Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Books not so briefly noted

“What a piece of junk!” Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope.

DB here:

Over there, across the room, a stack of more or less recently published books has haunted me for months. I wanted to tell you about them. True, I had plenty of excuses: My stay in Washington, a health nuisance, our trip to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, and our looming deadline for a new edition of Film History: An Introduction. But excuses aren’t necessarily good reasons. My delay was especially painful because the books were by friends.

So here’s some penance. As usual, some of the books I’ve read completely; others I’ve read only stretches of. But each is on a fascinating subject, by people of sound mind and impeccable character–in other words, exceptional researchers, thinkers, and writers.

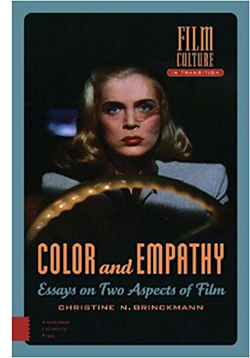

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Christine N. (Noll) Brinckmann is both a critic and a filmmaker. In Color and Empathy, she brings hands-on expertise to two subjects too often ignored. Her essays treat the handling of color in silent cinema, 1950s Hollywood, experimental film, and Claire Denis’s Beau Travail. On the empathy side, she analyzes its role in documentary, Hitchcock films, and Eric de Kuyper’s Casta Diva.

Noll is very good on what I’d call the “historical poetics” of color, starting from perceptual and technical aspects and moving to the ways conventions emerged historically. For example, she contrasts Pal Joey and Chungking Express: sharp-edged versus blurred, object colors versus ambient colors, narratively motivated color clusters versus poetic and associational ones. She introduces the useful concept of color “chords,” mingled hues that create motifs that weave through the film. With this concept she’s able to treat late 1950s Hollywood color comedies as having a “mannerist” style, with chords dissolving into moments of patches of pure abstraction. She finds this strategy in some very unexpected places; I never thought I’d need to look at Bob Hope’s Bachelor in Paradise again, but now it’s a must.

As a filmmaker, Noll is also sensitive to the bodily reactions of viewers. Empathy is one such general phenomenon. What I appreciated in her discussion was her eagerness to go beyond the usual sense of the term, which involves feeling for characters in an emotional register. By analyzing passages in Secret Agent and Frenzy, she also considers how visceral factors like motor mimicry play into our responses. She takes the face as the main arena of empathy, but gestures–like cracking open fingers closed in death–are central as well. Thanks to empathy, she notes, films align us with some fairly unpleasant people. “We have not invested any sympathy in the characters; we disapprove of their actions, yet wish them to succeed.”

As a filmmaker, Noll understands that films are made not with themes but with images and sounds, so her account of bodily engagement, like her analyses of color dynamics, is pervaded by the recognition that first of all a movie is a concrete experience engaging our senses and our minds. The critic can point to abstract meanings, but we’re also interested in the mechanics underlying those meanings, how movies arouse our appetites for action and emotion.

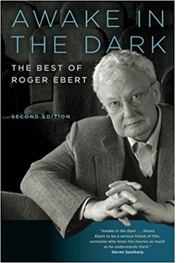

Two critics attuned to the many levels of a film’s appeals are represented in new collections. There’s now a second edition of Roger Ebert‘s Awake in the Dark: The Best of Roger Ebert, from the University of Chicago Press. The 2006 original, which contained his personal choice of his strongest reviews and essays through 2005, has been enhanced with new pieces on Roger’s favorite films from the years 2006-2012, the year before his death. Films covered are Pan’s Labyrinth, Juno, The Social Network, A Separation, and Argo, along with shorter notices on many more.

It’s clear that Roger’s abilities were undiminished despite his illness. As ever, he brings his own variety of empathy to the characters and story worlds displayed. His eye stayed sharp:”Del Toro moves between many of these scenes with a moving foreground wipe–an area of darkness, or a wall, or a tree. . .. The technique insists that his two worlds are not intercut, but live in edges of the same frame.” The dozens of pieces in the collection are full of warm, sensitive moments of appreciation. I have updated my introduction to add some further reflections on Roger’s legacy.

While Roger Ebert was starting his career in Chicago with a review of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967, Joseph McBride was at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, writing his own film criticism and working on his still valuable book on Orson Welles. A prodigy, yes. He moved to California the same year Kristin and I came to Wisconsin; we met him once, as I remember, just before he was about to leave. We’re kindred spirits, born sixteen days apart and bound by Boomer Auteurism.

Joe’s most famous screenplay is for Rock ‘n’ Roll High School, but he also scripted many of the AFI tributes. He’s a professional journalist and currently a university professor. But he is at bottom, as he readily admits, a book writer. His biographies of Capra, Spielberg, and Ford have become indispensable, while his memoir and analysis of Welles’ late career (What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?) is just as meticulously researched and intellectually ambitious.

Now Joe has given us a massive collection of his shorter pieces. Two Cheers for Hollywood, its ambivalent title echoing E. M. Forster’s Two Cheers for Democracy, includes a vast panorama of work. Journalist Joe, who has done over 15,000 interviews in his career, gives us a tempting sample here. He records encounters with screenwriters (Polonsky, Michael Wilson, Marguerite Roberts et al.) and directors (from Cukor and Wilder to Bernds, of Three Stooges fame). He talks with Stepin Fetchit in a Madison strip club and Peter O’Toole in the Beverly Wilshire (“his bony white hands and feet protruding from his royal purple robe like the wings of a great pale bird”). Saul Zaentz complains of “pseudo-stars” and Billy Wilder shows Walter Matthau how to rip out a phone cord in two jerks: “Zis is the first one, and the second zis is a ZUMP!” Each interview is prefaced by a thoughtful reflection on Joe’s own evolution as a writer.

Then there are the critical pieces, many of them magnificent. There’s the most detailed defense I’ve ever seen of the Coens, a nuanced investigation of Ford’s attitudes on race, a predictably acute account of Spielberg’s strengths and weaknesses, an appreciation of performance in Fahrenheit 451, a probing of Wild River (Kazan’s most Fordian film, methinks), and much, much more. The book contains 56 essays, all substantial. It runs to over 650 big pages. It lacks neither passion nor precision, just an index.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

Another Boomer Auteurist is William Paul. Bill did some film reviewing in his younger days but became an academic like Noll and Joe and me. Currently Professor of Film and Media Studies at Washington University of St. Louis, he has written fine books on Lubitsch’s American films and on the tie between modern horror and modern comedy. What has consumed him in recent years is an in-depth investigation of the history of the movie house. When Movies Were Theater: Architecture, Exhibition, and the Evolution of American Film is the result, and it’s a landmark study.

The broad historical arc moves, as you’d expect, from storefront theaters to picture palaces and then drive-ins and arthouses. But this is no simple account of buildings. Bill argues that the manner of presentation shaped the rise of the feature film, the recurring strategy of roadshows, the demands for double bills, and other factors of film form and industry conduct.

Bill suggests that the 1910s demand for “life-size figures” in film might have been a response to theater size, and he speculates that the move to closer shots in the 1920s might reflect enlarging venues. Makes you wonder if “intensified continuity” of the 1960s and thereafter owes something not only to TV as the ultimate destination of the images but also to the cramped screens of early “twinned” houses, those sticky-floored abominations.

As usually happens when a good historian dives deep, you get surprises. Bill uncovers floor plans with seats facing in the wrong directions, horseshoe-shaped venues, auditoriums packed with pillars, and other peculiarities. One counterintuitive thing that I learned was that screens were rather small for most of film history. A screen for a palace seating a thousand people might be only twenty feet across. Bill’s frames from Footlight Parade and Saboteur show views from the back of a playhouse, and they indicate that often the proscenium area wasn’t filled by the screen, which was cloaked in black masking.

The Hitchcock is of course a studio reconstruction of Radio City Music Hall, but Bill indicates that the proportions are accurate. In all, his When Movies Were Theater joins Douglas Gomery’s Shared Pleasures in showing, in sharp detail, just how varied and diverse American movie exhibition has been.

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

I would recommend Steven Rybin‘s anthology The Cinema of Hal Hartley: Flirting with Formalism even if I didn’t have a piece in it. For one thing, I too flirt with formalism. Hell, I nearly eloped with it. Second, my study of staging in Simple Men is pretty bare-bones compared to the rich and varied work on display in the other essays in the book. Steve has written widely on American film, both classic and contemporary (Malick, Mann). His introduction to the book ranges across a vast terrain, from models of independent film to debates about “smart cinema.”

The essays that follow offer agreeably intricate analyses of Hartley as a romantic comedy director, of “small films,” of Parker Posey as a muse, and on the Henry Fool trilogy as centered on the implications of writing. I especially appreciated the way that all the contributors (Mark L. Berrettini, Jason David Scott, Steven Rawle, Sebastian Manley, Daniel Varndell, Fernando Gabriel Pagnoni Berns, Zachary Tavlin, and Jennifer O’Meara) show how Hartley’s authorial obsessions responded to conditions of production, industry pressures, or critical reception. It’s called context, and yields a body of criticism that does honor to a director still not as fully appreciated as he deserves to be.

Another thick context, Wisconsin-revisionist style, is on display in Bradley Schauer‘s Escape Velocity: American Science Fiction Film, 1950-1982. In working on my book on 1940s cinema, I was struck by the absence of today’s dominant genres: fantasy and science fiction. SF books and magazines became widely popular in the period but, apart from cheap serials, the genre had a delayed arrival on movie screens. When it did arrive, Brad explains, it was presented not as classic space opera but something else, what he calls “topical exploitation cinema.”

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

To escape the pulp associations of Flash Gordon, SF movies traded on current scientific discoveries and headline items like flying saucers. As often happens, it took a marginal player to push a new cycle. Eagle-Lion’s Destination Moon (1950) caught the attention of big studios, which embarked on mid-budget items like When Worlds Collide and The Day the Earth Stood Still (both 1951). Brad traces the cycle’s urge for legitimacy through special effects, more sophisticated narratives, and even appeal to Scripture. These developments were shaped by broader changes in the American film industry, especially concerning budgets and program policy.

After spelling out this early history, Brad takes us through familiar titles from 2001 to Star Wars: Episode IV–A New Hope, but always fleshing out the story with new information and ideas. He shows that Kubrick gave his film prestige through art-cinema style and storytelling, while Lucas’s film gained traction by treating space-opera formulas with earnestness and respect rather than camp condescension. Brad analyzes important SF films that are often forgotten, like Logan’s Run and Rollerball. His discussion of Alien and Planet of the Apes reminds us that the current incarnations of these franchises have strayed somewhat from their original entries.

Again, the historian unearths surprises. Given the revulsion of today’s intellectuals toward Star Wars, which gets blamed for ushering in the Big Dumb Movie, it’s worth remembering that nearly all the critics praised it. Under the rubric “Fun in Space,” Newsweek‘s reviewer noted: “I loved Star Wars and so will you, unless you’re. . . oh well, I hope you’re not.” That’s sort of the way I feel about these books.

Earlier book-dedicated blog entries are here.

Designing Woman (1957): “There are three pillows stacked on each side of the sofa, and as if by chance they take up the colors of the party: red, turquoise, bluish-purple. . . . The color chord of the party becomes an end in itself, and the composition obtains a playful intrinsic value” (Christine Brinckmann, Color and Empathy, p. 48).

James Agee: Astonishing excellence: A guest post by Charles Maland

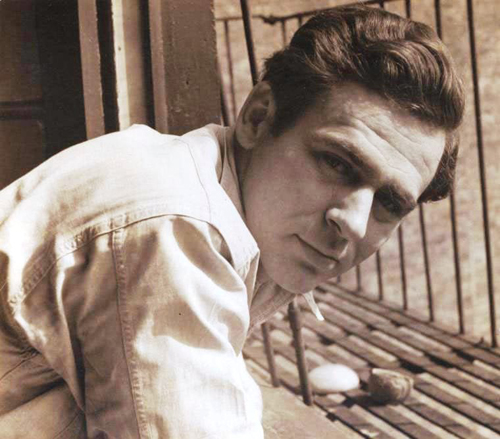

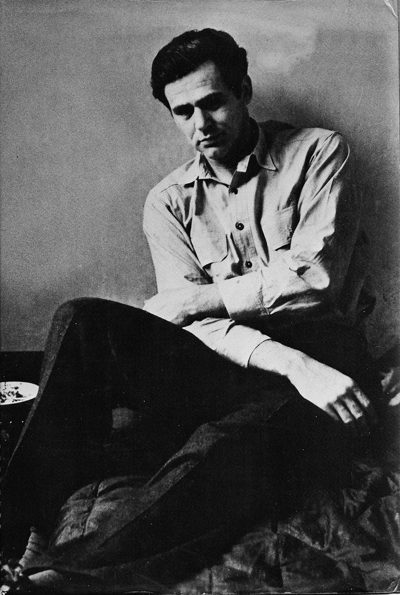

James Agee.

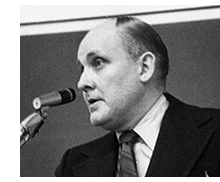

DB here: Charles Maland, a distinguished historian of American film, has just completed editing the definitive collection of James Agee’s film writings. It’s due to be published in July.

Agee changed American literature with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, and he changed film criticism with his reviews for The Nation and Time. After I wrote a 2014 blog entry on his work, I learned of Chuck’s project. Later I decided to turn the entry into a chapter of The Rhapsodes, a study of 1940s American film criticism. Naturally, I turned to Chuck for help. He was magnificently generous, steering me to sources and sharing new material he discovered. In particular, Agee’s unpublished manuscripts contain some powerful arguments and insights. Chuck’s historical introduction to the collection fills in many details of Agee’s relation to popular journalism, to the political and intellectual currents of his time, and to the Hollywood industry.

This book will be one of the most important film publications of 2017. As a warmup, we invited Chuck to write a guest entry on Agee and the process of editing the volume. We’re glad he responded, and we think you will be too.

In the summer of 1927, a precocious seventeen-year-old high school student wrote this to an older friend:

To me, the great thing about the movies is that it’s a brand new field. I don’t see how much more can be done with writing or with the stage. In fact, every kind of recognized “art” has been worked pretty nearly to the limit. Of course great things will undoubtedly be done in all of them, but, possibly excepting music, I don’t see how they can avoid being at least in part imitations. As for the movies, however, their possibilities are infinite—is, insofar as the possibilities of any art CAN be so.

Sixteen years later, British poet W.H. Auden wrote of the “astonishing excellence” of a movie column in The Nation, written by the same person, calling it “the most remarkable regular event in American journalism today.”

Auden was commenting on none other than James Agee (pronounced AY’-jee), a writer that New York Times reviewer A.O. Scott later called “the first great American movie critic.” Acknowledging that Agee didn’t “invent” movie criticism, Scott contends that he did show “what it could be as a form of journalism and a way of talking about the world.”

I concur with Scott about the importance of James Agee’s movie criticism, and for the past several years I’ve been preparing a complete edition of Agee’s movie reviews and criticism. Complete Film Criticism: Reviews, Essays, Manuscripts will appear this July from the University of Tennessee Press as Volume Five of The Collected Works of James Agee. Here I’d like to tell you a little more about who James Agee was and how he became a movie reviewer, what problems I encountered and discoveries I made in compiling the volume, and why Agee’s movie writings still deserve our attention.

Who was James Agee, and how did he become a movie reviewer?

James Agee (1909-1955) was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. In his relatively short career he was a feature writer for Fortune magazine; a book reviewer and movie reviewer for Time magazine; a movie columnist for The Nation; a co-screenwriter of, among others, The African Queen and The Night of the Hunter; and author of a volume of poetry, Permit Me Voyage (1934), an expansive social documentary book called Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and two novels, The Morning Watch (1951) and A Death in the Family (1957). The latter was published posthumously and won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1958.

The novel also draws on Agee’s autobiography. When Agee was six, his father was killed in a car accident, and the novel explores just such a situation of a young boy, growing up in the Fort Sanders neighborhood of Knoxville, and the way he and his family cope with the father’s death. In real life, following his father’s tragic death, Agee’s mother sent her son to the St. Andrew’s School, a boarding school in Sewanee, Tennessee. After a year at Knoxville High School, Agee transferred to Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. There he finished high school and published his first movie review, on F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh, which is included in the volume. He then completed his education as an English major at Harvard.

Agee loved movies from childhood. A Death in the Family includes a scene in which father and son walk from their neighborhood to go to the movies in downtown Knoxville, where they see a Charlie Chaplin short and a William S. Hart western. But he didn’t get the opportunity to review movies professionally until the 1940s. His first job as a feature writer for Henry Luce’s Fortune magazine paid the bills.

His book on Alabama sharecropper farmers in the Depression, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, started as an assignment from Fortune, but when Agee discovered that the subject far exceeded the boundaries of a feature article, he took a leave from Fortune to write the book. When it appeared in 1941, Americans were thinking about World War II and it sold only 600 copies, despite some positive reviews. The book’s reputation began to grow during the social turbulence of the 1960s, when it was reprinted and spoke to readers during that era in powerful ways. .

Following that disappointing commercial response, Agee returned to work for Time, Inc., now as a book reviewer for Time. (Volume 3 of the Collected Works, edited by Paul Ashdown, includes all of Agee’s published book reviews and non-film journalism.) While reviewing books, Agee kept alert to openings in the movie section, and he finally got his chance by reviewing The Big Street, starring Lucille Ball and Henry Fonda; the piece appeared in the September 7, 1942, issue of Time.

From then on, he remained on staff at Time as a movie reviewer until November 1948. His reviewing stint was interrupted after he wrote a powerful cover story for Time about the detonation of atomic bombs in Japan. For a few months in late 1945 and early 1946, Henry Luce put him on special assignment to write on social and political topics.

In December 1942, Agee also received an invitation from Peggy Matthews, arts editor of The Nation¸ a left-leaning journal of politics and the arts, to do a regular movie column for that audience. Agee accepted and his first contribution appeared late that month. Agee was writing about movies in two different places until his last Nation column on July 31, 1948. In between, by my best count, he reviewed 561 films in Time and 460 films in The Nation. Of that number Agee discussed 320 titles in both venues.

Agee stopped reviewing because he got the itch to write screenplays. Between 1948 and his death, he sometimes supported himself and his family as a screenwriter. His two most famous credits are on John Huston’s The African Queen (1951) and Charles Laughton’s The Night of the Hunter (1955). (Volume Four of the Collected Works, edited by Jeffrey Couchman, contains the script versions of these two films.) Partly to provide some income after he stopped reviewing but before his screenwriting career gained traction, Agee contracted with Life magazine (another Luce publication) to write extended essays on silent film comedy and John Huston. The resulting pieces, “Comedy’s Greatest Era” and “Undirectable Director,” are familiar to many readers. These pieces, along with some other individual Agee movie essays, like a review of Sunset Boulevard in Sight & Sound, also appear in the collection.

Problems and discoveries

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

The goal of this Agee collection is to provide access in one volume—for the first time—to all of Agee’s movie reviews, all of his other published articles and essays on movies, and a number of unpublished manuscripts I discovered in my research that cast light on Agee’s movie aesthetic and writing. Nearly all of Agee’s Nation reviews appeared in Agee on Film, Reviews and Essays (1958)—oddly, only his review of It’s a Wonderful Life was omitted—so compiling and editing those reviews was relatively uncomplicated.

Only a small selection of Agee’s Time reviews had appeared in Agee on Film. Because I began with what I thought was a full and accurate bibliography of all of Agee’s Time movie reviews, I thought that compiling them would be an uncomplicated task, too. I was wrong.

When he started reviewing for Time, and especially in his last months there, Agee was only one of several movie reviewers (although he was generally the primary reviewer). For the whole period he worked there, Time did not give bylines to writers. To verify what reviews Agee wrote, I enlisted the services of Bill Hooper, Time’s chief archivist. From him I learned that a copy-desk employee would handwrite in one master copy of each issue the name of the author of every article and review. These issues were then bound quarterly, and they eventually were deposited in the Time archives.

Mr. Hooper generously checked each volume against the bibliography I sent him and also responded to a number of questions that arose from the initial inquiry. The only period he was unable to verify was for the first three months of 1946: the bound volume from that period was missing. Fortunately, though, that was the time when Agee had taken an assignment as a special correspondent for social and political affairs.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

As a result of these inquiries, I discovered that thirteen of the Time reviews and articles included in Agee on Film were in fact written by other journalists. It was even more suprising to discover that all thirteen of those pieces also appeared in the Library of America edition of Agee’s writings, Film Writing and Selected Journalism (2005). Thus, of the 39 film reviews, essays, and profiles included in that volume, Mr. Hooper and I discovered that Agee had written only 26 of them. So I’m deeply indebted to Mr. Hooper. He enabled me to compile all of Agee’s film writings at Time in one place for the first time, at least as close as it is humanly possible to do.

The Agee papers, held principally in the special collections units at the University of Texas and the University of Tennessee, also contained a variety of fascinating information. I learned from financial records that Agee was well paid as a salaried employee of Time and that he was paid modestly at The Nation ($25 a column at first, later—it seems—by the word, which often amounted to less than $25). A few uncashed checks from The Nation in the archives suggest that Agee wasn’t much of a businessman. Other documents contained lists of film screenings that had been set up for Agee; they suggest that he saw a great many films, both in press screenings and regular theatre showings.

Perhaps most interesting for our purposes were a number of previously unpublished manuscripts. They included: 1) four-page typed “Movie Digest,” written in late 1935 or early 1936, containing thumbnail reviews (most with grades—A through F) of films, mostly from 1934 and 1935; 2) a scathing 1938 review of Bardèche and Brassilach’s The History of Motion Pictures that Partisan Review decided not to publish, probably because of how unrelentingly harsh it was; 3) a long letter that Agee wrote upon the request of Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish with suggestions about possible films to include in the Library of Congress film collection; and 4) some notes on movies and reviewing, probably from 1949, for a proposed Museum of Modern Art roundtable discussion of movies. All these manuscripts, including several essays or proposals for essays on René Clair and Sergei Eisenstein—both Agee favorites—are included in the collection.

Agee as movie critic

It’s hard in a short space to make generalizations about Agee’s aesthetic and why he should continue to interest us as a movie reviewer. Yet I would say he’s important for at least five reasons.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

First, grounded in the history of film, he took films seriously and thought they were capable of being great, even though most movies failed to live up to his exacting standards. Beginning his childhood movie-going about the time that Chaplin was becoming an enormous star, Agee came to embrace a pantheon of filmmakers against which he measured other work. That pantheon included silent film comics like Chaplin and Keaton; filmmakers with great ambitions who had difficulty fitting into the system in which they worked, like D.W. Griffith, Erich von Stroheim, and Sergei Eisenstein; and European masters like Murnau, Pabst, Clair, Hitchcock, Dovzhenko, and Dreyer. He also praised a variety of contemporary American filmmakers, including those as diverse as William Wyler, Preston Sturges, Val Lewton, and John Huston.

Second, his work is historically significant. He began writing just as the film industries of the United States and its Allies were trying to determine the role of movies during the world war that was raging. In his earliest reviews, Agee tended to celebrate the Allied documentaries (what he called “record” films) to the detriment of fiction movies. He was especially sensitive to a kind of poetic realism that he celebrated in Italian Neorealism (in his review of Shoeshine, for example) and in George Rouquier’s Farrebique.

Third, Agee was a magnificent and witty writer. He could write sustained, insightful essays, like his Time cover stories on Ingrid Bergman and on Laurence Olivier’s Henry V or his famous three-part defense of Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux. But he was also funny, especially when criticizing a film. Early in 1948 Agee got behind in his Nation reviews when he was hospitalized with appendicitis: to catch up he reviewed as many as 25 films in a single column, often in one sentence or two. Here are a few favorites:

On a mystery film starring Claude Rains, Agee wrote: “The Unsuspected is suspected too soon by the audience and too late by most of his fellow actors.” He disposed of an odd cinematic blend of whodunit and romance with this review: “Embraceable You is dispensable entertainment.” A John Wayne vehicle also took it on the chin: “Tycoon. Several tons of dynamite are set off in this movie; none of it under the right people.” He titled his February 14, 1948 column “Midwinter Clearance.” Perhaps my favorite was a Jeanne Crain-Dan Duryea vehicle: “You Were Meant for Me. That’s what you think.”

Fourth, Agee stands out because he had such catholic tastes. Although he was hard to please, he wrote enthusiastically and positively about a wide range of films. Agee praised European classics like Zero for Conduct, Ivan the Terrible (Part One), Day of Wrath, Children of Paradise, and Farrebique; British films like Henry V, Hamlet, Great Expectations, Odd Man Out, and Black Narcissus; a variety of American movies like The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek, Meet Me in St. Louis, The Big Sleep, The Best Years of Our Lives, Notorious, Monsieur Verdoux, and The Treasure of Sierra Madre; documentary films like Desert Victory, San Pietro, and They Were Expendable; Hollywood B films like Val Lewton’s Curse of the Cat People; the emerging Neorealist films; and dark urban dramas like Double Indemnity that later became known as film noir. Any critic who could write informatively and with enthusiasm about such a broad range of films had to possess a wide-ranging sensibility that welcomed the breadth of artistic possibilities presented by the movies of his era.

I should acknowledge here that some commentators have argued that Agee was not critical enough about really bad films and that he was too equivocal, trying to find something good to say about most of the films he reviewed. I’d respond to these claims in a couple of ways. First, it’s true that Agee was often equivocal in his reviews, but that equivocation often took the form of saying a film could have been more successful if it had done something better, but it didn’t. Another form of Agee equivocation was to say that an otherwise failed film did have some redeeming element (a song, a performance, a stylistically effective moment).

I think the fact that he would sometimes give bad films some positive gesture was partly a function of his love of the movies as an art form. I have to say I’m sympathetic to Agee here. I usually find something redeeming in almost every movie I see, and my wife regularly tells our friends that she’s the true critic in the family—they should ask her, not me, if they should see a film!

Second, I think there’s some difference between Agee’s Nation and Time reviews. He was under tighter editorial oversight at Time, and I think he was under more pressure to avoid completely lambasting a film than he was in his Nation columns. Getting a chance to read all of Agee’s Time and Nation reviews will offer readers an opportunity to think about how he wrote differently about movies for different audiences. The fact remains, however, that of the films and filmmakers he really admired, Agee showered praise on an unusually wide range of different kind of films.

Finally, as David Bordwell has observed, the publication of Agee on Film: Reviews and Essays in 1958 had a strong influence on the growth of film culture in the United States during the 1960s and after. As Bordwell put it,

There’s no knowing how many teenagers and twentysomethings read and reread that fat paperback with its blaring red cover. We wolfed it down without knowing most of the movies Agee discussed. We were held, I think, by the rolling lyricism of the sentences, the pawky humor, and the stylistic finish of certain pieces—the three-part essay on Monsieur Verdoux, the Life piece “Comedy’s Greatest Era,” the John Huston profile “Undirectable Director.” The adolescent fretfulness that put some critics off didn’t give us qualms; after all, we were unashamedly reading Hart Crane, Thomas Wolfe, and Salinger too. Some of us probably wished that we could some day write this way, and this well.

Agee on Film came along at a propitious time: European art film was beginning to flourish and a new generation of critics and reviewers—Sarris, Kauffman, Kael, Schickel, Simon, and later Ebert—engaged with this exciting new film culture. All, at one time or another, acknowledged Agee’s contributions. All, like Agee, published their reviews in book form.

For all these reasons, James Agee’s writings on the movies deserve our continued attention. I hope that by preparing a volume which contains all of Agee’s movie reviews and essays in Time and The Nation, all his other published writings on movies, and a number relevant but previously unpublished essays, I will help enable interested readers to get an accurate and fuller appreciation of Agee’s contributions to our evolving film culture.

Charles Maland is the author of Chaplin and American Culture (Princeton University Press, 1991) and the BFI classics volume on City Lights (2008). We thank him for his willingness to serve as a guest blogger.

Agee’s youthful encomium to film comes from Dwight Macdonald, “Agee & the Movies,” in Dwight Macdonald on Movies (Prentice-Hall, 1969), 3. Auden’s praise of his criticism is in “Agee on Film (Letter to the Editor),” Nation 159, no. 21 (18 November 1943): 628. A. O. Scott’s remarks come from Gerald Peary’s For the Love of the Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism (Bullfrog Films, 2009). The Bordwell quotation is in The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture (University of Chicago Press, 2016), 2-3.

Agee’s name was frequently mispronounced. At the end of a 1948 Nation column, Agee apologized for mistakenly calling Amos Vogel “Alex” in a column, then went on to say, “I apologize to Mr. Vogel and to you; and sadly join company with an aunt of mine who used to refer to Sacco and Vanetsi, and with all those who call me Aggie, Ad’ji, Adjee’, Uhjee’, and Eigh’ ggeee’.”

Our next stop: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

P.S. 1 May 2019: For more on Agee, observed from many perspectives, including Chuck Maland’s, see the commentaries at the Criterion Collection.

James Agee, portrait by Helen Levitt.

Reeling and dealing: Rescuing movies, by hook or by crook

DB here:

There have long been film collectors, and they’re central to film preservation. Some archives, notably the Cinémathèque Française and George Eastman House, were built on the private hoardings of passionate cinephiles. Filmmaking companies, both American and overseas, had little concern for saving their films until home video showed that there was perpetual life in their libraries. By then, many classics had been dumped, burned, or left to rot, and in many cases collectors came to the rescue.

In America, private collecting really took off after World War II. What happened afterward is too little known among cinephiles, but it represents an important part of film culture. A new book fills in a lot of the detail, and in a very entertaining way. It’s a big contribution to our knowledge of the afterlife of the movies.

16 + 35 = $$$$

In the late 1940s, 16mm versions of theatrical releases became widely available. For a while the studios contemplated replacing 3 5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

5mm with 16 in regular theatres, but soon the narrow gauge emerged as the format for nontheatrical screenings. Schools, churches, and colleges got war surplus 16 projectors. The Museum of Modern Art circulated classics in the format, and for newer items programmers could turn to Audio-Brandon, Janus, and other distributors.

Many of those firms dealt in foreign titles, which weren’t as attractive to most collectors—who were in love with Gollywood. For them, the floodgates had already opened when the studios licensed their pre-1948 product to television. The 1950s and 1960s were very unlike the multi-channel 24/7 TV environment of today. The networks didn’t fill the broadcast day, and many independent stations tried to support themselves apart from the nets. So everybody needed what we now call content. Our colleague Eric Hoyt has traced in detail how C & C Movietime and other entrepreneurs bought rights to classics and not-so-classics and packaged them in 16mm bundles for local TV stations. Those prints were shown throughout the day and night, interspersed with commercials cut in by staff like Barry C. Allen.

In the 1950s hundreds of copies of film classics were abroad in the land. But many of these TV prints wound up discarded and scavenged by guys (almost always guys) who wanted to show them at home. Aficionados started building their own libraries.

Collecting 35 was tougher, but it could be done. Older films were stored in labs and depots. They might wind up in Dumpsters or be smuggled out by enterprising employees. Of course showing 35 was more difficult, but it wasn’t impossible to get 35 projectors fairly cheap, and if the hobbyist was willing to make major home renovations, he (again, almost always a he) could set up a personal screening room. Some went with curtains, masking, auditorium seats, popcorn machines, and other amenities. The idea of “home theatres” for ordinary folks has its origin here.

Acquiring 16mm was gray-market but ultimately not very criminal. Because of the First Sale Doctrine, a collector was not in violation if he bought a 16 print that had already been sold (to a TV station). If I buy the new Carl Hiaasen novel Razor Girl, I can sell my copy to you because someone sold it to me. What got 16mm dealers in real trouble was their zeal to copy prints. If they got access to a nice 35, they might make a 16 reduction; or if they had a decent 16, they might pull dupes. These were definitely illegal, as if I were to scan Razor Girl and sell you a pdf.

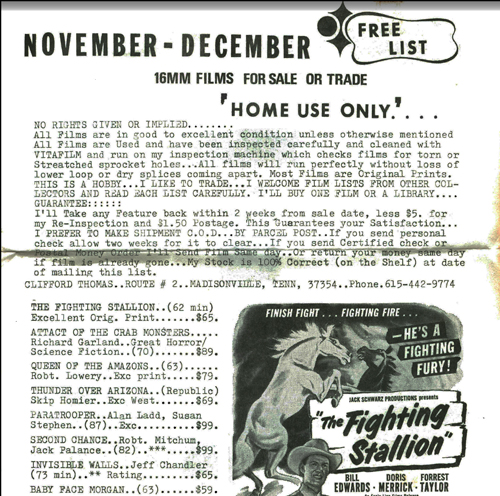

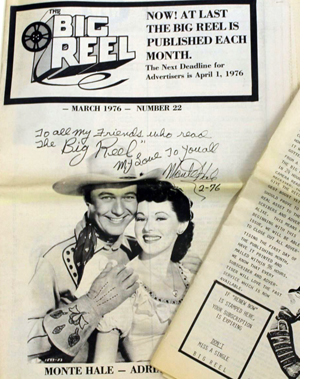

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

Mimeograph lists circulated by mail, but by the 1970s, collectors had their own periodicals, like Classic Film Collector and The Big Reel. To say that readers subscribed for the nostalgia pieces would be like saying you bought Playboy for the articles. The meat of the issues lay in the dealers’ lists, which might go on for pages. I well remember the rush to the phone after The Big Reel arrived each month. Once I called a Texas dealer who had advertised an untitled Japanese film. He was puzzled by its Irish name: The Life of O’Hara.

With some exceptions, 35 prints weren’t originally sold, only rented, and so possession of one suggested, to suspicious minds, big-time theft. Actually, most collectors’ prints had been junked, and you can argue that once something is tossed out, it’s the American Way to scavenge and recycle it.

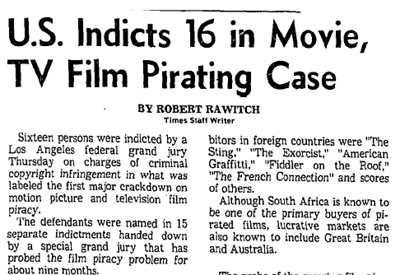

Beyond the domestic collectors’ market, there was money to be made with 35 prints. American films didn’t circulate much in Cuba, South Africa, parts of Asia, and Eastern Europe, so there was an international demand for bootleg copies, and some dealers were happy to meet it. I lost out on a collection of Hong Kong films that was bought by an Indian dealer who intended to circulate them at home. I always think of that episode when I see the almost inevitable kung-fu fight in an Indian action movie.

The sale of 35 boomed because of another factor. With the rise of the blockbuster mentality in 1970s-1980s Hollywood, the nation was awash in theatrical prints. Then as now, a film might open on thousands of multiplex screens, play a few weeks, and be done. The studio would keep a few of those prints, but the rest would have to be disposed of. Salvage companies were contracted to destroy them, but—human nature being what it is—often some copies slipped out and into eager hands.

Films stored in laboratories or warehouses had a habit of disappearing as well, and prints shipped to theatres might be waylaid. I remember booking Blue Velvet and learning that the copy had disappeared in transit. The fact that prints were labeled with their titles printed in large letters probably didn’t help keep them safe. I was always startled to see the casual ways in which prints were handled. On Thursday midnights I’d leave a screening at one local theatre and see, neatly lined up on the sidewalk, shipping cases bearing the titles of films that had played there in recent weeks, waiting for a UPS pickup the next morning. After a theatrical run, exhibitors cared as little for prints as producers and distributors did.

Many collectors favored older titles, but others were as susceptible to blockbuster mania as general audiences. Star Wars, Jaws, The Godfather, and all the other top hits became as sought-after as Casablanca and Snow White. Collectors still boast of having multitrack, IB-Tech copies of 1970s and 1980s franchise pictures.

Enter the Feds

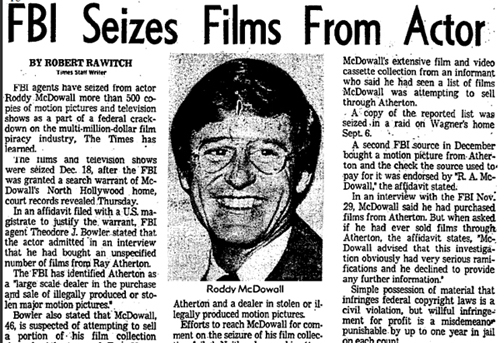

Los Angeles Times (17 January 1975), B1.

I’ve moved from describing the collectors’ market to describing the dealers’ market. That’s because they were almost one and the same. Collectors needed dealers to help find the rarities they yearned for; collectors started to deal to support their habit; and dealers, whether collectors or not, found that they could make money acquiring and selling movies. Demand and supply, in solid capitalist fashion, created an underworld traffic in prints.

The studios didn’t take this lying down. With the aid of the FBI, they pursued collectors, pressuring them to snitch on their suppliers and fellow addicts. Former child star Roddy McDowall, an avid collector, was the most visible target of these maneuvers. I well remember the chill that passed through the collector community at the news of the Feds’ raid on his house, which turned up hundreds of prints and videos. McDowall, who could probably have won a legal case, gave up many of his contacts. Charges against him were dismissed, but the U.S. Attorney pursuing the case warned that the activities of film collectors (said to number 65,000) “could constitute serious violations of both state and federal law.”

Most collectors flew under the radar, though. Although McDowall’s collection was mostly 16mm, the studios turned a blind eye to 16mm collectors. Famously, William K. Everson helped studios uncover lost films (e.g., obscure Fords and Stroheims) and as payment received 16mm copies of his discoveries. Collectors like Bill, who accumulated several thousand prints, shared their libraries with archives and film schools; at NYU, Bill taught from his collection for many years.

Home video didn’t destroy this underworld right away. The first video systems were of such poor quality that they couldn’t compete with 16mm projection, let alone 35. However, as formats improved in the 1990s, more and more collectors turned to video. Why thread up a battered copy of an MGM musical when a pretty nice DVD could just be popped into your player? With the arrival of Blu-ray, which can look very impressive projected in theatrical conditions, 35 began to be seen as more and more a retro hobby. And your average hobbyist was discovering that he (still almost certainly a he) was aging. Or dying.

The studios mostly lost interest in film-based piracy, once video presented a threat on a much bigger scale. Duplicating VHS and laserdisc, always imperfect, was followed by the cloning of perfect copies of DVDs. Now, of course, the main arena is the Net, where film piracy via BitTorrent has exploded to a level the old-timers couldn’t imagine. Back in the 60s, there were very few film collectors. Now, thanks to digital convergence and massive hard drives, everybody is a film collector—not only he’s.

Boom and busts

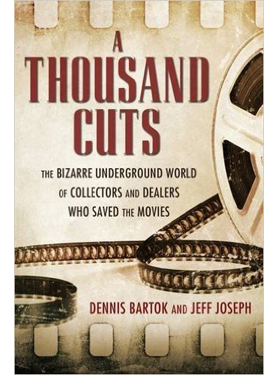

This is the world chronicled, with affection, humor, gossipy detail, and a pang of melancholy, in Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph’s A Thousand Cuts. Dennis has been head of programming for the American Cinematheque, and he currently heads the distribution company Cinelicious Pics. Jeff was one of the top film dealers in the country; at its peak, his company SabuCat sold about 1,000 prints per month. In the wake of the McDowall bust, Jeff became the only film dealer to serve time for selling prints. Jeff is now a distinguished archivist, conserving 3-D prints and, most recently, rare Laurel and Hardy movies.

The book lives up to its subtitle: The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies. Through interviews, documents, and vast knowledge of the world of film dealing, Bartok and Joseph have given us an invaluable survey of a wondrous land. It’s as gripping, and sometimes as hallucinatory, as any Forties B noir.

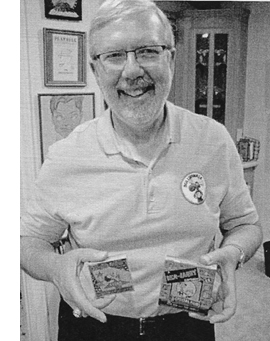

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Start with the cast of characters. Hugh Hefner, it turns out, was a huge collector, and not just of erotica. Probably today’s most visible collectors are Robert Osborne, of Turner Classic Movies, and the genial Leonard Maltin (right), who has lived in many worlds—fandom, mainstream publishing (thorough books surveying aspects of film history), and mass media (TCM, Entertainment Tonight, etc.). His obsession: shorts and cartoons. Men with an appetite for features include director Joe Dante and producer Jon Davison, whose collections continue to grow.

Once we leave behind the celebrities, things take a more exotic turn. There’s Evan H. Foreman, the first collector targeted by the studios, a tough customer who fought for the right to sell prints and was called to testify before a Senate committee. There’s Ken Kramer, proprietor of The Clip Joint, a Burbank archive and screening facility decorated with posters and Christmas lights. There’s Tony Turano, who claimed for years that he was the baby in the bulrushes in The Ten Commandments. Tony kept his apartment heavily curtained, the better to preserve Claudette Colbert’s headdress and robe from Cleopatra (1934). Paul Rayton, projectionist extraordinaire, stores the cans for his rare Oklahoma! print in the back seat of his car. Not the film–it went vinegar long ago. Just the cans.

There’s Al Beardsley, uniformly considered untrustworthy, perhaps because he simply picked up a 70mm print of Lawrence of Arabia posing as a delivery courier and immediately sold it to a collector. Beardsley gave up film dealing for sports memorabilia, and became a participant in the O. J. Simpson throwdown in Vegas. As Beardsley recalls his encounter with one Thomas Riccio, who had set up the O. J. meet: “I had a drink and, I believe, a hamburger that Riccio paid for. He feeds you before he screws you.” O. J. was more direct: “Motherfucker, you think you can steal my shit and sell it?” Yes, firearms were involved.

This is as wild and crazy as any nerd culture can be. Like collectors of comic books and LPs, film mavens are clannish and wily, generous and secretive, boastful and yet somewhat innocent. These guys can’t be considered Geek Chic; they retain an unselfconscious love for what moved them in their youth. They live in the Adolescent Window, as we all do, but they don’t pretend to have become hip. And they run risks that other collectors don’t. A book or record collector runs no risk of arrest. But should a film collector offer a rarity to an archive? Will the studio claim it and bury it? Will the law get involved? Paranoia strikes deep, and justifiably.

Some of the tales are painfully funny, some just painful. This is the sort of book that contains sentences like:

The two were briefly partners as film dealers in the early 1970s, until Ken’s then-wife Lauren left him to marry Jeff, shortly after they were discovered having an affair at the 3rd Annual Witchcraft and Sorcery Convention.

Turano, wheelchair bound, had a habit of bursting into showtunes at the top of his voice. Tom Dunnahoo, of Thunderbird films, “routinely passed out on the floor of his film lab drunk on Drambuie.” A dealer takes pride in the fact that at his trial, the expert on the stand couldn’t tell his dupe of Paper Moon from the original. Another bit of dialogue:

“You remember I had a beet-red print of Giant? Well, Louie Federici ran it and borrowed a beautiful IB print of Giant. Afterward he sent it back to Warners, and you know what they got? A beet red print,” he says, face lighting up.

“You swapped it out?” Jeff asks.

“I did. And later I traded it to you for Singin’ in the Rain. How about that, huh?”

Nearly every page of my copy boasts my penciled ! in the margin.

Saving the movies

Jeff Joseph and Dennis Bartok, Cinecon 2016.

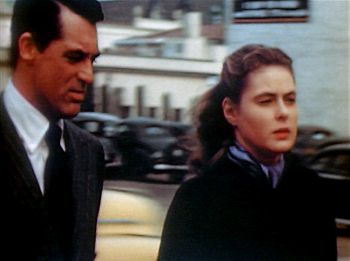

The book stresses that collectors functioned as preservationists. Just as in the early days of archives, they have saved films major and minor from destruction. Just last week, we learned that a collection of 9.5mm has added more footage to a partially surviving Ozu film, A Straightforward Boy. Famously, missing King Kong footage was discovered by a collector. . . and given, not sold, back to the studio. Tony Turano found a missing Fred Astaire number from Second Chorus in Hermes Pan’s closet. Jeff Joseph preserved color behind-the-scenes footage of Animal Crackers and found remarkable home-movie Kodachrome footage of Hitchcock, Bergman, and Grant out for a walk during the shooting of Notorious (surmounting today’s entry). Mike Hyatt has devoted his life to cleaning up The Day of the Triffids. Using a jeweler’s loupe and a needle, across many years, he flicked over 20,000 bits of dirt out of the camera negative.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Every collector I’ve known has welcomed sincere interest in their holdings. In pre-video days, Bill Everson (right), unbelievably, loaned prints to undergrads for their papers. Kristin and I spent many nights at friends’ homes screening rare silents and unusual items, like a full-frame print of North by Northwest that showed the edges of the Mount Rushmore backdrop. Nearly every chapter of A Thousand Cuts recalls nights when the collectors would screen their rarities. Cutthroat they might be in dealing, they were often eager to share their treasures with those who’d appreciate them.

Most of the stories in the book come from the West Coast, as you’d expect. Other regions have their own lore and characters. The East Coast was a lively scene, centering on Manhattan’s Theodore Huff Film Society (duly noted in A Thousand Cuts) and Bill Everson’s screenings at the New School and elsewhere. Scorsese is, of course, a famous collector. Until this last year hard-core fans of old films gathered at Syracuse’s fine Cinefest. The Midwest had its own center of film trade, Festival Films in Minneapolis, now a source of public-domain items. The screening-and-dealing gathering Cinevent, in Columbus, Ohio, is entering its 49th year.

There were colorful personalities hereabouts too, including a Milwaukee collector with a stupendous array of original Hitchcocks from the 1950s. Another Wisconsin collector, Al Dettlaff, discovered and jealously guarded Edison’s 1910 version of Frankenstein. I met a collector in remote Minnesota who had converted his garage for 35mm screening both indoors and outdoors. He could aim his projectors to shoot out onto the back yard for neighborhood shows (a popular pastime for collectors). During the snowbound winters, he could swivel the machines to shoot through the kitchen to the living room. I asked how his wife felt about sawing holes in the walls. He said: “She’s fine with it. She knows I can get a new wife a hell of a lot easier than an IB Tech of Bambi.”

Dennis and Jeff are to be thanked for recording precious information about a phase of American film culture that has been neglected. They’re continuing the effort with a clip show on 23 September at the American Cinematheque’s Egyptian Theatre. It will include many items mentioned here, as well as a Bela Lugosi interview from 1931.

The collecting adventure is not quite over. The book profiles passionate younger aficionados, some of whom keep the energy going online. Still, as someone who has relinquished his passion for owning film on film and is happy that archives are taking over the task, I’m afraid it’s evident that the curtain is coming down. Without collectors, who will scavenge all the films not likely to be transferred to digital formats? The book ends with a list of six interviewees who died during writing and publication. And in the podcast below, Jeff glumly notes that studios are still junking prints.

Thanks to Jeff Joseph for illustrations. The Len Maltin picture is by Dennis Bartok. For a fascinating podcast that gives the authors a chance to expand on many aspects of A Thousand Cuts, check The Projection Booth. There’s a shorter streaming interview at KPCC radio.

Typical collector story: How did William K. Everson acquire his K? He told us that the first movie he remembered seeing was by William K. Howard, so Bill borrowed the middle initial. Another: We did our bit. After seeing an ad in The Big Reel for a hand-tinted Méliès print, we alerted Paolo Cherchi Usai, then at Eastman House. It turned out to be one of the lost Méliès titles.

Thanks to Haden Guest for tipping me to the Ozu rediscovery. I talk about how piracy created a classic here. For more on 16mm collecting and showing, go here and here. In this entry we cover Joe Dante’s remarkable visit to Madison and his presentation of The Movie Orgy, one result of his insatiable collecting appetites.

P.S. 14 September 2016: I should have mentioned another collector committed to preserving 3D films. Since 1980 Bob Furmanek has been building a large 3D archive, a project that is still ongoing. The history of his work is traced on his site.

P.S. 15 September 2016: Thanks to Christoph Michel for correcting a howler that out of shame I shall not name.

Animal Crackers, Multicolor on-set record (1930). Courtesy Jeff Joseph.

INDIGNATION: Novel into film, novelistic film

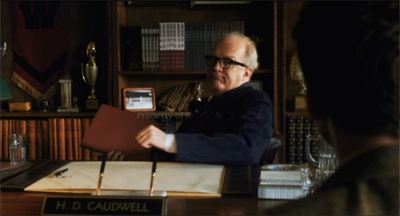

Indignation (2016).

DB here:

As I finish my book on 1940s Hollywood storytelling, I see that period’s influence all over the place. (Actually, that’s part of the book’s point.) One thing that filmmakers did back then, I think, is make cinema more “novelistic.” It’s not just that they took stories from novels, though they certainly did. They also made much greater use of storytelling devices that had become common in literature both high and low.

Many of these techniques I’ve talked about in other entries. There were, of course, flashbacks—not new to the Forties, but now much more frequent than in the Thirties. There was also the rise of voice-over commentary, like the narrating voice of fiction. It might be the voice of an objective narrator, as in Naked City (1947). Or it might be the voice of a character, either telling the tale to another character, or recalling events purely in his or her mind.

Other types of subjectivity came forward too, such as dreams, daydreams, and hallucinations. Filmmakers of the 1930s were inclined to tell their stories objectively, through concrete behavior. But thanks to imported and revised literary strategies, many Forties films gain a greater density and interiority. Compare, for example, the 1931 Waterloo Bridge with the 1940 one.

One thesis of my book is that filmmakers of the Forties consolidated these strategies in a way that became central to modern movie storytelling. That seemed to me to be confirmed when I saw James Schamus’s directorial debut, Indignation, now or soon playing at a theatre near you. Because of his skill as a screenwriter, I expected an intelligent adaptation of Philip Roth’s novel, but I also hoped to learn more about the expressive resources of contemporary cinema. I wasn’t disappointed.

Indignation’s core story involves Marcus Messner, studious son of a New Jersey butcher who goes off to a Midwestern college. Stuffed with ideas and ambitions, Marcus is intellectually worldly but socially and sexually naïve. If he weren’t in college, he’d be drafted to fight in the Korean War. Instead of fitting smoothly into academic life, he finds himself confused by Olivia Hutton’s calculated sexuality. In addition he struggles with an overprotective father and the puritanical, hamfistedly Christian, regimen of 1951 campus life.

To talk about what I find exciting and instructive in the film, I have to presume you’ve seen it. So what follows is filled with spoilers.

Sticking to one causal line

Like the book, the film is an exercise in restricted point of view. That involves not simply the voice-over commentary that weaves in and out. (In a film, that technique doesn’t guarantee restriction the way first-person narration would in a novel. Movies can be more promiscuous in breaking with what one character thinks and knows.) And the restriction isn’t wholly a matter of a subjective plunge either, though we do get Marcus’s dreams and fantasies and some fragmentary flashbacks.

No, what makes Indignation intriguingly “novelistic” is a matter of attachment. We’re simply with Marcus through almost the entirety of the movie. We know only as much as he knows. This means that we learn about certain things when he does. His father’s breakdown back home is conveyed through phone calls. At the climax, his mother’s visit to him in the hospital reveals that she’s considering divorce. An alternative narrative strategy would be to shift from scenes with Marcus to scenes elsewhere, say back home in New Jersey or in Olivia’s dorm. This “omniscient” option is more common throughout American film history; we see it in the crosscutting between CIA malefactors and poor David Webb in Jason Bourne.

Restricted narration isn’t the only way to generate mystery, but it’s a reliable one. By attaching us to Marcus’ range of knowledge, Indignation creates mysteries, chiefly around Olivia. What has made her behave as she does? She never offers a full explanation, but in some scenes she tells more about her parents and in a crucial confession she confesses her alcoholism, a suicide attempt, and a period in treatment.

During this confession, Schamus finesses the showing/ telling problem in an intriguing way. There are good reasons, I’ve suggested before, to let such monologues play out in the space and time of the scene. Telling is sometimes more vivid than showing. But Schamus has chosen to show as well as tell, by providing quick flashback illustrations of what Olivia recounts to Marcus.

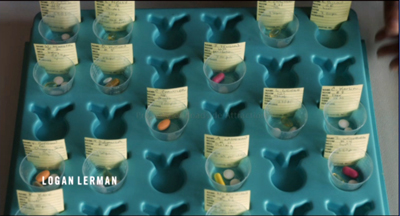

What interests me is that these images from the past have an in-between status. They’re neither straightforward and neutral, nor Olivia’s own viewpoint, nor exactly Marcus’s imagined version of what she’s telling him. For instance, the straight-down, somewhat diagrammatic and clinical framing of some of them calls to mind the film’s first shot, also associated with Olivia’s health: the pill case in the care facility.

Likewise, the shot of Olivia in a straitjacket, framed off-center in a way few other isolated long shots in the film are, has an abstract quality that suggests an image lying somewhere between her memory and Marcus’s imagining of her situation—without making it wholly subjective. (In the early 1950s, it’s plausible she was indeed treated this way.)

At the climax, we get even less information about Olivia’s situation. Before Marcus can break off with her, she simply vanishes. Marcus will never find out what became of her. For him, if not for us, the mystery is permanent.

Not that he doesn’t try to communicate. This is one role of the voice-over in which he muses on his past and, more ambitiously, on the role of cause and effect in life. As a follower of Bertrand Russell, he’s evidently pondering Russell’s idea of “causal lines.” Ironically, though, Russell’s inferential model of causality doesn’t help Marcus figure out what happened to Olivia.

But from where is Marcus speaking? Quite likely, from the Afterlife.

Dead narrators drift through 1940s cinema. Philip Roth was ten when The Human Comedy (1943) featured a deceased father returning to his small-town family, and eleven when The Seventh Cross (1944) gave us an executed prison-camp escapee who shadows one of his mates. So Indignation, set in the year after Sunset Boulevard (1950), seems perfectly in keeping with this trend. But these other films announce the voice-over’s posthumous status right away. Schamus does something a bit different.

In the source novel, Roth lets Marcus suggest that he’s dead about a quarter of the way through. Schamus’s screenplay drops hints that are, I think, fully noticeable only in retrospect. He creates a surprise that in turn motivates one of the two frames that surround the 1951 story action.

The front end of the inner frame is a brief combat skirmish in South Korea. A GI is pursued into a dark, nondescript building by a North Korean soldier. The action is difficult to discern, but we can see that the Korean is shot. Did the GI escape? The combat scene will be partially replayed near the film’s end, closing the frame the first one opened. The GI will be revealed as Marcus, who is dying from a bayonet thrust.

This isn’t merely a trick. In the 1940s filmmakers realized that some stories, if told chronologically, begin in rather slow and uninvolving fashion. But starting at a crisis late in the story’s causal chain, and then flashing back to what led up to it, can arrest our attention. Think of what The Big Clock (1948) would be like if we started not with the hero dodging around corridors trying to elude the police, but with his mundane office routine earlier that morning. So instead of starting with Greenberg’s funeral, Indignation grabs us with a brief and enigmatic piece of life-or-death action.

1940s frames are more explicit about the framing situation than the combat incident in Indignation. Yet Schamus evidently didn’t want to show Marcus lying there dying and reflecting on his life and leading into the film as a whole: too on-the-nose, and perhaps too obviously fatalistic. The shift to the Jonah Greenberg funeral frees the story action from what Henry James once called “weak specificity.”

There’s also the possibility that Marcus survives; we don’t see him die, even in the finale of the skirmish. The fact that the film can equivocate about whether our narrator is alive or dead emerges as a fresh treatment of the Afterlifer convention.

By raising the possibility of a dead narrator early on, Roth may make us view Marcus’s actions with more detachment, sub specie aeternitatis. The film version, I think, gets us more emotionally invested in Marcus, and this makes the eventual possibility (for me, the likelihood) that he has died more wrenching.

More than Marcus

Even in the enframed 1951 story action, our attachment to Marcus’s range of knowledge isn’t complete. For one thing, there are ellipses—most notably, the crucial scene in which he asks Olivia on their first date. There are also moments in which we run ahead of his awareness. When his mother meets Olivia, Schamus has controlled his actors’ eyelines so that even in a two-shot we’re not looking at the hero but rather at Mrs. Messner, who spots the girl’s wrist scar.

This is sharp visual storytelling. Marcus is unaware of his mother’s observation, but we’re prepared for her later admonition that he’s getting involved with a woman who will bring him misery. (Marcus: “She slit one wrist.” Mrs. M.: “One is enough. We have only two, and one is too much.”)

We’re also a beat ahead of Marcus in one neat shot that shows him stepping onto the quad as he’s facing expulsion. We see his future before he does; the marching ROTC students in the background catch our notice before a rack-focus brings him up to speed.

We’re also invited to see parallels that pry us a bit away from Marcus’s immediate experience. At two crucial moments, the adults trying to intimidate him—Dean Caudwell and his mother—come around behind him to keep wheedling.

The know-it-all debater has a chance when fighting face to face, but he crumbles when authority steers from behind.

Above all, our attachment to Marcus is qualified by a second frame, the one that wraps the whole fiction. This is wholly Schamus’s invention—a nested structure of the sort characteristic of 1940s films. At the very beginning and end of Indignation, we see an elderly Olivia in a care facility staring at the wallpaper dotted with a pattern of flowers in a water carafe. The image (also on a skirt she wears in the college portion) harks back to her impromptu bouquet for Marcus in the hospital.

But of course we’re inclined to ask: How likely is it that such a pattern would be used on wallpaper, and would it so neatly coincide with an item in Olivia’s past? We could then ask whether the pattern is in her imagination. (There is a sort of blurring and refocusing on the pattern, suggesting her optical viewpoint.) And since her scenes in the facility bookend the entire film—the Korean War frame, which in turn encloses the Winesburg College days—we might ask whether everything we’ve seen isn’t a product of her fantasy.

I’m not inclined to say that she has made up the whole movie. Indeed, if the wallpaper pattern is her projection, it would have to be so not just in her optical POV but also in the wider shot of her, the first image we get of her as an old woman.

Maybe this room, Caligari-like, is a total projection of her memory? More likely, it’s objectively there but triggers her recollection of Marcus. I’m still uncertain, but it does seem that giving Olivia the ultimate framing for the tale via their shared moment with the flowers suggests that Marcus, who at the end of his last monologue is calling out to her, has somehow finally made contact.

In any event, a purely formal cadence, completing the ABCBA structure and revisiting an ambivalent motif in the film, can balance, in aesthetic terms, the absence of answers to questions posed in the story world. This appeal to geometrical architecture and symmetrical construction is, since Henry James, another novelistic convention: art’s order can frame, if not completely account for, the disorder of life as it’s lived.

Goliath wins

The sequence that has everybody talking is the sixteen-minute two-hander between Marcus and Dean Caudwell. It’s in the book, but Schamus and his players have brought to life the clash between idealism and suave, well-practiced bullying.

Straddling the film’s midpoint, this scene enacts the old proverb. “Old age and treachery trumps youth and skill.” It starts with a simple bureaucratic issue: Marcus’s transfer out of the dorm to a shabby, solitary room. This incident leads Dean Caudwell to charge him with stubbornness, lack of compromise, secrecy about his Jewish identity, friction with his family, intellectual arrogance, and cowardice. The whole cascade is punctuated by the Dean’s intermittent requests to stop calling him “sir.” It’s a verbal boxing match with Marcus gamely fighting on after quite a few low blows. Nobody who read Why I Am Not a Christian in their youth (as I did) can fail to be roused to self-righteous fury by Caudwell’s calm, close-minded innuendo.

Still, in such duels dialogue and performance need to be orchestrated with framing and cutting. Steve McQueen’s solution in Hunger (2008) is the use of a sixteen-minute profile long-shot, followed by a cut in to Bobby Sands’ hand picking up his cigarettes, and then a very tight close-up of his face as he continues speaking.

The interruption of the long take gives special prominence to a shift in the conversation, when Sands recalls his childhood. Later shots revert to shorter shot/ reverse-shot exchanges.

So framing and cutting can articulate phases of the drama. This Schamus does very carefully in the Indignation scene. To abbreviate:

Phase 1: More or less businesslike and polite: Why couldn’t Marcus compromise with his roommate? 180-degree cuts, with framing favoring Dean Caudwell–centered and dominating Marcus.

Phase 2: Caudwell gets personal. Why didn’t Marcus identify his father as a kosher butcher? Eventually he’ll accuse Marcus of intolerance. Here a fairly lengthy profile shot reminiscent of Hunger gives way to shot/ reverse-shot.

Phase 3: More personal probing: How does Marcus get along with his family? What about his sex life? And religion? After more shot/reverse shot, Marcus, sweating and feeling sick, rises to defend himself in close-up. That calls forth the closest shot yet of Caudwell.

Phase 5: Caudwell says Marcus’ sophistry will make him a fine lawyer. He comes to stand behind Marcus, putting his hands on his shoulders. Then he sits beside him, to drill in still more. Marcus, shaky, asks to leave.

Phase 6: At the door: Marcus is feeling sick. The dean asks if he’d like to play baseball. Finally Markus collapses and starts vomiting.

Schamus has saved shot/ reverse shot for when the scene heats up, and saved his close-ups for when things reach a pitch. This reminds us, as the Hunger scene does, that if you’re going to use a standard technique, hold off until it will do the most good. Ditto for the low angle on Marcus throwing up; that comes with more force if we haven’t already had low angles before. Schamus has let his cutting and shot scales amp up the drama without the crushing emphasis supplied by so many directors. Yes, I’m thinking of the barrage of close-ups in every dialogue scene of Jason Bourne. (Thanks to Paul Greengrass, Tommy Lee Jones’s facial contours qualify for Federal Drought Relief funds.)

I think that Indignation will be studied for years as an intelligent adaptation of Roth’s novel, but it ought also to be admired as a well-crafted work in its own right. It finds fresh ways of molding fiction techniques to the demands of cinema in general and Hollywood tradition in particular. And the film reminds us—or me, at least—how much contemporary filmmaking owes to the consolidation of “novelistic cinema” seventy years ago.

Thanks to James Schamus, Gustavo Rosa, and Lauren Hynnek for information and assistance, . For more on James’s career, see our entry.

Students of literature might find another novelistic analogy in Olivia’s explanation of her suicide attempt. It somewhat resembles the technique of free indirect discourse, when the third-person authorial voice adopts the language and syntax of the character’s thought. Roth employs this in the third-person tailpiece of his novel. Instead of “If only I hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for me at chapel!” we get “If only he hadn’t let Cottler hire Ziegler to proxy for him at chapel!” Is it possible to have a cinematic equivalent: an objective vision that is pervaded by the character’s state of mind? Pasolini thought so, and suggested Red Desert, Before the Revolution, and Godard’s films as examples of it. Perhaps this flashback sequence counts as a case of Pasolini’s “free indirect subjective.”

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I briefly discuss the resurgence of 1940s storytelling strategies in recent studio cinema (pp. 72, 83). A general discussion of my interest in 1940s narrative is here. Elsewhere I make the case for Tarantino reviving 40s formats; for the importance of Afterlifers in the Forties; for nested narratives like that of Indignation; for replays that provide new information; and for the blurring of subjective and objective in Nightmare Alley.

For more on novelistic strategies in film, see “Watching a movie, page by page” and Kristin’s entries on the Hobbit films, all linked here.

Indignation.