Archive for the 'People we like' Category

Picturing performance: THEATRE TO CINEMA comes to the Net

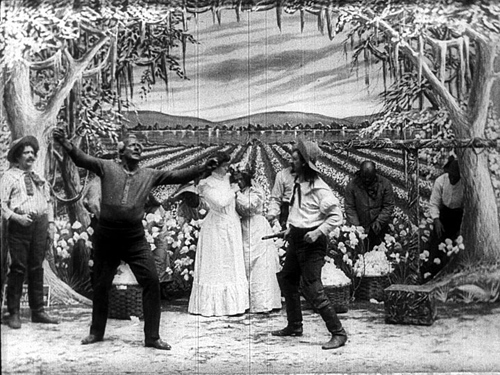

Ma l’amor mio non muore! (aka Love Everlasting, 1913). Lyda Borelli.

DB here:

The core of cinematic expression is editing. Since the 1920s, that view has been part of the lore of film aesthetics. Editing, people said, is what distinguishes film from other media. After all, the single shot is both a picture (like a painting) and a dramatization (like a scene in a stage play). But put one shot with another and you’ve got a technique impossible to parallel in other media.

But if we look closely, we find that the film image is as “uniquely cinematic” as editing. After all, a film is an image, but it’s a moving image, which is sharply different from a painting. And although a shot is a dramatization, it’s two-dimensional (unlike a stage scene) and the space it captures is quite different from that of the theatre. Anyhow, maybe editing isn’t uniquely cinematic. Comic strips juxtapose discrete images, and some forms of theatre (such as pageants, or turntable stages) can shift rapidly between scenes. Once we start to compare adjacent media, we find many overlaps in their expressive resources.

Why did early film theorists make editing so important? They were often defending the view that film was a new art, in the teeth of opponents who claimed that it was simply photographed theatre. Accordingly, film’s defenders looked for features of films that seemed to have no counterpart in theatre, such as the close-up and, more pervasively, editing.

Since then, we’ve come a long way in our understanding of film’s artistic capabilities. Filmmakers, particularly those in the early sound era (Renoir, Ophuls, Dreyer, Mizoguchi), showed the expressive power of the single shot. This tendency was amplified in the 1950s and 1960s with Antonioni, Jancso, Andy Warhol, and many other directors. Now nobody blinks if a filmmaker like Hou or Yang presents a lengthy, unedited sequence.

Informed by what’s possible in the single shot, we ought to find the earliest filmmakers using the resources of staging, composition, and performance in felicitous ways. So we do. Once we foreswear the cult of the cut, we can see that early cinema made extensive use of cinematography and mise-en-scene for powerful artistic effects. And conceding that, we suddenly find ourselves back in the lap of the other arts–painting and theatre.

Living pictures

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

No one has done more to clarify the debt of early cinema to theatre than our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. In the spirit of Wisconsin Revisionism, they have embraced early film’s stagy side. They’ve taught us to appreciate the ways in which dramaturgy and performance of 1910s cinema derive, in unexpected ways, from the theatre. Their trailblazing book Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film (Oxford, 1997) showed how to appreciate early films in a whole new way: by seeing them as borrowing and modifying conventions of the stage. What may look artificial or backward to us were actually tools of subtle, supple expression.

Here’s the authors’ statement of the book’s argument:

While previous accounts of the relationship between cinema and theatre have tended to assume that early filmmakers had to break away from the stage in order to establish a specific aesthetic for the new medium, Theatre to Cinema argues that the cinema turned to the pictorial, spectacular tradition of the theatre in the 1910s to establish a model for feature filmmaking. The book traces this influence in the adaptation and transformation of the theatrical tableau, acting styles, and staging techniques, examining such films as Caserini’s Ma ľamor mio non muore!, Tourneur’s Alias Jimmy Valentine and The Whip, Sjöström’s Ingmarssönerna, and various adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

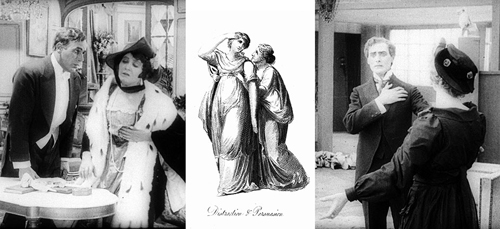

The twist here is that turn-of-the-century artistic culture had already blurred the boundaries between theatre and painting. Painters drew upon the stock gestures and poses of the stage, while plays presented vivid visual effects that were indebted to painting. The term “tableau,” referring at once to a picture and a poised stage image, captures this convergence between the media. That’s why Ben and Lea refer to “stage pictorialism” as the nexus of their inquiry.

Thanks to their research, we can see the unbroken long- or medium-shot of early features as permitting a complex choreography of facial expressions and bodily attitudes, which were in turn indebted to both pictorial and dramatic traditions. Standard gestures were summoned up and reworked to suit dramatic situations–as, for example, clutching.

When we do find editing or camera movements in these films, they’re often at the service of the performance style. Ben and Lea powerfully make the case that the expressive human body was at the center of storytelling in the first years of silent cinema. (If nothing else, the book is an in-depth analysis of diva acting from the likes of Lyda Borelli and Asta Nielsen.) By studying the history of theatre, we can learn to appreciate aspects of acting that might otherwise escape our notice.

Theatre to cinema to pixels

Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Slavery Days (Edison, 1903).

How, you’re asking, can you gain access to the ideas and information and images in this fine book? It’s now criminally easy.

When Theatre to Cinema was published, all the illustrations came from 35mm film prints. Those originals were gorgeous. But in some printings of the book the stills came out badly, and when the book moved to print-on-demand status, the images suffered even more. A couple years ago, Ben and Lea rescued their book and took the opportunity to make a digital version. It’s unrevised, largely because updating a twenty-year-old volume would be a major overhaul, but errors have been corrected and–very important–the stills have been much improved.

Start here, with the introduction to the project. You can download the new edition of the whole book, section by section, here.

Naturally, Kristin and I are sympathetic to this effort. Since we started our website back in 2000, we have explored ways to amplify and extend our ideas by means of the web. In the beginning, and inspired by Philip Steadman’s Net-based supplements to his excellent Vermeer’s Camera, I added material that would enhance arguments I made in Figures Traced in Light. Then we set up our blog, now in its tenth year. Over the same period, we posted web essays, as you can see in serried ranks page left. We also used the site to preserve older material, such as film analyses dropped from editions of Film Art: An Introduction and even entire books, as in Kristin’s 1985 monograph Exporting Entertainment. We’ve mounted video lectures. And we’ve produced a new edition of an older book, Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and original e-books such as Pandora’s Digital Box and Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages.

Ben and Lea have found another way to expand a book’s Web life. They have put Theatre to Cinema at the heart of a digital collection sponsored by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Libraries. Here’s what they offer:

In this collection, we try to supplement the description and illustration that accompanied the book in a way that makes it easier for readers to appropriate our work—both to understand it, and to make use of it in research and teaching. What were illustrations in the pages of the book are also presented here as better-quality downloadable images.

For example, you can pick a still, find its mates in a single display, and blow it up for scrutiny. If you want import it into your own files, you may choose among four different file sizes.

The provenance of each still is provided, so scholars can compare prints from different sources. In addition, there’s a master index of the visual documentation, in sequential groupings across the book.

Finally, Ben and Lea plan to add video extracts from some of the films they discuss. When those go up, we’ll announce it here.

Every admirer of silent film, and everyone who studies the interrelationship of the arts, should read this book. Hard copies are still being sold online, but they’re apt to be versions with weakly reproduced stills. Get one if you want, because a book is a good object to have in hand. In addition, for free, you can own a beautiful, searchable edition with superb stills. I think you need both.

The digital collections set up by UW Libraries are breathtaking. Check them out here.

Some entries on our site intersect with Ben and Lea’s research. See the category Tableau staging.

Weisse Rosen (White Roses, 1915). Asta Nielsen.

Manhattan wrapup: RHAPSODES and more

Aliza Ma and RZA at Metrograph, introducing screenings of Five Element Ninjas and House of Traps.

DB here:

We’re about to leave NYC after three months. I’ll miss all the movies and museums and food and friends, but I won’t miss the noise and congestion. I especially won’t miss the obliviousness of New Yorkers on the pavement–frowning into their cellphones as they nearly collide with you, steering baby assault vehicles as big as WW II half-tracks, and letting their longleashed pooches stray across streams of pedestrian traffic (there but for the grace of dog go I).

Okay, no more geezer complaints. Remarkable, the calming influence of an onion bagel with lox and cream cheese.

Our last days here have been really busy. Kristin gave a talk to the Egyptological Seminar of New York, “Beyond Thutmose: The District of Sculptors’ Workshops at Amarna” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art on Thursday. On Friday, I participated in a Film Comment podcast with critics Violet Lucca and Nick Pinkerton. We had a good time, talking about my book The Rhapsodes and other stuff. Here they are afterward in the Film Center.

Speaking of The Rhapsodes, Saturday I went to the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, where David Schwartz had mounted a four-film series tailored to the book. The first screening, Citizen Kane in a nice 35mm print, brought out a fair number of people.

Several people told me it was their first viewing of the film on the big screen, and indeed scale helps with this movie. It becomes more looming, from that screen-filling title onward, and you can see little details cunningly embedded. I noticed a couple of new items that I may write about later this summer. (Early in our stay, I already did a Welles birthday tribute here.) You always find more filigree in Kane; it looks forward to all our modern movies with in-jokes and Easter Eggs.

After Kane and a book signing (thanks, customers), I rushed off to Metrograph, a new venue with a consummate programming policy. There I met Aliza Ma, Jake Perlin, and their colleagues before catching the Chang Cheh double bill curated by none other than RZA of the Wu-Tang Clan. You see him with Aliza, in Scope of course, at the top of today’s entry.

On Sunday I caught up with Subway Cinema/ NY Asian Film Fest co-founder Goran Topalovic and critic-filmmaker Eddie Mullins (Doomsdays) at a wonderful Serbian restaurant. Much talk of Hong Kong film, of course.

On Sunday I caught up with Subway Cinema/ NY Asian Film Fest co-founder Goran Topalovic and critic-filmmaker Eddie Mullins (Doomsdays) at a wonderful Serbian restaurant. Much talk of Hong Kong film, of course.

Later that day, after seeing Hong Sangsoo’s latest, we had a late dinner with 125% cinephile Michael Barker, Co-President and Co-Founder of Sony Pictures Classics. Amidst talk of great 30s and 40s films, we learned that SPC is gearing up several new releases, notably the Cannes hit Toni Erdmann for December.

During my stay, The Rhapsodes came out and got several reviews already. It just picked up another, a wide-ranging, idea-packed discussion from one of Cinema Scope‘s best writers, Andrew Tracy.

Our last nights have been devoted to catching up with friends we’ve missed in earlier weeks. Above are Jerry Carlson and Deb Navins with Kristin in front of the Royal Tennenbaums house in their neighborhood. Below is a shot of Kristin and me with my college friend, film publicist and director’s representative Lucius Barre.

Our time here has just flown by. I finished a decent-ish draft of my 1940s book, but I haven’t done as much on other projects as I’d wished. I did, though, give talks at the Columbia Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation (thanks, Bill Luhr, Cynthia Lucia, and Krin Gabbard), Sacred Heart University (thanks, Sid Gottlieb and Sally Ross), Tufts University (thanks, Malcolm Turvey), Videology (thanks, Erik Luers and Austin Kim) and the 92nd Street Y (thanks, Alicia Harris-Fernandez). Going Upstate, as we New Yorkers call it, I gave the James Card Memorial Lecture at George Eastman Museum (thanks, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case), did some film viewing there, and visited the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. No less fun: I met Paolo Gioli at the Harvard Film Archive (thanks, Haden Guest; blogged here) and re-met Terence Davies at MoMI (thanks, David Schwartz; blogged here).

Our time here has just flown by. I finished a decent-ish draft of my 1940s book, but I haven’t done as much on other projects as I’d wished. I did, though, give talks at the Columbia Seminar on Cinema and Interdisciplinary Interpretation (thanks, Bill Luhr, Cynthia Lucia, and Krin Gabbard), Sacred Heart University (thanks, Sid Gottlieb and Sally Ross), Tufts University (thanks, Malcolm Turvey), Videology (thanks, Erik Luers and Austin Kim) and the 92nd Street Y (thanks, Alicia Harris-Fernandez). Going Upstate, as we New Yorkers call it, I gave the James Card Memorial Lecture at George Eastman Museum (thanks, Paolo Cherchi Usai and Jared Case), did some film viewing there, and visited the annual conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. No less fun: I met Paolo Gioli at the Harvard Film Archive (thanks, Haden Guest; blogged here) and re-met Terence Davies at MoMI (thanks, David Schwartz; blogged here).

And to round things off, my blog entry on Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day is now available in Chinese here. Thanks to Jiahan Xu.

When I get back to Mad City, I must buckle down and revise the 40s book and, I hope, write a blog on types of film criticism today. Also, too: at our Cinematheque, another series dedicated to The Rhapsodes. (Yeah, the PR steamroller is relentless.) I’ll give an introductory talk and introduce the movies.

Is it lunchtime yet?

In the mood for WKW

In the Mood for Love (2000).

DB here:

For quite a while, many of us have been looking forward to a book called Wong Kar-wai on Wong Kar-wai, a collection of interviews conducted by Tony Rayns. Alas, that is evidently never to be, for reasons that Tony hints at in his new BFI monograph on In the Mood for Love. Bits of those interviews make their way into the book anyhow, along with information and ideas reflecting Tony’s unique access to Hong Kong’s illustrious filmmaker. All lovers of WKW will want this energetic, accessible study.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

In fewer than a hundred pages, many of which are occupied with color illustrations, Tony has done a lot. We get background on the production, with attention to Wong’s circuitous creative process. Beginning as Summer in Beijing, the project underwent constant rethinking, reshooting, re-editing, along with modifications even after the festival premiere. Tony draws attention to the film’s parallel with Days of Being Wild, also set in 1960s Hong Kong and Wong’s first essay in revise-as-you-go production.

The thankless task of providing a detailed synopsis is carried off briskly, sustained by many explanations of culturally specific references. We learn of the daibaitong, the open-air restaurant where both Mr. Chow and Mrs. Chan stop for a night’s noodles. We’re led to notice the inside joke about wuxia novels’ outlandish plots, as well as the changing of seasons as reflected in costumes. The synopsis is also sprinkled with critical-analytical points about parallels between the characters, relationships merely hinted at, and cross-references among the kindred films.

The talk around the Jet Tone office during the production of In the Mood for Love was of Chow Mo-wan setting out to seduce Mrs. Chan as a prelude to abandoning her: an act of wilful emotional cruelty intended as a revenge for being cuckolded himself. This inference is nowhere evident in the film as released, so Wong perhaps recycled the idea into Chow’s smiling rejection of a romance with “taxi-dancer” Bai Ling (Zhang Ziyi) in 2046–although that rejection is itself a gentler replay of the playboy’s treatment of Carina Lau’s needy hooker Lulu, also known as Mimi, in Days of Being Wild.

There’s also quite a lot about the soundtrack, with close attention to the recurring melodies in the score and to the shifts between Cantonese and Shanghai in the dialogue.

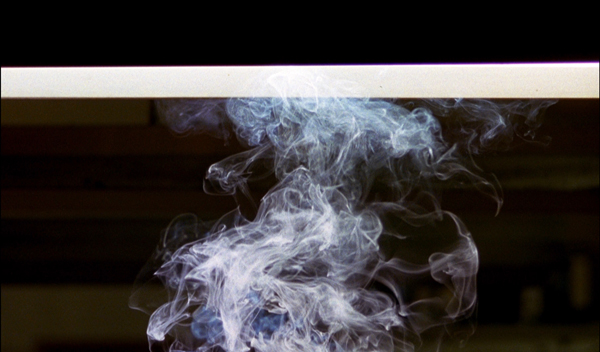

After the synopsis comes an analysis/interpretation. When the central couple reenacts their spouses’ affair, Tony suggests they’re testing the limits of their own inhibitions. He stresses the distinctiveness of Wong’s style, from its cinematic punctuation (the synopsis has emphasized the patterns of fades and straight cuts) to its handling of time–especially the strategically opaque narration, its “ostentatiously selective presentation of the action.” Of course the guilty spouses are never fully shown, but Tony also traces how time is skipped around via flashforwards and ellipses, sometimes barely noticeable ones. He points out how one cut relies on false continuity. Smoking alone in room 2046, Chow hears a knock on the door. Cut to a long shot of Mrs. Chan at the door–but she’s leaving.

We’ll never know what transpired during her visit. This exemplifies Wong’s “discontinuity in continuity”; flowing music, gentle tracking shots, and slight slow motion create a smooth surface that can conceal crucial information.

Tony has more to tell than the BFI format can squeeze in. I’d like more on the way quite disjunctive techniques fit into the film’s stylistic sheen. Wong deploys off-center framings, judicious use of depth in apparently real apartments, and variations in lighting among Hong Kong, Singapore, and Kuala Lampur. Tony’s hunch about continuity covering discontinuity might be extended to these aspects, and of course insider information on these matters would be welcome. I also wonder: Could there have been a hotel at the period boasting twenty stories? My Hong Kong friends say not. Tony argues that Wong’s films aren’t deeply political, but he was willing to violate plausibility to invoke the fateful year when HK becomes integrated into China.

Calm and ingratiating, the monograph is disarmingly personal as well. (How many books on a director start by noticing that the author has been dropped from a Christmas-card list?) It’s agreeably contrarian too. Tony teases academics, claiming at one point that the clock shots are “self-parodies” and “sucker bait” for critics who believe that Wong is the great cineaste of time. The book ends with a miscellany of observations about actors in bit parts, filmic offshoots of the project, and a little gossip. In all, reading In the Mood for Love gets you in the mood for In the Mood for Love.

Tony Rayns tells more in interviews on the Blu-ray disc of In the Mood for Love available from Criterion. That version of the film’s color seems far superior to other DVD versions I’ve seen, some of which have a dim, brownish cast. This is a hard film to replicate, though, as I found in taking 35mm frames: the tonal range is extraordinary, and your choice is often between exaggerating and lowering contrast.

Tony makes reference to the famous epilogue of Days of Being Wild that shows Tony Leung Chiu-wai, an apparently brand-new character cryptically introduced in this scene. The shot implies that there’ll be a sequel, and Wong has occasionally suggested the possibility. But there is a version of the film that includes a prologue showing the same character dressing to go out. Along with that scene is a sensuous passage in an underground gambling parlor. The sequence looks forward to imagery in In the Mood, including a sinuous shot of a woman ascending a staircase. If Wong chopped off the prologue to create the version of Days we have, he perversely left the dangling epilogue to tantalize us. For more about this “lost” version see my entry “Years of Being Obscure.”

I analyze Wong’s career, along with In the Mood for Love, in Planet Hong Kong 2.0, and I talk about The Grandmaster (which Tony considers a weak entry) here. I offer thoughts as well on Ashes of Time Redux. This project was the casus belli for Tony’s departure from Planet WKW. “The sometimes hair-raising tales of my experiences with Jet Tone will have to wait for another time.” What if we can’t wait?

In the Mood for Love.

A well-deserved honor for Criterion and Janus

Blood Simple (1984).

We were delighted to learn that our friends at sister companies The Criterion Collection and Janus Films will be receiving an award at the upcoming San Francisco International Film Festival (April 21-May 5). It’s the Mel Novikoff Award, named for an important San Francisco art-house exhibitor. (The article linked above has a full list of past winners.)

The award will be given to the heads of the two companies, Peter Becker (Criterion) and Jonathan Turell (Janus), by Joel and Ethan Coen on April 30, when a restored version of their debut feature, Blood Simple, will be shown. Before the screening, the Coens, along with Amazon Studios executive Scott Foundas, will have an onstage discussion with the two honorees. (Tickets available here.)

For more on Criterion/Janus and our links with them, see our report on Peter and Jonathan’s 2013 appearance at Il Cinema Ritrovato and our discussion of our latest edition of Film Art: An Introduction.

P.S. 8 March: Thanks to Geoff Gardner for a correction.