Archive for the 'PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book)' Category

POKER FACE: Detective off the grid

Poker Face, Ep. 10 (“The Hook”).

DB here:

Charlie Cale, an easygoing but tough young woman from New Jersey, has a unique gift. She can detect when someone is lying. She has exploited this in a career as an itinerant poker player, but after the word gets out about her ability, she winds up working as a waitress in a Las Vegas casino. A free spirit, she enjoys living from paycheck to paycheck, sharing beers and smokes with other staff. But the casino boss Stirling Ford Sr. learns of her gift and recruits her for a scheme targeting a rich patron.

That scheme collapses, and Charlie winds up having to flee across the United States. Driving the backroads, trying to stay off the grid, she keeps running into crimes in a wide range of settings. She stops at a Nevada Subway shop, a Texas barbecue joint, a stock-car race, a dinner theatre, a special-effects movie company, the venues of a touring heavy-metal band, a care facility for the elderly, and a remote mountain motel. We come to know each of these with remarkable specificity, noting details like lottery tickets and music amplifiers and Steenbeck flatbeds.

Charlie has the common touch. When she spots a lie, she’s likely to blurt out, “Bullshit!” She can freely talk and eat with working stiffs and is naturally suspicious of the plutocrats she keeps running into. She’s ready to deploy her ability to expose the less wealthy who want to exploit others. Eventually we come to learn that her sympathy for virtuous innocents may be compensation for her frosty relations with her family.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

Charlie is the protagonist of Poker Face, a ten-episode series designed by Rian Johnson. Johnson is an admirer of classic mysteries. Earlier I’ve tried to chart his debt to Golden Age whodunits, as seen in Knives Out and Glass Onion. Unsurprisingly, he planned Poker Face as an homage and an updating of the TV show Columbo.

Apart from enjoying Poker Face on its own terms, I’ve admired its efforts to innovate. In my book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder I argue that we have three useful tools for understanding plots. We can ask about the sequence of events in time; the way point of view structures our access to those events; and the way the events are broken into distinct parts. Noting how the plot handles time, viewpoint, and segmentation can help us grasp the ways Johnson has revivified the classic mystery–in ways that shape our experience.

I’ve had to indulge in spoilers, but I decided to confine those wholly to the first episode. Later episodes would justify a similar depth of analysis. And even in the first episode, I’ve tried to conceal major plot points when I could. In any event, I hope that people who haven’t yet seen the show (streaming on Peacock) might be intrigued enough to try it. It’s free although interrupted by commercials, but in a nifty use of segmentation Johnson manages to turn their timing to his advantage.

The inverted plot

Columbo, Ep. 1 (“Murder by the Book,” 1971).

The typical investigation plot begins with the crime already committed. The detective proceeds to unearth earlier events that led up to it. The alternative is, unreasonably, called the “inverted” plot. Here we witness the crime committed and perhaps are shown the motives involved. Then the detective arrives on the scene and we watch the investigator try to discover what we already know. We watch for slip-ups in what initially seems a foolproof scheme.

The inverted schema was developed most vividly in the Golden Age by F. Austin Freeman in a series of short stories. His sleuth, Dr. Thorndyke, arrives on the scene only after we have watched the culprit do the deed. The puzzle comes in trying to grasp how Thorndyke, using reasoning and scientific analysis, solves the mystery. In the process, he sometimes calls our attention to betraying details that we didn’t notice on the first pass.

This pattern of action comes off well in the short-story format, but it can be difficult to sustain in a longer tale. So the author may have the culprit resort to trying to impede or confuse the ongoing investigation, or to committing other crimes that need solution as well. These techniques come into play in Freeman’s novel Mr. Pottermack’s Oversight, which devolves into a battle of wits between Thorndyke and Pottermack.

A similar sort of stretching was common in Columbo, whose reliance on inverted plots inspired Johnson for Poker Face. The first episode broadcast, “Murder by the Book” (directed by Steven Spielberg), starts with disgruntled author Ken Franklin shooting his collaborator. Columbo, in his rumpled raincoat, doesn’t show up for the first eighteen minutes, and even after that he’s offstage during Franklin’s further schemings. These include creating a false trail for the crime and killing a witness who threatens him with blackmail.

We get some access to Columbo’s investigation behind the scenes, but the high points are his visits to Franklin. We enjoy the clash of slob versus snob when this obtuse flatfoot peppers the wealthy author with maddening questions–and always seems to accept a lie in reply. Eventually, when Franklin is trapped, Columbo reveals that he suspected him from the start; he just needed more evidence.

Despite its name, the inverted plot is usually linear. It traces events chronologically from crime to punishment, though flashbacks may provide chunks of backstory. This is where Johnson saw an opportunity to try something new. Assuming that viewers are familiar with the inverted plot schema, he juggles the sequence of events in unusual ways–exploring a different time layout in each episode.

A matter of timing

Poker Face, Ep. 1 (“Dead Man’s Hand,” 2023).

Except for the final installment, Poker Face follows the inverted schema: crime first, then investigation. But after we see the crime committed, the episode’s narration typically skips back and even “sideways” to show us circumstances leading up to the deed. Eventually the crime will be take its place in the chronological sequence–perhaps through a brief replay, or at least by reference in dialogue. Put another way, the crime segment is a kind of flashforward.

The first episode, “Dead Man’s Hand,” provides a tutorial in method. In a Las Vegas casino, the housekeeper Natalie finds horrific pornography on the open laptop of Kasimir Caine, a millionaire guest. She reports it to the boss, Sterling Frost Junior, and his fixer Cliff. They send her home. Cliff follows and shoots Natalie in her living room. He’s already shot her husband Jerry and he arranges the scene to look like a murder-suicide.

This block of brief scenes is followed by a linear story starting a few days earlier. Charlie works at the casino as a waitress, and she offers Natalie a place to stay after her drunken husband Jerry has raised a ruckus in the gaming room. In the meantime, Frost Jr. has learned of Charlie’s lie-detection talent and recruited her to watch Caine’s clandestine poker game by remote transmission. Frost will use her information about who’s bluffing in order to fleece Caine, while proving to his father that he’s a good manager.

Frost’s scheming with Charlie is interrupted by Natalie’s visit to report Caine’s pornography, so now the lead-in sequence falls into place. While Charlie is briefed further by Frost, Cliff is offstage killing Natalie and Jerry. The pivot is signaled by repeated dialogue: Cliff phones Frost (“It’s done”) and Frost resumes his explanation (“Where were we?”). The sequence of events is firmed up the next morning, when Charlie sees an online report of Natalie’s death.

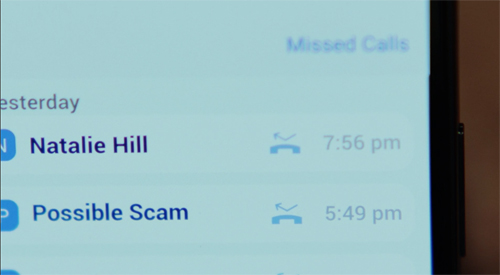

The rest follows chronologically. Charlie feels guilty for not returning Natalie’s call, made shortly before her death.

Her phone record leads her to notice disparities in the timeline and investigate, while she and Frost Jr. are preparing for the Caine scam. A slip of the tongue allows her to spot Frost’s lie about Cliff’s call, and he realizes she’s on to him. The result is Frost’s death and his father’s demand that Cliff capture Charlie. She flees and begins her backroads odyssey across America.

Later Poker Face episodes elaborate this template. Sometimes the crime is embedded in a large block of consecutive scenes, with all the backstory shown (ep. 2, “The Night Shift”). After that we skip back to still earlier events centering on Charlie’s travels leading up to the night of the murder, which takes place while she is next door in a tavern. That’s why I said that some of the scenes move sideways, showing incidents near her. This “proximity principle” is pushed further in ep. 3, “The Stall,” when Charlie is hovering just offscreen in the opening scene, as the murder conditions are laid out; the replay will reveal that.

Another variant: The leadup to the crime is extended for much longer than in the earlier episodes, with the murder coming a third of the way through the show’s running time (ep. 4, “Rest in Metal”) and the replay witnessed by Charlie over halfway through. Later episodes adopt mixed strategies. They still start with the crime, or at least the planning, and skip back in time, but they seed the later blocks with ellipses, brief flashbacks, and replays. It’s as if the series were teaching us week by week to accept an increasing flexibility in moving forward and backward and sideways, while still adhering to the basic convention of the inverted plot. We’re also helped, of course, by dialogue and intertitles telling us where we are in the timeline.

The exception to these pyrotechnics is the last episode, “The Hook.” It’s stubbornly linear in tracing Cliff’s pursuit of Charlie. It starts ab initio, with Frost Sr. ordering him to find her, and following that with scenes from earlier episodes in which Cliff misses her. In a way, this entire prologue is a kind of flashback that ends with him seizing her as she leaves a Colorado hospital. The final episode is the most conventionally readable because it isn’t an inverted plot. The crime is missing from the opening but is saved, as is common, for a climactic revelation.

What makes all this variation possible is a coordination of segmentation, viewpoint, and causal-chronological order. The blocks of time are dictated by attachment to the killer (s) or to Charlie. Typically the lead-up to the crime keeps us with the culprits. The flashbacks following the first statement of the crime are motivated because they’re attached to Charlie, who is just getting involved with the situation. The later segments are either purely tied to her, or (as in the Columbo episode) devoted to the culprit’s efforts to thwart her inquiry. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” for instance, scenes of her investigation are garnished with moments in which Frost Jr. and Cliff plan ways to circumvent her. In all, these maneuvers create pretty clever plots, their segments accented by the way that the end of a block tends to initiate a commercial break . . . just as in old network TV.

Charlie’s little gray cells

Poker Face, Ep. 8 (“The Orpheus Syndrome, 2022).

How good a detective is Charlie? Given her gift, shouldn’t sleuthing be utterly easy? Johnson has engineered his series to give her several handicaps that require her to sweat as much as any hardboiled dick.

For one thing, as a working-class woman of fairly slight stature, she starts by facing a bias in favor of the bulky, wealthy men (mostly) whom she challenges. In addition, after the first episode, she’s on the run and has to be discreet. Going to the police about anything would inevitably reveal her whereabouts to Frost Sr. Moreover, during her flight she’s deprived of what helped her crack the first case: her cellphone access to the internet. After Frost Sr. threatens that he will find her, she destroys her phone so she can’t be tracked. But now she’s got to rely on other sources of information.

Even her gift proves problematic. Unless a suspect explicitly denies committing the crim, her bullshit detector can’t know the person is guilty. Not incidentally, this condition puts a fruitful constraint on the screenwriters. They have to make sure the culprit’s dialogue circumvents the sort of declaration that Charlie would see through.

Confronted by all these obstacles, Charlie is obliged to act like a classic detective. Let’s count the ways.

For all the pledges to strict reasoning, the traditional sleuth is often triggered by intuition, the sense that something is just not right here. (The prototype is Chesterton’s Father Brown, but even logicians like Ellery Queen and Hercule Poirot are sensitive to “atmosphere.”) Charlie’s gift is an extravagant form of intuition, since it’s both illogical and impossible to explain scientifically, so even when it doesn’t expose the killer it can set off a minor alarm. In the season’s first episode, her suspicion is aroused when Frost Jr. lies about his phone conversation with Cliff.

The classic detective spots or unearths clues, traces of the criminal’s action and pointers to identity. Charlie’s case against Frost Jr. and Cliff in “Dead Man’s Hand” is built out of such traditional clues as a problematic timetable, uncharacteristic behavior (Natalie didn’t sign out when she left work), and hand dominance (would a leftie wield a pistol with his right?). Later episodes of Poker Face are packed with physical clues, from wood splinters to discarded candy wrappers. As Jacques Barzun puts it, in the classic detective story “bits of matter matter.”

Charlie is especially good at spotting the absent clue, the dog that didn’t bark in the night-time. In the first episode, she notices that video footage of Jerry hustled out of the casino shows him passing through Security unscathed.

But if he had his pistol with him, that would have been detected–which implies that Cliff kept it. Yet Golden Age conventions demand fair play: we must have access to all the clues the detective has. In his films Johnson has adhered to this, and he has in Poker Face. So we are shown the Security station in the casino twice earlier. Early on, Cliff breezes through, counting on the staff’s recognizing him and letting him pass.

Later, Charlie is stopped because her phone sets off the scanner.

Consequently, when Jerry doesn’t set off the alarm as Charlie had, he can’t be packing the gun.

Reasoning puts the clues together, but sheer reasoning isn’t enough to justify arresting somebody. There must be evidence. Charlie often finds herself convinced of the killer’s guilt but lacking something that would stand up in court. And without a cellphone she can’t resort to tricking the killer into confessing on a hot mic. Yet some solid evidence is needed to clinch the case. The screenwriters have been ingenious in finding other damning records. Episodes recruit heart-monitor charts, 16mm film, CCTV footage, and digital audio and video captured by Charlie’s helpers or the culprits themselves.

In a classic whodunit, as we approach the climax, the detective is often blessed with a stroke of good luck that advances the solution of the puzzle. It’s often something apparently trivial–an overheard conversation or a slip of the tongue, or an irrelevant detail that inspires the detective to reinterpret a clue. In “Dead Man’s Hand,” Charlie spots the TV report of Jerry passing through Security not by diligent research but by sheer accident. She’s just dropped by the bar when the broadcast appears.

One more convention, one that the series adopts gradually: an alliance between detective and law enforcement. The classic detective cooperates to some extent with the police, either wholeheartedly (Queen, Poirot, Lord Peter Wimsey) or grudgingly (Nero Wolfe). Even tough guys like Sam Spade, Nick Charles, and Philip Marlowe may exchange information with their friends on the force. At the start of Poker Face Charlie is a loner, but as the series proceeds, she gain an ally in the FBI, and because she helps him crack cases he comes to her aid on occasion. “At this rate, if I stick with you I’ll be head of the Bureau in a year.”

In all, Poker Face has engagingly modernized the inverted plot schema while benefiting from classic principles. Those permit the detective to show off powerful intuition, systematic reasoning, and Machiavellian cleverness in trapping the prey. In addition, the series has added to the gallery of admirable sleuths a hard-boiled but compassionate wise-guy woman. And it’s done with a strong dose of social criticism. This have-not from Jersey wreaks vengeance on those who victimize innocents.

Poker Face is scheduled for a second season, with Charlie once more on the run across America. We may expect that it will continue to show how ingenious play with time, viewpoint, and segmentation can revivify conventions of the whodunit. Keen fans learned to ask not only How will Charlie discover the crime we’ve seen committed? but also ask, with a teasing meta-curiosity: What ellipses and time jumps and hidden clues will we get this episode? Johnson seems unlikely to give up the game any time soon.

In Deadline, Antonia Blyth provides a very informative interview with Rian Johnson and Natasha Lyonne about Poker Face.

Martin Edwards discusses the inverted plot schema as part of a broader trend toward empirical, scientific investigation techniques in The Life of Crime (2022), Chapter 10. For a thorough survey of Freeman’s work, see Mike Grost’s discussion. Jacques Barzun emphasizes the role of physical clues in his superb essay, “Detection and Literature,” The Energies of Art: Studies of Authors Classic and Modern (1956), 313.

I discuss the inverted plot in more detail in Chapter 5 of Perplexing Plots, considering it as a hybrid of the pure investigation plot and the psychological thriller.

Poker Face, Ep. 3 (“The Stall,” 2023).

Catching up

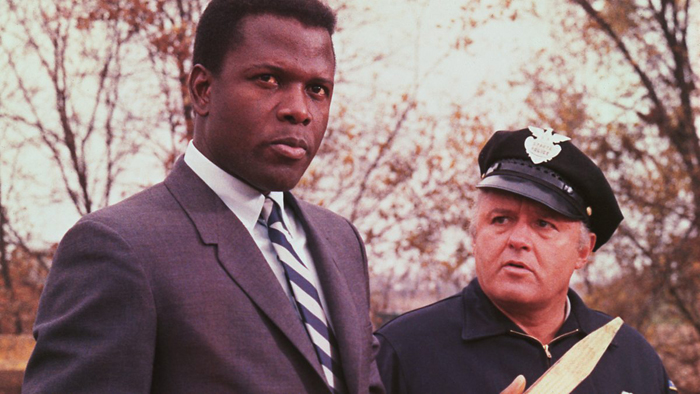

In the Heat of the Night (1967; production still).

DB here:

Some health setbacks have delayed my plans for a new blog entry, but as I clamber back from a bout of pneumonia, I thought I’d signal a couple of things I’ve read and enjoyed recently.

Walter Mirisch’s I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History is a discreet but still informative account of the career of a major producer (In the Heat of the Night, Some Like It Hot, West Side Story, The Magnificent Seven, and many other classics). Apart from offering some vivid vignettes of working with stars, Mirisch (UW grad) is very good on the corporate maneuvering that created, then sideswiped, United Artists. He swam with sharks and survived. Bonus: introduction by Elmore Leonard.

Stylish Academic Writing by Helen Sword is a lively guide to perking up your prose. Unlike most tips-from-the-top manuals, this is based on systematic research that yields some surprises. (Yes, scientific reports are allowed to use personal pronouns. No, literary theory isn’t the most opaque writing on earth: Educational research is.) There’s a lot of good advice here. I wish I’d read it before revising Perplexing Plots.

A shrewd, funny analysis of (a) the current prevalence of mystery stories and (b) streamers’ shotgun programming policies is offered by J. D. Conner in “Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. This wide-ranging essay ponders franchises, viewer tastes, and other current concerns. Extra points for noticing the Columbo revival.

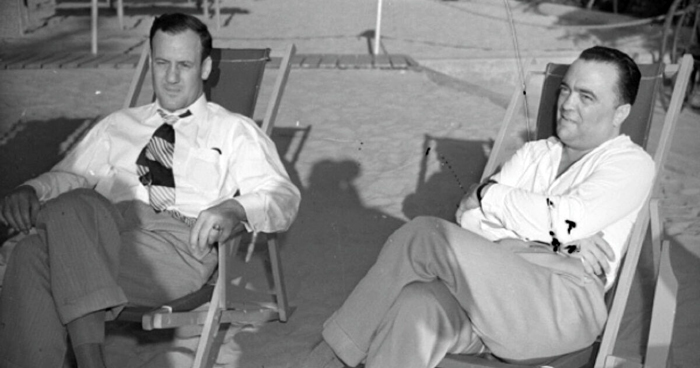

Way back in 1964, crime reporter Fred Cook caused a stir with The FBI Nobody Knows. After decades of celebrating the agency and its boss (a “confirmed bachelor” not yet revealed as in the closet), Cook’s chronicle of a frighteningly powerful force in the government inspired Rex Stout to write his top-selling Nero Wolfe book, The Doorbell Rang. Cook’s review of FBI history doesn’t out Hoover, and it does praise his ability to disclose WWII spy rings. But it concentrates on how his obsession with persecuting leftists had a long, ugly history. Today, when right-wingers are accusing the agency (staffed mostly with Republicans), it’s salutary to be reminded that the feds were long committed to ruining the lives of “communists” like Martin Luther King and ignoring the real danger of organized crime. Cook is helped by a whistleblower who reports mind-bending tales of peer pressure among agents. A lot of US history is crammed into this exciting, well-documented book.

I hope, when I can type (and think) more fluently, to post a new entry. On, I think, the power of crosscutting. Or maybe Puss in Boots: The Last Wish….

Clyde Tolson and J. Edgar Hoover in 1937. Source: The New Yorker.

P.S. 14 February 2023: In a stroke of serendipity, I learn that Paul Kerr’s new book, a historical-critical study of the Mirisch Company, is coming out next month. Knowing Paul, an expert on American independent production, I’m sure it will be deeply researched and an absorbing read. Congratulations, Paul!

P.S. 25 February 2023: Sad news: Walter Mirisch died yesterday. He was 101. The Variety report is here.

The reader is warned

Where the Crawdads Sing (2022; production still).

DB here:

When I wasn’t paying attention, along came Where the Crawdads Sing (2018 novel, 2022 film). The book was a huge bestseller, while the movie version was panned by critics but attracted a good-sized audience. It exemplifies how strategies of nonlinear storytelling have become deeply woven into mainstream entertainment.

It has an investigation plot, structured around the trial of “swamp girl” Kya, who’s accused of the murder of her boyfriend Chase in the marshlands of North Carolina. Through flashbacks we learn of her desperate childhood, as she is abandoned by her family and castigated by the townfolk. She learns to live alone in the family cabin and fills her days drawing precise images of the natural life around her. A well-meaning young man teaches her to read but he too he leaves her to struggle alone. Soon she meets Chase, a charming good-for-nothing. Is his fall from a swamp tower an accident, or did someone push him? A kindly local attorney takes her case, and the plot climaxes first in the jury’s verdict and then a twist that reveals what happened at the scene of the crime.

We’re so used to plots like this that we may forget how nonlinear they are. In the Crawdads film, the court investigation probes the circumstances of Chase’s death, but the flashbacks, instead of illustrating stages of the crime, supply Kya’s life story in chronological order. They contextualize the long-range causes of her dilemma. Accordingly, they’re narrated by her in voice-over. Titles supply the relevant timeline, dating episodes from 1963 through to 1970, the year of the trial.

All of these strategies have become familiar from a century of popular storytelling. A court case as an occasion to visit the past goes back at least to Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), although the play dramatizes testimony in a way that Crawdads doesn’t. (Its flashbacks, more boldly, are in reverse order.) The crosscutting of past and present has become common to explain (or obfuscate) ongoing story events. Tying us to a character’s viewpoint and letting the character’s voice narrate what we see is likewise a standard device in modern media. And of course an investigation plot is inherently nonlinear. The task is for someone to uncover the “hidden story” of what occurred in the past.

Simple though it is, Where the Crawdads Sing shows just how pervasive devices associated with mystery and detective fiction have become in mainstream storytelling. Told chronologically, the story would be a biography of Kya (and would presumably have to reveal how Chase died). Instead, the film becomes what Wikipedia calls “a coming-of-age murder mystery.”

By splitting the chronological story into two parts and interweaving them, manipulating viewpoint, and rearranging temporal order, the film tries to achieve interest and suspense. We know from the start that Chase is dead, so we watch every scene with him for clues as to what could have caused it. Tension gets amplified as time passes, when the shifts between the courtroom drama and the day of Chase’s death come faster and faster. These effects couldn’t be achieved with a linear layout.

One of the major points of Perplexing Plots is to remind us just how much of popular entertainment trades on narrative strategies forged in the big genre of mystery. Once we’re reminded, we can ask: How did those strategies get implemented? How did audiences come to understand and enjoy these highly artificial ways of telling stories?

I promise not to keep plugging the book on this blog, but allow me one more notice. A Q and A with me has been published on the Columbia University Press site. It tries to inform any souls whom fate has cast my way about the argument of the book. You may find it of interest.

I’m taking the occasion to note some features of the book not advertised elsewhere. Perhaps they too would appeal to you, especially if you’re interested in some of the choices a writer has to make.

Obscure is as obscure does

First, the book draws on some unorthodox sources. Most obviously, I tried to canvass obscure novels and plays that are now forgotten but that did try some experiments with nonlinear storytelling. Who’d expect a reverse-chronology play in 1921, years before Pinter’s Betrayal (1978)? A 1919 play anticipates Rear Window by offering testimony from a deaf witness and then a blind one. The first version plays out on stage in pantomime, the second in a completely dark setting. A 1936 novel offers a string of conflicting character viewpoints on a single situation, revising and correcting previous accounts, well in advance of Herman Diaz’s recent novel Trust. A 1919 play depicts a woman in different aspects, as seen by the people who know her. These instances of what we now call “complex narrative” belong to what literary scholars have called “the great unread,” the thousands of pieces of fiction and drama that haven’t become canonical through enduring popularity or academic favor.

Other precedents are dimly recalled but seldom revisited, such as George M. Cohan’s play Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913) and W. R. Burnett’s Goodbye to the Past (1934). How many people would be aware of Kaufman and Hart’s reverse-chronology play Merrily We Roll Along (1934) if Stephen Sondheim hadn’t turned it into a musical? The very existence of these marginal works helps support the premise that a lot of what we consider innovative today has broad historical roots. They just aren’t as vivid to our memory as more recent instances. But fifty years from now, will many viewers remember contemporary experiments like Go (1999) and Shimmer Lake (2017)?

The book uses other unorthodox sources. I put craft technique at the center, and so it makes sense to look at the principles that writers of fiction and drama were using. Of necessity I review the emerging idea of the “art novel” at the end of the nineteenth century, with Henry James as spokesman for this trend. In addition, unlike most mainstream literary histories, Perplexing Plots consults contemporary manuals for aspiring writers. These books are the progenitors of all those how-to-get-published books that fill Amazon today, and they reveal a surprising sophistication. Manuals allow me to show how a new self-consciousness about linearity, particularly point of view, became central to popular writing as a craft. For example, a now-forgotten critic, Clayton Hamilton, epitomizes the willingness of ambitious writers to try out new possibilities.

So one choice I made was to search out fiction, drama, and films that have fallen into obscurity. Another was to look at the nuts and bolts of plotting, as practitioners seemed to be conceiving it. These help explain why many novels and plays, major and minor, began tinkering with innovative storytelling.

Time as space

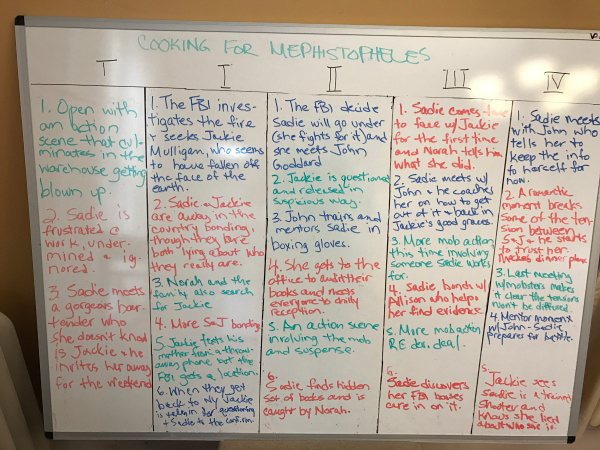

From Karen Loves TV: “Contemplations on the Whiteboard.”

A nonlinear plot has a geometrical feel to it, so one way of thinking about it is to envision it as a table or spreadsheet. Where the Crawdads Sing could be laid out in a double-column table, with each present-time scene aligned with the past sequence that follows it.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

Novelists have long made use of such charts. The most famous is that prepared by James Joyce for Ulysses, where each chapter is assigned a different color, body organ, and so on. This was published in Stuart Gilbert’s 1930 book. Because the rights to reproduction are obscure, we regrettably didn’t include it my book. No surprise, though, it’s available online.

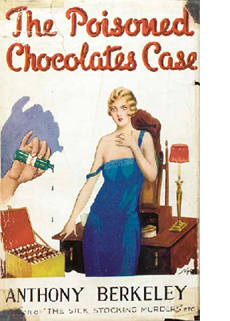

I did, however, obtain rights to a less-known but rather brilliant table included in Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Later chapters of Perplexing Plots use tables of my own devising to clarify the complicated layout of Richard Stark’s Parker novels, the chapter structures of Tarantino films, and the alternating viewpoints and time schemes of Gone Girl. There will always be readers who complain that these tables are just academic filigree, but I believe that they help us appreciate the intricate interplay of time, segmentation, and viewpoint. They show how precise the narrative architecture of mystery fiction can be.

To spoil or not to spoil

For decades, criticism of mystery fiction has labored under the expectation that a critic must not reveal a story’s ending, or the story’s central deception. In journalistic reviews of literature and film, the writer is expected to keep such things secret, but even academic studies of crime fiction put pressure on the critic to maintain the surprise of whodunit and howdunit.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

Part of the justification for hiding the legerdemain is the doctrine of “fair play.” I trace how this idea emerged in the Golden Age of detective fiction, when a story was treated as a game of wits between author and reader. In principle, nothing necessary to the solution of the puzzle should be withheld, though it can be disguised or hinted at. One thing I learned in writing the book is that fair play has become a premise of most duplicitous narratives in any genre, from horror to science fiction. People don’t realize how much the maneuvers of Psycho and Arrival owe to the belief that the audience should in principle be able to go back and see how we were misled. (We can do this with the “missing clue” in Crawdads as well.)

Fair play encourages the author to be ingenious and entices the audience to appreciate artifice-driven construction. Both effects are legacies of classic detective fiction, and they still shape much mainstream entertainment.

Thanks to Maritza Herrera-Diaz of Columbia University Press for arranging for the Q & A published on the Press site.

The phrase “the great unread” is used by Margaret Cohen in The Sentimental Education of the Novel (Princeton, 1999) and cited in Franco Moretti, “The Slaughterhouse of Literature,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61, 1 (March 2000), 208.

As I’ve indicated in an earlier entry, Martin Edwards’ The Life of Crime is a vast and entertaining survey of the history of mystery fiction. It was crucial help to me in writing Perplexing Plots. Martin, an advance reader of the manuscript, has been kind enough to discuss my book on his blog.

Other early responses to the book have been encouraging. Michael Casey reviewed it for The Boulder Weekly, and Doug Holm discussed it on KBOO on his show Film at 11. My thanks to both these commenters.

Psycho (1960): Misdirection and fair play all in one shot.

GLASS ONION: Multiplying mysteries

Glass Onion (2022).

DB here:

Rian Johnson’s enthusiasm for classic mysteries made it inevitable that I’d get interested in writing about Knives Out. Although I merely allude to the film in Perplexing Plots, I devoted a blog entry to it. While thinking about a follow-up on Glass Onion, I began a rewarding correspondence with Jason Mittell, adroit blogger and author of Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. Today’s entry reflects my thoughts after this exchange of ideas.

Despite the near-universal acclaim received by Glass Onion, it didn’t whet my interest as much as its predecessor. It’s a little too campy and overproduced for my taste. But Johnson’s ingenuity in manipulating conventions of the Golden Age detective stories by Christie, Sayers et al. makes it ripe for the sort of analysis I try out in the book. So here we go.

Needless to say, there are spoilers for Glass Onion and Knives Out. But I bet you’ve seen both films.

Tools of the trade

Knives Out.

Plotting a story is a craft, and it has some essential tools. There is, for instance, the ordering of events. Will you present events in linear story sequence, or will you arrange them in a nonchronological pattern? You can’t avoid choosing one or the other or some combination of the two.

There’s also the matter of viewpoint. Will you attach the audience to what a single character experiences, or will you roam among several characters?

And there’s segmentation: How will you break your plot up into chunks? In literature, we have sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. In theatre, scenes and acts. In film, scenes and sequences (and sometimes reels or chapters). Even one-shot movies have moments of pause or shifts of viewpoint that mark off phases of the action.

These are forced choices that every storyteller must face. It’s these three–linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation–that Perplexing Plots relies on in order to analyze both mainstream storytelling and mystery fiction.

In addition, the craft requires the audience to be engaged–at least interested, at most emotionally moved. You must choose whether to get your audience to empathize with certain characters or to keep the characters remote and unknowable. Do you want to arouse anger, approval, or some other emotion? You must decide how the choices of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation can trigger these responses.

For example, your plot can usually build empathy for a character by showing incidents in which that person is treated unfairly. Those actions will be more intense if they’re rendered from the character’s viewpoint. This is what Rian Johnson does in Knives Out when he shows Marta persecuted by the vindictive Thrombey family, and then exploited by Hugh. The disparity in power (David vs Goliath) heightens our sense of indignation and makes the finale seem to be poetic justice (My house/my rules).

Some emotions depend directly on choices about chronological sequence. If your plot signals that some past events are significant but then doesn’t reveal them, you’re using linearity to create curiosity. If the plot summons up anticipations about particular future story events, you create a degree of suspense. If your plot introduces an event that momentarily seems out of keeping with the linear story, you can summon up surprise.

Each of these “cognitive emotions” (“cognitive” because they rely on knowledge and belief) is shaped by perspective and segmentation. Creating curiosity, suspense, and surprise depends on viewpoint: each character will have different states of knowledge about the course of events. In Knives Out, Hugh Drysdale is not suffering curiosity about whodunit: he knows he did it. But because we’re attached to Marta and detective Benoît Blanc, we share their state of uncertainty–and suspense about what may come.

Similarly, decisions about segmentation will often be made based on the cognitive emotions in play. You might end a book chapter or a play’s act or a film’s scene on a note of curiosity (“Then whose body is in that grave?”), suspense (the stalker draws near the prey), or surprise (“I’m your father!”).

As my examples from Knives Out suggest, the three tools I’ve picked out have special purposes in a mystery story. Perhaps one reason for the enduring popularity of mystery as a narrative device is its ingenious use of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation to build cognitive emotions, especially curiosity. But a perennial problem of the genre is to build up other emotions. So we need sympathetic detectives and victims along with unsympathetic suspects, cops, and gangsters to engage us. Some writers also vamp up the suspense factor by putting the investigator in danger, a hallmark of hardboiled stories and domestic psychological thrillers (Rinehart, Eberhart, and their modern counterparts). Perplexing Plots traces some of these creative options through the history of mystery fiction.

Hidden stories

Evil Under the Sun (1982).

The mystery plot centered on an investigation tells two partial and overlapping stories. The investigation is presented as an effort to disclose what happened in the past, an incomplete and puzzling chain of events. Writers in the 1920s started to call this “the hidden story.”

In the standard case, the detective reveals those events and makes a single continuous story out of everything. The revelation is typically saved for the climax of the present-time story line, with the detective explaining the missing events in a summing-up. Often all the suspects are gathered and the detective reviews the evidence before presenting the solution to the puzzle. In other instances, the detective may confide the results to a friend or an official.

The summing-up is often a verbal performance, with the detective recounting the hidden story. A classic example is the Christie novel Evil Under the Sun (1941), in which Hercule Poirot explains to the assembled suspects how the crime was committed. To make this scene less monotonous onscreen, filmmakers often illustrate the hidden story by brief flashbacks, as in the 1982 film adaptation of the Christie novel. Johnson employs this strategy in Knives Out, supplying quick shots of how Hugh’s scheme was enacted.

The detective’s explanation often rests on yet another hidden story line: parts of the investigation we didn’t see. Very often the detective operates backstage, pursuing clues we didn’t notice. Sherlock Holmes absents himself for a good stretch of The Hound of the Baskervilles, leaving Watson to explore the mystery of the Moors. Only later do we learn what Holmes was up to. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe likes to keep his assistant Archie, our narrator, ignorant of information that he asks other operatives to dig up for him.

As a result, in the final summing-up, the detective’s filling in of the plot may include telling us of his offstage busywork. Again, that may be rendered on film as flashbacks to make sure the audience appreciates the sleuth’s cunning. These might include flashbacks that replay parts of the inquiry, but from a new viewpoint. In the film version of Evil Under the Sun, we see Poirot’s first visit to the cliff’s edge.

But the replay during his summing up expands this by dwelling on the vertiginous effects he feels.

In Glass Onion, Johnson finds a fresh way to treat the detective’s offstage machinations, and that depends, as you’d expect, on exploiting the three basic tools.

A package of puzzles

The most obvious innovation involves segmentation. Johnson splits his plot into two almost exactly equal halves. The first, running about seventy minutes, is a more or less complete classic puzzle.

Tech magnate Miles Bron invites his old friends for a weekend party on his private island. Their affinities go back to their days hanging out together in a pub, the Glass Onion. A fifth friend, Cassandra “Andi” Brand, co-founded Alpha with Miles, but he cheated her out of her share when she refused to expand into questionable paths. Andi shows up at the island to join what Miles calls the Disruptors. There’s Claire, an ambitious politician; Lionel, a scientist working for Miles on a new energy source; Birdie, a scatty fashionista; and Duke, an aggrieved online spokesman for patriarchy. Famous detective Benoît Blanc joins the party, even though it’s unclear who invited him.

These characters are introduced in a rapid opening sequence that shuttles us from one to the other as each gets a puzzle box. Crosscutting and split-screen imagery yield an omniscient narration; we seem to know everything. Johnson points out the expositional advantages: “The box gave it an element of fun, a spine, and a way for all the characters to be on speaker phone solving the mystery of how to open it together, so you see the dynamics between them in real time.”

Then we see a so-far unnamed woman receive a box and break it open. Finally we find Blanc himself, stewing in boredom in his bathtub. In all, a shifting spotlight has introduced us to all but one of the major characters.

Once the group assembles on the pier to board the ship that will take them to Miles’s island, the narration narrows its range and concentrates mostly on Blanc’s reactions.

In what follows, Blanc observes the others, occasionally trailing them, and asks questions about their pasts. By and large, this half of the film will be attached to him, though sometimes the narration will stray briefly to others (chiefly to give each a motive for killing Miles). The first half assigns Blanc the conventional role of curious investigator.

Miles has planned a murder game in which he’s the victim, but that puzzle collapses the first evening when Blanc solves it instantly. A new crime emerges: Duke abruptly dies of poisoning. And soon someone shoots Andi. Blanc gathers the suspects and announces he nearly has a solution. “It’s time I finished this. . . . Only one person can tell us who killed Cassandra Brand.”

In the spirit of Golden Age whodunits, Johnson has poured out a cascade of mysteries, big and small. Who sent Blanc the extra box? Why did Andi, still smarting from her courtroom loss to Miles, show up at his party? When Duke died, he drank from Miles’s glass, so who was trying to kill Miles? Duke’s pistol mysteriously disappears; who took it? The same person who killed Andi?

Johnson’s narration can be both reliable and unreliable. During the drinking session a quick long shot reveals that Miles forced Duke to take the poisoned glass. This is a daring gesture toward Fair Play (that some of us noticed), but Johnson will try to cancel our impression. He will soon offer a lying replay to blot this out.

To further swerve suspicion from Miles, Johnson uses viewpoint. We see Miles reacting in shock to a POV image of the fallen glass with his name on it, as if he were just realizing he, not Duke, was the target.

Of course he’s faking, but by privileging his viewpoint in order to underscore his reaction Johnson suggests he’s innocent. Cheating? Not really, just misleading. Johnson gives with one hand, takes away with the other–as his mentor Agatha Christie does in prose (as I try to show in the book).

Fugue states

So Blanc has a lot to explain. But instead of continuing the traditional summing-up denouement, Johnson pauses and in effect replays the first half of the film by concentrating on the detective’s offstage activities.

Turns out, Blanc has been much busier and less naive than he seemed in the first part. A conventional assembly-of-the-suspects climax would have included explanations of his scheming, but Johnson daringly fleshes these out to forty minutes that annotate scenes that we’ve already witnessed. In this play with linearity, gaps are filled, and new information is provided.

The second part starts with a young woman delivering the wrecked puzzle box to Blanc. She is not Andi but her twin sister Helen. (Yes, Johnson unblushingly taps the convention of false identity, with twins no less.) Andi is dead, killed by carbon-dioxide fumes in her garage. Helen suspects not suicide but murder and gives Blanc an account of Andi’s career through flashbacks. These bursts of nonlinearity skip freely from the gang’s youthful days to Miles’s cheating of Andi.

Moved, Blanc coaxes Helen to impersonate Andi and go to the party, as if accepting Miles’s invitation. (Blanc will convince the authorities to suppress news of Andi’s death for a time.) The two of them form a team to investigate Miles’s posse and find Andi’s killer. So now two puzzles–who sent Blanc the box? why did Andi, or rather “Andi,” show up at the island?–are set to rest. Just as important, as Knives Out focused our empathy on Marta, this second half gives us Helen as a sympathetic figure, so the puzzle element is enhanced by emotion.

Blanc’s saunters around the compound are now replayed as more purposeful, while “Andi” stands revealed not simply as an intruder but a snoop. Some scenes are only sampled, while others are fleshed out through viewpoint shifts. In addition, the narration offers hypothetical flashbacks when Helen and Blanc play with the possibilities of who might have killed Andi.

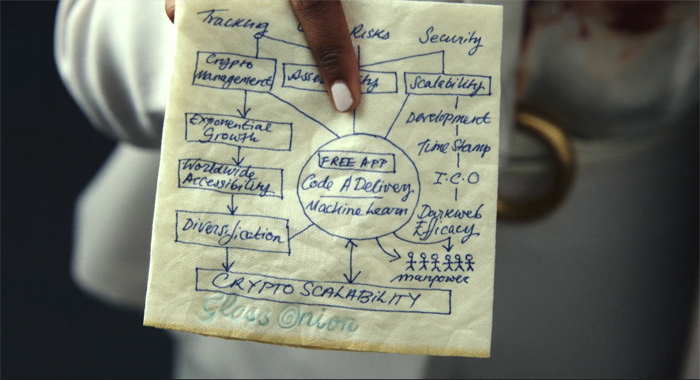

Driving the second part is the search for a crucial piece of evidence that would have won Andi the court case: the Glass Onion napkin on which she jotted down a plan for the company. After the trial she found it and told Miles’s circle; her murder was triggered by the killer’s plan to recover the napkin. When Helen finds it, she can confront Miles. In a final twist, it’s revealed that the bullet that apparently killed Helen was blocked by Andi’s diary. At her return to the group, Blanc can launch a proper summing-up and denunciation of the guilty.

The annotated replays run about 37 minutes. These incidents could have been much more concisely presented as part of Blanc’s explanation, but as Jason Mittell pointed out to me, this new plot structure gives the second part a dynamic we associate with another genre: a film tracing a big con, like The Sting. There’s a pleasure in seeing how scenes we interpreted one way now stand out as manipulated by Blanc and Helen.

Blanc’s explanations, and Miles’s efforts to block it, take another sixteen minutes. Eventually the Disruptors unite to support Andi, and Miles is facing murder charges. The film ends not with a shot of the complacent Blanc but of the righteous Helen/Andi, the co-protagonist of the second part, a figure of vengeance and vindication.

Replays that amplify and contextualize scenes we’ve already seen are common in mysteries and other genres. Johnson’s originality comes in building one long segment out of such replays. To make it work he relies on our memory of the chronological order of previous scenes to create a double-entry plot structure in which the detective’s backstage scheming revises and corrects our perception of the core action. You could lay out the action on a table of the sort I occasionally resort to in Perplexing Plots.

Johnson’s pride in folding the second half of the film back over the first part is teased when a guest at Birdie’s party explains the fugue that Miles has embedded in the puzzle box. “A fugue is a beautiful musical puzzle based on just one tune. If you layer this tune on top of itself, it starts to change and turns into a beautiful new structure.”

Johnson’s virtuoso play with segmentation has a place in the mystery story tradition; Perplexing Plots reviews several Golden Age examples. (One somewhat similar novel is Richard Hull’s Excellent Intentions of 1938.) You can imagine a version of Glass Onion that attaches its viewpoint to Blanc and Andi from the start, with the “infiltration” strategy of something like Notorious (1946) or Mission: Impossible II (2000). But that wouldn’t engage us through its gamelike, self-consciously artificiality. No film I can recall has so thoroughly routed the offstage activities of the detective onto a track parallel to that of the unfolding crime. Creating a double-column plot like this shows not only the cleverness of design demanded by mystery stories but something I stress throughout the book: the eager drive of popular storytelling toward innovation and novelty–within familiar boundaries.

Thanks to Jason Mittell for a stimulating correspondence and to Erik Gunneson and Peter Sengstock for further suggestions.

Johnson discusses how he shaped the guest assembly on the pier around Blanc’s viewpoint in “Notes on a Scene” in Vanity Fair. A lengthy piece in Vulture explains some of the citations and in-jokes in the film.

P.S. 13 January: Thanks to Antti Alanen and Fiona Pleasance for correction of two names!

Glass Onion.