Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to Georges Méliès

Kristin here:

This is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Georges Méliès (1861-1938). I doubt that the release of Hugo was timed to coincide with the occasion. If it were, no doubt the press kits issued by Paramount would have stressed the fact. Still, it’s a happy coincidence.

Hugo is receiving a lot of press attention, not surprisingly. If you’ve read more than one or two of the reviews and articles about Martin Scorsese and his film, you already know the two main hooks that journalists have hung them on. (Whether these originate from the pressbook or are just so darned obvious that everyone can figure them out, I don’t know.)

One, Scorsese is passionate about film history and preservation, so Brian Selznick’s best-seller quasi-graphic novel for children, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, based on the old age of early director George Méliès, would be a natural source for him to adapt. Especially so, since Selznick designed the illustration-heavy book to imitate a film, with series of drawings suggesting camera movements.

Two, the subject of Méliès’ pioneering special effects in the service of fantasy would be the perfect vehicle for Scorsese’s first venture into 3D.

True, no doubt, both of those points, and necessary to ease viewers with no knowledge of film history into this fairly sophisticated film. Not that the critics provide much help with the film’s many allusions to Parisian culture of the first decades of the twentieth century. There are real popular songs and posters for many silent films. I didn’t see any reviews pointing out that James Joyce and Salvador Dalí can be glimpsed fleetingly in Madame Emile’s café. (I spotted Joyce but not Dalí, only learning of the latter’s presence from the credits.)

Apart from signalling such references, however, there is a great deal more that one can say about the film. Some aspects of it are obvious, as befits a movie made in part for children. Others are more subtle, as befits a movie made in part for adults. I’ll offer a few observations here.

By the way, reviewers have made much of the idea that Hugo is not really for children, who would be bored and perhaps frightened by it. I suspect that children under about the age of 10 would be, but older children and teenagers, especially those who read books, should be intrigued by and enjoy it. Like Pixar films or The Simpsons, it’s the sort of thing that can be enjoyed by adults as well as children.

Movies within movies

Hugo is centered around Méliès’ work and tries to recreate something of the magic of the making and viewing of these films. Yet beyond this, it is steeped in the forms and subjects of pre-World War I cinema in general, to the point where the plotlines of Hugo subtly imitate early films.

A turning point in Hugo‘s story comes when Hugo and Isabelle invite fictitious film historian René Tabard (whose name is borrowed from the popular, Chaplin-impersonating teacher young student in Zero for  Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

In the book, the station’s Inspector, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, is a minor figure, glimpsed once from a distance by Hugo and finally coming to threaten him with arrest on page 412. His war wound and early life as an orphan are not part of his character. The Inspector is abetted by the café owner Madame Emile and the newsstand proprietor Monsieur Frick, sinister figures who appear only in this single late scene. They exist primarily to reveal the news of the discovery of the corpse of Hugo’s drunken uncle and to bear witness to Hugo’s thefts of croissants and milk from the café. The flower-shop girl, Lisette, whom the Inspector clumsily courts in the film, is not in the book at all.

What Scorsese very cleverly does is to expand these characters and have them play out what are in effect two brief narratives that could easily be imagined as early silent shorts. Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour) and Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) are transformed from nasty busybodies into a charmingly comic elderly couple whose tentative flirtation is thwarted by Emile’s aggressive dachshund. In two scenes, the dog bites Frick, once on the finger and once on the ankle. In the third scene, Frick solves the problem by providing a lady dachshund to divert the pesky pooch’s attention. One could easily imagine this as a short film from around 1906, making these two the leads and concentrating on their courtship. The dog could thwart the news-vendor’s approaches a few times before the happy ending is achieved with the introduction of the second dog.

The overbearing Inspector’s romance with Lisette is developed at greater length, and one could imagine it as a one- or even a two-reeler of the early 1910s. The Inspector’s attempts to court the young lady could be contrasted with his chivvying of the pathetic young orphan, actions that make her reject his advances. At the end, she might witness him relenting and treating the boy kindly, as indeed happens in Hugo, leading to another happy romantic conclusion.

In general, the situations and characters that we encounter in Hugo are common in early cinema. How many films, especially French ones, involve gendarmerie with their round, flat-topped caps, chasing mischievous little boys? How many melodramas revolve around poor children made homeless by their parents’ or guardians’ drunkenness? How many gags involve men stepping on musical instruments and smashing them? While the most explicit cinematic reference is to the Harold Lloyd feature Safety  Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

In a sense there are little topical and instructional films as well, with the reference to the dramatic historic accident at the Gare du Montparnasse on October 22, 1895, when a train crashed through its buffers and out the front wall of the station. (In reality, one death occurred: the wife of a news vendor who was minding the shop for her husband. Perhaps the Emile-Frick romance creates a happy ending of the cinematic variety to make up for that tragedy.) We also have the lesson in cinema history provided by Tabard. At one point in the flashback narrated by Méliès, apparent newsreel footage of World War I troops, touched up with hand-coloring, appears.

The film-like subplots all end happily, yet they are represented as being reality within Hugo. Perhaps for that reason, none of these brief narratives is the sort that Méliès would have used in his own films. They’re more like the non-fantastical comedies and chases made by Louis Feuillade and other directors.

The happy ending for Méliès occurs in Scorsese’s film, and yet it also happened in reality, if not quite the way it is shown here.

Cruelty, kindness, and the shape of the story

The structure of the narrative reflects the simplicity of each short film. It conforms well to the four-part narrative structure that I have claimed to be conventional practice in classical storytelling. Yet it also breaks neatly into two halves, the first about cruelty and the second about the sort of kindness that makes possible the happy endings. One can picture it as a V shape, with Hugo descending into greater loneliness and danger up to the mid-point and then climbing back toward happiness with the help of others.

Early on, both fate and other people are cruel. A museum fire has killed Hugo’s father, and his mother had earlier died of unspecified causes. Hugo’s drunken uncle wrests him from his home and school to live a fugitive life in the station. “Papa Georges,” whose full identity we do not learn until well into the film, seems unnecessarily harsh with the young Hugo. The Inspector obsessively hunts down stray children to send off to the orphanage. The bookseller Labisse, though generous in loaning books to Hugo’s friend Isabelle, looks upon Hugo with disdain. Even the two dogs, Madame Emile’s comic dachshund and the Inspector’s doberman are growling, threatening beasts.

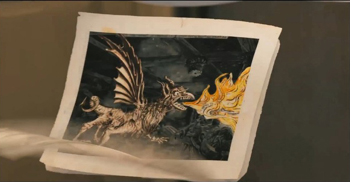

The automaton, of course, is the key to all. Once it provides the necessary clue by drawing the  famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

Ordinarily at this point in a Hollywood film, there would come a section where the protagonist struggles against obstacles to achieve his goal. In Hugo, however, the crisis at the center leads immediately to a series of kind actions. Upon returning to the station after the drawings discovery, Hugo runs into M. Labisse, who unexpectedly gives him a book that the boy and his father had read together. Then Madame Emile urges the Inspector to speak to Lisette, whom he has admired from afar, and coaches him in how to smile pleasantly. His smile, plus his halting success in his first conversation with Lisette, motivate his eventual ability to take pity on Hugo.

This scene leads directly to the scene at the “Film Academy Library” (a giant fictitious room full, apparently, of books on cinema) where the film historian and Méliès fan, René Tabard, appears. He will provide the screening of A Trip to the Moon which finally draws Méliès out of his depression to some degree. Yet the filmmaker still despairs as he thinks of the disappearance of his studio, the rest of his prints, and his beloved automaton. Hugo rushes off to fetch the latter, and after an extended chase sequence returns it to Méliès with the help of the Inspector, who saves the machine and the boy from an oncoming train. Recognizing something of his own youth in the distraught boy, the Inspector turns him over to Méliès for the happy ending.

The exception to the cruelty/kindess division of the film is Isabelle. In the original book she is not such a pleasant character, often arguing with Hugo. She does not have the joyous desire for adventure that the Isabelle of the film displays. The change is an improvement. In part this is because Hugo is such a very grim and forlorn character through much of the book. Portraying him that way in the visual medium of film might make his plight too pathetic to be entertaining. Isabelle’s early sympathy for him and fascination with the mystery of the automaton carries a strong thread of hope across both halves of the narrative.

In the lengthy epilogue there is a gala screening of some recovered Méliès prints, and a party is held. All the significant characters are present, with their satisfactory futures assured. Hugo will seemingly become a magician (as he does in the book). Isabelle has apparently found her hoped-for purpose in life, for she starts writing down the story that we have just witnessed. (In the novel, Hugo himself writes The Invention of Hugo Cabret, though he attributes it to the automaton.)

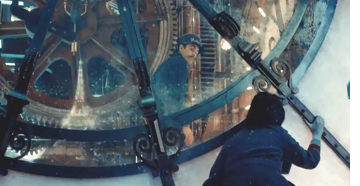

A machine-made ending

The film ends with a tracking shot, independent of the characters’ points-of-view, into a nearby room where the automaton sits, still and alone. As we approach its enigmatic face, the image fades out. The moment ends the imagery that has continued through the film, of humans as machines and  machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

The machine imagery goes further. The opening of the film dissolves from a set of moving clock gears to merge them graphically into a high view of the boulevards of Paris, which momentarily appears as a giant glowing, whirling machine with the Eifel Tower, symbol of the modern machine aesthetic, at its center. The repair of a wind-up mouse becomes the first small point of emotional contact between Méliès and Hugo. The Cinématographe camera/projector that fascinates Méliès even more than the moving images on the screen becomes the central machine, one which produces what one normally thinks of as the most private and mental of events, dreams.

All this machine imagery is fairly obvious, but it seems completely appropriate if we remember that this is, after all, a film partly for children. What I’ve been describing are things that a smart child could grasp, but the imagery and story aren’t done in anything like a condescending way.

The automaton, by the way, really did the drawing in the film itself, without CGI or other sorts of animation being used. For a three-minute film that ends with a fast-motion demonstration of its drawing capabilities, see here. For a demonstration of the restored Maillardet automaton in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, which Selznick used as his inspiration, see here, where it creates a drawing as complex as the one in the film. This automaton also revealed its origins when, after being restored, it signed its maker’s name.

[Dec 9: My claim that the automaton did the drawing without special effects was based on some statements by the company that made it (or more specifically, 15 versions of it). A recent article here interviews the film’s visual-effects supervisor Rob Legato reveals that the drawing scene was accomplished using magnets below the table: “The robot or automaton was not CG, although there were some CG doubles for some complex shots such as the train line fall. Prop builder Dick George constructed 15 automaton versions and some that actually could draw on paper. The VFX and special effects team solved the complex task by using magnets. Below the paper was a motion controlled magnetic system that traced the hand encoded drawing. The arm then moved to match the magnets and draw the famous picture. In a couple of shots if you could pause and really study the frame you might see that the pen nib, at those points, ‘is a ball point and not an ink well pen,’ comments Legato.” So the automaton did do the drawings, but not based on its complex system of gears and other clockwork visible inside it.]

How accurate is it?

Naturally the events of history are messier than the neat scenario of a mainstream film could encapsulate. Still, given the constraints involved, Hugo‘s modifications of the facts seem quite reasonable, and on the whole the general public will exit the theatre with a decent impression of Méliès’ career.

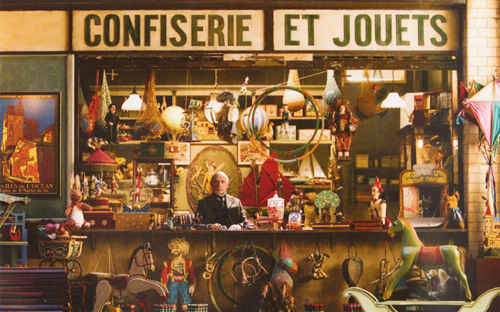

In fact he was married twice. Jehanne d’Alcy had been Méliès’ mistress well before they married in late 1925. They had both worked at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin before the cinema was invented, and d’Alcy appeared in many of Méliès’ films. (His first wife, Eugénie, died in 1913.) D’Alcy brought with her the ownership of a little candy-and-toy shop outside the Gare Montparnasse, which the couple transferred inside the station and ran together (see bottom). World War I did not cause the demise of Star Films. Méliès had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

As biographer Paul Hammond describes his decline, “Georges Méliès had become an anachronism, an artist left behind by economic and aesthetic developments.” In looking at Méliès’ late films, we might keep in mind that 1912 was the year of Albert Capellani’s remarkable serial adaptation of Les misérables. Max Linder was at the height of his popularity, and D. W. Griffith was making some of his finest one-reelers. The three great Swedish silent-era directors, Mauritz Stiller, Viktor Sjöström, and Georg af Klercker, all made their first films in 1912. The year 1913 would see a burst of cinematic inventiveness around the world, and Méliès would have seemed all the more old-fashioned by comparison had he continued to make movies. Nevertheless, he remains perhaps the only one of the very earliest generation of filmmakers whose work we return to not simply out of historical interest but for the fun and wonder of the films.

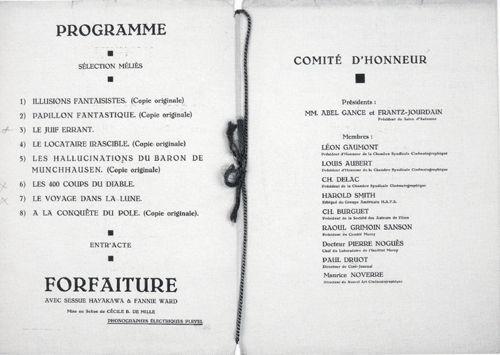

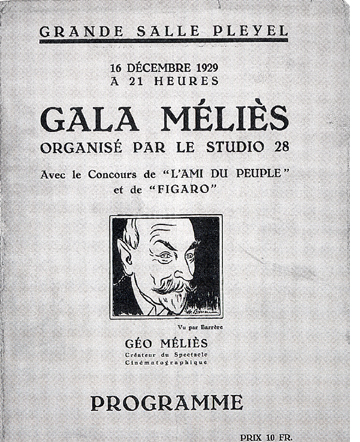

The rediscovery of Méliès began earlier than it does in Hugo, and it was more gradual. The mid-1920s were the nadir of his career. He and d’Alcy were living in a tiny flat in impoverished circumstances. In 1926, Méliès was notified that he had been made the first honorary member of the Chambre Syndicale Française de la Cinématographie–a trade organization, not an academic one like the fictitious “Film Academy” in Hugo. In 1929, J.-P. Mauclaire, director of the early art cinema Studio 28, found a batch of twelve tinted copies of Méliès films. New prints of the most damaged ones were made, and a screening of eight of them was held in a “Gala Méliès” that also included a revival of Cecil B. De Mille’s The Cheat:

In 1930 another program of Méliès films was shown, and in 1931 he received the Cross of the Legion of Honor. A benefactor provided Méliès and his wife with a larger apartment, and in 1934 he was made the honorary president of the Chambre Syndicale de la Prestidigitation. Ill health prevented him from pursuing some tentative filmmaking projects originated by admirers within the film industry, and he died of cancer in 1938. His granddaughter Madeleine ultimately became a champion in the revival of his memory. (For more on Méliès’ later life, see Paul Hammond’s Marvellous Méliès, pp. 80-85.)

Given all this, I think Scorsese and scriptwriter John Logan have done a reasonable job of condensing and tweaking the facts of Méliès’ story. The filmmakers also deserve considerable credit for showing the filmmaker cutting and splicing a strip of film involving a stop-motion effect. Méliès was long dismissed as not being much of an editor, having supposedly just stopped his camera and started it again to allow for the substitution of different items of mise-en-scene. We now know, however, that his amazingly well-matched transformations depended on eliminating just the right number of frames to create the magical illusion. He was a skillful editor indeed, and the filmmakers display that fact.

3D and Autochrome

Commentators naturally have stressed the fact that Scorsese has made his first 3D film. Up to now major filmmakers have embraced the technology, but most, like James Cameron, have worked in action genres. Could one of the “movie brat” generation redeem what has come to be seen as a technology that is rapidly losing its novelty value and perhaps its economic viability? The BBC even ran a story bluntly entitled “Can Martin Scorsese’s Hugo save 3D?” It and Steven Spielberg’s first 3D film, The Adventures of Tintin, have widely been seen as the crucial test of whether the use of 3D will continue to expand.

No doubt Hugo represents the best that can be done with current 3D technology. For once, every shot was filmed in 3D. Most 3D films, even Avatar, have at least a few images done with  post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

post-production conversion. (See the December, 2011 American Cinematographer article on Hugo, p. 56.) The filmmaking team went to extraordinary lengths to shoot as they wished to. They settled on using Arri’s new digital camera, the Alexa. The production required four cameras at a point when Arri was just beginning production, but the company managed to provide all four.

Cinematographer Robert Richardson has remarked on the idea of avoiding conversion: “If, as a film team, you’re not all working to best enhance in-camera the three dimensions then I would ask why have you committed to constructing a labour of love that someone else will eventually deliver to you via post conversion and say, ‘Here is your film.’ That might work for some projects and directors … but for me that choice felt insanely wrong. Commitment is required.”

Editor Thelma Schoonmaker has said of the 3D style “It’s not so much about stuff in your face—though there are a few wonderful shots like that. But more it’s about pulling the characters forward and feeling you’re in the room with them.” (Both quotations from Screen International [25 November 2011], p. 19.)

David and I went to see Hugo in 3D last week. Recently I have only seen a few 3D films: Herzog’s Cave of Forgotten Dreams, Wenders’ Pina, and Miike Takeshi’s Harakiri. Art-house films all, and apart from the Herzog film, where 3D serves educational rather than aesthetic functions, I didn’t think the 3D added much. James Cameron has said that Hugo is the best use of 3D he’s seen, and he should know.

I’ll admit that there are some terrific effects. The decision to have the Inspector’s doberman’s pointed muzzle coming out at us as it chases Hugo is clever and funny. But there’s still the blur and juddering of objects in the foreground, something that isn’t helped by the breakneck pace at which Scorsese “tracks the camera” through huge spaces or long tunnels. (Most of these shots involved as many special effects as actual camera movements.) I frequently wished in the course of the screening that I was seeing the film in 2D.

Apart from everything else, 3D pretty much necessitated that David and I move out of our habitual and preferred “front zone” of the theatre. Not only do 3D effects not work as well if you’re up close, but the edges of the screen are outside the frames of the glasses’ lenses. Turning your head when you’re sitting close and watching a 2D film is one thing; it’s quite another with those glasses on. So we sat further back. We also raised and lowered our glasses at intervals, checking out the amount of light being filtered out by those RealD glasses. It was quite a lot.

A few days later I went to see Hugo again, this time in 2D. The movie looked beautiful, with brighter images and more vivid colors. There was less blur in the fast camera movements. The depth cues in the images were strong enough to make such shots as the high-angle views down the vast clock tower impressive. And I was able to sit closer.

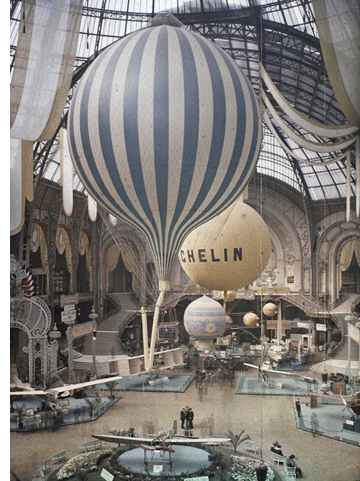

The brighter colors were important, since the filmmakers made an attempt to imitate a  photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

photographic color system of the early-cinema era. Specifically, Scorsese and Richardson aimed for the look of the Lumière brothers’ Autochrome system; this was the principal color system used in still photography until the 1930s. The digital grading used for Hugo played a big role in the attempt to achieve this look of early color. The American Cinematographer article mentioned above contains three sets of images demonstrating the stages of achieving the final look of Autochrome. A scan of one such set of images is available online. Just how authentic-looking the results are, I can’t say. (At right, a 1909 photo of an air show in the Grand Palais, Paris, by Léon Gimpel; for an extensive set of Autochrome photographs, see here.) Still, it’s a more interesting technique to those of us who aren’t fond of 3D, and I found that it gave the movie a color scheme that’s much more interesting than the standard look of films these days.

[Dec 9: A new interview with Robert Richardson by Bill Desowitz has just been posted here. It deals with 3D and Autochrome.]

Scorsese, journalists, and the legacy of Méliès

The reviews and coverage of Hugo in the trade and popular press have rightly emphasized Scorsese’s love of cinema history and his devotion to film preservation. He has collected high-quality 35mm prints of classic films, many of which are on deposit at the George Eastman House archive. Scorsese also helped found the Film Foundation in 1990 and the World Cinema Foundation in 2007. The latter organization has provided preservation work for films made in countries where either there is no national archive or where the archive lacks the funds and facilities for major restoration/preservation projects. Having first seen the Egyptian film The Night of Counting the Years (Al-mummia, 1969) in a battered 16mm copy, I was delighted to watch a beautifully restored 35mm widescreen copy at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in 2009. There is no doubt that Scorsese’s contribution to the film-restoration effort has been immense.

That said, I think some of the press coverage of Hugo has pushed Scorsese’s interest in preservation a bit too far in the case of Méliès, giving the impression that somehow the director has led a rediscovery of the early film pioneer as thorough as the one accomplished by Hugo and his friends in the fictional account. In The Hollywood Reporter’s story, “The Dreams of Martin Scorsese,” Jay A. Fernandez writes, “Over the years, Méliès has become a mystery himself, and even film buffs often don’t have a grasp of just how profound his contributions to cinema were, despite their efforts to piece together the scraps of his legacy. In this, he could not have better cultural archaeologists than Selznick and Scorsese.”

One might overlook a journalist (albeit one who specializes in entertainment news) believing that Méliès really was virtually forgotten among all but a few film historians before Hugo came along. But he goes on to quote Selznick, whose words might carry more weight, as saying of Scorsese, “Of course, Scorsese has been responsible for restoring the lost legacies of groundbreaking filmmakers. He is in the position of pointing the way for the public, showing us who has been forgotten and overlooked.”

That’s going a bit far. Admirable and important though Scorsese’s preservation efforts have been, and valuable as his video histories of topics like Italian cinema have been in bringing film history to a broader public, he cannot be said to have been responsible for rediscovering major filmmakers who have been forgotten. I doubt he would claim to have done so.

The work of Méliès has been covered in the basic histories of world cinema for at least the past fifty or sixty years. Indeed, the rediscovery of Méliès that began in the 1920s has continued ever since. Unfortunately, most of the coverage of Hugo passes over the diligent and successful work of archivists who have been the mainstay of that rediscovery.

The friends of Méliès

Méliès played a small but important role in my own early discovery of cinema history. During the spring of 1970, I was taking my first film course, a one-semester survey history, at the University of Iowa. As I recall, it was during that time that a representative of the Library of Congress came to campus and gave a talk on film preservation. He showed two hand-painted shorts, one of which was Méliès ’ Le Raid Paris-Monte Carlo en deux heures. The color was crude, to say the least. In 1905, without the benefit of a stencil, someone had daubed a dot of red paint onto the race-car in each frame, leaving the rest of the image in black and white. The result looked like a flickering, burning car was driving through magical landscapes. I found it quite fascinating, and that, along with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, were the films that really lured me into film studies and a career. I regret that the prints of Le Raid used for the DVD releases of Méliès ’ work have not included this clumsy but charming hand-coloring.

During my years in graduate school, the general claim was that something like a hundred of Méliès ’ output of around 500 shorts survived. By now, the number is more like slightly over two hundred. Occasional discoveries continue to be made.

In 2008, when Flicker Alley put out its monumental five-disc set, “Georges Méliès : First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913),” it contained 173 films—not quite all of those that were known at the time to survive. In 2010, the same company released “Georges Méliès : Encore” appeared, a single disc with 26 newly discovered prints. (I note that both are temporarily out of stock at Amazon, suggesting that Hugo has generated new interest in Méliès.) For our comments on the “Encore” disc, see here.

This flow of rediscoveries has been due to archivists like Paolo Cherchi Usai at Eastman House and Serge Bromberg at Lobster Films (two of the many archives contributing to the set released by Flicker Alley in the U.S.). David and I played a modest role in one such discovery. We spotted an ad in a film-collectors’ publication, offering for sale a nitrate original of a hand-colored Méliès film. We alerted our friend Paolo, who obtained the film; it turned out to be a lost Méliès title from 1899, in excellent condition.

Lobster Films appears in Hugo’s credits as the supplier of many of its clips from Méliès films. I wish more journalists would have made mention of Lobster. So far the only reference I have found is in Susan King’s story for the Los Angeles Times, “‛Hugo’ revives interest in Georges Méliès.” She includes a brief overview of Lobster, as well as a list of Serge’s suggestions of six Méliès films “that are must-sees.” (For our coverage of an encounter with Serge in Paris last year, including a 3D projection of part of a Méliès film, see here.) This article also contains the happy news that next year will see the release of a DVD containing the recently restored hand-colored version of A Trip to the Moon (bits of which are glimpsed in Hugo) and a documentary concerning the restoration, The Extraordinary Voyage.

Méliès has also been known to the public, at least in France and the U.S., though some lavish exhibitions and publications. Fortunately many of his designs and drawings have survived. Copies of them are tucked away in the armoire in Hugo. There are also numerous photographs and objects from the era. A 1991 exhibition at George Eastman House, “A Trip to the Movies: Georges Méliès Filmmaker and Magician (1861-1938),” was accompanied by an anthology of essays of the same name. In 2002, the Parisian show “Méliès, magie et cinema” resulted in a coffee-table book of the same title. In 2003, the Cinémathèque français held another exhibition, “Georges Méliès, magicien du cinéma”; it occasioned the publication of a large volume, L’oeuvre de Georges Méliès, which catalogued the archive’s holdings in gorgeous reproductions.

Historical reference books have not been lacking. In 1975, Paul Hammond published his Marvellous Méliès, a thorough and still useful book. It was followed by John Frazer’s excellent Artifically Arranged Scenes: The Films of George Méliès. There are other books on Méliès, too numerous to list in full here.

Since 1961, “Les amis de Georges Méliès,” a group founded by the filmmakers’ descendents (who are acknowledged in Hugo’s credits), have fostered the rediscovery and preservation of his legacy.

Now, go and watch Le Déshabillage impossible (1900, disc 1 of the Flicker Alley set), a two-minute film that remains as astonishing as it is hilarious. If you’re not a friend of Méliès now, you will be after seeing it.

[Dec 7: Thanks to Mark McElhatten for pointing out the mistake concerning the character Tabard in Zero for Conduct, a mistake which has apparently appeared in some reviews of Hugo.]

[Dec 8: Thanks to Paolo Polesello for reminding me that the rediscovery of Méliès included Georges Franju’s short film, Le Grand Méliès, 1952; it’s included in the five-disc Flicker Alley set.]

[Dec. 12: Today Variety posted a story about modern designers and special-effects experts who have been inspired by Méliès, in particular those who have eschewed CGI and opted for prosthetics, animatronics, and miniatures.]

Down in front! Notes from the Raccoon Lodge

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

There is one hypothesis that I find interesting because it is so minimal, yet sufficient. This is that nobody cares where he sits, as long as it’s not in the very front.

—Thomas Schelling, 1978

DB here:

Where do you like to sit in a movie theatre? If you’re like most people, you sit fairly far back, maybe all the way in the back row.

Sitting in the rear is the default for public gatherings, it seems. Thomas Schelling famously offered seven hypotheses about why people don’t fill up the front of an auditorium as fast as they fill up the back. His reflections were occasioned by his giving a lecture to 800 people, none of whom would sit in the first dozen rows. I know the feeling, though on a smaller scale. Seeing all your audience huddled so far away, you suspect you have cooties.

Schelling didn’t, so far as I can tell, offer a definitive answer, and his charitable reflections on people’s motives don’t keep me from finding the migration to the rear disquieting. In lectures, those distant auditors send off an air of foreboding. They seem poised to flee at the moment the talk reveals its fully catastrophic dimensions.

There’s a debate about whether students who sit in the rear get worse grades than those who sit close. (See below.) Speaking from experience, I’d be inclined to say that professors tend to give better grades to students sitting close because those distant, blurred ranks tend to give off an aura of desperate yearning to be anywhere but there. The folks up front at least seem to be trying to be part of things. The back-row brigade have not learned the great lesson of social life: Feign interest.

As this lead-in suggests, I’m a front-zone sitter. But that predilection comes at a cost.

Rebel without a Cause.

For lectures I always try to get a front-row seat, close to the speaker if possible, or centered if there’s to be a big visual presentation. This vantage point is great. If there’s flop sweat, you see it. If not, you get to enjoy consummate performance up close. I’ve sat in the front row for fine speakers like Chomsky, Pinker, and Bruner (to stay just with the Boston brain trust).

When a filmmaker does a Q & A, the front row is a must: you get a good chance at an autograph. The only time I regretted my prime front seat for a live event was for a concert—a John Zorn one. Within five minutes I expected my eardrums to bleed. After that overture I don’t think I heard anything else.

I saw back-row bias in the movies demonstrated dramatically in Madrid, where Tom Gunning and I went to a movie together. I forget the name of the theatre, but the film was Welcome to Veraz (1991), a Euroduction featuring, inevitably, Richard Bohringer and, less predictably, Kirk Douglas. Once we got inside, we found that our tickets were for specific seats. The cashier had assigned us, and all other patrons, to the same row—in the back, naturally. The absurdity of a dozen of us sitting side by side in a vast theatre was lost on the staff. Tom and I moved to the front, but everybody else piously stayed in the same pew.

You can study a less extreme case in graphic form in those remaining venues, mostly European and Asian, that still ask you to choose your seat on a chart. A glance shows you that everyone has piled into retreat mode, leaving lots of nice seats for you. Problem is, those overhead diagrams of the venue aren’t to scale, and so you don’t really know how close you are to the screen when you’re picking your seat.

When you were little, you didn’t mind sitting up by the screen. You sometimes fought to do it. But as we age, we seem to gravitate toward the rear. We’re even told that we should sit a prescribed distance back, usually the dead center of the auditorium. A distance of 2-3 times the screen height is a common recommendation. But Kristin and I are front-zone people. Speaking for myself, I like scanning the frame in great saccadic sweeps and even sometimes turning my head to follow the action. CinemaScope and Cinerama give your eyeballs a real workout.

I know that most people find this sheer madness. When the picture comes looming up, you do feel a little disconcerted and overwhelmed. But I find that I adapt in a minute or two. Even the keystoned angle isn’t a problem, partly because of our old friend perceptual constancy.

Note that I said front-zone. Not every theatre favors front-row sitting. Kristin and I once went to a screening of An Autumn Afternoon in a tiny Parisian house, one of those that seem to have been carved out of a loading dock. We sat in the front row, but that was a mistake. We could put our feet up against the wall housing the screen, and we reckon we watched the movie at something like a 45-degree angle.

Something a little more peculiar happened when we went to a Fan Preview of Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Firmly ensconced front and center, we were packed in by comic geeks, nerds, dorks, wonks and other damned souls, all determined to enjoy this movie. So we had the strange experience of hearing a line of dialogue and then, because its eloquence had a rich bouquet, hearing yelps of appreciation rolling back behind us, as row after row (a) heard it, (b) laughed, and (c) did an instant commentary on it. I can’t judge this movie objectively to this day.

So sometimes the front row isn’t ideal. Through experience, we know our local venues and favorite festival sites. In some theatres, such as most of our local Sundance screens, we sit 2-5 rows back, with C being a common choice. Still, the ticket seller usually does a double take and reminds us where the screen is. Then we get a shrug and something on the order of “Well, you won’t be crowded down there.”

Bologna Cinema Ritrovato 2008: Olaf Möller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, Kristin Thompson.

But in many venues the front row is perfect. Sitting there is hard-core moviegoing. I started aiming for it about forty years ago, when I began taking notes on every film I saw. If you sit too far back, how can you see your pad? You can’t be one of those idiots brandishing a lightbulb pen (even though I have some of those). The screen casts a little light that makes scribbling easier.

But even those who don’t write notes see the advantage of the front row. Nobody’s head looms in front of you. You’re less disturbed by latecomers. You have more leg room, and it’s easier to stretch out for a snooze. And should you wish to leave, the front row is the only one that lets you sneak out easily from any seat.

That last advantage, I should mention, can lead to trouble. Once at VIFF I was firmly planted in the front row, nose in book, as the auditorium filled. But I began to realize that these didn’t seem to be my tribe. There were more beards, nicer clothes, better hygiene, more sensitive faces. The place filled, and someone came forward to thank the sponsors for bringing a film about the efforts to save remote wetlands. I was in the wrong auditorium. To glares and mocking comments I slunk out in search of some obscure art movie I’ve forgotten.

Like everything else you do, front-row sitting sends a message. What message? For one thing, that signal of interest I mentioned in my classroom example. Somehow the front-row sitter seems to be more engaged, more eager to be swept up in the magic. You probably know the urban legend that the Cahiers du cinéma writers sat devoutly in the front row at Langlois’ Cinémathèque. We belong to a noble tradition, and we flaunt it. Chevaliers of cinéphilie, we risk eyestrain, neckache, back pain, and leg cramps for the art of cinema, or so we like to think.

Speaking of the Cinémathèque, back in 1970 I went to the Chaillot venue for a screening of Liebelei, to be attended by Luise Ullrich, one of the principal players. The place was full, but I had nabbed a nice spot up front. Before the film started, though, a Cinémathèque functionary started going along the front row asking every patron there a question. Everyone asked said no. I couldn’t hear the question at a distance, and perhaps might not have understood it if I had. So when the staff member came to me, I scarcely let him finish before declining. If non was good enough for other front-row denizens, it was good enough for me.

After the lights came down, Henri Langlois stepped onstage with Mme Ulrich. After a brief introduction, they descended. Only then did two people on the aisle surrender their seats for them. Then I realized all the French guys sharing the front row with me wouldn’t give up their seats even for the guest and the boss of it all. You see why I say front-row people are hard-core?

Le Pied qui étreint 1: Le Micro bafouilleur sans fil (1916).

I must report, however, that front-row sitting sends other signals too. Theatres in film archives have their regulars, and these folks, like me, believe that there’s only one good seat in any theatre, and they must occupy it. Fortunately, they mostly don’t agree on what that seat is. I’m always befuddled when the first person in the queue makes a dive for a seat far back and in the corner.

Alas, though, so many regulars have aimed at my target that every cinematheque has a coterie of front-row fans. And they’re perceived as, well, strange. I remember going to London’s National Film Theatre during a visit and getting in early enough to nab a prime front seat. Many regulars shuffled in to join me, and one seemed a bit miffed after the rank had filled. My neighbor told me apologetically that I was sitting in his friend’s seat. Of course I moved. Local loyalists have privileges. On another occasion a BFI staff member said that she worried that one of her friends might become “one of those sad front-row people at the NFT.” They didn’t seem unusually unhappy to me, but then they wouldn’t, for I am one of them.

My strangest contretemps with a front-row devotee came during a visit to the Munich archive. They were running Get Carter and I was the first entrant. I secured my front-row center post and settled down to read. (Front-row people show up early enough to finish substantial portions of Dostoevsky novels before the lights go down.) Suddenly an aged German lady, fortunately not Luise Ullrich, stood before me.

Seeing I was reading a book in English, she said, “Pardon me, you’re in my seat.”

I looked around and saw that we were the only people in the theatre.

“I always sit here,” she said. “I come every night.”

Nerdesse oblige. I relocated to the seat behind her. Moved by my gallantry, she twisted around to talk with me. I asked if she really came every night.

“Well, not every night. Not if they’re showing a Jap movie.” She looked severe. “I don’t like Japs.”

Comments about disloyalty to old friends leaped to my tongue, but I kept quiet.

Soon Get Carter started. The old bat immediately fell asleep.

She slept through the whole movie. I wanted to knock her upside the head. When I left, she was still out, snoring in my seat.

There are other drawbacks to the avant-garde spot in the movie theatre. Most people are bothered by handheld shots and 3D if they sit close, but I don’t find myself affected. Granted, I probably miss some of the surround-sound effects, which are apparently designed for a sweet spot far behind my territory. If it’s any compensation, the left/ right channels are really vivid for me.

The biggest drawback, though, is that you don’t have eyes in the back of your head. During Q & A sessions, you can’t track the conversation without twisting around in your seat. So I sit there as if I were listening to the radio. Worse, sitting close can render you oblivious to things going on behind you. If a fistfight broke out in that heavily populated rear section, you’d be in a poor position to watch it. Occasionally being in the front row makes me miss an outburst that was probably pretty entertaining but leaves me feeling like the guy in Pompeii who wondered why everybody was running past him just before a couple of tons of ash buried him.

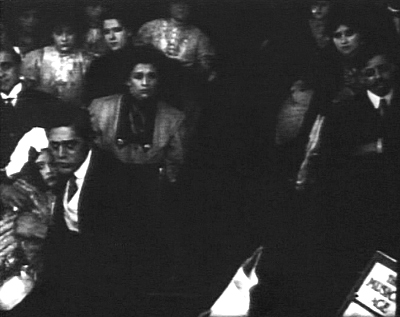

A Drunkard’s Reformation (1909).

On the obliviousness scale, my most memorable front-row experience came during another overseas festival. A visiting actress of consequence had directed some feature-length films, and the festival had arranged a screening of one. This entailed setting up a video projector and preparing, far in advance, electronic subtitles in the local language. When the director saw me planted in the pole position she said, “You shouldn’t sit so close. This movie is like Dancer in the Dark.”

No problem, I assured her; I’d seen that from the front row too.

No one joined me in the front. But there was a sizeable audience. Once people had settled down, her introduction explained five things, each one adding to a litany of doom.

(1) She played the protagonist.

(2) The film was improvised.

(3) It was shot handheld.

(4) The actors were her friends.

(5) It was a satire on the superficiality of Los Angeles life.

She wished us a good screening and said she’d see us afterward for a discussion.

The film was as dire as I’d feared. When the lights came up I noticed that nobody was setting up the microphone on stage. I turned around. The technicians were putting away the projection equipment. I was the only viewer who’d hung on to the end. Needless to say, there was no auteur and no Q & A.

Despite all the drawbacks of front-zone sitting, I feel vindicated by a recent revelation. A review quotes James Wolcott’s acount of Pauline Kael’s preferred viewing station.

We take up mortar position in the back row. Pauline nearly always sits in the back, often right beneath the projectionist’s portholes, flanked by fellow critics on her squad. . . . (The auteurists — those ardent members of Andrew Sarris’s Raccoon Lodge — tended to huddle closer to the screen, as if to meld mind and image into a blissful, shimmering mirage of Kim Novak with her lips parted.)

I rest my case.

Thomas Schelling’s reflections on lecture-hall seating open his classic Micromotives and Macrobehavior. Among his more entertaining speculations on why people sit in the back is this one:

A fourth possibility is that everybody likes to watch the audience come in, as people do at weddings.

For some research on whether students sitting up front get higher grades, go here (abstracts only) and here. Jonathan Cohen provides a nice analysis of the research on perceptual constancy here. 3D has rekindled debates about where to sit; for one exchange among cinematographers, go here.

Le Pied qui étreint is discussed in more detail here.

Joe Dante at University of Wisconsin–Madison, November 2011. Photo by Jeff Kuykendall. For more on Dante’s visit, go to this earlier entry and to Jeff’s coverage here.

PS 23 January 2012: Please note that another couple likes to sit in the front row (from here).

You are my density

DB here:

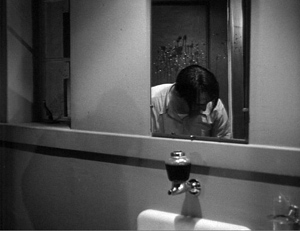

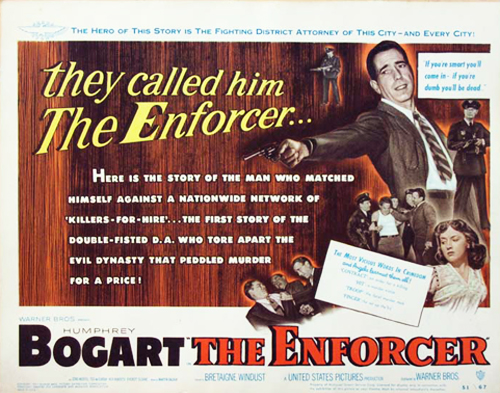

The mobster Joseph Rico is in protective custody; tomorrow he testifies against the big boss. But Rico fears reprisals, so he decides to escape. While a sleepy cop guards him in the washroom, he bends over the sink and rinses his face.

Turning so suddenly that water spatters on the mirror, he grabs the cop in an armlock and slams his head against the sink, just below the frameline.

Rico turns to the window to make his escape.

What interests me in this passage from The Enforcer (1951) is not just what happens in the mirror but also what happens on it. While Rico belabors the cop’s head, we’re given a chance to notice the splash of water that hit the mirror when Rico whirled to the attack. While the action is moving forward, we’re reminded of what had triggered it.

We get a sort of parallel reminder in the next scene, when we see the wounded cop again. He’s sporting a big bruise on his left temple, a souvenir of Rico’s assault.

Pfui. Details, you might say. Or you might (correctly) instance this as another case of Charles Barr’s enlightening notion of gradation of emphasis. But it’s worth getting a little more specific, because even this simple scene (by non-auteur director Bretaigne Windust) offers us something to think about, and something for today’s filmmakers to try.

Most films today don’t fully exploit the visual dimension of cinema. True, we have dazzling CGI and fancy camera moves. But when it comes to less flamboyant scenes, directors have limited their options by relying too much on stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk. There are other aspects of visual storytelling that today’s filmmakers neglect. One aspect is the possibility of gracefully moving actors around the set in a sustained fixed shot. A specific tactic I’ve mentioned before is the Cross, and another involves ways to get people into a room. The option I’m going to sermonize about today is what I’ll call scenic density.

By scenic density I mean an approach to staging, shooting, and cutting in which selected details or areas change their status in the course of the action. I don’t count the bustle of background business, all that street traffic that is so much pictorial excelsior in our movies. Nor do I refer to stuffing the setting with desk and kitchen flotsam, allusive pop-culture posters, and the other distinctive “assets” that will be exploited when the film’s world gets transposed to a videogame. I mean something more expressive and intriguing.

Using it up

Go back to the Enforcer scene. The shot’s composition creates a delimited zone of action. The guard cop is framed tightly in the mirror. When the fight breaks out, it’s initially framed in that mirror–a narrowing of visual importance. Moreover, the shot is designed to highlight the spatter on the mirror. It’s fairly prominent, stuck near the center and, providentially, in the spot that the cop’s head initially occupied. The lighting picks out the drips, and in a shot where the figures move in and out of frame, there isn’t an equally constant center of interest. We’re probably concentrating on Rico’s punishing of the cop, but the dribbles of water remain prominent enough to claim our interest, especially when Rico passes out of frame.

So here’s my first condition for scenic density: the shot keeps several items of dramatic significance salient in the composition.

This technical choice asks the filmmaker to think of the frame as a field of dynamic masses and forces. Such an idea was part of the aesthetic of “advanced” European and Japanese silent cinema of the 1920s. Many directors explored this dynamism, often aided by low angles and wide-angle lenses. Here are examples from Eisenstein’s Old and New and Murnau’s Tartuffe.

This pictorial density became especially prominent in American cinema during the 1940s, when low angles, wide-angle lenses, and locations and smaller sets encouraged cinematographers to pack their compositions snugly, as in this shot from Panic in the Streets.

Boris Kaufman, cinematographer for Jean Vigo and Elia Kazan, summed up the principle:

The space within the frame should be entirely used in the composition.

Since cinema is a time-bound art, however, the salient elements in the shot could and should change. But if the frame space is wholly “used,” what room is there for change? The only options are to have the using-up elements shift position, or to reveal that the frame isn’t used up.

Vivid instances, also from the 1940s, can be seen in Anthony Mann’s work, both with and without John Alton. Generally, Mann used the new fashion for depth composition, especially big foreground elements, to heighten scenes of violence. Physical action becomes more aggressive if people rush the camera and halt in tight close-up, especially because wide-angle lenses tend to accelerate movement to the foreground. Mann thrusts violence abruptly to the camera with an almost comic-book effect, as when the club owner is shot in Railroaded, or a man is flung to the floor in Raw Deal.

Even when this in-your-face tactic isn’t employed, the Mann films find ingenious ways to develop what seem to be completely locked depth compositions. In Border Incident, Ulrich confronts the Mexican government agent Pablo, disguised as a Bracero. A looming depth shot is followed by a reverse shot displaying a compact composition.

Is the frame space fully used? The second shot above is opened up when Ulrich leans forward to sock Pablo, creating a vacant spot on the far right for Pablo to fall into. The shot is emptied and re-filled, dense once more.

Memories, memories

Aha, you may be saying. Density just refers to squinchy, fussy shots from an era that favored cheap flash. No. The Enforcer shot isn’t all that cramped. Of course the blank, unchanging walls serve to highlight the mirror-reflected fight and the water dribbling down the glass, but you can imagine how much more jammed and skewed Mann’s treatment of Rico’s escape would be. As for the flashier depth, I just needed some clear-cut cases of density, examples in which details and spatial zones become starkly salient. Now I want to suggest that scenic density can be achieved in something more spacious, even monumental. That has to do with time and memory.

Part of what gives the Enforcer shot its interest is the superimposition of two moments of action in a single space: Rico’s diversionary turn from the washstand, recorded in the splash he made on the mirror, and the struggle taking place a few seconds later. A further trace of that struggle and that splash is visible in the bruise on the cop’s head in the next scene.

That dripping spatter can stand in for the second quality of spatial density I want to highlight: Its capacity to coax us to recall earlier action in the locale. Characters leave their marks and spoors in the space, and those get activated as memories. Unlike the slick surfaces of today’s settings, in classic films the settings can bear the impress of human transit, leading us to recall bits of behavior and emotional states. Let me illustrate from Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

It’s Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, and Gestapo Inspector Ritter is questioning Mrs. Dvorak, the vegetable seller who could identify the woman who misled the officers pursuing an assassin. Torture, or at least what we think of as torture, hasn’t started. She is simply standing in front of his desk as he brandishes his riding crop in the manner of a good movie Nazi.

When Mrs. Dvorak denies knowing the woman, Ritter taps the back-rest of the chair. It simply falls off, and we realize it’s not fastened to the chair.

Ritter says, “Pick it up again.” Now we realize that intimidation has been applied for some while; Ritter has made the woman stoop to replace the back-rest many times. She does so again as the camera tracks back. This is nicely detailed too. She starts to pick it up by bending over, finds the effort too painful, and then goes to her knees to pick it up–just as Ritter taps his riding crop against her hand, a teacher gently chiding a slow pupil.

As Mrs. Dvorak rises to put the piece back in place, the camera pans slightly right to pick up the woman bringing in a tray. Happily Ritter sniffs the coffee jug and resumes questioning the old woman.

Cut to a shot of her by the chair. “Let’s start from the beginning,” says Ritter, offscreen. Unthinkingly Mrs Dvorak starts to rest her hand on the loose slat, forgetting that the top slat is unattached. It’s a natural response. She’s been standing there for a long time and would like something to rest on, and the chair is temptingly close. (Presumably, that’s its purpose, to taunt the unwary prisoner forced to stand a long time.) Remembering just in time, she yanks her hand away. If she knocks the back-rest off, she’ll just have to pick it up again.

Cut to Ritter. “Don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak. I’m prepared to—”

Cut to Mrs. Dvorak. As he continues, “–devote to you all of tonight,” she forgets herself again and relaxes her hand, this time on the back-rest. It falls off, making her start.

She looks up as Ritter says, offscreen: “Even longer if necessary.” Cut to Ritter, gesturing with a piece of sausage and saying, coaxingly, “Well?”

Slowly she goes to her knees again as the camera tracks in on her.

Back to Ritter: “That’s the girl.” Back to her, rising in pain to replace the back-rest.

The scene concludes with Ritter reminding Mrs. Dvorak that she’s in Gestapo headquarters. She acknowledges that she doesn’t expect to leave without giving information. He starts his questioning all over again as the scene fades out.

This quietly suspenseful scene establishes a bit of furniture as a key prop. Once the faulty back-rest is marked for our notice, we’re expected to remember that it’s a means of intimidation–something that Mrs. Dvorak, in her anxiety about refusing to aid the Nazis, twice forgets. Lang’s shots, simple and uncrowded, makes the chair, like the spattered mirror in The Enforcer, preserve the trace of human activity. Yet it’s more acutely integrated into the scene’s drama than the mirror, and remembering how it was used earlier makes us wait tensely to see how it will be used again.

Long-term density

Several scenes later, the Nazis threaten to kill four hundred Czech hostages if the assassin isn’t turned over to them. Mascha Novotny has set out for Gestapo headquarters to denounce the man she helped, but she changes her mind and decides not to betray her country. She will only plead for her father’s life. Once more we’re in Ritter’s office.

Centered in the frame, standing out as a pale oblong against the grayer background, the fateful chair is made salient during Mascha’s conversation with Gruber. I suspect there’s a sort of spatial suspense here–will she move to the chair and dislodge the precarious piece of wood?–but more important, I think, is the fact that the chair ineluctably reminds us of Mrs. Dvorak and her quiet resistance to pressure.

Ritter leaves to consult his superiors. When he comes back, a new composition keeps the chair prominent and lends a new centrality to the clock on Ritter’s desk, surmounted by a snarling cat or something like it. (It’s visible in shadow in the earlier scene with Mrs. Dvorak.) But now the camera arcs to minimize the Dvorak chair and show the beast and Ritter targeting Mascha.

Soon enough, as if to make sure we remember, Mrs. Dvorak is brought back in, having undergone serious torture. The camera positions reactivate our memories of the earlier scene.

As she continues to lie to protect Mascha, Mrs. Dvorak never touches the chair. Although she has been tortured, she seems wearily defiant, as if her refusal to aid the Nazis has given her some strength: no need to lean on the chair now. As a final cue to our memories, Lang has Ritter play once more with his riding crop, letting its shadow fall on her heart.

The threat is clear: For lying, the old woman will pay with her life.

The chair reappears in a later scene, but I’d argue that then it serves more as a pointer to another prop. The resistance movement fights back by framing Czaka, a beer baron sympathetic to the Nazis, as the assassin. Lang could have explicitly recalled the questioning of Mrs. Dvorak by having Czaka lean on the slat and knock it off. Instead, the composition makes Ritter’s clock more important than it was in earlier shots. As Czaka tries to defend himself, the framing blocks our view of the chair but emphasizes the snarling catlike creature on top of the clock. And the chair has shifted a little off and become a bit darker; it’s no longer as salient.

This cluster of scenes from Hangmen Also Die illustrates how scenic density can add layers to a film. One scene recalls another not only by similarity of situation and locale but by tangible marks left on it by earlier action. Having seen Mrs. Dvorak subjected to Ritter’s oily intimidation, we generally expect something like it to be applied to Anna. This conventional situation is given a rich, concrete presentation by the repeated camera positions and the simple chair that, unmoving, enters into the drama.

Of course as a Hollywood director, Lang was pressured to reuse sets and camera setups. That saved money and time. But he turned such repetitions to his advantage by letting certain objects come forward at crucial moments. They not only become part of the drama but prime us to remember them, and what they revealed, in ensuing scenes. And even though Lang never pursued the aggressive, packed deep-focus of other directors working in the 1940s, he shows how roomier, less pressurized compositions could still be charged with echoes of earlier bits of behavior.

Is this sort of visual-dramatic economy, calling on precise memories of concrete actions, lost in today’s American cinema? I suspect it is.

In studying Hangmen Also Die, I was curious about a perennial problem. Was the byplay with the chair a Lang invention on the set, or was it some version of the script, or in the original story by Lang and Bertolt Brecht?

The film didn’t have a secret script, as the poster says, but the sources do remain a bit obscure. A draft of the original story signed by Lang and Brecht, in that order, exists. It indicates only that the greengrocer, called Frau Blaschke, is subjected to eight hours of “the usual Gestapo brutality” and refuses to identify the girl. There were other drafts of the screenplay, but I don’t have access to them, if they exist, and standard sources on Brecht in Hollywood don’t mention this scene’s details.

Somewhere along the line, though, the chair-back business was concocted. I found the shooting script signed only by John Wexley (Brecht claimed that he was robbed of credit) and annotated in pencil, perhaps by Lang. That script indicates that Ritter’s room contains “a vacant chair with its seat close against desk.” and Mrs. Dvorak is standing beside it as the scene begins. Much of the dialogue is the same , with some slight changes notated in pencil, possibly by Lang. But the camera movements indicated are different from those in the final film, and more importantly so are the actions. After Mrs. Dvorak claims that she doesn’t know the woman who helped the assassin, we read the following. I indicate pencil notations with {}.

In her fatigue, she places hand on back-rest of chair. But its dowels are loose and back-rest clatters to the floor.

RITTER (saccharine): Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak.

CAMERA MOVES IN CLOSE as she obeys, stooping with painful fatigue–she has done this many times tonight.

RITTER: Now put it back in place, Mrs. Dvorak.

(She does so)

As Ritter questions her:

MED. SHOT – MRS. DVORAK. Without thinking, she is about to place hand again on loose back-rest–when she remembers and jerks back.

RITTER’S VOICE: Now don’t be nervous, Mrs. Dvorak…I’m prepared to devote to you all of tonight–and even longer, if necessary.

Mrs. Dvorak, unconsciously reacting to this, once more rests hand on chair. {She jerks back but} The piece of wood clatters to the floor.

MED. SHOT – RITTER. Ritter waits patiently; when she doesn’t move, inquires:

RITTER: Well…?

CAMERA PULLS BACK to INCLUDE Mrs. Dvorak, who stoops to repeat painful routine. Ritter smiles approvingly.

RITTER: That’s the girl.

Nothing here is indicated about Ritter’s riding crop, nor does he initially knock the back-rest off the chair. Mrs. Dvorak does it herself, accidentally. And the scripted line is “Pick it up, Mrs. Dvorak,” not, as in the finished film, “Pick it up again, Mrs. Dvorak.” The film version makes it clear that the byplay with the backrest is part of Ritter’s softening-up technique, something indicated in the script but not spelled out.

The later scenes in the film show other differences, mostly additions of things not mentioned in the shooting script. For instance, the script doesn’t mention the shadow of Ritter’s riding-crop. But the excerpt shows that the shooting script points toward some of the detailing we find in the finished film. It provides the sort of nudges that a director, especially one as oriented to gesture as Lang was, could elaborate on the set.

The Lang/ Brecht story has been published as “437!! Ein Seiselfilm,” in The Brecht Yearbook vol. 28: Friends, Colleagues, Collaborators, ed. Stephen Brockmann (2003), 9-30. The passage I mention, kindly translated for me by Ben Brewster, is on p. 16. Broader background on Brecht’s adventures in Hollywood can be found in James K. Lyon, Bertolt Brecht in America (Princeton University Press, 1980). Chapter 14 of Patrick McGilligan’s Fritz Lang: The Nature of the Beast (St. Martin’s, 1997) offers an account, mostly relying on Brecht’s viewpoint, of the making of Hangmen Also Die. The shooting script is in the John Wexley collection of the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research and the State Historical Society here in Madison. Thanks also to Marc Silberman, renowned Brecht expert, for advice.

A variation on a sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film

Kristin here:

On April 21 a young Spanish film student uploaded his remarkable little film, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 onto Vimeo. There it languished, like so many contributions to the internet, good and bad. In the first four months of its presence on the site, it attracted 17 views.

Then, on August 17, Variation was viewed twice and earned its first “Like.” (One has to be a member of Vimeo to Like a film, so one cannot assume that none of its viewers to that point had enjoyed it.) That first Like, and perhaps both views were by Kevin B. Lee, best known for his many video essays on classic films. (See here for an index; I contributed the commentary for the La roue entry.) Over the next week and a half there were five additional views, four on August 28. I suspect some or all of these last ones were repeat visits by Kevin, since on August 31 he was the first to post an essay on Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 (hereafter Variation), along with some information on its maker, Aitor Gametxo.

The immediate result was a flurry though not a stampede of views: 33 on August 31, along with a second Like; and 15 on September 1, with a third Like. One of those views and the third Like were mine. On September 2, there were 12 views, dwindling to 2 on September 3 and 1 on September 4.

(Among the viewers after the Fandor entry was Evan Davis, University of Wisconsin-Madison film-studies alumnus, who read Lee’s blog, watched the film, and passed the links along to us. Thanks, Evan!)

It’s a pity that more attention has not been paid to this charming, clever, and informative film. Not only would people enjoy it, but it could easily be used as a tool for those teaching, or indeed researching silent cinema. So here’s my bid to help it go viral.

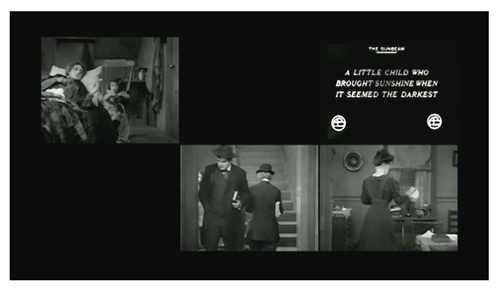

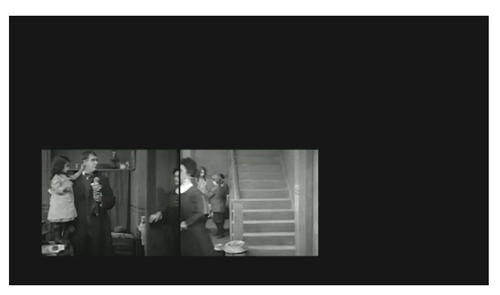

Variation is a found-footage film based on Griffith’s American Biograph one-reeler The Sunbeam, made in December, 1911, and released on March 18, 1912. It is not among the most famous of the nearly 500 one- and two-reelers Griffith directed at AB between 1908 and 1913, but it’s better known than most. In the opening, a sick mother dies, and her little girl, thinking her mother is asleep, goes out into the hallways of their working-class apartment building. She tries to find someone to play with, but everyone rebuffs her until she manages to charm two lonely people, a bachelor and spinster, who live opposite each other on the floor below the child’s home.

Aitor noticed three key things about the film. First, the action takes place in a very limited space, with the three apartments and hallway all close to each other. Second, the doorways through which the characters pass between these rooms are on the edges of the screen, so that when they exit through the doorway in one shot and after the cut enter the space on the other side of the doorway, there is often a sort of elusive match on action formed (what I termed a “frame cut” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 205 and figures 16.36 and 37). Third, and perhaps most importantly, Griffith was intercutting actions that were happening simultaneously, so that at many of the cuts, he jumped from the end of an action in one space back in time to catch up with what had been happening in another space. At times he would jump back twice if simultaneous actions were happening in three spaces.

Aitor has taken the individual shots and redone them, putting them into a grid of six small frames, three on the bottom and three at the top. Scenes in the child’s upstairs apartment are shown only in the upper left, the top of the stairway in the upper center, and the two apartments on the ground floor at the sides, with the hallway and bottom of the stairs between them. (See above.) These are roughly the actual positions these spaces occupy in relation to each other in the building represented in the film. The shots run in their true temporal relations, so that there is no jumping back.

I suggest that before reading further, you watch The Sunbeam, especially if you have never seen it before. It would be impossible, I think, to entirely follow the story just from seeing Variation. The shots are so reduced in size to fit into the grid that small but important gestures and details get lost. Here is the original film, from YouTube.

With Aitor’s kind permission, we present his take on Griffith’s one-reeler. (The Sunbeam runs about 15 minutes, but due to the simultaneous presentation of many shots, Variation is only about 10 minutes.) Click on the “Vimeo” logo in the lower right corner for a larger image:

A fascinating film, isn’t it? I think many viewers would reach the end of Variation and wish that the same sort of presentation could be created for other films–at least, early ones that are short enough to make such rearrangement viable. Kevin Lee is enthusiastic about the idea: “Imagine this multi-dimensional, real-time approach being applied to footage from other films, as a way of not just mapping out scenes in a movie, but also gaining insight into filmmaking technique.” It might be possible, but the six-rectangle grid used here would not work for very many films. Aitor has chosen the ideal film for such an approach. Not only are there a limited number of significant characters, but they also live in the same building, with three rooms and a hallway, all viewed from the same direction, making them fit perfectly into a “doll-house” style scene.

Had Griffith not routinely shot directly toward the back wall in all his sets, placing the shots directly side by side across the grid would not work, at least not so neatly. Many other directors of this era were exploring shooting into corners and having doorways for entrances and exits centered at the rear. Perhaps filmmakers like Aitor could still place different shots side by side, but the actors’ movements from one space to another would not be so smooth. One of the attractions of Variation is that those movements are smooth, and as a result the action plays as if it were part of a continuous, “real” film.

Even other Griffith films shot in the style of The Sunbeam would be far more difficult to lay out on a similar grid. Longer rows of more rectangles would need to be added, or the upper row would have to represent actions taking place at a distance and the lower one actions taking place within a building. (I’m thinking here of something like The Lonely Villa, where action in a series of contiguous rooms is intercut with the husband’s race from a distant locale back to his house.) The placement of the bachelor’s room opposite the spinster’s, on either side of the hallway through which all of the minor characters pass, is crucial to Aitor’s project. A complex film with many characters and locales might create a grid with rectangles too small to be grasped by the viewers. Ways of indicating techniques like flashbacks would have to be devised. And of course, not all films contain simultaneous action.

Variation has some technical disadvantages. The titles appear in the upper right corner of the screen, since no locale opposite the child’s apartment is ever shown. The titles are small and difficult to read, and since they pop up simultaneously with the action, it’s almost impossible to read them anyway. One cannot tell where the titles originally came in the flow of shots, though one can always check the original film. Another problem is the cropping of the images on all four sides. The DVD copies are somewhat cropped, and more of the image is eliminated in the Variation frames; the action of the little heroine hiding a hairpiece in the spinster’s home, an important motivation for later action, can barely be grasped because it is so small a detail and happens at the very bottom of the frame; in the DVDs it can be clearly seen.

The Griffith Project and our knowledge of his techniques

I do not intend by any means to diminish what Aitor has accomplished when I say that the three main techniques he works from have been known to Griffith scholars for years. Variation offers a new way of examining and explaining those techniques.

Griffith has, of course, been one of the most closely studied filmmakers in history. A vast summary of and contribution to the research on Griffith was recently compiled by “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” film festival in Pordenone, Italy. From 1997 to 2008, the festival mounted a nearly complete retrospective of Griffith’s work, hampered only by those films which still exist only as negatives or in other forms that could not be projected. A team of experts divided up the work and wrote extensive program notes for every single film Griffith made, whether it was shown at the festival or not. The notes, some more general essays, and Griffith’s writings were edited into twelve volumes jointly published by the festival and the British Film Institute (1999-2008). I had the privilege of contributing notes to most of the volumes, and although I cannot claim to know Griffith’s entire œuvre intimately, I got to know the films assigned to me quite well and learned a great deal about his methods.

The program notes for The Sunbeam were written by Griffith specialist Russell Merritt (Volume 5, 2001). As these excerpts from his description of the film’s setting indicate, the doll-house arrangement of the sets in The Sunbeam were distinctive, but not atypical of Griffith’s approach:

This was the second of Griffith’s three December tenement films (falling between The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls); spatially it is his simplest. Griffith uses only five setups (fewer than half what he works with in The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls.), but far from feeling cramped or monotonous, the three rooms and two hallways spaces seem perfectly designed for the playful romps, the practical jokes, and the unfolding of the gentle love story.