Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Roger Ebert

Roger Ebert at 4 Star Video Heaven, Madison, Wisconsin, 2003.

Kristin and David:

Roger died today. We can’t do him justice in such short compass, but we do want to acknowledge him and his life. He was an unstinting friend to us, and a great and good force in American film culture.

The Sun-Times obituary is here.

Later 4 April: Jim Emerson’s personal tribute is here.

5 April: Chaz Ebert’s statement is here.

6 April: Jim Emerson has gathered a constantly expanding collection of tributes here.

7 April: Rodney Powell of the University of Chicago Press offers recollections here.

Roger and Chaz Ebert, Ebertfest, Urbana, Illinois, 2010.

Donald Richie

Donald Richie and students. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

DB here:

He died last week, aged 88.

What was his life about? The public dimensions involved, of course, his status as unofficial spokesman, principal gaijin, the gatekeeper and guide to anyone interested in Japan. He hosted grad students as genially as he played tour guide to Truman Capote and Susan Sontag and Jim Jarmusch. I don’t know of any other situation in which an American (from Lima, Ohio, no less) became the spokesperson for a foreign culture. From the 1950s into the 2010s, in a stream of writings and lectures, he interpreted how the Japanese lived, worked, thought, and created. Although he wrote about everything from landscape to tattoos, he became best known as the supreme expert on Japanese cinema. His particular love was the postwar “Golden Age” of the late 1940s through the early 1960s.

Tokyo/Hibiya crossing; Dai-Ichi Building, 1947.

Japan was still terra incognita to Westerners when he came there in 1947. When the outer world demanded to understand this very strange place that had fought so tenaciously against America, there arose a generation of interpreters. Of that cadre, though, he stands out as the man you can’t quite place.

The oldest of the group was Edwin Reischauer, who worked largely in international policy. A somewhat younger man, Donald Keene, became the dean of Japanese literary studies. Keene has provided translations and magisterial overviews of the Japanese novel, drama, and poetry. An almost exact contemporary of Keene’s is Edward Seidensticker, who has been a renowned translator and cultural historian.

Only a little younger was our author, who came to Japan in the Navy and soon became a prolific writer. Yet his work didn’t fit the mold of the other American experts on Japan. He was neither a traditional scholar (he read little Japanese, though he spoke it fluently) nor a pure journalist (he refused to be tied to topicality). He remained resolutely in-between. What academic would have the brass to sum up “The Japanese Way of Seeing” in a seven-page essay? Yet what journalist would write subtle critical monographs on Ozu and Kurosawa?

In my copy of Partial Views: Essays on Contemporary Japan, he wrote: “For David, from Donald, particularly pp. 157-205.” On those pages you find his “Notes for a Study on Shohei Imamura.” It’s a fertile survey of recurring themes and techniques in Imamura’s films. In the hands of a professor it could certainly become a tightly argued book. Was his inscription telling me that, when he wanted to, he could execute criticism with an academic accent? If so, it was unnecessary. I didn’t need convincing. I think he could have done whatever he wanted.

What he wanted, I think, was to join the tradition of European belles lettres. He earned his living by writing, and doubtless his championship typing skills steered him toward the quick turnover of daily deadlines. More deeply, I think, he found the shorter piece suited his flair for precise evocation. Even in his books, his approach is essayistic, faceted. His tone—thoughtful but not severe, conversational, projecting wide knowledge and good sense and humane modesty—won the reader by its quiet conviction that the subject was important. This essay wouldn’t be the last word; indeed, he would likely return to the subject years later, testing out new ideas. Much of his output consists of occasion-based pieces, and any of these might be recast, cut, or expanded. A craftsman knows how to recycle scraps and spruce up old projects.

This commitment to fluent reflection on daily changes, along with a quality of seeing everything around him afresh, put him in the tradition of the Continental “man of letters.” He was an aesthete, a moralist, and a bit of a dandy. His natty clothes were like his literary style, crisp and elegant but not flamboyant.

His preferred mode was description. He was convinced that whereas Westerners struggle to probe the depths, “The Japanese realize that the only reality is surface reality.” During a visit to Madison, he was delighted to find a translation of the Goncourt brothers’ journals. I couldn’t help thinking that he took them as a model of the urbane curiosity and pellucid prose he cultivated.

Above all he was interested in people. He was an excellent observer but also a well-tempered listener. He chatted with barbers, students, masseuses, neighbor ladies, potters, delivery boys, executives, and celebrities. He listened to their complaints, their dreams, and their reports on the texture of their lives. Sometimes they quarreled with him or disappointed him. But each one gave him a glimpse of the wavering mirage that was Japan, or at least his Japan.

Ikiru (Kurosawa, 1952).

His writing skills worked on a big canvas in The Japanese Film: Art and Industry (1959). He wrote the text while his collaborator Joseph Anderson, who read Japanese, provided the research. The book came at just the right moment, when Americans were starting to appreciate the power of this nation’s cinema. To this day, despite many specialized studies of directors, periods, and genres, it remains the standard overview of one of the great national film traditions.

Just as important, for me at least, was The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968). The first edition, a magnificent buff volume with razor-sharp illustrations and double-column text, is a triumph of book design, as solid and imposing as the films it canvasses. Along with Robin Wood’s works on Hitchcock and Hawks, it showed that cinema could be studied with intellectual seriousness. To the auteurist’s search for the guiding themes of a director’s vision, the Kurosawa book brought a sharp eye for technique and a direct access to the artist himself. (Our author’s first visit to a movie set was to Drunken Angel.) And it proved that a great film could sustain shot-by-shot scrutiny.

Turn to any chapter and you will see a probing intelligence. For Ikiru, we get a detailed layout of image/ sound relations in the nighttown sequence, bracketed by Watanabe’s funeral. The analysis carries us to this conclusion:

He has become much more than simply dead. Just as, dying, he learns to live; so, dead, he becomes more alive for others than he ever was before.

The Kurosawa book remains an exceptional achievement in sympathetic imagination. The critic is so finely in tune with the creator’s sensibility that each chapter illuminates and amplifies the dynamics of the film. There are other ways of understanding Kurosawa, but this book will remain the compass that orients us to this essential director’s career.

Floating Weeds (Ozu, 1959).

There were other books, of course. Among the best is the rare 1961 Japanese Movies, published by the Japan Travel Bureau. It is a compact survey of the major directors working in the postwar era. You sense that its intense aesthetic appreciation of particular films arises from portions cut from The Japanese Film. Here the critic is working at full stretch, and his thoughts on Naruse, Mizoguchi, and others are still worth reading. In its fifteen pages on Ozu, then unknown in the West, lie the seeds of his book on the director.

We have him to thank for our awareness of Ozu. He persuaded the reluctant Shochiku company to release the films in Europe and the US. His ten years of effort were crowned by the release of several Ozu films in New York in 1971-1972. At that point, largely as a result of accidental access, Tokyo Story emerged as the director’s official masterpiece. Soon afterward there appeared Ozu: His Life and Films (1974), another monograph informed by personal acquaintance with the director.

The Kurosawa book dealt in depth with each film, but this took a more horizontal and modular approach, tracing a skein of similarities across Ozu’s work. As one would expect, the emphasis falls on the postwar films, which were more easily available and which the author saw as they were released. (“Revisionist” takes on Ozu, and Japanese cinema as a whole, would soon return to the 1920s and 1930s and find there an earlier Golden Age.) The chapter layout tends to assume that Ozu films are more uniform than they are, but for its attention to themes and script construction in particular Ozu is indispensable. The author’s love for the films shines through every page.

It’s sometimes said that he brought Japanese cinema to the west, but apart from his championing of Ozu, this is inexact. Rashomon opened in New York in 1951, and Gate of Hell won an Academy Award in 1955. Daiei and Toho studios exported several films to Europe and America, while distributor Thomas Brandon sought to bring less-known Kurosawas to the US. The Japanese Film arrived at a propitious moment in 1959, when it could capitalize on the wider circulation of titles. Not until the 1970s was America to see a resurgence of interest in Japanese cinema, thanks to the Ozu releases, the Ozu book,the circulating programs sponsored by the Japan Film Library Council, and the efforts of Daniel Talbot’s New Yorker Films.

Still, our author did something quite important. By talking about Japanese cinema in terms amenable to Western tastes, he integrated it into our film culture. Kurosawa as a robust humanist; Ozu as the serene contemplator of life’s transience: these became familiar figures thanks to his eloquent critical rhetoric. At the same time he retained a sense of their uniqueness, insisting in particular on the irreducible Japaneseness of Ozu’s aesthetic.

Although his major books remained essential for film lovers and film courses, it’s fair to say that he got a second wind in recent decades. He won a wide and keen following with his commentaries and liner essays for Criterion DVD releases of Japanese classics. The outpouring of grief after his death comes in large part from viewers who knew him best as a warm, calm voice talking through scenes of Tokyo Story or When a Woman Ascends the Stair or, surprisingly, Bresson’s Au hasard Balthasar. He adjusted well to the new world of video. He treated it as a new conduit for his commitment to civilized discussion.

Five Filosophical Fables (Richie, 1967).

So much for the public man, writer and speaker and animator of film culture. Another side of him was an intense erotic interest. On your first meeting, he made sure you knew what he found appealing. In the Journals, cruising and pickups blend with a swarm of local details of landscape and custom, although consummations are elided.

I had noticed that his suteteko, being thick cotton, are still damp from the swim, and so I suggest he take them off and hang them on a branch to dry. He does so.

*

Later, in the afternoon, I take a train around the coast. . . .

The juxtapositions between moments of artistic ecstasy and sexual passions give the journals a collage-like snap.

[Hiteki] got into all this ten years or so ago. Has no particular feeling for it but it is now all he knows. . . . Does everything but only, I feel because he does not know what else to do. It apparently means little. Small excitement. . . It represents, I guess, something better than nothing.

6 October 1990. Haydn quartets—the delicious Opus 50. They are made up only of themselves.

The diaries we have are very polished products, the results of much rewriting, and stretches are calculated to render the guilt-free sexiness that the wanderer finds all around him. Consider the finesse of this passage about a visit to Aoshima island:

Later we shop in the empty tourist arcades and buy some beautiful and indecent objects—cups you turn over to discover a coupled couple, an articulated vagina disguised as a shell, and a sake cup with a mushroom-shaped penis attached. One is to suck the sake from the mushroom head.

Some readers expect the Journals to be among the author’s most lasting work. They’re valuable as chronicles of the daily life he observed with sympathetic but dispassionate acuity, but they also record the mind and feelings of a man of Wildean sensitivity wandering among dazzling surfaces that kept his senses, and his libido, ever on the alert.

The surfaces might be rough. The journals record his enjoyment of living near Ueno Park, where the homeless and the prostitutes gather at night. He strolls through them, meeting the occasional cop and seeking, as he puts it, someone who can typify Japan in all its contradictions.

Beautiful and indecent: You can find this mixture in some of the experimental films he made too. The most inoffensive of these, Wargames (1962), was circulated among American film societies during the 1960s, but others are more audacious. In the allegorical satire Five Filosophical Fables (1967) a young man abandons a snooty party, strips to the buff, and strolls smiling through Tokyo streets, past the sea, and into the countryside. Cybele (1968), a documentary of an avant-garde theatre performance, presents an orgiastic rite of sex, degradation, and bloody sacrifice.

Roppongi Hills, Christmas 2010.

He was assailed by bouts of illness across two decades, but he seems never to have lost his buoyancy and spiky wit. He was especially mordant on the New Japan. He notes that the thrusting high-rise apartments of the 1980s bubble offer more for Godzilla to whack. “Originally [he] had to content himself with a mere Diet building.” Manga and the Sony Walkman were very much alike, he maintained. Each offered not visual or aural stimulation but a convenient way to shut oneself off from the ugliness of a money-grubbing society: solitary withdrawal amounted to a critique of contemporary life. With mock pathos he told of a salaryman so preoccupied with talking on his cellphone that a passing subway train snagged him and carried him off, the handset dropped squawking to the platform.

The humor could be self-deprecating. One of our conversations:

DB: I liked The Inland Sea.

DR: I traveled for three months and wrote it in three weeks.

DB: And I read it in three hours.

DR: You took too long.

When asked if he loved Japan, he replied, “That’s complicated . . . I love Tokyo.” Yet by the end of his life, his city had become alien to him. His Japan Journals begin by sketching the vibrant colors of a blasted landscape returning to life.

Winter 1947. Tokyo lies deep under a bank of clouds which move slowly out to sea as the sun climbs higher. Between the moving clouds are sections of the city: the raw gray of whole burned blocks spotted with the yellow of new-cut wood and the shining tile of recent roofs, the reds and browns of sections unburned, the dusty green of barely damaged parks, and the shallow blue of ornamental lakes. In the middle is the palace, moated and rectangular, gray outlined with green, the city stretching to the horizons all around it.

The final entry in the journals is dated nearly sixty years later and records a 2004 trip to his old neighborhood. Tansumachi of 1947 had become the fashionable Roppongi Hills district, “the new Japan—gargantuan, expensive, and wasteful.” A Louise Bourgeois statue looms over the pavement like a tarantula. He recalls the street once named Dragon’s Way and the friend’s house that used to stand at that corner. He knows that his nostalgia must seem tiresome and he acknowledges that rapid change is itself a Japanese tradition, a sort of high-tech version of the Floating World. Yet he cannot resist denouncing the Disneyland that the old place has become. He finds no arresting color or light in this world.

In just a number of years every place will look like it, and this kind of economic expediency will be the rule, as will those cute nods in the direction of retro and trad, that comedy team of contemporary design. Here, under the spider, I look into the future which is already here.

He was well aware of living in-between. Today we might say that he was perpetually “other,” too aesthetically sensitive for a mercantile society, too protective of tradition in a period of lightning change, too gay for straitlaced America, too eccentric and independent-minded for assimilation into his adopted nation. Painful as these tensions must have been, he proudly accepted being fundamentally out of place. At the end of one essay he claims his motto to be that of Hugo of Saint Victor:

The man who finds his homeland sweet is still a tender beginner; he to whom every soil is as his native one is already strong; but he is perfect to whom the entire world is as a foreign land.

Extracts from Richie’s writings come from The Films of Akira Kurosawa (1968 and later editions), A Lateral View (1992), and The Japan Journals, ed. Leza Lowitz (2005). Richie’s films are available on DVD as A Donald Richie Film Anthology from Image Forum Video. See also The Donald Richie Reader (2001), ed. Arturo Silva, for a varied collection of pieces, including articles on how he came to write about film, and his lively tour Tokyo: A View of the City (1999), with photos by Joel Sackett. The photo of Tokyo/ Hibiya crossing comes from the Journals, the shot of Roppongi Hills from Tokyofashion.com.

For a provocative review of The Japan Journals, see Richard Lloyd Parry’s “Smilingly Excluded.” Kim Hendrickson, who produced Richie’s DVD commentaries, provides a tribute on the Criterion site. A list of his commentaries and liner notes is on this page.

For more on how Japanese films came into the United States, see Chapter 6 of Tino Balio, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973.

Thanks to Tony Rayns for conversations and assistance.

Elsewhere on this site are other Richie-related entries, particularly here and here.

P.S. 25 February: Karen Severns has set up a Donald Richie tribute page here.

Donald Richie at the grave of Ozu. Kitakamakura, July 1988. Photo by DB.

A hobbit is chubby, but is he off-balance?

Kristin here–

I first read J. R. R. Tolkien’s work during what might be described as the second generation’s discovery of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. The Hobbit was very popular from its initial publication in 1937, enough so that the publisher asked for a sequel. Though Tolkien wanted LOTR to come out in a single volume, postwar austerity dictated that it be divided into three separate volumes. After their publication in 1954-55, a devoted following grew. The real explosion, however, came in 1965, when the Ballantine paperback editions appeared in the USA.

I was fifteen at the time and already an aficionado of Victorian literature (H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne, Arthur Conan Doyle). I was used to reading long books (David Copperfield, Don Quixote). Like so many other people who were in high school or college in the 1960s, I loved Tolkien from the start. Eventually I became an academic writer. At some point, I decided to write a book on the two Hobbit novels.

I had done a lot of reading and note-taking for that project by the time of the release of Peter Jackson’s film version, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring. With reservations, I liked that film. What fascinated me more, though, was the incredible success of the innovative marketing and merchandising side of the LOTR franchise. I decided this film was going to be historically significant in a major way. In 2002, I decided to write a book about it.

The Tolkien study was put way back behind even the back burner. The franchise book needed to be written now, when I could (I hoped) get access to the filmmakers and to information that would not be available after the last part was released. With enormous good luck and help from many interviewees, I managed to write The Frodo Franchise (2007). My Tolkien project came forward onto the stove and is now in progress.

I’ve kept up my interest in the films, though. Editors have asked me to write short pieces on Jackson’s LOTR, and I’ve done four of those so far. I maintained my Frodo Franchise blog until it became apparent that I would not be granted access to the filmmakers for a book on The Hobbit. Now I’m on the staff of TheOneRing.net, for which I write occasionally. Naturally I’ve kept up on the progress of Jackson’s new trilogy.

Not long ago in these pages, I wrote about the fact that The Hobbit had been expanded from its originally announced two parts to a three-part film. To those who accused the filmmakers of doing this for strictly mercenary purposes, I countered that there were reasons why such an expansion could work well. Mainly these relate to the extra material in the appendices of The Lord of the Rings, which provide information on two kinds of events: those taking place during the time period when The Hobbit’s action unfolds (most importantly an attack on Sauron’s [aka the Necromancer] lesser dark tower Dol Guldur) and those which took place in the past but which relate to characters and actions in the novel (e.g., Smaug’s attack on Erebor and Dale, the Dwarves Pyrrhic victory over the troops of the Orc Azog at Moria).

Having now seen The Hobbit three times, I want to suggest how successfully, if at all, the filmmakers have incorporated this material. For the most part the non-Hobbit material has been brought in well, or in some cases acceptably.

It’s a prequel now

One objection to the division of The Hobbit into three parts is that the book won’t support a narrative nearly as long as that of the filmed LOTR. Over and over, fans and critics have complained that Peter Jackson’s adaptation of The Hobbit (1937) isn’t designed as Tolkien wrote it, as a children’s story, lighter in tone and shorter than LOTR. They often also object to those who refer to it as a “prequel.” The novel’s events took place years before those of LOTR. It was also published first, appearing in 1937, while LOTR came out in three volumes published in 1954-55. The implication is that Jackson should just have ignored the other film and stuck strictly to the novel, which is about a quarter the length of the LOTR tome. As literature, LOTR is a sequel to The Hobbit.

But the films are different. Even if The Hobbit were adapted page by page, speech by speech exactly as written, those of us who have seen the LOTR film or read the book could not see it as a separate tale. We know already what the Ring is and what eventually happened to it, while readers, if they started with The Hobbit, do not. We know that Elrond is a powerful leader among other powerful Elf leaders, destined eventually to leave Middle-earth for the Undying Lands. We know Gandalf is a wizard who will guide the various peoples through the War of the Ring. And so on. Only viewers who see The Hobbit without having seen LOTR first or having read the book or having read any of the extensive media coverage of both could come to the prequel unaware of such things. And while the novel The Hobbit is not a prequel, the film adaptation certainly is.

Because most of us do know about these major characters and premises, Jackson and his team could hardly avoid trying to make the new film match his version of LOTR. He had to treat events, characters, tone, and setting with some consistency, and he had to link the films as one long account of historical events in the same era of Middle-earth.

Tolkien himself tried to smooth out the disparities between The Hobbit and LOTR, both in tone and causal connections. He revised The Hobbit slightly in 1947, mainly to make the Riddles in the Dark scene work better in the light of what the Ring eventually became when he brought it back as a more crucial plot element in LOTR. In 1951, those revisions got into the second edition of The Hobbit and have remained canonical ever since. In 1960 Tolkien was again disturbed by the differences between the two books and launched into a more thoroughgoing revision of The Hobbit to make it conform exactly to the later events in LOTR. Others convinced him that this was a mistake and that it damaged the charm of the earlier book, already a classic of children’s literature. Eventually he allowed those disparities to remain. He did, however, write passages in the appendices that at least briefly described events that helped stitch the two books’ narratives together.

I don’t see that it’s a problem for the filmmakers to use those passages to try and make their films flow more smoothly from the first to the second. In a few years we will be able to watch all six parts of what will then essentially be a single narrative with a sixty-year gap in the middle. For better or worse, depending on one’s opinion, this is Jackson’s Hobbit. Unlike Tolkien, he is making it after already having made LOTR. He can include the links between the two tales, as well as extra plot material that Tolkien published in the 1950s but hadn’t conceived in the 1930s. The question is not whether those links and that material should have been included but whether they have been well handled.

In terms of the links, many of the ones in An Unexpected Journey seem effective. The notion of starting The Hobbit at a point just before Gandalf’s arrival for Bilbo’s 111th birthday party seems a good one: we see Frodo nailing up the “No Admittance” sign from the early LOTR scene and then heading off to read in the woods and await the wizard (above). There’s an immediate recognition factor. The younger Bilbo mentions Bree, a locale seen in LOTR, and he recalls Gandalf’s fireworks from his youth. A fireworks display also figures in Bilbo’s birthday party scene in LOTR. Bilbo’s initial awe upon arriving in Rivendell and his reluctance to leave it tie in with the fact that he goes to live there after leaving The Shire early in LOTR. Certainly the inclusion of Balin, made into a more prominent character than he is in the novel and played with considerable humor and charm by Ken Stott, should make the discovery of his tomb in LOTR a more meaningful and poignant scene. On the whole, the stitching together of the two films so far is quite accomplished, and I assume it will continue to be so through the other two parts.

But is it padded?

Most of these links between The Hobbit and LOTR are brief references or gestures, made in passing. They are not the reason that Jackson’s team decided, to considerable critical and fan uproar, to make The Hobbit in three parts rather than the originally announced two. In the earlier entry, I suggested that there was material in the appendices of LOTR that fills in information relevant to The Hobbit’s plot.

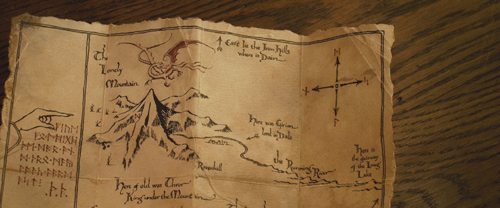

There’s the backstory of the Dwarves, involving two major events. Bilbo’s exposition at the beginning establishes their great kingdom within Erebor (the Lonely Mountain). Its king, Thror (Thorin Oakenshield’s grandfather), oversees the accumulation of a huge horde of gold and gems, and it attracts the dragon Smaug. Smaug’s destruction of the Dwarves’ home and the neighboring city of Men, Dale (portrayed briefly in a sort of Renaissance Italian style), leads to the Dwarves’ exile and hereditary king Thorin’s eventual decision to try and retake Erebor.

Second, there is the great battle fought between the Dwarves and Orcs at Moria, in which Thror is killed and Thorin earns the respect of his people by defeating the great Orc leader, Azog—chopping off his arm and leaving him, as Thorin wrongly assumes, to die.

All of this the film explains in flashbacks derived from the LOTR appendices, and this embedded material seems to me to come off well. In my opinion, most of the other scraps of text used as the inspiration for scenes not in the original Hobbit novel results in reasonably successful scenes—with one major exception, which I will deal with in the next section.

The most important extra plotline concerns the White Council (not so named in the first part of the film). Initially I speculated that the White Council scene would be a flashback to an early meeting. That’s not the case, since Gandalf meets with Elrond, Galadriel, and Saruman during the visit to Rivendell (above). In the novel, when Bilbo and Gandalf revisit Rivendell on their way back to The Shire, the Hobbit simply overhears Gandalf talking to Elrond: “It appeared that Gandalf had been to a great council of the white wizards, masters of lore and good magic; and that they had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood.”

Here, by the way, is an example of the sort of inconsistent plot points that Tolkien presumably hoped to eliminate when he struggled to revise The Hobbit in the early 1960s. By then he had written LOTR and given the Wizards their emblematic colors, so Saruman (and later Gandalf) was the only “White” wizard. The “Necromancer” would become Sauron; the “dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” gained a name, Dol Guldur. What Jackson and the other writers have done is to move that meeting of white wizards (which took place somewhere to the south, presumably either in Lothlórien and Orthanc) to Rivendell. That simplifies things.

Now the question remains, to what degree does the White Council hint that Saruman has already become treacherous? Is he dismissing Gandalf’s worries as exaggerated merely because he’s conservative and just doesn’t much respect the Grey Wizard, or is he secretly searching for the Ring himself (as Tolkien revealed in the appendices)? I hope these questions will be explored further in one or both of the upcoming parts.

Interestingly, Gandalf is already visibly frustrated by Saruman’s presence at Rivendell, and the two are at odds about the degree of danger evidenced at Dol Guldur. Saruman favors inaction, meaning that he opposes the Quest of Erebor. Gandalf sees all sorts of ramifications in the presence of the dragon and the odd goings-on at Dol Guldur. Obviously we know Gandalf is right, especially since Galadriel sides with him from the start. The explicit representation of this action within The Hobbit’s plot is, I think, off to an excellent start. I look forward to seeing how it develops.

Gandalf’s seems to regard Saruman with a mixture of frustration, annoyance, and forced friendliness and deference. How will this attitude affect our perception of Gandalf’s words about Saruman when he prepares to go and consult the White Wizard in The Fellowship of the Ring? There, as Frodo prepares to take the Ring and head to Bree, Gandalf says, “I must see the head of my order. He is both wise and powerful. Trust me, Frodo, he’ll know what to do.” In retrospect, Ian McKellen’s reading of these lines in Fellowship works in remarkably well with Gandalf’s attitude toward Saruman in the White Council scene in The Hobbit. He speaks the first two sentences quickly, without inflection, as if reciting them; we could interpret them as arising from a sense of duty rather than hope that Saruman really can or will help. The “Trust me, Frodo” sentence is accompanied by a tight smile, perhaps the sort of forced smile that Gandalf assumes as he turns to greet Saruman in the White Council scene. Given that neither director nor actor was presumably looking forward to someday adding such a scene, they turned out to be lucky that Gandalf’s speech was delivered in such a way that it could imply a lurking dislike or distrust of Saruman. (There is evidence for such distrust in the novel. In his long conversation with Frodo about the Ring, Gandalf remarks “I might perhaps have consulted Saruman the White, but something always held me back …. His knowledge is deep, but his pride has grown with it, and he takes ill any meddling.”)

One admirable thing about the Rivendell sequence is that the friendships among Elrond, Galadriel, and Gandalf are portrayed. In the book, these three have known each other for two thousand years. They are the bearers of the Three Elven Rings. Those who know only the film of LOTR are unlikely to be aware of that, since only in the penultimate scene at the Grey Havens are the three openly wearing their Rings—barely noticeable even on the big screen. Oddly, however, the licensed tie-in products for LOTR included replicas of Narya, Nenya, and Vilya, made by the Noble Collection. The three characters are able to communicate telepathically. Elrond, portrayed as rather aloof in LOTR, is a warmer figure here, embracing and teasing Gandalf, and the scene after the White Council meeting in which Galadriel reassures Gandalf and offers him her help is one of the most genuinely moving moments in the film (see top). (We never saw Galadriel and Gandalf together in the LOTR film, though they are together in some of the late book chapters that were cut in the adaptation.)

Radagast the Fool

Then there’s Radagast. The Brown Wizard appears in one scene in the novel version of LOTR, but Jackson and company eliminated him. Radagast is only mentioned in The Hobbit, but now he appears in two extended scenes and presumably will return in the later parts. Many fans object to Radagast’s being made into a comic figure, driving a sled pulled by large rabbits and hosting birds in his hair, with a resulting streak of droppings down the side of his head. Never mind that in Radagast’s one scene in LOTR, Tolkien portrays him as faintly comic, as well as timid and ineffectual. While pumping up the humorous side of the Brown Wizard, Jackson develops him into a character with considerably more gumption.

It has also been claimed that his role in the drama isn’t significant enough to warrant his presence. Did we really need all this time devoted to someone who’s there mainly to give Gandalf the Morgul blade as evidence of foul goings-on at the seemingly deserted Dol Guldur? Yet the dialogue does help motivate his importance. Gandalf declares to Bilbo, “He keeps a watchful eye over the vast forest lands to the east, and a good thing, too, for always evil will look to find a foothold in this world.” That dialogue hook leads to the first scene with Radagast, walking through the forest and finding death and decay, evidence of a mysterious force that he traces to Dol Guldur.

And the blade brought to Gandalf is definitely a significant object. When Gandalf presents it to the Council, Galadriel is very perturbed by it, and Elrond loses his initial certainty that Middle-earth is at peace. By the end of the scene, only Saruman denies the need to investigate what’s going on at Dol Guldur. Gandalf’s visit to Dol Guldur and the White Council’s subsequent actions in relation to the Necromancer’s presence there will form a crucial subplot in the upcoming parts; we’ve already glimpsed part of Gandalf’s exploration of the stronghold in the trailers.

Radagast also serves to draw the Orc band away from the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf. He drives his infamous bunny sled across the rolling hills, allowing the group time to find the hidden entry into Rivendell. But is the bunny sled so very ridiculous? Teanna Byerts, aka swordwhale, a member of the Message Boards at TheOneRing.net, has written an informative and amusing essay, “Radagast’s Racing Rhosgobel Rabbits: A Recreational Musher Looks at the Realities of Bunny Sledding.” It turns out that a sled would not be a bad vehicle for a woodland environment, and, allowing for the fact that this is a fantasy film, large rabbits not entirely implausible beasts for pulling them. (A Google Image search on “large rabbit” brings up some bunnies about the size of Radagast’s–and no, they’re not all Photoshopped.) The main problem is that ordinary rabbits would not pull as a team, but as Radagast says with relish, “These are Rhosgobel Rabbits!”

Although there is probably too much silliness relating to Radagast, on balance I think that he is a plus for the film and shouldn’t be dismissed as mere padding. Tolkien’s novels suggest that Radagast is a member of the White Council, one of the “white wizards” Gandalf met with down south. He lives in southern Mirkwood at Rhosgobel, a short way north of Dol Guldur. As Gandalf’s speech quoted above (not in the book) indicates, despite Radagast’s hermit-like ways and fascination with nature, he keeps an eye on things in the area. He also seems to maintain a system of bird messengers and spies for the use of the White Council. (In the novel he, not some passing moth, is responsible for the eagle Gwaihir appearing at Orthanc to rescue Gandalf.) Though Radagast never visits Dol Guldur in the book, he generally does the sorts of things that he does in the film. Although he perhaps contributes little in the first part of the film, we should withhold judgment on his importance to the plot until we see what he does in the second and perhaps the third.

The chase of the Orcs after Radagast’s sled, by the way, exemplifies one of the several lapses of causal motivation in the film. Why do the Orcs try to catch Radagast? They are specifically after Thorin, and the Orcs have no way of knowing that Radagast has any connection to the Dwarves. If they take off after every passing stranger when they are supposed to pursue a specific mission, these Orcs make very poor hunters. And while we’re on the subject, how does Radagast get all the way from southern Mirkwood, which is on the far side of the Misty Mountains, and find Gandalf so quickly?

A final note on Radagast. For those of us who were lucky enough to see Sylvestor McCoy play the Fool to Ian McKellen’s Lear during the stage tour, there is a bit of added resonance in their scene together.

Unjolly giants

The scene of the stone-giants has been criticized as well. They occupy four minutes of screen time, putting the Dwarves and Bilbo in extreme danger without having any real link to the plot. The scene’s only causal function is to give Thorin another opportunity to belittle Bilbo. The episode derives from a few brief remarks in the middle of the novel’s description of a terrible thunderstorm the group encounters in the high mountain pass:

When he [Bilbo] peeped out in the lightening-flashes, he saw that across the valley the stone-giants were out, and were hurling rocks at one another for a game, and catching them, and tossing them down into the darkness, where they smashed among the trees far below, or splintered into little bits with a bang …. They could hear the giants guffawing and shouting all over the mountainsides.

Douglas Anderson has suggested that by “stone-giants” Tolkien meant a particular type of troll; he mentions the “Stone-trolls of the Westlands” in Appendix F. (See the second edition of The Annotated Hobbit, p. 104.) If so, they would probably only be a little larger than the three trolls in the earlier forest scene. But whatever they are, they are clearly not fighting but playing a game. Moreover, the Dwarves, Bilbo, and Gandalf (who does not stay behind in Rivendell in the novel) are inside a cave when all this happens. Jackson could have chosen to leave out such a brief references, but he instead turns the creatures into immense giants made of stone, and they are having a flat-out battle rather than a game. I don’t think this was part of an effort to stretch the film into three parts but results from Jackson’s tendency to add or extend action scenes.

Finally, the film considerably lengthens the Goblin-town episode and includes a great deal more combat. In the book, Gandalf quickly kills the Great Goblin and leads the Dwarves and Bilbo in a race for the entrance, with a couple of skirmishes with small groups of Goblins. Again, I don’t think the expansion was created in order to necessitate a third part to the film. This scene had almost certainly been planned and shot well before the decision to ask Warner Bros. for permission to add a third part. Extending the scene is another instance of Jackson’s penchant for big action sequences, and especially battles. I find it a bit overlong myself, but many fans probably like it.

Azog the Defiler of Plots

There is, however, a plotline that does seem to me to be padding. The placement of scenes involving its action damages the narrative rhythm of the film as a whole. The plotline centers around Azog the Defiler, the “Pale Orc” whom Thorin grievously wounded in the battle at Moria (below) and who turns out not to be dead. Instead, he and his band of Orcs, bent on revenge and mounted on wargs (giant wolves) are hunting for Thorin. Making room for this line of action evidently led the filmmakers to cut other scenes that I, and undoubtedly some others, would have preferred to see.

Critics have pointed out a pattern of rescues and respites in both The Hobbit and LOTR. At fairly regular intervals, the characters get into dangerous situations and are rescued, often by someone completely unexpected and even unknown. They then spend a peaceful time with their rescuers before going on to the next challenge. This pattern is so consistent and evident that Ursula K. Le Guin termed it the “rocking-horse gait” of the books.

Obvious examples of down-time are the interludes in Rivendell in both books and the stay in Lothlórien in LOTR. These aren’t dull stretches. They’re occasions for introducing new characters, giving exposition, and bringing a new population with a distinctive culture into the mix of peoples uniting to battle evil. They’re about character development and revelation. They’re about showing off the beauties and wonders that make Middle-earth such an attractive, fully realized fantasy world. And between the battles and chases, they give us, as well as the characters, a bit of respite. This rescue pattern is one of the most basic structures of both of Tolkien’s novels. (I’ve devoted a chapter about it for my book-in-progress.)

The Azog plotline throws off the rescue/respite pattern (which Jackson’s team respected more consistently in LOTR). Worse, it tips the dramaturgical balance of the whole film. First there is the ten-minute troll battle, and then a pause while the group explores the cave. That moment of quiet action lasts only four minutes, and then Radagast shows up. I take this to be the beginning of the next scene of fear and danger, since the Brown Wizard agitatedly launches into a tale about his visit to Dol Guldur, presented as a flashback full of menace and threat. Almost as soon as he finishes, the chase begins. The Radagast scene to the point where the Dwarves’ group hides and Elrond’s Elves drive the Orcs away lasts 9:39 minutes, roughly the same length of time as the trolls scene.

The big Azog battle, in which the Defiler shows up in person and Thorin at last realizes that he’s alive, similarly comes very soon after the end of the huge Goblin-town battle and the concurrent Riddles in the Dark scene. The Goblins/Gollum action lasts 28:37. Once it ends, there’s an all-too-brief scene while the Dwarves and Gandalf think Bilbo has lost or has deserted the group, only for him to show up and explain why he has decided to stay with them (2:53).

Then Azog and his band arrive. The rather straightforward scene in the book, with ordinary Goblins and wolves trapping the company in some fir trees (not on the edge of a cliff), becomes a full-blown battle with Thorin nearly killed and Bilbo prematurely summoning up his submerged courage to save him (11:00). After three viewings, my basic response when the final forest confrontation with Azog begins is, Oh, not again! We’ve just had nearly half an hour of suspense and violence, with considerable variety and impressive filmmaking. The Goblin/Gollum scene should be the high point of the film. To have a shorter battle immediately after it makes the Azog fighting suffer by comparison while undercutting our memory of the earlier, longer one. I don’t think the Azog scenes in general add anything except brute action. Yes, they give Thorin a new revenge motive, but it kicks in only at the end of the film, and he already has plenty of dark motives with his hatred of Smaug and the Elves, particularly Thranduil. Far better to have stuck to Tolkien’s simpler version, ending the film with the group treed by generic Goblins and wolves and then get to the eagles’ rescue as quickly as possible.

The decision to end part 1 by moving away from the group and following a thrush to the Lonely Mountain is, I think, one of the more inspired additions to the story. As the thrush cracks a snail, the sound seemingly carries through the rock and into the cavernous interior, where we see a close view of Smaug’s eye emerging from a great heap of gold and popping open. Smaug is a great villain, unlike Azog, and I suspect his first conversation with Bilbo will be the equal of the Riddles in the Dark scene.

The Azog plotline also introduces a massive coincidence. Just after Balin has told the group the tale of the Moria battle and Gandalf and Balin have exchanged glances suggesting that they do not assume Azog is dead, there’s a cut to Azog’s Orcs appearing and discovering the group. We don’t know how long it has been since the Moria battle, but has this group of hunters been combing Middle-earth for Thorin ever since, while Azog cools his heels at Weathertop waiting for them to report to him? Possibly some sort of motivation for this will be supplied in part 2, but it’s really not a good idea to leave such a flagrant coincidence unexplained within this part.

Doing the numbers

Some have complained about the slow beginning of the film, which, apart from the early flashback to the kingdom of Erebor and city of Dale and their destruction by Smaug, takes place entirely in and around Bilbo’s home, Bag End. As has been endlessly pointed out, Bilbo’s race down the Hill to catch up to the Dwarves starts fully thirty-nine minutes into the film (not counting the open series of logos). To those interested in character and plot–and faithfulness to Tolkien’s book–this makes perfect sense. To those just waiting for the big action scenes, it’s frustrating. But the long exposition has to accomplish something that never challenged Tolkien: differentiating thirteen Dwarves. In the novel, only a few members of the group get any significant amount of characterization, and they mostly remain shadowy background figures whom we don’t have to visualize as individuals. But in a film they’re all there on the screen, and Jackson has to at least give them distinctive appearances. He goes further and assigns them traits, however simple, and on the whole does a good job of it.

To me, apart from the overly coarse behavior of the Dwarves (does Kili really have to be so boorish as to scrape his muddy boots on Bilbo’s furniture?), this early part of the film consists mostly of entertaining, lovely stuff. Kudos to Jackson’s team for keeping not one but both Dwarf songs, which nicely display the contrast of comedy and determination that underlies the group’s nature. The contract-reading scene and Gandalf’s attempts to persuade Bilbo to join the Dwarves’ quest are both entertaining and nicely revealing of Bilbo’s character. I particularly like the quiet conversation between Thorin and Balin, with Balin trying to talk Thorin out of the quest and Thorin revealing his reasons for confidence and hope. (In some ways, this makes little sense, given that it is Balin who later rashly sets out to try to retake Moria and ends up getting himself and his colony of Dwarves killed, but at this point it’s a minor matter.)

Again, though, there’s a problem of balance. So much of this fascinating material is crammed into the opening, and so much of the rest of the film is taken up with dangerous action scenes. It’s notable that the Goblins/Gollum sequence and the final Azog battle add up to 39:37, almost exactly the same length as the opening of the film up to Bilbo’s departure from home. The string of action scenes that begin with the trolls proceeds with only brief letups. A major exception is the Rivendell interlude, with the crucial White Council scene.

Then there’s the Riddles in the Dark, by common consensus the best thing in the film. It’s a relatively quiet and riveting scene, though here, too, Bilbo is clearly in danger from Gollum. Amusing though some of the latter’s antics are, he frequently drops from his Smeagol to his Gollum personality and tries to attack Bilbo. The part after Bilbo puts on the Ring is extremely well done, with him gradually realizing that Gollum can’t see him, and Gollum’s feelings at the loss of the Ring slowly settling from rage to anguish as his big eyes shift and look straight through the invisible Hobbit. Letting Bilbo see Gandalf and the Dwarves escaping and yet not being able to join them because Gollum crouches in the way is a clever touch–a slight improvement on the book, perhaps, since it makes it more plausible that Bilbo can find the group so quickly once he jumps over Gollum and escapes.

A sense of imbalance isn’t just my impression of the film. Timing the individual scenes reveals a remarkable pattern. Without logos or final credits, the film runs about 158 minutes. The mid-point would be roughly 80 minutes into it. The mid-point of a film usually comes at a particularly important dramatic turning point. In this case, at 80:40 minutes, the Elves drive the attacking Orcs away, leaving the Dwarves, Gandalf, and Bilbo safe and free to follow the secret passage into Rivendell. Thus the Rivendell interlude begins the second half.

I’ve timed the individual scenes and divided them up into action (threat, flight, battle) and quiet (conversations, meals, peaceful traveling) scenes. In the first half of the film, there are roughly fifty-one minutes of quiet scenes and 31 minutes of action. In the second half, the pattern is reversed with a surprising precision. The peaceful scenes run a total of 31 minutes, and the action scenes 48 minutes. (These figures don’t exactly add up to 158 minutes, because I’ve rounded off to the nearest half minute–and it’s not easy to time these things to the second!) Moreover, since the Rivendell scene opens the second half (being in the position of the Bag End scene for the first half), there are about 46 minutes of action in the rest of the film, versus 10.5 minutes worth of peaceful scenes. Hence my sense that the film is unbalanced.

Of course we would expect an adventure film to build toward bigger action scenes near the end, but the first part of The Hobbit has come close to squeezing much of its plot-centered scenes toward its beginning and the action ones toward the end. The stone-giants, Goblins/Gollum, and Azog scenes come all in a row. Imagine the Helm’s Deep battle in The Two Towers ending and the filmmakers ramping up another scene of combat. As it is, ending that part with Gollum’s quiet, menacing plotting against Frodo and Sam is far more effective.

Throughout the second half of The Hobbit, there are precious few pauses for simple conversations when the characters are not scared stiff. One seizes upon the few moments of this type with gratitude, as when Bilbo is about to leave the Dwarves and go back to Rivendell and ultimately home. He has a brief exchange with Bofur, who sadly realizes the truth of Bilbo’s statement that the Dwarves have no place where they belong and yet still summons the friendly good nature to wish the Hobbit well. More touching moments like that are needed.

Azog’s collateral damage

My impression is that Azog has muscled his way in by crowding out material of the quiet sort. Still images on the internet and shots in the trailers show moments that should be in this part of the film but are not. McKellen and others have mentioned in interviews that there was to be a flashback to Gandalf putting off fireworks at a Hobbit party long before and meeting the very young Bilbo. A production image of that scene (below) appeared on the internet, but there’s no such moment in the film. Logically, it could only come early on, perhaps in the conversation between Gandalf and Bilbo after dinner, to show the contrast between the adventurous, eager youth and the staid, middle-aged Bilbo who is determined to resist the Tookish side of his nature.

Some of the trailers and TV spots showed Bilbo at Rivendell, walking up some stairs and coming upon the statue holding the shards of Narsil (below). That blade, which we see cutting the Ring off Sauron’s hand in the prologue battle of The Fellowship of the Ring, will be reforged for Aragorn and renamed Anduril in The Return of the King. The idea that Bilbo might see the pieces of that sword so shortly before finding the Ring itself seems a strong addition to the film.

The frame I used as the top illustration in my earlier entry is from a trailer, but it is not in the film either. It showed Bilbo on a bridge at Rivendell, looking up admiringly at the building or landscape. That might have been part of the scene with Narsil, showing Bilbo wandering around Rivendell. There was supposedly going to be a conversation between Elrond and Bilbo, perhaps also part of the same scene with Narsil, but that, too, is missing. I would much rather hear what Elrond had to say to Bilbo, whether about the sword or Rivendell or Elves in general, than sit through yet more of Azog ordering his characterless Orcs around. (The brief scene, cut into the Rivendell interlude, in which one of those Orcs reports failure to Azog and is thrown to a warg to be devoured is particularly gratuitous and unpleasant. Yes, we need to know that Azog is still alive, but that revelation could have come later.)

I hope and expect that the cut scenes and others like them will be restored to their proper places in the extended-version DVD/Blu-ray release, already announced.

All this promising material was cut, evidently to give more room to Azog. What prompted the filmmakers to add him? I have no idea. In a press junket interview about a week before the release of the film last month, Philippa Boyens was asked about scenes added to The Hobbit’s plot. She responded:

I love Azog, Azog the Defiler. Because we just loved that name and he is a character that we just loved that back story and thought we can’t have him be dead, we’re going to keep him alive. So we enjoyed that … bringing him back. And I think we do that quite powerfully, he’s got a good journey to go on.

This baffles me, since ordinarily Boyens has specific, narrative-based justifications for changes made during the adaptation process. But how can one love Azog as a character? In the book, he’s an unusually large Orc who leads the troops at Moria. He has two lines of dialogue that just establish him as nasty, which is what one would expect of any Orc (see the “Durin’s Folk” section of Appendix A of LOTR). He survives the Moria battle depicted in the film, but Tolkien killed him off in that battle in LOTR. He is referred to in passing in The Hobbit novel as Azog the Goblin. The filmmakers have added “the Defiler.” Either the filmmakers thought they needed to pump up a story that already had enough action, or they for some reason did love this bit player of an Orc and let that feeling blind them to the damage he did to their plot. If by “journey” Boyens means a character arc, so far I don’t see any sign of Azog having one. I doubt he’ll reform.

Admittedly, a lot of fans of the film seem to like the Azog scenes. Many of them are probably unfamiliar with the novels and unaware of what is being left out or distorted. But I am far from alone in my opinion. Eric Wecks of Wired has written two short but perceptive commentaries, one on the trailer before he had seen the film and one after seeing the first part. He declares the Azog plotline and particularly the final battle as “wholly unnecessary.” But overall, like me, he admires the film. Many fans aren’t keen on Azog, either. TheOneRing.net has a large cache of fan reviews (1,815 last time I checked) They include one by Sirwen, who, although he or she likes the film and gives it 4.5 out of 5 “Rings,” lists several complaints. Number one is, “I understand that they wanted to have villain since Smaug is essentially MIA until much later in the story, but Azog just seemed random. I am assuming that he will turn out to be working for Sauron, because otherwise it makes no sense why he would wait a century for revenge.” I’m not assuming that Azog will turn out to be working for Sauron, though it’s possible. But Sauron is at this point in hiding, trying to regain physical form–at least, he is in the book. The Nazgûl are also in hiding. How would Sauron know about Thorin’s quest?

The Azog plotline is the only thing in the film that strikes me as truly superfluous. The screenwriters might not see it that way, but it also happens to be the only thing added to the story that has no justification in the appendices or anywhere else in Tolkien’s writing.

This doesn’t mean, however, that the notion of filling out the plot of Tolkien’s novel with other material was a mistake. So far, the importation of Radagast, the White Council, and the Dol Guldur menace work reasonably well and presumably will continue to do so. The scenes that I’ve mentioned as having been cut probably would have worked well, too. But if in the next parts Azog keeps popping up to have yet another attempt at killing Thorin, that plotline will become even more distracting, tedious, and, yes, padded.

[January 19, 2014: To find out where my speculations about the extended edition of Journey and The Desolation of Smaug, see my follow-up entry. Warning: spoilers for both Desolation and the third part, There and Back Again, plus some criticism of what I consider flaws in the film.

LeGuin remarks on the “rocking-horse gait” of Tolkien’s novels in “The Staring Eye,” included a collection of her essays, The Language of the Night: Essays on Fantasy and Science Fiction, Susan Wood, ed. (1974; New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1979), p. 173.

The generalizations I’ve made here about fan and critical opinions about The Hobbit were gleaned mostly through perusing many fans’ comments on Facebook pages and the Message Boards on TheOneRing.net, and reviews, often rather ephemeral online ones. I haven’t kept track of all of these and can’t give links, as I normally would.

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

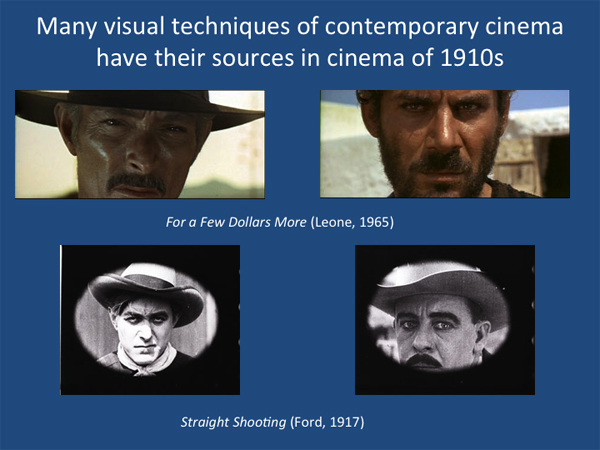

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.