Archive for the 'People we like' Category

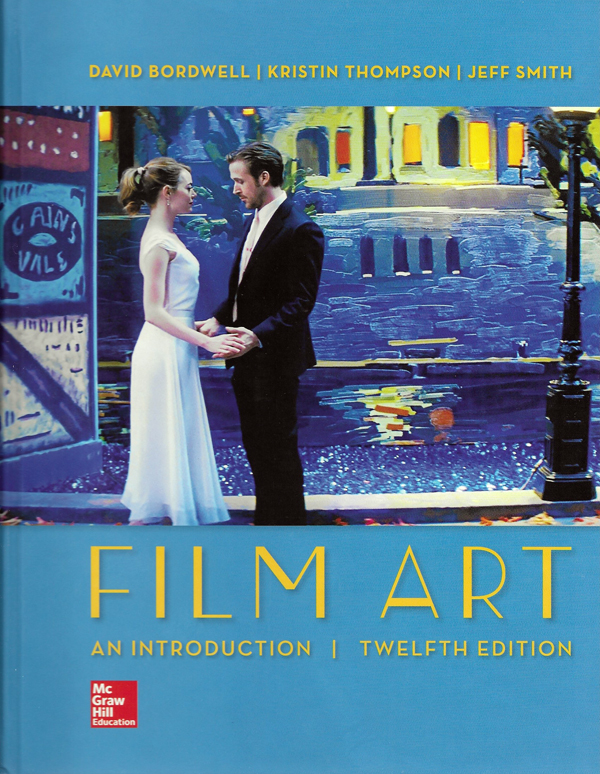

Frisky at forty: FILM ART, 12th edition

DB here:

The first edition of Film Art: An Introduction rolled into an unsuspecting world in 1979. Its butterscotch jacket enclosed 339 pages of text and black-and-white illustrations. It was, I think, the first film studies textbook to use frame enlargements instead of production stills. It was definitely the first to argue for a systematic aesthetic of cinema integrating principles of form (narrative/nonnarrative) with style (techniques of the medium). Our goal, of course, was to enhance the readers’ appreciation of the range and power of film as an art form.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

Not that there wasn’t a lot of room for improvement. Across three publishers–Addison-Wesley, then Knopf, and finally McGraw-Hill–the book has gained subtlety, precision, bulk, and color images. It now has a suite of online supplements in the form of aids for teachers and video clips for student reference, and the website you’re now visiting. Then there’s our streaming series on the Criterion Channel.

The core of our efforts remain the ideas and information we explore in the text. That material, happy to say, has found support among teachers, scholars, and writers of other textbooks. Through their suggestions and criticisms, we’ve had four decades to refine what Kristin and I initially set out, and on the eleventh edition Jeff Smith joined us to make things even better.

What’s new about this twelfth edition? Of course, we’ve updated it. We incorporate examples from Get Out, Son of Saul, mother!, Moonlight, Guardians of the Galaxy, Tiny Furniture, Inside Man, Wonderstruck, Dunkirk, Fences, Manchester by the Sea, Baby Driver, The Big Sick, Hell or High Water, Hostiles, A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night, The Blind Side, Opéra Mouffe, My Life as a Zucchini, Kubo and the Two Strings, Lady Bird, Birdman, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Tangerine, A Ghost Story, Snowpiercer, The Grand Budapest Hotel, and other recent titles.

One of the biggest changes involves the addition of an analysis of social and political ideology in Ali: Fear Eats the Soul. This detailed look at Fassbinder’s melodrama of prejudice replaces our study of masculinity and violence in Raging Bull. That earlier piece will be posted for free access on this site, joining analyses from earlier editions on this page.

The most evident difference, signaled on the cover you see above, is a new case study of how a film gets made.

Production: The hows and whys

The book’s opening chapter,”Film as Art: Creativity, Technology, and Business,” matters a lot to us. We try to provide concrete, systematically organized information about how people work with technology and within institutions to implement the techniques we’ll survey in later chapters. At the same time, our discussion of production, distribution, and exhibition tries to show how filmmaking institutions shape creative choices about form and style. Perhaps because we try to make those choices down-to-earth, we’ve been pleased to find that Film Art is used in film production courses.

For several editions, Michael Mann’s Collateral served us well as a model of how decision-making in the production process shaped the final film. We thought, however, it was time to refresh that chapter, and La La Land provided us rich opportunities. We had already written blog entries (here and here) about aspects of the film, but we wanted learn more about how it had been created.

Made by a director not much older than our students, La La Land was perfect for a book that tries to be both up-to-date and sensitive to film history. From the burst of ensemble energy in the opening traffic jam to the parallel-reality ballet at the end, Damien Chazelle’s film was both contemporary and classical, what Kristin calls “a modern, old-fashioned musical.” We thought it would help students see that a young filmmaker can draw on tradition while staying firmly in our moment.

The film’s production decisions were well-documented, so we were able to trace four areas of creative choice. By considering the film’s mise-en-scene, camerawork, editing, and sound, we could set up the major stylistic categories to come in later chapters. For example, Jeff could point out unique features of Justin Hurwitz’s score.

We were lucky to get guidance from Damien himself. He reviewed our analysis, and then went far beyond the call of duty. He came to Madison to talk with our students (chronicled here). He sat for interviews with the Criterion Channel on Jean Rouch and Maurice Pialat. He did three Q & A’s. He even took snapshots with his fans.

And Damien energetically helped us secure rights to the cover image, a process that all writers of film books approach with fear and trembling. In short, he proved a total mensch. The fact that he had already read our work when we first contacted him encouraged us in the belief that we might be helping young filmmakers find their way.

Film Art wherever you go

Film Art is now available in a variety of formats and prices. The print edition is now a looseleaf, unbound one. Bound copies still circulate for rental. Students may also rent or buy the e-book edition, which comes packaged as a digital resource called Connect. It’s possible to merge some of these alternatives. The various options for getting the book are charted here.

The Connect package includes teaching aids for the instructor (self-tests, quizzes) and access to thirty-six film extracts, courtesy of the Criterion and Janus companies. There are also four fine videos on production practice by our colleague Erik Gunneson.

As I discussed at exhausting length when I previewed our new edition of Film History: An Introduction, the variety of formats for the book reflects not only changes in technology and the publishing market but also changes in consumer preferences.

However it’s accessed, Film Art: An Introduction still makes us happy. We’ve tried our hardest to help readers understand a bit more about the techniques and effects of cinema. As we point out in the book, thanks to smartphones everybody is a filmmaker now. We think that students’ hands-on experience prepares them for our efforts to understand the creative choices filmmakers have faced from the very beginning.

Thanks as ever to the staff at McGraw-Hill: our editor Sarah Remington and the team consisting of Danielle Clement, Sue Culbertson, Maryellen Curley, Joni Fraser, Ann Marie Jannett, and Elizabeth Murphy. Thanks as well to Kaitlin Fyfe and Erik Gunneson here at the Department of Communication Arts, UW–Madison. And of course thanks to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, and their colleagues at Criterion.

Instructors who want to learn more about this edition can find a McGraw-Hill representative here.

Jeff Smith, who wrote the analysis of Ali: Fear Eats the Soul for our book, also provided an incisive discussion of staging in the film for our series on the Criterion Channel.

There’s a fuller account of how we came to write Film Art in our announcement of the previous edition.

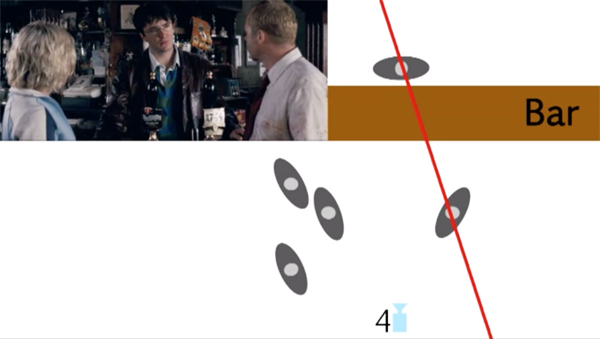

Video supplement: Shifting the Axis of Action in Shaun of the Dead.

Reporting from the Wisconsin Film Festival 2019

Hotel by the River (2018).

Kristin here:

The Wisconsin Film Festival is all too rapidly approaching its end, so it’s time for a summary of some of the highlights so far.

New films from around the world

We have not quite managed to catch up with all the recent films by Korean director Hong Sang-soo, but we took a step closer with Hotel by the River. It’s an impressive film, in part by virtue of its setting. The Hotel Heimat stands beside a river which is covered in ice and snow. Even the further shore with its mountains, is reduced to shades of light gray in the misty, cold light. All of this is enhanced by the black-and-white cinematography that creates a background against which the characters and the small trees create simple, austere compositions.

The story involves an aging poet who somehow senses that he is going to die soon and settles in at the hotel to wait for death. His two sons, one a well-known art-film director with a creative block and the other secretly divorced, come to visit. A young woman who has recently broken up with her married lover is visited by a sympathetic character who may be her sister, cousin, or friend. They encounter the poet by the river, and he compliments them effusively for adding to the beauty of the scene. Conversations about life ensue. The women take naps, the men bicker. Sang-soo’s typical parallels and repetitions unfold. It’s a lovely film.

Yomeddine, an Egyptian film, created something of a stir last year when it was shown in competition at Cannes. It was a surprising choice, given that it is writer-director A. B. Shawky’s first feature.

It’s also a modest, low-budget film, and like so many such films made in countries with limited production, it’s a road movie. No need to build sets or use complex lighting. The two central characters are Beshay, dropped off as a small child at a leper colony by his father, and Obama, a young orphan who knows nothing of his birth parents. Coincidentally, they both come from Qena, a city north of Luxor on the great Qena Bend of the Nile. Longing for links to their origins, the two set out there. At first they ride in the donkey cart that Beshay uses in his work as a garbage-picker, but later, when the donkey dies, they travel on foot and occasionally by train, riding without benefit of tickets.

There’s no indication where the orphanage and leper colony are and thus how long a trek the two face. I’m pretty familiar with the Nile, but they follow the large canals and train tracks that run parallel to the river on both banks. The villages along their route look pretty much alike. Shortly into the trip, however, Shawky suddenly confronts us with the Meidum pyramid (above), which acts as a handy landmark to reveal that the pair have a long way to go. It’s Shawky’s only display of an ancient site. Beshay and Obama have no idea what it is, but they explore it and spend the night in its small chapel.

Yomeddine is a likeable film blending humor, pathos, and a little suspense as it follows the pair on their quest. It’s also a plea for tolerance. Beshay’s deformities scare off those who wrongly think that leprosy is contagious (with treatment it is not), and Obama is denigrated by his classmates as “the Nubian,” for his relatively dark skin. Their sometimes prickly odd-couple friendship is a demonstration of how people of various backgrounds, including those on the margins of society, can get along. That, I suspect, is what led Cannes programmers to include it in the competition.

Overall it’s a well-made, entertaining film, perhaps an indication that we shall see more from Beshay on the festival circuit in the future.

[April 19: Yomeddine won the Audience Favorite Narrative Feature at the Wisconsin Film Festival.]

Ralph and Venellope Back in 3D

Phil Johnston with Ben Reiser, Senior Programmer, Wisconsin Film Festival.

UW–Madison grad Phil Johnston was a key participant in the festival. Not only did he program one of his favorites, Ozu’s Good Morning (1959), but he also visited a class and ran a public event around Wreck-It Ralph 2: Ralph Breaks the Internet. Phil was a writer on both entries and co-director on the second, while also providing screenplays for Zootopia (2016) and Cedar Rapids (2011). We’re very proud of him, and we were happy to welcome him back home.

I love both the Wreck-It Ralph films, but I don’t like to go to hit movies early in their runs. We usually wait a few weeks till the crowds die down. As I recently pointed out, though, that means risking no longer having the option of seeing a 3D film in that format. So it happened with both Ralph Breaks the Internet and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse.

Fortunately for us, the UW Cinematheque added permanent 3D capacity to its projection options, so Ralph 2 was shown in that format. The 3D much enhances the sense of being surrounded by the myriad “websites” in the scenes showing general views of “the internet,” as well as by the vehicles and netizens that flash past in their travels.

Both Ralph films display a non-stop inventiveness, and I agree with Peter Debruge’s comment that Wreck-It-Ralph “ranks among the studio’s very best toons.” The sequel is, if anything, even better. The scene in which Venellope von Schweetz confronts the full panoply of Disney princesses and tries to prove herself one of them became a classic before the film was even released.

The notion of Venellope moving from the sickly sweet “Sugar Rush” arcade game to the wildly dangerous online “Slaughter Race” (see bottom) is a great concept to begin with, and her rendition of her “Disney princess” song, “A Place Called Slaughter Race” is hilarious. The film was robbed, in my opinion, when her song didn’t get nominated for a Oscar.

The film has jokes to burn, as in the clever puns on the signs that flash in the internet and game scenes. I look forward to being able to freeze-frame the images to catch the many I missed. Unfortunately the Blu-ray release will not be in 3D. Disney has been phasing out releasing its 3D films in that format ever since Frozen, but you could for a time order such discs from abroad. (Other studios are following suit, and our 3D copy of Into the Spider-Verse is wending its way from Italy as I type.) I am told that the only 3D Ralph will be the Japanese version, at something like $80. Fortunately, it looks great in 2D as well, but I’m glad to have seen it on the big screen in 3D once.

So old they’re new again

Jivaro (1954).

Recent restorations have become a increasingly important component of our festival’s wide variety of offerings. Selections from the previous year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna are now regularly programmed, and we had visiting curators presenting their new projects. (For a brief rundown of the Bologna offerings this year, see here.)

Another film taking advantage of the Cinematheque’s new 3D capacity was Jivaro, a jungle-adventure film of the type more popular in the 1950s and 1960s than it is now. Having seen a such films when growing up, I can say that Jivaro is better than many of its type.

It was made late in the brief early 1950s vogue for 3D, so late in fact that the studio decided to release it only in 2D. One attraction of its screening at the WFF was the fact that it was screening publicly for the first time ever in its intended format. Bob Furmanek, 3D devotee and expert, introduced the film and took questions afterward; he has been a driving force in the restoration of this and many other 3D films. (His immensely valuable site is here.) Below Bob shows one of the polarizing filters used in projection booths.

The film was highly enjoyable, partly for the 3D (shrunken heads thrust into the lens and spears coming at us!) and partly for the comfortable familiarity of its genre tropes. There’s the genial South American trader who has gained the respect of the locals, the seemingly deluded adventurer with a map to a lost treasure who turns out to be right, the gorgeous woman who shows up dressed in tight blouse, skirt, and high heels, the beautiful local girl in hopeless love with a white man, and so on. (The beautiful girl was an early role for Rita Moreno, who labored as an all-purpose-ethnic bit player for years before West Side Story made her a star.) Leads Fernando Lamas and Rhonda Fleming supply beefcake and cheesecake, respectively, at regular intervals. Lamas (as you can see above) barely buttoned his shirt across the whole film. It’s hot in jungles.

For those with 3D TVs, Jivaro is already out on Blu-ray.

The Museum of Modern Art has followed up its restoration of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) with one of Forbidden Paradise (1924). Both were shown at this year’s festival. We saw Rosita at the 2017 Venice International Film Festival and wrote about it then. In preparing my book Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (2005; available free as a PDF here), I saw an incomplete copy of one preserved in the Czech film archive–a key element in constructing this new version. Naturally I was eager to see the new scenes and much-improved visual quality of the MOMA restoration. Archivist Katie Trainor was present to explain the process, which yielded a version that is about 90% the length of the original.

Of all Lubitsch’s Hollywood films, this is the one that most looks back to his German features of the late 1910s and early 1920s. For one thing, his frequent star of that period, Pola Negri, was by now in Hollywood and worked here with him again here, their sole Hollywood collaboration. She stars in a highly fanciful tale of Catherine the Great, and the quasi-Expressionistic sets present an appropriate version of historical style. The set in the frame above (taken from a 35mm print, not the restored version) is my favorite, with its lugubrious creatures crouched atop the wall. Grotesque sphinxes? (The designer might have been thinking of the the two beautiful granite sphinxes of Amenhotep III that sit to this day by the Neva River in front of the Academy of Arts, though they were brought to Russia decades after Catherine’s reign.) Or just elaborate gargoyles?

The plot centers around a brief affair between a young officer (Rod La Rocque) and the licentious Catherine. A brief attempt at revolution flares up. All this is deftly dealt with by the Lord Chamberlain, played by Adolf Menjou, hamming it up with eye-rolls and knowing chuckles.

It’s not first-rate Lubitsch, largely lacking the lightness that one associates with the director, and which he had already achieved in his second Hollywood film, The Marriage Circle (1924). But it’s a pleasant entertainment, and the set and costume designs are visually engaging–especially in this excellent new restoration.

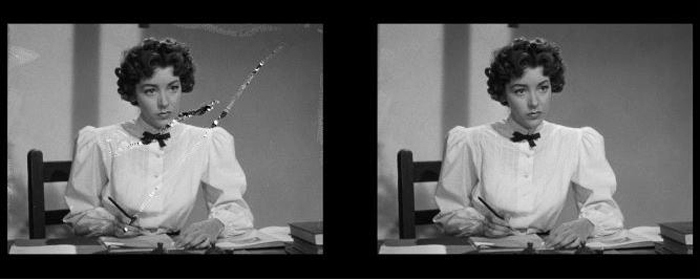

David watched None Shall Escape (1944) for his book on 1940s Hollywood, but I was unfamiliar with it until its restored version was shown here as one of the Il Cinema Ritrovato contributions. The film was originally made by Columbia and was presented at our fest in a 4K restoration from Sony Pictures Entertainment, the parent company of Columbia. Rita Belda, SPE’s Vice President of asset management, was here to explain the complicated process. She summarizes it here as well.

The film had been carefully preserved, probably because of its historical importance as a unique fictional depiction of Nazi atrocities. The original negative and three preservation positives survived. These had the usual scratches and tears, as evidenced in the first comparison image above. A significant challenge, however, was that the prints had all been lacquered in a misguided attempt to preserve them. The result was staining throughout, evident in both comparison images. Digital removal allowed for a stunningly clear image throughout the finished version.

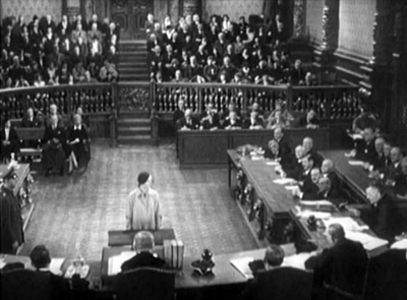

None Shall Escape is notable as the only Hollywood film made during the war to depict major aspects of the Holocaust. It begins with a frame story set in the future. This postwar trial of Nazi criminals remarkably prefigures the Nuremberg trials. Testimony is given against a single officer, who stands in for all the accused officers and collaborators. Wilhelm Grimm begins as a schoolteacher in a small Polish city but proves so devoted to the Nazi cause that he rapidly rises through the ranks. After the city is seized during the German invasion, Grimm comes to rule the city. At the trial, townsfolk who had resisted and suffered under his domination testify, and their stories unfold as a series of lengthy flashbacks.

The film is an effective and moving drama, not least because it demonstrates the explicitness with which it was possible to depict Naziism in this period. It shows, as Hitler’s Children (1943) did, the insidious indoctrination of young people by the Nazi party. But no other film depicted the rounding up of Jews and their dispatch to concentrations camps–named as such.

Director André De Toth, though not a top auteur, again proves the value of sheer skill and artistry in filmmaking, a value that David recently discussed in relation to Michael Curtiz. None Shall Escape is an impressive example of the power of the classical Hollywood system–and a beautiful film, as one might expect from cinematographer Lee Garmes. Marsha Hunt gives a moving performance as Marja, another schoolteacher who fearlessly persists in opposing Grimm and his oppression of the townspeople; it is a pity that she never achieved the stardom that she merited.

Perhaps most notably, De Toth stages a powerful scene in which Jews rebel against being packed into trains and are ruthlessly mowed down by their captors. It must have given many Americans a first glimpse of what would soon be revealed by newsreels and personal testimony.

Now, back to the movies. More festival coverage to come, when we get time to write!

For more on early 3D, see David’s entry on Dial M for Murder.

Ralph Breaks the Internet (2018).

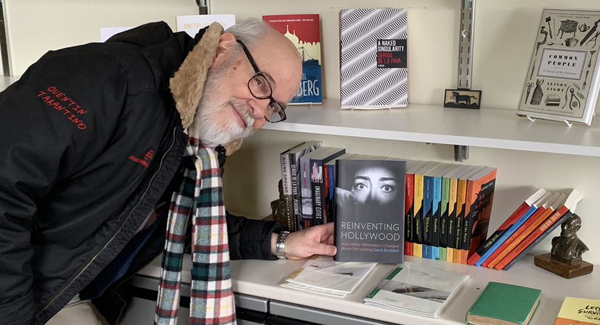

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Extra-credit reading and viewing

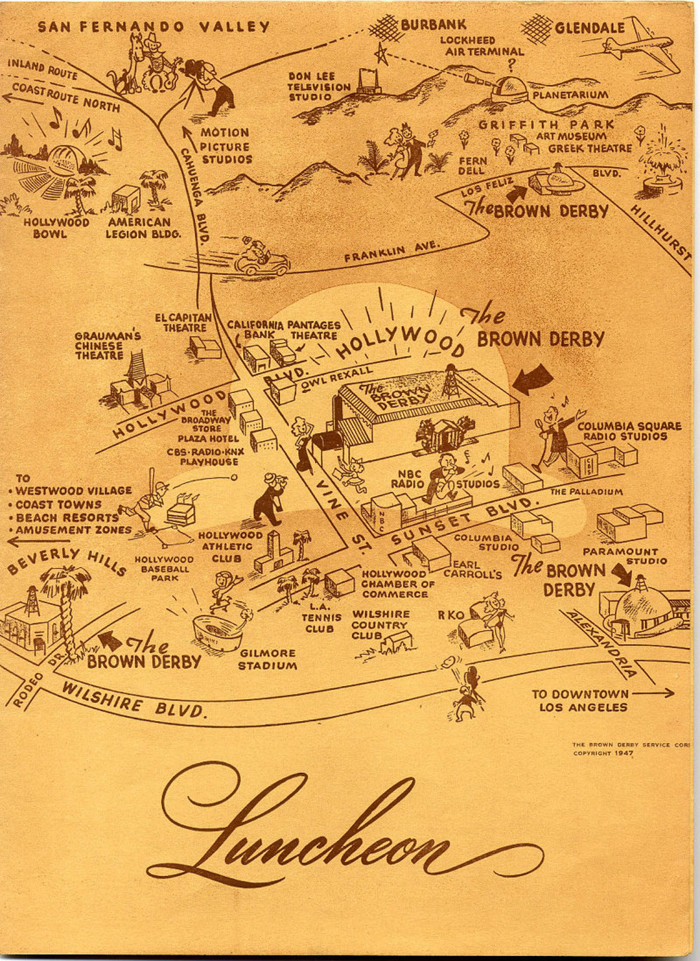

Brown Derby lunch menu.

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted at some point. I hope these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

Prosperity helps the movies

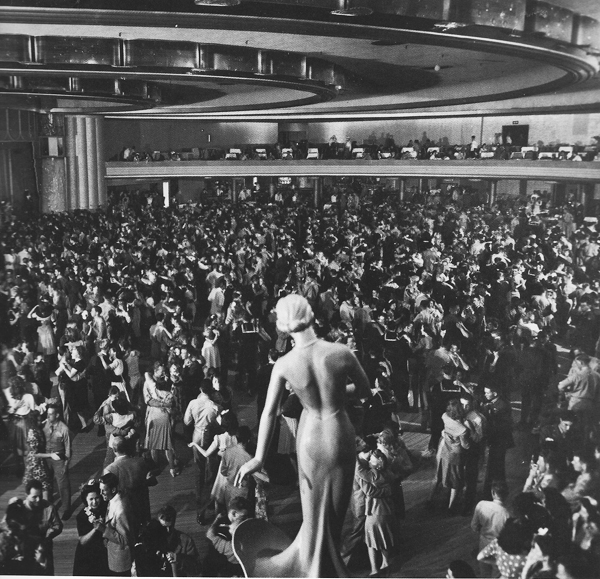

Lobby, Loew’s theatre, Rochester, New York, 1940.

Apart from studies of single creators, film historians have often sought to go macro, to tie the films to a broader cultural context. Elsewhere on this site I’ve criticized claims that films directly reflect national character, a zeitgeist, or a mood of the moment. There’s no denying that films bear the traces of the societies that make them. The question is how to understand that process—and how to explain it.

I vote for seeing cultural material as filtered through the constraints and choices of the institutions that filmmakers work in. Writers, directors, producers, and other participants (deliberately or unwittingly) pick out bits of cultural flotsam and reshape them. Buzzy ideas become plot premises. New technologies fulfill old functions. The newspaper-headline montages of the 1930s are replaced by shots of chyrons and cable news feeds today. Stereotypes become characters–sometimes unstereotypical ones. Not reflection, then, but refraction, with agents and social institutions recasting some trends that are out there.

But the macro level shapes cinema in another way: as a set of economic and technological preconditions. Around 1900, a society without a market economy and access to machine technology couldn’t have invented cinema. Before the smartphone, people living in certain countries lacked the infrastructure to access the Internet.

Historians sometimes distinguish between proximate causes—factors we can trace with some specificity—and distal causes, those more basic and pervasive preconditions that provide a background for the proximate causes. Along these lines, I wish I’d drawn on Robert J. Gordon’s 2016 masterwork, The Rise and Fall of American Growth.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Gordon proposes that the century from 1870 to 1970 saw five great clusters of technological innovations: electricity, urban sanitation, chemicals and pharmaceuticals, the internal combustion engine, and modern communication systems. Most became feasible at the end of the nineteenth century, but they took some years to develop, starting to disseminate through the US population from 1920 onward. They peaked, he claims, by 1970 but a significant threshold was crossed around 1940.

Thanks to the Great Depression, FDR’s recovery scheme, and the start of World War II, both the American economy and most American lifestyles improved dramatically. Home electricity, refrigerators, washing machines, radios, telephones, central heating, cheap clothing, sanitation (no more horse droppings on Main Street), the rise of life expectancy, and the fall of infant mortality transformed everyday life. Most of these improvements were tied to the growth of cities. As Gordon puts it:

Except in the rural south, daily life for every American changed beyond recognition between 1870 and 1940. Urbanization brought fundamental change. The percentage of the population living in urban America—that is, towns or cities having more than 2,500 population—grew from 25 percent to 57 percent. By 1940, many fewer Americans were isolated on farms, far from urban civilization, culture, and information.

Reinventing Hollywood emphasized the boom in movie attendance that took off around 1940. Surely American migration to cities fed into this.

The growth of the film industry in the early and mid-Forties parallels a surge in everyday circumstances as well. By 1950, 92 percent of households had a motor vehicle. Penicillin and streptomycin had begun to drastically reduce instances of pneumonia, rheumatic fever, syphilis, and tuberculosis, while a new vaccine eliminated polio. And the rural population continued to dwindle, particularly when people were lured by the fat paychecks in war-related industries.

Did the diffusion of the major consumer technologies through American society directly affect the form and style of the films? No. Just as the struggle with the Axis didn’t demand flashback structure or voice-over narration, neither did the economic forces in society at large. But they did provide a basis for a leisure economy in which filmgoing could flourish, especially when the war cut down rival entertainments and provided more discretionary income. I discuss these processes at some length in Reinventing. Likewise, radio technology didn’t automatically create new narrational devices like voice-over and auditory flashbacks. Radio’s creative artists chose to develop specific techniques to achieve immediate ends. The rise in American standards of living is not a proximate cause but a powerful precondition for the 1940s surge in innovative storytelling. I could have signaled that factor more strongly.

Hanging out

Hollywood Palladium Café.

If the bottom-up approach I tried out is to get anywhere, it needs to show that there’s a community of creators aware of what other folks are doing. Accordingly, the first chapter of Reinventing argues for the importance of Hollywood as bristling with social networks that facilitated cooperation within competition.

Formal organizations, which Kristin, Janet Staiger, and I traced out in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, include professional associations, supply firms, trade papers, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. These served as clearing-houses for filmmaking information. Reinventing adds in the more informal ties among personnel on the job or outside work hours (partying, playing cards or polo). In that era of loanouts and independent production, people who socialized might wind up working together.

I mention a few Hollywood hangouts, but now I wish I’d done more with the night spots that sprang up in the 1930s, most notably the Hollywood Derby, the Cocoanut Grove, and the Trocadero.

Most of the watering holes lingered into the Forties, when new attractions like Ciro’s and the Mocambo were added to the list. There were some more risqué ones, like Club Zombie and Florentine Gardens, which advertised topless/ bottomless performers. And there was the vast Palladium café, with a dance floor that could accommodate 7500 people.

These and many more venues are featured in magnificent photos in Jim Heiman’s Out with the Stars: Hollywood Nightlife in the Golden Era. Yes, everybody is shown smoking cigarettes.

I did edge into this area by discussing Breakfast in Hollywood (1946) as a network narrative. It features Bonita Granville, Zasu Pitts, Spike Jones, Nat King Cole, Hedda Hopper, and, I’m told, the mothers of Gary Cooper and Joan Crawford. The movie was a spinoff of a current radio show that broadcast from Sardi’s before moving to a dedicated venue on Vine Street. An enormous sign promised “Glorified Ham and Eggs from Pan to Mouth.”

The minimal switcheroo

Reinventing Hollywood surveys flashbacks, subjectivity, voice-over, ellipsis, multiple-protagonist plots, and other techniques. They were taken up widely and explored in various directions.

But they weren’t brand-new. Apart from voice-over, of course, these storytelling strategies appeared fairly often in the silent era. And although the 1930s largely swerved away from these strategies, they did pop up occasionally. I discussed several examples, such as The Power and the Glory (1933), The Life of Vergie Winters (1934), Peter Ibbetson (1935), and the crazed Poverty Row item The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

Tom Gunning reminded me of another important precursor. Confession (1937), a Warners melodrama starring Kay Francis, tells of a young woman becoming the prey of a suave but rapacious composer. When she leaves a supper club with him, he’s shot by the woman who has just performed a song. In the singer’s trial, she reveals that he seduced and abandoned her and that the young woman he tried to seduce is her daughter. The court goes fairly easy on her.

The tale is told through some devices that would proliferate in the 1940s. Voice-over monologue to let us in on a character’s thoughts? Check, although it’s very minimal. Flashback to illustrate trial testimony? Check, although that was already a fairly common option from the silent era onward. And a replay of events that show us an event from different viewpoints? Check, although another trial drama, the RKO Ann Harding vehicle The Witness Chair (1936) had pursued the same strategy. (It can be found as far back as The Woman Under Oath (1919), as discussed in an earlier entry.)

What makes Confession more interesting, as Tom also told me, is that it’s a maniacally close remake of Willi Forst’s Mazurka (1935). Here Pola Negri plays the avenging discarded lover. Joe May was a very talented director, but in Confession, he was content to copy the original scene for scene, and sometimes shot for shot. A portion of the German version’s first shot is re-used in the beginning of the American film.

The courtroom is one of several sets that are more or less replicated. Again, the Mazurka shot is first.

Both versions include a replay of an earlier scene. In the first instance, the daughter is unaware that her mother hovers in the hall outside. In the replay, we’re attached to the mother watching the young woman with her adopted mother. The parallel Mazurka sequences are on the top, the Confession ones below.

May’s remake supports a couple of points I made in the book. One source of Hollywood’s 1940s narrative ambitions was foreign cinema. French, German, and British films were exploring these techniques in the 1930s, and some relevant titles got exported to the US. A few were remade, with The Long Night (1947), based on Carné’s Le Jour se lève (1939), being one of the most famous. At the same time, some European directors, like May, started working in Hollywood. Julien Duvivier, for example, leaped into the new US trends with Lydia (1941), Tales of Manhattan (1942), and Flesh and Fantasy (1943).

Hollywood endlessly recycles material, as the new Star Is Born shows. Remakes weren’t as common then as they are now, but they did exist. We might see them as part of the process that includes the switcheroo, the habit of varying an existing premise or gimmick with a change that makes the thing look fresh. I suppose the most famous switcheroo comes in His Girl Friday (1940), where the male protagonist of The Front Page (1931) becomes a woman. Neatly, the name Hildy Johnson works both ways. Even Lydia can be seen as a switcheroo on Duvivier’s own Carnet de bal (1937). Everything, as we know, is grist for the Hollywood mill.

Most broadly, popular entertainment exemplifies what I call the variorum impulse, the urge to tweak or twist existing materials and devices. The aim is to produce something new that’s at once novel and familiar. More on the Variorum in a later entry.

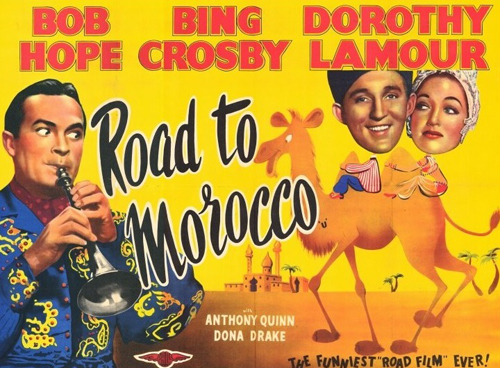

Bing and Bob

I’ve had reason to praise Gary Giddins elsewhere on this site, but I never got around to talking about the wonderful first volume of his biography of Bing Crosby. Now he’s come up with Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years 1940-1946. Of course he deals with the musical career in definitive fashion, but just as important for me is his in-depth coverage of Der Bingle’s movies.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

Reinventing, alas, devotes no space to Going My Way (1944), but after reading Giddins’ fifty pages on the film’s production, with sharp excursions into McCarey’s working methods and the tug-of-war about billing in the credits, I wish I had. It’s of course an extraordinary movie, loosely plotted and irresistible in its gentle momentum.

McCarey sold Crosby on the part as if he were peddling a modern High Concept project: “You’re going to play a hep priest.” Giddins carefully traces how the film took the country by storm and led to Crosby’s new, extraordinarily powerful contract with Paramount.

Bing enters my book in Chapter 11, as partner to Bob Hope in the zany Road films. These, along with other Hope vehicles, exemplify for me the acute movie-consciousness we find throughout the 1940s. Of course silent films and early talkies were often set among moviemakers (one of my favorites is Boy Meets Girl, 1938). But the theme shifted into higher gear in the 1940s and early 1950s, when we got films that exhumed Hollywood’s history (The Perils of Pauline, 1947; Singin’ in the Rain, 1952) and comic films that made fun of cinematic conventions. The latter is most wildly illustrated in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), but we get comparable cinematic in-jokes in the Road movies.

Giddins leads us behind the scenes, showing how the Road scripts, tentatively approved by the Breen Office, would get pulled apart during shooting and naughty bits of impromptu got shoved in in.

The writers aimed not only to make scripts funny but also to bamboozle censors. As Bing and Bob crisscrossed the set between takes, like fighters going to their corners, they would receive whispered zingers from personal gagmen, each star looking to unbalance the other; the constant comic rigor roused players and crew. Breen had no knowledge of the ad libs or how scenes would play.

Giddins is constantly throwing crosslights on these films. He shows, for instance, that the “high-velocity raillery” of The Road to Zanzibar (1941) owes something to producer Paul Jones, who had worked on Preston Sturges’ comedies. “The pace of the dialogue between crooner and comedian is impeccable, unforced, and funnier than the actual lines.”

To greater or lesser degree Giddins plumbs all the fourteen films Crosby made in these years, weaving them into the spectacular radio, touring, and recording career of one of the most popular stars in American entertainment. There’s plenty of sadness to go around too.

I could go on and on, as you know. After I finished the book I discovered George S. Kaufman’s 1945 play Hollywood Pinafore; or, The Lad Who Loved a Salary. It uses Arthur Sullivan’s score for H.M.S. Pinafore to mock the movie capital. Here’s a sample featuring the gossip columnist Louhedda:

Somehow all the weekly checks/definitely hinge on sex./ One man fills another’s shoes./Hard to tell whose baby’s whose./ Many autographs annoy/ Ella Raines and Myrna Loy./Goldwyn claims that all our ills/ Can be traced to double bills.

Et cetera. A bit labored, but cute.

Next time: Reinventing Hollywood and Happy Death Day 2U.

Thanks to Tom Gunning, Dan Morgan, Ally Nadia Field, Jim Lastra, Richard Neer, Jim Chandler, Mike Phillips, and Gary Kafer, as well as those who attended my lectures at the University of Chicago in January.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Yow.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. What a brain fart. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Sad!

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

UChi marketing guru Levi Stahl tweets: David Bordwell stops by the office but refuses to pose with his own book unless you also let him include Richard Stark’s Parker novels in the picture. It’s as close as I’ll get to greatness.

The Criterion Channel is coming back!

Breaking news! Last month ATT’s acquisition of Time Warner led to the announcement that FilmStruck, and the Criterion Channel thereon, would be discontinued. (Today I got my refund for the rest of my annual subscription.) But many film fans and filmmakers have kicked up a fine fuss. One especially robust bloc wrote directly to Warner Pictures head honcho Toby Emmerich. A second, equally strong letter followed.

Now we learn from Peter Becker of Criterion that the Channel is restarting in spring of 2019.

The Criterion Channel will be picking up where the old service left off, programming director spotlights and actor retrospectives featuring major Hollywood and international classics and hard-to-find discoveries from around the world, complete with special features like commentaries, behind-the-scenes footage, and original documentaries. We will continue with our guest programmer series, Adventures in Moviegoing. Our regular series like Art-House America, Split Screen, and Meet the Filmmakers, and our Ten Minutes or Less section will all live on, along with Tuesday’s Short + Feature and the Friday Night Double Feature, and of course our monthly fifteen-minute film school, Observations on Film Art.

Our library will also be available through WarnerMedia’s new consumer platform when it launches late next year, so once both services are live, Criterion fans will have even more ways to find the films they love.

We will be starting from scratch, with no subscribers, so we will need all the help we can get. The most valuable thing you can do to help now is go to Criterion.com/channel and sign up to be a Charter Subscriber, then tell your friends to sign up too. We need everyone who was a FilmStruck subscriber or who’s been tweeting and signing petitions and writing letters to come out and to sign up for the new service. We can’t do it without you!