Archive for the 'Readers’ Favorite Entries' Category

Do not forget to return your 3D glasses

(Yours for $11 in theaters equipped with RealD systems, but you don’t get the pouch they came in at the opening midnight screenings)

Kristin here:

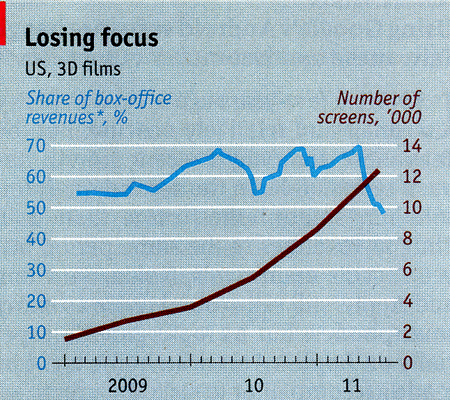

As 3D really took hold in the wake of the release of Avatar in December 2009, we got used to hearing that roughly 60% of a blockbuster’s income came from 3D. This summer the figure has hovered around 40%. Both figures are highly misleading. How much does 3D really bring in?

Yes, 40% of the total amount for almost all big 3D films this summer was for tickets sold for 3D screenings. But looked at another, more realistic way, 3D films as such made far less than that for their makers and the theaters that showed them.

That’s because a lot of the people buying tickets to see a film in 3D probably would have gone to see it if it had been strictly 2D. That, is, 3D itself is probably not luring in many new viewers. If every person buying a 3D ticket would refuse to see the film in 2D, then, yes, the figure would be 40%. I’m sure a small percentage of people are lured to see a given title only because it is in 3D. There’s no way to know how many, however, so let’s stick to the facts we do know.

The basic fact is that the money brought in by a film made in 3D only amounts to the supplement paid by the spectator beyond what he or she would have paid if the film were in 2D. Let’s assume that the supplement is $3 and that a 3D admission costs $12 and a 2D one $9. Let’s also assume for the sake of argument that everyone who saw the film in 3D for $12 would pay $9 to see the same film if it were only available in 2D. (In reality, there’s also evidence that 3D keeps some people away from a film altogether if they don’t have access to 2D screenings. I’ll assume these two groups, the 3D enthusiasts and the 2D hold-outs, cancel each other out.) Removing the $3 supplement takes away 25% of the ticket price. So what the 3D process as such really adds to the box-office total is 10% (that’s 25% of 40%). To put it another way, $9 of the $12 for the ticket is just for the film qua film, the rest is for its being in 3D.

In addition, the costs for the glasses and any extra labor they entail have to come out of that $3. I don’t know what such costs are, so I’ll leave those expenses out of the calculations.

Consider the opening weekend of Captain America, which grossed $65.7 million, 40% of which came from theaters equipped with 3D. But it’s really 10% by my reasoning, so it’s not $26.3 million that 3D generated, but $6.57 million. Assuming further that it costs about $30 million to make a film in 3D or convert it to 3D in post-production, Captain America would have to run in the U.S. market for around four weeks with no decline in attendance to break even on 3D. But most films decline on their second weekend, unless they open in more theaters or have terrific word of mouth. Even The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, which had lots of repeat business, declined 19% on its second weekend.

Of course, the popularity of 3D films is holding up better abroad than in the domestic market–so far. Still, we have to remember that only about half of the worldwide box-office receipts make their way back to the studios. That seems to imply that a film would have to gross $600 million internationally to break even on the addition of costs for 3D. ($300 million going to the studios, roughly 10% of which is paid for by 3D supplements=$30 million.) Some films do gross that much. Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, Transformers: Dark of the Moon, the final Harry Potter installment have passed that mark this year. It’s not common, though.

Naturally if a film takes in as much as 60% of its box-office from 3D screens, as Transformers: Dark of the Moon did, 15% of the costs of 3D will be paid for by the process.

How consistent is the trend?

Let’s look at the major 3D films out so far this year in terms of percentages of gross vs. percentages of theaters:

Film: Release Date (% of BO from 3D / % of locations showing 3D)

Green Hornet: January 14 (69% / 75%)

Gnomeo and Juliet: February 11 (58% / 60%)

Rio: April 15 ( 58% / 68%)

Thor: May 6 (60% / 69%)

Pirates of the Caribbean: 4: May 20 (46% / 66%)

Kung Fu Panda: 2 May 26 (45% / 69%)

Green Lantern: June 17 (45% / 71%)

Cars 2: June 24 (37% / 61%)

Transformers: Dark of the Moon: 3 July (60% / 70%)

Captain America: July 22 (40% / 68%)

Opening weekend only : Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2: July 15 (68% / 71%)

[Added July 31: The opening weekend for The Smurfs followed a similar pattern. The July 29 release made 45% of its gross from 3D engagements; 60% of its venues showed 3D. As Box Office Mojo points out, on the same weekend in 2009, G-Force made 56% of its opening-weekend gross in 3D, which showed in only 43% of theaters.]

(Granted, there is a problem with such figures. The percentage of locations showing 3D is based on theaters, not screens. Any multiplex showing 3D counts as 1, even though it may have 3 screens showing 3D and 2 showing 2D. Whether those two 2D screens would be credited to the venues showing 3D or 2D is not stated. Unfortunately, the way box-office figures are reported, there is no way to calculate by numbers of screens. We’ll do what we can with what we’ve got. In addition, venues without 3D tend to be one- or two-screen theaters in small towns. That 2D now brings in more than half the gross income for most 3D films is all the more impressive.)

Now for the list of films. There are interesting patterns here. First, the drop in 3D percentages came at about the time when the summer-movie season began, and with one exception is has proven surprisingly consistent, hovering in the 40-45% range. Second, the greater the gap between the percentage of income and the percentage of theaters, the less well 3D would presumably be performing for each release. Thus although Transformers: Dark of the Moon brought in a higher percentage of 3D income, it performed proportionately no better than, say, Rio. Third, as long as the percentage of income is less than the percentage of theaters, it should be the case that the average per theater for 2D showings should be higher than those for 3D—which is true for every film.

More theaters, fewer tickets

The decline in 3D’s contribution to film grosses has come despite the fact that the number of screens in the U.S. equipped to show 3D has gone up roughly six-fold since the beginning of 2009: from under 2,000 to over 12,000. Take a look at this graph from The Economist (derived from information supplied by BTIG Research and Screen Digest). The point where the lines cross is May, 2011:

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

Kvetching about 3D as a process and as a method of purse-gouging has declined somewhat, or at least that’s my impression. It’s not gone, though. Take a look at Mark Harris’ smart piece, “Honk If You’re Sick of 3-D!” in the June 24 Entertainment Weekly. Justin Chang’s Variety review of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows: Part 2, while generally very favorable, concludes: “D[irector of].p.[hotography] Eduardo Serra’s brooding, beautiful work gains little, however, from the underwhelming stereoscopic conversion; this is the first Potter film to be released entirely in 3D as well as 2D, and on this count, at least, one can be grateful that it will be the last.” “The “entirely in 3D” phrase refers to earlier episodes which have had a few scenes in 3D.)

There was also the controversy back in late May over whether 3D lenses, which notoriously cast dim images of 3D films, were being left on movie projectors for 2D screenings, thereby dimming the light getting to the screen for them as well. I don’t have the space to trace that discussion, but you can read about it in the original Boston Globe article, Roger Ebert’s indignant follow-up, and an expert projectionist’s assessment of the situation. Here the problems were being discussed largely in relation to 2D screenings.

But for quite some time now the larger 3D-equals-dim-images notion got wide coverage, and the topic had featured in many articles and postings critical of 3D. All that must have had some impact. In June Variety announced that for Transformers: Dark of the Moon Paramount would take “the unprecedented step of releasing a special digital print aimed at delivering almost twice the brightness of standard 3D projection.” These special prints, however, only went to about 2,000 theaters, those with RealD systems. But would prospective ticket purchasers know which cinemas had these prints? As Variety pointed out, “Exhibs may want to avoid planting the notion that some 3D screens are better than others when there’s no price distinction between the screens.” Given that it’s almost impossible these days to call a movie theater and ask a question, I doubt whether many moviegoers who attended Transformers knew which version they saw. Paramount’s move was obviously a desirable one, but it can’t account for the relatively high percentage of the film’s 3D income. (The New York Times also covered Michael Bay’s and Paramount’s efforts to promote screen brightness for the film.)

All in all, evidence seems to show that many theater owners are losing business by showing 3D films. Of Captain America’s total gross income, 40% came from the theaters showing 3D, which amounted to 68% of all venues (2511 locations out of 3715). Flip the figures, and the 32% of the theaters showing the film in 2D brought in 60% of the gross. On average, if you were an exhibitor playing the film, you made more money if you showed it in 2D. A lot more. Even not being able to charge $3 extra.

Box Office Mojo’s report on Captain America‘s first weekend confirmed that attendance was not dropping for the film as a whole, but that a greater proportion of people were opting for 2D: “While the gross difference was a sliver, Captain had eight percent greater estimated attendance than Thor, which received more bolstering from 3D (and had IMAX): Captain‘s 3D share was 40 percent at 2,511 3D locations, compared to Thor‘s 60 percent at 2,737.

Industry spokespeople are putting a good face on all this. Rob Moore, vice-chairman of Paramount, seized upon Transformers: Dark of the Moon’s 60% 3D opening-weekend share to boost the format to Variety: “‘There are so many 3D releases, audiences now are going to pick and choose which films to see in 3D,’ Moore said, before adding that the format has become a tool more for event filmmaking. ‘If the 3D is good, audiences are going to pay for it.'” But of course, most theater-goers don’t know whether the 3D is good until they have already paid for it. They go for other reasons, whether star, director, or genre. Or maybe it’s what their date or friends or family want to see. If it has those factors and it’s in 3D, it might seem worth the extra $3.

The opening weekend for Deathly Hallows might tend to confirm Moore’s claim, but the 3D share of the gross was still slightly below the percentage of 3D theaters, if not by much, and included an unusually large number of Imax locations (274)–which charge an even larger fee for 3D. Given the fans’ frenzy to see Deathly Hallows on its first weekend, they probably bought tickets for whichever screening they could, not much swayed by whether they would be seeing it in 3D or 2D.

Another point before I move on. Consider The Hangover Part II: $80 million dollars announced budget, $562.9 million worldwide gross and still in distribution. No 3D.

Anti-3D sentiment

Some people just don’t like 3D, supplement or no supplement. I went to some of the early releases to keep up with developments in the industry. It’s part of my job, after all. But after I got a sense of what it was like, I gave it up. I think the last 3D film I saw, apart from Werner Herzog’s wonderful Cave of Forgotten Dreams in February, was Avatar in December, 2009, and the one before that Up, in the summer of that year. I just saw Cars 2 the other day, 2D and on 35mm film, a treat that we must savor before release prints on film disappear over the next few years. By the way, Cave of Forgotten Dreams is the only exception to my new avoid-3D rule, and it also happens, proportionate to its budget, to be the most successful 3D film so far this year.

I’ve seen the two Pixar films made since Up only in 2D, and I don’t miss the 3D at all—despite the fact that Pixar’s films are probably the best that have been made during the latest vogue for 3D. Cars 2 naturally had quite a few shots with depth in the set design and staging. It occurred to me when I saw them that I actually might be getting a stronger sense of depth watching them in 2D than in 3D. The human mind has all sorts of ways of reading depth cues in a flat image. 3D tends to exploit only one of them, binocularity, which I suspect minimizes the others. I have no scientific evidence for that, just my own impression formed while watching the film.

I’m far from alone in avoiding 3D. The other day I participated in an online exchange on the subject. Sean Axmaker, contributor to the Parallax View website, wrote on his Facebook page that he had just seen Deathly Hallows 2 on film, in 2D and added, “I’d see “Captain America” here too, but it’s only in 3D and I just don’t see the need to see it with an extra pair of glasses on.”

The issue of studios and theaters switching entirely from 35mm release prints to digital projection would require a whole additional entry. But in late May Variety ran a long story, “Studios must revisit d-cinema,” with people from within the industry recounting dismal experience viewing both 3D and 2D films with digital projection. One 3D system cuts fully half the light from the projector. Cinematographer Roger Bailey is quoted: “It’s unbelievable that in an age when we think we have unbelievable technology, and the studios are talking about eliminating 35mm film prints in the next 18 months, that they haven’t begun to sort out the problems that have been caused by digital projection.”

The Economist ended its recent article, the one that contained the above graph, on a sour note:

Richard Gelfond, the boss of IMAX, reckons customers have become picky. “People used to see something just because it was in 3D,” he says. Now they ask how much pleasure the glasses will add. The explosive “Transformers 3” did well in 3D; perhaps the 2D version was not sufficiently headache-inducing. The key to three-dimensional projects, then, is to put out hugely popular films with extraordinary special effects. Easy.

Speaking of headaches, a small study conducted at the University of California-Berkeley seems to indicate that 3D glasses can cause eyestrain and discomfort. For those who want the full scientific text, it’s here. For a brief summary, go here. The main point is that the eyes naturally try to focus on the screen (the focal distance). The vergence point is where the imaginary lines going out from the 2 slightly separated 3D lenses come together. If it’s in front of or “behind” the screen, eyestrain can occur, since one is trying to focus on two different planes in depth simultaneously. The problem turns out to be worse the further you sit from the screen.

I myself have not noticed eyestrain or headaches caused by watching 3D movies with the current generation of glasses. I could imagine that since eyestrain is cumulative, those who watch large doses of television or spend hours at a 3D gaming console would have greater problems with the glasses.

Whether we want it or not

Business types seem to think people want 3D inserted into their lives. Note the 3D Webcam, pictured at the bottom. The accompanying text says, “The Minoru 3D Dual lens web camera is still at proof of concept stage atm but it can create stereoscopic 3D video which needs those cool blue and red 3D glasses to view.” (Note: “atm” means “at the moment,” not “go withdraw some money to buy one.”) I also ran across the 3D drawing pad pictured below left. It is available from the Perpetual Kid website, which explains: “Each page is a stereographic background for your writing or drawing. Put on these ultra cool (come on…you know you look good in them!) 3D specs and see your lines float above the page!” Why do people promoting such things seem to think that we can be convinced these glasses are cool?

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

Right now there’s a big push to sell 3D mobile phones and other handheld gadgets. On July 25, Roger Cheng posted a skeptical article on the subject of the Thrill 4G model, by LG:

But it’s unclear if consumers are ready to grab hold of it yet.

3D is the latest feature to be crammed in the increasingly Swiss Army-knife-like smartphone. Like with televisions, the feature is getting aggressive marketing support. But despite the marketing campaigns, the feature has been little more than a gimmick. And like 3D televisions, there’s been tepid interest.

“3D is just one of an onslaught of features that end up on a phone even if people don’t ask for it,” said Maribel Lopez, an analyst at Lopez Research.

Sam Biddell over on Gizmodo, did not hold back in commenting on the HTC Evo 3D phone:

The EVO 3D is the first phone to ever literally hurt my face. The 4.3-inch 3D screen’s glasses-free, of course, which means it uses the same auto-stereoscopic method as the Nintendo 3DS. Well, not the same—the 3DS is a joy to use and view, while looking at 3D stuff on the Evo felt like I was having my eyes gouged out, Oedipus-style. It gave me a headache. I wanted to look away. And for what? A 3D effect that just isn’t very good. To pull off a 3D picture of video that has any ‘pop’ whatsoever, you need to use framing so contrived as to render the whole thing pointless.

This, mind you, despite the fact that you don’t need glasses to see a 3D image on phones.

What’s next for theatrical 3d?

In my original “Has 3D already failed?” I wrote that it

depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else […] But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If for the rest of this year blockbuster films continue to bring in 40% of their gross revenues in 3D-equipped venues and those venues continue to be around 70% of the total locales, then I would think that the saturation point I mentioned has been exceeded. Some theater owners might decide that they could make more money with less hassle by showing 2D. That would drive 3D devotees to the reduced number of 3D houses, making their revenue go up. Which in turn would presumably make some of the exhibitors who had given up 3D go back to it, and the balancing act would continue until the precise saturation point is finally attained. But at this point, adding more 3D screens to a multiplex or converting a mom-and-pop theater in a small town would probably just worsen the problem. I think what I predicted is coming true, that multiplexes will reserve a small number of their screens for 3D and keep the rest flat. Maybe the studios will decide that $30 million is not a great investment.

The more important news is that digital projection will continue to spread. Some theaters have installed it already to save costs. Wanting to play 3D films (which mostly can only be shown digitally) has undoubtedly been a factor in exhibitors’ purchases of digital projectors, but it will probably become less so now. The studios, however, want to give up 35mm release prints, which cost a lot for both lab work and shipping. They’ll pressure the theaters until it finally happens.

Stifel Nicolaus analyst Ben Mogil downgraded box-office projections for the second half of the year and lowered his target for the company’s stock price to $27, from $32. His report came a week after similar predictions were made by Merriman Capital. The stock was trading at $25.33 late Monday.

“We believe that estimates for IMAX for [second half 2011] are too optimistic given that the [fourth quarter 2011] slate has three kids’ films, a genre which this year has seen considerably lower 3D share this year compared to last,” Mogil wrote.

Most, but not all, Imax movies play in 3-D, a technology that has been dropping in popularity among domestic movie audiences.

These downgrades came partly as a result of the fact that IMAX has had three straight quarters where income fell short of its own predictions.

This story was updated later the same day: “Imax Chief Executive Richard Gelfond said, ‘We have a diversified slate based on blockbuster films in 2D and 3D, for families and fanboys. We think it’s way too premature to predict how the slate will perform for the year.'”

As I read this, Gelfond is assuring investors that there are quite a few 2D films mixed in among the 3D films, so that the latter’s decline will not hurt the firm’s overall income.

On July 26, Variety ran a long story with Jeffrey Katzenberg giving an elaborate explanation of how Kung Fu Panda 2 underperformed in the U.S. because it opened the same weekend as The Hangover: Part 2. There’s no indication as to how a raunchy, R-rated film could run roughshod over a kid-oriented animated movie. All those older brothers refusing to take their younger siblings to the movies? Usually it’s called “counter-programming” and often it works.

According to Variety:

Katzenberg is also still high on 3D, at least overseas, where “the marketplace couldn’t be stronger,” he said. “Outside of North America, the performance of 3D continues to be very strong across many different films. We see continued interest in it and appeal for it and growth over these next 12 to 24 months. There’s still a pretty decent way for it to expand meaningfully internationally.”

Domestically, the exec admitted to being partly to blame for some of the extremely optimistic views of 3D’s revenue potential. At the same time, the pessimism of its longevity is also on an extreme level, he said.

For DWA [Dreamworks Animation], at least, 3D remains one of the best returns on investment for the company, after it was able to shave off the costs to produce its pics in the format.

Two years ago, DWA spent $15 million per pic to deliver a 3D version. Today, the cost is half that, Katzenberg said. The studio now has nine 3D films in production.

If executives keep offering rationalizations and suggestions that we look to the future instead of the past, maybe we can conclude that 3D is officially in a slump.

As seen on Gadgettastic.com

Capellani trionfante

Quatre-vingt-treize (1914)

Kristin here:

The early films of Albert Capellani are probably the most significant of all the discoveries of the Hundred Years Ago series.

Mariann Lewinsky

During the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was somewhat surprised at the relatively small audiences for the programs that included films by Albert Capellani. Those films formed the second half of a large Capellani retrospective that began during the 2010 festival. Last year’s program was a revelation to me, and this year’s only confirmed my sense that here is a truly major discovery from the period before World War I. No doubt the addition of a fourth venue and the appeal of the Boris Barnet and early Howard Hawks retrospectives drew some attendees away.

As I wrote in my first Capellani entry, his significance has only slowly become apparent over several of the festivals. Initially his films were few and scattered through the annual “Cento Anni Fa” seasons of movies made one hundred years earlier. (The first “Cento Anni Fa” program in 2003 was curated by Tom Gunning; those since have been curated by Mariann Lewinsky.)

My first entry was handicapped by the fact that almost none of the films was available on DVD, and few of them had ever been accessible for researchers to view in archives–Germinal being the main exception. For illustrations, I mostly resorted to online versions of a few of the films, mediocre in visual quality and covered with bugs and time read-outs. The situation has changed enormously in the intervening year. Many more films have been restored; many of the archival notes at the beginning of this year’s prints were dated 2011. Moreover, in May Pathé brought out the Coffret Albert Capellani, a four-disc set with seven of the best-preserved films of 1906, as well as L’Assomoir and three major features from 1913 and 1914. Filling in the gaps to a considerable extent is the Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur disc, from the Cineteca di Bologna, released just in time for the festival; it contains twelve films from 1905 to 1911. Between them these releases contain 23 films, plus some fragments. (The contents are more extensive than it might appear, since the three features alone add up to about seven hours.) Booklets accompanying the DVDs provide much up-to-date information on Capellani. It’s hard to think of an early filmmaker whose work has gone from such scarcity to such abundance in a single year. Once again, a driving force behind this dramatic improvement has been Mariann, working with La Fondation Jerôme-Seydoux-Pathé and the archives that provided print material.

I have taken advantage of this new availability to return to my earlier entry and add illustrations to descriptions of such important films as L’Arlésienne and L’Épouvante, which I could only summarize verbally when I first wrote it. This entry takes up where that one left off, with comments on several of the newly revealed films, or in one case, a new version.

For a list of all the Capellani films so far shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD, see the end of this entry.

An artist of the 19th Century meets a new art form

Those festival guests who missed the Capellani films missed, in my opinion, the rewriting of early film history. He is not simply another important silent filmmaker to be placed in the pantheon. Film by film, this year and last, I kept comparing what I was watching with what D. W. Griffith had made that same year. In each case, Capellani’s film seemed more sophisticated, more engaging, and more polished. Overall Capellani may not have been a better director than Griffith, but for the period of the French films, I believe it would not be exaggerating to say that he was: L’Arlésienne (1908) compared with anything Griffith did that year or L’Assomoir (1909) versus The Lonely Villa or even The Country Doctor. Capellani’s L’Épouvante (1911) was shown again this year; I had to shake my head in amazement that it was made the same year as another woman-in-danger film, The Lonedale Operator. Nothing in Griffith’s pre-war career comes close to Les Misérables or Germinal.

Both Griffith and Capellani came from the theatre, though the French director had already had a much more successful career there than had the American. Both had a strong bent toward melodrama and historical epics. But their styles developed along different lines. Undoubtedly Griffith’s pioneering work in editing sets him apart; Capellani never ventured far in that area. Capellani’s strengths were in the tableau style, with lengthy takes and intricately staged action. (For David’s thoughts on the tableau style, see here and here.) Rather, his strengths were in his elaborate staging of scenes, whether with one actor or a crowd. Perhaps because of his theatrical success, from early on Pathé must have given him generous budgets, for his settings are more opulent than Griffith’s, and he frequently went on location to the spectacular and picturesque landscapes and buildings of France. For example, he could simply take his team into old streets in Paris and create a more realistic impression of the city in the French Revolutionary era than Griffith could manage with the sets of Orphans of the Storm eight years later. (See left, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge, 1914; note how close Capellani places the camera to the wall at the left, exaggerating at once the sense of depth and of narrowness.)

There is no doubt that in the long run, Griffith’s editing-based approach won out and helped establish the norms that remain with us to this day. It has been all too easy to trace the history of cinema as, at least implicitly, a history of innovations in editing. The great directors were those who fit into that specific history. Although Griffith never entirely mastered the classical Hollywood style the way Allan Dwan or Rex Ingram or Maurice Tourneur did, the continuity editing system undoubtedly grew in part out of techniques he popularized. In an historiographic approach based on editing, those who did not contribute to its development are likely to be passed over. Capellani uses every technique but editing with great artistry, and hence his films may be easy to dismiss as theatrical or old-fashioned. Moreover, many of them are based on 19th-Century classics, especially by Zola and Dumas, even when they deal with an older period, notably the French Revolution in his last two surviving French features, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge and Quatre-Vingt-Treize.

Yes, as Mariann wrote in last year’s catalogue, “Capellani’s profile made him the target of a film historical trend–now long discredited–which criticised ‘the theatrical’ and promoted ‘the filmic.’ This is perhaps why he was so underestimated.” I am not sure that the contrast between theatrical and filmic cinema has entirely disappeared even today, but if we assume that all film techniques are equal, we can better appreciate Capellani in the context of his era.

I admit that, to a film historian or buff who learned early cinema from seeing Griffith and Chaplin and perhaps Hart and Feuillade, Capellani’s films may at first take some getting used to before their virtues become apparent. A feeling for Victorian narrative art, both written and visual, would help. At first, the acting might seem histrionic, and there are probably few, if any other directors’ films that so well preserve the stage conventions of the previous century. But for the most part, the acting in Capellani’s films is quite brilliant. The lack of editing might be a hurdle for some. Capellani also entirely avoided dialogue titles, and the expository titles are few. Characters are constantly writing and reading letters, which substitute for intertitles. It’s a convention one must simply accept, and it forces the viewer to concentrate fiercely on the actors’ faces and gestures, which carry the narrative information. For me, all this simply adds up to gripping filmmaking.

Take L’Assomoir, the earliest undeniable masterpiece from among the films so far shown at Bologna (though L’Homme aux gants blancs and L’Arlésienne come close). It is full of lengthy takes with intricate choreography. In all his films, Capellani clearly gave precise movements and business to each actor present, no matter how insignificant, and their faces, stances, and gestures, often fairly broad, make up for the almost entire lack of cut-ins. Take the scene where Gervaise and her new fiancé Copeau celebrate their engagement in an open-air café, with the proceedings interrupted at intervals by Gervaise’s former lover Lantier and the vengeful Virginie, with whom Lantier has taken up. The scene is done in a single two-minute shot, with the fluid action moving forward and back, in and out.

The ten frames below show phases of the action:

(1) Lantier in the foreground and Virginie in the middle ground watch the engagement party guests arrive. (2) Virginie speaks to Gervaise as Copeau comes forward.

(3) The guests begin to dance, with an organ-grinder coming in from the right. (4) The dancers move out left, and Copeau and Virginie begin to dance.

(5) They move out left with the organ-grinder, leaving Gervaise alone. (6) A comic friend who is continually eating comes back in to speak to Gervaise and then leaves.

(7) Lantier comes in from the right and starts bullying Gervaise. (8) Another friend comes in and drives him away out right.

(9) The dancers and organ-grinder return, with Virginie still dancing with Copeau. (10) The scene ends as Gervaise sits disconsolately while Virginie moves to Lantier and the pair watch Gervaise menacingly from the extreme right edge of the frame.

Similarly complex scenes, notably a celebration of Gervaise’s birthday, follow, culminating in a final shot that runs 6:45 minutes, out of a 35:46 minute film! (There is a pair of titles in Flemish and French that interrupt the shot early on, but the take was clearly continuous, and the titles seem likely to have been added by the exhibitor in whose collection the sole known surviving print was discovered.)

As Mariann also points out, one can find “filmic” elements in Capellani, including “the sheer photographic beauty of exterior shots, which is not to be found in the work of any of his contemporaries.” The frame at the top of this entry, made in 1914, is striking enough. (Mont St. Michel appears only in this fashion, as a tiny shape in the backgrounds of a few shots to establish that the characters have landed on the Normandy coast, but otherwise does not figure in the film.) But I suspect few would guess that the shot illustrated at the bottom was made as early as 1906.

The temptation is to go on and on about Germinal and make a long entry even longer. But Germinal has been the most familiar of Capellani’s films, and I mentioned some writings on it in my first entry. I’ll just make a few remarks about it here.

First, Capellani does a remarkably good job of capturing the naturalism of the Zola novel, as the first frame below suggests. Second, the scenes in the mine convincingly convey a sense of cramped working spaces, despite the need to shoot on sets (second frame below).

The film also makes highly effective use of the giant slag heaps behind the coal fields, placing them in the backgrounds of shots in various locales:

Clearly the resemblance of these neatly squared-off heaps to pyramids did not escape Capellani. (Compare the Red Pyramid at Dashur, above.) I think he intended this to be noticed and to be part of a motif linked to the decor of the mine owner’s study:

Like many rich men in the movies of this era, the owner is characterized as a collector of antiquities and of modern statuary with ancient motifs. (One film shown this year, I forget which, showed a rich man buying such pieces.) A case in the hallway beyond the study presumably houses his real ancient pieces, while his desk sports a small modern statue of a samurai, and the mantelpiece holds a modern Egyptianizing bust of a woman. Capellani was probably intentionally comparing the mine owner to a pharaoh and his workers to the “slaves” who built the pyramids. (This was the view of the time, though the pyramids were in fact built with paid labor.) Such a conceptual use of motifs again marks the sophistication Capellani’s films had reached by the “anna mirabilis” of 1913.

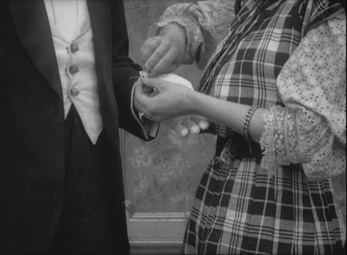

A major step forward since last year is the fact that we now have a reasonably complete print of L’Homme aux gants blancs. As it demonstrates, Capellani can cut in on those rare occasions when it’s necessary (first frame below). Here we need to see the detail of the seamstress fixing a loose button on the new gloves, not just for its own sake but because those gloves will later be lost, found by a thief, and deliberately dropped beside the body of a woman whom the thief kills. The seamstress’ identification of the repaired glove leads to the arrest of the wrong man. In the final shot (second below), the devil-may-care thief, witnessing the arrest, enjoys the irony by holding the door open for a police inspector and handing him his dropped cane. The ending is grim, since the paddy-wagon departs, leaving us to assume that the wrong man will be punished.

I can’t mention all the films shown this year, but two I particularly enjoyed were La Bohème (1911) and Le Signalement (1912), neither of which I can illustrate.

Firstly, this year Capellani’s brother Paul, whom we have seen in smaller roles in previous years, emerged as a fine actor, with perhaps his best work being as Rodolphe in La Bohème. (He played the same role opposite Alice Brady in Capellani’s American feature based on the same story, La Vie de Bohème, in 1916; there the more restrained acting style favored in the U.S. by that point makes his performance less dynamic and affecting.) The familiar tale is compressed but movingly told.

Le Signalement (“The Description”) in some ways echoes the remarkable dramatic twist of the previous year’s L’Épouvante. There a burglar ends by gaining our sympathy, and the suspense during the later part of the film centers not around the frightened heroine but around whether the terrified man will fall to his death. The heroine’s compassion makes for a moving resolution. In Le Signalement, Capellani raises the stakes. A shoemaker and his daughter (granddaughter?) Jeanette, played by the excellent child actor Maria Fromet, live in a French village. The police circulate a flyer describing a child murderer who has escaped from a nearby insane asylum. While delivering some boots, the cobbler is lured to linger in a tavern, and the murderer comes to the house. In characteristic fashion, Capellani lets most of the length of the killer’s time in the house play out in a single take into depth; the camera faces diagonally across the room toward the open door, the only place where help might appear.

When the escapee arrives, Jeannette innocently invites him in and offers him some food, including a dangerous-looking knife to cut a piece of pie. Tempted to kill and yet overwhelmed by the child’s kindness, the man sits and eats. Capellani ups the ante when Jeannette lifts a crying baby, whose presence we had not previously noticed, out of a basket to comfort it, even handing it to the man to rock. During all this we are left in suspense as to whether he will give in to his murderous obsession or resist it. At last the pair hear the police outside, and Jeannette realizes that her visitor is the killer–yet she helps him to escape out the window. Again we are torn, not wanting the child’s generous gesture to be thwarted and yet not wanting a child murderer to run loose! The plot solves the dilemma in a neat and dramatic fashion. Overall, like L’Homme aux gants blanc and L’Épouvante, Le Signalement packs conflicting emotions into a single reel.

Such density of narration is one characteristic of Capellani’s work. As Mariann wrote in the program last year: “Capellani’s speciality as a director is the broad scope of his narratives, connecting different locations and characters, which invests even short films with grandeur and space, to such an extent that the film lengths, given in either metres or minutes, often seem unbelievable. What? Can L’Épouvante really only be 11 minutes long? And Pauvre mère and Mortelle Idylle only 6 minutes each?”

Two final French features

Apparently Capellani made eight films in 1914, but as far as I know, only two survive. Both happen to deal with the French Revolution, and both are based on 19th-Century novels: Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (Dumas) and Quatre-Vingt-Treize (Hugo).

Last year I suggested that Le Chevalier might be a bit of a let-down after the heights of Les Misérables and Germinal. But it would be hard to match Germinal, and I have to admit that upon seeing Le Chevalier again on DVD, it kind of grew on me. The main problem, I think, is that Capellani doesn’t take much trouble to give the characters traits and make them sympathetic. They seem more like game pieces in service to the plot. But as always the staging and acting are marvelous, and both locations and sets, as I suggested above, give a vivid sense of revolutionary Paris.

Oddly, though, for the first time there are signs that Capellani is being influenced by cinematic trends of the day and is trying to expand his style in a somewhat tentative way. Clearly, like so many filmmakers, he has seen Cabiria and been impressed by its lumbering tracking shots. The tribunal near the end where the young lovers, Maurice and Geneviève, are condemned uses such a tracking movement well, pulling out from the lovers and the court to include the crowd that welcomes the death sentences:

In a few scenes Capellani also explores offscreen space in a way that I haven’t seen in his other films. Most dramatically, when Maurice sneaks up to the house where he hopes to see Geneviève, he appears small in the distance, disappears out the bottom of the high-angle framing, and suddenly reappears very close in the foreground, having somehow climbed up to a window:

In one scene Capellani even cuts in for a closer view and a different angle during a letter-writing scene. It’s a bit clumsy, with a mismatch on the man’s position–though not one that is worse than many attempted matches in European cinema of the 1910s:

The cut-in isn’t really necessary, though, and one would expect Capellani not to use it. This is one of the few moments in all the films shown where briefly Capellani seems truly old-fashioned, catching up with a technique that had already been in use for a few years. Here I wish he had stuck to his accustomed long shots, for it’s a sign of things to come. The next year Capellani would be working in the U.S. and making a smooth transition into continuity editing.

Capellani’s last film in France was Quatre-Vingt-Treize. With the outbreak of World War I, the subject matter, French fighting against French during the Revolution, was considered too provocative in a fervently patriotic context, and the film was banned. Capellani did not finish it but went immediately to the U.S. After the war, it was completed by his fellow theatre/film director André Antoine and finally released in 1921. There is no sign of any of the footage being by a different hand or done at a later time. It appears that Antoine simply edited the footage, perhaps to a script or shot list from the director, since the result on the screen is pure Capellani. It eschews the mild experiments of Le Chevalier and returns to a concentration on acting and a wonderful use of locations. At one point, in a single take, a troupe of Revolutionary soldiers marches past in a woodland setting. After they exit, there is a brief pause, and a man rises up from behind the foreground rocks in the path, signaling. Suddenly counter-revolutionary soldiers pop up all over the frame from the undergrowth and follow their foes stealthily in a seemingly unending stream:

In this film the characters are assigned more traits than in Le Chevalier, and the result, even at 165 minutes, is a rattling good tale.

(I mentioned that Capellani avoided dialogue intertitles. This films has some, but it may be that Antoine added those on his own.)

Despite dealing with the same historical period, the two films say nothing about Capellani’s politics, since in Quatre-Vingt-Treize the sympathies are clearly with the Revolutionaries, and in Le Chevalier, they lie with the group, including the title character, who are plotting to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison.

The American period

Given Capellani’s expertise in and long use of the tableau style of filmmaking, it is remarkable how easily he adapted to Hollywood. Only a few of his films from the early years in Hollywood survive, and His La Vie de Bohème (1916), a pleasant, well-made film, is not nearly as lively and absorbing as the French version, La Bohème (1912). I enjoyed the other features shown, Camille (1915, starring Clara Kimball Young) and The Virtuous Model (1919, starring Dolores Cassinelli), but I couldn’t help missing the French Capellani. It is hard to imagine how his career would have developed had he stayed in France. Perhaps, like Victor Sjöström and Ernst Lubitsch, he could have waited until after the war to move smoothly from the tableau style to adopt continuity editing. Perhaps, like them, he could have remained one of the top filmmakers of the silent period. (He returned from Hollywood to France after directing the 1922 Marion Davies vehicle The Young Diana. He did not direct again and died in 1931.) Good though the Hollywood features are, however, for me they inspire none of the sense of discovery and excitement that the films of the 1908 to 1914 period do.

Wishful thinking

By the 2011 festival, most of the known Capellani films have been restored. Some have improved before our eyes. In 2008 and again in 2010, the older restoration of L’homme aux gants blancs (1908) was shown. The newer, more complete restoration combines images derived from a 35mm print and a 28 mm one. A new restoration of Germinal with toning based on original color indications was shown this year.

There were also some fragments, which were saved for the seventh and final program in the series, “Borders and Blind Dates (A Workshop).” There is a version of Le Belle et la bête, for example, that is badly deteriorated, even within most of the footage retained by the restorers. What little remains suggests that the film must have been quite charming; the fragment is included among the extras on the Cineteca di Bologna DVD. There were also some films that were considered as possible Capellanis. According to the booklet accompanying the same DVD, Capellani is thought to have made anywhere from 70 to 80 films from 1905 to 1912. The number is uncertain, due to problems of attribution. Of these, about half survive, less than a third of them from the 1910-1912 period.

La loi du pardon, a 1906 melodrama of the type Capellani frequently made, is listed in the festival catalogue as “Ferdinand Zecca? Albert Capellani?” It could be Capellani, but to me most of his films of the 1906-07 years, though excellent, are not distinctive enough to be attributed to him without any documentation. Manon Lescaut (1912 or 1914; it is listed as both in the program on pages 128 and 129) was more tantalizing. An adaptation from a classic French novel, made by Pathe’s prestigious S.C.A.G.L. unit, would seem exactly Capellani’s sort of project. The first scene, set in an open-air café, seemed plausible as his work, but the rest of the film has little or nothing of his style about it. Instead there is a lack of long-held, intricately staged shots, one completely unnecessary cut-in, and too many old-fashioned painted sets. Compared to the location work in Germinal or just about any of the big films from the immediate pre-war years, these looked crude. Plus, as Caspar Tyberg pointed out to me, the action was staged more quickly than one would expect from Capellani, who often lets situations develop gradually, with many details in the gestures and facial expressions. There are some of his films in archives but apparently as yet unrestored. (According to the booklet accompanying the Coffret Albert Capellani, the Cinémathèque Française has a negative of a 1909 version of Manon Lescaut.) Otherwise I fear we must count on future discoveries in the archives for more Capellani films. Surely some will be forthcoming, now that archivists are aware of the importance of this newly revealed master. “Cento Anni Fa” will move on into 1912, 1913, and 1914, and perhaps the Capellani retrospective will resurface occasionally.

With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work. If you live outside Europe and don’t already have a multi-region DVD player, this might be the time to invest in one. It would be worth it just to see these new DVDs.

Capellani films shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD

Symbols used in the list:

* A film on the Coffret Albert Capellani, (La Cinémathèque Française, La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé), Pathé, two four discs with booklet, Region 2 Pal. 36-page booklet in French. There is a bare-bones filmography, with titles and dates, on page 35, but this no doubt will be revised as research continues.

** A film on Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur 1905-1911 (La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, the Cineteca Bologna) Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 disc with booklet, Region 2 Pal. Intertitles in various languages; optional subtitles in Italian, French, and English. 55-page booklet in Italian, French, and English.

+ The titles I would most like to see on a future DVD!

In last year’s entry, I expressed the hope that some films from previous years could be repeated. Whether or not that hope influenced the programming, some were.

[Added July 19: Mariann tells me that she is now convinced that La Loi du pardon is genuinely a Capellani film. I find that quite plausible.]

2005

*Le Chemineau (1905)

2006

**La Fille du sonneur (1906)

2007

*Les Deux soeurs (1907)

*Le Pied de mouton (1907)

**Amour d’esclave (1907)

2008

Don Juan (1908)

La Vestale (1908)

*Mortelle idylle (1908)

Corso tragique (1908)

Samson (1908)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908)

Marie Stuart (1908)

2009

*L’Assomoir (1909)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909)

2010

Dans l’Hellade (1909)

**Le Pain des petits oiseaux (1911)

*La Fille du sonneur (1906) (Repeated from 2006)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1911)

+Les Miserables (1912)

**Le Chemineau (1905) (Repeated from 2005)

*La Femme du lutteur (1906)

**L’Arlésienne (1908)

Eternal amour (1914)

**L’homme au gants blancs (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

**L’Épouvante (1911)

*Pauvre mère (1906)

**L’Intrigante (1910-11)

La Mariée du château maudit (1910)

**Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (1907)

Samson (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

*Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914)

*Drame passionel (1906)

**Le Pied de mouton (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909) (Repeated from 2009)

La Fin de Robespierre (1912)

+La Glu (1913)

The Red Lantern (USA, 1919)

*Mortelle idylle (1906)

+L’Évade des Tuileries (1910)

2011

La Belle au bois dormant (1908)

Le Courrier de Lyon ou l’attaque de la malle poste (1911)

+La Bohème (1912)

La Vie de Bohème (USA, 1916)

*Quatre-vingt-treize (1914, released 1921)

**[Amour d’esclave (1907) Not shown for lack of time]

+Le Signalement (1912)

*L’Âge du Coeur (1906)

**Les Deux soeur (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

Camille (USA, 1915)

*Germinal (1913)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908, more complete restoration)

Le Visiteur (1911)

Marie Stuart (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

Le Luthier de Crémone (1909)

The Feast of Life (USA, 1916)

**La Belle et la bête (1908, fragment) In “Extras” on DVD

Foulard magique (1908, fragment)

Béatrix Cenci (1909, incomplete)

**La Loi du pardon (1909) By Capellani or Ferdinand Zecca

La Legend de Polichinelle (1907)

[August 13, 2012: Roland-François Lack has recently added a post on Capellani on his website, The Cine-Tourist. He gives an extraordinarily detailed run-down of the Parisian (and Vincennes) locales used by Capellani (such as the one below), with many frames from the films and both current and vintage photos of the places, as well as a few maps and some engravings and other graphics. Well worth a look!]

La Fille du sonneur (1906)

Cognitive scientists 1, screenplay gurus 0

Kristin here:

The annual meeting of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image is currently taking place at Elte University in Budapest. It runs from June 8 to 11. It must have started off very well. Barbara Flueckiger posted this comment on the opening keynote address on Facebook: “Just attended an absolutely fascinating and inspiring talk by Talma Hendler, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience: ‘Brain Shows Where the Drama Is. A Call for an Empirical Neurocinematic Agenda.'”

Last week David posted a new web essay on “common-sense film theory” as a way of participating from afar in the work going on in Budapest. Now it’s my turn to post a SCSMI-related item.

The mirage of the second-act desert

Twelve years ago I published Storytelling in the New Hollywood (Harvard University Press). It included a claim that most classical Hollywood feature films have four acts, lasting roughly 25-30 minutes each, adding up to a film of from 100 minutes to two hours. This claim ran counter to the old notion, popularized by Syd (Screenplay) Field, that Hollywood movies (and, according to Field, all feature narrative films) have three acts of 30, 60, and 30 minutes respectively.

My book analyses ten films in detail, dividing them into their four parts: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax (usually including an epilogue). I also have an appendix listing ninety additional films that I timed by large-scale part, ten for each decade from the 1910s to the 1990s. My conclusion was that most of these films stuck to the four-part structure with each part within five minutes either way of lasting a half-hour. Some of the exceptions were actual three-act films (e.g., Adam’s Rib) and others were longer films. Amadeus, one of my ten main examples, is 160 minutes long and has five large-scale parts. (“Large-scale part” was the rather cumbersome term I employed in the book, trying to avoid the misleading word “act.” I have to admit though, that there’s little chance of people discontinuing “act” and switching to “large-scale part.”)

I also defined the “turning point” that Field says divides acts more concretely than he does, specifying that it usually results from moments when the main characters formulate or modify the goals that drive the narrative forward. (I expand upon the relationship of goal shifts and turning points in a previous entry.)

Unlike Field and other screenwriting “gurus,” I allow for exceptions to my four-part schema. The Pink Panther doesn’t have a turning point until over 52 minutes in; the lengthy early part of the film consists of a bedroom-farce situation of male sexual frustration that makes absolutely no progress toward the putative subject of the film, the theft of a valuable jewel. As far as I can tell, It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World has no turning points at all. I remember thinking it was quite funny when I saw it as a child.

Some screenwriters have read the book, and some who teach screenwriting courses assign it as a textbook. At least it’s still in print, which is something to be grateful for at my age.

Since the book was published, it certainly hasn’t knocked out the conventional view that films have three acts. Not infrequently I read a review in Variety or another specialist journal that refers to the last quarter of the film as the “third act.” The idea that films fall into chunks lasting 30 minutes, 60 minutes, and 30 minutes, no matter how counterintuitive or inaccurate, is too entrenched to be dislodged, apparently.

Still, I have the consolation that I’m apparently right. Other people have tried out my claim and found it to work. Creative Screenwriting gave a very kind review to my book (in its March/April 2002 edition, not online). D. K. Holm, the reviewer, was inspired to test out my system on the next three films he saw in theaters. He declared that it worked as predicted for The Shipping News, In the Bedroom, and even Ali, a five-act film. (My claim is that longer films don’t stretch their four acts. They add more, roughly 30 minutes long, for every half hour beyond the standard two-hour feature. Roughly half an hour apparently seems to create a pleasing balance as far as Hollywood practitioners are concerned—whether they’re aware of it or not.)

Real scientists at work

Now James E. Cutting, whom we enjoyed meeting and talking with at last year’s SCSMI conference (David devoted part of his report on the conference to James’s work), has collaborated with two of his graduate students, Kaitlin L. Brunick and Jordan E. DeLong, on a quantitative study related to Storytelling. They set out to test the whether the four large-scale parts of a classical film are reflected on the stylistic level. Specifically, do shot lengths and the use of non-cut shot transitions (fades, dissolves, and the like) vary in a patterned way across or among the parts?

It’s exciting to see cognitive scientists study claims that I’ve made on the basis of close film analysis. David has had his claims about staging and attention in There Will Be Blood confirmed by Tim Smith’s eye-tracking research on the same sequence. Now the results of Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work relating to the four-part structure have been published in Projections (Vol. 5, issue 1, Summer 2011), subscriptions of which are included in SCSMI membership. Luckily I didn’t know this article was on the way, or I might have been in some suspense to find out whether my model worked. (This and other articles on film are also available online, linked from this page that lists the work on film published by James and his colleagues.)

As the authors’ starting point, they accepted my four-part structure. Or as they put it:

We find Thompson’s argument persuasive and her data remarkably clean. Nonetheless, the division into acts is built on a detailed analysis of the narrative, and we work from the physical properties of film. Many observers might agree on act divisions, but these divisions would not necessarily be reflected in any physical measure of a film’s shots and transitions. Thus, without prejudice as to what we might find, we sought data in shot lengths and in shot transitions that might corroborate Thompson’s analysis. (p. 4)

The team used 150 films they had previously studied in their work on editing patterns and their possible correlations to human attention. Of these, some were eliminated because they were too long, so that the statistical work could concentrate on films with four parts. I cannot claim to be able to follow all the statistical manipulations the data from these films were put through—though I can tell from the information in the footnotes that the degree of probability for some of their results indicated an amazingly small chance of error.

The figure at the top is a “scatter plot” of shot lengths for 143 Hollywood films from the period 1935 to 2005. These figures have been statistically adjusted in ways that allow the films to be compared despite their differing lengths. (I have no idea how this sort of thing is done. You’ll have to see the explanation in the article.)

One striking revelation of this chart is that the lengthiest shots in the films occur at the beginning, end, and at the one-quarter, two-quarter, and three-quarter points. Moreover, the “scallop” pattern of rising and falling average shot lengths shows a “tendency toward intensification of films near the middles of acts, where shot lengths become slightly shorter.” The ASLs were found to be as much as 1.1 seconds shorter than in the early and later portions of the acts.

Luckily I was right about the four parts. But beyond that the authors came up with results supporting my claims about the functions of the plot’s third part, the Development. Here’s how.

As part of the study, the authors tackled the question of where non-cut shot changes fall in relation to the quarters of films. Non-cut changes are fades, dissolves, and the like. It turns out, not surprisingly, that quite a few of them come early on, since the exposition may move among time and places setting up the basic premises of the narrative. But the rest tend to come in the third quarter, the Development. That makes sense to me. By my definition, the Development is essentially the stretch of action where most of the major premises, goals, and obstacles have been established. Before the climax can begin, the protagonist usually struggles against obstacles, usually provided by the antagonist. Often relatively little happens in the Development to forward the action, at least in comparison with the other three parts. At the Development’s end, some vital last premise is introduced that allows the action to move into the climax portion, where the plot moves forward relatively quickly and no more major premises are introduced.

The Development might contain extra fades and dissolves for two reasons. First, a surprising number of films have a montage sequence shortly after the middle turning point. The one depicting Michael Dorsey’s rise to fame as Dorothy Michaels in Tootsie is one such. Second, since the Development often is the section where time passes until the point where the climax can begin, one would expect fades or dissolves to cover temporal gaps. I’d have to go back and watch a bunch of films to confirm those hunches, but they seem logical.

My main purpose in writing Storytelling in the New Hollywood was to show that the principles of classical narrative construction formulated in the 1910s and used throughout the studio era are still operative today. Despite film reviewers’ complaints that action and special effects have come to substitute for story appeal in modern mainstream films, the kinds of films they find so shapeless do usually stick to the same four-part structure, contain goals and conflict and the rest of the principles that have been in effect for decades. Cutting, Brunick, and DeLong’s work bolsters this claim about classical narrative’s stability over time. They find that “there are no obvious differences in these patterns for films of different eras.” (p. 8.)

This issue of Projections has other articles applying a cognitive-science approach, and with luck future issues may contain some of the papers we have been unable to attend at this year’s conference.

James, Kaitlin, and Bradford have set up an online overview of their research in progress, “Shot Structure and Visual Activity: The Evolution of Hollywood Film.” The graphics and type are quite small, but right-click on the page and click “Marquee Zoom,” which brings up the little magnifying glass that allows you to enlarge it multiple times.

For online applications of the idea of four-part structure, see David’s essay on Mission: Impossible III and his blog entry on Source Code.

Jordan DeLong, Kaitlin Brunick, and James Cutting at annual convention of SCSMI, Roanoke 2011.

Graphic content ahead

Kristin here:

Recently I received the June issue of Empire magazine. After the shock of realizing that, Ack! It really is almost June, I turned to the letters to the editor. I received an even worse shock when I read this one:

I recently discussed 2001: A Space Odyssey with my Film Studies teacher (I’m an A-level student), and mentioned (what the back of the DVD case says): “One of the most mind-blowing jump cuts ever conceived.” He told me the bone to satellite scene is actually a match cut. I then read issue 262 of Empire, and was very happy to see a Stanley Kubrick special. I noticed you also called it a “stunning jump cut”. After being told what a jump cut and what a match cut is and seeing a few examples (the jump cut at the start of Don’t Look Now, and then the match cut in 2001: A Space Odyssey), I am now confused as to why the DVD and Empire would call it a jump cut when it is a match cut.

Robby Burke, via email

It is a match cut. The offending writer has been put into a small room with only Eisenstein films for company. The moral of this story is always listen to your teachers, kids. And good luck to Owen Robinson on your Kubrick Film Studies unit. This is turning into hospital radio.

No wonder Mr. Burke is confused. His teacher and Empire both gave him answers that I would consider wrong, or at best imprecise to the point of vagueness. This rather surprised me. I enjoy reading Empire, which has somehow managed to keep itself fat and glossy when magazines like Entertainment Weekly have shrunk to the size of brochures. It even has occasional useful articles, like its retrospective section on Back to the Future in the April, 2010 issue. (As far as I can tell, this section has never made its way to the Empire website.)

The term “match cut” is, out of context, virtually meaningless. There are different kinds of match cuts, and not specifying which type one is referring to will leave Mr. Burke and the rest of us clueless as to what the teacher and the unnamed staff member for Empire mean.

Thinking I was missing something about the term “match cut,” I looked it up on Wikipedia and discovered that the teacher and the Empire staff member might have gotten their misinformation from the entry on that phrase. Its definition of a “match cut” is:

A match cut, also called a graphic match, is a cut in film editing between either two different objects, two different spaces, or two different compositions in which an object in the two shots graphically match, often helping to establish a strong continuity of action and linking the two shots metaphorically.

While the Empire use of “match cut” was only vague, this definition is simply inaccurate. The author goes on to say:

Match cuts form the basis for continuity editing, such as the ubiquitous use of match on action. Continuity editing smoothes over the inherent discontinuity of shot changes to establish a logical coherence between shots. Even within continuity editing, though, the match cut is a contrast both with cross-cutting between actions in two different locations that are occurring simultaneously, and with parallel editing, which draws parallels or contrasts between two different time-space locations.

I’ll agree that continuity editing is designed to smooth over the potentially disruptive quality of cuts. Matching anything within a scene is definitely different from cutting from an action in one place to a different action in a different place. But graphic matches are neither synonymous with “match cuts” nor the basis for continuity editing.

I also discovered that the “Further Reading” list at the bottom included two items, one of which was Film Art: An Introduction. One of those good news/bad news situations. The good news is, if you read the book, you will find out what graphic matches, and matches in general, really are. The bad news is, if you don’t, you might blame us for the contents of the Wikipedia entry.

A little detour into history

Most people don’t realize this, but David and I invented the term “graphic match.” As we recall, this happened in 1975. David was teaching a course that involved screening Yasujiro Ozu’s second color film, Ohayu (1959), a wonderful comedy about television, farting, and small talk. We had never seen the film before and were watching a 16mm print of it.

When the two shots below passed before our eyes, we both gasped and lunged for the projector. We ran the film back and watched the cut again. There was no doubt that Ozu had deliberately placed a bright red sweater in the upper left quadrant of the frame in one shot and a bright red lamp in the same basic position in the next shot. We didn’t know what to call this technique, so we dubbed it a “graphic match.” Two years later, when we started writing Film Art: An Introduction, we included the term as one technique of film editing and used Ozu’s match on red as one example. By now “graphic match” has been picked up to the point where we occasionally see it used in print.

If people, however, are tossing that term and “match cut” around so inaccurately–and even equating the two–then some definitions and examples seem in order.

Matcharama

“Match” as applied to editing simply means that some element is carried over from one shot to the next. That doesn’t necessarily mean that this element creates a sense of continuity.

In general, “continuity” means that a coherent space and time are continuing over the cut, so that the spectator’s understanding of a story isn’t disturbed by a sense that bits of time have been left out or that characters have changed positions at the cut. Most people watching a mainstream narrative film probably aren’t even aware of the editing, especially in conventional conversation scenes.

More specifically, “continuity” means a set of guidelines or loose “rules” that American filmmakers devised, mostly during the 1910s, to allow them to help create that clarity of narrative action in time and space. Within a scene, the most basic of these is the 180-degree rule or “axis of action,” the invisible line that runs through the scene perpendicular to the camera. If the camera stays on one side of that line, characters will stay in a consistent spatial relation to each other. Character A will be on the left in every shot, Character B on the right—unless one of them walks to a different part of the setting. In other words, the axis creates consistent screen direction.

The most basic kinds of matches are on appearance, position, action, and eyelines. Everyone knows that if a character is wearing a blue hat, showing her wearing a red one after the cut is a continuity error. Her appearance has not been matched. The same is true if she is resting her cheek on her hand in one shot, but has both hands flat on the table after the cut. If she is walking in one shot, she should not be running or standing still in the next. Even if the shots are made with a single camera and the actress repeats her actions, her position and movement should ideally be repeated so precisely that her action appears continuous. That’s a match on action, one of the most common continuity devices.

Smooth matches on action are difficult, especially if, as often happened in classic studio filmmaking, the two shots are made hours or even days apart. Even a supreme technician like Hitchcock can err. Here is a flagrantly mismatched passage from Suspicion. In the long shot, Johnnie (Cary Grant) reaches for the teapot with his left hand and starts to pour.

But then Hitchcock cuts in axially, the teapot is back where it was, and Johnnie once more reaches for it. By the time he’s pouring now, Lina has turned to watch him.

Editors traditionally like an overlap of 2-4 frames when they’re matching action on cuts, but this is a much longer overlap, something on the order of four seconds. Why we don’t usually notice such things is a source of considerable discussion in film circles.

The eyeline match is also very common. If a character looks at something offscreen, a cut shows us something in a different space, and we tend to assume that the character is looking at what we now see. Screen direction is important here, since if the character looks off right, when the next shot appears, we assume he is now offscreen left.

Not all continuity devices involve matches of these kinds. Crosscutting and flashbacks may move the action away from the space and even the time of a scene, but there are other cues that help us keep track of the ways in which these new spaces relate to the storyline.

None of this requires what we would consider a graphic match. Of course, if we see the same characters in the same setting from shot to shot, there will be an overall graphic consistency. They’re wearing the same costumes, and the background colors probably won’t shift greatly. But precisely because of that general consistency, we probably won’t notice the graphic qualities of the scene as being that important as elements of the editing. We’re busy following the story.

Graphic matches precise enough to be noticed as such tend to jolt us a little out of our smooth concentration on the story action. They are not the basic of continuity, as the Wikipedia definition claims. On the contrary, they often appear in films outside the continuity tradition. Abstract films often play on the graphic similarities (matches) or contrasts (mismatches) among shapes from shot to shot. Such abstract play is, in effect, their subject, and we pay attention to the pictorial flow as we would pay attention to story in a conventional narrative film.

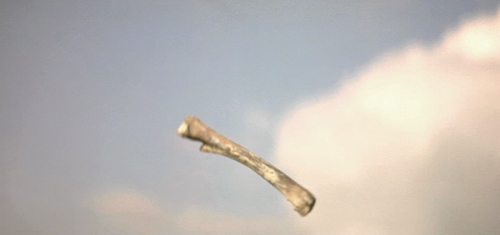

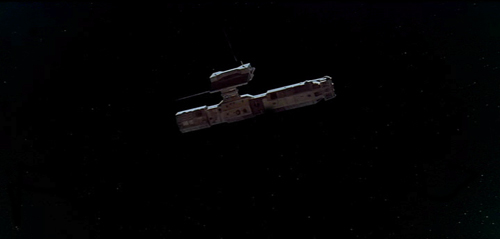

When close graphic matches or jolting graphic contrasts appear in narrative films, they may or may not play a narrative role. The famous bone/spaceship cut in 2001 is a graphic match. It’s not a match on action, since two different objects in completely different times and places are shown. It’s not a jump cut for the same reasons.

Here the graphic match is not really very close. The sky is bright and blue behind the bone, while it is dark behind the spaceship. Similarly, the bone is light in color, while the spaceship is initially dark, though it does brighten slightly as it moves. The only graphic element matched is the general shape and motion of the two objects.

The function, I assume, is to jolt the audience with the dramatic transition across millions of years and from earth into space. Thus here the graphic match has a narrative function, though it does not create the smooth movement from one scene to another that classical films tend to have. It’s more like what is sometimes called a “shock cut,” one which startles the viewer. The cut to the screeching cockatoo in Citizen Kane is one of the most famous examples, though it primarily involves sound and a strong graphic contrast.

A transition somewhat similar to the one in 2001 occurs early in Aliens, an example which we use in recent editions of Film Art. A dissolve moves from a close-up of Ripley’s sleeping face to a view of part of the earth seen from space. Again there is a passage through time and space, though the interval is presumably only a few months. Here the graphic match is much closer than in the 2001 transition, with the colors as well as the shapes being kept fairly consistent. This graphic similarity and the dissolve that emphasizes it ease us from one scene to another rather than jolting and surprising us.

In the hands of an experimental filmmaker or of an unconventional director like Ozu, who avoids obeying Hollywood’s continuity guidelines, graphic matches don’t necessarily play a narrative role. They are included as an extra layer of engagement for the viewer. We don’t, or at least shouldn’t, expect to be able to interpret them. I would contend that the link between the red sweater and the red lampshade is there for pure pleasure. You can come up with an interpretation of the graphic match if you try hard enough—but if you do, please don’t tell me about it. I suspect it would interfere with my enjoyment of that scene when I next watch Ohayu.

I don’t think the cut serves even so modest a function as establishing space at the beginning of a scene. Here’s the shot that actually begins the scene and leads to the sweater and lampshade shots:

And here’s the one that follows the lampshade shot:

The woman is a minor character. She and her husband live in the suburban housing complex where the much of the action is set. They are more modern in their habits than their neighbors, wearing western clothes rather than kimonos and owning the only TV in the complex. They function primarily to introduce the two young boys in the central family of the story to TV, since they hospitably let the local kids visit them to watch it. The scene following the graphic match shows the wife packing to move. Their absence will precipitate a crisis when the boys demand that their parents buy them a television. The strife among the family members forms the basis for much of the rest of the action.

So the packing scene is important. Yet Ozu uses two shots that he wouldn’t need, thus delaying the scene’s beginning. The extreme long shot of the housing complex doesn’t tell us which house will form the setting for the upcoming scene. The red sweater is in the distance, but barely visible. We certainly wouldn’t notice it or get any clues about the narrative from it. Yet Ozu cuts to a closer view of the sweater and a towel. The houses in the background are all identical, and we don’t know which one belongs to which characters or which we will enter in the next shot.

The first interior view would be a logical establishing shot for the scene. The modern furnishings and especially the television box let us know where we are, and the boxes might hint that the inhabitants are packing to leave. So we are not surprised when we see the modern wife in the subsequent shot. But Ozu puts in the other two as part of his typical series of transitional shots that show the spaces between locales where action occurs.

The graphic match, I would suggest, is simply part of Ozu’s distinctive style. It’s playful and fits in with the general graphic beauty of his films, which includes bright splashes of color, careful compositions using the lines of the sets, and precise placements of props.

Returning to the Wikipedia entry for “match cut,” there is a section that mentions several examples, including the one that inspired Mr. Burke’s letter:

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey contains a famous example of a match cut. After an ape discovers the use of bones as a tool and a weapon, there is a match cut to a spacecraft or satellite in orbit. The match cut helps draw a connection between the two objects as exemplars of primitive and advanced tools respectively.