Archive for the 'Poetics of cinema' Category

Manual labors

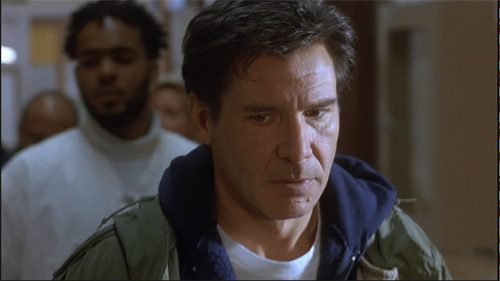

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

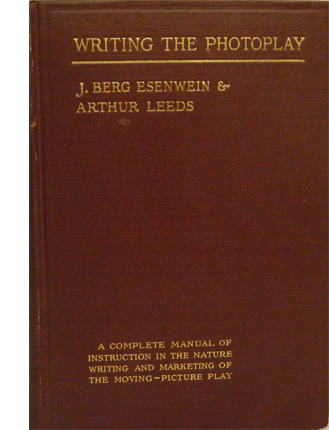

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

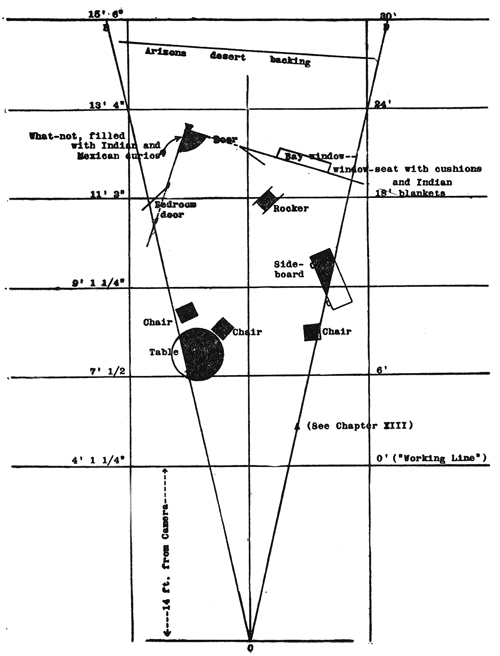

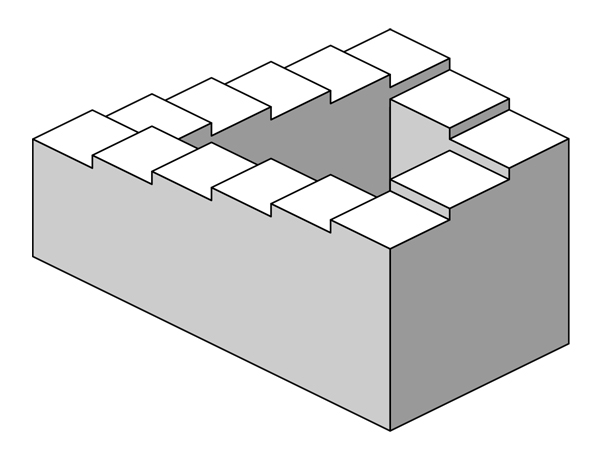

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

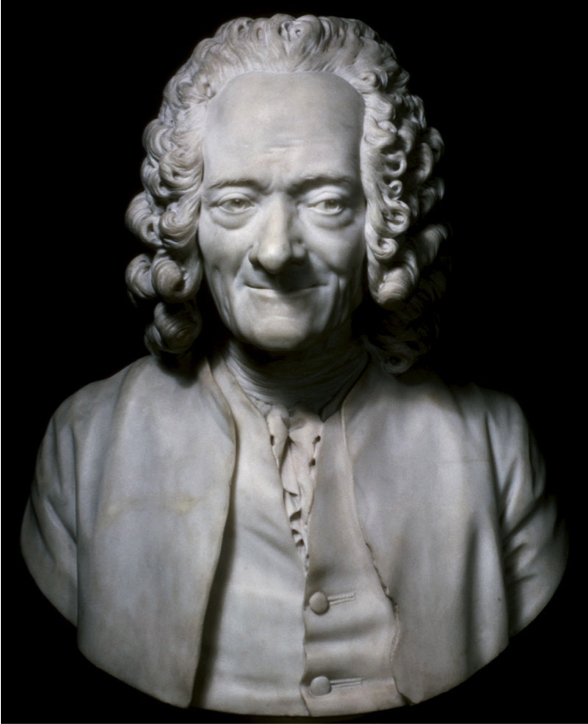

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

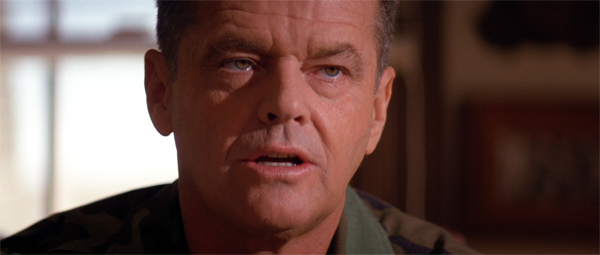

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

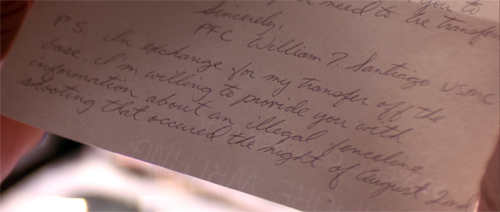

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.

This narration, shifting us from one group of characters to another, gives us a glimpse of the hidden story that the prosecutors need to uncover. The question will become not whether the officers overstepped their authority, but how they will be caught.

After A Few Good Men, we can see Sorkin’s cinematic career as exploring the creative space opened up in the 1990s, a space I’ve tried to map in The Way Hollywood Tells It and several blog entries. For one thing, there’s the matter of how to pick a protagonist.

It seems to me that the film version of A Few Good Men makes Kaffee the protagonist, with Joanne and Sam Weinberg as helpers–just as Jessep is the ultimate antagonist, with Kendrick as his helper. Centering on Kaffee and making him a gifted but glib and cocky young lawyer fits Cruise’s emerging star persona (Top Gun and The Color of Money of 1986, Cocktail of 1988). Sorkin has given us other single-protagonist plots, such as Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), and Steve Jobs (2015).

We may identify Sorkin more with ensemble, or multiple-protagonist, plots because of the fame of his TV shows Sports Night (1998-2000), The West Wing (1999–2006), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), and Newsroom (2014-1016). A long-form series permits constant shifting of the protagonist role across a season. But in feature films, I think, a genuine equality among several protagonists is more common in “network narratives” than in crowded films like The Women (1939) and Ocean’s 11 (2001). In the latter, there tends to be a “first among equals”: one or two main characters whose fates are most important, even if subplots centering on others are woven in. Such is the case, I’ll argue, with The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Scanning the menu

Molly’s Game (2017).

Sorkin’s preferred artistic strategies emerge even more clearly, I think, in his handling of narrative structure. He has more or less systematically surveyed a range of storytelling possibilities.

Politically liberal but narratively conservative, The American President (1995) presents an utterly linear plot. As in other romantic comedies, the central couple shares the protagonist role. Their relationships change as they make decisions and respond to external forces. The film plays out the familiar Hollywood double plotline of love versus work: political pragmatism threatens the President’s affair with a lobbyist for environmental reform. There are no flashbacks or fancy time-juggling, and the dialogue is classic flirtation, wisecrack, and one-upsmanship. The one “Fuck you!” becomes a shocking turning point, a test of friendship.

The crisis structure in The American President is presented as a race against time to line up support for two White House bills. Moneyball (2011) creates a comparable pressure on its protagonist. After his baseball team’s loss and the departure of his top players, Billy Beane faces the need to rebuild his roster for the new season. In a classic problem/solution plot layout, he finds a helper in statistician Peter Brand. Again, the plot is mostly linear, though interspersed with summary montages of sports coverage and brief flashbacks to Billy’s own failed ballplaying career.

The fragmentary flashback that carries its own mystery was a common technique of 1990s cinema (e.g., The Fugitive) and remains a standard tool of filmic storytelling. Sorkin’s films use it often, usually to gradually reveals what’s driving the protagonist’s struggle. A version of “continuous exposition,” the flashback allows deeper character revelation; it can liven up the more static sections of the film; and it can provide its own little mystery revelation. In the Moneyball flashbacks we see Billy recruited, decide to give up a college career, and then face failure. This shows how he could have empathy for the second-tier players who are cast aside–and whom Brand’s moneyball algorithms give a second chance.

The time structure is a little more complicated in Charlie Wilson’s War. Here Sorkin samples another option in the schema menu. The story’s crisis is over; the plot starts at the epilogue. After a credits-sequence montage, we’re taken to a CIA awards ceremony, at which Charlie Wilson is honored for working strenuously against the USSR for thirteen years. This scene turns out to be a frame around an extensive flashback.

What follows deflates this high-flown tribute, as we go back to 1980 and see the reprobate congressman pressured into helping the Afghan people by finagling clandestine US investment in fighting the occupying Soviet troops. Other subplots, including an investigation of Charlie’s partying ways, are interwoven. The long flashback concludes and the film’s final sequence returns to the ceremony, with a replay of a grinning Charlie getting his award. The ABA structure makes the whole public event a charade, underscored by a final title: “And then we fucked up the endgame.”

By contrast, Molly’s Game is more fragmentary. We start with a teenage Molly Bloom in a skiing competition qualifying for the Olympics, but an accident knocks her out of the running. This early passage is in turn interrupted by brief flashbacks to earlier in her childhood, of other competitions and accidents and recoveries, overseen by her demanding father. Her first-person voice-over fills in the background, echoing the fact that the story is drawn from the book she’s written (both in real life and in the film).

“None of this has anything to do with poker,” a title ironically informs us, but it’s a tease. This prologue, mixing scenes from phases of Molly’s girlhood, characterizes her as having tenacity, determination, and not a little rage at her dad. Then the present-day action starts, as usual at a crisis. Molly is wakened from sleep by the FBI arresting her for illegal gambling. What has happened in the meantime? Even after the scene of her arrest, the film’s narration wedges in a VHS interview with young Molly in which she’s asked about her goals.

The revelation of the formative years, saved for late in Moneyball, is put up front in Molly’s Game. But now there’s a mystery: How does a promising athlete become a gambling queen?

The question is answered through another series of time shifts, and these occupy the bulk of the film. After Molly’s arrest, the narration fills in her arrival in Los Angeles and her job working for a sleazy entrepreneur who arranges poker games for rich men. Her rise in the world of underground gambling is intercut with present-time scenes of her consulting an attorney to take her case–a risky proposition, since her customers include Russian mafia. And the alternation of her legal problems and her gambling career continue to be interrupted by flashbacks to her as a little girl, as a teenager, and as witness to her father’s infidelities.

Sorkin has layered his plot within several time zones: present, immediate past, and distant past, with the earliest one including scenes scrambled out of chronological order. Again, the purpose is to reveal character motivation. The flashbacks suggest sources of Molly’s decision to triumph over weak men–perhaps, it’s suggested, as revenge for her father’s mistreatment of her and her mother. The time jumps also reveal her as a fierce competitor unwilling to give in. Athletics, it turns out, has a lot to do with poker.

The network as character prism

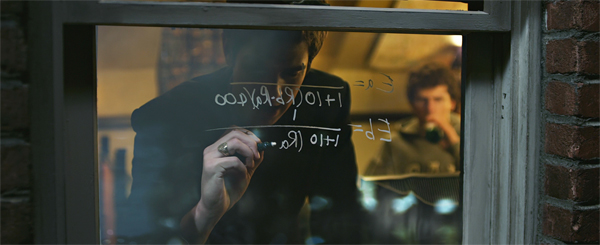

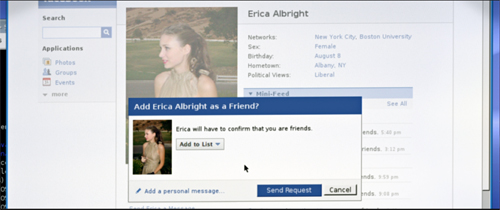

The Social Network (2010).

If there were a simple progress in Sorkin’s exploration of the menu of options, you’d expect that The Social Network would come later than it does. Yet before Molly’s Game yielded three principal time layers (the legal case, the career rise, the girlhood), Sorkin’s screenplay tracing the rise of Facebook had already fielded something more complicated than that.

Still trying variants, Sorkin this time puts the motivating moment, the incident that drives the character, at the front of the film. In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg is on a date with Erica Albright. His arrogance provokes her to break up with him. In a burst of pique, he turns a blog into a page that denounces her and asks readers to rate local women. With the reluctant help of his friend Eduardo Savarin, the site crashes the Harvard server and Mark faces disciplinary action.

At this point the film splits into more time-tracks, again transmitted through legal proceedings. The Harvard disciplinary hearing is filtered through a deposition responding to Eduardo’s lawsuit against Mark, long after their partnership has collapsed. Sorkin could have picked this testimony as his point of attack for opening the film, then flashed back to the origins of the suit. Instead, like Molly’s Game, The Social Network starts its plot in the past, skips ahead to the future, and then fills in more of the past.

A second lawsuit is in progress, this time from the Winklevoss twins, and a second string of deposition scenes. Apparently more or less simultaneous with the Eduardo sessions, these also anchor us in an approximate present and cue up incidents in the past. For instance, in a past scene, after an ally of the twins tells of Mark’s successful webpage, the narration cuts to the opening of the Winklevoss case’s depositions, and then back to the brothers recruiting Mark to work on their project.

The dual-track depositions in the present allow Sorkin not only to segue into illustrative scenes in the past, but also to set up crosstalk between the two lawsuits. Immediately after Mark dodges questions from the Winklevii, we see him dodge questions in Eduardo’s session.

By the 2000s, audiences trained in the time-shifting of the 1990s could follow these quick alternations. It’s also up to the director to keep us oriented through differences in costume, angle, lighting, color design, and other elements.

If you take the opening portion as what sets the narrative Now, you could call the deposition scenes flashforwards. Alternatively, you might consider those scenes as Now, although the opening orientation to them has been deleted. Either way, Sorkin has provided a flexible, dynamic structure that allows us to study Mark’s behavior and others’ responses to it.

One of the dreams of storytellers who embraced multiple-viewpoint plots was the idea of letting us see different, even contradictory facets of a character. The prospect was broached by Henry James (in his novel The Awkward Age) and Joseph Conrad (in Lord Jim, Chance, and other books). On the stage, Sophie Treadwell had experimented with it in The Eye of the Beholder (1919). Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles played with the possibility of such a “prismatic” narration in Citizen Kane, perhaps as a result of Mankiewicz’s unproduced play about John Dillinger.

By using the trial schema a storyteller can present a character’s public self-presentation, the impression management that tries to win adherence. But the fact that different people testify about a situation also offers prismatic possibilities. Here, the chief contrast is between Mark’s snotty recalcitrance at the counsel table and his swagger in the past.

During the film’s opening, when Mark confides in Erica and Eduardo, we’re about as close to penetrating his mind as we’ll get in the film. Later the film’s narration offers less a study in how his mind works than a portrait of how he handles people–his social survival strategies. The range runs from sheer bluster, as when he tries to overwhelm Erica, through awkward acceptance of class ambition when he meets the Winkleviii, to evasion, threats, and bumbling efforts at friendship. At the end, he goes flat and legalistic, telling Eduardo: “You signed the papers.” The film’s denouement arrives when Eduardo’s lawsuit is launched. “Lawyer up, asshole.”

The opening sections began in the past, but the ending leaves us hanging in the present. At a pause in Eduardo’s suit, the film concludes on the image of blank-faced Mark staring at his monitor. Isolated by his betrayal of the one person close enough to have been a friend, he’s checking Erica’s Facebook page.

This conclusion lets us imagine that sexual and romantic frustration, exposed in the opening, have reinforced Mark’s low-affect aggressiveness. It’s also a suggestion that his slightly vampirish predation suits him for the age of the social network. But we’ll never be sure, because his disdainful indifference is his armor against everyone he encounters.

As with Molly’s Game, this cluster of parallel timelines is intelligible and forceful as a revision of a schema (present/ past/ present) that we know well. And careful cutting, sound work, and performance have kept us on track throughout.

End to end control

Steve Jobs (2015).

In films that don’t rely on chases, fights, explosions, time travel, fantasy, or extraterrestrials, what can hold your interest? For one thing, snappy talk. The old theatre adage claims that dialogue needs to do one of three things: advance the action, delineate the characters, or add humor. Sorkin’s dialogue does all of them at once.

Steve Jobs is braced by his assistant Joanna while he frets over a press story.

“’The only thing Apple’s providing now is leadership in colors.’”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What does Bill Gates have against me?”

“I don’t know, you’re both out of your minds. Listen to me–”

“He dropped out of a better school than I dropped out of . . . but he is a tool bag and I’ll tell you why.”

“Make everything all right with Lisa.”

“You know–Joanna–boundaries.”

“You’ve come to my apartment at 1 AM and cleaned it, so tell me where the boundary is.”

“There, let’s say it’s there.”

“If I give you some real projections, will you promise not to repeat them from the stage?”

“What do you mean real projections? What have you been giving me?”

“Conservative projections.”

“Marketing’s been lying to me?”

“We’ve been managing expectations so that you don’t not.”

“What are the real projections?”

“We’re going to sell a million units in the first ninety days. Twenty thousand a month after that.”

Each reply shows that a strong line is like an arrow–feathered at the top, barbed at the tip. If your conflict is psychological, then the last part of the line should land with a punch. “We’ve been managing expectations so you don’t not.”

But the lines don’t exist in isolation. Every stretch of the film is a vivid lesson in whipping together bits of earlier conflicts, jumping from one to another as Jobs parries and ducks and changes the subject, all the while tension rises. One issue is picked up (Steve’s reaction to press coverage), interrupted by others (his rivalry with Gates, his friction with his daughter), followed up by a long-running relation with Joanna (“boundaries”), then a big piece of information: one goal, a sales target set in the first segment, has been achieved. But the others are left dangling, to be revisited, and we are looking forward to that.

This sort of repartee brings back the era of snappy chatter. The exchanges recall the films set in rehearsal halls (Footlight Parade), news offices (His Girl Friday), movie studios (Boy Meets Girl), gangster cafes (All Through the Night), and even a research institute (Ball of Fire). A few films of recent years, such as The Paper, successfully recapture the exhilaration of such fast, pungent dialogue. Sorkin delivers it consistently.

Steve Jobs is one of Sorkin’s most structurally ambitious projects. Here he tries out another menu item, that of block construction. In this layout, we get two or more marked-off chunks or chapters, sometimes without the same characters. Block construction came into fashion with Mystery Train (1989), Slacker (1990), and other indie works, and it remains a basic resource for Tarantino and Wes Anderson.

As ever, Sorkin rewrites the block premise as a drama convention, the division into spatially and temporally confined acts. The plot of Steve Jobs is organized around three public product launches: in 1984 (the Macintosh), 1988 (the NeXT Black Cube), and 1998 (the iMac). Each event teems with crises large and small, public and private. They’re all parallel, in that we see the few minutes of preparation leading up to the curtain-raising. Like a party or restaurant scene in a play, a product launch offers a confined space in which characters and story lines can mingle. The pressure of a product demo allows Sorkin to create deadlines and motivate many walk-and-talk passages through backstage corridors.

Just as theatrical is the flow of people into and out of Steve’s presence. From act to act the same associates are ushered into Steve’s presence: his former romantic partner Chrisann, his business partner Steve Wozniak, John Sculley, engineer Andy Hertzfeld, a journalist, and Lisa, the daughter that Steve is reluctant to acknowledge. The French phrase liaison des scènes, “scene linkage,” captures the way that within a single setting characters’ entrances and exits break the act into distinct pieces.

In addition, Sorkin doesn’t confine his time frame to the duration of the demos. As in other films, flashbacks interrupt the present. The 1984 segment uses only one flashback, a visit to garage-hacking days that sets up the dispute about open and close architecture. The flashbacks thicken in the second segment, which reveals the conflict that led Steve to break off with Sculley. That quarrel in the past is tightly crosscut with their confrontation in the present, and as the tension builds one man in the present is replying to an objection in the past. This rapid pacing is one way a “theatrical” premise can hold an audience accustomed to action movies.

Like Fincher’s intercut depositions in The Social Network, Danny Boyle’s handling keeps us oriented through staging, costume, color, lighting, and shot/ reverse shot eyelines.

The block most saturated with flashbacks is the third, the one launching the computer that brought Apple to marketplace triumph. This chapter incorporates glimpses of scenes shown in the first two segments, along with revelations of Steve’s first approach to Sculley. This last recollection is prompted by his admission that he long ago found the biological father who gave him up for adoption. (Many of Sorkin’s protagonists have Daddy Issues.) Again, a big revelation about character motivation is saved for a flashback late in the film.

In addition, other crises come to a head. Steve appears to break definitively with Wozniak, and he reconciles with Lisa, whom he hasn’t, after all these years, fully taken into his life. As he achieves his goals–a successful computer at last, a settling with Wozniak and Andy, and a tentative accceptance of Lisa–he displays more chastened and cautious behavior. He has admitted his fallibility (he was wrong about the Time cover), he has realized what he lost in challenging and trashing Sculley, and he’s ready to move to the next challenge (“music in your pocket”). True, he treats Woz brutally, but Woz gets the final word: “It’s not binary. You can be gifted and decent at the same time.” Steve doesn’t change completely; he just gets a bit more human.

Interestingly, these cadences fit the four-part structure that Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood has revealed governing many classical plots: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax, followed by an epilogue or tag. Sorkin has “cinematized” his three “acts” by letting the final one harbor Development, Climax, and an epilogue.

Kristin also points out that classical film story telling relies on motifs that weave their way through the film. Not only music but lines of dialogue and images recur to point up repeated actions, indicate changes in character, or add humor. (A running gag is a comic motif.) Yet movies didn’t invent this tactic. Novels, poems, and plays rely on recurring motifs. Macbeth circulates imagery of blood and ill-fitting garments, while The Importance of Being Earnest wrings a lot out of the mysterious word “Bunbury.”

Steve Jobs is packed with motifs, far more than most movies I can think of. Some bounce around one segment and into another, and several come back at intervals in all three. All the characters relitigate old complaints, and Steve masterfully deflects a conversation by returning to remarks he’s made before. Here’s a partial list of items that are recycled again and again.

Starting exactly on time, the controversial SuperBowl ad, the need to turn off the Exit signs, a bottle of ’55 Margot, the Time cover, the purported treachery of Dan Kottke, “a million in the first 90 days,” “I don’t have a daughter,” 28%, Woz’s request to acknowledge the Apple II, “playing the orchestra,” closed versus open systems, the name Lisa, “end to end control,” 2001, “a dent in the universe,” slots, Pepsi, the psychology of adopted kids, “You get a pass,” the threat of a press release, and “which Andy?”

For Sorkin, even “Fuck you” becomes a motif rather than a space-filler.

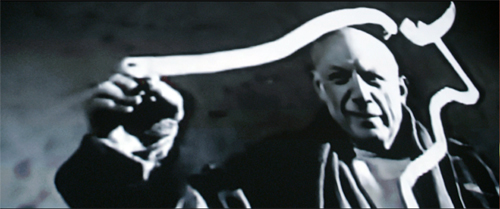

A significant cluster involves the arts, particularly music and painting. In their quarrel the two Steves compare themselves to the Beatles, and Bob Dylan’s image and songs float through the movie. This association with the arts helps offset the unpleasant side of Jobs’ temperament, his crisp, frosty bullying of others and his relentless imposition of his “reality distortion field.”

Another motif softens him a bit: his desire to bring computing to kids. The prologue, in which Arthur C. Clarke is interviewed about the future of computing, sets up several motifs–the idea of separating oneself from others (Steve in a nutshell), the importance of home (associated with Chrisann’s demands), and particularly childhood. The reporter interviewing Clarke has brought his boy along, and they discuss how a new generation will quickly grasp the power of personal computing.

That motif is dramatized when, at first indifferent to five-year-old Lisa, Steve uses her as a demo to show Chrisann what the Mac can do. But his interest rises when Lisa intuitively understands that she can draw with it. “Lisa made a painting on the Mac,” he says thoughtfully. He seems to realize that she could be his brainy daughter, and he resolves to put her in a good school. Her drawing looks forward to Picasso’s swooping dab at a bull in the climactic montage of the 1998 launch.

The ping-ponging motifs are mostly in the dialogue, though. They push the action forward, recall earlier moments, and characterize the combatants while also yielding some laughs. Above all, the motifs chart Jobs’ character arc. We know that he’s more committed to Lisa at the end when he breaks his routine and says he’s willing to start the performance late. Soon he will reveal that he has saved her painting to give to her.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I call Jerry Maguire a “hyperclassical” movie–more classical than it needs to be, flaunting a virtuosity of construction and motivic echo. I vote for Steve Jobs as another instance. Sorkin has used cinema to multiply motifs to a higher power.

Exporting ideas across state lines

The Trial of the Chicago 7.

One innovation of turn-the-century-theatre was the so-called “drama of ideas” or “problem play.” Ibsen, John Galsworthy, and Bernard Shaw sought to break away from standard intrigues of mystery and romance in order to dramatize women’s rights, labor struggles, and other social issues. Sorkin, with his liberal political bent, has brought that legacy to his film work. The subjects and themes he tackles have become as distinctive a marker of his work as any strategies of form and style.To be more precise, his formal and stylistic strategies work upon the ideas he wants to put forth.

How much private life is a US President entitled to? What is the duty of a politician who wants to enact social change? For a tech entrepreneur, where does idealism end and domination begin? Why should a woman not be able to compete on equal terms with men? Does social change come best through reform (reason, the ballot box) or revolution (change of consciousness)? Something like this last occupies him in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The problem at the center of the film is: How to protest, and eventually stop, US involvement in the Vietnam war? The film’s prologue and epilogue announce the sweep of the issue. It begins with President Johnson ramping up troop commitments and establishing the draft lottery, all during a wave of assassinations. The film ends with Tom Hayden reading out the names of troops who have died while the trial was dragging on. Early on, Rennie Davis establishes the list because it’s “who this is about.”

The defendants in the trial are only loosely associated. Bobby Seale doesn’t know the others and was in Chicago just four hours; he’s also denied counsel. Sorkin carves out two major factions. Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, as student activists out of SDS, are presented as preppy intellectuals, committed to antiwar action within the frame of protest and legal debate. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, associated with the Yippies, are countercultural provocateurs. They anticipate a spectacle of innocence attacked by those in power. They will show the Chicago Democratic convention to be staged, as Walter Cronkite says at the end of the opening montage, in “a police state.”

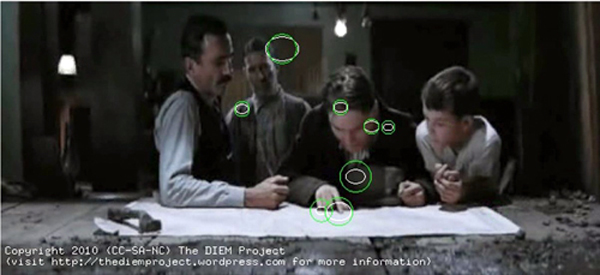

Although Tom’s and Abbie’s factions communicate a little before the events, it’s the pressure of circumstances in Grant Park that pushes them into dispute. Alongside them Sorkin develops subplots that suggest other political alignments. David Dellenger’s commitment to nonviolence is tested by the flagrant repression of Bobby Seale. Richard Schultz goes along with orders to prosecute, knowing that the case is trumped up. Jerry Rubin falls briefly in love with an undercover policewoman. Fred Hampton tries to help Seale, only to be killed. Attorney William Kunstler discovers that he has a surprise witness to call. Editor Richard Baumgarten notes that in cutting all these lines of action together: “I feel like one of the great successes of how this film unfolds is that each of the characters does have a moment, or multiple moments.”

Tom and Abbie emerge as the “first among equals” because they most sharply articulate alternative accounts of what they’re facing. They aren’t dual protagonists, like a romantic couple tackling common problems. They’re at odds throughout. On the first day when Tom tries to get agreement on goals, Abbie challenges him.

Early court scenes show Tom annoyed by Abbie’s antics, but neither is really an antagonist for the other. Tom can half-humorously admit that he got a haircut to impress the judge, and clearly Abbie admires Tom. The antagonists are the government prosecutors and Judge Hoffman. Tom and Abbie function as what Kristin calls parallel protagonists. Like Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus, or Captain Ramius and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October, they are at once opposed to one another and fascinated by each other. They both compete and cooperate.

What does each one want? This will become part of the drama’s problem, because the two men will be charged with coming to Chicago to stir up violence. Sorkin shrewdly postpones the question in the opening montage that brings some main players together through crosscutting. Incomplete dialogue hooks make their goals somewhat mysterious.

Tom: Young people will go to Chicago to show our solidarity, to show our disgust, but most importantly–

Abbie: –to get laid by someone you just met. . . .We’re going peacefully, but if we’re met there with violence, you better believe we’re gonna meet that violence with–

Dellenger: –non-violence. Always non-violence and that’s without exception. . . . (asking his son what to do in the face of police:)

Dellenger’s son: Very calmly and very politely–

Bobby Seale: –Fuck the motherfuckers up!

Seale’s capper would seem to negate the nonviolence of Dellenger’s position, but at the end of the montage Bobby refuses the pistol his colleague Sandra offers him. “If I knew how to use that, I wouldn’t need to make speeches.”

Unlike Dellenger, he’ll hit back if attacked first. So now only the positions of Tom and Abbie remain undefined.

Eventually, Tom exposes his rationale. If they can prove they were peaceful demonstrators within their rights, it will help “to end the war and not fuck around.” That demands treating the trial seriously. “We as a generation are serious people.” And he doesn’t want to raise police culpability. “We’re protesting the war, not the cops.”

From the start Abbie insists that the trial isn’t a matter of law but of contingency. “This is a political trial.” They were chosen to be examples, and the two lesser defendants are “give-backs,” people the jury can let off with a clear conscience. Abbie and Jerry came to Chicago knowing that police violence was very likely. (Cronkite said so too.) The best way to prove state oppression is to lay it bare, preferably with gonzo humor. After all, the whole world is watching.

The film’s structure supports Abbie’s analysis. Sorkin’s narration, using a moving-spotlight approach, has from the start tipped us that Attorney General John Mitchell has ordered Schultz to prosecute the 7 on flimsy grounds. Mitchell, a spiteful conservative, wants to crush antiwar protest, but he’s also petty. He’s miffed that Johnson’s AG Ramsey Clark insulted him on the way out of office. Mitchell has assembled a mixed bag of antiwar activists to charge with conspiracy. (In an ironic twist, they conspire most successfully after they have been thrown together for trial.)

So the problem play becomes a progress toward understanding political power. Tom Hayden (and to a lesser degree Kunstler) come to grasp the reality of an engineered police provocation and a show trial. Abbie’s privileged insight is further stressed by the fact that he’s the only character given a narrator role. Sorkin interrupts the trial with shots of Abbie at a mike in a club, telling the story of the fights during the riots, correcting the false testimony of the cops. In stage tradition, Abbie is the raisonneur, the explainer.

The conflict between Tom and Abbie gets specified gradually, sharpened in strategy sessions where Tom berates the Yippie contingent for clowning. If progressive politics is branded as childishness, “We’ll lose elections.” Abbie calmly replies that “We’re going to jail for who we are.” The debates are about tactics as well. Tom wants the demonstration to keep away from the convention hall, while Abbie insists that they go downtown. As it turns out, the police squeeze them out of the park and force them into a trap that yields the spectacle that Abbie and Jerry anticipated.

Through crosscutting Sorkin again creates several layers of time: the runup to the convention, the protests themselves, the trial, and a more unspecified moment when Abbie is at the microphone narrating. More linear than the time mosaics of Molly’s Game and Steve Jobs, the Chicago 7 array might seem a step back toward the classic trial schema. Basically, the court proceedings frame the flashbacks to the purported crimes.

The relative linearity is needed, however, to allow us to chart the progress of the parallel protagonists. In a neat balancing act, Sorkin dramatizes character change with Tom Hayden and character revelation with Abbie Hoffman.

Hayden’s character arc traces his realization that the trial is rigged. He has brought table manners to a revolution. He presents a wholesome appearance, and when pressed by Bobby he half-admits he’s rebelling against his upbringing. (Daddy Issues again.) Even his “reflex” action of rising when His Honor enters, violating the pact among the 7, shows that the impulse to behave well is struggling against his sincere urge to end the war through citizen action.

Yet Tom has an outlaw side as well. He releases the air from the tire of a cop car to allow Rennie to escape surveillance. At the climax, seeing Rennie beaten, he calls for blood to flow through the city–not, he tries to explain, the blood of others, but the blood freely given by the protesters. Still, he joins forces with Abbie, Jerry, and Dellenger as they are lured onto the footbridge and into the cops’ trap. The cops, having choreographed the street assembly, push them through the tavern window.

Tom, our main viewpoint vessel in the film, also visits Ramsey Clark with his attorneys. It’s then that he realizes the trial is Mitchell’s political charade aiming to override Clark’s decision not to prosecute the demonstrators. So, after Clark has testified (and sees his testimony suppressed by Judge Hoffman), Tom can redeem himself.

Judge Hoffman has offered Tom clemency before he makes his final statement. The good boy who had asked, “Why antagonize the judge?” rises in polite defiance to read the names of the dead. He will take the same punishment meted out to the others. He now understands revolution as spectacle.

So there’s a little of Abbie in Tom. In the same final stretches of the film, we learn that there’s a little of Tom in Abbie. Tom had planned to testify, but he can’t justify what he said on tape. So Abbie takes the stand. His slapstick persona drops. Behind the Jewish Afro and the wisecracks is revealed an intellectual who can quote the New Testament and gently praise Tom as a patriot. Schultz questions him: Was he hoping for a confrontation with the police? “I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.”

As in the opening montage, Sorkin cuts away before Abbie answers, and his pause and grave demeanor let us consider that for all his bravado, he has regrets about the crisis he saw coming.

Like any problem play, The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be criticized for stacking the deck, or oversimplifying, or recasting the problem in ways that favor certain interests (e.g., white college-educated men). But that critique is the risk artists run all the time, even in the most anodyne “nonpolitical” work. If critics study how films achieve their effects, viewers can be more aware of how the schemas we know are shaped by the movies we see and get a clearer sense of means and ends, purposes and fulfillment.

At the same time, artisanal skill in a robust tradition is intrinsically worth analysis. That analysis can reveal new possibilities in what cinema can do. In The Trial of the Chicago 7 Sorkin creates a dramaturgy that embodies ideas in characters’ conflicts, changes, and hidden facets. Once more a theatrical premise has been turned into classically constructed cinema. Sorkin’s work offers one way that this tradition can stay fresh–not through shocking breakthroughs but by highly skilled reworking of schemas accessible to a broad audience. You know, the way theatre used to be.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin and Jeff Smith, who helped me clarify my ideas.

For more background on this sort of narrative analysis, there’s a synoptic blog entry here. This earlier one might also be of use. Rory Kelly offers some nuanced analysis of the Hollywood character arc.

Cinema’s debts to theatre are considered in this entry, and some others in the category Film and other media. On the power of artisanal care, there’s this on Buster Scruggs.

Another entry discusses how actors use their faces in The Social Network.

P. S. 5 March 2021: I’ve just found some interesting remarks from Sorkin about what he calls “the puppy crate”–the need to focus a drama in a confined time and space. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is an obvious example, but so too is Steve Jobs. “I need four walls really badly.”

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

Mirror neurons and cinema: Further discussion

The Fugitive (1993).

DB here:

How do we respond to films? How are they designed to have effects on us? How do our responses outrun the “programmed” effects filmmakers aim to create?

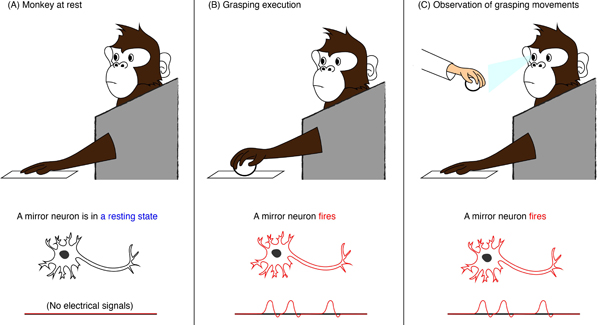

These are perennial questions of film studies. Since the 1990s, neuroscientists have tried mapping our brains’ reactions to moving images, and one school of thought in that tradition has sought answers in the phenomenon of mirror neurons.

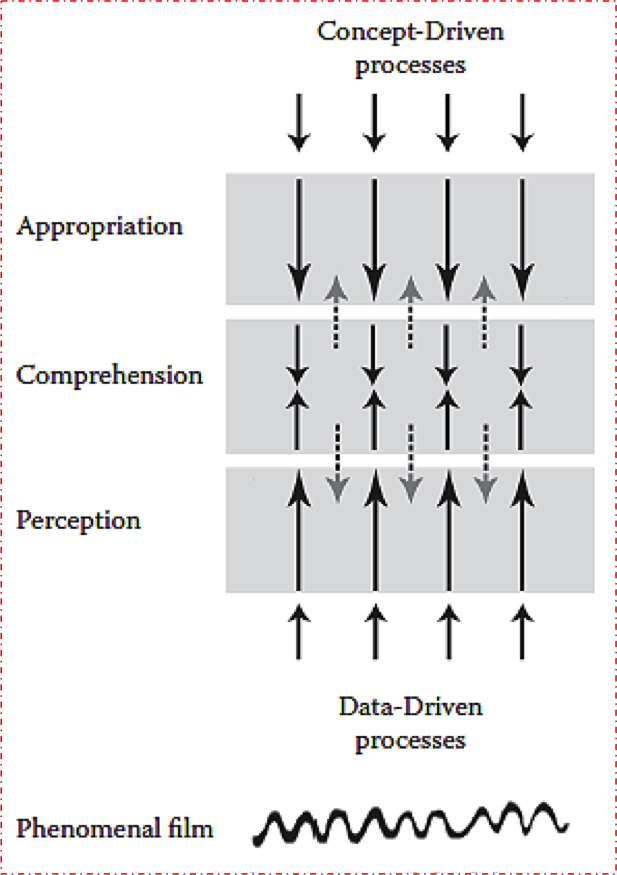

In my spring seminar, I tried to introduce students to a bit of this debate. First I laid out what I’ve taken to be the most useful psychological findings for my research–what has been known as “classic cognitivism,” stemming from the New Look psychology of the 1950s and 1960s.

At the same time I wanted the group to consider alternative theories, and the timing of the book The Empathic Screen, by Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra, seemed propitious. In addition, I learned of Malcolm Turvey’s response to their research and brought that essay to the seminar. For some years Malcolm has been advising caution about importing scientific research into humanistic studies generally and film studies in particular.

Because of the coronavirus, our seminar had to meet online, so I prepared an online text version of my planned lecture. One advantage of that was that I could get very long-winded about things. But it also meant I could post a shorter prepublication version of Malcolm’s essay on the subject. And remote access brought him into the seminar to make his case when we met.

I invited a response from Vittorio and Michele, and they duly sent one along. It is published here, followed by comments from Malcolm and me.

If you haven’t read my initial entry or Malcolm’s, I hope you will try before you read what follows. (Just homework; they won’t be on the final.) If you saw them at the time, a quick look back should suffice.

And yes, The Fugitive is involved. Eventually.

The Neuroscience of film: A reply to David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, and a contribution to further the debate

Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra

The contribution cognitive neuroscience can offer to film studies and in a broader perspective to the debate within the humanities is at the same time potentially priceless and to be carefully evaluated. Still in its early infancy, the field of “neurohumanities” represents a great challenge to a new way of thinking our relationship with the mediated worlds of the arts. In the last twenty years, more or less, we have been observing a very productive exchange between psychologists, cognitive scientists, neuroscientists and scholars from literature, theater, art, music, dance, and cinema, aiming to develop what Shaun Gallagher would call a “critical neuroscience”, suitable to inform a critical theory about the role our brain-body system plays in our aesthetic experiences.

What is at stake here is, on the one hand, the relevance of these experiences in our lives, the nature of our being “storytelling animals” (to borrow Jonathan Gottschall’s definition), both when we produce stories and when we play the role of readers or viewers, and the updating of our embodied relationship with the simulated worlds of the arts and the technologies we live in and through. On the other hand, we are facing a fascinating challenge for theory, in our case film theory, where words like action, interaction, empathy, intersubjectivity, we have been using for years within our fields of study, have to be reconsidered after the neuroscientific discoveries of the last decades.

The idea both of us shared at the beginning of the research that has brought us to perform experiments on cinema, to test the role of motor cognition during film watching and then to the publication of our book The Empathic Screen. Cinema and Neuroscience, was – and still is – that the contribution of cognitive neuroscience is first of all theoretical, as the one of psychology or cognitive science has been within the humanities, and then empirical, trying to shape, step by step, a new proposal to study parts of our film experience, which can confirm, renew, or in some cases overturn our ideas.

We know that the debate is still oscillating between two positions which we could, just to be clear and simple, describe as “neuromaniac” and “neurophobic”, where in the first case the risk is seeing neuroscience as the right place for explaining and clarifying the secret of life, while in the second case the risk is not seeing the productivity of a confrontation with its theories and empirical findings. David Bordwell’s and Malcolm Turvey’s entries on David’s blog about this topic and our book are a relevant sign of the need of debating about neuroscience and film, and we are confident that the next chances for exchange – the film journal Projections is going to schedule an issue to host part of this debate – will widen the discussion, involving scholars with different and enriching positions.

What we would like to do here, as a short reply to some of David’s and Malcolm’s observations, is to put forward three lines for reflection that we consider methodologically important to carry on the debate facing directly the core of the matter, and that guided the writing of The Empathic Screen. First of all, we want to say something about what we mean when we say “neuroscience”, what neurons can do and what they cannot, until where neuroscience can talk, and where it has to stop and leave room to theory and to ideas for new research within this open minded new field. Secondly, we have to ask ourselves which kind of film theory can host such a new debate, how it can converse with the main theories that have been taking the field in the last decades, and how we can think of teams and groups of research able to develop the critical neuroscience we need. Lastly, we would like to say something about why it is important to do experiments, what a serious experiment can give us, and what is its function for the debate (on this point, the abovementioned entries already said something).

1) Critical Neuroscience. It is hardly disputable that there cannot be any mental life without the brain. More controversial is whether the level of description offered by the brain is also sufficient to provide a thorough and biologically plausible account of social cognition – and of aesthetic experience. We think it isn’t. Such assertion is based on two arguments: the first one deals with the often overlooked intrinsic limitations of the approach adopting the brain level of description, particularly when the brain is considered detached from the body, or when its intimate relation with the body and the contextualized relation the body entertains with the world are neglected. The second argument deals with social cognitive neuroscience’s current prevalent explanatory objectives and contents, in many quarters still dominated by the logocentric solipsism heralded by classic cognitivism. As we wrote in the book, we think that “neuroscience can offer a genuine contribution to the re-definition and comprehension on new empirical grounds of fundamental and paradigmatic themes of the human condition, such as the perception of images and the construction of our network of relations with objects and other human beings.

Action, perception and cognition are terms and concepts describing different modalities which are permanently bound by the embodied and relational essence of all living beings, including humans.” In that respect, some theoretical premises David Bordwell cites, like the modular mind as proposed by the analytic philosopher Jerry Fodor, are patently contradicted by neuroscientific research. At the same time, to quote our book again, “If the neuroscientific approach to cinema [proposed in this book] is to be applied successfully, it must be critical, its potential and its heuristic limitations must be clear, it must be open to dialogue and constructive collaboration with other disciplines such as the history of cinema and the theory of film, philosophy and other fields of studies.” Neurosciences are aptly declined in the plural, because in spite of the same basic methodological approaches and methodologies, the questions neuroscientists ask and the answers they are seeking by applying those approaches and methodologies can be incredibly different.

In the last thirty years or so, when investigating human social cognition cognitive neuroscience has mainly tried to locate the abovementioned cognitive modules in the human brain. Such an approach suffers from ontological reductionism, because it reifies human subjectivity and intersubjectivity within a mass of neurons variously distributed in the brain. This ontological reductionism chooses as level of description the activation of segregated cerebral areas or, at best, the activation of circuits that connect different areas and regions of the brain. However, if brain imaging is not backed up by a detailed phenomenological analysis of the perceptual, motor and cognitive processes that it aims to study and – even more importantly – if the results are not interpreted on the basis of the comparative study of the activity of single neurons in animal models, and the study of clinical patients, cognitive neuroscience, when exclusively consisting in brain imaging loses much of its heuristic power and reduces to a 2.0 version of phrenology.

It should be added that the competence of understanding others -real people as well as fictional character- is uniquely describable at the personal level, and therefore is not entirely reducible to the sub-personal activation of neural networks in the brain, hypothetically specialized in mind-reading, as too many neuroscientists nowadays think. Indeed, neurons are not epistemic agents. The only things neurons “know” about the world are the ions constantly flowing through their membranes. Thus, we think that the final goal of cognitive neuroscience should be to profitably and personally conjugate the experiential dimension through a study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain, by its neurons, and by the body. A cognitive archeology that can successfully integrate our knowledge of the personal level of our experiences.

2) Film theory. For what concerns its theoretical contribution to film studies, our position in The Empathic Screen is that cognitive neuroscience can play a role in the study of spectatorship, film style, and the analysis of new devices and the ways we interact with them. Obviously these aspects are strongly intertwined, as when we study the effects of camera movements on motor cortex activation (in one out of the six chapters of the book) we are, for instance, already studying the viewer’s basic response and his or her motor involvement during film watching, the impact of some stylistic elements on film composition, and the evolution of these movements in new aesthetic forms like those implied by an action camera, or a drone (this is also the reason why we decided to dedicate the last chapter of the book to the matter of new mediations provided by the screens of our laptops, smartphones, and the like).

Though David wrote that our book is “the fullest account” of mirror neurons application to cinema, we think that it would be more correct to say that The Empathic Screen is perhaps the fullest account of the application of embodied simulation (ES) theory to film studies. Basically, this is what we have been working on since 2012, when a first theoretical article (“Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies”) appeared in Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image, and then when we presented and discussed the outcomes of our three film experiments in the Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, Cognitive Science, and PloS One. Of course, ES relies on the discovery of mirror neurons, but as it has been demonstrated in an articulated debate which has gone through philosophy, aesthetics, psychology, psychoanalysis, linguistics, and the arts, ES theory goes beyond the (scientifically proved) action and functioning of mirror neurons to enter the discussion on the role our brain-body system plays when it is engaged in real life and virtual environments.

We found that the questions raised by ES theory had been to some extent anticipated by the first physiological studies on film between the 1910s and 1920s (with relevant examples in Italy and France), and the almost coeval American literature on the didactics of cinema, where people like Epes Winthrop Sargent, Henry Albert Phillips, or Victor Oscar Freeburg focused both on “action” as the basis for film style and cinematic intersubjectivity, and the idea that the response of our senses to film movement, like to any physical movement, takes place before we have time to interpret the dramatic significance of the visible stimulus. Of course, as argued in our book, we do not think that film experience could be explained just focusing on action and the viewer’s responses to motor stimuli, but we think that film cognition should not ignore the role of motor cognition, and unfortunately this is what happened till now with few exceptions (the more noticeable back in the 1920s, then in the ambitious season of French filmology, and in some notes by Maurice Merleau-Ponty for a 1953 course at the Collège de France). Neuroscience can provide inspiration to explore this field, and it can also provide new methodologies to support theories and to update and problematize some of them.

Sometimes the most skeptical scholars say that neuroscience when applied to arts, tells us nothing new, or just already expected things. Obviously, we could say the same of semiotics, phenomenology, or cognitive science, but this is not the point. We do not need just “new things”, or new data, we need theories capable of raising more questions, of articulating and inspiring new lines of research, of shedding light again on neglected topics. Otherwise we would fall in the trap of expecting the definitive answers from the study of the brain. As we wrote in the Introduction to the book, our goal was “to present a study of film starting from the sensorimotor and affective implications, identifying a series of neurophysiological mechanisms as a tool for the deconstruction and comprehension of the conceptual instruments usually adopted in debates on the various aspects of cinema.” From this perspective Murray Smith, in his Foreword, emphasizes very well our pluralist approach across the history of film theory, putting forward the strong proposal of a new conjugation of the experiential dimension of cinema with the study of the underlying sub-personal processes and mechanisms expressed by the brain-body. It is from here that a discussion has to start. To us, it is not useful to give up such a complex and enriching debate taking a pessimistic position that does not consider the complete scientific debate behind ES theory. The history of film theory, from the classical period to the present, has greatly profited of the confrontation with science, even when some insightful observations came from very debated arguments (sometimes not confirmed arguments, unlike the case of mirror neurons). This doesn’t mean that we have to ignore the debate around scientific matters, but that we have to cope differently and more profoundly with the science on the theories we propose and discuss, not being “optimistic” or “pessimistic” (read, in this case, neuromaniac or neurophobic), but just informed and critical.

3) Experiments. In his essay David Bordwell wrote “my model of the spectator is agnostic about how the processes are instantiated in physical stuff. Doubtless retinas and neurons and inner ears and the nervous system are involved, but I’m not providing the details. I have no idea how to do so.” Neuroscientific experiments, as those described in The Empathic Screen, aim to shed light upon the contribution of the brain-body to our relationship with films. As we wrote in the book, “What appears on the screen, the ways and means, the strategies of appearance in cinema are the result of the direct relationship our perceptual system has with technology and are influenced by production processes and needs that consolidate the social aspects.” The naturalization of mediated forms of intersubjectivity, such as the experience of film, should start from the deconstruction and reconfiguration of the concepts that we normally use to describe it, by literally studying their component parts and where they come from through the experimental approach of investigation and the level of description of the brain-body system allowed by neuroscience.

To that purpose, we decided to start investigating some important elements of film style, whose intrinsic performative character is betrayed by its etymology from the Latin stilus, the ancient writing tool. We did so by focusing on some constitutive elements of what does it mean to perceive a film: camera movements and montage, which filmmakers employ to modulate spectators’ engagement and possibly intensify it. We decided to side with what many filmmakers do, that is, conceiving of style from a bottom-up perspective, concerned with the perception of film and the ways to calibrate what the spectators see. We should add that our take on visual perception, hence on film perception, parts from the standard account of vision as the mere expression of the visual part of the brain. To the contrary, evidence shows that vision is multimodal, as it encompasses the activation of motor-, tactile- and emotion-related brain circuits.

The experiments on camera movements described in The Empathic Screen, kindly discussed by David Bordwell and Malcolm Turvey, were originated by the idea that it is possible to test whether and to which extent spectators’ bodily perception of the film can be partly determined by their simulation of camera movements. The rationale being that the more these movements mimic human bodily movements –as with the Steadicam– the more they activate motor simulation in spectators’ brains, hence intensifying their reactions to them.

Thus, in the first experiment we correlated the electroencephalographic activation of spectators’ brains during the observation of clips showing an actor performing hand actions shot with a still camera, zoom lens, dolly and Steadicam with their explicit rating of engagement with the same clips. The results showed that clips shot with the Steadicam evoked the strongest motor simulation and correlated with the most intense perception of camera movements’ resemblance of realistic bodily movements and identification with the filmed actor (see Heimann et al., 2014).

In the second experiment the same rationale was used to test what happens when the different camera movements film an empty room. Once more, and in spite of the total lack of filmed bodily actions, the spectators’ brains showed the strongest motor simulation when perceiving clips shot with the Steadicam. In this experiment, we added some open questions to further explore the spectators’ phenomenal experience of the observed film clips: the results showed that the Steadicam induced the strongest motor simulation and led the participants to feel like walking together with the camera’s eye (see Heimann et al., 2019).

Taken together, these two pioneering experiment show for the first time that the Steadicam’s power of bringing the audience literally into the scene is related to its capacity to trigger stronger motor simulation and stronger feelings of engagement than all the other tested camera movements. We never claimed that spectators’ whole film engagement amounts to simulating camera movements. We argued that, “If film has something to do with subjectivity, it is to the extent that its moving form bears the imprint of a subjectivity”, as posited by Dominique Chateau, our two experiments provide empirical support to the idea that the intersubjectivity instantiated by film can be profitably studied by focusing on the ‘motor cognition’ stimulated in spectators by the film techniques employed. Furthermore, we think that our results can also offer a valid contribution to the debate within film studies on the supposed lack of subjectivity of the Steadicam, as argued by Jean-Pierre Geuens (1993-94) who held that the Steadicam produces a totally disembodied type of viewing.

Even when delimiting in such a way the field of empirical investigation, as we did with our experiments, a caveat is in order: one should bear in mind that a lab is not a movie theatre and participants in the experiment are not members of a film audience (film scholars are obviously perfectly aware of this aspect, as it is at the basis of several experiments in the field of the neuroscience of film). The whole experimental context aims at mimicking those conditions in the best possible way, but it remains true that experimental conditions are nothing but an oversimplified and coarse replica of real life situations. Of course, this does not apply just to our experimental approach to cinema, but to cognitive neuroscience at large.

Any empirical approach uses experiments to verify hypotheses that generate predictions. Obviously, both hypotheses and predictions do not grow out from the void, but are consonant to and inspired by the presupposed theoretical background, hopefully based on previous empirical evidence.

We think that our hypotheses are based on rock-solid ground, as they capitalize upon almost three decades of neuroscientific research on the perceptual and cognitive role of the motor system, with results that go from single neurons’ recordings in macaques, birds, rodents and humans to non-invasive behavioral, EEG, and fMRI studies carried out on the human brain in hundreds of labs around the world. We believe that the adoption of a comparative perspective, framing the cognitive functions and aesthetic proclivities of humans within a broader evolutionary scenario may secure a deeper understanding of human cognition – hence also of film perception – than the experimental approach still endorsed by many cognitive neuroscientists, whose study of the brain translates in the neo-phrenologic reification of the ‘boxology’ of classic cognitive science into brain areas, supposedly housing the very same boxes. A telling example comes from the endless brain imaging experiments realized to support the hypothesis that propositional attitudes (e.g., beliefs, desires and intentions) ‘reside’ in distinct brain areas. Unfortunately, empirical evidence showed that the activation of those brain areas is neither causally relevant nor specific to engage in mindreading activity, whatever that means.

We think that these experiments that still receive the acritical acceptance by many quarters of cognitive science, are less illuminating on the relationship between brain and cognition than the perspective offered by the embodied cognition approach. With our book, we aimed to show the heuristic potentialities of this approach when applied to film theory.

When the debate starts, it means that it is time to make a new and updated point on the forms of confrontation between science and the arts, what we try to do, coming from a different training, working around the multiannual project of The Empathic Screen, and keeping open the discussion with colleagues, friends, and scholars from several fields of research. Are we exerting an optimism both of intellect and will? We don’t know, we are just doing research in a very challenging and promising field.

Response from Malcolm Turvey

I thank Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra for their reply to my blog entry about their book, The Empathic Screen, and its arguments about camera movement. Although they do not respond to my criticisms of their work, in their reply they reiterate some of the principles informing their neuroscientific research on cinema as well as the results of their experiments. Here, I will comment on some of these, pointing to areas of both agreement and disagreement.