-both-ways defines a great deal of popular entertainment, and it has its own value. Bergman and Seurat and Little Red Riding Hood remain unharmed by plays that take them as pretexts for ravishing music and cunning theatrical games. Formal ingenuity is not a small thing.

Sondheim opened new vistas for the musical to explore. I suppose you can call Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton middlebrow too, making rap and hip-hop safe for people who can afford a Broadway ticket. But if you think Miranda opened new paths, note that he thinks that Sondheim pointed the way. He took advice from Sondheim while writing the show, and he paid tribute in a preface to an interview:

He is musical theater’s greatest lyricist, full stop. The days of competition with other musical theater songwriters are done: We now talk about his work the way we talk about Shakespeare or Dickens or Picasso.

You don’t have to go that far to see that artists at all levels of taste innovate, and their efforts sometimes oblige us to see fresh expressive possibilities in their artforms. If we are all nerds now, we can become connoisseurs of the experimentation–sometimes subtle, sometimes bodacious–that pervades popular entertainment. Sondheim, meticulous and generous and tirelessly exploring, coaxes us to do that.

I’ve drawn most of my Sondheim quotations from Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes (Knopf, 2010) and Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011). Other remarks come from Craig Zadan, Sondheim & Company (Harper & Row, 1994) and Meryl Secrest, Stephen Sondheim (Knopf, 1998). Google Book Search should help you locate my citations by phrase. Steve Swayne provides a thorough analysis of the role of cinema in his career in How Sondheim Found His Sound (University of Michigan Press, 2005), 159-213.

More general books about the craft traditions Sondheim adopts and revises are Philip Furia’s The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists (Oxford, 1992) and Jack Viertel, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2016. I’ve praised and applied Viertel’s account in this earlier entry.

Sondheim discusses the composition of “Someone in a Tree” in this interview with Frank Rich. The second part is especially revealing about Sondheim’s combining music and lyrics through a vamping figure. That accompaniment, detached from the sung melodies, depends on a “gradual change” principle that reminds me of the minimalist music of Glass (Einstein on the Beach, 1975) and Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, 1976) at the same period. A musicologist would probably correct me, but if the affinity holds good it would further show Sondheim’s pluralistic appropriation of many traditions. Thanks to Jeff Smith for discussions of this and for help with other musical matters.

The John Dickson Carr quotation comes from his 1946 essay, “The Grandest Game in the World.” The most complete version of it is in The Door to Doom and Other Detections, ed. Douglas G. Greene (Harper, 1980), 334-335.

Many fine appreciations of Sondheim appeared around his birthday, but I especially like this one by Jennie Singer, packed with clips.

For a long time Kristin and I have studied innovations in popular storytelling, as in her analysis of narrative in the New Hollywood, my book on the same area, her monograph on P. G. Wodehouse, our book on Christopher Nolan, my studies of Hong Kong cinema and 1940s Hollywood, and comments over the years on this blog (e.g., Paranormal Activity and Happy Death Day). For more on Into the Woods, go here.

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973). This shot harbors a clue–actually, more than one.

P. S. 18 April 2021: Sondheim has been extraordinarily generous in sitting for interviews describing his creative process, and many are stimulating. Alert reader and master interviewer Brian Rose kindly sent me a link to the remarkable 2020 interview with Adam Guettel that you might enjoy.

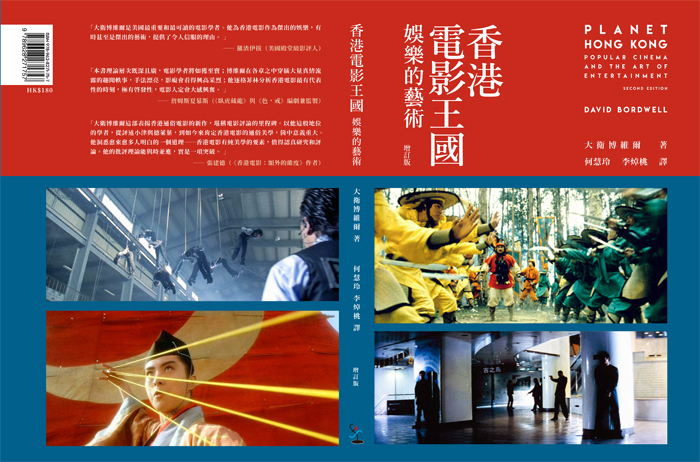

PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

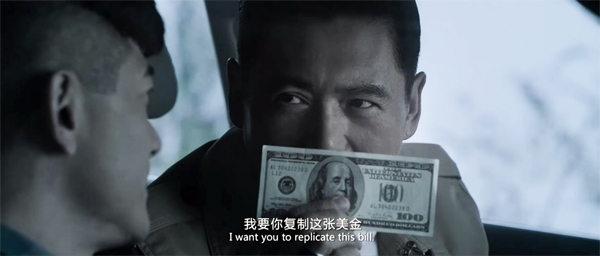

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.

One thousand entries and still hanging on

Venice International Film Festival screening 2017 of Rosita, in the Sala Darsena. Pre-coronovirus, no social distancing.

Both of us here:

Kristin:

This, our 1000th entry in this blog, comes at a strange point in our lives, and everyone else’s. Films, all facets of which are our main subject, are nearly gone from the big screens upon which we prefer to view them. Normally at this time we would be anticipating another trip to the Venice International Film Festival, which shows films in venues with very big screens and superb sound systems. Now we’re streaming and watching discs on a medium-size TV.

Back when our first entry appeared, on September 26, 2006, we weren’t thinking about whether we would ever get this far. We didn’t really know what the blog would contain. We hadn’t even come up on our own with the idea of starting it. One of the users of our textbook, Film Art: An Introduction, suggested it.

Back in those days, textbooks were simple things. They were physical, without digital iterations. They might have a handful of online resources, and perhaps teachers could assemble their own custom text from parts of the book. As each revision rolled around, McGraw-Hill invited around a dozen users of the book to fill out a detailed questionnaire, picking out its most useful parts and making suggestions for changes.

We occasionally found these comments helpful, but most of them involved adding more material. We weren’t allowed any additional pages for new editions, so those suggestions, often reasonable, had to be ignored.

I remember vividly, however, one unique comment that ran something like this: “Why don’t the authors start a blog?” (The questionnaires were anonymous, but if you recognize yourself as the culprit, let us know and we’ll all share a virtual laugh.)

Naïve souls as we were, we thought this suggestion might be a good idea. We could provide little essays that complemented the textbook, expanding it, as it were, without extra pages. Of course, it would also publicize Film Art and its companion, Film History: An Introduction.

Starting the blog was relatively easy. David had already created a website (thanks to Jonathan Frome and Vera Crowell) that could host it. Later our long-time web tsarina Meg Hamel set up the blog, to which we could add posts and photos ourselves.

Widened horizons

In the first brief entry, of 26 September 2006, David wrote about Christine Vachon’s recently released book, A Killer Life: How an Independent Film Producer Survives Deals and Disasters in Hollywood and Beyond. The idea was that Vachon touched upon aspects of film form and style that were relevant to ideas we discussed in Chapters 1 t0 3 of our textbook. Soon, though, we departed from the idea of tailoring our content strictly to Film Art.

The next two entries (here and here), again by David, reported from the Vancouver International Film Festival. The timing was purely coincidental. Tony Rayns had invited him to be a judge for the Dragons and Tigers competition for young Asian filmmakers, and it was his first visit. So he was officially there as a guest, not a blogger, but those two entries were already more substantial than the opening one. And of course he was happy to see two old Madison friends, film programmer Alissa Simon and filmmaker, and former DB teaching assistant, James (Jim) Benning.

He followed those immediately with two reports (here and here) from the American Society for Aesthetics conference, which happened to take place in Milwaukee that year. And I followed that by tearing apart disagreeing with an article in the Wall Street Journal. Its author predicted the end of logical Hollywood plotting because one interactive movie had been released. Its title, “The end of cinema as we know it–yet again,” could have been used for quite a few pieces we have written over the years. These early entries, modest though they were, set a pattern for some of the motifs that have run through the blog ever since (at least, until the present crisis).

In short, we branched out in any direction that events or our fancies took us. David even did some non-film pieces, mostly about related arts and about current politics.

Some of our entries could be of use to teachers and students. Each year in advance of the start of the school year, I post an entry called “Is there a blog in this class?” (This year’s is coming up soon.) There I suggest, chapter by chapter, which entries are relevant to each. We also started putting call-outs to selected entries in the textbooks themselves. In the e-editions these are live links. We hope these are of use to the people who were the original putative targets of the blog.

After sixteen years, we have noticed how the blog has changed us as scholars and cinephiles. Mostly this has been for the better.

For one thing, publishing outside academic, peer-reviewed contexts has given us the freedom to write in a bit less formal prose. I had already adopted this approach for The Frodo Franchise: The Lord of the Rings and Modern Hollywood, in which I tried to balance research with a more casual style that could appeal to fans of Peter Jackson’s adaptation. (That book had recently gone to into press when we started the blog.) David’s two most recent books and the one he is working on now reflect this change, and that has been commented on–mostly favorably.

Perhaps more importantly, the blog made us more visible in film circles outside of academia. After all, blogs are part of social media, albeit by now a rather old-fashioned element in that vast internet swirl. By flinging our stuff out into the ether, we had unwittingly ventured into journalism of a sort. We found ourselves able to get press accreditation to actual events out in the real world.

David’s visit to Vancouver in 2006 was not as a blogger, but over the years that followed, we remained welcome guests in part because we reported regularly on the films we saw. In advance of David’s retirement from university teaching in 2004, we had envisioned ourselves, among other things, having more time to attend festivals. This turned out to be feasible, as we added reports on Hong Kong (which David had already started attending), Il Cinema Ritrovato (Bologna), Cinédécouvertes (Brussels, sadly no longer held), Ebertfest, Palm Springs, Torino, and for the past three years, Venice, as well as our own Wisconsin Film Festival. On the right, you see Med Hondo, who visited Bologna in 2017.

The blog also led us in a modest way into the world of streaming. We have long had a friendly relationship with the dedicated team at The Criterion Collection. We’ve done supplements for them and with their cooperation used clips from their classic films in online educational materials for our textbooks. (The folks there view us as educating their future customers, and we hope that has been the case.) Whether they would have asked us and our collaborator Jeff Smith to contribute a series of video essays on the films streaming on The Criterion Channel is unclear, but we, and possibly they, thought of such a series as a sort of extension to the blog. Indeed, we gave it the same name, “Observations on Film Art.”

Entries in that series are more elaborate than blog entries, of course, and we feel it is something of an accomplishment to have reached thirty-seven to date, with more unedited material already “in the can.” It is a privilege to be involved, even in a small way, with what has quickly become the leading art-house/indie/classic film streaming service, and we suspect we owe that in part to the blog.

Film history passing before our eyes

Werner Herzog, Roger Ebert, and Paul Cox at Ebertfest 2007.

Our regular attendance at the festivals has been a huge boon in allowing us to keep up with many of the year’s new films on the big screen rather that waiting for the home-video release or, more recently, streaming availability. Lately we have been revising Film History for its fifth edition, and I found myself going back to our festival reports for succinct descriptions of films we considered important enough to figure in our updates of the late chapters.

Festivals also provide a delightful way to follow the careers of young filmmakers without realizing until later that one was doing so. For example, on July 15 the Venice festival announced that the head of the jury for the Giornate degli Autori program for promising filmmakers would be Israeli director Navad Lapid, whose Synonymes (2019) won the Golden Bear at Berlin last year. I wrote about it when we saw it at the Torino festival in November. The press release mentioned that Lapid had previously directed two other features, as well as many shorts. I had seen both of the features at Vancouver and blogged about them: Policeman (2011) and The Kindergarten Teacher (2014). So I had seen all of Lapid’s feature films without planning it that way. It is impressive to see the leap in complexity with Synonymes after two good films that I might never have seen had I not regularly visited that and other festivals.

Similarly, our long relationship with Ebertfest has given us a chance to meet both established and upcoming film artists. Thanks to Roger’s support, and the continuing efforts of Chaz Ebert and Nate Kohn, that remarkable event in Champaign-Urbana has become central to US film culture. Through Ebertfest we forged tight friendships with Jim Emerson, Matt Zoller Seitz, and other people working to broaden audiences and deepen appreciation of life-changing movies.

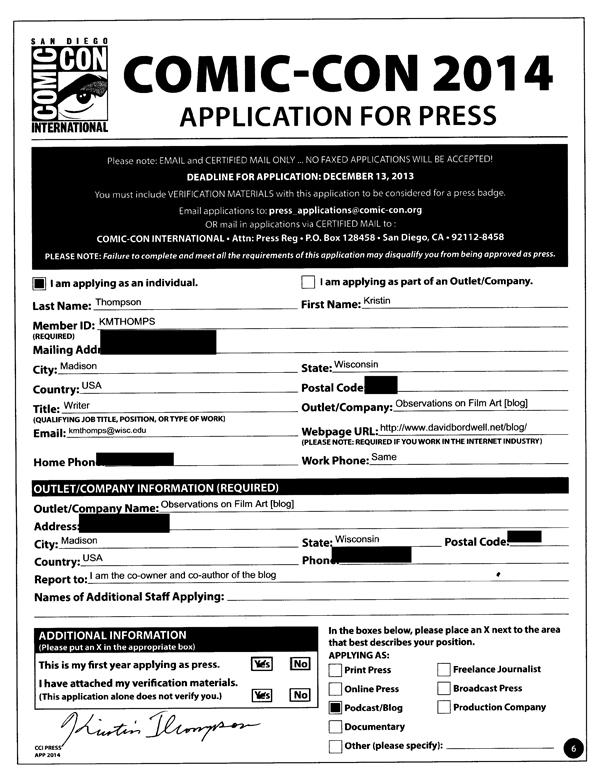

Apart from attending film festivals, getting press accreditation has benefited me in another situation. As part of my involvement in researching the Jackson Lord of the Rings films, I participated in a panel put on by TheOneRing.net at Comic-Con 2008. (I blogged about that banquet of popular culture here, here, and here.) Years later, I wanted to attend Comic-Con 2014 to witness the last of the big Hall H promotional events for a Jackson Tolkien adaptation, the third film of the Hobbit series. That time I wasn’t a guest, but I applied for a press pass based on being a blogger and got one.

I haven’t gone back, and I think my accreditation has lapsed, but as long as we keep the blog going, I probably have the option.

For us personally, the blog has played a role that a plain old-fashioned log of events would. (It’s worth remembering that “blog” comes from “weblog.”) We haven’t keep lists of the films we see, but sometimes I wish I had. Going back through the blog, though, is a great way of waxing nostalgic over the wonderful travels we have enjoyed and the friends in so many parts of the world that we have visited and shared meals with in happier circumstances–opportunities which we hope will come again.

We are reminded of films we saw, as well. Every now and then we have occasion to look back over older entries, seeking to create a link in a new blog. We often run across entries we don’t recall writing and titles we don’t remember seeing until the blog posts jog our memories. After a certain point we vowed to include illustrations in every entry, and that makes these visits to our past all the more vivid and enjoyable.

DB here:

I second everything KT has said. And more! See below.

Expanding the conversation and rapid response

Bologna, Piazza Maggiore screening of A Hard Day’s Night, 2014: Richard Koszarski, Diane Koszarski, and Lee Tsiantis.

Living online has given my retirement years a new dimension–of thinking, of access to art and ideas and new friends. I sometimes say that our blog is Internet 1.5–a publishing platform without the bombardment of instant comments. We’d get more traffic if we allowed comments, but (a) so many comments columns are insults to the human spirit and (b) we don’t want to spend time monitoring them. (But you can send an email.) The result is something like a more-or-less weekly magazine column, except that we can say what we want, write as long as we want, and include stills and clips. And there’s no editor saying we can’t use “diegetic.”

From another angle, the blog has been a substitute for my teaching. It allows me to develop ideas in ways that are informal, less precisely chiseled than they would be in a book or article. Call it “para-academic,” or “informal scholarship.” The blog has also let me send out communiqués about research findings around movies I was studying in Brussels (say, here or here) or at the Library of Congress (here and here). And, as Kristin mentioned I think the blog has encouraged me to write more conversationally than an academic publication would.

Retirement has encouraged me to think through recent events in film culture more fully than I could when I was teaching, and so some blog entries have become more topical. The big example is my decision to write about the digital conversion of exhibition back in 2011. I thought that somebody could record things as they were happening on the ground, and I tried to do that in a series of entries. One looked at how a small theatre in Harmony, Minnesota, confronted the crisis.

That series in turn became a little digital book that has generated a surprising amount of interest and remains, I think, a useful thumbnail history of a transitional period. From another angle, our interest in Christopher Nolan’s films allowed us to write about them as they came out, and then to revisit them in a broader perspective in another digital book, now in its second edition. It ruffled some feathers, leading me to speculations about blunt-force cinephilia. As ever, the blog proved a good forum for developing further ideas.

Speaking of new editions, having a web presence has enabled us to make available out-of-print versions of our work. Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment was put up on the main website in its original 1985 form, but I revamped both Planet Hong Kong and On the History of Film Style for digital editions when my publisher put them out of print. For both, I was able to use blog entries (here and here) to introduce them to a wider range of readers than would probably learn of them otherwise. It’s been gratifying to see both used as textbooks in courses as well.

Go back to the “para-academic” idea. I’ve been surprised to see that while academics have been supportive of our online efforts, they seem still to treat them as secondary to our print publications. By contrast, I’ve learned that there are a great many people who love films but who have found a lot of academic talk about cinema intimidating, dense, or dull. Some of these cinephiles are interested in ideas, if those ideas are presented in concrete and vivid ways. Our blog entries try to bring our notions about film form and style, about film history and film experience, to those readers.

An example is my never-ending crusade against reflectionist interpretation, the idea that a movie coming out today (well, maybe no movie is coming out tomorrow) reflects the Zeitgeist or national character or current events in a straightforward way. I won’t bore you with my arguments against this idea (see here and here and here), but without a blog I don’t think I’d be able to ride this hobby horse so intently. Thanks to the rapid-response capability of blogging, I can draw on current releases from The Dark Knight to The Hunt. I don’t know if I’ve convinced anybody that we can talk about film and culture more subtly if we take into account form, style, and genre. But the opportunity to use recent releases as AV demos has helped me refine my case.

This isn’t “popularizing” our research, I think. It’s an effort to see how research can stimulate people. Many readers, I think, know us only through the blog, and that’s fine. I like reader-friendly texts. I like to read in art history, cognitive psychology, music history, philosophy, and the like, but I’m not equipped to grasp the most technical literature in those fields. I need the “outreach” publications of Gombrich, Barzun, Baxandall, Sontag, Pinker, Taruskin, Hogan, Alex Ross, Mary Beard, Noël Carroll, and the many more academics and intellectuals who are not only researchers but, in the strongest sense, writers.

People

Hong Kong International Film Festival 2011: Joanna Lee, Michael Campi, and Ken Smith.

The blog has given us a chance to call attention to institutions we think deserve wider recognition. Those include the Arthouse Convergence, the Danish Film Institute and its archive, the Konrad Wolf Film School at Babelsberg, the Fox archive, the AMPAS archive, the Munich Film Archive, the Austrian Film Archive, George Eastman House (and its magnificent Nitrate Fest), and of course our stalwart rock through the years, the Royal Film Archive of Belgium (now called Cinematek). There’s our own Cinematheque too, as well as little theatres we come across in our travels (here and there). We even find a “lost” film on home turf. There’s the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp, which has proven endlessly stimulating to my thinking (and viewing). And of course there’s the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; we try to cover its annual get-together.

We also like supporting hard-working distributors like Milestone (and here), Flicker Alley, Editions Filmmuseum, and again of course Criterion, who devote great energy to opening up unknown byways of cinema. The Criterion team–Peter Becker, Kim Hendricksen, Grant Delin, Curtis Tsui, Elizabeth Pauker, Abbey Lustgarten, Susan Arosteguy, and many others–have made our lives continually exhilarating.

The blog has brought us closer to film artists too. At Ebertfest Kristin interviewed Nina Paley, and I got to talk to Doc Erickson about his long career working at Paramount and with Hitchcock. We’ve done a couple of interviews with director/screenwriter David Koepp (here and here), and Kristin questioned archival honchos Mike Pogorzelski and Schawn Belston about the prospect for a celestial multiplex–which even streaming is unlikely to deliver. We got to meet Bill Forsyth, Terence Davies, James Mangold, and Damien Chazelle, and because we try to understand the creative choices filmmakers face, we got to ask them about their craft.

As for critics–well, there are too many to mention here. Online and at festivals, we’ve come closer to a great many smart, dedicated critics and reviewers I have to mention at least Manohla Dargis, Kent Jones, Dave Kehr (now a sterling archivist), Justin Chang, Chuck Stephens, Bérénice Reynaud, and the Venice College team (Glenn Kenny, Stephanie Zacharek, Mick LaSalle, Michael Phillips, Chris Vognar, Ty Burr, all under the avuncular guidance of Peter Cowie).

The rapid-response advantage has also given us the opportunity to celebrate colleagues, particularly when they’ve written books we think cinephiles would enjoy. Then there are the colleagues we mourn. In the last year, the deaths have come quickly. I haven’t fully come to terms with the loss of Peter Wollen, Paul Spehr, Thomas Elsaesser, and Sally Banes. But we have acknowledged the importance of others who touched our lives, from Andrew Sarris and Edward Yang to Richard Corliss and Edward Branigan and of course Donald Richie and Roger Ebert. Necrology, the blog has taught me, is a heavy obligation.

On a less somber chord, the blog has given us the happy chance to host many excellent guest bloggers. We tapped them because their research is first-rate, and they widen out our explorations of film art within film history. So feel free to visit the contributions of:

Matthew Bernstein on Preston Sturges’ cleverness.

Kelley Conway on three women of Cannes, on French Films at Vancouver, and on La La Land.

Leslie Midkiff DeBauche on silent-era fangirls.

Eric Dienstfrey on recording and mixing in La La Land.

Rory Kelly on the character arc in Hollywood screenwriting.

Charles Maland on James Agee.

Nicola Mazzanti on silent frame rates.

Amanda McQueen on La La Land as a modern musical.

Tim Smith on eye-scanning and watching There Will Be Blood.

Malcolm Turvey on mirror neurons.

Jim Udden on visiting the set of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s The Assassin and the film that resulted.

David Vanden Bossche on 3D in Europe.

And of course the many guest entries by our collaborator on our Criterion Channel series Jeff Smith, who has written about Foreign Correspondent, Trumbo, The Player, The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Atmos sound system, Memories of Underdevelopment, Three Colors: Red, Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood (here and here), True Stories, Breaking the Waves, and Oscar song nominations (here and here and here and here). Watch for Jeff’s upcoming entry on Ennio Morricone.

Back in 2011, we put together a collection of blog entries as a book: Minding Movies: Observations on the Art, Craft, and Business of Filmmaking (University of Chicago Press). It consisted of 31 entries, grouped in rough thematic sections. This leads us to muse on how many books one thousand entries equates to. That’s roughly 32, though far from all of our entries are worth anthologizing. (The entire blog, however, is being archived by the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research here on campus.) Could we have used our time better in writing actual books? We think not. There is a pleasure in writing on minor subjects occasionally and in getting our thoughts to the reading public immediately. Books, after all, require more research than we put into most of our entries, and there is the editorial and publishing process to go through. And we are past the points in our career where we need to expand our CVs.

In short, although we occasionally feel uninspired, especially in these days of no travel, limited socializing, and practically no theatrical film exhibition, we are glad that we started the blog nearly fourteen years ago. Once those activities resume, we’ll have the places we go, the friends we pal around with, and the movies we see to write about. We seriously doubt that we will ever make it to 2000 entries, but who knows?

Venice International Film Festival, 2019. Photo by Gerwin Tamsma.