Archive for the 'PLANET HONG KONG: backstories and sidestories' Category

PLANET HONG KONG now in cyberspace

DB here:

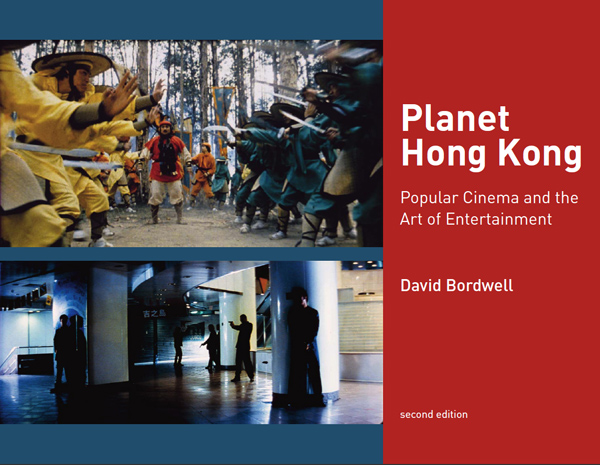

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run a daily string of entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have a chance to raise in the text. This is the first one. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. The fourth, a photo portfolio of HK stars, is here. The following ones deal with western fandom, some Hong Kong directors, and final reflections on film festivals and a list of other intriguing movies. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

± 25 classics: A cheat sheet

Rouge (1988).

I have an aversion to list-making (some day I’ll explain), but I’m often asked to recommend Hong Kong movies to people wanting a quick start. So I’m launching this suite of daily entries around Planet Hong Kong by charting some widely recognized high points in this effervescent cinema.

Some items are important for their historical influence, some for their intrinsic quality, some for both. I’m restricting myself to the years after 1960, although there are several influential and powerful films before that (e.g., In the Face of Demolition, 1953). Still, if you want a fair sample of this cinema’s output you must sample these more or less official classics. If the bug bites, you can supplement them with other items that I’ll mention in passing here and in the days to come. Several of these films are discussed in more detail in the book, and most are available on DVD.

The Wild, Wild Rose (1960): Cathay (to use its shortest name) was one of the two major companies of the 1960s and in this brassy show-business drama Grace Chang (Ge Lan) had her defining role as the Carmen of the nightclub scene. Another Grace Chang classic is Mambo Girl (1957), and you can get a sense of the gorgeous star culture of Cathay by seeing her and other top actresses in Sun, Moon, and Star (1961), sort of a Hong Kong Gone with the Wind.

The Love Eterne (1963, above): This adaptation of the “plum-blossom” opera was given lavish treatment by the Shaw Brothers studio, the major studio of the period. Li Han-hsiang’s spectacle of colorful costumes, big studio sets, and gender masquerade won several awards and helped establish Hong Kong films across Asian markets. Li went on to make many other sumptuous costume pictures, as I discuss briefly here and in subsequent entries. This web essay focuses on Shaws’ anamorphic output.

Come Drink with Me (1966): The first Shaw entry in its new martial arts cycle, pioneered by King Hu. In an inn various characters in disguise meet and bluff one another; eventually the woman warrior Golden Swallow takes on all comers. Strictly speaking, King Hu’s other films belong to Taiwanese cinema, but he is one of the greatest of all Chinese directors, so you will naturally want to see Dragon Gate Inn (1967), The Fate of Lee Khan (1973), The Valiant Ones (1975), and his official masterpiece, A Touch of Zen (1971). I give him a fair amount of space in Planet Hong Kong because of his historical importance and his innovations in the aesthetics of action. I talk a little about those innovations here.

Golden Swallow (1968): Shaws’ dominant director from the late 1960s onward, Chang Cheh specialized in films of “staunch masculinity,” martial arts pictures that replaced the female-centered romances and opera films. Golden Swallow shows the woman warrior, the nominal protagonist, muscled aside by a typical brooding Chang hero—Jimmy Wang Yu, acting as if he still nursed a grudge from being The One-Armed Swordsman (1967). Later Chang developed the masculine pairing of Ti Lung and David Chiang Da-wei (Blood Brothers, 1973) and the brawny teamwork of what came to be known in the West as the Five Venoms (as in Invincible Shaolin, 1978).

Fist of Fury (1972): Child star Bruce Lee came home from Hollywood, and his first kung-fu film, The Big Boss (1971), was a sensation. The most influential star in all Hong Kong cinema, Lee stands at the center of his classics; the plots, staging, and shooting simply set off his glowering charisma. Fist of Fury provides a string of archetypal scenes: he wipes the floor of a dojo with its students and master, he kicks to splinters a sign barring Chinese from a park, and he ends his life by hurling himself, shouting, into a hail of bullets. Remade as the no less enjoyable Fist of Legend (1994) with Jet Li.

The House of 72 Tenants (1973): The success of Shaw Brothers’ export-driven Mandarin-language product led to a decline in films made in Cantonese, the local language. (Hong Kong audiences heard Bruce Lee dubbed into Mandarin.) 72 Tenants, based on a popular play, brought back Cantonese cinema in a crowd-pleasing guise. Under the direction of veteran Chor Yuen, the crisscrossed stories of neighbors became an enduring reference point for local cinema—cited again last Lunar New Year in 72 Tenants of Prosperity.

The Private Eyes (1976): Another victory for Cantonese vernacular cinema. The Hui brothers, popular from television, brought their episodic sight-gag comedy to the big screen and were among the biggest stars of the 1970s. There are many classic scenes, including Michael and Sam’s sleight of hand with candies, a shark attack in a kitchen, and a bout of chicken aerobics—plus a weird contagion of neck braces. See also Security Unlimited (1981) and, for fairly daring mockery of Beijing, The Front Page (1990).

The 36th Chamber of Shaolin (1978). As his employer Shaw Studios was fading from the scene, Lau Kar-leung (aka Liu Chia-liang) created in nearly twenty films a virtual encyclopedia of the kung-fu tradition. Any choice among the films is arbitrary (I’ll mention more in a future entry), but let this exuberant display of color, movement, and emotion stand as an outstanding accomplishment. A young man burning with rebellion enters the Shaolin monastery. Through persistence and discipline he achieves the highest distinction and returns to his home town to fight the Manchu oppressors. Featuring the director’s brother Gordon Lau Kar-fai and Lo Lieh, both martial-arts icons.

Young Master (1980): Jackie Chan’s comic kung-fu caught fire in Snake in the Eagle’s Shadow (1978) and Drunken Master (1978). Young Master is a prime instance of his rubbery energy and bottomless masochism. It benefits from extended byplay with Yuen Biao, splendid jumper, and Shek Kin, patriarch of the Hong Kong martial arts movie. Soon Jackie would show both ambition and directorial prowess in Project A (1983), his leap into big budgets and pan-Asian superstardom.

Aces Go Places (1982): The most successful franchise in Hong Kong history was launched by this jaunty action comedy, stuffed with pratfalls and high-tech chases. The buffoonery was carried off by an unruffled Sam Hui Koon-kit and a sprightly Sylvia Chang Ai-chia, not to mention the robots. Any film is improved by robots.

Boat People (1982): Ann Hui On-wah, a practitioner of serious drama for over thirty years, established her reputation in world cinema with this poignant story about a photographer’s discovery of children cast out by war. Her earlier film about Vietnamese refugees, Story of Woo Viet (1981), gave TV actor Chow Yun-fat his first major film role. Another characteristic Hui work is Song of the Exile (1990).

Zu: Warriors of the Magic Mountain (1983) Which early film by Tsui Hark to choose? The Butterfly Murders (1979) looks forward to his recent Detective Dee; the hectic We’re Going to Eat You (1980) suggests Romero turned loose in China; many critics pick Dangerous Encounter—First Kind (1980), a rough-edged Buñuelian indictment of class differences. With Zu, however, Tsui showed his resolve to update classic genres, in this case the Cantonese swordplay fantasy, using modern technique and special effects—a trend that has continued right up to the recent Storm Warriors (2010). Go here for more thoughts on Tsui.

Police Story (1985): Possibly Jackie Chan’s directorial masterpiece. A rip-roaring auto chase through a hillside shantytown, capped by a runaway bus, would be the climax of any other movie, but here it’s just for openers. The film ends with a fight in a shopping mall that, for precision and visceral impact, deserves to be ranked with the great sequences in film history. More on this scene here.

Peking Opera Blues (1986): The woman warrior’s shining hour, complete with the obligatory cross-dressing. Tsui Hark moves toward historical action/ adventure in a breathless movie that showcases three great beauties: Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia, Sally Yeh, and Cherie Chung Cho-hung.

A Better Tomorrow (1986): The film that defined a generation and cemented Chow Yun-fat’s star stature. John Woo came out of Taiwanese exile to make a film that revived the Chang Cheh spirit of brotherhood, made even more romantically doomed by the idea that Hong Kong was living on borrowed time.

Rouge (1988): A courtesan’s ghost revisits contemporary Hong Kong and finds that no one else is willing to die for love—not even the man who pledged to join her in death. Stanley Kwan Kam-pang’s delicate yet straightforward handling of the plot, refusing all special effects, gives an extra poignancy. Others would suggest Kwan’s Centre Stage (aka Actress, 1992), a biographical study of the great film star Ruan Lingyu.

The Killer (1989): The Chow/ Woo collaboration that brought them to the attention of the West. Often imitated, at home and abroad, the original retains its bold lyricism and outlandish emotion: crime and punishment as (mostly male) melodrama, accompanied by cadenzas of annihilation. To be supplemented by A Better Tomorrow II (1987), Bullet in the Head (1990), and Hard Boiled (1992), all of which brought awed fanboys to their knees.

God of Gamblers (1989): A financial triumph for bad-boy producer/director Wong Jing and the definitive gaming movie for a town that loves a bet. Shamelessly cheesy in its plot mechanisms, surprisingly elegant in its direction, the movie yanks us from laughter to pathos. Plus Chow Yun-fat in a tuxedo. To be seen alongside Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s parody All for the Winner (1990).

Days of Being Wild (1990). Wong Kar-wai’s breakthrough film about young people adrift in the early 1960s. A dazzling array of stars (Leslie Cheung Kwok-wing, Maggie Cheung Man-yuk, Andy Lau Tak-wah, et al.) creates a languid movie about the magnetic pull of selfish passion. For many local critics, the most important film of the last thirty years. I discuss a rare alternate version of the film here.

Once Upon a Time in China (1991): Tsui Hark doing Movie Brat revisionism again, this time with the Southern Chinese folk hero Wong Fei-hong. This flamboyant exercise in fervent nationalism ushered Mainland wushu champion Jet Li onto the world stage. If Bruce Lee radiated a cocky sexual energy, this film helped establish Li’s star image as a shy and chaste warrior.

Chungking Express (1994)/ Ashes of Time (1994): A coin-flip. The first showed that Wong Kar-wai could make a movie fast, cheap, and charming. The second showed that a swordplay film could be drenched in romantic longing. Both bristled with audacious storytelling tactics. Chungking spliced two stories together (prefigured in the way characters bump into each other), while Ashes zigzagged and spiraled in time, refusing plot certainties but offering a hypnotic reverie instead. Western critics and fans, notably one Q. Tarantino, sat up and noticed. PHK devotes an entire section to Chungking; go here for more on Ashes of Time.

The Mission (1999): Johnnie To Kei-fung’s stealth classic. Made on a shoestring, shot in less than three weeks (without a developed script), filled with great character actors, this ascetic polar has some of the subtlest plot twists in Hong Kong film. If Kitano Takeshi in his prime had made a Hong Kong film, it might look like this. Of course the mall shootout has become a classic.

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000): This US-Hong Kong-Taiwan project showed that the world was ready for the wuxia pian, or film of heroic chivalry. CTHD became the top-grossing foreign-language film in U. S. history. The versatile Ang Lee centered the drama on two couples, one young and one older, and their life in the jianghu–that virtual, larger-than-life world of forests and rivers that tests warriors’ righteousness. Lee’s film prodded Zhang Yimou to make the artier Hero (2003), first in a procession of historical dramas that helped revive the Mainland film industry.

In the Mood for Love (2000): Julia Roberts’ favorite movie, I’m told. Revisiting the period and perhaps some of the characters of Days of Being Wild, Wong Kar-wai evokes muffled yearning through averted glances, hidden faces, radiant costumes, and a typically spine-tingling soundtrack. This Cannes prizewinner was given a sequel, 2046 (2004), that is harsher but no less romantic in its commitment to cherishing the past.

Infernal Affairs trilogy (2002-2003): A deliberate effort to break away from the hell-for-leather action film, the IA trio showed that Hong Kong filmmakers could construct a taut, restrained crime plot. The first installment is a compact, efficient suspense exercise, the second a wide-ranging exploration of betrayal, and the third a fairly daring experiment in time-shifting and subjectivity. Many recent crime films have taken their cues from the trilogy’s huge box-office success. Portions were remade as The Departed, and for once it was the Hollywood movie that was overblown (not least the contribution of Mr. Nicholson). I set down some thoughts on the two versions here and here.

Kung Fu Hustle (2004): Stephen Chow purists may consider it a case of comedic elephantiasis, but this big-budget extravaganza is historically significant for winning worldwide distribution and big box-office. Kung Fu Hustle is also packed with engaging CGI-enhanced gags, on every scale from tenement demolition to cobra-smooching. One of the funniest scenes will encourage you not to use the phrase “hair on fire.” The even more inventive Shaolin Soccer (2001) was Chow’s previous step toward making movies at once China-friendly and globally marketable; not for nothing is his company called The Star Overseas.

Later this week I’ll offer a list of other Hong Kong films that I think are worth attention. (So wait until you’ve seen all my picks before writing me to point out titles I’ve omitted here!) And somewhere I’ll try to wedge in some outstanding sequences. This is nothing if not a cinema of rousing set-pieces.

Nearly all the films I mention are available on DVD, with European and American editions usually being of superior quality to Hong Kong editions. Many of the filmmakers mentioned are discussed in other entries on our site; check the Directors category on the right.

In 2005, Chinese critics assembled a list of the 103 best films from the PRC, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. That list can be found here.

PS 3 Feb: Another list of top Chinese films, tilted somewhat toward Taiwan, is here.

A Better Tomorrow (1986).

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

The East Is Red (1993).

DB here:

In about two weeks, we try something new here. It’s an experiment in self-publishing, like everything on this site, but this time we offer a new version of an oldish book.

Planet Hong Kong was published in 2000. It sold pretty well for an academic book, shifting about 7000 copies through 2007. It was translated into Chinese twice, once in Hong Kong and once on the mainland. It also got encouraging reviews; I’ve put up links at the end of this entry.

At some point in 2008, Harvard University Press took the book out of print, a decision I learned about accidentally in spring of 2009. The story is here.

Since then, the book has become rather scarce; only about twenty copies are currently offered on Amazon. Rather than letting the poor thing fade away, I considered revising it for the web. The more I thought about it, the better the prospect looked. I could add as much to the text as I wanted. The text could be corrected, updated, and supplemented in the future. I could add photos, lots of them, and they could be in color. The text would be searchable. And instead of waiting nine to thirteen months to see the result, I could see it in weeks.

Moreover, readers could use the book as they liked. If it was presented as a pdf download, they could read it on a computer or on several models of e-book readers. They could also print out all or part of it. Interestingly, when I asked students and faculty if they’d use the book, nearly all said they’d print it, or let a facility like Kinko’s do it. All in all, it looked like an experiment worth trying.

[Insert montage of fluttering calendar pages here]

God of Gamblers (1989).

Since July I’ve spent virtually all my time on the book, with a break to go to the unmissable Vancouver film fest. Reworking the manuscript, watching and rewatching films, and preparing new material kept me from writing other things I had planned. No blog for Godard’s eightieth birthday, aiming to defend Film Socialisme as an intelligible part of his career. No web entry on the remarkable films of Kon Satoshi, creator of Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, and The Girl Who Leaped through Time. No discussion of the 1950s-1960s art-cinema canon in the light of Tino Balio’s fine new book on that period in U. S. film culture. No speculations on the psychological processes aroused by a movie’s opening scenes. Maybe next year.

Instead, apart from two quick entries provoked by Inception, I was absorbed in Hong Kong movies on film and DVD, notes from ten years of film festivals and conferences, and plenty of books and websites. Two blog entries, one on coincidence and the other on Jackie Chan’s Police Story, were chips from the workbench. As for my seeing recent releases, The Social Network and Megamind have been about it.

Now, after a month of fourteen-hour days, Planet Hong Kong redux is close to ready. I hope to make it available on this site during the week of 20 December.

The beast has grown in captivity. The first edition ran about 130,000 words; the new version adds 40,000 words. (In defense, I remind you of Adorno explaining why The Authoritarian Personality turned out so long: “We didn’t have enough time to make it short.”) There are over 150 new stills, all in color and many from 35mm prints. But no clips! These films are too beautiful to be reduced to those wretched mutants you get on YouTube. Besides, I don’t have the rights.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0 will not be free. My Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema and Kristin’s Exporting Entertainment are free online, but neither of those was revised, and we absorbed comparatively little of the costs of production. By contrast, the digital PHK is the fruit of a lot of paid labor. Heather Heckman and Mark Minett did excellent scanning and Photoshop tweaking, and Meg Hamel, our web tsarina, designed the book and is making it web-ready. I’m still reckoning the cost of the e-book, but it will be $20 or less. Payment will be rendered unto Caesar, aka Caesar Bordwell, via PayPal.

Here’s a sample page from our beta version. I’m still fiddling with the text, but the design looks to me like a nice compromise between the stability of a book page and the flow of a website. The file I’m using here is low-resolution, and this frame from it is a paltry 72 dpi jpeg, but the final pdf page should look very sharp. For curious boffins, the 35mm frame stills were scanned at 2000 dpi and reduced to 300 dpi for insertion. We don’t know yet how big the whole book’s file will be, but of course Meg will optimize it for downloading.

By the way: No, Wong Kar-wai did not invent the luscious image of the yearning woman.

Once the book is up, I plan to add a Hong Kong picture gallery to this site. It will include snapshots of celebs and fans from across the years 1995-2010.

ISNAQs (Infrequently, Sometimes Never, Asked Questions)

Enter the Dragon (1973).

PHK isn’t a comprehensive history of Hong Kong filmmaking; for that you must turn to Stephen Teo’s Hong Kong Cinema: The Extra Dimensions. Nor is it a fan’s guide to the wild and crazy side of this local cinema. Stefan Hammond’s two books handle that task nicely, and there are many similar handbooks since. Most strikingly, the fanboys have been usurped by the professors. A geyser of academic books and articles about Hong Kong cinema burst in the new millennium, along with invaluable documentation from the Hong Kong Film Archive and the Hong Kong International Film Festival. My book doesn’t rival these.

What does this book do, then?

I try to design my books in layers, with different implications and possibly different readerships, at each level. The first and founding layer of Planet Hong Kong is my effort to convey the sheer pleasure offered by this filmmaking tradition. I write as an enthusiast for other enthusiasts, and for potential converts. In this respect, PHK is an academic dressup of a noble gonzo tradition. Hong Kong cinema has benefited from the gusto of admirers like Ross Chen, Lisa Morton, Stephen Cremin, Grady Hendrix, Stefan Hammond, Chuck Stephens, Richard Corliss, David Chute, Howard Hampton, and other lively writers. This cinema inspires dazzling, sometimes headbanging appreciations from critics.

Next there’s a historical layer. Hong Kong cinema is, I’m convinced, an important “national school” in world film history. It shaped global popular culture to a degree matched only by the westerns and gangster films turned out by the Hollywood studios. Every video game that includes martial arts, every American action movie, and every comic book showing a sword-wielding superhero owe a lot to Bruce Lee and the cinema he springs from. Less obviously, Hong Kong innovated approaches to film form and style that remain striking today. When I wrote the book, this artistic heritage was almost completely unappreciated, by both general audiences and specialized film scholars. The situation is a little better now, but the case always needs restating. Through close analyses of many films and sequences, the book tries to show the originality and force of the Hong Kong touch.

Another layer up, the book asks how popular cinema works. The clichéd split between “art” and “business” isn’t much help in understanding mass-entertainment film. The business relies on artistic traditions, and those traditions in turn are born from and shaped by industrial factors–not just constraints but also enabling opportunities. Hong Kong film provides a case study in how a mass-entertainment movie builds its effects on genre, star appeal, storytelling strategies, and stylistic tactics. It shows vividly how a media industry relies on conventions, and how artists tap those, stretch them, and sometimes twist them out of recognition. My interviews with several writers, directors, choreographers, and actors helped me understand the ways that creativity could be fostered by craft traditions.

At the most general level, PHK is a small-scale demo of an approach to asking questions about cinema. It shows how we might systematically study the principles of construction informing popular filmmmaking. Stealth poetics, in other words.

The old and the new

Leave Me Alone (2004).

The big changes in Asian cinema of the last decade make the original book something of a historical artifact itself. I did the research across the 1990s and wrote nearly all of it in 1998. Its emphases reflect issues circulating in fan and academic culture at that time. DVDs, introduced in 1997, had not become widespread, and VCDs were unwatchable. (Still are.) Most of the films that mattered had to be studied on film copies, although laserdiscs offered a passable backup in some cases. VHS tapes were seldom letterboxed, but laserdiscs often were.

The biggest constraint on the book was the scant availability of Shaw Brothers films on any format. Thanks to the Hong Kong International Film Festival, trips to archives, and the film collector’s market, I was able to see quite a few, but nothing like what’s available now in the massive and restored Shaw DVD library. Consequently, apart from the work of King Hu, Chang Cheh, and Lau Kar-leong, PHK doesn’t deal with the very interesting output of the territory’s most famous company. Fortunately, Shaws has been carefully studied in the years since my book, in a massive volume from the Hong Kong Film Archive and in Poshek Fu’s China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema. For my part, this web essay and these blog entries try to make amends.

I could have recast PHK top to bottom, but I wasn’t convinced that I could come up something as pointed as the original. The text has been corrected, of course, and patches have been recast for greater clarity. It has also been enhanced by a few more examples, film sequences I referred to in passing but could not illustrate because I couldn’t find a print or couldn’t include color images. The chief updating is a series of sections added to the back end.

So here is what the book now looks like.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

The first chapter broaches the general idea of an aesthetic of popular cinema. There follows an interlude comparing Hong Kong and Hollywood, focusing on The Untouchables and Gun Men. Instead of launching into a general history of local cinema, Chapter 2 sketches some general features of the territory’s film culture, concentrating on its audiences and its critics. The following interlude,”Two Dragons,” talks about Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan, the two most famous Hong Kong heroes. Chapter 3 provides a condensed history of Hong Kong filmmaking up to 1997. The next chapter, “Once Upon a Time in the West,” traces how Hong Kong film attracted fans and festival prestige. There’s an interlude devoted to John Woo, then the fanboys’ demigod.

Chapter 5 surveys the industry, with emphasis on filmmakers’ craft traditions (how stories are planned, scenes are cut, and so on). The interlude that follows takes Tsui Hark as an instance of a director who creatively reworked such traditions. Chapters 6 and 7 go into the most detail about the aesthetics of Hong Kong film, surveying the dynamics of genre, the star system, visual style, and plot construction. Between these two chapters is sandwiched an interlude devoted to Wong Jing, the most disreputable major filmmaker in the territory. The longest chapter, the eighth, explores the distinctive aesthetic of action pictures, from martial arts to contemporary crime movies. The interlude that follows discusses three outstanding directors in the martial-arts tradition: Chang Cheh, Lau Kar-leung, and King Hu. The final chapter of the original book considers how the premises of popular cinema can be adapted to create “art films.” The principal, but not sole, example is the work of Wong Kar-wai. The original book concluded with an analysis of Chungking Express.

The new material in this edition starts with a chapter on changes in the film industry since 1997. That’s followed by an interlude focusing on the Infernal Affairs trilogy, which was as you know the source for The Departed. The next chapter considers how the artistic trends surveyed in the first edition have changed over the last ten years or so. While discussing developments in genre, storytelling, technology, and style, the chapter includes sections on Stephen Chow (particularly Shaolin Soccer and Kung-Fu Hustle), Wong Kar-wai (In the Mood for Love and 2046), and Johnnie To Kei-fung. The final interlude is a more in-depth discussion of To’s crime films and their relation to the indigenous action-movie tradition. At the very end is a new bibliography and endnote citations.

Readers not drawn to Hong Kong cinema might find my more general arguments of interest. For example, I suggest that Hong Kong shows us how important regional and diasporan networks are in creating and maintaining a film culture. To the claim that films reflect their societies, I reply that Hong Kong films suggest a different way to think about such a dynamic, using the model of cultural conversation. Readers interested in fandom should find something intriguing in the story of how cultists around the world helped establish Hong Kong film as a cool thing in the early 1990s. I also argue against the tendency in film studies to assume that when a film tradition doesn’t follow the rules of classical plot construction it must be based on something called “spectacle.” I suggest instead that we need to study principles of episodic plotting, which are probably quite common in popular art generally. In these and other areas, I wanted to use this cinema as a way into thinking about popular moviemaking as a whole.

After World War II, a tailor shop in Hong Kong put up a sign: “Reopening soon. Sooner if possible.” The same goes for me: Planet Hong Kong Redux is coming soon. Sooner if possible.

Here are some reviews of Planet Hong Kong by Richard Corliss in Time Asia (said I typed in my shorts with a beer at my elbow), Paul F. Duke in Variety (liked the book, worried that I talked like a Marxist), an anonymous writer in The Economist (said I’m a scholar who writes as a fan), Steve Erickson in Senses of Cinema (noticed my appreciation of stars), Mina Shin for Framework (developed my suggestions about festival culture), Leon Hunt in Scope (liked book, called me an empiricist, which tickles me down to my sense data), and Shelly Kraicer at chinesecinemas.org (as usual, more generous than he should be).

The most unexpected mention of the book seems to have vanished from the web. A New York critic who is surprisingly easy to outrage made an interesting attempt to charge me with synergistic marketing. He proposed, in the midst of a pan of Tsui Hark’s Time and Tide, that PHK was a covert attempt to promote Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, which had just won acclaim at Cannes. I wrote James Schamus, writer-producer of CTHD: “Now that we’ve been found out, we have to abandon our scheme to reprint my Dreyer book so as to coincide with Ang’s remake of Ordet.”

My quotation from Adorno may be apocryphal.

P.S. 13 December: Thanks to Daniel Erdman, I’ve now got the synergistic review mentioned above. It’s here. Thanks as well to Antti Alanen, who writes from Finland:

About ‘no time to be short’: quite possibly Adorno said so, and you are in good company:

Blaise Pascal: “Je n’ai fait celle-ci plus longue que parce que n’ai pas eu le loisir de la faire plus courte” (The Provincial Letters). J.W. von Goethe: »Da ich keine Zeit habe, dir einen kurzen Brief zu schreiben, schreibe ich dir einen langen« (letter to his sister Cornelia, but Goethe had apparently learned this from Cato and Cicero).

And soon after that came from Antti, Philippe Theophanidis wrote to point out the Pascal source as well. Once more I pay for the lack of a classical education!

Golden Scissors Part I (1963). Famous martial-arts choreographer and director Lau Kar-leung is on the far right. Source: Hong Kong Film Archive.

Rights to revert to author

In the Mood for Love.

DB here:

“They never tell you that.”

My neighbor Jim Cortada is a polymath. He joined IBM in the 1970s, when history Ph.D.s faced bleak prospects for academic jobs. Since then Jim has done everything from selling mainframes to leading seminars on quality management. As a business guru, he writes books on management strategy and tactics. He also writes both popular and academic books on the history of information technology. He finds time as well to write books on his grad-school specialty, Spanish diplomatic history.

Jim’s Amazon listing consists of fifty titles. He has worked with publishers as small as Lulu and as big as Oxford. So when he talks about the nuts and bolts of publishing, I listen. His reaction to what happened to me recently is as succinct as it as accurate: They never tell you that. Put into proper context, it’s good for young academics to keep in the back of their minds.

The Syndics speak, after prodding

14 Amazons.

Early this spring, when my royalty statement from Harvard University Press arrived, I noticed an anomaly. From early 2000 through the end of 2007, Planet Hong Kong had sold about 7000 copies. The average, about 800-900 copies a year, isn’t much for trade books, but fairly solid for an academic title. Perhaps courses on Hong Kong film were using it as a text.

But the newest royalty statement brought me up short. In calendar 2008, the sales dropped off the cliff. Harvard shifted only 85 paperback copies and virtually no hardcovers.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

Naturally, I blamed myself. People were losing interest, or the book wasn’t good enough to sustain an audience. But then I noticed that Amazon was offering the book only from third-party sellers. I checked Barnes & Noble and Harvard’s own website; both claimed to offer new copies. So I assumed that some long-term glitch at Amazon was leading to declining sales.

So about six weeks ago I tried contacting my editor at Harvard. Getting no email replies, I left phone messages. No response.

Mossbacks among you will recognize this as a danger sign. When an editor doesn’t reply, it’s not good news. So a call to Harvard’s editorial offices brought the promise of a prompt response. An email from a good-natured staff member there gave me the lowdown: Planet Hong Kong was being taken out of print. There were too many pictures to make a reprint edition worthwhile, someone had decided. Exactly when was that decision made? That matter was left vague, but I was told that the process of transferring rights to me had already begun.

Actually, I was a little surprised at that. Transferring rights back to the author is an old-media custom, but today, when “multiple platforms” are the new business model, there’s no reason for a book to go out of print. Publishers can keep selling a book through print-on-demand or in digital copies. Why Harvard’s decision-makers chose to revert the rights to me remains a bit of a mystery.

In any event, now the 2008 sales slump made sense. Only 85 copies of PHK were sold that year because in all likelihood Harvard, having decided not to reprint, was simply exhausting its stock of copies. On the basis of past performance, those sad 85 copies probably sold fairly early in the year, so there’s reason to think that the decision not to reprint was taken at some point in 2008, perhaps quite early. Yet I wasn’t informed of the decision until I inquired in 2009.

Nor am I complaining that I wasn’t consulted about the decision. Editors and press directors never tip their hand, for the very good reason that the author has no contractual say in the matter. And telling can only cause trouble, because authors have an annoying desire to keep their books in print.

In particular, academics relish prolonged disputation. If you’re told that your book might be headed for landfill, wouldn’t you launch an ambitious plea for reconsideration, complete with references to all the people you know who love the book and reminders that generations yet unborn will be eager to absorb your ideas? (Quotes from favorable reviews optional.) If tension rises, you can always murmur about feeble marketing efforts and a risibly high cover price. It could all get nasty, and the conclusion is foregone anyhow.

So when the publisher is mulling whether to drop your book, don’t expect to have a vote. But once the press has decided to drop it, why the reluctance to tell you?

I’m the one who’s supposed to kill my darlings

Shanghai Blues.

I’ve now had six books go out of print. Correspondence with regard to two of those, back in the 1970s, is lost in the mists of time. Of the four most recent instances, I was told many months after the decision was made, and by the most impersonal of letters—not from my acquisitions editor but from somebody in the cloisters of marketing or production. In the current Planet Hong Kong case, and in an earlier instance, I learned of the book’s fate only because I inquired. Who knows when I would have been told?

Nobody likes to give bad news, and university press staff members are unlikely to be flint-hearted business people. Editors are affable and solicitous; I’ve found them good company. They work long and hard on often fruitless projects: proposals that never turn into manuscripts; manuscripts that can’t get through the vetting process; manuscripts that fall hors de combat in editorial meetings.

And academic writers are almost sadistically inconsiderate. Once professors get their book contract, they behave like their students, trotting out excuses that they laugh about in the faculty pub. They ignore deadlines, word counts, permissions—in sum, everything they signed the contract to honor. Yet these antics are tolerated with remarkably good humor. If university book editors had a taste for blood, they’d be trade book editors. Or agents.

More broadly, it seems to me, university presses are under unique pressures. The good side is that they are a business that can’t go out of business. Even in hard times like these, a university press is unlikely to be shuttered. The blow in prestige and faculty morale would be severe. So most presses limp along. Since most of their costs are bound up in salaries, wages, and benefits, the only area that can feasibly be trimmed is marketing.

Furthermore, and too few young scholars realize this, every press plays a crucial role in the tenuring process. A humanities professor teaching in most universities and many colleges typically needs to publish at least one through-written book to support a case for tenure. There is thus a vast demand that some entity publish said books. The problem is that an academic can deftly write a book that virtually no one wants to read, let alone buy. So university presses are, in effect, subsidizing the tenure process.

Seen from this angle, university publishing is a system of reciprocal altruism. The University of West Overshoe Press publishes Professor Smith’s book on cultural resistance in Girl Scout parade floats. Professor Smith is thereby on his way to tenure at his school, the University of Rising Damp. At the same time, the URD Press publishes Professor Jones’ book on sexual transgression in Futurama. Professor Jones resides at Shattered Tibia State, whose press has just accepted a manuscript (on Wittgenstein’s use of prepositions in the Tractatus) from Professor Johnson. . . who teaches at the University of West Overshoe. I’ve abbreviated the cycle, but you can see that eventually, like the spirochete in Professor Pangloss’s song in Bernstein’s Candide, everything circles around. Any one university press is supporting employment at other universities.

So I’m entirely in sympathy with university presses. And the process, eccentric though it sometimes seems, can produce good books. But presses need to deal more straightforwardly and promptly with writers when a book’s fate has been decided. Jim Cortada is right. They never tell you that. But they should, and pronto. For then you can make plans.

Planet Hong Kong 2.0

Shaolin Soccer.

The lesson for young scholars is simple. Expect that your book will go out of print. Some books will pass over to print-on-demand or digital versions, but it doesn’t hurt to expect the worst. And a book can go out of print surprisingly fast. (The original British edition of my book on Ozu lasted only about two years.) You may learn of your work’s passing by accident, as I did, or through more direct notification, but you should think about your options.

You can simply let it go, accepting the press’s rationale that your book will remain available in libraries around the world for decades. Or you can wait for Google or Amazon to get around to digitizing your work.

Yet an out-of-print book is like a child limping home after a few rough encounters with the world. You might feel duty-bound to take care of it somehow. How?

First step in salvage is to make sure pre-print materials have not been destroyed. Most contracts require that these be returned to you if you regain the rights, but publishers, speedy in so little else, can dump physical production materials in the blink of an eye. In the old days, those materials usually consisted of rolls of thick celluloid, three or four feet wide and very long, on which the pages were printed like panels on a vast comic strip. (Several of these monsters lie pod-like in my basement.) But now most books are stored on computer files, often as PDFs. Copies of those should be returned to you.

Until recently, resuscitating your book came down to trying to find another publisher. I’ve had luck with this tactic only once, with The Cinema of Eisenstein—first published by The Syndics in 1994, yanked out of print in the early 2000s, brought back by Routledge in 2005. Republishing was always rare and is now nearly nonexistent; presses can’t afford to bring out a book that may have saturated its market.

Now, though, there’s another way to revive your sickly child.

For some years I’ve argued that most “tenure books” should be published only in digital form. But university presses have been reluctant to try such an idea, since an online book might not satisfy tenure committees. The best plan would be for some well-respected university press to lock in a vetting process for online publication as rigorous as any for print books. It seems that the University of Michigan Press has begun to do this. Once the model proves its value, and once problems of piracy are solved, the practice could catch on fast. For many books I own, I’d be happy to have PDF files on my computer. There should be big cost savings and, we hope, lower purchase prices—maybe even through selling separate chapters. Like music CDs, many books have only a few chapters you want. We can look forward to the iTune-izing of academic writing.

Yet if university presses need to be cautious about online publishing, the individual scholar doesn’t. The tactic is simple: Plan to put your out-of-print books on the Web.

Some authors may prefer to take existing PDF files or make new ones from the book’s pages, and add a fresh introduction. That’s essentially what Marcus Nornes and his colleagues helped me do with Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. We also tipped in new color images.

The alternative is to revise your book and post a second edition online. It’s a lot of work, but then you could probably charge something for it.

As for Planet Hong Kong, I’m still mulling my next step. Perhaps a publisher will be interested in a new edition, revised, corrected, and updated. Alternatively, I might prepare Planet Hong Kong for downloading on this site. Unlike the original, it could have color illustrations. I have to say that I find this option intriguing.

If you want a used copy of the old edition of PHK, about a dozen are available here. Once dealers learn it’s out of print, they may raise their prices. In any event, I hope to bring the book back in some form. Don’t say I didn’t tell you.

PTU.