Archive for the 'Poetics of cinema' Category

Poetics in motion, and sound

What is the sound of two hands flapping? (33:25).

DB here:

Ari Ernesto Purnama is a Ph.D. student in film studies at the University of Groningen. He has been attending the Belgian summer film schools I mentioned in the previous entry, and back in July he asked to interview me. He has kindly edited and posted the result on vimeo here.

The talk is about poetics of cinema as a research program, but I try not to get 100% hard-core academic. We discuss things like the long take, historical research into film style, and how the poetics perspective might be of interest to practicing filmmakers. Thanks to Ari and his DP Naki Naser Dauti for conducting this conversation.

A better picture of me, in my prime, is below.

James Alexander and DB, May 1948. Thanks to Darlene Bordwell for the photograph, taken by Marjorie Bordwell.

Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table

DB here:

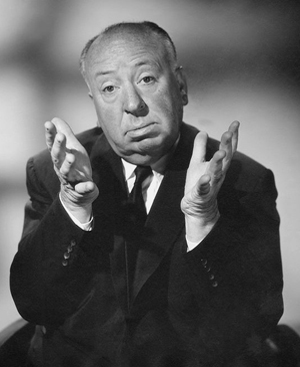

Every good cinephile knows Alfred Hitchcock’s famous distinction between suspense and surprise. In articles and interviews from the 1930s on, he explained that situations are more gripping if the audience has more knowledge than the characters do. His classic example, in conversation with Truffaut, was a bomb under a table.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but priot to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock, and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.

In Film Art, we invoke Hitchcock’s example to illuminate how narration can be more or less restricted. You can confine the narration to what only a character knows, or you can expand it to give the viewer story information that a character doesn’t have. By widening the audience’s knowledge somewhat, you can build suspense; by confining it, you can make the audience share the character’s surprise.

After Hitchcock came to the United States, he often invoked this distinction in interviews, and it became part of craft lore among writers of screenplays and genre fiction. I trace the idea’s fortunes a little in the online essay, “Murder Culture.” In practice, though, Hitchcock didn’t always follow through. Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) confine our knowledge very closely to the protagonist’s, without providing that wider perspective he advocates in his remarks to Truffaut. And surprise is central to some Hitchcock works, notably Psycho.

In other films, of course, he did follow his own advice. When Johnny Jones detours to the Tower of London in Foreign Correspondent, we know that the little man steering him there intends to kill him. Shadow of a Doubt lets us see Uncle Charlie in a sinister light before he visits Santa Rosa, and glimpses of his behavior strongly hint that he will menace Young Charlie when she starts to investigate him. And of course The Greatest Film Ever Made (or is it?) tips us off to what’s really going on with Madeleine/ Judy before poor Scottie grasps it.

I’ve wondered: Is this suspense/surprise distinction original with Hitchcock? In the tapes of the original interview with Truffaut, he notes: “You know, there has always been this dispute between suspense and surprise. . . . What I’m saying is not new, I’ve said this many times before.” He then launches into a more expansive account of the bomb-table scenario.

His formulation is ambiguous. Is the distinction “not new” because it’s been around a long while (“always”), or because he’s reiterated it many times? And is his preference for suspense an uncommon opinion? Exact answers may lie in the vast Hitchcock literature, but so far I haven’t found them. Here’s what I came up with.

What enduring disquietude

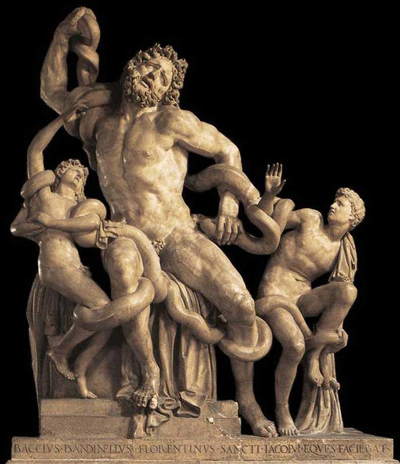

Gotthold Ephriam Lessing was a playwright and drama theorist. His Miss Sarah Sampson (1755) is sometimes considered the first “bourgeois tragedy” in German, and his best-known play is perhaps Nathan the Wise (1779), a classic that was made into a notable silent film. Lessing is also famous for his influential book-length essay Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766), which has been a center of debate in aesthetics ever since.

In that piece he argued for a fundamental distinction between time-based arts (drama, literature) and arts of space (painting, sculpture). From that distinction Lessing inferred a principle of decorum, or expressive fitness, for different media. He claimed that the famous sculpture showing Laocoön and his sons caught in the serpent’s coils could express only a split-second of pain, not the extended agony of their struggle. As a three-dimensional image, the father’s scream is vivid, but it lacks “all the intermediate stages of emotion” that a poem could have rendered as it unfolded in time. The great film theorist Rudolf Arnheim argued that the sound film obliges us to ask whether moving images and recorded dialogue cover different expressive territories, so he called his essay “The New Laocoön.”

Lessing also ruminated on the drama, and his thoughts about playwriting, set down in notes written between 1767 and 1769, contain many intriguing observations. In one passage, he replies to writers who have criticized ancient Greek playwrights for giving away too much in their prologues. These critics have implied that audiences would be more satisfied if big events took them by surprise. So, says Lessing mockingly, let’s simply reedit the plays and chop out all the information that sets up the final reversals.

His serious point is that a surprise yields only a transitory thrill. In the passage below, he uses “poet” and “poem” in a general sense, including storytellers and dramatists, plays and prose fiction.

For one instance where it is useful to conceal from the spectator an important event until it has taken place there are ten and more where interest demands the very contrary. By means of secrecy a poet effects a short surprise, but in what enduring disquietude could he have maintained us if he had made no secret about it! Whoever is struck down in a moment, I can only pity for a moment. But how if I expect the blow, how if I see the storm brewing and threatening for some time about my head or his?. . .

[By not preparing the spectator] the whole poem becomes a collection of little artistic tricks by means of which we effect nothing more than a short surprise. If on the contrary everything that concerns the personages is known, I see in this knowledge the source of the most violent emotions.

Lessing is evidently thinking of classic cases of recognition, plot twists that reveal connections among characters that they were long unaware of. (Oedipus is actually the son of the man he killed!) At another point, Lessing’s English translators find the word Hitchcock uses: “Our participation will be all the more lively and strong the longer and more confidently we have foreseen the issue.” “Foreseeing” here might be too strong, because in Hitchcock’s parable of the bomb we don’t really know the outcome. Will the men at the table escape in time, or halt the bomb, or be blown up? The inevitability of catastrophe that we expect in Greek tragedy produces a different sort of suspense than we experience in modern narratives. Yet it remains suspense nonetheless.

Lessing goes on to suggest that Aristotle valued Euripides most among dramatists not because of the plays’ gruesome endings but at least partly because “the author let the spectators foresee all the misfortunes that were to befall his personages, in order to gain their sympathy.” In other words, we have that sort of unrestricted narration we usually call omniscience. That’s what is at stake in Hitchcock’s bomb example.

Clairvoyant aloofness

It’s a long stretch from the late eighteenth century to Hitchcock’s time. Thanks to Google, and especially its wondrous Ngram software, we can get a rough sense of what happened to the duality of suspense and surprise in those intervening years.

A quick sampling shows that they were conjoined by the late nineteenth century. An anonymous 1884 critic finds that in Tennyson’s plays “the elements of suspense, of surprise, are altogether wanting.” In 1882, J. Brander Matthews, towering authority on theatre history, praises Hugo’s vibrant play Cromwell:

There is the familiar use of moments of surprise and suspense, and of stage-effects appealing to the eye and the ear. In the first act Richard Cromwell drops into the midst of the conspirators against his father,–surprise; he accuses them of treachery in drinking without him,–suspense; suddenly a trumpet sounds, and a crier orders open the doors of the tavern where all are sitting,–suspense again; when the doors are flung wide, we see the populace and a company of soldiers, and the criers on horseback, who reads a proclamation of a general fast, and commands the closing of all taverns,–surprise again. A somewhat similar scene of succeeding suspense and surprise is to be found in the fourth act.

Throughout this period writers fairly often counterpoised suspense and surprise as two essential strategies of plotting. But do the writers recognize the narrational implications they harbor, and do writers display Hitchcock’s preference for suspense? Yes to both.

George Pierce Baker, early twentieth-century drama macher, weighed in with his book Dramatic Technique (1919). He notes that in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I, a revelation of the Countess’s plan yields “a momentary sensation, surprise.” Baker reimagines two versions of the situation: When we know more than one of the antagonists does, and when we know more than both of them do.

Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of the Countess, and they had seemed very dangerous for Talbot. Then, as she played with him, there would have been more suspense than in Shakespeare’s text, because an audience would have been wondering, not merely “What is the blow Talbot will strike?” but “Can any blow he will strike overcome the seemingly effective plans of the Countess?” Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of both. Then, as we watched the Countess playing her scheme off against the plan of Talbot, of which she would be unaware, might there not easily be even more suspense? At every turn of their dialogue we should be wondering: “Why does not Talbot strike now? Can he save the situation, if he delays? With all this against him, can he save it in any case?”

Baker concludes that surprise enlivens the situation, but suspense allows for deeper characterization: awaiting an outcome, we must speculate on the characters’ temperaments, motives, and strategies.

Baker has already cited the Lessing passage I’ve mentioned, and he goes on to quote another authority of his period, William Archer. Archer’s Play-Making (1912) became something of a Bible for aspiring playwrights. (Preston Sturges swore by it.) Without explicitly mentioning suspense or surprise, Archer celebrates the pleasures of lording it over the characters.

The essential and abiding pleasure of the theatre lies in foreknowledge. In relation to the characters of the drama, the audience are as gods looking before and after. Sitting in the theatre, we taste, for a moment, the glory of omniscience. With vision unsealed, we watch the gropings of purblind mortals after happiness and smile at their stumblings, their blunders, their futile quests, their misplaced exultations, their groundless panics. To keep a secret from us is to reduce us to their level, and deprive us of our clairvoyant aloofness.

All of these drama theorists are promoting the well-made play as the best model for plot construction. They’re reacting against popular melodrama, with its episodic construction, wild coincidences, and startling twists–a model of what our colleague Lea Jacobs calls “situational” dramaturgy. The preference for suspense is a recognition of the playwright’s adroit shaping of the plot, preparing the later revelations carefully but also creating a steady arc of tension rather than a firecracker string of surprises. Suspense, it’s implied, is just more difficult to achieve than surprise, and a successful passage of suspense testifies to the writer’s skill.

In sum, by the time Hitchcock started his film career, the suspense/surprise couplet was fairly common in discussions of playwriting, and the superiority of suspense was more or less assumed. A 1922 essay concedes, “Whether or not surprise has a legitimate place in the drama is debated by commentators.” But the author, one Delmar Edmundson, suggests that an “entirely unexpected” turn of events in a one-act play can yield a valid thrill, just as in an O. Henry story. Still, the author suggests that even such a twist needs to be subtly prepared for.

In 1922 as well, Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship devotes a whole chapter, “Suspense, Excitement, and Crisis,” to the need to make the viewer “participate” in the action. The melodrama Lady X, then recently adapted to film, affords an example. The attorney defending an older woman is in fact her son, though neither of them knows it. (Shades of ancient Greek theatre.) The result is double suspense: we, like the characters, worry about the outcome of the trial, but we also wonder whether they will discover their kinship. “Had the woman’s identity been kept from the spectators till the end and then ‘sprung’ with explosive suddenness, fully half the emotional effect would have been stripped from the play.” Lessing had already anticipated the power of situations of unknown identity: “None of the personages need know each other if only the spectator knows them all.”

At this point, I can’t say precisely how Hitchcock learned of the distinction between suspense and surprise. Clearly, though, the idea was circulating in the theatrical and cinematic milieu of his early career. It’s entirely possible that he read Archer, Dimick, or some comparable source.

In any event, the distinction isn’t original with him. He is, however, the person who made it central to conversations about filmic construction. Recall that he always denied making detective stories. As the Master of Suspense, he wanted to play down the startling solution to a mystery and instead emphasize slowly building tension. And his continuing reliance on the distinction reminds us that the man always in search of what he thought was “purely cinematic” owed a great deal to the theatre. Some critics complained about divulging Judy/ Madeleine’s secret partway through Vertigo, but here, as in most of his films, Hitchcock was adhering to lessons learned from the well-made play. The result was a “disquietude” that endures.

Hitchcock’s remarks appear in Truffaut, Hitchcock, p. 52 of my 1967 edition. There he somewhat qualifies his position about superior knowledge, adding at the end of the passage I’ve quoted: “The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is itself the highlight of the story.” I take it that this plot construction is different from that of a mystery plot, which poses questions explicitly (whodunit?). A twist ending, by contrast, catches us by surprise because we didn’t suspect that certain aspects of the situation were in question. Central examples would be Stage Fright, Psycho, and, more recently, The Sixth Sense.

Truffaut’s Hitchcock book (the first hardcover film book I ever owned, I think) is a considerable condensation of the extensive interview. The sessions, punctuated by sounds of cigars being lit and snacks being eaten, are preserved on tape. Thanks to the Internets, they are available here. Hitchcock’s slightly more elaborate version of the bomb scenario occurs in session 4, starting at 17:44.

You can read the books I’ve cited in free digital versions: Lessing’s Laocoon and his essays on theatre; J. Brander Matthews’ French Dramatists of the 19th Century; William Archer’s Play-Making; George Pierce Baker’s Dramatic Technique; and Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship. Print editions are also available, of course. Other passages I’ve quoted come from Anon., “New Editions of Tennyson,” The Critic and Good Literature (15 March 1884), 123; and Delmar J. Edmundson, “Writing the One-Act Play VIII: Suspense and Preparation,” The Drama 12, 7 (April 1922), 258. Arnheim’s essay “The New Laocoön” is in Film as Art. For more on situational dramaturgy, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema (Oxford, 1998).

Thanks to Hitchcock adept Sidney Gottlieb for helpful advice on this entry. Anyone interested in Hitchcock needs to consult Sid’s excellent collections Hitchcock on Hitchcock and Alfred Hitchcock Interviews. The suspense/surprise duality recurs throughout them in varied forms.

Google’s Ngram software is here. It’s a tremendously useful tool for historical research.

I’d be grateful to anyone who can help pin down sources for Hitchcock’s acquaintance with the suspense/surprise couplet. As ever, feel free to correspond and I’ll update the entry as necessary.

P.S. 30 November 2013: Correspondence incoming! Richard Allen, NYU professor, lead guitarist, and Hitchcock expert, suggests in an email: “One suspects that the person who probably introduced Hitchcock to this was Eliot Stannard.” Stannard participated in writing all but one of Hitchcock’s all-silent films, and he published a short manual on screenplay technique, Writing Screen Plays (1920), derived from columns he published in Kine Weekly.

I haven’t been able to determine whether Stannard opined on the suspense/surprise duality, as the manual is extraordinarily rare, and the writing on Stannard that I’ve seen doesn’t explore this aspect of his work. Nonetheless I can recommend Charles Barr, English Hitchcock (Cameron & Hollis, 1999), 22-26; Barr’s article, “Writing Screen Plays: Stannard and Hitchcock,” in Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896-1930 (Exeter University Press, 2002), ed. Andrew Higson, 227-241; and especially Ian W. Macdonald’s chapter, “Hitchcock’s Forgotten Screenwriter: Eliot Stannard,” in his brand-new and enlightening Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 132-160. Further information on Stannard, or other sources of Hitchcock’s idea, remains welcome.

P.P.S. 2 December 2013: Ian Macdonald writes: “It’s very difficult, as you know, to trace the development of ideas such as the bomb in the briefcase/suspense-surprise thing. Stannard is surprising in that he clearly thought about how best to tell stories on screen, and came close to insights like Russian montage before those ideas became known in London (as Charles Barr has already pointed out). Unfortunately he did not continue to publish ideas after the early 20s, and his work is of course mixed up with ideas from everyone else in his ‘work group’. My picture of Stannard is built up from scraps, and his manual I have only seen in the British Library. This is tantalisingly aimed at the wannabe, so does not take ideas very far either. However, I’m sure he was aware of the prevailing doxa of play construction through such as William Archer, as others (like Brunel) were, and I’m sure that Hitch hoovered up Stannard’s ideas along with everyone else’s. As an inveterate theatre-goer, Hitch would also have been aware of ideas on suspense also. I will also have another look at my material specifically on this suspense question, for further clues, and let you know.” Thanks to Ian, Richard, and Sid Gottlieb for writing! More as things develop.

P.P.S. 5 December 2013: Oh, boy, have things developed. See the next entry.

P.P.P.S. 12 December 20113: Ashish Mehta has found evidence for the suspense-surprise duality in another eighteenth-century figure. He writes:

“Here’s what Samuel Johnson had to say in essay #3 of The Idler, published April 29, 1758, accessible here:

It has long been the complaint of those who frequent the theater, that all the dramatic art has been long exhausted, and that the vicissitudes of fortune, and accidents of life, have been shewn in every possible combination, till the first scene informs us of the last, and the play no sooner opens, than every auditor knows how it will conclude. When a conspiracy is formed in a tragedy, we guess by whom it will be detected ; when a letter is dropt in a comedy, we can tell by whom it will be found. Nothing is now left for the poet but character and sentiment, which are to make their way as they can, without the soft anxiety of suspense, or the enlivening agitation of surprise. (Emphasis added.)”

Thanks to Ashish for this!

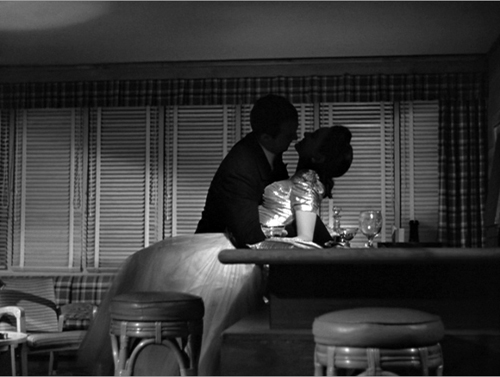

Vertigo (1958).

Otis Ferguson and the Way of the Camera

The original entry at this URL, published 20 November 2013, has been removed. Revised and expanded, it forms a chapter in the book The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture, to be published by the University of Chicago Press in spring 2016.

I discuss the development of the book in this entry.

You can find more information on the book here and here.

Thank you for your interest!

Twice-told tales: MILDRED PIERCE

Mildred Pierce (1945).

DB here:

At the climax of Now You See Me, a barrage of brief shots skips back in time to show how our quartet of magicians pulled off the complicated illusion we’ve just seen. (A very, very complicated illusion, in fact. You and I should be so lucky.) Soon our Four Horsemen come to realize that a puppetmaster behind the scenes has been steering them, and this awareness comes in another flurry of flashbacks.

Today’s movies are constantly using fragmentary flashbacks to fill in elements left out of earlier scenes. I recently considered how Safe Haven and Side Effects use the convention, but lots of other films will furnish examples. Crucial to this technique is an illusion created by cinematic narration. The first time through a scene, we think we’re seeing everything. But the replay shows us bits and pieces that were left out, or that we didn’t notice, or that we’ve forgotten about.

Back in 1992 I wrote an essay about this technique. “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce” focuses on the murder of Monte Beragon in the 1945 film. A revised version of the essay appears in Poetics of Cinema and is now available on this website. The piece tries to show that a cognitive approach to comprehension and recollection can explain how a film shapes viewers’ responses—in this case, creating mystery while making viewers forget certain things they’ve seen.

Today I’m going to consider Mildred again, but by doing something I couldn’t do in print. The wonders of the Internetz let me use video extracts to show concretely how clever this replay is. I frame my case here differently than in the earlier piece, although there are ideas and examples common to both. Perhaps what I do here will tease you into reading the more technical essay.

And of course there are spoilers—most thoroughly in reference to Mildred, more mildly in reference to Side Effects and The Unfaithful (1947).

Hiding murder

At the start of Mildred Pierce we see Monte shot down in a beach house, but we don’t see who did it. At the climax of the film, we’ll see a flashback replay the murder, filling in elements that were suppressed in the earlier version. In these sequences, director Michael Curtiz and the film’s screenwriters make choices about at least three narrative conventions.

How do you present the original scene? How do you handle the flashback? How do you present the replay?

These choices confront every screenwriter or director who wants the Aha! effect of dramatically revealing what was really happening in an earlier sequence.

The filmmakers’ decisions will be shaped by the urge to make the audience’s pickup fast and effortless. The filmmakers know that we tend to want to cut to the core of a story situation, to grab its gist and move on, and we trust that the film’s unfolding will help us do that. But this very speed can work against us. By counting on our knowledge of conventions, filmmmakers can encourage us to jump to conclusions that will turn out to be inaccurate.

Start with the handling of the original scene. Your choices are basically these: We can see the action fully, or we can see it only partially, with some aspects suppressed. Consider the opening of The Letter (1940). Leslie Crosbie strides out of a cottage, blasting away at a man who tries to crawl away from her.

We see the crime fully, so the mystery involves circumstances. What led up to this murder? The rest of the film’s plot will concentrate on that.

Alternatively, some element of the initial scene can be omitted. This is what we get in the shooting of Miles Archer near the start of The Maltese Falcon (1941).

It’s familiar territory. The film’s narration conceals the identity of the killer by framing him or her out of the shot. The question of who killed Archer will propel part of the action to come.

The crucial action can be suppressed even more thoroughly. In The Accused (1947), a woman is followed into her home. We already know her as a wealthy wife waiting for her husband to come home, but we aren’t shown the identity of the shadowy male figure who grabs her and forces his way into the house.

And the camera stays obstinately outside while someone is shot in the house.

Only later will we find out who the victim is, and the entire film will slowly reveal what really happened inside, and what led up to it.

I’ll have some things to say about Mildred’s initial murder scene shortly, but now let’s consider the second key convention: the flashback device itself. What is a flashback? Most basically, it involves presenting earlier story events in the midst of later ones. It’s often motivated as a memory, as when a woman recalls her childhood. But there doesn’t have to be a memory motivation; the film’s narration can directly show us bits of action that occurred in the past (as in the “objective” flashbacks in Kubrick’s The Killing).

Mildred Pierce is built on three flashbacks. Two long ones explain the course of her life with her family, and a final one dramatizes Mildred’s explanation of what happened during Monte’s murder.

What, then is a replay, the third convention I’m considering? I don’t think critics and filmmakers have a very stringent sense of this device. (See the codicil for further comments.) I’d suggest that basically a replay is a flashback that revisits scenes we’ve already seen. When our heroine recalls her childhood in scenes we didn’t see before, we have a flashback. But if later in the film we see those childhood scenes again, I’d call it a replay. Centrally, a replay revisits scenes we’ve already witnessed, or at least glimpsed.

So not all flashbacks are replays. Are all replays flashbacks? Some would say yes, but I’m more cautious. I’m inclined to say that a mechanical recording of a scene shown earlier could count as a replay without being a flashback. In Rebecca the newly-married couple watches home movies of their honeymoon. This scene fulfills the function of a flashback, but the action we see remains in the present: the couple are screening the film. The footage doesn’t show scenes we’ve already seen, but if it had, I’d call the screening of the movies a replay, but not a flashback—since, again, the action framing it is visible in the present.

This sort of mechanical recording/ replay is very common in modern films, reflecting the ubiquity of surveillance cameras, cellphones, and the like. In an earlier blog entry I talked about a purely auditory replay in Sudden Fear that’s made possible by an audio recording device. It would be odd to call the home movies or the SoundScriber playback flashbacks.

So some replays are flashbacks, and some aren’t. When they’re flashbacks, replays are often used subjectively, as when a character remembers an earlier action. Recall all those dream sequences that present, often with distorted imagery or sound, action we’ve seen previously in the film. But a replay may also supply new information about actions we already witnessed and thought we understood. We thought we grasped an earlier scene because nothing signaled to us that pieces of information were missing.

This possibility goes to another creative option. Sometimes the film tells us that something has been omitted. In my Maltese Falcon and Unfaithful examples, the narration is openly suppressive: It announces that it’s not telling us certain things. This of course adds mystery to the plot.

Alternatively, the presentation of the initial scene might be covertly suppressive; it hides things and doesn’t tell us it’s hiding them. In Side Effects, we see the heroine commit murder and then go to bed. Later the murder scene is replayed, but with extra shots showing actions we didn’t see or surmise before. The idea of replaying to fill in previously suppressed information is quite old; you can see it at work in Griffith’s Romance of Happy Valley and Ford’s Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. In modern cinema, we sometimes revisit an earlier scene several times, with each pass yielding new information (e.g., Go). You might want to call these “multiple-draft replays.”

Gunplay and replay

We start with two establishing views of the beach house, with a car outside. Over the second, gunshots are heard. Shot by an unknown assassin, Monte staggers forward and falls back onto the carpet. A close shot shows him saying, “Mildred” as he dies.

The camera tracks to the bullet-riddled mirror and we hear the sound of a a door. A new shot lingers on Monte’s corpse. We then see the car drive off.

The next scene shows Mildred pacing nervously on the pier.

I think that this opening lays out two options, one for the trusting viewer and one for a more skeptical one. The trusting viewer assumes that Mildred killed Monte. He seems to glance at her as he speaks her name, and the shot of the car pulling away leads smoothly to the sequence showing Mildred on the pier.

Not so fast, says the skeptical viewer. If Mildred did it, why doesn’t the film show her doing it, as the Letter scene does? The absence of a reverse shot of the killer resembles the missing reverse shot in the Maltese Falcon scene. So the scene leaves some doubt about whether Mildred is guilty.

The film rushes us along, so we aren’t obliged to decide one way or the other. Eventually we can reconcile the opening with either possibility. If Mildred turns out to be innocent, we can say the film played fair by not showing the killer. If she turns out to be guilty, the missing reverse shot will be seen as simply a device to postpone telling us.

She certainly acts guilty enough in what follows. On the pier, she seems to consider leaping into the surf, only to be put off by a cop on a beat. The lubricious Wally lures her into his tavern, where she stares coldly at him before suggesting they go to the beach house. There, she locks him in, and he discovers Monte’s corpse.

Passing policemen in a patrol car see Wally break out of the house and arrest him on the beach. Mildred’s daughter Veda is briefly introduced at their home, when two policemen come to take Mildred in for questioning. She seems to feign ignorance of Monte’s death, still trying to frame Wally.

At the headquarters, the police inspector announces that they have the killer—not Wally but Mildred’s first husband Bert. Distraught, she claims Bert is innocent and to exonerate him she tells her story, taking us through her two marriages and her successful career.

At the climax of Mildred’s second flashback, she realizes that Monte’s free-spending ways have enabled Wally to cheat her out of her restaurant chain. She fetches a pistol and drives to the beach house, in a framing that reminds the first-time viewer of the film’s opening shots.

We see her walk through the house, but then the flashback breaks off. We’re taken back to the present, with her talking to the chief detective. “Monte was alone, and I killed him.” The detective replies that she’s lying; someone else was in the house. Who? Not Bert but Veda, brought in by the cops who have grabbed her when she tried to leave town.

Before Mildred can hush her, Veda snaps out, “You promised not to tell! You promised! You said you’d help me get away!” Veda became increasingly important to the plot as the years went by in Mildred’s flashbacks, but her almost total absence from the opening minutes blocks our thinking of her as a candidate for the killer’s role. Soon we’ll see the pains the narration took to make sure we didn’t spot her at the crime scene.

Mildred breaks down and launches the final flashback.

She says that she found Veda with Monte, and they admitted to being lovers. Then Veda told her that she and Monte would be married. Mildred reached for the pistol but was halted by Monte and dropped the gun. She left, just before Monte told Veda he had no intention of marrying her. “You don’t really think I could be in love with a rotten little tramp like you, do you?”

The flashback crosscuts between Mildred in the car and what’s happening inside, bringing us back to the opening situation. Now the skeptical viewer’s hunch is borne out. The replay starts as a faithful version of what we originally saw, providing the reverse shot of Veda that was missing in the opening.

This time we don’t see Monte hit (that action is covered by the shot of Veda), but he crumples and staggers forward as before. He dies, still murmuring Mildred’s name. Mildred hurries in, finds her daughter standing over Monte’s body, and succumbs to Veda’s demand that she cover for her.

The replay explains why Mildred contemplated drowning herself afterward: She was in despair at the couple’s treachery and the crime that Veda committed. When suicide was blocked, Mildred tried to frame Wally for the murder in order to protect Veda. And the replay suggests that it’s not Mildred but Veda who drives off from beach house, leaving Mildred to drift down to the pier.

All together now

At least, that’s what most viewers would remember as happening. My essay argues that it’s just this broad effect that the movie aims for: we recall the gist of the murder situation, and we assume that the only gap in it is the identity of the killer. However, when we look more closely at the two sequences, we see that Curtiz and his colleagues have covertly concealed a lot more.

To get a sense of it, you can run the two sequences separately, then the two of them jigsawed together side by side. In the following clip, the opening is labeled scene A, the flashback replay is scene B. The shots in each passage are numbered. (In the original essay, they’re laid out in a chart.)

There’s a lot of sleight-of-hand here. The extreme long shot of the beach house and driveway (A-1) seems to set the stage. The car appears empty. By the time of the gunshots (first heard in A-2), though, based on what we know from the second flashback, Mildred must be in the car already. So you could argue that the dissolve to the long-shot of the car (A-2) conceals Mildred’s departure from the house and her efforts to start the ignition (B-1). I’ve wedged that later shot into the synthesized version to show the possibility. Otherwise we must assume that the initial shot of the whole landscape (A-1) follows her going into the car (B-1). Yet in that shot or the one that follows (A-2), we don’t hear or see the driver trying to turn over the engine. In either possibility, these opening shots display the sort of subterfuges that the film will execute more significantly soon.

The presentation of the action inside the beach house misleads us from the start. After Monte is shot, over the image of the bullet-pocked mirror (A-4), we hear a door, apparently closing. Because we don’t see anyone, and we assume that a murderer flees the scene of the crime, we infer that it’s the sound of someone hurrying out. In the replay, the door’s sound is linked to Mildred coming in (B-5), not leaving.

A little extra touch: When Mildred is shown entering (B-5) we hear the door make two sounds—opening and closing. Scene A, of course, doesn’t include both, so we quickly take the one door sound we hear as signaling the killer’s departure. (To my ears, Scene A includes the sound of closing; if that’s right, A’s narration has simply omitted the sound of the door opening.)

Moreover, the filmmakers have played with the duration of the first scene to an almost criminal extreme. After the shot of the mirror and the sound of “departure,” a straight cut takes us to a peaceful but ominous long shot of Monte’s corpse in the parlor (A-5). But this shot doesn’t reflect what happened right after the murder (B-5 through B-10). When the door opened and shut, Mildred came in and immediately started talking with Veda.

The shot of Monte’s corpse, if it has any place in the chronology of the scene, belongs later, evidently after Veda and Mildred have left the parlor but before Veda has driven off (A-6). In other words, version A has presented a big ellipsis—unmarked—between the mirror shot (A-4) and the shot of the dead Monte (A-5). All the drama between mother and daughter played out in the B version has been skipped over, without any hint that it was suppressed.

The sequence proceeds by degrees of sneakiness: First, the misleading presentation of the car and the beach house, then the teasing offscreen sound of the door, then the more forcible skipping-over of the conversation. Now consider something even more flagrant. When Monte says, “Mildred,” he says it in two different ways in the two sequences, and thus creates two different effects.

In the opening scene, an abrupt medium shot (A-4) stresses the line as the dying man’s last word. We know (especially after Citizen Kane) that last words are important, and Zachary Scott dwells on it, lolling his head from side to side glancing leftward, as if he were naming his offscreen killer. But in the replay, when Monte falls (B-4), he simply slumps to one side, head down, and mutters, “Mildred,” before flopping over on his back. Nor does Curtiz provide a closer shot. Now the line is tossed off, as if Monte were simply remembering his wife in his final moments.

In sum, the replay not only fills in missing information; it corrects the inferences we made during the first scene. Of course, the film’s narration had encouraged us—at moments, forced us—to make those inferences, all with the purpose of creating a false impression about who was in the house when Monte died.

You might object that these “rewritings” of the opening show less skill than we expect today. Films like Go (1999), One Night at McCool’s (2001), and Vantage Point (2008), let alone Now You See Me and Side Effects, strive to make the fragmented replays of an event dovetail neatly. But those films have been made in an era when people had the ability, on DVD, to rewatch films closely, and persnickety viewers can check for disparities. 1945 viewers couldn’t undertake the random-access probes into Mildred that we can. Moreover, as complex flashback storytelling became more widespread in the 1990s and 2000s, I suspect that there was a certain professional pride in making the sequence of events watertight.

More generally, Curtiz and company could be confident that very few members of their audience would recall the fine detail of a scene shown a hundred minutes earlier. I argue in the essay that as the film unrolls, the rapid pace of the action and our inability to stop and go back allows the filmmakers to juggle time, space, and the sequence of actions played out.

The filmmakers count on our inability to recall fine detail. How fine? If the replay had shown Monty falling face down rather than rolling on his back, I suspect that we would have noticed the disparity. But even trained critics, as I show in my essay, at the time and afterward, didn’t notice the smaller details that deviate from the initial scene, especially the point at which Monte says, “Mildred.” Curtiz and his screenwriters have worked comfortably in a zone of fuzzy recall.

The differences between the initial scene and the replay can’t be put down to clumsiness or accident. All the disparities in the opening nudge us to draw the wrong conclusions, whether we play the trusting viewer or the skeptical one. The omission of the reverse shot, the most obvious mark that Mildred might be innocent, is a convention, as we’ve seen; but the other tactics pursued by Curtiz and company are more innovative. The filmmakers have exploited our tendency to jump to conclusions and to ignore details, always in our search for the gist of the story.

In other words, filmic storytelling often takes advantage of mistakes we make in normal thinking. It even encourages us to make them.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson for preparing the extracts for this blog entry and to web tsarina Meg Hamel for posting the essay.

The misleading narration of Mildred Pierce has its parallel in crime fiction, particularly the thrillers of the 1940s. See this entry on the site for more background. A Ruth Rendell novel, Wolf to the Slaughter (1967), contains a boldly misleading opening that is somewhat similar to what happens in our film.

Some details in the presentation suggest that Curtiz has played fair. In A-6, the woman driving off seems to have a light-colored coat, not Mildred’s heavy fur one. A viewer seeing Mildred on the pier might doubt that she took the car. Still, I don’t think everything here is perfect. Close examination of a 35mm print seems to reveal a figure in the passenger seat of the car ducking down in A-2. And does Monte, falling to the floor in A-3, move his lips slightly? Did the scene as shot have him speak the line “Mildred” at that point, as he said it in the flashback? If so, did someone decide later on the insert (A-4) that underscores his last word?

For more on the planning of this scene and the overall production of the film, see the screenplay Mildred Pierce, ed. Albert J. LaValley (University of Wisconsin Press, 1980). You can sample some of LaValley’s enlightening introduction here. The opening scene of the screenplay is quite different from that of the film, but it does retain the false clue of Monte seeming to name Mildred in his death throes.

The narrational maneuvers on display here have counterparts throughout the 1940s, which is one reason I’m interested in that era. For more examples, see this synoptic entry. The critic Parker Tyler has some provocative observations on the film in Magic and Myth of the Movies (Secker & Warburg, orig. 1947), 193-205. His comments suggest how difficult it was for audiences of the time to recall exactly what had been shown: he speaks of “the sequence of camera shots in which we see the outside of the house, the woman’s figure (or was it two figures, separately?) leaving it, her ride in the auto, her walk on the bridge, her impulse to leap over…” (195). This is a good example of the constructive tendency of memory: We fill in and seem to remember things that didn’t happen.

A more theoretical point: Some people might say that it’s unhelpful to use the term “replay” to cover both one type of flashback and the mechanical capture of earlier action. Maybe we want to call these mechanical recordings “rerun” or “playback” scenes and reserve the term “replay” just for flashbacks, the dramatized renditions of the scene’s images and/or sounds. Perhaps a close look at The Conversation would allow us to sort these concepts more exactly.

In addition, I’ve used the term “replay” to refer to those do-over plots that we find in fantasy and science-fiction films like Groundhog Day, Déjà vu, and Source Code. Yet you could argue that given the parallel-universe premise of these films, each event is shown in its singularity, in a distinct time frame. The scenes we see aren’t revisitings of a single event, but rather different events. They merely seem like replays because they repeat certain features of events that have occurred in other dimensions. I guess we need some new terms!”Reset” or “reboot” plots?

Speaking of terms, narrative theorists will recognize in Mildred’s replayed flashback what Gérard Genette calls a paralipsis. Here the narration “sidesteps” an element during the initial presentation and later revisits the situation and fills in the information. See his Narrative Discourse (Cornell University Press, 1983), 51-52.

A last musing: Might viewers exposed to publicity come into the film expecting Mildred to be the culprit? (On Mildred‘s marketing, see Mary Beth Haralovich, “Selling Mildred Pierce: A Case Study in Movie Promotion,” in Thomas Schatz, Boom and Bust: American Cinema in the 1940s (Scribners, 1997), 196-202.) The French poster below seems to put her in a doorway with a smoking gun. Or is that Veda in the doorway? Perhaps the uncertainty of the narration is prefigured by this advertisement.