Archive for the 'PLANET HONG KONG: backstories and sidestories' Category

PLANET HONG KONG: Fanned and faved

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. The next entry is concerned with directors, and the final one focuses on film festivals, with a list of a few more of my favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

For a long time film academics lived in a realm apart from film fans. But over the last decade or so, the borders have been dissolving. Following the pioneering work of Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers (1992), academics have started to study fans. More strikingly, they have joined their ranks.

Aca-what?

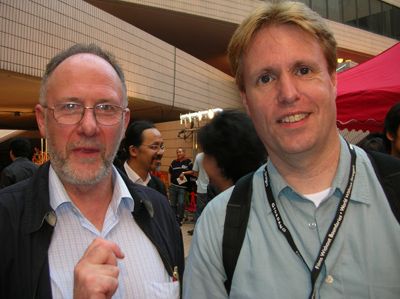

Michael Campi, fan, and Chris Berry, aca-fan. Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006.

My generation of 1970s film academics looked down what were then called film buffs, the FOOFs (Fans of Old Films), and the star-gazers who dwelled in Gollywood. We were going to make film studies serious. We over-succeeded. Actually, many of us were fans without admitting it. Many of my peers were shameless fans of Ford, Hitchcock, Fuller, et al. Is the appeal of the auteur theory a form of fannery?

Still, things seem qualitatively different now. I think that the Internet, the arrival of new generations brought up on tentpole movies and HBO, and a boredom with the Big Theory that cast its spell over official film studies, hastened the arrival of what Jenkins has called the Aca-Fan.

The Aca-Fan is a researcher immersed in fan culture without a trace of guilt or condescension. In 1973, a film professor’s office was likely to display a poster for Blow-Up and maybe another for Singin’ in the Rain (approved classic). Today the professor’s office is likely to have something more downmarket—a poster for The Matrix or Fight Club or a Beat Takeshi movie. Look on a bookshelf and you might also find a few Simpsons or Buffy action figures. The emergence of aca-fans lends support to the idea that today geek culture is simply the culture. As Xan Brooks put it in 2003, “We are all nerds now.” Or as Patton Oswalt remarks in his funny Wired essay, “All America is otaku.”

Zapped by zines

Stefan Hammond and Nat Olsen. Hong Kong City Hall, 1996.

Irresistibly drawn to Hong Kong films (the story is in the preface to PHK), I soon found myself in one pulsing zone of fan culture.

If you wanted to know something about this tradition in the late 1980s and early 1990s, your options were limited. There were the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but they were hard to find overseas. Virtually no Western scholars had studied this popular cinema, and the occasional pieces in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, Positif, and Cahiers du cinema made you want more. That more was often delivered by the fans.

They were a mixed lot: followers of the splice-ridden 1970s martial-arts imports that played in hollowed-out downtown theatres; lovers of Godzilla, Ultraman, and Sonny Chiba who saw Hong Kong as another wild and crazy cinema; big-city cinephiles who sought out recent imports at the local Chinatown house; fanboys and –girls in flyover country renting videotapes from Asian food shops and crafts stores. While Internet 1.0 cranked up, they found an easier outlet: print. Designing pages with good old Xerox and cut-and-paste, they created magazines.

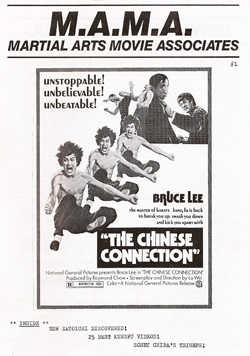

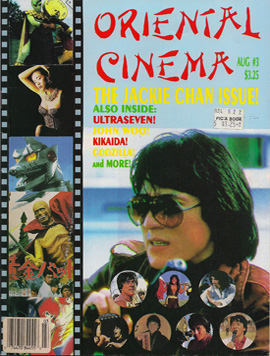

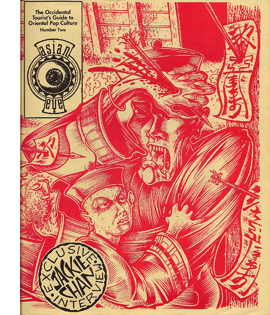

One distant progenitor was Greg Shoemaker’s Japanese Fantasy Film Journal (started in 1968), but the punkish Film Threat (1985) was also important, for it showed that deep-dyed fan publications with attitude could wriggle their way into magazine stands. Soon DIY Asian movie zines burst forth in gaudy profusion and gave the copy shops of the world a new clientele. The early production values recalled high-school poetry magazines, with ragged right margins and nearly illegible illustrations, but the content was compelling. An early entrant was the mimeographed M.A.M.A (Martial Arts Movie Associates, 1985), created by the authors of the still very useful From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas: Martial Arts Movies (1986). A step up in flair was Damon Foster’s Oriental Cinema. Lurid covers enclosed newsprint pages jammed with information, opinion, tawdry gossip, and pictures jaggedly assaulting text. Foster was probably the most colorful editor in the field, making his own films (notoriously, Age of Demons), offering his services as a mime for the blind, and boasting, “I’ve never gone to bed with an ugly woman, though I’ve woken up with quite a few.”

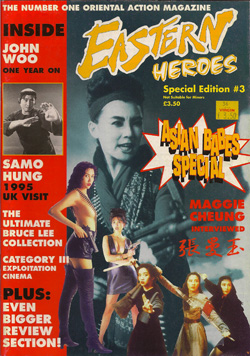

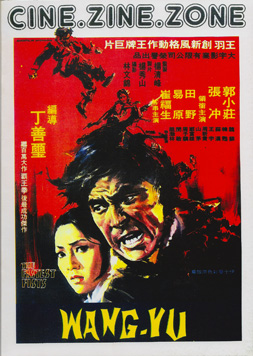

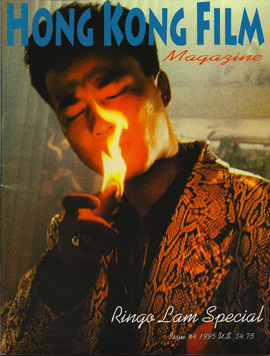

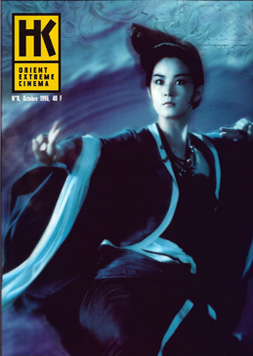

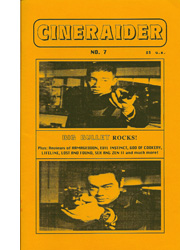

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

The fanzines were a rehearsal for the writerly gambits that would be played out high-speed on the web. Although wordage was costly in a print mag, an article could be as garrulous as a blog today. Concluding a report from a film set, the author notes: “If you found this report boring, then I am sorry. If you found it interesting, then I am glad.” The pages saw flame wars as well. “The retreading of that Amy Yip libel is but the tip of the proverbial iceberg for [your magazine] and other fanzines puking out unprovable sludge as though it were straight from CNN.” We watched all the games cinephiles play—exercising one-upsmanship, excoriating rivals, impressing newbies, and expressing pity or contempt for those wanting a snap course in hip taste. More often, there was the hospitality and a sincere urge to share l’amour fou that we find on fan URLs now. Within trembling VHS images, reduced to mere smears of color by redubbing, the writers glimpsed paradise.

I would read the zines for opinion-mongering, harsh or rhapsodic, and data delivery. Apart from pictures, usually of attractive women in swimsuits, the fanzines provided reviews (always with a ranking, usually numerical), interviews, and filmographies. There were lots of lists too; where is our Nick Hornby to commemorate the compulsive listmaking of this gang? Fandom is as canon-compulsive as any academic area, and as meticulous. One issue corrects an earlier Police Story review: “The synopsis indicated that Uncle Piao masqueraded as the aunt of Chan’s character. Actually, he disguised himself as Chan’s mother.”

Cultism reborn

Ryan Law, founder Hong Kong Movie Database and film programmer. Hong Kong, 2007.

As I discuss in PHK, upper-tier journalists usually learned of 1980s Hong Kong cinema from a parallel route, the festivals that began screening the films, usually as midnight specials. Visionaries like Marco Müller, Richard Peña, Barbara Scharres, and the New York group Asian CineVision boldly programmed Hong Kong movies. Critics, particularly David Chute in a 1988 issue of Film Comment, acted as an early warning system too. Meanwhile, the fans were amassing documentation. One zine might be given over to a film-by-film chronology of Jackie Chan’s career; another might solicit Roger Garcia to write about the tradition of Wong Fei-hong films.

One of fandom’s lasting monuments is John Charles’ vast reference book The Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997, a detailed list of 1100 films with credits, plot synopses, and the inevitable ratings. Charles, a Canadian who wrote for many zines, has been a contributor to Video Watchdog, another generous source of Hong Kong data from the 1980s to the present. Many of Charles’ reviews are available on his site Hong Kong Digital.

By the mid-’90s the modern classics had become known to cinephiles throughout the west. A 1997 editorial announced that Hong Kong Film Connection, despite having a circulation of over 5000, could not continue. Why? Clyde Gentry III explained.

The fandom base has dropped considerably because they have been hand-fed ‘the list.’ You know. The list of films like A Better Tomorrow, A Chinese Ghost Story, Police Story and others that signify the popularity of these films as a collective. It’s even more of a shame that these people will walk away leaving an entire industry with a lot more than that to offer.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Soon, the Internet created a new era in fandom, with sites like alt-asian.movies newsgroup, Brian Naas’s View from the Brooklyn Bridge, and Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database. Some zines, like Cineraider and Asian Cult Cinema (Asian Trash Cinema redux), continued for a time online. HKMDB, another monument bequeathed to us by fan passion, remains a central clearing house of information, as do LoveHongKongFilm, Hong Kong Cinemagic, and others. The Mobius Home Video Forum became a robust conversation space devoted to Asian film, and other forums sprang up, most maintaining the old zest for discovery, unexpected information, controversy, and nostalgia. At Mobius the perennial topic, So what have you been watching lately?, has amassed 32,209 posts.

The zines and the Net made fans more influential. Some turned into critics and film journalists, and a few, like Shelly Kraicer, Colin Geddes, Ryan Law, and Tim Youngs, became festival mavens too. Frederic Ambroisine became an accomplished maker of documentaries on classic and contemporary Asian cinema. With Udine’s Far East Film and New York’s Subway Cinema, enterprising fans launched their own superb festivals.

Academics respect knowledgeable people with vigorous opinions, so I found a lot to like in Hong Kong fandom. And since the phenomenon played an important part in bringing the movies to western attention, I devoted some pages in PHK to it. Wearing my historian’s hat, I wanted to trace how fans helped build up a climate of opinion that with surprising speed created a canon and gave stars and directors international fame.

There’s a personal side to it too. Otaku I was, otaku I remain. (Comics, detective stories, Jean Shepherd, Faulkner, certain TV shows, and chess as a teenager; movies came later.) As a professor, I turned late to studying fans, but once I started, it felt like coming home. “Fan” is short for fanatic, and outsiders speak of cult movies. Both terms suggest deviant, even dangerous religiosity. The analogy isn’t far-fetched. Fans pursue revelation, as often as the remote control will yield it up. This search gives their subculture its own strange sanctity. In their frenzies and ecstasies we can glimpse a quest for purity.

For a useful lineup of HK fan sites, go here. Nat Olsen maintains a gorgeous site on Hong Kong popular culture and street life from his base in the territory. Grady Hendrix is everywhere at once, but he’s often to be found at Subway Cinema, an enterprise he and Nat founded with their colleagues.

I’m inclined to think that most people who study popular culture have great fondness for the things they study. Many film academics are cinephiles (that is, lovers of the medium itself). Others confess to great admiration for films or directors they study. So there was a fan potential latent in many researchers. But some academics evidently hate the films they write about. One friend of mine, a meticulous scholar of film and culture, doesn’t seem to enjoy any movies at all. This attitude seems to be most common when the writer takes on the task of denouncing some ideological shortcomings in the movie–its covert political messages, or its portrayal of ethnic or sexual identity. How can you love a film that is criminal?

This is a complicated matter; I note in PHK that many Hong Kong films present questionable attitudes toward police procedure, women’s roles, and other topics of social importance. The problem is that by today’s standards, virtually every artwork ever made can be interpreted to be “complicit” (a favorite word), in league with some objectionable world view. Recall the critic who heard a passage in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as “the throttling murderous rage of a rapist” (though she later modified her claim). By these standards, who shall ‘scape whipping? In a perfectly just society, will we have to stop watching Minnelli movies?

Granted, there are ways for the denunciatory critic to save a film that is she or he admires. It can be found to be secretly subversive, open to a “counter-reading.” Or it can be a work that openly challenges social norms, as with Surrealist cinema, gay/Queer cinema, or the work of Straub/ Huillet. Since the 1970s we have had films, mostly avant-garde ones, that seem to anticipate every possible line of objection that an academic critic might raise. But in any case you have to acknowledge that mass-production cinema is likely to call on prejudices and stereotypes. You don’t have to go as far as Roland Barthes, who noted that a “fecund” text needs a “shadow” of the “dominant ideology.” Nonetheless, our tasks as students of film, I think, is to recognize these factors but not to let them halt our efforts to answer our questions about other aspects of the films. As for love: Well, up to a point you can love a person despite his or her failings. Why not a film?

Lisa Odham Stokes and Tony Williams are other early HK aca-fans. Both have written for fanzines and have produced insightful books on Hong Kong films. See Stokes’ City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema, with Michael Hoover, and Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. A specialist in horror and action pictures, Tony has most recently published a study of Woo’s Bullet in the Head.

On fan culture, Henry Jenkins’ most comprehensive followup to Textual Poachers is Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. An important recent collection is Jonathan Gray’s Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. Online fandom and its role in promoting a film are analyzed in Kristin’s book The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 6) and her blog here. Patton Oswalt’s newly published Zombie Spaceship Wasteland is in parts a memoir from within fandom.

Thanks to Shelly Kraicer, Yvonne Teh, Peter Rist, and Colin Geddes for help jogging my memory for this entry.

Fans all: Peter Rist, Shelly Kraicer, Erica Young, Colin Geddes, and Ann Gavaghan. Hong Kong Film Awards, 2000.

PLANET HONG KONG: Starstruck

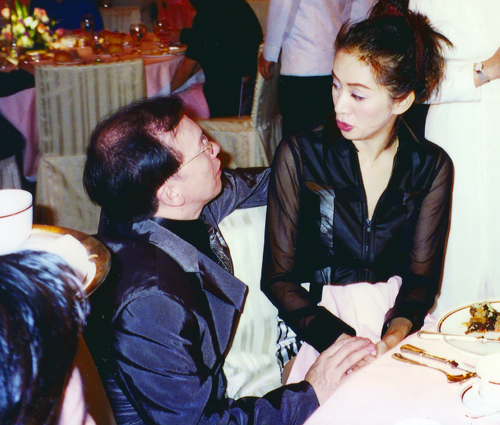

The late Anita Mui Yim-fong with Joe Junior. Hong Kong Film Awards party, April 1995.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The one following this considers western Hong Kong movie fans, the next entry focuses on directors, and the last entry reflects on film festivals, while adding a short list of some of my favorite HK movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

Today I want simply to share some photos I’ve taken of HK film performers over the last fifteen years. I’ll concentrate on the years B.B. (Before Blog)–that is, before 2007, when I began writing entries about my visits to the Hong Kong International Film Festival. Many other pictures of stars can be found in those annual entries, which can be accessed from this point on. I provide some links identifying the performers if you want to track down some films they were in. My snapshots’ quality isn’t professional–often my protagonists are bathed in tinted light–but for what it’s worth….

We reach back to the Analog Era, starting with my first visit to the Fragrant Harbour. Two couples at the 1995 Hong Kong Film Awards: Carina Lau Ka-ling and Tony Leung Chiu-wai; and Sandra Ng Kwun-yu and Simon Yam Tat-wah.

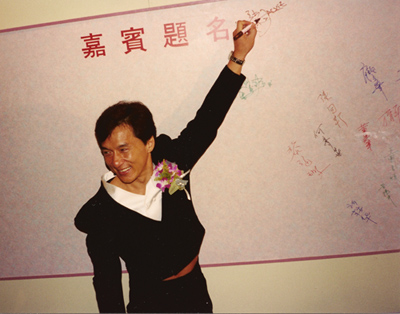

So on my first visit I was within viewing distance of two gods and two goddesses of Hong Kong film. Still, my most memorable moment came before the ceremony, when Jackie Chan came in and boldly wrote his name at the very top of the message board, above everybody else’s.

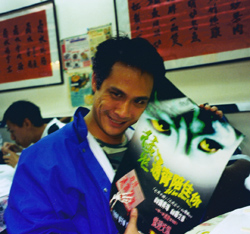

Two years later, when I was doing research for PHK, I met some performers in less public situations. This being Hong Kong, food was usually involved. Below, Francis Ng Chun-yu at a restaurant paused to promote his latest movie, Mad Stylist; and Shu Qi at Manfred Wong Man-chun’s fine restaurant.

Before you ask: Yes, I ate dinner with each of them. I was so dazzled I don’t remember a damn thing. Good thing I took pictures.

During the same 1997 visit, I managed to interview several filmmakers, one of whom was Anthony Wong Chau-sang. And what he said, I do remember. I took notes.

Alhough Anthony said it felt strange to be interviewed by a professor, he talked pretty freely. The interview ranged over acting styles (he was one of the few who experimented with the Method) and told some anecdotes about working with John Woo, Ringo Lam, and Kirk Wong. He also talked about his punkish rock music; who would think this gentle-looking guy was the lead performer on his classic “Let Thunder-God Gash All the Manic Bullies.”

One of the great things about Hong Kong is that stars from earlier eras are still treasured by younger moviegoers. I’ve seen Ti Lung, hero of many Shaw films of the 1970s and of the classic A Better Tomorrow (1986) several times, and he’s always surrounded by a swarm of young fans asking for his autograph. Here he is in a quieter moment at the 2001 Hong Kong Film Awards afterparty. Alongside is the ruggedly handsome Roy Cheung Yiu-yeung at the same event.

Earlier that evening at the Awards Michelle Yeoh was, as you’d expect, besieged by fans and news people.

Two from 2004: Jackie on the red carpet, more sedately dressed than before; and Eric Tsang Chi-wai.

Hong Kong Film Awards, 2006. An axiom of the 2000s Hong Kong cinema, Lam Suet; and Simon Yam again, this time with inveterate HK fan Mike Walsh.

Skipping ahead to 2008 and the premiere of Run Papa Run, here is the director, the ever-radiant Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, and one of her stars Louis Koo Tin-lok. I think of him as a newcomer, which he was when I was first visiting Hong Kong; but he has been in over sixty movies since 1994.

Also from 2008: Lau Ching-wan clowns in the kitchen of Paulina and Johnnie To Kei-fung, with Mrs. Lau (Amy Kwok) not at all put out. (More of Lau, from a few years earlier, here.)

One thing that struck me from my very first visit onward. Here stars are unbelievably approachable. Most enjoy meeting their fans, and they aren’t pretentious. This warmth adds to their lustre; glamorous as some stars are, they remain close to everyday people. As Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing put it, “In Hong Kong, once the audiences love you, they go on loving you for a very long time.”

The annual tribute to Leslie Cheung, held on the anniversary of his 2003 death; Mandarin Oriental Hotel, 2007.

PLANET HONG KONG: The dragon dances

The Iceman Cometh (aka Time Warriors, 1989).

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the third one. The first, a list of about 25 Hong Kong classics, is here. The second, an overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The fourth is a photo portfolio showing some stars; it’s here. Then comes an entry on western fandom, a photo gallery of director snapshots, and finally some reflections on the value of film festivals, capped by a list of some personal favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

The longest chapter of Planet Hong Kong deals with action films. Here are some further thoughts on this fascinating genre.

Four aces of action

Tiger on Beat (1988).

Directing any action sequence poses several tasks. Once the stunts are decided upon, I can think of at least four such tasks.

1. The filmmakers need to present the physical actions clearly enough for the viewer to grasp them. Who hits whom, and how? What did X do to duck Y’s bullet? Which car is pursuing, which one is fleeing?

2. If the fight or chase is to be prolonged, one needs to come up with a series of phases that take the action into different areas of a locale, or into ever more dangerous situations. The classic arc is a fistfight that pushes the combatants to the edge of a cliff or roof, with the protagonist about to be shoved over. In other words, the action scene typically has a structure of buildup.

3. An action scene can express the emotions of the fighters—perhaps wrathful vengefulness on the part of one, versus cold calculation on the part of the other.

4. Finally, the filmmaker might want to try for a physical impact on the viewer. Just as sad scenes can make us cry and comic scenes can make us laugh, action scenes can get us pumped up. We can respond physically: we can tense up, blink, recoil, twist in our seat, and so on. How can the filmmaker achieve the level of engagement that Yuen Woo-ping emphasized in an interview with me: “to make the viewer feel the blow.”

I think that 1 and 2 are basic craft skills, with 3 and 4 being measures of higher ambitions on the part of filmmakers. Not everyone agrees. Philip Noyce says that incoherence (i.e., lack of clarity) is no problem:

I don’t necessarily think the audience member is looking for coherence; they are looking for a visceral experience. If they want coherence they can watch television.

Put aside the last comment, which begs for a bit more explanation. Noyce goes on to suggest a common rationale for lack of clarity: if the action’s confusing, it’s because the character is confused too. He praises Paul Greengrass’s framing and cutting in the Bourne films because

. . . The camera was used for its visceral possibilities rather than its literal ability. We felt the chase from the inside, where sometimes disorientation becomes an asset because it’s all about the velocity. Sometimes the pursuer and pursued don’t know where they are in relation to each other.

Greengrass’s fans have employed a similar argument, not so far from Stallone’s claims about The Expendables. It seems that many contemporary directors have concentrated on the fourth task, and to some extent the third, the expressive one (but only if the fighters’ emotion is disorientation). Job 1, basic and clear presentation, has become less important.

Yet it seems to me that the contemporary blur-o-vision technique doesn’t create a very sharp or nuanced impact. In effect, filmmakers try to amp up our response through jerky cutting, bumpy camerawork, and aggressive sound (which may be a major source of any arousal the movie yields). The result often doesn’t depend on what the actors do and instead reflects what can be fudged in shooting or postproduction. But we’re wired to react quite precisely to the movements made by living beings, human or not. If the film doesn’t make those movements at least minimally clear, we’re unlikely to sense anything more than a frantic muddle.

Further, Noyce doesn’t consider the possibility that a vigorous visceral effect can be created in and through coherent presentation of the action. The choice isn’t either/ or. The Asian action tradition, especially as practiced in Hong Kong, shows that we can have the whole package, often in quite elegant form.

OTT is OK

The Hong Kong tradition is probably most evident in its resourcefulness in fulfilling Task no. 2: creating an escalating pattern of mayhem and hairbreadth escapes. Filmmakers have been quite inventive in dreaming up outlandish twists in the action. The climax of Tiger on Beat (1988), from master Lau Kar-leung, indulges in what fans would call OTT (over-the-top) stuff. Above, outside a shop selling sailboats, Chow Yun-fat uses a clothesline to snap his shotgun out and blast the gang inside—becoming a literal gunslinger. Stepping up the intensity, Conan Lee Yuen-ba gets to work in a chainsaw duet.

The striking thing is that such flagrantly loopy combat is quite exciting, even exhilarating, while the realism that Noyce and Stallone promote can leave us fairly unmoved. Lesson: Artificially shaped grace can be tremendously arousing. Don’t forget how people get carried away watching dancing, acrobatics, or basketball.

I’ve speculated that the blur-o-vision action style is popular in Hollywood partly because it can suggest violence without showing it, so the sacred PG-13 rating isn’t at risk. No such qualms afflict Lau Kar-leung, who shows the main villain pinned to a table by Lee’s chainsaw. OTT again.

Note that each shot is from a different camera setup, typical of the Hong Kong “sequence-shooting” method. In addition, the whole scene integrates many elements of the setting into the fight. You get the impression that a Hong Kong action choreographer, stepping into a barber shop or a hotel lobby, instinctively thinks: What could be a weapon? What offers cover if someone rushes in with a gun? The Tiger shop yields barrels of paint, chainsaws, and worktables that can collapse under a man’s second-story fall. Even more exhaustive (and exhausting) is the classic fight at the end of Bodyguard from Beijing (1994). Here Corey Yuen Kwai, locking his antagonists in a modern kitchen, makes punitive use of not just knives and cutting boards but also the faucet and dish towels.

So part of what engages us in Hong Kong action is the filmmakers’ inventiveness in finding new ways to develop the basic premises of fights and chases. But this Tiger on Beat sequence also gives us the action in an utterly clear and cogent way. Every shot is brightly lit and crisply composed, with vivid colors in the sets, like those slashes of red. The cutting, while fast, makes everything totally intelligible through matches on action, obedience to the 180-degree rule, and a rock-steady camera. On top of all this, the thrusts and parries are given emotional force through the antagonists’ gestures and expressions (furious, startled, agonized). So conditions 1 through 3 are satisfied.

After this scene, we might ask Philip Noyce: Visceral enough for you?

Cutting to the chase

Matters of clarity, buildup, expressiveness, and impact on the viewer raise the perennial debate among Old China Hands, Martial Arts Division. To cut or not to cut?

For some aficionados, the less cutting the better. In classic kung-fu of the 1970s the full frame and longish take let actors show that they can do real kung-fu. No need to fake it through editing tricks. Actually, though, these films are quickly cut. Directors of the period realized that if the action is cogently composed, you can edit long shots as rapidly as you can close-ups.

No doubt, there are powerful effects you can achieve in the single shot. Admirers of full-frame action can point to an escalator gunfight in God of Gamblers, in which one passage is ingeniously staged in a single deep shot. Ko Chun’ s bodyguard Lung Ng fires at his pursuer in the upper floor.

His opponent falls down the opposite escalator, but another comes up behind, glimpsed in an aperture of the railing, and he fires at Lung.

Lung rises from the extreme foreground to return fire, and in the distance we see his attacker fall out of the slot at the railing.

On the big screen, you can feel your eye leaping from foreground to background, zigzagging across the frame. The dynamism of the action is mimicked in the rapid scanning we execute in taking it in. The eye gets some exercise.

Still, editing can serve my four purposes too. Some of the disjointedness of modern action scenes, we tend to say, comes from the speed of the cutting nowadays. Yet fast cutting can be quite coherent. There are about 490 shots in the twelve-minute climax of Tiger on Beat; nearly all are from different setups, and some are only a few frames long. Since the classic Hong Kong tradition builds upon a commitment to clear rendition of the action, it can use cutting to highlight information or repeat it. At one point, Chow whips his shotgun around a doorway and yanks his rope to pull the trigger on men he can’t see. We get five shots in three seconds.

The shots run, in order, 10 frames, 8 frames, 10 frames, 16 frames, and 38 frames. (I’m a frame-counter.) The lengthiest shot is about 1.5 seconds and the shortest is 1/3rd of a second. Yet each bit of action is so pointedly presented that it’s impossible to misunderstand, while the pace of the cutting forces us to keep up.

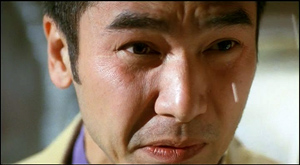

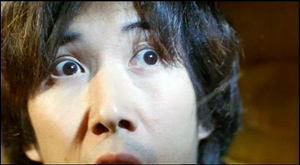

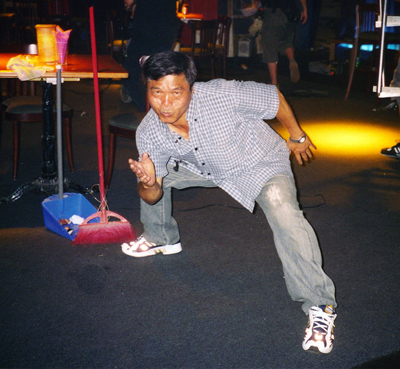

At an extreme, we have something like Sharp Guns (2001), a very low-budget, somewhat smarmy actioner that creates two spiky moments out of close-ups. Tricky On, the leader of our hit team, is pinned down alongside a mop-haired thug.

The kid recognizes him and raises his pistol in big close-up.

On, in even tighter close-up looks off, and the kid follows his glance.

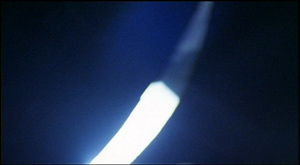

A nearly abstract blade slices into the frame and the kid turns, his face going wan from the glare of the metal.

A hand thrusts. A neck bleeds.

Rack focus to On. Cut to Rain, the female assassin. The unfortunate thug’s head in the foreground of each shot specifies where each one is.

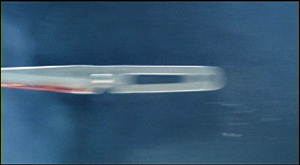

The fragmentation intensifies when soon afterward a blade whizzes leftward into the frame. In the next shot it glides past Tricky On.

On follows it with his eyes. Cut to another thuggish head, on his other side, with the blade embedded.

Rack focus again as the body slides down. Cut back to Rain, who has again saved her boss.

We haven’t had a single establishing shot in this sequence. The play of glances and turning heads, along with occasional foreground elements, lets us instantly understand that Rain has protected On from thugs on his left and right. Kuleshov would be happy.

Sharp Guns is surely no masterpiece, and you suspect that the close-up strategy pursued by director Billy Tang Hin-shing was a cheap way out. But give him credit for ingenuity, for well-timed cutting and movement, and for keeping the shots steady and legible. (Handheld shooting would dispel the force of the passage.)

Strongly marked cuts can also contribute a decorative punch. In A Better Tomorrow (1986), Chow is again pinned behind a door, and Woo cuts as he pokes his pistol around the edge.

The burst of that yellow slab in the new shot, counterbalancing the dark red of the earlier one, becomes the pictorial equivalent of a muzzle flash. Wouldn’t you like a bold cut like this in your film?

The pause that refreshes

Choreographer Yuen Bun during the filming of Throw Down (2004).

These are pretty flagrant examples. More commonly, Hong Kong cuts serve to sustain a line of motion or break one off abruptly. Later in the Better Tomorrow gunfight, Chow swivels from one adversary to another, who comes sailing in from above. (Remember: Artifice isn’t bad. And John Woo was an assistant director to Chang Cheh, one of the gurus of the 1970s martial arts cinema. In those movies people fly all the time.)

Woo is famous for using slow motion, but here what prolongs the movement are the cuts. They continue the movement of the thug as he’s hit and starts to fall, but oddly they suspend him in time a bit too.

When he finally descends, the camera pans down with him as he lands on the car. The next shot completes the movement, putting us in the car as his head smashes through the window.

Like the Tiger on Beat sequence, this passage exemplifies what Planet Hong Kong calls the pause/ burst/ pause pattern characteristic of Hong Kong action scenes. In the shots above, the soaring thug enters the first shot 7 frames before the cut. The next two shots run 13 frames and 18 frames. Most interesting is the last shot, the one from inside the car. It lasts 62 frames, making it the longest in the series. 30 of those frames show the thug’s head crashing through the window, but the remaining 32 frames have no movement except for his swaying tie. The sequence has paused for a little more than a second, sealing off this bit of action.

Another editor might have interrupted this last shot while the head was in motion, but the Hong Kong pause/ burst/ pause principle creates a distinct rhythm. A moment of stasis is followed by a stretch of sustained movement, smooth or staccato, building to a peak; then another instant of stasis. This pattern contrasts with the unorganized bustle typical of American films’ sequences.

I think that the Hong Kong tradition has shown what benefits arrive when directors strive to fulfill the first three of my four action tasks. I don’t have time here to go further, but PHK argues that the first three goals form a basis for the fourth—a strong, deeply physical engagement with the action. This need not conform to standards of realism if it galvanizes our eye and accelerates our pulse. What Eisenstein dreamed of, filmmakers in Japan and Hong Kong achieved: a fusillade of cinematic stimuli that pull us into the sheer kinetics of expressive human movement. Through precise staging and cutting and camerawork and sound, these directors offered us not an equivalent for a character’s confusion (we live in that state much of the time) but a galvanic sense of what pure physical mastery feels like.

After writing this blog, I was reading Alex Ross’s fine essay collection Listen to This and came across his essay on Verdi, which in an aside (pp. 198-199) notes the pleasures of OTT unrealism.

Most entertainment appears silly when it is viewed from a distance. Nothing in Verdi is any more implausible than the events of the average Shakespeare play, or, for that matter, of the average Hollywood action picture. The difference is that the conventions of the latter are widely accepted these days, so that if, say, Matt Damon rides a unicycle the wrong way down the Autobahn and kills a squad of Uzbek thugs with a package of Twizzlers, the audience cheers rather than guffaws. The loopier things get, the better. Opera is no different.

For more on the construction of Hong Kong action scenes, see here and here elsewhere on this site. A fuller discussion is in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

14 Amazons (1972).

PLANET HONG KONG: The little industry that could. . . . then couldn’t

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the second one. The first, a list of about 25 Hong Kong classics, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The next installments focus on western HK fandom, on director snapshots, and on film festivals, the last including a list of some personal favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

Seldom do historians get to write finis to the tales they tell. Who can tell when a process is played out? Yet sometimes you can’t avoid the sense that things have definitively ended.

That’s the case with Hong Kong cinema. Good, even great, films will still be made there, but that’s true of any territory. What made Hong Kong turn out so much lively cinema for so long was its large, robust film industry. Not exactly the Hollywood of the East, as Planet Hong Kong tries to show; it was erratic and seat-of-the-pants, less a large-scale enterprise than a cottage industry. Yet its scale did help it achieve a unique place in film history. Today there can be little doubt that the glory days of that cottage industry are gone. They started to go, in fact, about fifteen years ago.

Not 1997, 1994

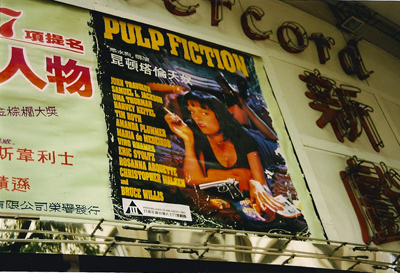

Silvercord Cinema, March 1995.

From the 1960s to the mid-1990s, the Hong Kong film industry ruled the East Asian market. Confronted with a small population in the Crown Colony (still under British control), filmmakers turned toward the much larger regional audience. They succeeded, wildly. In an era when most Asian nations couldn’t afford to import American films, the Hong Kong product boasted higher production values than films from other countries in the region (except Japan, of course). The films catered to the Chinese diaspora, a prosperous segment of most neighboring countries. Moreover, the industry offered major stars: the Shaws and Cathay stables at first, then Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Jet Li, and innumerable crossover faces from TV and pop music.

But things changed. Wasn’t the year 1997 the breaking point? After all, that was when the colony was handed over to Mainland China. Actually, PHK argued back in 2000, the slump started in 1993-1994. Thanks to overproduction, the exodus of talent, the rise of video piracy, and many other factors, the industry was in trouble well before the handover. Its problems were exacerbated by the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the 2002-2003 SARS outbreak, Internet piracy, the increasing success of South Korean cinema (and popular culture generally), and a powerful shift of investment and talent to the Mainland.

The new edition of the book gives details, but the dimensions of decline can be summarized.

*In most years between 1977 and 2002, between 100 and 234 films were released annually. (There was a significant drop in the years 1996-1998, an immediate reflection of the waning market.) After 2002, the number dropped steadily to about fifty releases per year. In 2010, Patrick Frater reports, there were 54 Hong Kong releases out of a total of 286 theatrical releases.

*Local movie attendance waned accordingly. In 1990, fifty million tickets were sold. In 1995, only 28 million were. Throughout the 1990s, ticket sales wobbled between about 17 million and 22 million. Recently, the number has been about 20 million.

*What proportion of local box-office receipts are claimed by local films? Again, 1994 proves a watershed. Before that, local films won between two-thirds and three-quarters of the market. But from 1995 on, the percentage shrank drastically. By the mid-2000s, Hong Kong productions were claiming less than a quarter of receipts. In 2009, 20.7 % of receipts went to local films—about US$31 million. The rest went to foreign imports, chiefly Hollywood movies.

*Before 1996, each year’s top ten box-office winners included between eight and ten local productions. It’s sad to trace the steep decline; by 2005 through 2008, only two films a year made it into the winner’s circle. In 2009 there was only one local film in the top ten. Last year there were two, and number ten was Gulliver’s Travels; how sad is that? America wins again.

*But Hong Kong’s market was chiefly a regional one. So how did the films do overseas? After 1994, not so well. The multiplexing of the world (one of the most important developments in global cinema history) gave Hollywood a strong entrée to places it had previously ignored. As Asian consumers became wealthier, they were drawn to the well-appointed theatres showing American movies like Jurassic Park (1993) and Speed (1994). Hollywood responded with blockbusters aimed at young and middle-class viewers in all countries, and soon its overseas receipts surpassed those from the United States. American films shoved Hong Kong films off both domestic and regional screens.

*Finally, what about China? Some locals thought that after 1997, Hong Kong would become China’s Hollywood. After all, the Mainland industry was backward, and Hong Kong had the money, the facilities, the skill sets, and the talent—especially stars that were household names in China. Sooner or later the PRC would need Hong Kong. Things did not work out that way, as I’ll discuss below.

The 2000 edition of PHK pointed to some of these factors, but an extra decade yields a longer view, and that lets us fill in more interesting detail. The old historians’ adage holds good: You really do need a stretch of time to see things more clearly. Of course you don’t have to go as far as Zhou Enlai. Asked about the effects of the French revolution, he is said to have replied: “Too soon to tell.”

Not a long time

Fire of Conscience (2010).

Speaking of Zhou, one thing I couldn’t foresee when I was writing PHK in 1997-1999 was the emergence of China as a filmmaking power. The mainland cinema was in pretty bad shape when Kristin and I visited the PRC in 1988, and things got worse in the next decade. For example, the number of cinema screens fell from about 140,000 in 1991 to 65,000 in 2001.

Again, though, things were changing. The PRC steadily stabilized the decline of its industry. It semi-privatized production, distribution, and exhibition. It let in American films and encouraged international investment to build up an infrastructure. The bureaucracy blocked a free flow of Hong Kong films into their market until 2003, at which point local exhibition was on the road to maturity. The audience grew but remained comparatively small: 115 million in 2000, 263 million in 2009. But receipts skyrocketed.

China’s cities were growing fast, and newly-prosperous urbanites turned to the new multiplexes built with Japanese, Korean, and Hong Kong investment. In 2001, box-office revenues were reported as US$77 million–about the same as tiny Denmark the same year. By the end of 2010, according to this Variety article, total box office looked to be about $1.5 billion—ahead of the 2009 receipts from the United Kingdom. (The UK is the second-biggest box-office territory in the EU.) The same Variety article quotes the head of China Film Group saying that he expected the figure to exceed $3 billion, which would easily make China the most lucrative market outside the United States.

Clearly China’s growth came at Hong Kong’s expense. A quota kept nearly most Hong Kong films out of China for nearly a decade. Now producers could enter only on the Mainland’s terms, with coproductions and joint ventures the primary options. Producers were eager to partner with what was likely the fastest-growing film market in history. After 2003 more and more Hong Kong films would have some PRC involvement—financing, location shooting, postproduction, technical staff, and of course stars. The Chinese market was so vigorous that producers began assuming they could make their films principally for the Mainland, not for their home audience. Only the most modestly budgeted film, a teen romance or slapstick comedy, could retain some local tang.

Planet Hong Kong traces this process in more detail, outlining some of the chief creative choices facing Hong Kong filmmakers in the 2000s and since. The Mainland is involved in nearly all of them, not just financially but ideologically. A historical action movie like Bodyguards and Assassins (2009) wins favor by focusing on the heroic efforts of a cross-section of Chinese to defend Sun Yat-sen during his stopover in Hong Kong. The academic, patriotic costume picture perfected by Zhang Yimou has been taken up by Peter Chan Ho-sun (The Warlords, 2007) and John Woo (Red Cliff, 2008-2009).

There is another, riskier option: Make films that can sell in the West. This has been Wong Kar-wai’s strategy as he has risen to the top of the festival and arthouse circuit. But after his venture into American indie cinema, My Blueberry Nights (2007), he too has shifted toward the Mainland, reviving the Ip Man project he announced several years ago, now known as The Grandmasters. (Ironically, so great is the power of American distribution that My Blueberry Nights was probably his best-performing film in theatrical release.) Johnnie To Kei-fung has pursued several avenues at once: while making films for Hong Kong, China, and the region he has also developed audiences in festivals and in limited theatrical/ video releases in Europe and the U. S.

There is another, riskier option: Make films that can sell in the West. This has been Wong Kar-wai’s strategy as he has risen to the top of the festival and arthouse circuit. But after his venture into American indie cinema, My Blueberry Nights (2007), he too has shifted toward the Mainland, reviving the Ip Man project he announced several years ago, now known as The Grandmasters. (Ironically, so great is the power of American distribution that My Blueberry Nights was probably his best-performing film in theatrical release.) Johnnie To Kei-fung has pursued several avenues at once: while making films for Hong Kong, China, and the region he has also developed audiences in festivals and in limited theatrical/ video releases in Europe and the U. S.

To the extent that the Hong Kong industry recovers, I’m happy to see it come back. I want it to succeed. Yet to the extent that it is obliged to serve the Mainland market and government policy, I feel a loss. Hong Kong films have become more “professional.” Scripts are getting tighter, and while this leads to strong entries like Hooked on You (2007) and Beast Stalker (2008), the old audacity seems rare. The success of slick, restrained items like Infernal Affairs (2002-2003) and Initial D (2005) may signal that most films will lack the galvanic unpredictability of the old days. CGI has made stunts more outlandish but also less convincing; Jackie Chan’s successors need no longer risk breaking a collarbone. A bravado bit of spfx technique, like the sculptured freeze-frame opening Dante Lam Chiu-yin’s Fire of Conscience (2010), has replaced the sort of open-throttle curtain-raiser that hurled you into the movie’s world.

In the prime days, the scale of production and the heedless rush to make movies to satisfy a market, to surpass your competitor, to make a killing before 1997—all that fostered a frantic, unpredictable churn. Fans found there the audacious conviction of the hell-for-leather outlaw. But entertaining as today’s movies can still be, the edge has blunted. Cellular (2004) became Connected (2008). Both are lively items, but did you ever think you’d see the day that Hong Kong turned out an authorized remake of an American movie? (Warner Bros. coproduced it.) Even English titles have become distressingly tasteful and cogent. Kung Fu vs. Acrobatic (1990), Love Amoeba Style (1997), Killing Me Hardly (1997), and Horrible High Heels (1996): those titles and dozens more teased us toward the sweet brink of nonsense. Divergence and Invisible Target and Wait Till You’re Older just don’t do the job.

Plastic boobs were involved

From Beijing with Love (Stephen Chow/ Lee Lik-chi, 1994).

Yet all signs of life haven’t been muffled. In the current restrictive climate, Johnnie To can make eccentric, occasionally shocking films like Running on Karma (2003) and Throw Down (2004). I take comfort in learning just last weekend what terminated Stephen Chow’s directorship of The Green Hornet. According to one report he proposed to plant a microchip in the hero’s brain and have Kato control him with a joystick. In an Entertainment Weekly article not online, director Michel Gondry claims that Chow’s plans were too far out. “Really, really crazy ideas that you would not dare bring to a studio. AIDS was involved. Plastic boobs were involved too.” That Gondry, one of Hollywood’s approved Wild Things, can find something Chow proposed over the top gives you hope.

A couple of months before the handover, I was in Kowloon talking with a cab driver. He told me confidently, “Chinese people are born capitalists. We know very well how to make money. We will never accept Communism.”

“But,” I said, “the Mainland has had a Communist government for forty years.”

He shrugged. “Forty years is not a long time.”

Now that is really taking the long perspective. Maybe I shouldn’t write finis. The prospects of Hong Kong cinema? Too soon to tell. Ask me in forty years.

Many of the statistics cited here and in Planet Hong Kong come from the Hong Kong Motion Picture Industry Association and from that invaluable source on world film trends, Screen Digest. We discuss the importance of multiplexing in the process of globalizing cinema in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For an example of the ideological finger-wagging practiced by China’s officialdom, go here. (Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the link.) The Michel Gondry quotation comes from Benjamin Svetkey, “Hornet’s Buzz Gets Better,” Entertainment Weekly (14 January 2011), p. 25.

PS 24 January: Soon after this entry was published, Luo Jin wrote me with some comments. I’m sorry about the delay in posting them, but I wanted to recheck my sources and dig up new ones.

I just read your latest blog entry. Some numbers are different from my knowledge, so I provide them below. I hope they are helpful.

“The number of cinema screens fell from about 140,000 in 1991 to 65,000 in 2001.”

In general the screen number in China refers to the screens in large and medium-sized cities, excluding small cities and rural areas. That is because in most small cities or counties (like Jia Zhangke’s hometown Fenyang), there is no film theater at all. And in the rural areas, only mobile screens are available. Tickets are free, so there are no B.O. receipts. In all, an accurate number of screens is hard to count. I checked the official report, and the number of cinema screens in 2002 is given as 1,581, increasing annually to 6,223 in 2010. If I am not wrong, the number in the United States is around 40,000, so it couldn’t be that much in 1991 to 2001 in China, even taking the rural mobile screens into consideration. Reportedly the rural mobile screens numbered about 40,000 in 2010.

“In 2001, box-office revenues were reported as US$77 million”

In the official report, the domestic B.O. revenue in 2001 is 890 millions RMB, equal to US$108 million by 2001 exchange rate.

My sources for Chinese exhibition statistics, as indicated above, were the annual reports in Screen Digest, which I have always found reliable in relation to other countries. I assume that the SD sources counted the rural mobile screens in the total, but otherwise I don’t know how to explain the discrepancy. Similarly, the differences in reported box office revenue may need to be checked against indigenous sources. The most recent Screen Digest annual exhibition report (November 2010) cites for 2009 34,233 screens in China (again suggesting that mobile screens are counted) and a box-office take of 6109 billion yuan, or US$906 million. The latter figure corresponds to other reports in Western sources. On screen counts, other sources suggest numbers closer to Jin’s. A 2008 Variety article mentioned that there were currently only 3000 screens in the country, while a mid-2010 Variety piece claims 5000 by 2009. If my claims prove unfounded on these points, I regret the errors.

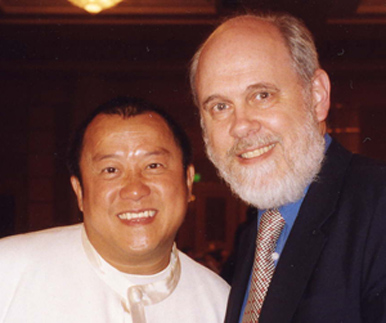

Hong Kong Film Award winners, 2000. Among them, top row, from left: Ng See-yuen (with orchid), Carrie Ng Ka-lai, Law Lan, Andy Lau Tak-wah (white suit), Ti Lung, Cecelia Cheung Pak-chi, and Arthur Wong Ngok-tai. Bottom row: Manfred Wong Man-chun (in profile), Gordon Chan Ka-seung, Teddy Robin Kwan, Eric Tsang Chi-wai, Tung Wai, Cheung Tung Cho, Lam Kee-to (in spectacles). Thanks to Athena Tsui and Luo Jin for help in identification.